I’d love to buy The New York Times one day. And the next day shut it down as a public service.

—RUPERT MURDOCH

The whole notion of ‘long-form journalism’ is writer-centered, not public-centered.

—JEFF JARVIS, journalism academic

In early 2009, a few months after the Lehman crash, Robert Thomson, Rupert Murdoch’s pick to lead the Wall Street Journal, issued an internal directive headlined “A Matter of Urgency.” The memo discussed the need for the paper’s hundreds of reporters to step up their production of scoops.

The scoop has never had more significance to our professional users, for whom a few minutes, or even seconds, are a crucial advantage whose value has increased exponentially. … A breaking corporate, economic or political news story is of crucial value to our Newswires subscribers, who are being relentlessly wooed by less worthy competitors. Even a headstart of a few seconds is priceless for a commodities trader or a bond dealer.

The memo announced that “all Journal reporters would be judged, in significant part, by whether they break news” for the Journal’s wire service, significantly altering the career incentives for journalists at the most influential business publications in the world.

In assessing the post-crisis world of business news and news in general, the public is confronted with a confusing landscape. In both the subculture of business news and the larger news ecosystem there is plenty of cause for both hope and foreboding. As noted, the business press responded with vigor from mid-2007 onward as, one by one, starting with Bear Stearns in early 2008, the central institutions on its central beat started to crumble. The entire subprime lending industry collapsed as though struck by plague, starting in the spring of 2007 with New Century Financial, a notorious operator. With financial markets gyrating wildly—the stock market plummeted in summer of 2007, recovered in the fall, and dived again in the spring—the financial press was in full alert mode. Soon, the state of Wall Street banks—first Bear Stearns, then Lehman Brothers—became a running emergency as investors saw the huge amount of mortgage-related debt on their balance sheets and waged fierce arguments about their solvency. David Einhorn and Bill Ackman and other hedge-fund managers who had taken “short” positions against the banks and bond insurers argued that Wall Street’s accounting practices were seriously flawed, and the balance sheets of financial institutions, grossly misleading. Wall Street, led by Lehman’s CEO, Richard Fuld, argued just as fiercely and called for a government crackdown on short-sellers, saying their accusations and dire predictions were intended to destroy confidence and become self-fulfilling prophecies.

True, some CNBCized elements of the press were hampered by a poor grasp of the nature of the subprime market. “Bear Stearns is fine!” CNBC’s Jim Cramer famously called out on March 11, 2008. Less than a week later it had been bailed out by the Federal Reserve, its assets sold to JP Morgan Chase.1 But when Lehman finally collapsed into bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, business news treated it as the monumental calamity that it was, using banner headlines across their front pages of a width normally reserved for declarations of war. “Worst Crisis since ’30s, with No End Yet in Sight,” read the Journal on September 18, 2008.

Business-news organizations continued to turn out quality work investigating and explaining what had happened—exemplified by the reporting by the New York Times and Bloomberg discussed in chapter 9 but certainly not confined to that. In this book, I’ve attempted to highlight a journalism practice—accountability reporting, as opposed to individual reporters—because it’s the practice that counts. Still, a few individuals deserve mention for continuing to probe a story that keeps yielding startling and disturbing revelations long after the majority of the business-news establishment had moved on. These include Gretchen Morgenson and Louise Story for the Times, Matthew Goldstein for Businessweek and Reuters, Bob Ivry for Bloomberg, Steve Kroft for 60 Minutes, Lowell Bergman for Frontline, and Mike Hudson, who as of this writing is a senior editor with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a philanthropically supported news organization. The McClatchy chain demonstrated, among other things, the tight ties between predatory lenders and Goldman Sachs. The Miami Herald exposed how Florida regulators approved thousands of mortgage brokerage licenses for convicted criminals. Special mention should be reserved for Jessie Eisinger and Jake Bernstein of the nonprofit investigative-news organization ProPublica for their groundbreaking “Magnetar” series cited in chapter 9, which exposed shocking lawlessness in the mortgage after-market.2 The work was awarded the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting—the first and probably the only crisis-related work to win a Pulitzer. Matt Taibbi exploded onto the financial scene in July 2009 with his investigative polemic “Inside the Great American Bubble Machine,” in Rolling Stone, which compared Goldman Sachs to a “giant vampire squid.” Michael Lewis wrote a riveting and hilarious look at the short-sellers who understood and profited from a corrupted system in the now-defunct Condé Nast Portfolio, later expanded into his book The Big Short. This list is hardly exhaustive.

However, even as it is important to acknowledge this invaluable forensic work, it is equally important to acknowledge that it has also been lonely work. It would be gratifying to report that the financial crisis provoked a cultural shift within the profession that covered the financial system, but that is far from the case. Indeed, mainstream business news generally moved on from the greatest business story in several generations with, it is fair to say, stunning complacency and few backward glances to determine exactly where it fit into the system that had so recently collapsed. As Ryan Chittum noted in a comprehensive review of post-crash reporting, the business press in general was guilty of “missing the moment”:

The press has done a decent job in the three years since explaining the … easy credit story, but a poor one of investigating the Wall Street–boiler room nexus that implemented what happened in neighborhoods.

This was particularly evident when the press presented homeowners as being just as culpable for the housing bubble and fraud as the financial institutions that aggressively lent to them. Plenty of stories focus on the huge amount of debt piled onto households in the last thirty years. But relatively few of them focus on why households took on so much debt in the first place. The conditions of the crisis were created by the decades-long struggles of the middle and working classes.3

The failure was one not of industry but of imagination. The leaders of the business press have shown that they clearly understood they were reporting the greatest financial story of their lives. But only a few understood they were also reporting the greatest financial scandal.

Indeed, because of weak reporting even after the crisis on mortgage-industry lawlessness, business news on occasion has been guilty of perpetuating the pernicious myth that irresponsible or unethical borrowers—particularly minority borrowers—drove the system to crisis. CNBC’s Rick Santelli’s 2009 tirade against “losers’ mortgages” helped to trigger the Tea Party movement, based in part on misplaced resentment against homeowners facing foreclosure. But even the mainstream Businessweek, now owned by Bloomberg, provoked a storm with its February 25, 2013, issue when, for an otherwise inoffensive story on a new housing boom, its cover depicted caricatures of blacks and Hispanics reminiscent of early-twentieth-century race cartoons, all swimming in cash as it flooded a house.4 The magazine’s editor apologized, but the slip suggested fundamental misunderstandings of the mortgage crisis held by even elite business editors five years after the fact.

Clearly, there is work to do. It is my view that the borrower-lender exchange during the mortgage era remains the least understood, most understudied—and most pressing—area of inquiry left over from the crisis. Again, it must be conceded that accountability reporting after the crisis has been seriously hindered by one the most glaring failures of the post-crisis social and political landscape: the inexplicable absence of a single criminal prosecution to be brought against any major figure either among mortgage lenders or on Wall Street. The Obama administration and its attorney general, Eric Holder, must bear primary responsibility for this law-enforcement failure, which has left a corrosive void in the public’s sense of justice about the event and, not trivially, has deprived the public of information about the crisis that could help better understanding. As of this writing, five years after the Lehman crash, two years after the filmmaker Charles Ferguson memorably called attention to the problem at the Oscars, and more a than a year after President Obama, in a State of the Union speech, announced a cross-agency law-enforcement group to prosecute mortgage-era fraud, white-collar law enforcement in the United States remains at a low ebb. Accountability reporting and public understanding suffer as a result. As we’re learning, only an indictment has the power to change a narrative. Civil settlements won’t do.

But, of course, the business-news landscape has been transformed in the years leading up to and since the crash. While the general news landscape remains in a state of dramatic disruption, the financial health of business-news outlets is more mixed. Major metropolitan dailies, particularly the Washington Post and Los Angeles Times, have dramatically cut back on business coverage because of financial problems at their parent companies. In 2006, the Forbes family, for the first time, was forced to sell off a stake in Forbes’s weakened parent company to outsiders and then sold the magazine’s famous Fifth Avenue headquarters. In 2009, Fortune trimmed the number of issues it published annually by a fourth, and in early 2013 it was part of a larger list of Time Warner magazine titles slated for sale or spin-off. On the other hand, Bloomberg and Reuters, wire services that had once been business-news backwaters, have considerably strengthened their newsgathering operations, adding long-form features and beefing up investigative capacity. Reuters’s 2012 investigations into collusion with competitors at Chesapeake Energy led to the ouster of its chief executive, Aubrey McClendon.5

Likewise, the New York Times, though battered financially by the Internet, maintains a business desk that more than holds its own against larger competitors and that includes formidable investigative assets. David Kocienewski’s series on tax avoidance at General Electric and elsewhere in 2011 and David Barstow’s epic 2012 blockbuster on bribery and cover-ups at Wal-Mart stand as classics of investigative reporting in any era.6

On the other hand, the Wall Street Journal under Rupert Murdoch is greatly diminished both in its influence and, certainly, in its ability to produce great long-form narratives and investigations on markets, corporate behavior, and the economy. Of course, there are exceptions and always will be across a staff that numbers in the hundreds. The paper’s accountability reporting on Internet privacy, for instance, has been unparalleled.7 But the paper itself explicitly moved away from business and economic coverage—the better, it said, to compete with the New York Times on general news—and halved the number of leders it produces to one a day. Sometimes there are none at all. In my opinion, and I’m not alone, the leders by and large lack the depth and certainly the breadth of those of earlier eras. Today’s paper, with its Page One festooned with breaking news from one institution or another, has moved toward the narrow investor-centered product of an earlier era. But, as we’ll see, the retreat from long-form journalism is not an accident. It’s entirely by design and of a piece with Murdoch’s long-stated antipathy to it as a form, as well as to the idea of newspapers’ role as watchdogs in the public interest.

For what it is worth, the Journal routinely won Pulitzer Prizes starting in the Kilgore era and from 1995 to 2007 won at least one in all but two years, including a prestigious public service award for an extraordinary, and extraordinarily difficult, story about the illegal back-dating of options to benefit corporate executives. As of this writing, the paper has gone six years without a prize for the news operation (it won two for editorial writing). Pulitzers obviously aren’t the only measure of quality, and prize-mongering is to be deplored. But, if nothing else, they are a measure of effort and ambition, and so the post-Murdoch shutout is indeed telling.

On the positive side of the ledger, a new generation of business and financial websites has helped to—partially—offset losses in the news-gathering apparatus of mainstream outlets. Sites like Calculated Risk, Naked Capitalism, and the Big Picture aggregate important news, offering analysis enhanced by a clear point of view that expresses a sense of moral outrage and frustration largely absent from conventional reporting. Some of these sites rose during the mortgage era and contributed important and groundbreaking analysis that pointed to abuses and dangers in the system. For example, Yves Smith, a pseudonymous blogger at Naked Capitalism, and others at the same site offered early details of Magnetar’s activities, information contained in Smith’s 2010 crisis book, ECONned: How Unenlightened Self Interest Undermined Democracy and Corrupted Capitalism. Business Insider, launched in 2009, has become a popular and, lately, profitable business and finance site that aggregates material from elsewhere and adds lively expert commentary and analysis, most notably by Joe Weisenthal. Founded by Henry Blodget, a former Wall Street analyst censured and barred by the Securities and Exchange Commission for his role in the tech crash, the site has been criticized for its aggregation methods and for its frequently misleading sensationalism, but it has also shown a flair for click-bait headlines and the digital medium generally. Deal-breaker, published by Breaking Media, has developed a large following with its cheeky blend of Wall Street gossip and jargon-free, conversational commentary on finance. Mainstream media added a few breakout stars to the blogosphere, Felix Salmon of Reuters, for instance, and Paul Krugman of the New York Times added blogging to his credentials. Meanwhile, the field of economic commentary has been greatly enhanced by influential blogs with credentialed economists, including Brad DeLong, Greg Mankiw, Mark Thoma, and Simon Johnson, and journalists, including Mike Konczal, Ezra Klein, and others. These writers are playing a significant role in shaping policy debates.

Special mention should be made of the digital-journalism pioneer Huffington Post. Founded by Arianna Huffington, the site has drawn heavy and well-deserved criticism for its reliance on unpaid bloggers and its editorial style of heavy-handed aggregation of material both sober and tawdry. However, the tabloid style and click-dependent model has allowed the site to develop a small staff that contributes important original, sometimes muckraking reporting on the financial system and the economy, particularly labor issues and unemployment, topics woefully undercovered in traditional media.

It should be said that all of the new entrants put together do not offset the losses of major metropolitan newspapers, like the Washington Post and the Los Angeles Times, which together have lost nearly 1,000 journalists and have severely cut back on business coverage. It is the difference between journalism on an artisanal scale and an industrial one.

But even granting the value of new entrants and the promise of journalism’s digital future, if accountability reporting is to be the public’s lodestar through the current journalism storm, and I believe it should be, it faces threats from two powerful forces now dominating the new ecosystem. One is old: corporatism, with its longstanding hostility to the difficulties, risks, and subversive nature of accountability reporting. The other is new; let’s call it “digitism,” which seeks to dispense with traditional journalism forms mainly because digital models cannot accommodate them. While they come from different intellectual traditions, they have meshed together with an uncanny exactness to undermine what is most valuable in the news.

Corporatism couches its opposition to accountability reporting as faux populism, deriding such vital tools as long-form stories as “boring,” “self-indulgent” prize-mongering foisted on an unwilling public by journalists more interested in winning approval of their peers than in serving the public. This type of criticism has a long history. Indeed, there was no more severe critic of American journalism’s alleged elitism, “arrogance,” and “cynicism” than Al Neuharth, the defining executive of Gannett, a company that combined an anti-adversarial form of journalism with ruthless newsroom cost-cutting into a successful business strategy—and did more than perhaps any other newspaper company in history to strip the American landscape of quality local news. In his columns and his memoir, Confessions of an S.O.B., the founder of USA Today relentlessly attacked journalism’s supposed pretensions and the alleged arrogance of individual journalists. He blasted “cynicism” and “elitism” as the industry’s greatest problems and routinely lambasted noxious elites “east of the Hudson and east of the Potomac” as their source.8

In the place of the cynicism he saw in professional journalism and its reporting on “bad and sad,” Neuharth aimed to turn USA Today, founded in 1982, into a fount of something he called the “Journalism of Hope.” An expression of market populism’s encroachment into journalism, the Journalism of Hope was marked chiefly by a refusal to judge. Or as Neuharth put it: “It doesn’t dictate. We don’t force unwanted objects down unwilling throats.” In Neuharth’s view, as Thomas Frank acidly put it, “Elitism was a sin committed by authors, not by owners.”9

Neuharth’s 1989 memoir is filled with attacks on so-called elite papers, including, of course, the New York Times (which suffered from “intellectual snobbery”) and, especially, the Washington Post (which exuded an “aura of arrogance”); both made the book’s list of “10 most overrated newspapers,” along with the Miami Herald, the St. Petersburg Times, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and others that we recognize today as having been the most aggressive, stiff-necked, and independent papers in the nation. Fatefully, Neuharth also listed the Louisville Courier-Journal and the Des Moines Register, two legendary statewide papers that Gannett had not long before acquired and was well on its way to gutting in the name of its famously high profit margins.

Sam Zell, who has resented serious journalistic scrutiny over his long career as a vulture investor, implemented his anti-intellectual and, frankly, juvenile ideas about journalism when he took over the Tribune Company in 2007 through a leveraged buyout that became by consensus the most disastrous deal in American newspaper history. Installing a former rock-and-roll radio executive and other nonjournalists in key posts, Zell and his team cast their efforts as a campaign against what he called stodgy thinking and “journalistic arrogance.” Instead, they turned former bastions of serious reporting—with, of course, flaws, like everywhere else—into something resembling a frat house, complete with poker parties, juke boxes, and pervasive sex talk that frequently crossed into sexual harassment. A 2010 New York Times story on Tribune Company’s travails quoted James Warren, the former managing editor and Washington bureau chief of the Chicago Tribune: “They wheeled around here doing what they wished, showing a clear contempt for most everyone that was here and used power just because they had it. They used the notion of reinventing the newspapers simply as a cover for cost-cutting.” The Zell-led team drove the company into bankruptcy, from which it emerged far weaker but free, at least, of Zell.10

Most consequentially, Rupert Murdoch over the course of a long career has made clear his hostility to reporter-driven journalism in the public interest, calling it a self-indulgent, elitist pretension done to advance careers and impress peers. During and after News Corp.’s fateful 2007 bid for the Wall Street Journal’s parent, Dow Jones, Murdoch and his allies frequently cited long-form stories on Page One as a problem in need of a solution. “If I may be so bold as to say that in this country newspapers have become monopolized,” Murdoch told a group of Wall Street Journal editors soon after taking over the paper. “They’ve become—some of them have become pretty pretentious and suffer from a sort of tyranny of journalism schools so often run by failed editors.” The crowd laughed nervously. Speaking of the New York Times, he said: “One of the great frailties, I think, of that paper, is that is seems to me their journalists are pandering to powers in Manhattan. You know [pausing for dramatic effect] reporters are not writers in residence.”11 His biographer, Michael Wolff, reports Murdoch’s views that journalism’s main problem remains an inflated image of itself. “The entire rationale of modern, objective, arm’s-length, editor-driven journalism—the quasi-religious nature of which had blossomed in no small way as a response to him—he regarded as artifice if not an outright sham.”12

Murdoch’s ideal newspaper was the Mirror, a bawdy and rambunctious British tabloid under the postwar editorship of Harry Guy Bartholomew, whom Murdoch called “a great editor,” meaning, in Wolff’s words, “not a great finder of facts but a great packager, showman, and drinker.” In the Murdoch paradigm, tabloid-style journalism—commodity news repackaged under a cleverly written headline—is invariably described as vigorous, unpretentious, bawdy, fun, and, importantly, virile. This healthy, masculine form of journalism is juxtaposed against the kind that labors under unsexy names like “long form” or “public service” and is usually described as effete, elitist, and, invariably, feminine. Journalists who perform it are sissies. Or, as David Carr summarizes Sarah Ellison’s findings: “Again and again, the new owners of The Journal see the newspaper’s critics as left-leaning pantywaists and ‘Columbia Journalism School’ types.”13

Thus, it is not surprising that Murdoch’s chief target after taking over the Journal was long-form journalism. The Murdoch-installed managing editor, Robert Thomson, quickly moved to further dismantle Kilgore’s Page One storytelling factory, which had already lost its autonomy under Paul Steiger in 2000. Thomson told a gathering of reporters that “a journalistic culture based solely on one story or two stories in the paper today is skewed in the wrong direction. Journalism is a lot more complicated and a lot more diverse than that. And I think people have to be doing several things, several types of stories at the same time. And that’s a challenge, but that’s a challenge every journalist around the world at every news organization is facing.” At another gathering of reporters, he warned staffers to be more productive and said, in a phrase that would resonate, that some stories seemed to have “the gestation period of a llama,” that is, nearly a year.14

Thomson’s “Matter of Urgency” memo, quoted at the start of this chapter, was part of a larger reorganization at the world’s leading financial daily that eroded the heart of Bernard Kilgore’s legacy of literate, in-depth, polished daily reporting that appealed to readers’ intelligence and offered them original stories unavailable elsewhere. Previously, Journal reporters, as distinguished from those of Dow Jones’s wire service, had been judged on their ability to produce a range of stories, scoops, features, exposés, and so on. But the ability to produce long-form in-depth “leders”—considered an elite function—separated a Journal reporter from the wires. Now, incentives tilted decisively toward short-form scoops. As one journal reporter put it in 2010: “We give them three times as many things that are completely unimportant.” Sure enough, the length of Journal stories plummeted after the Murdoch takeover. Page-One stories of more than 1,500 words fell from nearly 800 per year in 2007 to fewer than 300 in 2011. Stories of more than 2,500 words—often the greatest tales—dropped from nearly 175 a year to just a handful.15

As 2013 dawned, Murdoch appointed a new editor, Gerard Baker (and celebrated by pouring a bottle of champagne over Baker’s head), and the turn toward access reporting became even more pronounced. In an internal memo to “All News Staff” under the subject line SCOOPS, a top editor drove the message home:

Colleagues:

Nothing we do as a news organization is more important than maintaining a steady flow of scoops. Exclusives are at the very heart of our journalism and of what readers expect of us. As Gerry [Baker] noted in his New Year’s note, “Scoops are the only guarantee of survival” in a highly competitive news arena.

And a week into the New Year, we want to underscore the need for a renewed, and ongoing, push for scoops. …

With our ability to gain access, we should also be regularly conducting exclusive interviews around the world with newsmakers from government, business and finance. … Success at obtaining scoops, and avoiding being scooped by competitors, will be central to how each of us is directly evaluated—just as it is central to how rightfully demanding readers evaluate us every day. As you dive into 2013, please keep this crucial need at the forefront of your thinking. …

Thanks in advance for your accelerated efforts.

Later that spring, a veteran Journal investigative reporter, Ann Davis Vaughan, breaking the silence that financial vulnerability imposes on most reporters, published an essay described the debilitating effects on accountability reporting imposed by the new regime.

Not long after Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. closed a staggering $5.6 billion takeover of our public company, Dow Jones, in 2007, he and his deputies began publicly disparaging the investigative reporting culture that had drawn me to the Journal. They all but called our business coverage boring, and declared that the secret to arresting the decline in newspaper readership was to run more general interest news.

“Stop having people write articles to win Pulitzer Prizes,” Murdoch said at a conference. “Give people what they want to read and make it interesting. …”

The first change I noticed was that editors I respected and had worked with for years—those still standing after a purge—came under heavy pressure to simplify stories that were premised on nuanced points. Editors sent memos stating that stories needed to break news and carry a headline of just a few words to get prominent play. Nuance was suddenly our enemy, even if it was the truth.

Vaughan relays an experience in which she had returned from the second of two reporting trips to the United Kingdom and the Gulf Coast for a story on a collapse in the global oil-refining business. While not breaking news, it was a bread-and-butter Journal story that explained in a compelling way a complex problem with broad investment and economic implications. Instead, she was pulled off for a stint monitoring general news and wound up assigned to a story about Colorado parents who falsely claimed their six-year-old had been swept away in a helium balloon. Vaughan chased the story, known as “Balloon Boy,” which was already overrun by dozens of other outlets and bloggers. A few days later, a disturbed army psychiatrist massacred fellow soldiers at Fort Hood in Texas. And so it went. The refining story languished until two and half months later—when the New York Times ran a similar story. Davis was scooped. She left to start her own research firm.

Murdoch and Thomson love talking about how journalists at establishment papers feel entitled and presumptuous. I will concede this is sometimes true. But I would turn their point around: News Corp. feels entitled to ask highly skilled journalists to produce commodity journalism in return for a relatively low salary in a dying industry. If talented business journalists care at all about the long-term portability of their skills in a shrinking media world, succumbing to pack journalism in a crowded general news category is no way out. It makes senior, expensive reporters expendable. That was not the direction I wanted my career to be heading.

My career shift is not necessarily good for business journalism or Main Street investing. Increasingly, investors are paying investigative reporters like me to go digging exclusively on their behalf rather than publish our findings for a wider audience. But the exodus is inevitable as newspapers offer less space, time, and money for investigative reporting. At least the investment world, which is infamous for missing red flags and failing to ask painfully obvious questions, is now getting more of it.

Vaughan titled her essay “The Gestation Period of a Llama.”16

It is not only ironic but entirely fitting that the most damaging blow ever delivered to Murdoch’s News Corp. would come not from shareholders, regulators, or law enforcement but from forthright investigative journalism. Nick Davies and his colleagues at the Guardian explored for years allegations of phone hacking, bribery, and hush-money payments at the most notorious of News Corp.’s British tabloids, News of the World, which, along with other News Corp. media properties, entertained its audience with gossip while intimidating U.K. political and social elites who might have challenged Murdoch or his business interests. In July 2011, Davies and the Guardian revealed that among the thousands of the paper’s hacking victims was a missing thirteen-year-old girl, Milly Dowler, who at the time was the subject of a nationwide police search. She later turned up murdered. The story gripped the public’s imagination and, along with subsequent revelations in the Guardian and elsewhere, triggered a cascade of investigations, parliamentary hearings, and a public uproar over Murdoch’s influence so loud that it became what commenters called “the British Spring.”17

In researching this book, I had a chance to leaf through quite a bit of media criticism and theory from not so long ago, a body of literature that over the course of my working years I had never seen before. It was, so to speak, news to me. I was struck mostly by the well-meaning and thoughtful criticism from the 1980s and 1990s, before the main-streaming of the Internet, that worried about the perceived (and obviously real) imperiousness of corporate media and its concentration in a few not especially public-spirited hands. Ben Bagdikian, the venerable media critic, paved the way with his landmark survey of media consolidation, The Media Monopoly, in 1983 and updated it in 1989 in an article in the Nation that asserted the problem had only gotten worse: “As the world heads for the last decade of the twentieth century, five media corporations dominate the fight for hundreds of millions of minds in the global village.”18 Many thinkers called for a more responsive and open form of communication between press and public, a more permeable relationship, so to speak, more “horizontal,” less top-down. Columbia’s James W. Carey, a cultural critic and communications theorist, argued for what he called a “journalism of conversation,” which he described as a sort of connective tissue of democracy:

Republics require conversation, often cacophonous conversation, for they should be noisy places. That conversation has to be informed, of course, and the press has a role in supplying that information. But the kind of information required can only be generated by public conversation; there is simply no substitute for it. … A press that encourages conversation of its culture is the equivalent of an extended town meeting. However, if the press sees its role as limited to informing whoever happens to turn up at the end of the communication channel, it explicitly abandons its role as an agency of carrying on the conversation of the culture.

Such a press treats readers as objects rather than subjects of democracy.19

When the Internet wrecked havoc on news-media business models, news professionals reacted with shock and dismay, but others saw rough justice. For a vanguard of technologically oriented news thinkers, the news organizations’ financial problems were the market’s verdict on imperious, bureaucratic, play-it-safe reporting. In the chaos, these digital-news advocates, intellectual heirs in a sense to Carey, saw an opportunity to sweep away corporatist journalism—all of it—and begin anew, based on a networked model that would allow a new flowering of citizen participation in the news.

This new wave of digital-journalism thinkers created a body of ideas that took hold around 2008 to 2010, a time of maximum panic in the news industry. I called it the “future of news” (FON) consensus.20 According to this consensus, the future points toward a network-driven system of journalism in which news organizations will play a decreasingly important role. News won’t be collected and delivered in the traditional sense. It would be assembled, shared, and, to an increasing degree, even gathered by a sophisticated readership. This model posits an interconnected world in which boundaries between storyteller and audience dissolve into a conversation between equal parties (the implication being that the conversation between reporter and reader was a hierarchical relationship).

At its heart, the networked-journalism consensus was anti-institutional. It believed that traditional news organizations were unsustainable in their current incarnation and that, in any case, a networked model, which it believes is more participatory and democratic, was preferable. Clay Shirky, a leading journalism academic, put it vividly in Here Comes Everybody, his 2008 popularization of so-called peer production, the participation of amateurs in professionalized activities: “The hallmark of revolution is that the goals of the revolutionaries cannot be contained by the institutional structure of the existing society. As a result, either the revolutionaries are put down, or some of those institutions are altered, replaced or destroyed.”21 Under this consensus, news is seen as an abundant and nearly valueless commodity. News organizations would become less producers of news than platforms of community engagement, and journalists would act as curators and moderators as much as they would reporters. Digital news, as originally conceived, was meant to be free—the better to interact with readers in a global “conversation.” The thinking was that digital advertising would support the news operation as print ads have traditionally done. The higher the traffic to a news site, the more revenue that would flow. Elements of this consensus were adopted across the news industry, which, disoriented and unfamiliar with this new digital world, fatefully decided not to charge online for the same news its readers paid for in print. Meanwhile, news organizations frantically sought to adapt to the new tools, work habits, and idiom of the Internet.

Many of the ideas of the new journalism have been put in practice under the rubric of “digital first,” the name of a company as well as a philosophy, which would radically revise what news organizations do. As Jeff Jarvis wrote:

Digital first resets the journalistic relationship with the community, making the news organization less a producer and more an open platform for the public to share what it knows. It is to that process that the journalist adds value. She may do so in many forms—reporting, curating people and their information, providing applications and tools, gathering data, organizing effort, educating participants … and writing articles.22

“Digital First” was adopted as the name of a company that manages the Journal Register Company and Media News Group, founded by William Dean Singleton, which publishes the Denver Post and fifty-two other newspapers, or “multiplatform products.” Digital First implemented many innovations designed to more fully involve the public in the news and, according to the company’s website, establish “a baseline of trust” between news organization and audience. For instance, it turned the newsroom of its Register Citizen, in Torrington, Conn., into a public café, open from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m., and invited readers to wander through the newsroom to “find the reporter that writes about their community or area of interest—or editors—and talk about concerns, ideas, questions.” The Register Citizen’s story meetings were opened to the public, “at a conference room table at the edge of the cafe, and the community is invited to pull up a chair, listen in or participate,” and simulcast on the paper’s website. “Digital first reporting,” meanwhile, “increasingly means, for us, that the audience knows what we’re working on at the assignment stage or before (as in, the audience participating in the discussion that determines assignments).”23

But there are two problems with the model. First, the question of open newsrooms aside, the free-content system rewarded quantity—the more stories published, the more “inventory” against which to sell ads. And since no one can predict in advance what stories will generate traffic—an exposé of municipal corruption that took three months to produce or a video of a cat caught in a tree that took three minutes—incentives all run toward posts that can be done quickly. Free news, it turned out, created a downward spiral of quality. Long-form exposés could still be done under the new system, but under the logic of free news, from a business point of view, they made no sense.

The second problem was that Web ad rates—contrary to predictions—fell significantly as the Internet churned out a nearly limitless supply of ad space and Internet giants drove down prices with ruthless efficiency. Since no one knows in advance which post will generate traffic, the logic of the model calls for ever-increasing quantities of “content.” Put simply, more posts equals more traffic equals more revenue. The free structure makes inevitable what I call the “Hamster Wheel.” To achieve growth, the wheel must spin at ever-increasing velocity. What’s more, even news organizations with successful websites, like the New York Times, which (depending who’s measuring) reported 34 million unique visitors a month, or the Guardian, with even higher figures, must compete with the likes of Facebook, which has more than a billion active users.24 The digital ad game became a model for ever-increasing effort to produce ever-diminishing returns. Such logic led AOL to issue a directive via PowerPoint, that reads like a time-motion consultant’s fever dream: “The AOL Way: Content, Product, Media Engineering, and Revenue Management.”25 AOL floundered, amid much scorn, and finally acquired Huffington Post in 2011 for $315 million. Yet it, like all media organizations, still struggles with the logic of the free-content model.

The free model has been made to work financially, to varying degrees, at sites native to the Web, including Huffington Post, Business Insider, the gossip blog Gawker, and Buzzfeed, which mixes in hard news and an occasional long-form story with unapologetic click-bait designed to be shared on social media (“Breaking: Justin Bieber Might Finally Be Rejecting Harem Pants.”)26 They are even capable of producing, on occasion, great stories. A Huffington Post series on the lives of severely wounded veterans won a Pulitzer Prize in 2012. For that matter, Deadspin, a Gawker subsite, exposed as a hoax the heartrending story of a star Notre Dame linebacker, who claimed that his girlfriend had died tragically in a car wreck. Much credit for exposing cyclist Lance Armstrong’s now-admitted blood-doping goes to the cycling blog NY Velocity, which, among other things, published a 13,000-word interview that included damning findings from an Australian physiologist who helped develop doping tests.27 But these stories are the exception that proves the click-bait rule. Laudable as they might be, they come not as a result of the free-ad model but in spite of it. Further, these operations are, after all, startups. They start small and, for the most part, they will stay small, with few if any ever exceeding the staffing levels of a single medium-sized regional daily in newspapers’ heyday.

And what offers promise and opportunity for new, digitally native news organizations turns out to be wildly inappropriate for their already established “industrial-era” counterparts. Indeed, the free model took an enormous toll across the newspaper industry. A few resisted the trend, principally the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times. After following evangelizing digital theorists and consultants for more than a decade, the newspaper industry, finally, almost universally realized its error and, led by the New York Times Company in 2011, reversed itself and began to put up paywalls that allow limited access for free and charge for unlimited access. The program was a resounding success for the New York Times and is on its way to becoming standard around the industry. Digital subscriptions, broadly speaking, have added a new revenue stream with small losses to traffic and minimal losses to digital advertising. Plus, it creates a far more intimate relationship with readers that can be valuable to boost ad rates. Among English-language papers, the Guardian is the most prominent to continue to resist digital subscriptions—and it is on an ominous track financially. As the media analyst Ken Doctor lamented in 2012, “Why didn’t we think of this earlier, before the carnage of cuts overwhelmed the profession?”28

To be clear: no one should underestimate the digital revolution in the news. The shifts are tectonic, transformative, and permanent. The relationship between readers and the news is forever altered. The shrinking of traditional news institutions has slowed but not stopped. With publishing no longer an industry but, as Clay Shirky has written, “a button,” amateur-citizens increasingly find themselves in journalistic roles, particularly in breaking-news situations: the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of 2011, the Arab Spring, and even the assassination of Osama Bin Laden, first reported on Twitter by Sohaib Athar (Twitter name @reallyvirtual).29 Crowds have proved immensely useful in sorting through large publicly posted data sets, as in the investigative site ProPublica’s Dollars for Docs project, which enabled readers to sort through more than two million records documenting the flow of $2 billion from the pharmaceuticals industry to prescribing doctors. The limits of crowd-sourcing were reached during the Boston Marathon bombings of April 2013 when users of Reddit, a message board in which participants’ votes determine an item’s prominence, falsely identified innocent bystanders as suspects in a frenzy of anonymous speculation. Mangers of Reddit later apologized. Even so, as has been observed, the traditional self-conception of news organizations has been that of producer at one end of a pipeline, with the public at the other end.30 Today that metaphor no longer holds, if it was ever accurate. News organizations will play the role of nodes on a network, a natural enough role.

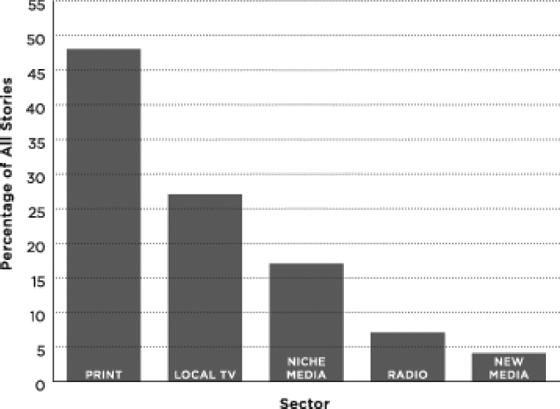

But they are and will continue to be very, very big nodes. It’s important to remember that the public, to an overwhelming degree, still gets news from traditional media. Certainly, readership of printed newspapers is declining rapidly, and the use of digital platforms is rising even more rapidly. Even so, seven in ten Americans said they got news the previous day from traditional media: watching TV, reading a print paper, or listening to the radio.31 As for Twitter, a near-obsession among news professionals, a mere 3 percent of respondents said they got news on the social media site the day before, only 7 percent of young people 18–29, and only 11 percent of the public said they had ever seen news on Twitter. And while it is true that 39 percent reported getting news the day before from digital sources, and 19 percent from social networks, figures that rise to 45 and 32 percent among the young, those figures only speak to the platform on which the news is viewed, not who actually reported it. For that, one turns to a 2010 Pew study of the Baltimore news ecosystem, one of the few of its kind, which traced where “new information” actually originated for six important local stories across subject areas (a police shootout, the governor announcing budget cuts, the closing of a local theater, etc.). The answer was the (hobbled) Baltimore Sun, other newspapers, local TV stations, and other “traditional” sources, while new media pitched in a fraction of the reporting. The findings are illustrated in figure 10.1.

The basic thrust of Pew’s findings was reaffirmed by C. W. Anderson in a study of Philadelphia’s fragile news environment published in 2013. Anderson found that, despite the best hopes of peer-production advocates, the informal news networks that have emerged in recent years did not do so spontaneously but rather came into being only with the support of institutions, mostly charitable foundations. The main fact gatherers, by a wide margin, remain the legacy news organizations, such as they are.32

FIGURE 10.1 Who reported new information: Six key storylines

This is only to say that what appears to be an increasingly lively and abundant news environment actually rests on—and masks—a shrinking fact-gathering infrastructure. And it is traditional media, ultimately, on which the vast majority of people rely. The issue is not whether experimentation with new technologies is good and necessary. All agree that it is. The problem is not trying to connect to, open dialogue with, or provide a platform for individual members of the public, which is valuable. The issue is not even the changes in attitude brought to news organizations, which sometimes seem to have placed news organizations in a prostrate posture in relation to the public and downgraded the reporters’ status to the point of allowing visitors to interrupt them at their desks at random. The real issue is—whatever the medium and whoever performs the actual work, professional journalists or someone wandering in from the newsroom café—to what extent does this model produce original, agenda-setting stories that clarify public understanding of complex problems? And here we find the great weakness in the digital-first approach. It is, as it were, the hole in FON theory. It can’t support the thing that matters most.

“The story is the thing,” McClure would repeat often to his brilliant staff. It is the thing, the main thing that journalism does. Public-interest journalism is its core, around which the rest of journalism is organized. It’s the rationale for all of it—the printing presses, the trucks, the ad departments, the journalism schools. It doesn’t much matter that McClure’s basically flamed out two years after Tarbell’s Standard Oil series. What matters is that the kind of stories it pioneered are still being produced to this day.

In this book, I’ve spent plenty of time criticizing institutional media for their failure to do the basics—what journalism was able to do in 1903 it could not muster in 2003. And that’s tragic. But institutions—flawed as they are—have proven over a century to be the best, most potent vehicle for accountability reporting. They deliver the support, expertise, infrastructure, symbolic capital, and, still, mass audience that makes for journalism at its most powerful. My concern is not with news institutions for their own sake, nor even with the well-being of professional journalism, as much as I value it. The point, in the end, is the need for agenda-setting stories that explain complex problems to a mass audience. These are the stories produced by Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Steffens, Ray Stannard Baker, Barney Kilgore, Robert W. Greene, Don Bolles, Susan Faludi, Seymour Hersh, Jane Mayer, Tony Horwitz, Alex Kotlowitz, James B. Stewart, Diana Henriques, Lowell Bergman, Donald Barlett, James B. Steele, Gretchen Morgenson, Mark Pittman, Michael Hudson, and countless others that belong to the same line of authority that made American journalism distinct and uniquely potent.

Institutionalized, professional journalism is certainly flawed, but then the question arises, compared to what?

As I write this in early 2013, some new new thinking is already underway. Journalism is experimenting with various ways of asking readers to pay a greater share of the cost of news. Further, a lot of free-floating anti-institutional talk has started to recede as the public for a while was faced with the actual prospect—not just idle chatter or, in Murdoch’s case, malign jokes—of a world without the New York Times. Clay Shirky coauthored a significant report with Emily Bell and C. W. Anderson that, while certainly affirming journalism’s entry into a “post-industrial” age and calling for a massive rethinking of the field, also reaffirmed the importance of journalism institutions and, significantly, accountability reporting by a dedicated professional cadre. “What is of great moment is reporting on important and true stories that can change society,” the authors say. Indeed. The trouble is that, as noted and as the authors themselves acknowledge, the very architecture of the Internet militates against such work.33

As we open a new era of digital journalism, it has been unnerving to witness how the Internet’s strengths—precise quantity and popularity metrics, a limitless news hole, a 24/7 publishing schedule—have meshed with corporatist preferences with an uncanny exactness. Each, for similar reasons, views long-form investigative reporting not as an asset but a problem. Yet digital-first ideas continue to spread. In May 2012, media giant Advance Publications, closely held by the Newhouse family, announced sweeping changes to the venerable New Orleans Times-Picayune, a newspaper with one of the highest readership levels in the United States and one that had done its share of accountability reporting over years, including a five-part series in 2002 that tried to call attention to the flawed levees around the city that three years later did, indeed, fail.34

Advance, which also owns Vanity Fair publisher Condé Nast and other media properties, including Reddit (see http://www.advance.net/), said the paper and its website, NOLA.com, would be reconstituted into a new company, the NOLA Media Group, as a way of adapting to the new methods of news delivery and consumption in an increasingly digital age. In press releases and front-page editorials, the company and its executives cast the moves as bold and necessary, if painful, adaptations to new digital realities. Among the changes would be a reduction in the production of printed newspapers from seven days a week to three, but the company said it would also “significantly increase its online-news gathering efforts 24 hours a day.” Incoming publisher Ricky Mathews said the changes were necessitated by revolutionary upheaval in the newspaper industry. “These changes made it essential for the news-gathering operation to evolve and become digitally focused, while continuing to maintain a strong team of professional journalists who have a command of the New Orleans metro area.”35

Unmentioned in the story or in Mathews’s subsequent 1,800 word column the next month was the fact that the “digital focus” would also entail laying off nearly half the Times-Picayune’s news staff, lowering headcount from 173 journalists to 89. The paper said 40 new people would be added back, presumably at lower wages and with less experience, leaving roughly 135 reporters, many of them covering entertainment and sports, who would be expected to produce more copy. There would also be a few “community-engagement specialists,” a quasi-marketing position. The paper hired a “Staff Performance Measurement and Development Specialist” and issued story quotas, which were later, after protests, revised to “goals.” As the paper itself said: “When the NOLA Media Group launches this fall, we plan to produce more content for our print readers and online users than ever before.”36

Newhouse made similar, drastic moves at its Alabama properties, where it cut nearly 400 reporters, including 60 percent of the editorial staff at the Birmingham News and Press-Register, leaving 47 from a staff of 112, and 70 percent of the staff of the Mobile Advertiser, leaving 20 staffers were there once were 70. In place of edited and reported papers—none of them perfect but all with substantial public-service-reporting accomplishments to their credit—Advance substituted websites that would offer, it is fair to say, a degraded product that no amount of digital rhetoric could disguise.

Even on its own terms of profit-and-loss, the business case for the free-online plan was puzzling. Taking into account losses in circulation and print ad revenue that will attend the reduction in print distribution, media analyst Rick Edmonds wrote, “The disgruntled staff and readers of The Times-Picayune are getting it right. The move only makes financial sense as the occasion for dumping many well-paid veterans and drastically slashing news investment.”37 Ryan Chittum in the Columbia Journalism Review said a closer look at the numbers suggested the plan, rather than aiming toward growth, was a way to squeeze profits from the print operation while riding its decline toward an “orderly liquidation” of the entire enterprise. The profits from such an exercise, the analysis showed, would exceed proceeds from any sale. And while Advance is free to take this particular option, most of the rest of the industry is taking an alternative path, one in which they seek to sustain quality enough to justify a paywall while using paywall revenues to help sustain quality, all while the industry as a whole navigates a transition that is still in its early stages.

No one should be under the illusion that the Nola.com path is the only one available, at all inevitable, or, least of all, in any way desirable from the public’s point of view. While community leaders and regular readers expressed outrage with the Advance plan, it received intellectual support from John Paton, CEO of Digital First, the New Haven, Connecticut–based newspaper chain owned by the hedge fund Alden Global Capital. Paton wrote a blog post that said Advance, albeit clumsily, was simply facing up to difficult realities that others were unwilling to acknowledge. Caustically, Paton wrote:

Imagine the owners’ surprise when they are lambasted for not continuing with the old line of business that is driving them out of business.

Imagine their surprise when community leaders—politicians, musicians, restaurant owners—demand the owners sell their business to them (for a song surely, it’s a dying business after all) because they want to stick with the old dying business.

Imagine their surprise when their industry colleagues and critics lambaste them for changing when change is what is needed.

As for me, the owners are doing what they think right. …

Importantly, they remain committed to their core business and mission with what resources they have.

So I support them because their industry is my industry and it will not survive without dramatic, difficult and bloody change.

And like them I am willing to do what it takes to make our businesses survive.

On Twitter, Jeff Jarvis, the journalism academic and consultant, wrote: “I agree: (Disclosure: I have a relationship w/both).”38 Thus, in a tweet, does the future-of-news intelligentsia unite behind corporate profit seeking to crush a long-standing news institution. Advance also owns, among other papers, the Cleveland Plain-Dealer, the Portland Oregonian, and the Newark Star-Ledger.

As we dig out from a collapsed financial system and the chronic political and social crises it caused, we are at the same time faced with the task of rebuilding a tradition of investigative reporting. This tradition, after all, is the way we, the nonexperts, understand complex social problems, such as the financial system. Understandably, everyone wants to know what the news will look like, how will it be gathered and presented, by whom, and who will pay for it. Will journalism ever manage to become, in the words of CJR’s founding editor, Jim Boylan, in 1961, “a match for the complications of our age”? Many people will offer solutions—business models, tools, and plans to rethink the gathering and distribution of the news. Some of the best minds in the media business, journalism, and the academy are hard at work on the problem. The time of uncertainty and financial free fall has also brought out the opportunists, but journalism has always had plenty of those hanging around.

One thing to watch out for, in my view, is the problem of “false realism”—no-can-do-ism, so to speak. That view will come from corporatists, who will assert that public-interest journalism is an affectation of self-important reporters and not economically feasible. And it will come from digital consultants who will disparage things—reporting, writing—that are not technologically determined. Both sides will seek to justify the “difficult” and “bloody” sacrifices—staff, investigations, long-form writing—that are necessary in this new reality.

It’s time for the public to be let in on what reporters already know: accountability reporting is the thing. So keep your eye on the stories, particularly the public-interest investigations, like the kind McClure and Tarbell pioneered and that Bernard Kilgore laid the groundwork for. Those are the ones that are the hardest to do, the riskiest, most time-consuming, most expensive, and, as a result, most vulnerable. Those are the ones that journalism—as we’ve seen during the runup to the financial crisis—sometimes goes to great lengths to avoid having to do.

Call it the Great Story theory of journalism. The Great Story is not going to save the world. Not every story—only the tiniest fraction, in fact—will be a Great Story. And not every Great Story will be all that great. But the Great Story—the one that holds power to account and explains complex problems to a mass audience, connects one segment of society to another—is, and has been for a century, the core around which the rest of American journalism culture is built. Other things are important, but this is more important.

The Great Story is also the one reliable, indispensable barometer for the health of the news, the great bullshit detector. Many people inside journalism would do and say anything—anything—to wriggle out from under the obligation to do the Great Story because of the risks, expense, and difficulty. It’s too long. It’s too boring. No one cares. It’s elitist, it’s patronizing, it’s self-indulgent. It’s something that might have been good once but isn’t anymore. It’s the past, not the future. Don’t be fooled. If you want to know about something important—from police corruption to the financial crisis—chances are someone will probably have to go out and investigate it. If you want to explain complex subjects to a mass audience—not just to people already in the know—the best way is probably going to be in a story form, from the beginning. And if it’s complicated, as many things are, you’re probably going to need some space.

Was Mike Hudson the perfect reporter during the mortgage era? No. Was he the only reporter during the mortgage era? No. But he was a muckraking reporter during the mortgage era: a fact-intensive, anticorruption storyteller who listened to outsiders, checked out what they had to say, and, in the face of vehement opposition from the subjects of his reporting, held power to account. And he got the story that an entire journalism subculture—business news—did not.

Could journalism have prevented the financial crisis? I report; you decide. It policed, to some degree, Fleet, FAMCO, Associates/Citigroup, and Household Finance, and it exposed Ameriquest. And as Christopher Peterson’s 2007 Cardozo Law Review article observed, public exposure was kryptonite to powerful predatory lenders everywhere. A single story—the New York Times/ABC News exposé of Lehman Brothers’s ties to predatory lending, had all of Wall Street running for cover.

If someone tells you this kind of reporting is not possible anymore, don’t believe it. And if someone tells you that the Great Story isn’t important, tell him that you read somewhere that that’s not true, either.

The models that can produce the Great Story, along with the other wonderful things available to journalism today, are the models to keep. If that happens to be NOLA.com, more power to it. If digital advertising alone—with no paywalls—can pay for it, fabulous. But don’t count on it. The models that can’t support the Great Story—Digital First, for one—are to be deemed destructive if they are applied to existing news institutions, irrelevant if they aren’t.

I say nothing here that reporters and editors don’t already know.

What supports the Great Story is what we need. Everything follows from there.