Chapter 9

MUTUALISM AND THE ART OF ROAD CYCLE RACING

I CAME RATHER LATE to road cycle racing. Generally I am not fussy in my sporting interests. Tennis, soccer, rugby, cricket, baseball, golf, basketball, American football, sailing, squash, Australian rugby league… the list is long. But I drew the line at cycling. It looked like a tedious trial of strength, and I attributed its fanatical support in Europe to a Latin predilection for machismo over sporting subtlety.

But I couldn’t have been more wrong. It was the 2012 Olympics that woke me from my dogmatic slumbers. There was a great deal of interest in the road cycling in Britain, because for once the men’s team had a real chance of gold. Bradley Wiggins had just become the first Briton to win the Tour de France, and the team also contained legendary sprinter Mark Cavendish and future Tour de France winner Chris Froome.

But in the event, the men’s team flopped. I didn’t manage to watch the race, but the newspapers afterwards said that the British failed to win gold because the Australians and Germans didn’t help us enough—which somehow seemed simultaneously puzzling and unsurprising.

Still, all the brouhaha had piqued my interest, and the next day I caught the second half of the women’s road race. As it unwound I became transfixed. With about 40 of the 140 kilometres left to go, a group of four women from different countries broke away from the pack, and promptly proceeded to operate as a team, taking turns at the front to shield the others from the wind.

At first this made no sense to me. I knew that wind resistance is a crucial factor in cycling, and that road racing involves teams who share the load of pushing through it, going to the front in turn in order to let the ones behind “draft” and conserve their energy. But I was watching four women with no common interest working together. An Englishwoman, a Dutchwoman, an American, and a Russian. More like the beginning of a joke than a natural collective. What were they doing collaborating?

But they clearly were, so with the help of the commentators and some cycling friends I started to figure it out. The rationale for breakaways in a road race is to stop the sprinters like Mark Cavendish winning. If the whole pack—the “peloton”—arrives at the finish in a bunch, then some squat figure with thighs like an elephant will shoot through and grab the gold. So the taller, more wiry cyclists need to leave the sprinters behind. Plan A for most teams is to shepherd their pet sprinters around the course and release them at the end. But if your sprinter starts lagging, or if you don’t have a good one to start with, then plan B is for the wiry types to strike out and leave the sprinters behind.

That’s what I was watching. Four skinny ones who were unlikely to win in a mass finish but who had a good chance of a medal if they could keep ahead of the pack. So for the moment they were working together. On their own they would quickly get exhausted, so to stay ahead of the peloton they were taking turns. Each helped the others for a while, shielding them from the wind while they got their breath back.

Philosophers, along with economists and biologists, spend a lot of time worrying about cooperative behaviour. Standard assumptions about economic rationality and biological evolution imply that humans are natural competitors, not collaborators. Still, there on the television was direct proof that even sporting rivals will sometimes work together.

It occurred to me that the cyclists might have something to teach the theorists. I couldn’t have been more right. The deeper I went into the tactics of road cycle racing, the more lessons I discovered for the logic of rational action. As we shall see in the course of this chapter and the next, cycle racing provides an unparalleled resource for anybody who wants to understand the interplay of individual and collective motives in human life.

Let us start with the traditional “puzzle of altruism”. Why do people, and many animals, do things that benefit others more than themselves? Why do they pay their share, wait their turn, and generally do their bit? This can seem illogical: if everybody else is going to be public-spirited, I’ll be better off quietly stealing a march; and if the others aren’t going to be public-spirited, I’ll be wasting my time being nice. So either way, what’s in it for me to be unselfish? (“But suppose everyone felt that way”, Yossarian is asked in Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. “Then”, said Yossarian, “I’d certainly be a damned fool to feel any other way, wouldn’t I?”)

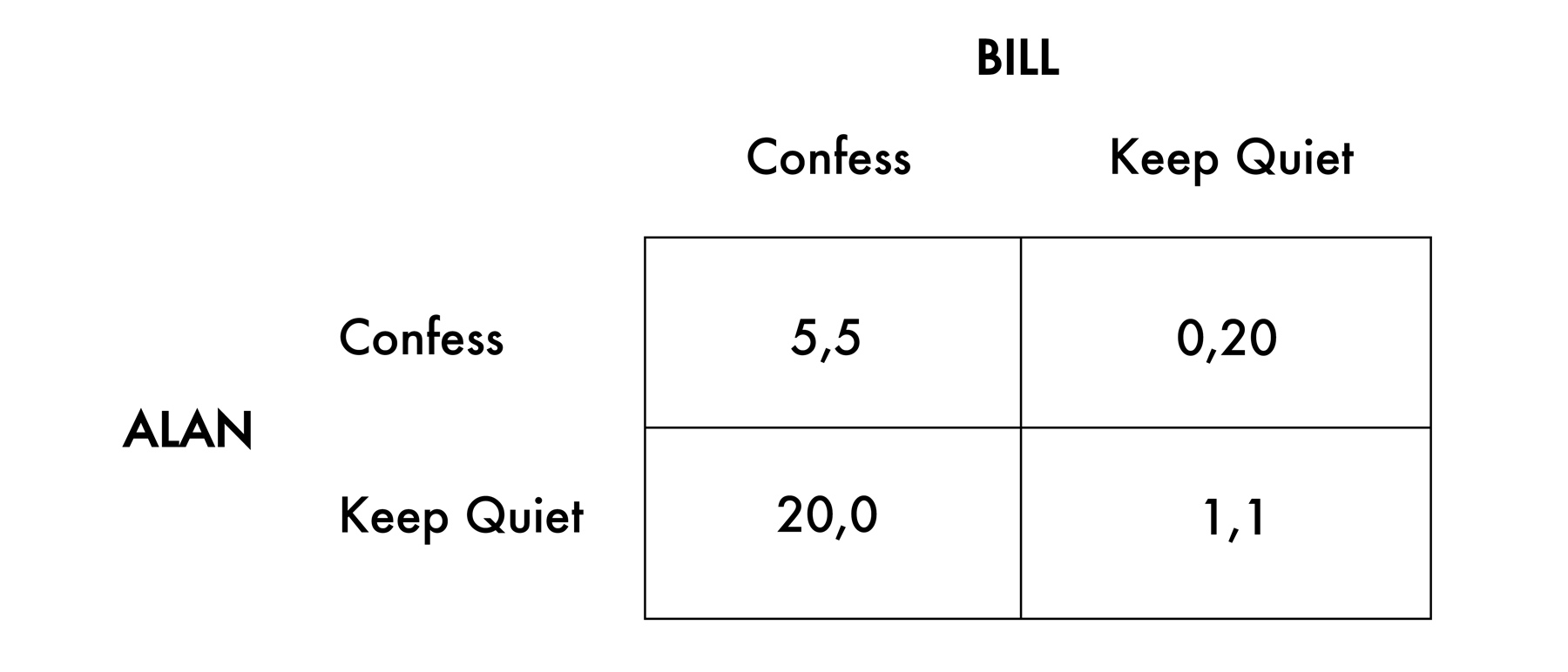

This puzzle about altruism is often illustrated by the “prisoner’s dilemma”. Imagine Alan and Bill have been picked up by the police after a burglary. The cops aren’t sure they have the right men, so they put them in separate cells and offer them both the same deal. “If you turn state’s witness, and the other guy refuses to cooperate, we’ll put him away for twenty years and you can go home right now. But you’d better hope that he doesn’t also confess, as then we won’t need your evidence, and we’ll lock you both up for five years. And in the unlikely event that you both manage to keep quiet, we’ll keep grilling you for a year, but then, damn it, we’ll have to let you both go.”

We can summarize this with a “pay-off matrix”. The rows represent Alan’s two choices, the columns represent Bill’s, and the two numbers in each box signify the years that Alan and Bill will respectively spend in the clink for each pair of choices.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

It’s a nasty setup. If Alan is looking after number one, he’ll reason as follows. “Perhaps Bill will confess. If so, I’d better confess too, as I don’t want to be the mug who gets twenty years while he gets off scot free. On the other hand, maybe he won’t confess. But then it will also suit me to confess, as I can avoid a year’s unpleasantness and go straight home to my ever-loving family.” Either way Alan’s self-interest argues for confessing. And if Bill is like Alan, he will reason just the same. So two selfish burglars will both confess—with the result that they will get five years each, when they could have both gone home after one year, if only they had both kept their mouths shut.

This is why theorists are puzzled by public-spirited behaviour. Even in cases where everyone can see that it would be best to pull together, the logic of rational choice pushes us apart. There seems no reason not to “free ride” by hopping the turnstile and leaving it to others to pay the fares that will keep the trains running. But then everybody does the same, and the train company goes out of business, and we are all worse off.

In real life of course, there are normally extra constraints to stop this from happening. The ticket inspector enforces the rule that passengers must have a ticket, and fines anyone caught without one. Alternatively, enough travellers have “internalized” the norm about tickets, and simply feel that it would be morally wrong not to pay. (When C. E. M. Joad, the national celebrity and inventor of “gamesmanship” from Chapter 6, was found without a ticket on the London-Exeter train, the public reaction wasn’t just that he was a fool for being caught. Far worse, in most people’s eyes, he was also exposed as a moral knave for cheating the railway company.)

Still, in many cases there must be a simpler explanation for cooperation than the pressure of official or moral sanctions. Think of the Olympic cyclists. They’re not subject to any norms requiring them to support a joint enterprise. If anything, it’s the opposite. They’re supposed to be competing, not collaborating.

A crucial factor here is the small number of cyclists. Here’s a comparable case. Suppose that there are half-a-dozen of us in our office. Our planned Christmas outing needs at least four to chip in, otherwise it’s off. Contributions are made privately, to spare the less well-off embarrassment. I know I’ll enjoy it a lot, and I can afford it, so I cough up. Nothing puzzling there. But note that my behaviour is already a kind of altruism, in that I alone bear the cost of my contribution, but all will share the benefit of the outing if it now goes ahead.

The key factor in my decision is that my contribution might easily tip the balance. In a big office with hundreds of people, there’s no real chance that my failing to pay up will kibosh the outing, and so no economic motive for me to chip in. But when the numbers are smaller, it is all too likely that my money will matter.

Small-scale cooperation like this is common. People pick up litter in their own street, they organize stalls at the school fair, they take their turn driving for the car pool. The familiar economists’ question is—why do they exert themselves in this way, if they can see that their contribution will be pointless? But in small-scale cases like these, the question is often misplaced. When it comes to street litter, school fairs, car pools and office outings, their individual contribution may be far from pointless, but the crucial difference between success and failure.

And this was just the kind of set-up I was watching in the women’s road race. Each rider had an interest in doing her time at the front, even though this hurt them and helped the others, because, if they didn’t, it would kibosh the whole breakaway. It takes a lot out of you doing a spell at the front. You use about 50 percent more energy that those you are pulling along. If a slacker left it to the other three in the group to take turns, then those doing the work would tire more quickly, the breakaway would lose momentum, and the bunch behind would reel them all in.

A better model for small-scale cooperation is the “stag hunt”, not the prisoner’s dilemma. Here Alan and Bill are hunters, not burglars, and their choices are whether to hunt a stag (worth five days of food each) or a rabbit (just one day’s food). There are plenty of stags around, but catching them is a two-man job, while a single man can always bag a cottontail. So if Alan leaves home with his stag-catching gear, but Bill opts for a sure rabbit, then Alan will end up empty-handed.

The Stag Hunt

Now the reasoning comes out differently. It’s no longer true that Alan is better off chasing a rabbit, whatever Bill does. True, it will suit him to chase a rabbit if Bill chases one, as hunting for stag on his own will ensure he ends up empty-handed. But, on the other hand, if Bill does leave home ready to hunt a stag, then it will be very much in Alan’s interests to do likewise. So, provided that Alan thinks there’s a reasonable chance of Bill setting out to hunt for stag, it will be rational for him to follow suit. And since Bill can figure things out similarly, they’re likely both to end up happily feasting on venison.

Note how opting to hunt stag means that Alan is putting himself out, foregoing his sure rabbit, and making a choice that benefits Bill as much as himself. The same applies when I go out of my way to pick up litter in my street, or organize a school fair stall, or contribute to the staff outing. I make an effort, and others benefit. Still, the reason I’m so helping the others is clear enough. I too will suffer if my non-cooperation means a rabbit rather than a stag, or an ugly streetscape, or a dud fair, or no outing.

You might wonder whether these cases should count as real altruism. After all, everybody involved is serving their own interests. While they may be benefitting their colleagues even more, they aren’t going so far as to choose an option that positively works against their own welfare.

Theorists distinguish between “weak” and “strong” altruism. Weak altruism is when your colleagues also reap the benefits of a choice that benefits you. What is good for you is also good for the group. Strong altruism is when your choices positively leave you worse off.

To avoid confusion, I shall use the term “mutualism” for weak altruism from now on. Weak altruists are like a mutual benefit society. They pull together because it is in their individual interests to do so. The cyclists and the stag hunters aren’t being strongly altruistic. While their contributions help the others, they also help themselves. By chipping in you make it more likely that the breakaway will succeed, or that a stag will be caught, things that are very much in your personal interests.

With strong altruism, by contrast, there is no personal pay-off. I help a little old lady across the road. I give money to Oxfam. These actions help the old lady and developing countries, but bring me no obvious gain.

Mutualism may be enough for stag hunts, but we need strong altruism to get out of the prisoner’s dilemma. Enlightened self-interest can do the trick in stag hunts, precisely because each hunter’s self-interest is best served if they both cooperate. But in the prisoner’s dilemma, each prisoner’s self-interest is best served by non-cooperation, whatever the other does.

Because of this, the prisoner’s dilemma is only solvable if Alan and Bill are good enough friends to care about what happens to the other, even if it costs them something themselves. If they are both prepared to forego immediate release, because that would cost their mate twenty years inside, they should manage to end up with only a year in jail each. And, more generally, strong altruism will lead people to support social enterprises even when it would be cheaper for them not to.

Some cynical people doubt whether anybody is ever altruistic. (We can drop the “strong” now, since we’re using “mutualism” for the weak version.) In the end, the cynics insist, everybody is looking out for number one. Aren’t our actions inevitably guided by our own desires? So doesn’t it follow that our choices will inevitably be designed to further our own interests?

No. While altruism does face serious challenges, it can’t be ruled out that quickly. Of course everybody’s actions are triggered by their own desires, rather than anybody’s else’s. That’s not the issue. The interesting question is what their desires are aimed at. Most people will no doubt have some desires for their own health and welfare. But that’s consistent with also desiring good things for others. Nothing in logic rules out desires that are aimed at benefitting other people. And a desire that is so aimed at someone else’s benefit, without any associated pay-off for the agent, will be a genuinely altruistic desire all right.

Still, even if altruism can’t be ruled out by logic, perhaps it is ruled out by psychology. Am I really sure that I am motivated by the welfare of the little old lady, or the starving millions in Africa? Perhaps my real aim is to win approval for myself, or maybe to enjoy the warm glow I experience when I see how I have benefitted others.

But this cynical scepticism about altruism is hard to maintain. What about the terminally ill mother who makes arrangements for her children after she is dead? Or the soldier who throws himself on a hand grenade to save his comrades? They can scarcely be aiming for the warm satisfaction of seeing others benefit, given that they won’t be around to observe the results of their actions.

Perhaps the cynics can appeal to the warm glow that arrives once you know you’ve done the right thing, even if you never see the pay-off. Still, by this stage the cynicism is starting to look forced. What’s wrong with the idea that the mother simply wants to benefit her children, or the soldier his comrades? Why keep seeking some self-serving meaning for what look like straightforwardly altruistic choices?

Well, if the cynics were simply mean-spirited misanthropes, then they probably wouldn’t be worth taking seriously. However, they can also bolster their cynicism with a serious theoretical argument. This appeals to biological evolution. Natural selection favours animals that favour themselves. This raises real questions about the idea of evolved beings favouring others at their own expense.

We need to go a bit more slowly here. Natural selection is about genes. So far we have been talking about desires. They’re not the same thing. Our desires are influenced by our environments and our culture, as well as by our genes. So it would be too quick to rule out altruistic desires simply on the grounds that natural selection works against altruistic genes. Perhaps it is our cultural training that induces us to be altruistic, even if our genes don’t.

Still, the evolutionary argument can’t be dismissed that easily. Our desires aren’t completely independent of our genes. Apart from anything else, our tendency to acquire desires from our cultural surroundings is itself a product of natural selection. So, if altruistic feelings were an evolutionary no-no, we might expect our biological nature somehow to veto them.

Some of you might be wondering why natural selection should be in tension with altruism in the first place. Doesn’t biological evolution favour things that are for the good of the species? And won’t cooperation among animals help to preserve the species? From this perspective, you’d think that altruism among animals would be the biological norm.

However, for better or worse, evolution doesn’t work like that. When I was a twelve-year-old, I hugely enjoyed one of the first nature films, Disney’s White Wilderness. In one famous scene, we saw a swathe of Norwegian lemmings purportedly responding to an overpopulation crisis by throwing themselves off an Arctic cliff. According to the sonorous voice-over, this was to ensure that the remaining lemmings would have enough resources to flourish and preserve the species.

Even at a young age, I found this puzzling. (Let’s put to one side that they were brown lemmings from Canada, not Norwegian ones, and that they didn’t jump, but were pushed by the Disney camera crew.) Suppose that there are two kinds of lemmings, those with an innate urge to jump over cliffs when it gets crowded, and those who hang back and enjoy life once the others have gone. Now, which sort would you expect to predominate after a few population crises? Lemmingkind as a whole might well do better when there are self-sacrificers around, but that doesn’t alter the fact that the selfish ones will leave more descendants, simply because their altruistic cousins have so helpfully eliminated themselves from the scene.

The lemmings show why natural selection generally works against altruism. Biological evolution doesn’t favour characteristics that are good for the species, but those that help individual animals to have more children than their conspecifics. If you favour others in the species at your own expense, you’re simply helping them to get ahead in the breeding competition.

Still, whatever biological theory says, it certainly looks as if there is plenty of altruism in the animal world. Meerkats act as sentinels, literally sticking their necks out to watch for predators; vampire bats share harvested blood with comrades who have come home hungry; worker bees disembowel themselves when they sting intruders to their hive.

Over the past fifty years evolutionary biologists have pondered this conundrum long and hard. The consensus nowadays is that we shouldn’t be too quick to rule out biological altruism. The Disney scriptwriters might have got into a muddle about lemmings. But, under special conditions, it is perfectly possible for altruistic genes to evolve.

The key requirement is that the benefits of altruism should tend to fall on other altruists. Then the upshot of altruistic behaviour will be that other altruists will prosper and have more children, and as a result altruistic genes will spread through the population.

Think of the prisoner’s dilemma again. Altruistic pairs of prisoners will do better than selfish pairs, both getting out after a year, rather than festering inside for five. Of course, a selfish prisoner paired with an altruist will do even better, going straight home after ratting on his partner. Still, the fact remains that, if altruists tend to be paired with other altruists, they will spend less time in jail on average than the self-servers. And, by the same coin, altruistic genes will spread faster than selfish ones, provided only that altruists tend to hang out with other altruists.

A number of different circumstances can ensure that altruists cluster together. For a start, most animals live in extended family groups. So, if there are genes that foster altruistic behaviour, they will tend to run in families, with the result that altruists will benefit from the presence of their altruistic kin. But kinship is not essential. Certain kinds of geographical segregation can have the same effect. Or perhaps altruists simply tend to seek each other out. One way or another, there seems plenty of scope for biological altruism to evolve.

In the end biology offers no support to cynical doubts about altruistic motives. Evolution leaves plenty of room for animals that benefit others at their own expense. Once we view human psychology in this light, there’s no good reason not to take apparent acts of charity and self-sacrifice at face value.

Road cycle racing is a case in point once more. It arguably offers frequent displays of genuine altruism, in addition to its episodes of self-serving mutualism. Consider the organized teams, as opposed to the temporary alliances within mutually cooperating breakaways. The domestiques, as the French bluntly term the lesser team members, slave away shepherding their team leader around the course. Their aim is to increase their leader’s chance of a medal, but in doing so they sacrifice any hope of winning prizes themselves. (Curiously, despite the essential role of teams, road cycle races don’t normally have any team prizes, only individual ones. The domestiques gain no formal recognition when their leader crosses the line first.)

A cynic might retort that there is nothing noble about the domestiques. A motley of other motives can explain their subservience, apart from a selfless desire for the team leader to win the gold. For a start, there is money. At the higher levels of road cycling, the working members of the team are paid, and well paid at that. And we can add in such incentives as the desire to enhance your cycling reputation, and perhaps to gain a future chance as a team leader.

But this doesn’t explain all the cases. Underneath the Tour de France and the other prestige events lies a huge pyramid of amateur road races. Even at the lowest levels, the cyclists voluntarily form themselves into teams. I quote from the website startbikeracing.com: “Team riders decide among themselves which has the best chance of winning. The rest of the team will devote itself to promoting its leader’s chances, taking turns into the wind for him or her,… and so on.” At the lower levels, there’s no money involved, and few competitors are concerned with any kind of cycling career. They really don’t seem to be after anything except victory for their leader.

I don’t want to go overboard on the cooperative aspects of road cycling. After all, these are races. The whole point of the exercise is competition. Who will reach the finish line first? Still, you won’t understand cycle racing until you appreciate the complex dance of altruistic, mutualistic, and selfish motives that are in play in a road race.

Let’s go back to breakaways. As in the 2012 women’s Olympic race, the logic of mutual support pushes the riders to share the load equally. But at the same time this cooperation is under constant threat from the individual aspirations of the competitors.

Each rider would prefer to conserve energy in order to maintain an edge over the others as the finish line approaches. So they’ll be inclined to hang back a bit and let the others do more work. But they can’t be too obvious about this, since the others won’t want to pull them along only to be left behind at the end. If they think that’s what’s going to happen, they’ll give the breakaway up as a bad job.

This kind of thinking might seem to imply that a breakaway will only keep rolling if all its members are equally good finishers. After all, why would you put in all that effort if you know that one of the others is sure to beat you in the finale? However, now another level of calculation enters the picture. The stronger finishers will tolerate the weaker ones making less of a contribution to the breakaway. This might level the playing field for the final dash, but the good finishers still need the others’ help to keep the breakaway going. So the stronger ones will try to gauge it right, and let the others retain a bit more energy, but not so much as to let them succeed in the final sprint.

The weaker ones will also be making similar calculations. And then there is the question of when to stop cooperating and strike out for the finish. As the line draws nearer, the danger of being overhauled by the peloton diminishes, and the need to conserve energy comes to the fore. It’s a complicated game that calls for delicate judgement on all sides.*

Of course, all these fine-grained tactics are premised on the assumption that the breakaway will stay ahead of the peloton, with its complement of squat sprinters itching for a mass finish. In truth, however, successful breakaways are very much the exception rather than the rule. One of the strangest things about cycle racing is that the peloton can nearly always catch a breakaway. According to Chapatte’s Law, named after Robert Chapatte, the doyen of French cycling journalists, the peloton needs only ten kilometres to eat up a lead of one minute.

This might seem puzzling. We’re talking about speeds of around 50 kilometres per hour, so Chapatte’s Law means that the peloton can go about 10 percent faster than a breakaway. If I didn’t know better, I wouldn’t have believed that an unwieldy mass of 100-plus cyclists, packed together on narrow roads, could so easily outrace a well-organized and determined breakaway. The peloton does have the advantage of a large pool from which to draw temporary front-runners, and so spread the energy drain more thinly. But, still, why would any member of the peloton choose to tire themselves out at the front, ceding the advantage to those who hang back?

The answer lies with altruism and mutualism once more. The basic reason the peloton can go faster is that the domestiques are ready to sacrifice themselves. If a team has no one in the breakaway up ahead, then it needs to do what it can to reel them in. So some of its members will altruistically devote themselves to bridging the gap, even if they exhaust themselves in the process.

Still, one team normally won’t want to do this on its own. There’s no point in expending all your domestiques too early, as then you won’t have any left to shepherd your sprinter through the rest of the race. A single team won’t want to use up more than two or three catching the breakaway. But now mutualism comes to the aid of the party, this time at the team level. A number of the teams in the pack will often have a common interest in catching the breakaway, so they will each sacrifice a few members to the cause, pooling resources to sustain the drive.

This too can be a matter for fine judgement. The teams in the peloton must now make the same calculations as the individuals in a successful breakaway. If one team has an outstanding sprinter, then the weaker teams won’t be so keen to tire themselves out; the strongest team will need to tolerate this to some extent, since it needs help in catching the breakaway; and so on. (It was on this tactical reef, as I understand it, that the British Olympic hopes foundered in 2012. Because Mark Cavendish was the stand-out sprinter, there was scarcely any incentive for the Australian and German teams to help Britain, and so the breakaway got away.)

A few years ago, I wouldn’t have dreamed that cycle racing was so interesting—and I have only scratched the surface so far. It becomes even more intricate when we note that the division between domestiques and leaders can be vague and fluid, and that riders in multi-stage tour races often need to choose between pursuing various different stage and overall prizes.

With all this in play, it is often hard for riders to know which way to jump when a breakaway is launched. Should they join it, or let it go, or try to sabotage it? When a rider sits at the back of a breakaway, should they tolerate this, or aim to drop the shirker, or abandon the breakaway as a bad job?

Some riders are better at these computations than others. Lance Armstrong was apparently preeminent in this field, but lesser lights are prone to blunder under the pressure of the moment. Nowadays, in the big professional races, the team managers instruct their riders on radios. It strikes me that it would be more fun without them.

In any case, cycling offers an unparalleled resource for students of human cooperation. Mutualism, altruism, allowances for those with lesser resources, choices of when to go it alone—it’s all there. Don’t be put off by the macho façade. If you want to understand the many ways in which humans manage to work together, you’ll do well to become a road cycling fan.