![]()

![]()

HAVING TAKEN FREUD TO HIS ETRUSCAN REPRIEVE, the Karpes provide the detail that after his death the great psychoanalyst’s cremated remains were buried in an Etruscan urn. Unfortunately, they do not specify if this was because of his instructions, or if it was decided by others in honor of his taste.

Then the Karpes take a last look at Freud and Signorelli. Freud was, they tell us, deeply interested in demonology and associated the devil with sexuality. Earlier in the same year that he went to Orvieto, he had written Fliess, “When I am not afraid I can take on all the devils in hell.” Referring to his own ideas on the origins of hysteria, he wrote that “the medieval theory of possession was identical with our theory.”

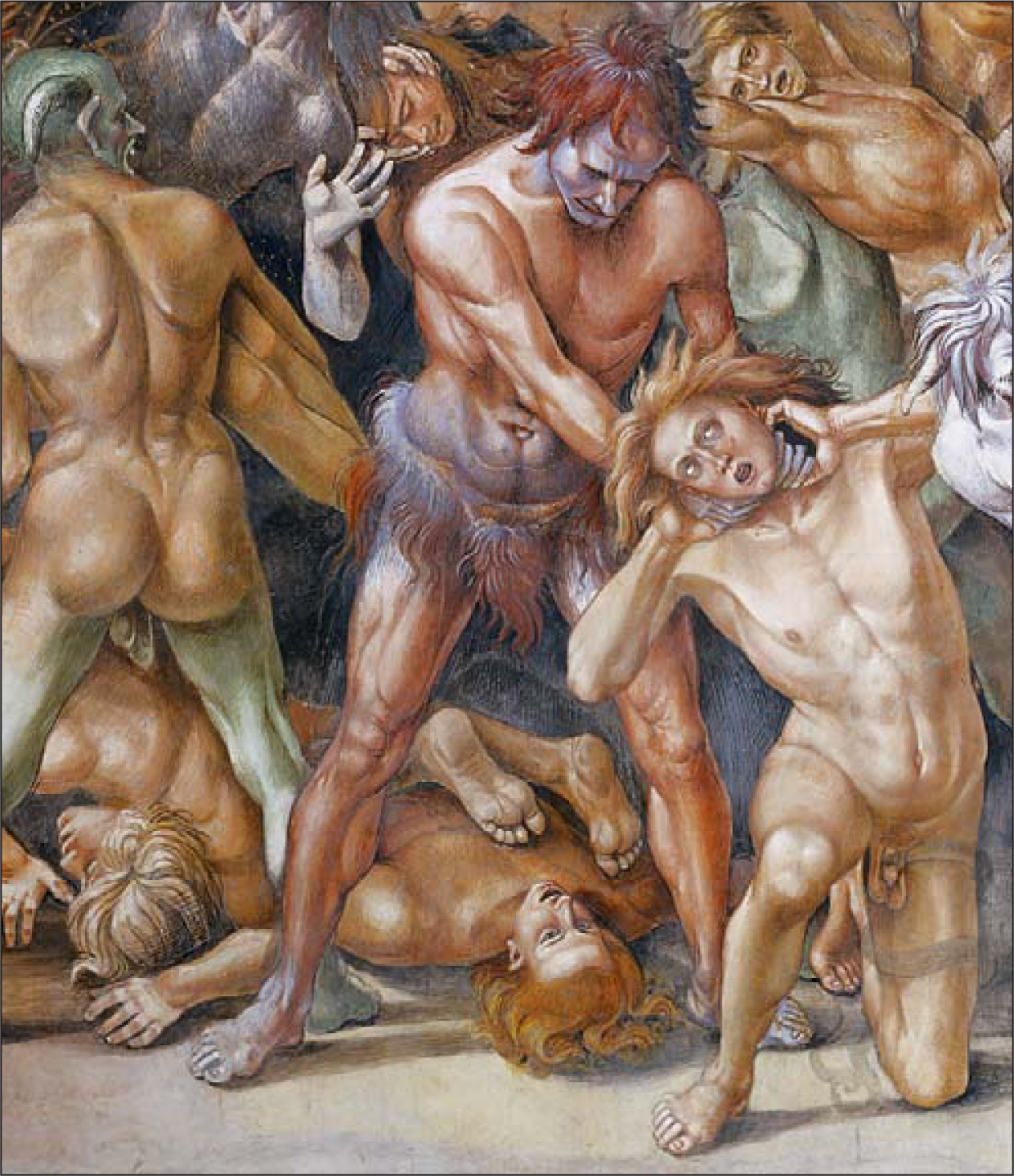

Richard and Marietta quote a question Freud asked Fliess, which would make the perfect caption to some of the images by Signorelli that Freud would see a few months later: “Why were the confessions extracted under torture so very like what my patients tell me under psychological treatment?” Here one has to wonder whether Freud, when he stood in front of Signorelli’s Inferno, with its forty or so stark naked characters falling all over one another as they are being shoved and dragged toward the flames of hell, had some image of himself and his coprofessionals as the equivalents of the devils, and of their patients as victims.

Is that healthily tanned buck of a man on the lower right Freud’s worst fear of what it means to be a psychoanalytic patient? [plate 24] With his head snapped back (the neck would be broken if his chin were really at that angle) by a devil whose skin is a corpselike white tinged by gray, he is the image of someone having his mind manipulated. This handsome lad—in today’s lingo, we would say he looks like an amiable, clean-cut jock—grabs the devil’s arm in a last effort to push him off, but it is too late; his life has effectively been destroyed by the horned creature who has a mass of animal fur covering his genitals. (Either that, or the fur replaces his genitals.)

Plate 24. Detail of The Damned Cast into Hell

And what about the duo just to the left of them? Here the victim, still alive, is howling in pain as the devil pulls tufts of hair with both hands. Again, the place where the devil tortures his victim is the head, the seat of psychoanalysis.

In this second pairing, the victim, like the first one, is a fine physical specimen with noticeably healthy skin. The devil, by contrast, not only has hair that looks like the flames of a roaring fire, and a face that personifies evil, but his body is as sinewy as the figures in medical drawings, and, while his buttocks are a truly ghastly green, his shoulders and ankles are a hideous purple.

Plate 25. Detail of The Damned Cast into Hell

In another pairing, a devil who is consistently a horrible grape color except for his green ankles, and who also has the telltale flaming hair, is crushing his patient’s head with his left leg. The victim/patient, in this case a woman, is, as usual, a far finer physical specimen than her torturer. Her large breasts and well-rounded buttocks would give her a soft voluptuousness, the sort of womanliness we find in Aristide Maillol’s sculptures celebrating female attributes otherwise absent in Signorelli’s world, but her bodybuilder’s arms and shoulders and football player’s legs are so distinctly male, and the breasts and buttocks themselves so solidly muscular, that she loses all womanly allure. Besides, hers is hardly a pretty face, and, as my mother would have said, “her hair is a disaster.” [plate 25]

To their left, as we face the painting, we have another tragic pairing. [plate 26] Here it is the devil who is in better shape than the victim. But while he is bronze-skinned, muscular, and lean, he has a grim mauve face, and an especially volcanic head of hair. What is either a bizarre loincloth or a natural outgrowth of fur at his crotch—it looks like long, wet pubic hair—makes him all the more monstrous.

Plate 26. Detail of The Damned Cast into Hell

The victim could be one of the angels from Piero della Francesca’s frescoes in Arezzo. He has similar features to them, their very round eyes, and the same shoulder-length blond hair. But while Piero’s angels are ineffably serene, he is in agony. The devil is choking him, and his efforts to pull the devil’s hands away are futile. The hair of his double in Arezzo flows with a soft curve; this angel’s locks shoot from his head as if he is receiving a high-voltage electric shock. The poor fellow has a rather feminine body; his pectoral muscles are far less impressive than the devil’s, his biceps are not as developed, and his belly is slightly rounded, Moreover, we cannot help noticing, because it is directly in front of us, and because his pubic hair is so scant, that he has an unfortunately small penis that falls far short of his testicles—which, in turn, sag like an old man’s. His mean conqueror is more fit and more virile.

FREUD WOULD, RICHARD AND MARIETTA TELL US, write that the devil was the “personification of the unconscious instinctual life.” Do these images by Signorelli suggest that to be gripped by what is unconscious and instinctual is to be strangled or crushed to death?

Given Freud’s take on the devil, he could well have seen Luca Signorelli’s paintings of victorious devils and hapless victims as illustrations of the horrible consequences of our “unconscious instinctual” feelings. If Signorelli’s demons represent the erotic longings that are beyond our plans or expectations, the tortures they inflict are the price one pays for being overcome by such feelings.

In the top half of the lunette, two of the damned have just been dropped by the devils above them, so that they cascade toward the mayhem below. One has his arms tied behind his back, and falls faceup and headfirst; it is as gruesome a form of descent as one could imagine. He has his right leg bent as if he will make a pathetic attempt to brace himself, but the effort is futile. The other, shooting down in a backward nosedive, has his legs splayed awkwardly and his arms spread in a last-ditch attempt to find some means to anchor himself. But clearly he doesn’t have a chance.

One of the few women sinners is being flown directly toward hell on the back of a devil with fantastic pointed wings and lethal horns. He leers at her while holding her hands tight to prevent her from escaping. She is built like a man, albeit a flabby one with too much girth, but that in no way discourages the devil from looking ecstatic at the prospect of raping her. Luca Signorelli’s imagination knew no limits.[plate 27]

If the artist had not presented Freud with sufficient images of torture in the contorted creatures being strangled and kicked and mutilated below, he did so in these pairings above. The consequences of sin (Sexual disinhibition? Realizing one’s Oedipal fantasies and killing one’s father? Being Jewish? Freud could have picked any of these violations, or a combination, as the vice of the moment) are utterly horrid. Equally, the prospect of death, now more than ever in Freud’s thoughts following his father’s recent demise, is made all the more terrifying by the way that what comes after it is even worse than the event itself.

Plate 27. Detail of The Damned Cast into Hell

Was this nightmare the fate of human beings if they acted according to the innate instincts that were Freud’s preoccupation, or simply the consequence of being Jewish, the happenstance he could do nothing about?

And why was this detail from the frescoes, of the horned devil carrying a maiden on his back, the one of which Freud bought an engraving that he kept for the rest of his life? (We know this because it remains in his personal archives, and has been published alongside the postcards from Orvieto.) He also bought a photo of the overall view of the town perched on a hilltop—a typical tourist’s souvenir. But of the art, what most fascinated him was this dramatic rape.

The questions fall furiously one on top of the other, the way the naked characters do. They are as raw as all this violent action, and as relentless. Did Freud imagine Signorelli’s scene as his own inferno, or at least the one he deserved, the way I do? Did he, like me, suffer from some inexplicable guilt and the burning feeling of having made dire mistakes? Can I try to understand his experience of Orvieto without imposing my own? How dare I look more at the paintings than at Freud’s own persona, of which I know little more than what the Karpes have described? If Christianity says that the original sin is the reason man became mortal, and Freud singled out Oedipal and Electra attraction as the source of melancholy, was it not the confrontation with all these issues, whether their manifestation in the Cappella Nova is direct or oblique, that forced him to forget a name? As for me, I cannot help but think that one’s feelings about one’s father, one’s mother, and one’s self is why Signorelli’s Inferno seems at times to represent not just my fate but my own mind.