Chapter 10

GAME THEORY AND TEAM REASONING

IN THE LAST chapter, I talked about the altruism of road-cycling “domestiques” who sacrifice themselves for their team leader, like worker bees slaving for their queen. The idea was that they are motivated by a desire for their leader to win first prize, rather than by any promise of benefit to themselves.

As we saw, this doesn’t necessarily apply at all levels of cycle racing. Professional riders are often well paid for their pains, not to mention their ambitions to rise up the hierarchy of working cyclists. Still, neither of these factors applies at the lower amateur levels. There really doesn’t seem to be anything in it for the amateur drudges, apart from their altruistic aspirations for their leader’s victory.

Whenever I put this idea to my cycling friends, however, they invariably disagree. Oh no, they say. The domestiques aren’t being altruistic. They don’t care about their leader. They want their team to win and are simply pursuing this personal desire.

At first I suspected that my cycling friends were making the old mistake of ruling out altruism from the start, on the spurious grounds that everybody always acts on their own desires. So I explained to them that, while that’s of course true, it doesn’t decide the more interesting question of what people’s desires are aimed at. And, I continued, since the domestiques’ desires really are aimed at someone else’s benefit, namely their leader’s victory, rather than any reward for themselves, they should be counted as genuinely altruistic.

But my friends were insistent. No, they assured me, they understood the idea of altruistic desires all right. The trouble was that I didn’t understand the motivation of cycling team members. The cyclists don’t want their individual leader to benefit. They want their team to win.

On reflection, I realized that my friends had a point. I was thinking too much like an economist. I was assuming that teams are nothing more than collections of individuals. I had bought into Margaret Thatcher’s vision of the world: “There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and families.”

Teams give the lie to this individualistic vision. As we saw a couple of chapters back, they are funny things, which transcend their individual members, whatever Margaret Thatcher and the economists may think. A team can survive the loss of any individual player, indeed the loss of all its players. (Think of those long-suffering Red Sox fans, and all the years they prayed for a World Series win. If they’d been committed to a bunch of individuals rather than a team, they would never have had their prayers answered, since the athletes they originally supported had long moved on.)

So I started thinking harder about the significance of teams for theories of motivation and decision-making. I realized it isn’t easy to accommodate them in the way philosophers and economists think about choices. Indeed, the more I thought about the subject, the more it struck me that teams make deep difficulties for conventional theories of decision-making.

The insistence of my cycling friends was just the start of it. They certainly had a good point. Cyclists who care about their team are hard to place on the conventional selfish-altruistic spectrum. Precisely because the object of their concern transcends any set of individuals, they don’t fit into the normal definitions used by economists.

Behind this issue of defining altruism, however, there also lies a deeper truth. As well as being possible objects of concern for decision-makers, teams can also be decision-makers themselves. This kind of “team-reasoning” challenges the whole structure of conventional decision theory, not just its definitions. The economists don’t like it at all. But the sporting examples make an irresistible case for recognizing teams as agents that can make decisions in their own right.

Let us start with the initial definitional point about “altruism”. This arises because the Thatcherism implicit in economic theories of decision-making leaves no room for agents to care about anything but individual people. Whether agents are selfish, aiming to help themselves, or altruistic, aiming to help others, they are always concerned about individuals. As economists see it, there’s no question of caring for teams as such. After all, there are no teams, only individuals.

But what then are we to say about the domestiques who devote themselves to a team victory? Their goal is a living testimony to the way teams transcend their members. They want their team to win, not the leader to gain the winner’s medal. The leader’s prize just happens to be the symbol that cycling uses to mark which team has won. It is nothing but a historical quirk, my cycling friends assure me, that the prizes are given to individuals and not to teams. In truth, road cycling is as much a team sport as rugby or basketball.

Sometimes cyclists seem to take this logic to extremes. The road cycling races in the Olympic or Commonwealth Games, for example, have gold, silver, and bronze for the first three over the finish line, and no official recognition for teams at all. In this respect it’s like the 1,500 metres, rather than the water polo tournament.

So, if you didn’t know better, you’d think that’s what the athletes wanted. One of the medals. Gold if you can get it, but failing that silver or bronze. But you’d be mistaken. The members of each country’s team devote all their efforts to getting their leader first across the line, happy to share the glory of a team victory, even at the cost of a medal.

I watched a striking example of this in the Commonwealth Games women’s road race in 2014. One of the England riders, Emma Pooley, broke away from the leading bunch with some 30 kilometres left to go. The idea was to make the opposition chase her, so they’d be out of puff when the England leader Liz Armistead made her bid for gold. And so it went. But what puzzled me, in my ignorance, was why Armistead didn’t help Pooley when she passed her with 7 kilometres left and they were a minute ahead of the rest. Armistead was safe for the gold, and could have made sure that the now-tiring Pooley won the silver, by forming a temporary alliance of two and helping her push through the wind.

I was tweeting my puzzlement at the time. Richard Williams, former chief sports writer of the Guardian, and himself a keen cyclist, posted a reply: “Now that would be, as they say these days, a big ask. The team rides for the leader: the leader’s responsibility is to win.” This struck me as oddly harsh, given that Games medals were at stake. But it makes good sense once you realize that, from the riders’ point of view, all that matters are the teams, not their individual members. (Happily, Pooley did hang on for the silver—but no thanks to her teammate.)

Our current concern is with the definition of altruism. Does wanting your team to win count as altruistic? The normal definitions of altruism are stymied by this question, precisely because they take it for granted that the objects of desires are always individual people. If you are aiming to benefit yourself, then you are selfish, and if you are aiming to benefit someone else, then you are altruistic. This doesn’t say anything about where you stand if you’re aiming to benefit a team.

I’m not entirely sure what we should say here. On the one hand, there is something selfish about team aspirations. To the extent that you identify with the team, you yourself will share in its success. But, by the same coin, since others are equally involved, you are aiming at their success too, and so to that extent you are thinking altruistically.

I don’t think it matters too much which way we go. If the normal economists’ distinction between selfish and altruistic desires fail to deal with all the cases, that’s scarcely our problem. It just shows that people care about more things than are dreamt of in economic theory. Perhaps we should stretch the definition of “altruism” to cover team aspirations. Alternatively, we could introduce a third category of “collectivist” desires to cover the extra cases. As I said, it doesn’t really matter. In the end, we can stipulate as we choose. (In the rest of this chapter, I’ll take “altruism” to cover ambitions for teams.)

So one consequence of the reality of teams is that they put pressure on standard definitions of altruism. Perhaps that doesn’t seem worth writing home about. But teams also matter to decision-making in a second and far more interesting way. Once you are part of a team, you can address your problems differently. You are no longer limited to asking, “What shall I do?” Now you can ask, “What shall we do?”

In line with their Thatcherite vision of the social world, orthodox theories of rational choice think of team choices as the sum of individual choices. Each member of the team separately selects the action that promises the most of what they want (that “maximizes their expected utility,” as the economists put it). The strategy adopted by the whole team is then the sum of these individual choices.

However, there is no compelling reason for us to think of group decisions in this individualist way. Humans naturally form themselves into families, foraging parties, friends on a night out… and sports teams. And when they do, they tend to think as a group. They select that joint strategy that promises to maximize benefit to the group, and then they all play their allotted parts.

It makes a big difference. Consider the setup known in the game-theory literature as the “Footballers’ Problem”. Arsenal’s Jack Wilshere has the ball in midfield and can slide it to Olivier Giroud down either the left or right channel. Giroud’s run and Wilshere’s pass must be simultaneous. Both know the defender on the left is significantly weaker. What should they do?

Go left, of course. But surprisingly the branch of orthodox thinking that deals with coordinated actions—game theory—fails to deliver this result. This is because it starts with the choices of each agent, and the best choice for each agent depends on what the other does, and what the other does is supposed to be predicted by game theory… so orthodoxy runs into sand and fails to select left as the uniquely rational option.

But now suppose the players are thinking as a team. They have four joint options. Pass right, run left; pass left, run right; pass right, run right; pass left, run left. What should we do? It’s a no-brainer—the last option is clearly best.

This is just one example of how team reasoning can find solutions that individual game theory cannot reach. Perhaps it is worth going a bit more slowly here. To better understand why individual thinking breaks down in such cases, it will be helpful to introduce the notion of a “Nash equilibrium” (named after the Princeton mathematician and Nobel laureate John Nash, whose troubled life was portrayed by Russell Crowe in the film A Beautiful Mind). The basic reason that team reasoning often trumps individual thinking is that many problems of coordination lack a unique “Nash equilibrium”.

Let me explain. Theorists normally divide problems of rational choice into “decision theory” on the one hand and “game theory” on the other.

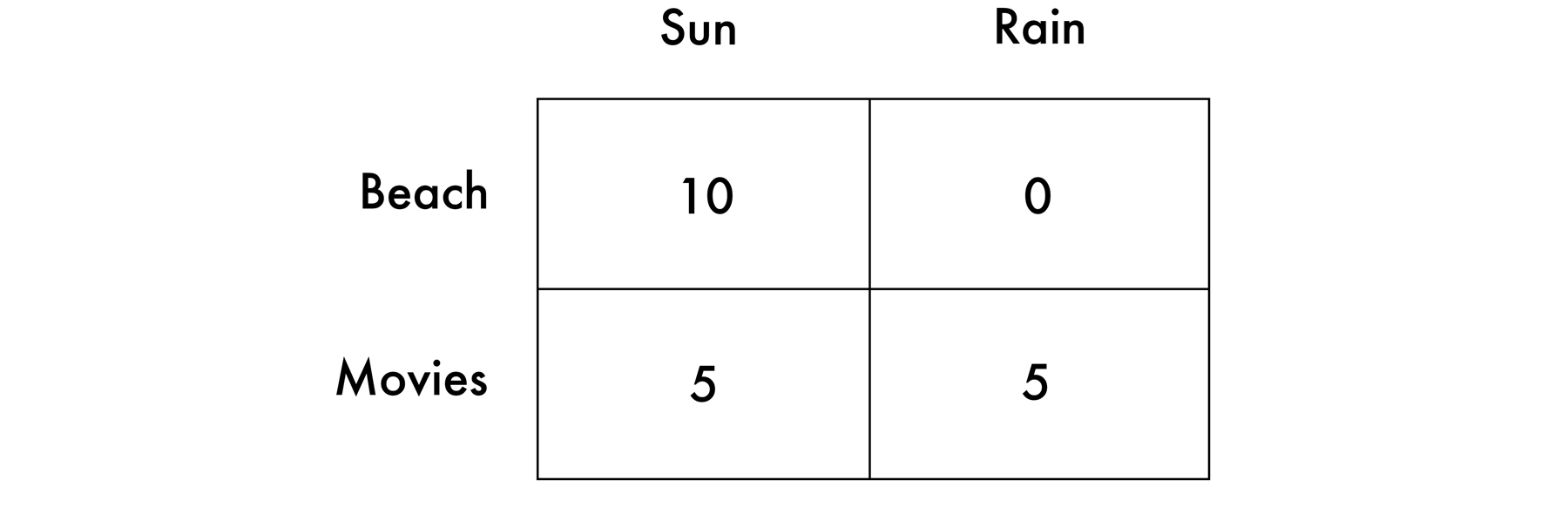

Decision theory covers cases where only one person is doing the thinking. I’m wondering whether to go to the beach or to the movies. I’ll enjoy the beach more, but only if it doesn’t rain. Let’s imagine we can measure my pleasure: 10 for the beach on a sunny day, 0 for a rainy day at the beach, 5 for the movies either way.

Beach or Movies?

According to decision theory, rationality requires me to “maximize expected utility”—that is, to choose the action whose average pay-off across sun and rain, weighted by their respective probabilities, is the greatest—which in our case will be the beach if and only if the probability of sun is over 50 percent.*

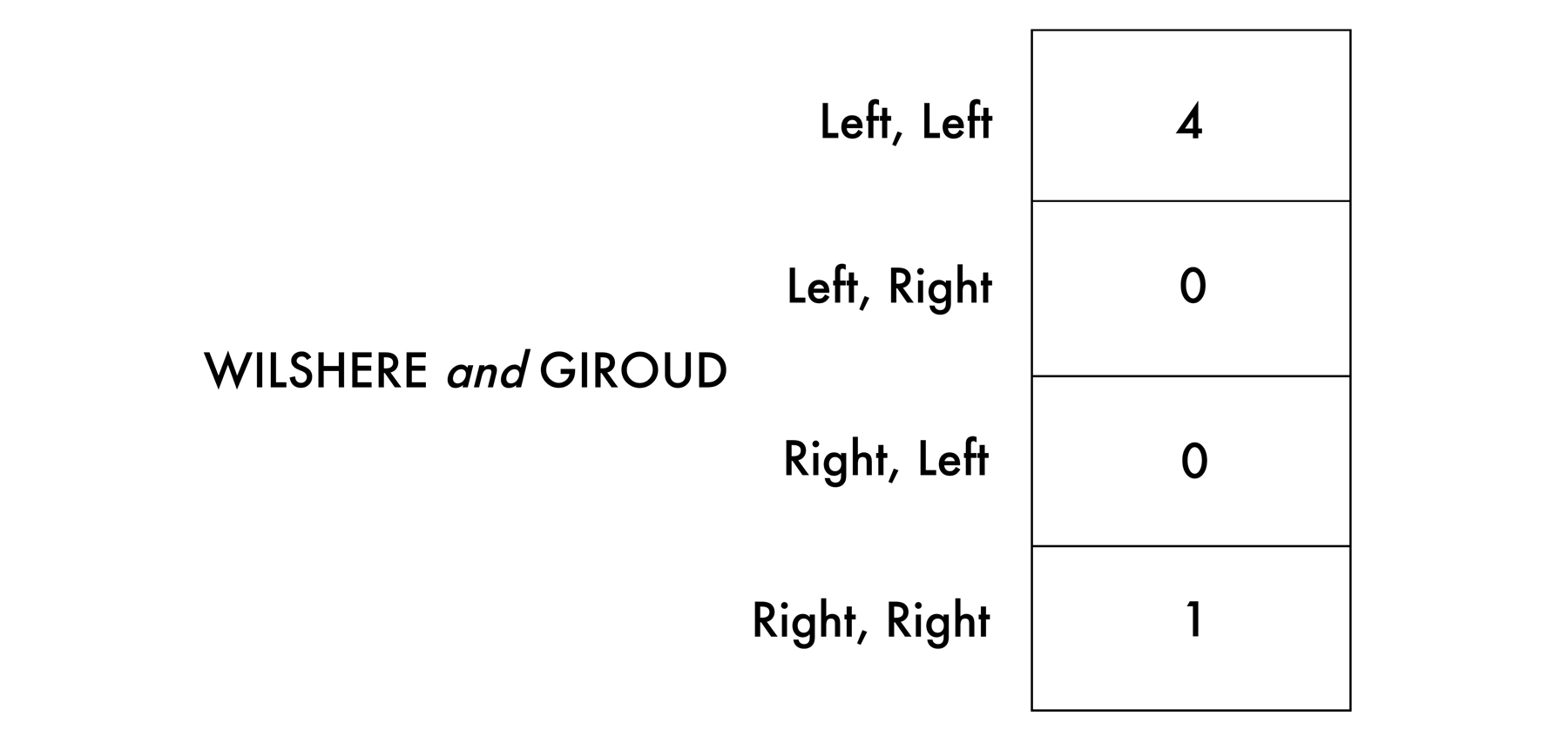

Game theory comes in when a number of people make choices simultaneously, and the pay-offs for each depend, not on natural events like the weather, but on the choices of the others. Take the Footballers’ Problem again, and suppose that the matrix (in the Footballers’ Problem: Decision Theory on the next page) represents how Wilshere’s pay-offs depend on Giroud’s choices. (It’s useless passing right if Giroud goes left, or vice versa; it’s not too bad if you pass right and he goes right; but it’s clearly best if you pass left and he goes left.)

Now, in principle Wilshere could adopt the approach of decision theory, and ask himself how likely it is that Giroud will go right or left, respectively, and use this probability to figure out his best bet. If he does this, Wilshere will find that it will pay him to pass left as long as the chance of Giroud going right is less than 80 percent, but that right becomes the best bet once it’s more than 80 percent probable Giroud will go right.*

Footballers’ Problem: Decision Theory

But surely Wilshere can do better than that. After all, Giroud is an intelligent fellow too, not a weather system. So shouldn’t a theory of rational choice predict what Giroud’s going to do too, and not just leave Wilshere with probabilistic guesses?

This is the challenge taken up by game theory. It considers the pay-offs for both players at the same time, and on this basis tries to deduce what both will do.

Footballers’ Problem: Game Theory

But now we see the problem. It’s best for them both to go left if the other also goes left. But at the same time, it’s also best for them both to go right if the other goes right. So this game has two “Nash equilibria”—where a Nash equilibrium is defined as a pair of options such that both players are doing the best they can, given what the other is doing. According to individual game theory, both these equilibria are rational solutions to the Footballers’ Problem.

This is precisely the kind of case where team reasoning performs better than game theory. We don’t want Wilshere and Giroud each individually worrying about what the other will do. They will only get in a tangle. We want them to think of themselves as a unit, and to consider which of their joint options is best.

Footballers’ Problem: Team Reasoning

Now everybody, including Wilshere and Giroud, can see that the best joint option is for them both to go left. It’s the obvious decision, as soon as they stop thinking of themselves as autonomous agents making separate choices, and see themselves as a team, committed to playing their parts in the team’s best strategy.

It is worth emphasizing that team reasoning isn’t necessarily a matter of having altruistic aspirations. Wilshere and Giroud mightn’t care about each other, or their team. They might be thoroughly sick of Arsenal’s long-standing manager Arsène Wenger, and North London, and concerned only to show they are good soccer players worth a lucrative contract at a new club. They will still do better to reason as a unit. That’s what good soccer players do.

Think of the examples of mutualism discussed in the last chapter: cyclists in a breakaway, the stag hunt, and so on. In all of these, the actors were only concerned to maximize their own advantage. But it still paid them to co-operate with the others.

In the last chapter I skated over the issue of team reasoning. I emphasized how the cyclists and stag hunters would do best to co-operate, provided the others did so too. But I didn’t stop to explain why they should expect the others to co-operate in the first place, beyond some vague suggestion that they would see this as likely.

But why should they see this as likely? This is where team reasoning does its work. If the cyclists and stag hunters are team reasoners, they can simply bypass any worries about probabilities. They only have to ask themselves, “What should we do?”, and the answer is obvious.

Sometimes team reasoning and altruistic desires work together to help people find the right answer. As we saw in the last chapter, you need some altruism to get out of the prisoner’s dilemma or similar situations. But altruistic desires on their own won’t do the whole job. Even if you care about what happens to the other guy, and you know he cares about you too, you still can’t be sure of ending up in the best place if you get caught up in the game-theoretic tangle of asking, “What’s my best strategy, if he does that?…” After all, if he is somehow rattled enough to confess, then the best solution all round will be for you to confess too. Once more the key is for you to address the problem as a team. Then you’ll have no difficulty both keeping your mouths shut and going home soon.

Economists and other orthodox theorists of rational choice hate the idea of team reasoning. They think it’s a cheat. Their Thatcherite vision doesn’t leave room for anything except individuals doing their own thing. Even when people seem to be reasoning as a team, they insist, they’re in reality each making their own rapid calculations of which individual actions are likely to best satisfy their own desires.

From the economists’ individualist perspective, if Wilshere and Giroud both automatically go left, that must be because they are both sure of what the other will do, and as a result know that they will individually maximize their expected utility by going left too.

But this puts the cart before the horse. No doubt they are both sure about what the other will do. But where did that come from? As we’ve seen, nothing in the orthodox of theory of rational choice dictates that they should both choose left. In truth, the only reason Wilshere and Giroud know what the other will do is that they both take it for granted from the start that the other is a team reasoner.

The economists are missing the point. Of course it’s true that what a team does depends on what all its individual members do. But we are talking about the psychological reasoning that gives rise to their actions in the first place, and there is absolutely nothing in logic or psychology to stop the members of a team all simply asking themselves, “What’s the best joint strategy for us to adopt?”—and then all playing their parts when they have figured out the answer. If the economists have a theory that says that the players on my soccer team can’t possibly be doing this—well, they know where they can stick their theory.

Perhaps the economists are in the grip of some half-baked evolutionary thought that natural selection favours organisms that outcompete their peers in the race for survival. Well, it’s not always as simple as that, as the last chapter showed. And, even if it were, that still wouldn’t be an argument against team reasoning. Given that the best way to further your own interests is often to think as a team, it would be odd if evolution hadn’t made it natural to do so.

None of this means that humans always think as team members. There are cases and cases. Some situations call for teams reasoning, others for us to think as individuals. Think of a breakaway composed of cyclists from different teams. At first the priority is to keep ahead of the peloton, and this calls for the cyclists to think as a unit. But, as the finish nears, the imperatives quickly alter, and it becomes natural to start thinking as individuals instead.

Many sports bring out this kind of interplay between team and individual endeavour. One of the things I used to love about cricket was this possibility of switching between these different perspectives. The best days were when your team won and you played well too. But even if your team lost you might still get runs or wickets yourself. Then there were games where a team victory made up for your individual failure. And even in the worst case, when individual failure was compounded by team loss, you could at least console yourself with the thought that the rest of your side didn’t do much better.

Nearly all team sports involve this combination of team and individual aspirations. You want your side to win, but also to play well yourself. Cricket and baseball stand out because their scoring systems automatically calibrate the relative contributions of the players. But they are by no means the only sports where you can take some pride in playing well on a losing team.

As a rule, individual and team imperatives pull together. What’s good for you is good for the team. But sometimes the two conflict. We need you to man-mark their midfield playmaker and forget the showy stuff. Your cricket side wants runs quickly even though that puts you at risk of getting out. As a group, competitive athletes are surprisingly ready to put their team’s needs above their own. Selfish teammates are very much the exception.

I can’t help digressing for a moment. When I first started playing for my cricket team, the Old Talbotians, we didn’t care about winning. The idea was to have a pleasant day out, with everybody getting a chance to bat or bowl. We lost a lot of matches and the team started struggling for players. Who wants to play for a losing side?

Then Phil Webster, for many years the political editor of the London Times, elected himself captain and ran things differently. He too made sure that everybody got to bat or bowl—but only as long as this didn’t damage our chances of winning. On one occasion we were defending a low total against old rivals and the first relief bowler leaked seven runs in his first over. Phil promptly whipped him off and went back to the two opening bowlers for the rest of the 40 overs. We won that match and a lot more besides. Phil was a peerless captain. Adding the desire for team victory to our individual aspirations made it all much more fun.

It works much better when players care about the team as well as themselves. But that’s not always enough, as the prisoner’s dilemma showed. Even if you have altruistic desires, you aren’t guaranteed to find the best solution unless you also reason as a team and so avoid second-guessing your teammates. And this can be a fragile business. Teams can lose the ability to reason together.

The danger is that the players will stop counting on each other. After all, asking, “What shall we do?” only makes sense if we can all be sure that everyone will play their part once we have decided on the optimal strategy. If this assumption is undermined, for whatever reason, then the power of team reasoning is lost.

This is what happens when teams disintegrate or choke. We can all fill in our own examples. Take Manchester United in the seasons after Alex Ferguson’s retirement, or the England rugby team in recent World Cups. It’s not that these sides weren’t bothered about winning. Far from it—they were desperate for success. It’s rather that they lost confidence in their ability to coordinate their actions. They started worrying about the others’ choices and ended up in the plight of the poor game theorist, thinking that if he does that, then I’d better do this, but if he…—and then no one is sure what to do.

Perhaps, as so often, sports point to a wider moral. In coming chapters we will look at the ways in which humans form themselves into nations, federations, and other social groups. The healthy functioning of these entities requires that their members care about each other, that they are altruistically motivated to foster the welfare of their fellow citizens as well as their own.

As we have seen, though, this concern for the common good isn’t necessarily enough on its own. Optimal outcomes also depend on our ability to reason as a team—and this in turn requires us to trust everyone to play their part once a decision is reached.

In complex modern societies, this trust can be a fragile flame. Divergent histories and loyalties can corrode our confidence in each other, and reduce us to the level of a sports team that has forgotten how to pull together. It is in no one’s interest for us to lose our faith in each other. Once gone, this kind of trust is not easily regained.