![]()

![]()

THE SIGNORELLI SELF-PORTRAIT AND THE FIGURE next to it are to the left of the entrance to the chapel. This is the first place to which most viewers instinctively turn upon entering the room. While everyone else in the large scene is in a sort of historical costume that suggests biblical times, these two men, in dignified black tunics and capes, with black leggings and black shoes and black headgear, seem contemporary with the making of the fresco. So they were—one precisely, the other by the relatively small gap of half a century. The more modest-seeming man behind Luca Signorelli is none other than Fra Angelico—the great early Italian Renaissance master best known for his sublime frescoes in the cells and public spaces of the monastery of San Marco in Florence. He is there, the Karpes tell us, because he started this painting and planned the others in the chapel fifty years before Signorelli was commissioned to complete them.

I imagine that most visitors to the chapel have no idea about any of this. I certainly would not have known who the two figures in modern everyday dress (for the year 1500) were had I not read the Karpes’ narrative. I wonder if Signorelli gave any thought to what viewers five centuries later would think. What is certain, however, is that, once we indentify these two individuals, the way Signorelli has depicted himself dominating a recalcitrant Fra Angelico is provocative. From where they are standing on the side of the panorama of scenes of the Antichrist and his kingdom, the man whose shoes Signorelli filled appears to be looking back sideways into the tableau, while Signorelli himself is distinctly staring away from it and surveying the entire room. Angelico appears dissatisfied, as well he might be, given how little he completed of the work he set out to do in the chapel. Signorelli is the master of ceremonies.

The younger artist, nearer to us, blocks Angelico with his vast cloak and billowing sleeves. He splays his legs to make himself immobile. His thick, luminous locks under a jaunty, billowing tam have a bravura lacking in Angelico’s tidy, smooth hair under a tight skull cap. Angelico is distant, in a state of reverie; Signorelli is knowing and confident.

In fact, for Luca Signorelli, Fra Angelico was a hard act to follow. To show himself dominating Angelico is true hubris. When Angelico, a Dominican monk, had been asked to work on the Cappella Nova in 1447, he was deemed “famous above all other Italian painters.” The Pope had recently commissioned him to paint frescoes at the Vatican; for at least three decades, he had enjoyed immense stature for the quality of light in his work, esteemed for its visual elegance and spiritual magnitude. He skilfully utilized recent discoveries about how to represent perspective, and his figures were clearly articulated and possessed of volume.

The authorities of Orvieto, called the Opera, were proud to have landed such a master. By the time be began work on June 15, 1447, they had agreed to furnish scaffolding, supply all the colors—except for the particular blue and gold Fra Angelico liked to use, which were inordinately expensive—pay salaries to the artist’s assistants as well as to Fra Angelico himself, and supply bread and wine along with a per diem. The agreement was that Fra Angelico would work for three to four months each year during the hottest summer season, which suited his goal of escaping the heat of Rome and the weather-related illnesses that went with it.

But Fra Angelico spent only one summer in Orvieto. We don’t know why—whether the main factor was the demands of the Pope, or financial difficulties encountered by the Opera that prohibited their being able to cover all the high expenses—but, once he had made an overall design for the chapel, all that the Dominican executed were a Christ in judgment and some prophets.

I am sure that Fra Angelico’s Christ, enclosed in a circle high above in one of the ceiling vaults of the Cappella Nova, is a beautiful painting: serene and magisterial. But while I acknowledge those qualities as facts, I cannot feel them. Even though I looked up at Fra Angelico’s Christ dutifully on my two Orvieto visits, on both occasions fully aware of its importance as a work by a painter whose art normally bowls me over, it had little impact on me. One knows it is great—a triumph of competent modeling and serene vision, a perfect visual representation of equilibrium—yet, with all the drama and naughtiness below, all the titillation and provocation, it is impossible, at least for me, to respond to the quietude. To become absorbed by it would be as difficult as doing justice to the subtle flavor of a white truffle accompanied by a glass of Puligny-Montrachet when one has just been eating barbecued ribs and drinking stout; the timing makes it impossible to appreciate what would otherwise be a marvelous experience.

Like the Christ, Fra Angelico’s prophets are beautiful: possessed of grace, clothed in robes of soft chalky colors. With their half-closed eyelids, their pale and luminous skin, and their look of being in receipt of a message, they seem truly holy. When we see them in reproduction, and not in the direct company of the Signorellis, they have fantastic grace and beauty. But when we are in the Cappella Nova, they don’t attract us any more than the perfect child in class does when the macho, bold, bad boy is acting up.

Based on the Last Judgment that Fra Angelico painted elsewhere, if in fact he had been the one to complete the cycle, it might have had an aesthetic grace and refinement lacking in Signorelli’s frescoes, but it would not have been nearly as exciting. There is a small Last Judgment by Fra Angelico on extended loan from an unspecified private collection to the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and while it has splendid colors and consummate grace, it is absent of all drama. The damned are almost as innocent-looking as the blessed, and they are totally without corporal, let alone sexual, traits.

Normally, if I am in a museum that, like the Louvre, has work by both Fra Angelico and Luca Signorelli, I find the work of the former infinitely more moving. It is poised and serene, and it fills me with a sense of well-being. Even scenes that could be scary or threatening, a beheading or a crucifixion, have a biblical grace to them. The sheer beauty is more impressive than the terror. But in Orvieto, aside from the issue of visibility, the art of the man whose name suggest an angelic monk doesn’t hold a candle to the rough, in-your-face presence of work by someone whose name signifies “light on the little man.”

IT TOOK HALF A CENTURY BEFORE THE OPERA FOUND someone to continue the chapel. Starting in about 1490, they tried to convince Perugino to take over where Fra Angelico had left off, but they failed to lure him to Orvieto. It was in 1499 that they got Signorelli. He was, at the time, painting a large cloister in the monastery of Mount Oliveto Maggiore, near Siena. With the subject matter of the life of Saint Benedict, he had already managed to put on display some swaggering lads in very tight pants. [plate 8] Seen from behind, they could be modeling for Abercrombie’s; in one instance, Signorelli has torn the leggings off of a young man to expose his bare thighs and underwear. [plate 9] But he had no problem leaving it unfinished when Orvieto beckoned. Dugald McLellan—an excellent contemporary art historian whose small book on the Cappella Nova frescoes I bought from the ticket seller on my recent visit there—posits as to his reasons: “It is not clear why Signorelli abandoned that commission, but he was clearly keen to take on the Orvieto project. Perhaps it was the chance to cover such a vast, virtually uninterrupted space; perhaps it was the prospect of depicting monumental scenes of nudes in a range of different moods and states that motivated him.”

Signorelli was in his fifties when he received the commission for the Cappella Nova. (By most estimates he was born circa 1441.) He was from Cortona, a town in Tuscany near the Umbrian border, and he had served as an apprentice under none other than Piero della Francesca. He may have learned technique from Piero, but he acquired little of the sensibility of that most subtle and magical of painters. Once he started his own workshop, he clinched commissions for altarpieces and frescoes from towns all over central Italy, and he was employed by the Vatican—during the early 1480s in the recently built Sistine Chapel—as well as by the Medici in Florence.

Plate 8. Life of St. Benedict: How Benedict Recognizes and Receives Totila, c. 1498–1499, fresco, great cloister of the Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, Asciano, Tuscany, Italy

Plate 9. Detail of Life of St Benedict: How Benedict Reproves the Brother of the Monk Valerian, c. 1498–1499, fresco, great cloister of the Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, Asciano, Tuscany, Italy

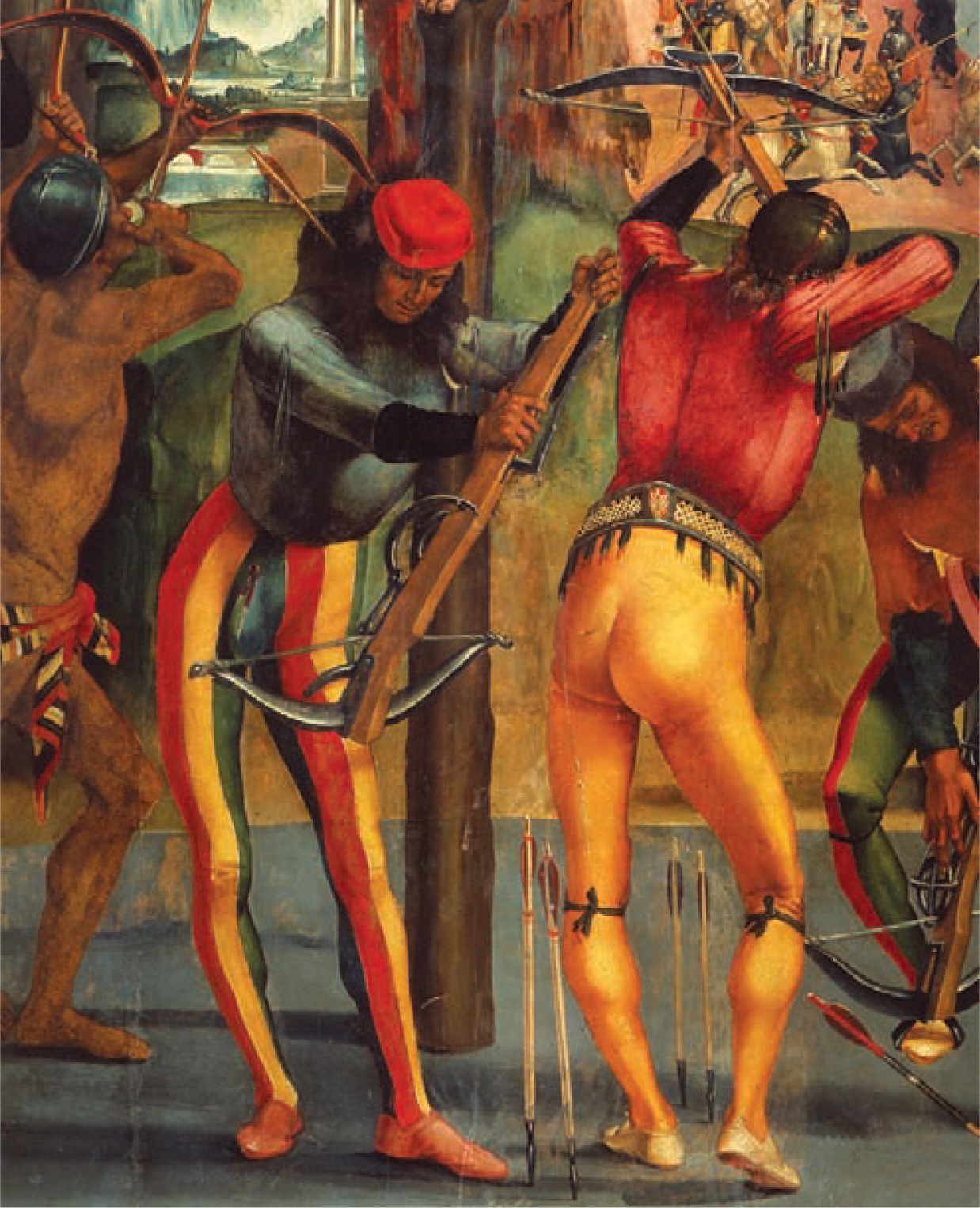

By the time he was summoned to Orvieto, Signorelli had developed a specialty of the male nude, which he painted in varying poses, sometimes completely at rest, sometimes engaged “in violent action.” Almost every artistic subject was an excuse for painting naked men, burly and strong. Although I have never found another writer who acknowledges it, his paintings are vividly homoerotic. This was evident as far back as one of his earliest works, an image of Pan, now in Berlin, which Bernard Berenson would single out as one of the painter’s triumphs. [plate 10] Pan was followed by Signorelli’s depiction of two lads, and its companion picture of a man, woman, and child, both now in Toledo, Ohio, which are equally homoerotic. [plate 11] His 1482–85 Flagellation, about which scholars differ on the dates, some saying c. 1475, others saying 1480–83, now at the Brera, in Milan, shows a muscular yet rather feminine Christ looking as if he is in a sort of reverie while being flogged by three whippers who arch their backs to flaunt their ripped torsoes; the artist presents all these men in the nude except for loincloths that fall well below their waists, to show, depending on whether we are seeing the fellow from front or back, a bit of bottom crack or pubic hair. [plates 12 and 13] In his 1498 Martyrdom of St. Sebastien, painted in oil on wood, he took the well-known theme of the saint pierced by an arrow and sexualized it, as well. Here Signorelli simply pulled down the pants of one of the archers, while leaving his fringed blouse on; the reproduction of this painting says more than anything I could possibly put into words. [plate 14] But in Monte Oliveto he had, for the most part, to tone things down and covered most of the men in white robes.

Plate 10. Court of Pan, c. 1484, oil on canvas, formerly in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin; destroyed in 1945

Plate 11. Two Nude Youths and Man, Woman, and Child, c. 1488–1489, oil on panel, from the Bichi Chapel of the Church of Sant’ Agostino in Siena; Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio

Plate 12. Flagellation, c.1475 or 1480–1483 [scholars differ on the dates], oil on canvas, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy

Plate 13. Detail of Flagellation, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy

Orvieto would provide the chance to resume painting male nudity. While his task in the great cathedral was ostensibly to complete the decoration Fra Angelico had begun in the ceiling vaults, there is little doubt that what most attracted him was the potential to fill the bare, flat whitewashed walls below with his preferred subject matter, and take it to new extremes.

The scaffolding that had been erected for Fra Angelico half a century earlier was still in place when Signorelli began. Starting on May 25, 1499, he and his assistants used it to complete the scenes for which Fra Angelico had left drawings. Then they painted, in accord with instructions from the Opera, the four segments of the entrance-bay vault. Here they put images of virgins, patriarchs, martyrs, and the doctors of the church. But none of this is what interests us, because all these paintings are overhead at a great height, making them so difficult to see that they could not have had the impact on Freud of those paintings Signorelli painted next—pictures of the Antichrist, the damned, the elect, and other scenes of the end of the world.

Plate 14. Detail of Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, ca 1498, oil on panel, from the San Domenico, Città di Castello; Pinacoteca Comunale, Citta di Castello, Umbria, Italy

Dugald McLellan does a nice job of imagining the reactions of Signorelli’s patrons when he “laid before the Opera his bold and daring plan for the decoration of the walls of the Chapel. No doubt impressed with the speed of his execution, the worthy burghers were well disposed toward Signorelli. Their reaction to the plan itself can only be guessed at, however, since the prospect of acres of naked flesh must have shocked the sensibilities of many of them.” In addition to the subject matter, there was the cost: They were about to spend a fortune for that rich display of male bodies.

The contract for the further work in the Cappella Nova, approved on April 27, 1500, was very precise. In the archives of the Opera del Duomo di Orvieto, it is a document that portrays the workings of the society in which it was created. With its elegant calligraphy in perfectly straight lines, it testifies to the fine machinery of the art world of Renaissance Italy. This legal agreement for the presentation of passion, of sin and the wages for it, left little to chance. It specified that Signorelli would receive 575 ducats “for his labours, paints, designs, and cartoons—as well as grain and wine. The Opera would maintain the scaffolding and supply the materials that would be used to mix and apply the plaster, and find room and board for two people. Signorelli, in return, would be obligated to follow the designs he had presented. While the contract allowed him to add to the number of characters he showed in his sketches, it prohibited his reducing the number. It also required him to paint the principle figures with his own hand, thus eliminating the diminution of quality that can occur when assistants and apprentices do too much work.

For four years, this is what he did. The result was his masterpiece; he would live some twenty years more, but never equal the frescoes in Orvieto.