Stratford.

Back to Lear-learning, with the script on my improvised lectern in the big window. The sunshine was so bright on the text, I could hardly see it. A good sign. This project is alight now.

Thursday 5 May

It’s hard to believe, but we’re going away again – next week. I don’t feel my usual dread of packing and travelling – Greg calls it my Wandering Jew syndrome – because this is a holiday. We’ve rented a villa in Italy for a fortnight (sharing the cost with Greg’s twin sister Ruth and her husband Tony), and various friends and family members are coming to stay.

The RSC’s voice guru, Ciss Berry, turns ninety while we’re away, so we celebrated with her tonight. Dinner at the house – Greg made his delicious fish pie – and we presented her with a big bunch of flowers. Over dinner, the talk turned, inevitably, to Lear.

‘It’s Shakespeare’s Marxist play,’ she said firmly; ‘Probably the greatest Marxist play I know.’

I said, ‘Because it’s about a king finding out he’s just a man?’

‘Just one of us.’

‘And what about his irrationality in the first scene?’

She shrugged. ‘It’s what he’s used to. Absolute power.’

I hesitated, then asked, ‘Any key to the part?’

‘Of course not, darling,’ she said gently; ‘You’ll find your own way. It’s all there. It’s all in the language.’

All in the language. This is Ciss’s most heartfelt belief. Of course it’s true. And yet not. It’s not all in the language. What about the director’s imagination, the designer’s, the actor’s?

In 1988 Ciss directed Lear at the old Other Place, with my fellow countryman Richard Haddon Haines in the title role. I wonder how much leeway he had, to interpret the part?

Now the conversation changed to tomorrow’s memorial service for Guy Woolfenden.

(Guy is another RSC legend – he joined the company in ’61, Ciss in ’67 – and served as Head of Music for thirty-five years.)

‘I expect everyone will be there,’ I said; ‘Trevor Nunn, Terry Hands…’

‘Probably not Trevor,’ said Greg; ‘He told me recently that he’s had to stop going to memorial services – there’s so many, they’re overwhelming him.’

Ciss stopped eating. ‘So you mean he won’t come to mine?’

Greg and I went still. Ciss was smiling, but when a ninety-year-old makes a joke like that…

Then Greg grinned and touched her arm: ‘Ciss, I’m sure he’ll come to yours.’

Friday 6 May

A beautiful Stratford spring day – perfect weather to honour an RSC great.

As I arrived at Holy Trinity Church, I bumped into Jim Jones (lead percussionist in the RSC band). He was smartly turned out, in black suit and tie; he’d worked closely with Guy over the years. Mentioned that he’d watched Greg’s Dimbleby Lecture, and said, ‘It made me very proud – proud to be working on Shakespeare, and proud to be doing it here.’

I was touched. Jim can sometimes seem like quite a gruff character. I didn’t expect him to feel like that. I promised to pass it on to Greg.

There was lots of Guy’s finest music in the service, Greg gave the address, Harriet Walter did a sonnet, and David Suchet a Psalm. And I read a short extract from Year of the King, which told the story of Guy teaching the Richard III company to sing the ‘Gloria’ for the coronation. Some of the actors complained that it was set too high. Guy said, ‘D’you know, I was watching football on the telly last night, and I was amazed at how high the crowd was singing “You’ll Never Walk Alone”. I dashed to my piano and it was indeed a fifth higher than I bet any of them thought they could sing. The adrenalin supplies the boost!’ There were no more dissenters after that.

So – a splendid service. Lots of laughter, lots of love.

Trevor wasn’t there, but Terry was.

Later…

A few tryouts (known by the German word, Bauprobe) for the Lear set. Held in one of the huge new rehearsal rooms in the converted Courtyard. There was a rough version of the palanquin which will carry me on – it’ll need eight people to lift it. Then we looked at the fog box, which will be revealed on the back of the stage after Gloucester’s blinding. The outer surface was cloudy, and then, when smoke was pumped inside, any moving figure became a ghostly shadow. (It reminded me of Antony Gormley’s art installation, Blind Light, in his 2007 exhibition at the Hayward.) This is how Greg plans to do the battle – which is one of the most curious battles in all of Shakespeare. Edgar leads Gloucester on, and tells him to wait under a tree. Edgar exits. The battle ensues, very briefly. (In the text, it just says: ‘Alarum and retreat within.’) Edgar re-enters, says Lear’s side has lost, and leads Gloucester off. The battle itself has been, in fact, witnessed by a blind man. So just glimpsing it in a fog box could be very effective.

Then they showed us the stage floor being hoisted up to become the cliff/sky in the storm. Various wind machines were turned on behind the cloth. The biggest was very impressive, but very noisy, like a jet engine. Our producer, Zoe Donegan, leaned over to me: ‘The person who invents a silent wind machine will make a fortune.’ But Greg is convinced that if Graham Turner and I wear radio mics, and Ilona’s music is boosted loud enough, we can top it.

Afterwards, Niki Turner asked if I’d like to see the latest costume designs. She’s a skilled draughtsperson, and the images of different characters were very striking. A dark, mostly black palette, with strains of colour, and the metallic glint of ornamentation or armour. The Fool was in white – a kind of Pierrot figure, but not overly specific. And Lear himself looked tremendous in his enormous fur coat. I’d asked for the colour to be changed from black (too much like Scofield) to silver fox, and it’s worked.

Went home very excited.

Sunday 8 May

Did all Lear’s lines. Pretty ropey. I’ve got to the stage where I need to note down my regular stumbles, to practise them again and again, to get rid of them!

As I came out of my studio, Greg saw that I had tears on my face.

‘What’s the matter?’ he asked.

‘I’ve just done King Lear, and you ask what’s the matter?!’

‘Ahhh,’ he said with mock sympathy; ‘Was it very moving?’

‘Well, the play was very moving, and I was very incompetent, and both things upset me.’

Tuesday 10 May

Packing for the holiday, the question is whether to take my script or not?

I think yes.

Greg thinks no.

I say, ‘But I could work for a couple of hours each morning.’

He says, ‘Absolutely not. This is a holiday. For us, and for all our guests.’

‘Oh, this is ridiculous – I’m arguing with Lear’s director about me knowing Lear’s lines!’

‘You’ll know your lines. You know you will.’

(Well, we’ll see. Maybe I’ll smuggle the script in my hand luggage…)

Wednesday 11 May

Rome.

Our hotel, the Palazzo Manfredi, has an astonishing location. Right opposite the Colosseum. The sunken ruins of the Ludus Magnus (Gladiator School) is the only thing between us and Rome’s most iconic building. You can even see it from our shower!

Rather incongruously – or, then again, maybe not – there’s also a gay area to one side of the street, with bars and shops, all showing the rainbow flag. Well, it’s not our scene. We were fast asleep by 9.30 p.m.

But then, some time later, we were woken by cheering from that direction, and people making speeches.

Turned out that the Italian Parliament finally granted the Civil Partnership Law today. They’re one of the last countries in Europe to do this, and it was against formidable opposition, from the Vatican, of course. They’re not allowing gay marriage yet, but it’s still an enormous step.

We felt rather chuffed to have arrived on such a historic day.

Friday 13 May

We’ve had a terrific little stay in Rome (before moving to the villa tomorrow). Having been here several times before, we felt no pressure to see the sights, but nevertheless visited some of them when we were in the mood. Greg wanted to focus on Ancient Rome, as his appetite grows for the adaptation of Robert Harris’s Cicero books.

We even found a bust of the Great Orator in the Musei Capitolini, and I took a photo of him and Greg together. But for me the best moment here was a spectacular view of the Forum from a balcony at the back of the building. If you kept your eyes wide open, yet halfclosed your conscious mind, you could almost drift back in time…

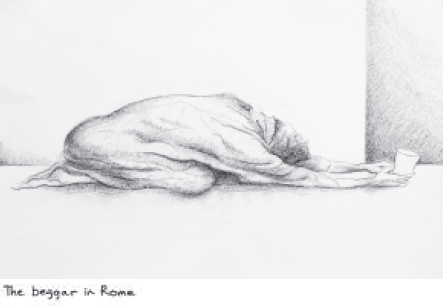

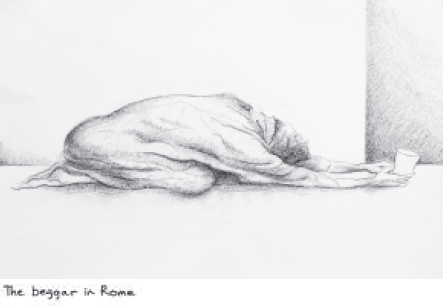

However, there’s one image from today, not from the past but the present, that I’ll never forget. It was late afternoon, there was quite a drizzle, and we were hurrying to San Pietro in Vincoli before it closed, to see Michelangelo’s statue of Moses. At the entrance to the church, there was a figure on the ground, female I’m pretty sure. She was kneeling back on her haunches, with her torso stretching forward, flat on the paving stone, head bowed under a scarf, and with arms reaching out in front. At first I thought it was a position of devout payer. Then I noticed that her hands were holding a plastic cup for money. Someone dropped in a coin. The figure didn’t glance up, didn’t stir. She was drenched through by the drizzle. The folds of her clothes were heavy with water, making them look like the drapes on a marble carving. The whole impression was classical – a classical pose of utter abjection. I wondered if this woman was an ex-dancer? I don’t think anyone else would be able to conceive and sustain a stretch as long and low as this. Most passers-by, ourselves included, just stopped in their tracks, and stood staring down at her, quite dumbstruck.

For the rest of the day, I felt haunted by what we’d seen. Later, we got talking about Lear. There’s a surprising number of references to beggars in the text, and Lear has a famous speech in one of the heath scenes:

Poor naked wretches, whereso’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your lopped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these?

It’s as if, for the first time in his life, the king has noticed that homeless people exist.

Greg wondered if we should actually show them during the speech – vagrants lost in the storm?

But how could we ever make the actors look like that woman did today, and how could we ever make the audience feel what we, the onlookers, felt today? That sense of shame.

A testing day:

Hiring a car at the airport, meeting Richard Wilson off his flight, then driving to the villa.

We achieved the first task without a problem, and were then waiting in the café in the Arrivals Hall, wondering when Richard might appear. Suddenly a British family surrounded a woman at the next table, hugging and greeting her: ‘You’ll never guess who we had on our flight – Victor Meldrew!’ Cue for us to move forward.

When Richard joined us, I told him, and said, ‘Now that’s fame!’

He wrinkled his nose: ‘So there are some plusses to it.’

He turns eighty in July, and, as a humble attempt to answer the question, ‘What do you give the man who has everything?’, this holiday is our birthday gift to him.

The next phase was difficult: driving an automatic car (at home, ours is manual) on the right-hand side of the road, some ninety kilometres north to the Maremma area of the western coast. I am hopeless at these things – both driving abroad and reading maps – so thanks be to God for adding them to Greg’s gifts.

About two hours later, we reached the seaside resort Ansedonia, and, turning up through a twisting network of little roads, finally arrived at the Villa Solemar. It was as splendid as it looked in the photos: big blue pool, big blue view of sea and sky, and a peaceful fragrance in the air. We sensed we were going to be happy here.

Tuesday 17 May

Woken in the night by a ferocious storm, with great bangs of thunder and flashes of white lightning glinting through the wooden shutters in the bedroom.

‘I thought it was rather exciting,’ said Greg this morning.

‘I thought rehearsals had started,’ said I.

At lunchtime, Ruth and Tony arrived, having flown from their home in Denver, Colorado. I’m tremendously fond of them, and we immediately fell into those easy, familiar rhythms of being together.

The villa has five bedrooms, which will be occupied by a changing population while we’re here. Fortunately, there’s a housekeeper – a sparky young Bulgarian lady, Tatiana – to keep things running, while her husband works as gardener and odd-job man.

Thursday 19 May

The South Africans arrive! My brother Randall, and our friends, Janice (Honeyman, theatre director) and Liza (Key, documentary film-maker).

Randall and I are both on the brink of big emotion – it’s the first time we’re seeing one another since Verne died. He has brought a special gift: two photos, framed together, showing the siblings. The top one is from 1955 (Joel has just been born, I’m six, Verne is nine, Randall is twelve). The bottom one is from our visit home last year, October 2015, when Verne turned seventy, and we all celebrated her birthday. These are probably the first and last photos of the four of us together.

The floodgates open, and we have a good cry together.

I’ve known Janice since schooldays in Cape Town, and in adult life she’s directed me twice at the RSC: Fugard’s Hello and Goodbye (1988) and The Tempest (2009). She’s one of the most joyous people I know, and it’s always a pleasure to watch newcomers, like Ruth and Tony, instantly fall in love with her.

[See Photo insert]

Friday 20 May

So – our days are falling into a comfortable pattern.

Mornings are spent at the villa. Mostly by the pool – though I’ve noticed that Richard has found himself a corner of the garden, where he sits and learns lines, for a one-man show he’s doing at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in August. Having surrendered to Greg’s instruction not to bring my Lear script on holiday, I scowl and mutter whenever I see Richard doing this.

Lunches are in one of the neighbouring towns: Magliano or Porto Ercole, where a particularly favourite restaurant is Gambero Rosso (Red Prawn).

In the evening, one of the cooks among us volunteers to make dinner, and then entertainment is provided by the DVDs Richard has brought along. Tonight I saw the work of a great movie-maker, who was new to me: the Swedish director Roy Andersson. His film You, the Living is an astonishing piece of absurdism, surrealism, not sure what to call it. Some of our party couldn’t get into it at first, but Janice led the way, laughing so much, so hysterically, she had to stuff her scarf into her mouth. It was very infectious.

Saturday 21 May

Richard departs, thanking us with great warmth, and Jo arrives: Greg and Ruth’s older sister, who lives in North Wales. She quickly, happily, settles into life at the villa.

Monday 23 May

Ruth and Tony head off for an overnight in Florence, Greg takes the others to do a big shop at the supermarket in Orbetello, while Randall and I find a sunny spot in the garden for a little gesels (talk). His situation is grim. Yvette is becoming more and more ill, yet won’t go into a care home. So all the pressure is on him, as main carer (for whom the South African health system offers no financial help whatsoever). I don’t know what to suggest. These little holidays are all we can provide, although they’re only very brief, very temporary respites for him. But he is never self-pitying. He has a quality which, oddly enough, our Jewish family always call ‘saintly’. And they’re right. On the other hand, he smokes all the time, and the sound of his cough isn’t great.

Thursday 26 May

It’s our twenty-ninth anniversary. (We date this from the beginning of our relationship, rather than our civil partnership or marriage, which was simply the law catching up.) Greg has always said there’s a Shakespeare quote for everything, and proves it this morning. He gives me a card which he commissioned the RSC calligraphy writer to inscribe: ‘I have known thee these twenty-nine years come peascod-time.’ (It’s Mistress Quickly talking to Falstaff in Part II.)

We’ve planned a tour for the day, and hired a people-carrier with driver, because we suspect there’ll be a drink or two taken before we return to the villa.

First stop is the Saturnia Thermal Springs. Entering the foyer, the stink of sulphur hits us, that rotten-egg stink, but the manageress reassures us we won’t notice it after ten minutes. (She’s right, thank goodness.) Then she leads us to the main outdoor pool. Again, reassurance is needed. Among the hot bubbles rising up from the volcanic crater below, there are also little brown blobs, which float about. These are plankton, she says, and not what we’re all thinking.

We change into our bathing costumes, and enter the pool tentatively. It’s surprisingly warm. The manageress advised us to apply lots of sun lotion, and only remain in the water while it feels comfortable. People have different tolerance levels to the experience. I’m keen to stay submerged for as long as possible – I’m hoping, seriously hoping, that the springs’ legendary healing powers might have some affect on my bad arm.

And to my amazement, when I get out, there is a marked improvement in flexibility and stretch. I’m about to sing out, ‘I’m cured, I’m cured!’ when I realise that the new feeling is already fading. It was simply the temperature of the water. Any heat treatment would’ve done the same.

We lunch at the poolside restaurant. When the group toasts our anniversary, Janice adds, ‘And what a way to spend it, hey, boys?’

‘Indeed,’ I answer; ‘In a big warm bath with lots of loved ones and a few floating turds.’

Back in the people-carrier, heading for the next destination, people start dozing off. My thoughts drift to Lear. The holiday is almost over. Then there’s three weeks. And then we’re off.

I feel sensations of both excitement and dread, but that’s completely normal.

On the one hand, this is probably the most challenging role I’ll ever play.

On the other, I’m in top condition for it. I don’t mean mentally, and certainly not physically, but simply in terms of Shakespeare skills. I’ve just spent two years playing the double whammy of Falstaff. In retrospect, I was like an athlete preparing for the Olympics. I’m now ready for the main event. I think.

About an hour later, the vehicle pulls into a lay-by halfway down a mountain. We climb out, turn to see the view, and everyone’s face lights up with wonder. Across the valley is a hill, and on top of it, high, high in the air, is a walled town. Pitigliano. Built in Etruscan times. But built how? God only knows. The steep rock cliffs of the hill sweep upwards, and at some, invisible point, change into the stone of the town, creating a magical balancing act.

Once you’re inside the walls, Pitigliano looks like any other quiet Italian town, with cats stretched out in the sun, old ladies in black sitting outside their front doors, and the usual array of souvenir shops, ice-cream parlours and bars. However, there is one unique feature to this place. It is known as La Piccola Gerusalemme or Little Jerusalem. In the early part of the sixteenth century, it developed a big Jewish population – mainly from the nearby Lazio region, which bordered the anti-Semitic Papal States. Jews remained here for many centuries, with mixed fortunes (in 1622 they were confined to a ghetto, and forced to wear red hats or badges), but survived on until 1938, when the Fascist racial laws came into being. Today there are no Jews left. Yet, incredibly, there is still a synagogue. We set off to find it.

We descend a narrow alleyway of steps, turn the corner, then stop in surprise. Standing outside the synagogue, which is shut, are two Italian soldiers, in full uniform, holding automatic rifles. They seem relaxed and friendly, so clearly there’s no current trouble. In fact, I wonder which recent world event caused the Italian government to create such security for the one little shul left in Little Jerusalem?

Returning to the villa, we’re all very happy. It had been, as Janice put it, ‘One helluva nice day!’

Friday 27 May

‘Can we talk Lear for five minutes?’

‘Sure.’

Greg closes his book (one of the Robert Harris trilogy). He’s lying among a pile of cushions on the long bench at the end of the front terrace – or stoep as the South Africans say – which has become his favourite place during the holiday. Especially late afternoons, like now.

I hand him a G&T, and sit next to him: ‘It’s about “the look”. You’ve said several times you don’t think I should wear a wig. Why not?’

‘Because I want you to be more yourself, to be more natural. If you want to touch your hair, I don’t want you to be worrying about a wig.’

‘But my hair’s dark. You can make dark hair grey, but it’s practically impossible to get it white. It goes bluish. So we’d have to change lines like “A head as old and white as this”.’

He thought for a moment. ‘Maybe have a number-one cut?’

I thought for a moment. ‘Yes… be easy to whiten that.’

We sipped our drinks. ‘So,’ I said; ‘Cropped hair and my own beard, which has got real white in it already. But of course that’s the Lear-look from the Simon/Sam production at the National – so we’d be stealing it from them.’

‘That’s okay,’ said Greg, slightly gleefully; ‘They stole the death of the Fool from Adrian’s production with you and Gambon.’

‘True,’ I said.

‘Good,’ he said, and reached for his book.

I leaned forward: ‘But – sorry – I’m also tempted by eyebrows.’

‘Eyebrows?’

‘I was so pleased by Falstaff’s eyebrows – how they change the face – widened it in that case – but now let’s make them more ferocious – thick, heavy, still black despite the hair and beard – a bit like your dad’s.’

I phrased this delicately. When I first met Greg’s father, John, his big dark eyebrows were so intimidating it took me a while to realise that, behind them, there was a very sweet man. And then, much later, was the long period when John’s dementia set in, which made it impossible for Greg to watch Lear.

‘Dad’s eyebrows…’ Greg said slowly; ‘Yes, good.’

We went quiet. The sunsets here, like all around the Mediterranean, cast the most beautiful light onto human faces and skin: a rich, reddish colour which is almost like the terracotta you see on local vases and pots.

‘Thick eyebrows, cropped hair, big beard,’ I said: ‘I’ve been wondering for ages what Lear should look like. But maybe we’ve got it.’

I went to our room and tried a sketch.

I think we’ve got it.

We sang ‘Happy Birthday’ over breakfast – today was Randall’s seventy-third – and then began the sad business of parting again. We all fly away today, to different parts of the world.