Steve Lipin didn’t fit the profile of a transformative media figure when he took over the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) beat for the Wall Street Journal in 1995. His look was studious and his manner remarkably affable and low key, given the stress of his new job. His rise had not been particularly meteoric. He had started in 1985 at the bottom of the business-news food chain, financial newsletters, progressed to Institutional Investor, a magazine for pension-fund managers, and then American Banker, another trade. In 1991, he followed his boss to the Wall Street Journal to cover banking. After four years of solid, unspectacular work, he moved to M&A, a beat that was moribund at the time.

Then the scoops started to come. “Kemper Agrees to Be Acquired by Group Headed by Zurich Insurance for $2 Billion,” which ran April 11, 1995, reported that the financial-services firm was ending a tumultuous year in which it had rejected a hostile offer from General Electric and had seen a friendly deal fall apart twice. The story was based on information from “people familiar with the transaction,” a form of attribution vague enough to encompass just about anyone involved in the deal—investment bankers, lawyers, company executives, public-relations specialists. The scoops got bigger and more frequent: “First Union Agrees to Buy First Fidelity for $5.5 Billion—Swap Valued at $65 a Share” (June 19, 1995); “Kimberly-Clark to Acquire Scott Paper in Stock Deal Valued at About $6.8 Billion” (July 17, 1995); “Upjohn and Pharmacia Sign $6 Billion Merger” (August 21, 1995). Lipin’s scoops ranged across industries: banking, consumer products, pharmaceuticals: “Boeing and McDonnell Douglas Are Holding Merger Negotiations—Commercial, Military Aircraft Powerhouse Could Shake Industry” (November 16, 1995). Week in, week out, Lipin seemed to get just about every industry-transforming blockbuster.

A handful of major scoops over the course of an M&A reporter’s career is considered a great success. Lipin had, by my count, at least seventy from 1995 through 2001, and the total value of the mergers he reported on was more than half a trillion dollars. He was published on prominent pages of the Journal more than five hundred times in five years, which could be a record. Those who traded on Lipin’s information early enough stood to make serious money. The WorldCom bid alone added $8 billion to MCI’s value in a single day. Most of the time, the names of the companies in Lipin’s scoops had never been linked, let alone reported as combining. The stories often announced talks in progress, amplifying a sense of immediacy: this was news that hadn’t even happened yet. They often said the deals “could be announced as early as today.”

(A word of disclosure: Lipin was a colleague of mine at the Journal and a funder of CJR’s business desk, “The Audit,” which I ran, in 2009 and 2010, before I began this book. He became a funder of CJR and member of its board of overseers after I had begun.)

Inside newsrooms and in the markets, major M&A scoops have an electrifying effect. Mergers represent big capital-allocation decisions affecting thousands of jobs and billions of investor dollars. And while M&A is routine on Wall Street, for most companies it is a one-time roll of the dice because of the amount of money involved. An acquisition taken is a dozen alternatives foregone. Big deals are also benchmarks—important pricing moments that help determine values and, in fact, create new realities. What was unthinkable one day—AOL/Time Warner, for instance—is reality the next. For a news organization, deal scoops create an aura of omniscience, a sense that it is plugged into Wall Street.

But Lipin’s never-to-be-equaled run was part of a much larger wave, a transformation of the American economy and, with it, business news. The financial sector rose, the number of M&A deals exploded, and, more important for our purposes, the middle class stampeded into the stock market to an extent never before seen in American history. All eyes, it seemed, turned to the stock market—Wall Street—and business news ballooned with new outlets and reconfigured itself to meet this new interest. The push-me-pull-you struggle between access and accountability was about to lurch again.

Many people over the years have tried to puzzle through the question of why the news looks the way it does. In The Brass Check, a 1919 exposé of American newspapers, muckraker Upton Sinclair argued that his fellow journalists were little more than servants of elites, plying their craft to serve the political and financial interests of their employers, newspaper owners. The “brass check” referred to the token purchased by a brothel patron who would then give it to the prostitute of his choice—the journalist, naturally, being the prostitute. The propaganda model of Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky can be seen as a variation of the brass-check theory, with an added caveat that professionals within journalism can occasionally escape the boundaries drawn by owners. But those successes, the theory goes, only serve to disguise the fact the boundaries exist in the first place. Herbert Gans, meanwhile, argues that “the news” is a culture unto itself. Rather than being a compliant supporter of elites, or the “Establishment,” journalism culture views nation and society through its own set of values and with its own conception of the good social order. Reflecting a less polarized time, Gans asserted journalism could not be categorized as either conservative or liberal but rather reformist in tendency.1

The theories have merit. The trouble with them is that they’re static, and news culture isn’t. Rather, it changes over time, reflecting public tastes, social trends, the political climate, and internal battles for newsroom primacy. In my view, the dynamism of twentieth-century business journalism and newsroom culture generally is most closely captured by Pierre Bourdieu and his “field theory,” which holds that society is made up of a network of semiautonomous fields operating within a larger political field. A field is a network of historical and current relations (a profession such as journalism, for instance). Fields are spaces simultaneously of conflict and competition as agents compete to gain a monopoly over the species of capital that’s most effective in the field. Each field has its own regulatory logic and internal principles that govern the game on the field. Importantly, each individual field is marked by polarities: opposing forces within the field that compete for primacy, one over the other.2

Society, then, is an ensemble of relatively autonomous spheres of play that can’t be collapsed under any overall societal logic, like capitalism, postmodernism, or some larger theoretical model. Altering the distribution and relative weight of the different forms of capital within a field is tantamount to modifying the structure of the field. Therefore, fields have a historical dynamism about them; they have a malleability that avoids the determinism of the classical structures, such as class-based models. Fields change over time.

I argue that within the journalism “field” a primal conflict has been between access and accountability, Edwards Jones vs. Ida Tarbell. But this is hardly a fair fight. Nearly all advantages in journalism rest with access. The stories are generally shorter and quicker to do. Further, the interests of access reporting and its subjects often run in harmony. Powerful leaders are, after all, the sources for much of access reporting’s product. The harmonious relationship can lead to a synergy between reporter and source. Aided by access reporting, the source provides additional scoops. As one effective story follows another, access reporting is able to serve a news organization’s production needs, which tend to be voracious and unending. Access reporting thus wins support within the news hierarchy.

As access reporting circles the globe, accountability reporting is just putting on its shoes. Accountability reporting requires time, space, expense, risk, and stress. It makes few friends. Often, after one investigation is completed, accountability reporting must start from scratch. More than occasionally, accountability reporting must scrap a project altogether, further stressing a busy news organization.

Bourdieu’s theories play out in American newsrooms every day. The post-Kilgore Journal provides just one illustration. Ed Cony, the Journal’s managing editor from 1965 to 1970, seemed “to disdain routine business stories,” according to Edward Scharff, and set up a Page One operation of elite writers and storytellers who had his taste for almost anything else—witchcraft in Manhattan, life in a Scottish monastery, and so on. Indeed, when a new managing editor, Fred Taylor, took over, he felt obliged to issue an edict that the front page of the Wall Street Journal had to have at least one story about business or economics—every single day! On the other side, a Kilgore successor as CEO of Dow Jones, Warren Phillips, Cony’s boss, pushed relentlessly for hard news and scoops—especially after Reuters launched a financial newswire to compete with the Dow Jones ticker in 1966. Once, at a dinner of news executives, Phillips harangued the staff about the Reuters threat until Cony, his patience exhausted, finally said: “Oh, fuck Reuters.”3

The tug-of-war continued through the 1970s then shifted dramatically back to breaking business news under managing editor Larry O’Donnell, a former Detroit bureau chief. Scharff describes a tour of bureaus in which O’Donnell laid down the law in no uncertain terms in San Francisco:

Speaking in a low, flat monotone, O’Donnell accused them all of letting the newspaper down, of growing lazy, self-indulgent and indifferent toward the Journal’s true mission as the leading business newspaper. [The bureau chief] and his men had felt their main job was to produce work that was imaginative and informative, stories that were memorable and entertaining. But O’Donnell charged them with pursuing such stories mainly for personal glorification. All that would have to stop, he insisted. They would have to learn to be more on top of the news; they would have to make the Journal more of a newspaper. There would be emphasis on the nuts and bolts, less on the bizarre and irrelevant. In effect, what O’Donnell was telling them was to lower their own ambitions, precisely as he had done with his staff in Detroit.4

Office politics? Sure. But such is how news is defined within the field. A push for more “hard news” may sound like a muscular call to arms, but in many cases it represents a retreat from the hard work and risks of agenda-setting reporting. It may sound like a call for objectivity and fact-based reporting, but the question then arises: whose facts? Chances are, those of an institution that represents a particular set of interests whereas journalism—for all its faults, and when it is working right—represents the public’s.

The two tendencies represent different journalism subcultures. They rely on different sources—insiders versus outsiders, authorities versus dissidents, top executives versus fired executives (that is, whistleblowers). They require different skill sets, diplomacy versus confrontation. They even presuppose different worldviews. Access journalism might tend to accept institutions and systems as they are and seek to learn their internal goings-on; accountability journalism tends to question institutions and systems. One can be said to transmit orthodox views; the other, heterodox. Indeed, the differences can be listed:

| ACCESS | ACCOUNTABILITY |

| Fast | Slow |

| Short | Long |

| Elite sources | Dissident sources |

| Orthodox views | Heterodox views |

| Top-down | Bottom-up |

| Quantity | Quality |

| Investor | Public |

| Niche | Mass |

| Management friendly | Management unfriendly |

| Inverted pyramid | Storytelling |

| Functionalistic | Moralistic |

A final trait that defines access reporting is its inevitability. The public never need worry about its fate. There will always be news, and, competitive pressures being what they are, journalism will always chase it. Advocating for more “scoops” and “hard news” is like advocating for the tide to come in.

While it may seem that one is the “bad” kind of journalism and the other the good, that’s in no way the case. It is essential to know what people in power are thinking, and it is a nontrivial task to find out. Bob Woodward has been criticized during his post-Watergate career for taking part in “a trade in which the great grant access in return for glory.” Christopher Hitchens said of his work: “Access is all. Analysis and criticism are nowhere.”5 Yet most, including Hitchens, acknowledge its value. Neither is access reporting synonymous with flattering or favorable reporting. Indeed, it routinely stings powerful actors as part of its daily business. When Politico’s Mike Allen in 2008 asked Republican presidential candidate John McCain how many houses he owned (eight), McCain couldn’t immediately remember, and the scoop jarred a presidential campaign. Rather, what marks access reporting is its closed loop of sources, its top-down nature, and its lack of interest in systemic problems. Tethering itself to the never-ending flow of news events, access reporting allows powerful institutions to set the public agenda, to define the “news.” Most of all, one could say access reporting is defined by its insularity, an insistence on looking at its subject through frames set by the institutions on its beat. In business news, the access frame can be widened to include a focus on investor interests as opposed to the public interest.

Here some nuance is in order. Championing investors—particularly small investors—is a point of pride in business news, as well it might be. Some of its most celebrated stories, as we’ve seen, fiercely took on management for wasting, manipulating, or otherwise misusing the money entrusted to it by shareholders and did so in the face of fierce resistance from highly paid lawyers and public-relations specialists. Indeed, these stories were technically difficult, took a long time, and involved a high degree of risk to the news organization. Let’s move all of these shareholder-defense stories, which we can call financial investigations, under the accountability reporting frame. But financial investigations are a tiny fraction of conventional investor-oriented stories that explore a company’s prospects in its market.

During the mortgage era and afterward, the insularity of access reporting—its exclusive reliance on elite sources, its echo-chamber qualities—hamstrung business-press coverage of mortgage lenders and Wall Street. Indeed, the sped-up, incremental approach to news-gathering seriously impaired the business press’s ability to detect corruption in the mortgage market and aftermarket, but its insider focus was fatal.

But business journalism’s normative shift toward access reporting was driven by larger forces: the economy was transforming. Lipin’s remarkable run of scoops, for instance, came in part because there were more scoops to get. After the economic doldrums of the late 1980s and early 1990s, M&A activity exploded just as Lipin was arriving on the beat. After dipping to about 2,500 a year in the early 1990s, the number of North American transactions crept up to just under 5,000 in 1994 then soared to about 20,000 a year in 1998 and 1999. Total value of the deals shot from about $1.5 trillion in 1994 to $2.4 trillion in 1998—a record that has not been equaled even during the debt-fueled buying spree led by private-equity firms in the next decade.

More broadly, the rising prominence of the financial sector in the economy was becoming increasingly difficult to miss. Economists began to link widening problems of wage stagnation and income inequality to a new economic configuration that had been explicitly promoted by financial sector interests. Financialization had begun.6 Wall Street itself was expanding. What had been a group of closely held partnerships operating within a tightly knit, albeit highly competitive community where partners risked their own capital was morphing into a consolidating collection of globalized, publicly traded giants that risked other people’s money, took on extravagant levels of debt, and exerted increasing influence on the economy, the culture, and the political system.

And business news would be transformed by the great expansion of stock-market investing into the American middle class, which became increasingly curious about all things Wall Street. In Ida Tarbell’s day, only about 1 percent of the American public owned common stocks. The figure rose to 10 percent before the 1929 crash (with most of the increase coming in 1928), fell back again to the low single digits through most of the 1950s, and, through the 1970s, never reached above the mid-teens. Indeed, as late as 1980, only 13 percent of the country owned stocks. But by 1989, the figure had soared to 32 percent, and by 1998, more than half the country, 52 percent owned either stocks or equity mutual funds, either directly in their own accounts or indirectly in retirement and trust accounts.

Driving the change was a postwar expansion of the financial-services industry that transformed—and was transformed by—the American public’s changing views of credit, debt, stocks, and Wall Street. In 1994, Joseph Nocera wrote A Piece of the Action: How the Middle Class Joined the Money Class, which chronicled the metamorphosis of the industry that created the credit card, money-market accounts, discount brokerages, mutual funds, and the financial-planning business. Nocera argues convincingly that the inflation of the mid- to late 1970s forever changed the public’s attitudes toward money and investing. Americans flocked to money-market funds offered by the Reserve Fund (launched 1972), because the prime rate would hit an astonishing 20 percent (in 1980) while a Depression-era banking rule capped bank rates on deposits in the mid-single digits.7 And if inflation sparked the public’s search for yield for defensive reasons, the bull market that began in 1982 fed it for more positive ones. When the bull market began, the Dow stood at 776.92. By 1987, it would triple to 2570. After the crash that year, it would keep rising.

Nocera declared that the American middle class had pushed aside elites to take control of the stock market:

The financial markets were once the province of the wealthy, and they’re not anymore; they belong to all of us. We’ve finally gotten a piece of the action. If we have to pay attention now, if we have to spend a little time learning about which financial instruments make sense for us and which ones don’t, that seems to me an acceptable price to pay. Democracy always comes at some price. Even financial democracy.8

He was not alone in noting the cultural shift. Chernow, the Rockefeller biographer, would hail the middle class’s march into the markets. “Never before in American history have so many middle-class people enjoyed something at least faintly resembling the ‘private banking’ available to the rich,” he noted. “The culture of investing has become an abiding part of the American scene.”9 This triumphalist view, though, did not take into account a fraying safety net that pushed Americans increasingly into Wall Street’s arms for their retirement and other basic needs.

Their sanguine view of the stock market notwithstanding, these commentators might have even underestimated its strength. By the time Nocera published his book, the Dow had recovered from the 1987 crash and had reached 3,500, a gain of more than 40 percent beyond the precrash peaks. Then things really took off. The Dow would triple, rising to 11,000 by the end of the 1990s, and the middle-class march into the stock market would become a stampede. In Bull! A History of the Boom, 1982–1999, Maggie Mahar demonstrates that the first part of the bull market was driven by institutional investors, and it was only in the 1990s that stock investing truly became a common middle-class practice. From 1981 to 1985, the New York Stock Exchange estimated that the number of individual investors increased by just 6 million, to 36 million. The number of mutual-fund accounts increased fivefold during the 1980s (from 12 million in 1980 to 62 million in 1989 according to the ICI Fact Book), but the majority of these funds were not based in equities. From mid-1983 to October 1987, there were only two months when more money flowed into stock funds than bond funds. As late as 1992, the largest share of 401(k) money would still be invested in guaranteed investment contracts, fixed-income instruments offered by insurance companies.10

By the end of the 1980s, mutual-fund investors had more money in bond funds ($290 billion) than in stock funds ($240 billion) and twice as much again in money-market funds ($428 billion). In 1993, 401(k) investors began to put more than half their savings into stocks and stock funds.11 As bond yields fell and stock prices rose, stock funds grew, but even as late as 1994, Americans still allocated more to bond ($527 billion) and money-market funds ($611 billion) than stock funds ($852 billion). By the end of the 1990s, however, the public was heavily invested in the stock market, with $4 trillion in stock funds, compared to $812 billion in bond funds and $1.6 trillion in money markets.12

A Wall Street Journal story toward the end of the decade captured the changed national mood. The 5,000-word story headlined “The Soaring ’90s” included a profile of Shirley Sauerwein, a Redondo Beach social worker who aptly symbolized the middle class’s new relationship to the market. After never owning a share, in 1991 she heard about a local company that had signed a deal with Russia, opened a brokerage account, and bought one hundred shares at twelve dollars each.

Today, that company is MCI Worldcom Inc. Her original $1,200 now is worth $16,000, part of a mid-six-figure portfolio that includes Red Hat Inc., Yahoo! Inc., General Electric Co. and America Online Inc. “I’ve doubled my money in two years,” says Ms. Sauerwein, who is 55 years old. “I’m staggered, aren’t you? It’s amazing. You can’t make that in social work.” … Ms. Sauerwein’s stock-picking has been so successful that she’s cut back her social work to weekends and spends weekdays trading full-time from home. “I make a few buys and a few sells each day,” she says. Her goal: to make $150,000 in annual trading profits to build a financial cushion that she and her husband can live on in retirement.

Wall Street patter had become part of middle class discourse.

Along the way, Ms. Sauerwein has developed a few investing philosophies that speak volumes about how deeply ingrained “momentum” investing has become—and how utterly unfashionable it is to focus on “value” stocks. “All these people say ‘buy and hold,’” she says. “If a stock continues to decline, there comes a time when you better get off the boat.”

The lesson? “You have to sell your losers. If a stock goes up, it’s not because I was a whiz. And if the tape goes against me,” she adds, “I won’t stick around. I keep my losses to 10%.”13

One August day in 1995, around the time Lipin assumed the M&A beat at the Wall Street Journal, another pivotal moment in the evolution—one could say “revolution”—of business news came when the New York Stock Exchange for the first time in its history allowed a journalist, Maria Bartiromo of CNBC, to report live daily from the exchange floor. A native of Brooklyn’s working-class Bay Ridge neighborhood, Bartiromo had worked for Lou Dobbs on CNN’s MoneyLine when she was hired away by Roger Ailes, a Republican political consultant turned TV executive, who put her on the air.14 The deal with the NYSE came two years later, when she was twenty-eight, and her presence on the floor was an arresting image. Petite, attractive, and well-coiffed, equipped with clipboard and headset, she stood on the exchange floor surrounded by traders, almost all men, coming and going in their multicolored jackets (representing, savvy viewers would learn, different tasks or different firms). Occasionally brushed and jostled, she stood her ground, coolly rattling off information about the market and companies—analysts’ calls, earnings estimates, company news, and the like—looking up from the floor at the camera with an air of steely competence. The combination did not escape New York City’s tabloids, which soon captured the public’s feeling in a nickname: “Money Honey.”

What prestige the exchange assignment conferred on Bartiromo and CNBC, the journalist returned in kind, lending a once obscure and not particularly well liked institution a new air of glamour, vitality, urgency, modernity, and sex appeal. As retail investing increased, so did CNBC’s ratings, from fewer than 50,000 viewers in the early days to more than 250,000 by the end of the 1990s. Bartiromo’s was the attractive face of the people’s capitalism.

CNBC had started as a low-budget entertainment channel in 1980 but was recast as the Consumer News and Business Channel in 1988 when NBC, then owned by General Electric, struck a deal to lease the channel’s transponder. The network took off only after it won a successful bidding war against a partnership including Dow Jones (one of several botched business moves that would undermine the Wall Street Journal’s publisher, as we’ll see) for the longer-established Financial News Network, then in financial turmoil. The price was $157 million, which was seen as low even at the time.

The network’s lineup, then and now, consisted of a series of programs centered around the trading hours of the New York Stock Exchange from nine-thirty a.m. to four p.m.: On Squawk Box (named after an old fashioned intercom system used by Wall Street firms), three anchors discussed the day’s economic news and research reports and interviewed such Wall Street analysts as Goldman’s Abby Joseph Cohen and Prudential’s Ralph Acampora. The scene then shifted to Bartiromo and Opening Bell, where she would rattle off financial news and, significantly for her viewers, advance word of the latest Wall Street stock recommendations that she was able to learn from sources within the firms. At eleven, The Call focused on real-time market coverage. Power Lunch included interviews with top business executives. In the middle of the afternoon, Street Signs focused on trends and world events affecting markets. From three to five p.m. Closing Bell wrapped up the day’s market movements. After trading, the network would shift to a round-table discussion of stocks (the program now in the slot is Fast Money, which focuses on stocks for short-term trades). At six p.m. Jim Cramer, a former hedge-fund manager and founder of TheStreet.com, picked stocks on Mad Money.

The network is built around and plays to live television’s strength: immediacy. The screen is often a jumble of unconnected information. During trading hours, a “ticker” (a modern version of the machine invented by Edward A. Calahan in 1863 and unveiled in New York City in 1867) streams stock prices and price changes of individuals firms), as well as the Dow, the broader S&P 500, and the spot price for oil. The actual information is a recitation of reports, estimates, predictions, and data from Wall Street firms, hedge funds, economic consultants, government agencies (the Labor Department, the Fed), public companies, and other institutions.

CNBC saw itself as a force for the democratization of finance. Its executives claimed their mission was to provide everyday people the same information available to Wall Street professionals. In Fortune Tellers, Howard Kurtz profiles a CNBC executive, Bill Bolster, who articulated the network’s idealistic view of its mission. Bolster

liked to reminisce about his childhood in Waterloo, Iowa, where his father was a businessman who dabbled in the stock market. His dad’s only source of stock information was The Wall Street Journal, which arrived by mail two days late. It was hard to understand how his old man didn’t get taken to the cleaners. The time lag gave a huge advantage to the people who worked in an eight-block stretch of Manhattan, the sort of advantage that CNBC is helping to eliminate.

No wonder the traders felt threatened by this upstart network. … It was the good old white boys of Wall Street screwing around this shadowy system, which was threatened by the rise of electronic trading and the Internet and the searing spotlight of cable television.15

CNBC’s success lay to an important degree in its style as much as its substance. It put a human face on reporting that is essentially about dry numbers. In the 1990s Squawk Box was anchored by Mark Haines, a rumpled curmudgeon who bantered with and gave nicknames to cohosts and reporters. David Faber, “The Brain,” was handsome, articulate, and young. Another anchor, Ron Insana, was bald, bespectacled, and cerebral. Bill Griffeth, the old hand who had originally started at FNN in 1981, was avuncular and steady. Bartiromo, as noted, combined comeliness and outer-borough toughness. Becky Quick projected a financially savvy girl next door. Faber’s 2000 marriage to a CNN producer was the subject of much good-natured on-the-air ribbing and banter on Squawk Box. Insana’s decision in the late 1990s to forgo a toupee he wore on the air created a sensation.16

The network had been consciously modeled on ESPN’s Sports Center.17 The anchors and reporters provided pre-, post-, and mid-“game” reports, complete with sideline interviews with the players, but the game was the stock market. The public—enough of it—responded with enthusiasm. Anchors found themselves stopped on the street. Celebrities pronounced themselves fans: Regis Philbin, Charles Barkley, Andre Agassi, Saudi prince Alwaleed bin Talal. A Cleveland housewife started the “Hunks of CNBC” chatroom. Joey Ramone wrote a song about Maria Bartiromo.18

By the late 1990s, print journalists were trooping to the network’s studios in Englewood, New Jersey, to learn the secrets of CNBC’s soaring ratings and to pronounce that the network had captured the national zeitgeist. “CNBC is the TV network of our time,” said Fortune in a piece headlined “I Want My CNBC.” “The Revolution Will be Televised (on CNBC),” wrote Fast Company in a mostly laudatory 8,000-word article that called the network “the live feed of the new economy.” It said: “The 1990s witnessed a dramatic democratization of investing. And CNBC has driven that trend by taking some of the mystery out of the stock market and making it more accessible, by giving to anyone with a remote control access to the kind of information that used to be available only to big firms.” But even Fast Company couldn’t help but notice CNBC’s limitations, even as a deliverer of facts. “For one thing, it’s more opinion and analysis than news.”19

The Fast Company story was dated May 31, 2000—just in time for the revolution, such as it was, to end. The NASDAQ would soon have its historic crash from more than 5,000 to under 2,000 the following spring.

Alongside CNBC, a squadron of new business publications was launched to meet the growing interest in business and money. CNN launched its own financial news network. AOL opened a mutualfund center. Great metropolitan dailies ramped up staffing on their business-news desks, once newsroom backwaters. The Los Angeles Times, which had twenty to twenty-five business reporters in the early 1980s, had ninety by 2000; the Washington Post went from eighteen to eighty-one. The same was true for regional dailies: the Cleveland Plain Dealer went from nine to twenty-four or twenty-five; the Tampa Tribune; from two to fourteen. TV networks’ weekly coverage of the stock markets almost doubled between 1988 and 1999, from 152 to 296. In 1996 alone, twenty-two new personal-finance magazines were launched.20 The changes to business news were reflected in the names of the new outlets—SmartMoney (launched 1992), The Street (1996), Fast Company (1995), MarketWatch (1997)—all promising an insider’s perspective and a fixed gaze on markets and the latest business news, no matter how granular.

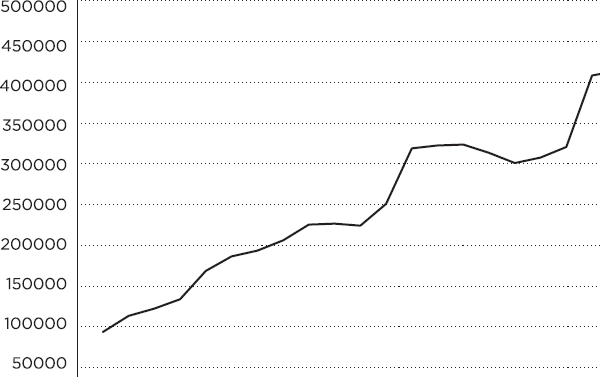

The total number of business-news stories published each year, according to ProQuest’s business-news database, ABI/Inform, jumped from about 168,000 in 1989 to 322,000 a decade later, a rise of 192 percent, and it kept rising, to 461,000 in 2009. Mergers-and-acquisitions news, once the concern of specialists, also took off, propelled in part by a dramatic rise in M&A itself. The volume of M&A stories grew from about 1,100 to about 4,600, more than 300 percent, from 1989 to 1999, according to ProQuest’s tagging system, which provides a rough guide. This rise was even faster than the number of deals themselves, which rose 187 percent, from about 12,800 to 36,800 during the period, according to Thomson Financial. (Both deal stories and deals dropped and then rebounded after the Tech Wreck in 2000, but continued to grow to about 4,900 and 43,000, respectively, in 2009.)21

Figure 5.1 The Rise of Business News: Total number of English-language business stories published, 1984–2010

Source: Author research, ABI/Inform Complete.

In the tug-of-war over the definition of business news, the 1990s brought a new emphasis on the investor-oriented side. Access reporting was ascendant. A successful run on the M&A beat became a career launching pad for individual reporters, and deal scoops helped to propel entire news organizations. The Financial Times rose to prominence in the U.S. market in the late 1990s, citing its scoops as evidence of its newsgathering prowess.22 Many of these came from Will Lewis, who became the youngest editor in chief of the Daily Telegraph in 2006 at the age of thirty-seven; he went on to a senior position in News Corp.’s News International unit. CNBC rose to even greater prominence, helped to a large degree by the scoop-getting exploits of David “The Brain” Faber, now one of the network’s top personalities.

As it was increasing its focus on investor concerns, business news, paradoxically, was narrowing. CNBC-ized news is characterized by two traits: a focus on insider, investor-focused news and speed. And while technology has obviously increased the velocity and volume of business news, the shift represents something less modern: a return to the business press’s early-twentieth-century roots as an intramarket information broker, reporting, as in the earlier days, from the inside out.

Actually, the term “revolution,” employed by Fast Company and others to describe CNBC and the popularization of stock investing, was far more apt than the gushing writers intended. Far from marking a break with the past or ushering in a new era, as the magazine implied, the rush to provide incremental, market-serving news was a revolution in the literal sense—a return to the past, to business news’s narrow origins as messenger service between market participants. What Dow, Jones, and Bergstrasser did with a special stylus and a platoon of messenger boys, Lipin, Faber, Andrew Ross Sorkin, and the like do with televisions and graphics.

It’s worth pausing here to examine the assumptions that underlie the theory of financial democratization. This paradigm envisions retail investors watching CNBC at home, receiving incremental information about markets or a particular company at the same time as Wall Street traders, and, empowered by online brokerage accounts, acting on it immediately. The idea of CNBC putting its viewers on an equal footing with Wall Street traders—let alone high-frequency trading programs—is beyond dubious. It’s a myth. In any case, a blow-by-blow stream of incremental stock-market news lends itself not to investment but speculation.

In the Tech Wreck of 2000, the democratization of financial news was revealed as one of a long string of episodes in which the retail investors, the “little guy,” turn out to be the “dumb money.” As Mahar illustrates, corporate insiders began to sell in earnest well before retail investors, those said to benefit from the CNBC-led information revolution, caught on. From September 1999 through July 2000, insider selling of large blocks of stock (at least $1 million or 100,000 shares) rose to $43.1 billion—twice as much as insiders sold over the same span in 1997 and 1998. The $39 billion in shares sold by insiders in the first six months of 2000 was more than in all of 1999. In the case of Global Crossing, for instance, insiders at the doomed fiber-optic company unloaded more than $1.3 billion from 1999 through November 2001. The company’s CEO, Gary Winnick, a former bond salesman under Michael Milken at Drexel, managed to sell shares worth $734 million, netting a personal profit of $714 million, long before the company would descend into bankruptcy in January 2002. The company’s 8,000 employees, by contrast, were unable to sell the company’s shares in their 401(k) in the period before the bankruptcy; their assets had been frozen. Indeed, most middle- and lower-income Americans who owned stocks in 2001 had only started buying them after 1995. Of households with assets of less than $25,000, 68 percent had made their first equity purchase in 1996 or later, and an alarming 43 percent in 1999 or later.23

The granular, insider approach and the focus on incremental news development instead of the larger forces driving events would likewise do CNBC’s viewers little good a decade later, on the eve of the mortgage crisis. The network, like the rest of business news, was forced to grope through the crisis with scant knowledge of the true nature of the subprime mortgage market, about which much more in chapters 6, 7, and 8. Its top stock picker and financial commentator, Jim Cramer, host of Mad Money, was roundly and justly mocked for declaiming, “Bear Stearns is fine!” in March 2008, two months before the Wall Street firm would crash and be rescued by a buyout subsidized by the Federal Reserve. And while Cramer and CNBC would later argue that he meant only that brokerage accounts—not the common stock—were “fine,” in fact, no part of that statement was true. Brokerage accounts, and any other money entrusted to Bear Stearns were in danger at the time. The firm, like the financial system as a whole, was not fine.24

And even granting whatever (dubious) benefit granular insider journalism provides to investors, it can be said to be fairly useless to the public at large. It faces the same limitations as its predecessors. It made business journalism ever more dependent on the very institutions it purported to cover. It gave business reporters less time to develop stories and made them less able—and less inclined—to challenge official versions of events; less able to examine systemic shifts that might pose dangers to even investors, let alone the broader society; and less able and less inclined, in the end, to do any kind of original reporting that did not emanate from an institution.

Even without taking into account the increased competition in the market for business news, Robert Shiller points out the undeniable attraction of the stock market as a generator of news to match the immediate needs of news organizations to provide incremental changes, “news,” for the perpetual news cycle.25 The stock market changes not just daily but by the second, perfectly matching the needs of live TV. It also offers drama, big players, and the possibility of fortunes being made or lost at any given moment. And it builds up and tears down prognosticators (Abbey Joseph Cohen, Mary Meeker, Henry Blodget) as the performance of their predictions dictates.

CNBC-ized, insider-oriented journalism—all too conveniently for its advocates within news organizations—had neither the time nor the resources for the arduous, risky, and indispensable investigative reporting of major financial institutions. For instance, Faber in his CNBC biography, claims credit for “breaking” the 2002 story of “massive fraud” at WorldCom, the corrupt telecommunications company. In fact, Faber was the first to report that WorldCom was ready to admit wrongdoing by restating its earnings. He did not through his own reporting unearth fraud at WorldCom. As Mahar points out, WorldCom at the time of his report was trading at sixty-one cents. “That’s the difference between being an investigative reporter and getting scoops,” Mahar quotes Herb Greenberg, a financial investigative reporter and CNBC commenter.26 For the general reader, it’s the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.

CNBC-ized news stands in opposition to Kilgore’s vision, the basis for business journalism’s original postwar expansion. Where Kilgore deemphasized what happened “yesterday,” deal journalism stressed what happened a few minutes ago. Where Kilgore counseled depth, deal journalism offers speed. Where Kilgore emphasized storytelling—narrative, character, detail—to make the complicated simple, deal journalism offered wire-service writing, the very pyramid style Kilgore abandoned. Kilgore disliked jargon. Deal journalism is marinated in it.

Access journalism is condemned to be forever taken by surprise by events. While it has been widely faulted for hyping the Tech Bubble (a charge, by the way, that Shiller finds overdone),27 it was completely taken by surprise by the staggering corruption that rocked the corporate world in the early 2000s: Tyco, Adelphia, and World-Com were all brand-name, closely covered companies that collapsed not just in financial failure but as criminal frauds.28

Enron was a special case in which accountability reporting did play a role in exposing what would become the era’s biggest criminal case. Fortune’s Bethany McLean is most often cited as triggering questions about the company’s finances with a March 5, 2001, article, “Is Enron Overpriced?,” which discussed the company’s complexity, mysterious transactions, erratic cash flow, and huge debt. Jonathan Weil, a Wall Street Journal reporter, raised questions about Enron and other energy-trading firms even earlier with “Energy Traders Cite Gains, but Some Math Is Missing” (September 20, 2000).

But even Enron, which had been on Fortune’s “most innovative” list of firms for six straight years, was not considered a shining moment for the business press. “It’s fair to say the press did not do a great job in covering Enron,” Steve Shepard, Businessweek’s editor in chief, said in 2002. “Enron was really a systemic failure of all the checks and balances we have on corporate governance: integrity of management, board of directors, audit committee of the board, outside accounting firm, Wall Street analysts and ultimately the press. And all of us failed.”29 But coverage of most of the scandals of the time was reduced to after-the-fact explanations, typified by a Wall Street Journal series in 2002 that ran under the plaintive headline “What’s Wrong?” The series won a Pulitzer—in the “explanatory” category.30

The so-called democratization of financial news turned out to be its opposite—news issued by institutions provided to reporters operating within the narrowest of frames. CNBC views business news solely through the frame of stock investors and, at best, reporters might challenge institutions on these terms. Even if they were inclined to stray beyond these boundaries, they lacked the time and support to do so. That’s just not what CNBC does. “Democratized news,” as proffered, is a welter of reports, presented in an atomized and granular format, that flow from government agencies, public companies, and investment banks. The news is stripped of the depth and context that “literate citizens” need to arm themselves with knowledge of a financial system that was growing ever-larger and playing an ever-more problematic role in their lives as economic actors and taxpayers, as citizens.

CNBC-ized news lends itself to a symbiotic relationship between institution and news organization, a closeness that blurs the line between the two. In October 2000, CNBC’s Mark Haines interviewed Enron’s chairman, Kenneth Lay, lobbing softball questions, such as, “So you are an old economy company using the new economy to great effect?” and “I imagine that the additional revenue pretty much goes straight to the bottom line. I mean, once you have it set up, there is very little incremental costs, right?” He then interviewed CEO Jeffrey Skilling the following April, asking at the outset: “Enron en route to greater earnings?” But before posing the question to Skilling, he added: “And in fair disclosure terms I will say that I own shares of Enron and have for quite some time, more than a year” (in other words, as Mahar points out, at the time when he interviewed Lay).31

In late 2006, Bartiromo herself became the story when the Wall Street Journal reported that Citigroup, a central player on any financial reporter’s beat, had ousted the head of its wealth-management unit, citing, among other things, his relationship with Bartiromo. The executive, Todd Thomson, had spent more than $5 million from his unit’s marketing budget to sponsor a program on the Sundance Channel hosted, among others, by Bartiromo.32 Thomson had also arranged for Bartiromo to speak to clients at luncheons in Hong Kong and Shanghai and flew back with her on the corporate jet. CNBC told the Journal that Bartiromo received permission for the trip and “payment was arranged.”33

But beyond the instances where reporters might have straddled ethical lines, CNBC and the financial system it covers often seem so close it’s hard tell where one leaves off and the other begins. In 2002, two finance professors at Emory University found an astonishing feedback loop between favorable comments made about individual companies by Bartiromo on her Midday Call segment and share prices of those companies: they jumped a tenth of a point within fifteen seconds and six-tenths of a percentage point (not a small number) within a minute.34 Indeed, the study, by Jeffrey A. Busse and Clifton Greene, found some stocks moving up slightly before the CNBC mentions, touching off a flurry of press investigations (which came to nothing).35

It is not uncommon for business reporters to follow the path of Edward Jones into the financial-services industry. Lipin, for instance, left the Wall Street Journal to run U.S. operations for Brunswick Group, a public-relations firm dealing with financial matters, including mergers and acquisitions. Likewise, few in financial journalism batted an eye when longtime CNBC anchor Ron Insana left in 2006 to start a hedge fund that invested in other hedge funds. The melding of media and market reached a high point in 1999, when CNBC purchased a stake in an electronic stock-trading company, Archipelago. News coverage, such as it was, focused on CNBC’s potential conflicts of interest as it would have to cover both Archipelago and a half-dozen electronic trading competitors. Not remarked upon was the fact that its partners in the deal included Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, and other Wall Street players (along with a unit of Reuters, another news organization, which already owned a electronic trading company). CNBC sold its stake a few years later (Archipelago was later bought by the New York Stock Exchange). But the fact that CNBC had become partners with the Wall Street firms it purported to cover was not perceived to be an issue,

A significant percentage of deal scoops are not dug out by industrious reporting but planted with reporters selected beforehand by the buying firm or its representatives. A carefully planned exclusive offers the Wall Street team control over the content and timing of the information. And while news organs beaten on the scoop will want to downplay the deal as much as possible, the importance of the news to its core audience tempers those desires. Hard feelings among competitors are smoothed out—or not—in the days following the scoop. In any event, there is little that competing reporters or news organizations can do about it. If offered a scoop the next time, they can hardly turn it down.

Once, while I was a reporter at the Wall Street Journal covering the paper and packaging industries, I received a call from the general counsel of a big industrial company I covered. He had important information for me; could we meet? Sure, I said. When? Now, he answered; he was calling from a payphone downstairs in the lobby of the World Financial Center, where the Journal was headquartered. A few minutes later, he strode off the elevator flanked by a PR man and another assistant. Unthinkingly, I offered them seats next to my desk in the newsroom, but the general counsel asked if there was an office where we could speak privately. He wasn’t being melodramatic. Behind closed doors, and with the grave tones of a man who was placing his career in my hands, he unveiled his company’s plans for an unsolicited, multi-billion-dollar offer to break up an already-announced cross-border merger between two leading competitors. The company was making a bold play. It wanted the attention that only the Journal could then provide. The understanding was that in return for the scoop, we would play it big.

My worldwide scoop the next morning led both A3, then the leading page for breaking news, and the “10-point,” the stack of top news stories blurbed on Page One. Almost as satisfying, my boss received a note from Lipin and a colleague congratulating us on the scoop but asking, with thinly veiled annoyance, that they be given a heads-up in the future since they could have contributed the expertise of their investment-banking sources. Hah, I thought. This only meant that I had beaten Lipin, the king, and the king was sore about it. It felt glorious.

And, unbelievably, it got better. The next day, the PR sources who had accompanied the executive on his clandestine visit the day before called for a congratulatory postmortem chat and told me in passing that he had been fielding anguished and angry calls from beaten reporters from other news organizations all that morning. They accused him, not incorrectly, of spoon-feeding me the scoop merely because I was at the Journal (in “our”—mine and my sources’—defense, I had cultivated this particular company for months). Until then, I hadn’t believed the euphoria I had been feeling could possibly be heightened, but hearing about my competitors’ howls of recrimination made it soar to almost unbearable levels. I didn’t known it was possible to feel this good—from a story! I grinned until my face hurt. I laughed and crowed to my pals in the newsroom, waving the paper, pointing out with the mock seriousness that if my story were any higher on the “10-point,” it would be off the page! That’s how high it was! The whole thing felt positively naughty. And unlike a successful investigative story, with its grand juries, arrests, and impeachments, here all was good. No one was going to jail. No one’s life was ruined. The opposite was the case. The buyer got its deal; the seller got paid; the bankers got paid; the other bankers got paid; the lawyers got paid; the other lawyers got paid; the PR firms got paid, etc., etc. And I got my scoop, clean as a whistle. The anguish and humiliation of my competitors, their fury and noisy protests, their career anxiety rippling over the phone lines—that was just a bonus, the sweet, fluffy center of this marvelous choux à la crème. Not long afterward, I was elevated to a better beat.

But access reporting, especially if unbalanced by accountability reporting, can present a dangerously distorted view of reality. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in what is perhaps the leading post-crisis book: Too Big to Fail: The Inside Story of How Wall Street and Washington Fought to Save the Financial System—and Themselves, by Andrew Ross Sorkin. Few business journalism careers have been as meteoric as that of Sorkin, who was assigned to the mergers-and-acquisitions beat of the New York Times at the tender age of twenty-two, when the paper was an afterthought in M&A coverage.36 In 2001, Sorkin developed “DealBook,” an innovative idea for a free daily electronic newsletter of major merger news. “DealBook” would attract more than 200,000 subscribers. Before he was thirty-two, he was awarded a column and made an editor of the business section. In 2010 “DealBook” employed more than a dozen reporters and contributors, including some of the most prominent in the business.37

One of the top-selling books on the financial crisis, Sorkin’s Too Big to Fail emerged from remarkable access to key financial leaders, including Henry Paulson, Ben Bernanke, Tim Geithner, Richard Fuld, Lloyd Blankfein, Jamie Dimon, and many others. The scenes are woven deftly together with previously reported and properly attributed material to form a streamlined chronology of the months leading up to Lehman’s failure and AIG’s rescue, as viewed from the executive suite. Reviews in the financial press were euphoric, and the book won a prestigious Loeb Award for best business book of the year. Too Big to Fail was later made into an HBO movie.

So close is the book to its characters, it sometimes records not just what they said but their thoughts as well. Here Sorkin relays Geithner’s during an early morning jog.

This is what it was all about, he thought to himself, the people who rise at dawn to get in to their jobs, all of whom rely to some extent on the financial industry to help power the economy. Never mind the staggering numbers. Never mind the ruthless complexity of structured finance and derivatives, nor the million-dollar bonuses of those who made bad bets. This is what saving the financial industry is really about, he reminded himself, protecting ordinary people with ordinary jobs.38

A book so reliant on the information of elites necessarily views the crisis entirely from their perspective and, in fact, casts its characters in mostly heroic terms, with a few exceptions, including Lehman’s Fuld, whose fall is depicted as merely tragic. The book steadfastly declines to look beyond the months leading up to the crash, so readers are left without the context to understand that nearly every individual or institution named in the book (Fuld, Bernanke, Geithner, Citigroup, AIG, etc.) played significant roles in causing the crisis in the first place. And the book refrains from explicitly characterizing the motives of its protagonists but does make an exception for Fuld, who is said to be “driven less by greed than by an overpowering desire to preserve the firm he loved.”39 This sense of disconnect, which obscures the larger picture, is clear in a scene at a 2008 dinner for the G7 Summit in Washington, in which Paulson shares his anxieties about leverage with Fuld:

“I’m worried about a lot of things,” Paulson now told Fuld, singling out a new IMF report estimating that mortgage-and realestate related writedowns could total $945 billion in the next two years. He said he was also anxious about the staggering amount of leverage—the amount of debt to equity—that the investment banks were still using to juice their returns. That only added enormous risk to the system, he complained.40

But it was Goldman, with Paulson at the helm, that strenuously lobbied for looser capital requirements in 2004, unleashing the sort of leverage that Paulson is seen fretting about. And it was Paulson’s Goldman (as Mark Pittman’s reporting for Bloomberg revealed in 2007) that did more than its share to create the defective securities that are seen melting down in Too Big to Fail. Sorkin explains none of this. Worse still is the treatment of Fuld and Lehman. The firm’s leading role in rise of predatory lending and subprime securitization goes unmentioned, despite, as we’ll see, an ample journalistic record, including in Sorkin’s own paper. Even Lehman’s attempts to manipulate its financial statements—which occurred during the narrow timeline covered by the book and were amply documented—go unmentioned.

Too Big to Fail is at once a monumental reporting achievement and an upside-down view of the financial crisis in which Wall Street, somehow, is the hero. As such, it exemplifies access reporting and its problems. Perhaps not surprisingly, when Too Big to Fail’s publisher held a book party at New York’s Monkey Bar in October 2009, many prominent CEOs and financiers named in the book attended, a circumstance for which Sorkin expressed gratitude in a report about the party.

“I must admit,” Sorkin wrote us this morning, “I was completely bowled over by the turnout. It was quite incredible to reassemble so many characters from the book in one room, all together. For a book that shows so many of these characters with their warts and all in the midst of the greatest panic of their lives, I am tremendously grateful that they came out to support me.”41