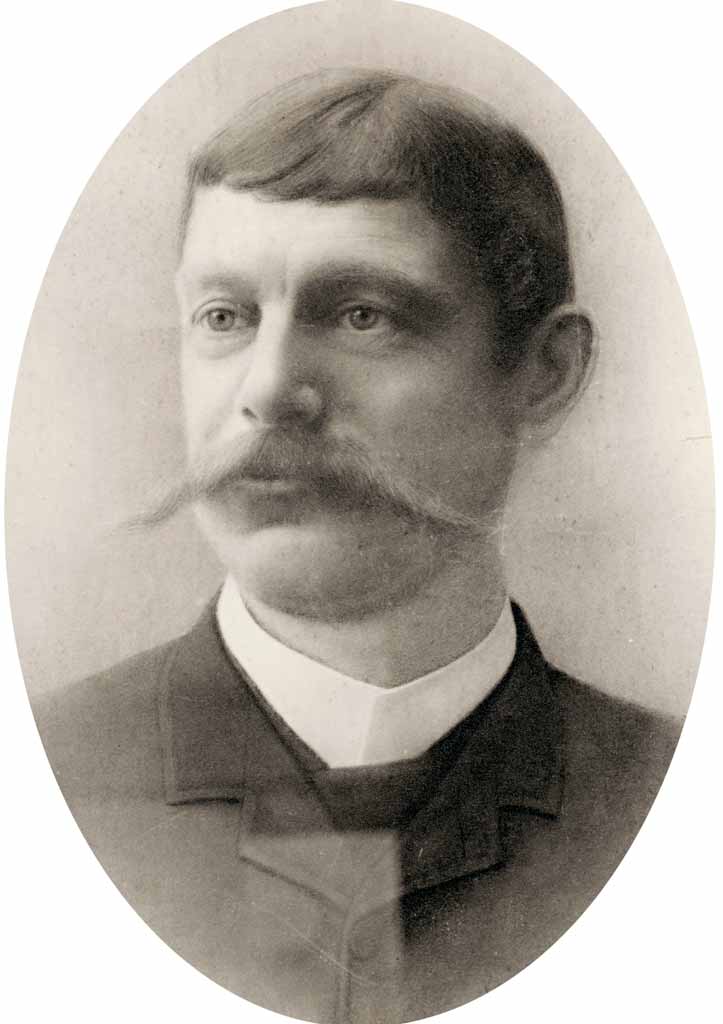

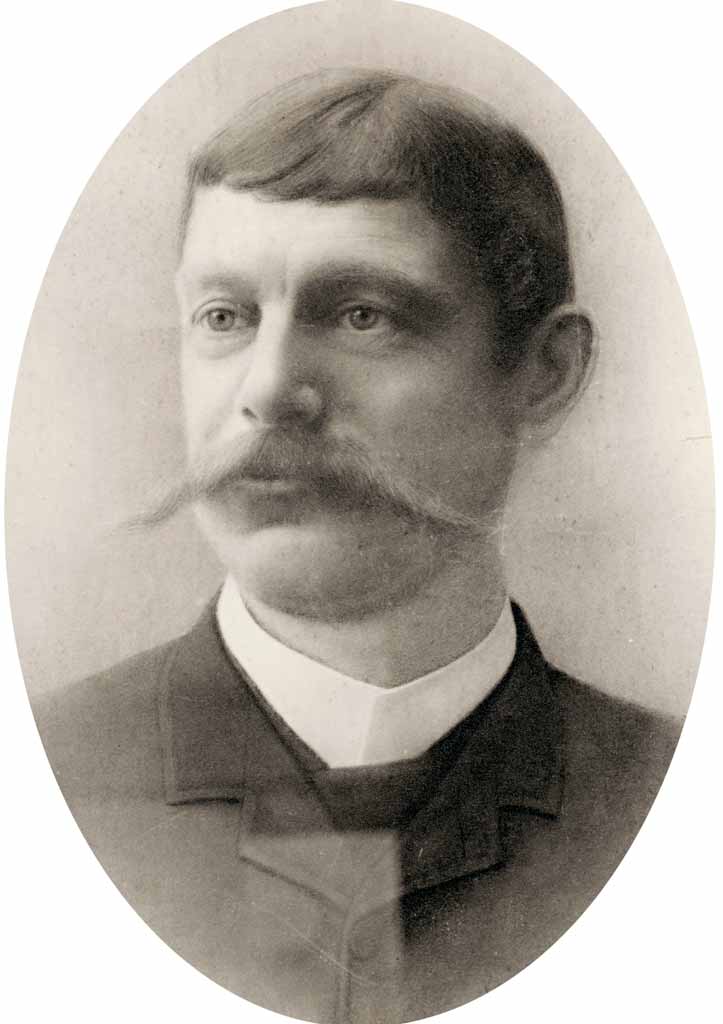

Van Kaspelen, Portrait of Neville Cayley 1892

A publicity photograph of Neville Henry Cayley when he was about 38 years old, organised by his long-term agent, art gallery owner William Aldenhoven.

NEVILLE HENRY

CAYLEY

Van Kaspelen, Portrait of Neville Cayley 1892

A publicity photograph of Neville Henry Cayley when he was about 38 years old, organised by his long-term agent, art gallery owner William Aldenhoven.

On 20 September 1877 two brothers disembarked at Hobsons Bay, Melbourne, on the clipper Sir Walter Raleigh, after a 90-day voyage from London. They had used their second names, and their ages, 21 and 23, were reversed in the passenger list. Nevertheless, the weight of evidence indicates that these new arrivals to Australia were Neville Henry Penniston Caley and his brother William Herbert Stillingfleet Caley.

The brothers are registered in the baptismal records of St Stephens Church in Norwich, in the county of Norfolk, England. Their parents were Nathaniel Henry Caley (1824–1867) and Berkshire-born Emily Dunn (c. 1830–1900), who married in February 1850. Nathaniel was the son of John Caley, silk mercer, and Emily was the daughter of Richard Penniston Dunn, auctioneer. Over the next 12 years, the couple produced eight children—four boys and four girls. Neville, the eldest son, was born on 29 May 1854, and William, the second son, 19 months later, in 1855. When the children were baptised, Nathaniel gave his occupation as ‘gentleman’.

Charles Nettleton, Hobson's Bay Railway Pier, Melbourne 1878

In September 1877, Neville Henry Cayley and his brother arrived from London at Hobsons Bay. The bay was the main port for Melbourne and was connected to the city centre by rail.

He was a silk mercer—recorded as ‘Silkman’ in the United Kingdom censuses of the time. The 1861 census notes that the family of two adults and seven children, aged between ten years and five months, shared an address with five females—four adults and one 16-year-old, presumably household staff. In 1863 Nathaniel was commissioned as an ensign in the 1st Norfolk Rifle Volunteer Corps, and he was promoted to lieutenant the same year.

Norwich, the second-largest city in England, has a long association with the manufacture of chocolate, a reputation that arose from a confectionary business started by Nathaniel’s brother, chemist Albert Jarman Caley. Nathaniel’s sons, however, began training in the same business as their father, as drapers. In the United Kingdom census of early 1871, father Nathaniel was described as a Norwich mercer. Neville, aged 16, was working as an assistant draper in Ipswich and William, 15, was apprenticed to a draper in Cambridge.

Court records in the United Kingdom’s national archives and elsewhere suggest that in departing for Australia Neville and William might have been escaping a family feud over their father’s estate, valued at a handsome 35,000 pounds. There is also a record in January 1875 of a William Caley of Norwich being found guilty of three cases of embezzlement for which he received a sentence of nine months imprisonment. For whatever reason, the two brothers emigrated and soon altered their surname, minimally, to Cayley—a more phonetically transparent spelling.

Little is known of the brothers’ first years in the Colony of Victoria. In Melbourne, they would have found a stately city, wealthy from gold and wool, where energy and enterprise thrived. The month after their arrival, Holmes, White and Co., a large trader of agricultural products and shipping agent for the Sir Walter Raleigh, was trying to contact them via an advertisement in The Argus: ‘CAYLEY BROTHERS, passengers Sir Walter Raleigh, would oblige by communicating with Holmes, White, and Co.’. Had ‘Herbert’ and ‘Henry’ jumped ship without settling their account?

William Cayley eventually became a clerk and accountant, with homes in Melbourne, latterly at South Yarra, then St Kilda and Balaclava. In 1887, he married Mary Maude Tyler (1868–1916) and they had five girls, losing one in infancy. As for Neville, he seems to have had a background in art, or at least some talent for it, for in April 1879 a notice in The Argus indicates that he was already working as an artist. ‘CAYLEY, Mr NEVILLE, artist,’ it read. ‘Please communicate with L. Hyman, Swanston-street, artists’ colourman. Important.’

As a child, Cayley would have taken drawing classes, then a compulsory subject for schoolchildren across England. He may well have been exposed to fine art, for his home town was the birthplace of the famous Norwich art movement, inspired by the natural beauty of the local landscape, and an art college was founded there in 1845. Perhaps Cayley saw or even engaged in silk painting at his father’s business. Norwich also boasted a museum and natural history society, while Cayley’s interest in nature may well have come from hunting and fishing trips to the countryside surrounding the city.

In Victoria, Cayley is supposed to have started his painting career in the Drouin area, in Gippsland, 100 kilometres to Melbourne’s east. He is also said to have spent time (perhaps earlier) in Hamilton, to Melbourne’s west. He achieved some recognition as early as 1880, when an advertisement in The Argus announced an auction in Collins Street, Melbourne, of some of his paintings, among a ‘small but choice’ collection of oils and watercolours by various ‘first class artists’, including John Glover.

It also seems that he had become something of the wild colonial boy, developing a reputation for his drinking habits, which were to lead him into debt. In January 1880, he was in the courts for default of payments. The case against him was for seven shillings and sixpence, plus five shillings costs, for goods from James Biram, storekeeper and spirit merchant, and he was found liable. He and William were then living in Warragul, near Drouin, where William was in the local cricket eleven. In May 1880, their two brothers Ernest Hugh and Arthur Pelham Caley, then 21 and 19, arrived in Melbourne on the Orient, but both returned to London separately later the same year. Their stay was brief for the times. Perhaps they had made the long journey to try to convince their brothers to return home.

Cayley too decided it was time to leave Warragul, but not for England. In December 1880, he had again been in the courts for default of payments. This time he had been ordered to repay the substantial sum of seven guineas to George Streitberg, publican of the Railroad Hotel, in weekly instalments of two pounds.

Apparently, Cayley took a ship very soon after to Sydney: possibly he sailed on the Omeo, which departed Melbourne on 10 December 1880, a week after the second hearing (an M. Cayley was listed as a passenger). Advertisements for Cayley’s artwork suddenly shifted into the New South Wales press. The Sydney Morning Herald of January 1881 reported that on display at the establishment of Mr Clarke, picture dealer of Pitt Street, were:

a couple of water-colour paintings from the brush of Mr. Neville Cayley, both of which are admirable representations of Australian birds. In the first, ‘A Bush Lecture,’ a couple of sulphur-crested cockatoos are perched on a bough, above a sea of tree tops. Monsieur, with his beak open, his crest up, and his feathers ruffled, is evidently administering a sharp curtain lecture to Madame, whose upturned eyes and deprecating attitude show that she has no defence to make. The figures are full of life, the treatment of the foliage is delicate, and the colouring is true, so that the picture is altogether a piquant little study. The second painting, ‘The Shepherd’s Clock,’ is of still higher merit, though less work has, perhaps, been put into it. It represents a couple of kookaburras—laughing jackasses— settled for the night on a leafless bough, one of them giving vent to the laugh which has scared so many strangers making their first journey through the bush.

In July and August 1881 Cayley stayed in Grafton, on the Clarence River, to do some illustrations for the local museum and to seek commissions. To demonstrate his skill he showed paintings of a pair of kookaburras, Black Ducks on a lake and a blood horse. By the end of his month’s stay he had completed portraits of a favourite buggy mare and a homestead.

That October, The Sydney Morning Herald reported, Cayley exhibited some noteworthy paintings in the second annual exhibition of the Art Society of New South Wales: ‘a dead canary hanging against a panel … of its kind, a gem’ and ‘blue wrens … an exquisitely finished bit, which proves that this artist’s forte lies in the delineation of birds’.

The canary must have sparked memories for Cayley. His home town of Norwich had long been renowned for its large canaries and in the 1870s there were thousands of canary breeders in the area. Across England, many shops, factories and homes kept the singing cagebirds. It seems likely that Cayley would have attended the British National Cagebird Show of 1873, held in Norwich, which attracted a huge crowd. The exhibits of a local breeder, Edward Bemrose, caused a sensation. His canaries were luminous orange, the colour of marigolds. Bemrose claimed that he had developed the birds through selective breeding. There were skeptics and not without reason—purchasers of the songsters found that the birds’ colour faded after the autumn moult. Yet the birds had not been dyed.

By the end of the year an employee had sold Bemrose’s secret for 50 pounds. Bemrose came clean, publishing an article entitled ‘How to Obtain High-coloured Canaries’ in the December issue of The Journal of Horticulture and Cottage Gardener, revealing that he had fed the birds red peppers. ‘Colour feeding’ was briefly regarded as cheating, but soon everyone was doing it to improve the fancy. Although it was not realised at the time, Bemrose’s discovery was early evidence that nurture, as well as nature (genetics), had a role to play in the expression of characteristics such as colour.

Canaries aside, just a few years after immigrating to Australia, not only was Cayley working as an artist but he was also beginning to find his niche, as a ‘delineator’ of birds. More than that, he was soon creating his distinctive paintings of kookaburras, blue wrens and dead and dying game birds. Together with his tongue-in-cheek Australiana, they were to become his signature works.

In 1882 The Sydney Morning Herald reported that Cayley had painted another characteristic work, of a kookaburra grasping prey in its beak— in this case a ‘writhing centipede … the burnish of the insect’s scaly joints … painted with no less accuracy than the delicately tinted plumage of his captor’. A second watercolour featured ‘a falcon perched on a rocky point beside a lake … holding in one of its talons a dead robin’. Both works were on sale at Nicholson and Co., music publishers of George Street, Sydney, and, the reporter averred, Australian birds had ‘certainly never had a better delineator’.

Along with these more violent, realistic works— Nature, red in tooth and claw—Cayley was also producing pretty, even sentimental, images. For a Mrs Meillon, he painted on silk a fairy-wren flying among flowers, which was displayed at the 1882 horticultural and flower show and fine art exhibition of the Clarence Pastoral and Agricultural Society (CPAS).

From 1881 Cayley was on the Clarence River, at Grafton, Chatsworth and Yamba. The area was known for its majestic waterway, magnificent tall forests, mild climate and rich diversity of wildlife, especially waterbirds and fish. Perhaps significantly for an artist seeking commissions, there was also wealth from grazing, gold and from logging of ‘red gold’ (red cedar). Moreover, Cayley was distant from the competitive, established artists of Sydney.

Neville Henry Cayley, Yamba Township 1886

After his marriage to Lois in 1885, Cayley returned to Yamba on the Clarence River. In 1886 their son Neville William Cayley was born and, in the same year, Cayley made this sketch of the growing town from a jetty looking across Yamba Bay. It hung in the local Wooli Hotel (shown behind the right-hand yacht) where he had stayed as a bachelor.

A number of collectors operated in the region, supplying Sydney and beyond with bird skins and eggs. James Fowler Wilcox was one such dealer, but he died in July 1881 and Cayley may not have had the chance to meet him. George Savidge was the best-known local ornithological collector. Just five years younger than Cayley, Savidge first managed, then owned, a store at Copmanhurst on the upper Clarence River from about 1883, and was a fine photographer. The two men would have had much in common, including cricket.

Cayley boarded at the Wooli Hotel near the wharf at Clarence Heads (Yamba, the town, was not proclaimed until 1885), where the river meets the sea. There he had easy access to Sydney, 300 miles south via coastal steamer, and to Grafton, the region’s commercial centre, 45 miles upriver past the pretty towns of Maclean and Rocky Mouth. To some, it may have looked as if Cayley had distanced himself from the city, but the Northern Rivers district, centred on Grafton, offered a fine civic and cultural life.

The Wooli Hotel, owned by the congenial Walter and Maria Black, was the first hotel at the site of Yamba and the social centre of the town. The neat eight-room inn had a steep shingle roof, attic rooms and a spacious verandah overlooking the sheltered bay. The Black family recalled that Cayley sometimes paid his hotel bills with paintings. Cayley was taking commissions, among them one for a portrait of Emma Pegus— the local postmistress and sister of Maria Black. Cayley painted her likeness on glass from a photograph. He was possibly influenced by the works of Conrad Wagner, who created his posthumous portraits—that is, portraits painted after their subject had died—by enlarging and painting over photographs. Wagner was a scene painter and photographer known internationally for his portraits of the local Aboriginal people. Previously Grafton’s resident artist, Wagner was then living a steamer ride upriver at Glen Innes, on the overland route from Grafton to Sydney.

Wagner was a friend of sometime Grafton resident, celebrated poet Henry Kendall, who Cayley may have later met through their shared love of birds and song. Kendall had a turbulent private life but became a significant figure on the literary scene. He composed some of the earliest poetry about Australian birds, in 1862 penning The Curlew Song, in which he wrote: ‘They rend the air, like cries of despair, The screams of the wild Curlew!’. By the time Cayley arrived at the Clarence River, Kendall was long gone, but the river remained a source of inspiration for Kendall’s poetry and he was much celebrated in the region. An opportunity for their meeting was likely when Kendall, who had a deep knowledge of timber, toured the Clarence in August 1882 as the newly appointed inspector of forests; he died later that year when still in his early forties.

On the Clarence, Cayley had still not settled on a style or genre. As well as birds, he was drawing landscapes of the picturesque bays and breakwalls. One of his sketching partners was Edwin James Cox, the local blacksmith, who had received some tuition in painting oils from Wagner. Cayley also went camping and sketching along the Clarence River with James O. Burgess, a surveyor at Grafton, watercolourist, supporter of the local school of art and judge at the Clarence Pastoral and Agricultural Society (CPAS) flower shows and fine art exhibitions in which Cayley and Cox took part. In one of his sketchbooks, Burgess kept a pencil drawing by Cayley, captioned Shifting Camp on the Clarence River NSW from Maclean to Wombah, 1882. Cayley drew himself lounging in the stern of a dinghy while his companions relaxed among their closely stowed gear.

Neville Henry Cayley, Shifting Camp on the Clarence River NSW from Maclean to Wombah 1882

From the time he arrived in Australia Cayley seems to have tried to establish himself as a professional artist. He often sketched in the bush. In 1882, Cayley and his friends took a dinghy and, heading downriver, camped along the beautiful Clarence River. Between Maclean and Wombah (now Woombah), Cayley made a playful drawing of the relaxed crew in the sketchbook of surveyor James Burgess.

Neville Henry Cayley, The Wreck of the SS New England on the Clarence River Bar 1883

In December 1882, lodging near the mouth of the Clarence River in northern New South Wales, Cayley was on hand to sketch the wrecking of the SS New England, one of the steamers that linked the district with Sydney. His sketch was converted into this woodcut for The Illustrated Sydney News.

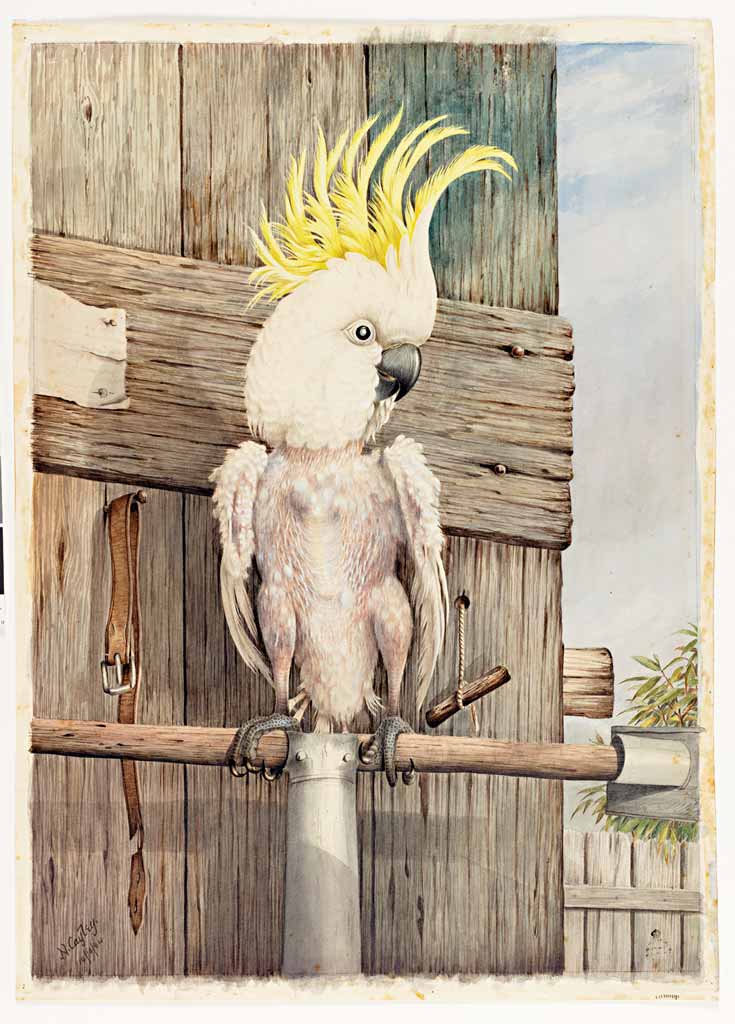

Neville Henry Cayley, Crested White Cockatoo 1884

When this 1884 painting of an aged or ailing captive Sulphur-crested Cockatoo was put on show in the window of Nicholson and Co., the unusual subject matter attracted considerable attention in the press.

In December 1882 the New England, a coastal steamer plying the Grafton-to-Sydney route, foundered on the bar in the river and was quickly wrecked by the waves. Descending darkness hampered the rescue crews and the captain and about five crew and four passengers drowned. The Illustrated Sydney News reported that ‘Mr Cayley residing a few miles from the scene of the disaster’ made a sketch, reproduced in the newspaper as a woodcut. In February the local paper, the Clarence and Richmond Examiner and New England Advertiser, reported that he had:

commenced a water colour painting, depicting the principal incidents in this memorable disaster. We believe the artist will probably have the picture lithographed, and in that form it should have a good sale, as almost everyone would like to have such a memento of this event.

Possibly few fancied a reminder of the tragedy, for the print seems not to have eventuated. Cayley had greater success with his paintings of birds. The local paper reported that at the April 1883 CPAS show Cayley’s watercolours—of a magpie with young and a hawk killing a parrot—were ‘much admired’. He was enough of a local celebrity for the Grafton correspondent of The Sydney Morning Herald to include among other local news that ‘Mr. Neville Cayley, an artist, had the misfortune to get his arm broken, by a fall from his horse at Rockymouth, this week’.

At the next year’s CPAS exhibition, Cayley’s portrait of a sheepdog was described in the local paper as ‘good’ and he won second prize in the watercolour landscape section for a work entitled Clarence River. Perhaps Cayley’s more modest results when he strayed from birds made him aware of his shortcomings, for by late 1884 he was back in Sydney, living at Wentworth Court and attending art classes.

Nicholson and Company Music Store, Sydney c. 1905

During the early 1880s, Nicholson and Co. of George Street, Sydney, music dealers and occasional purveyors of art, provided Cayley with an outlet for his paintings.

That November, Cayley drew a great deal of attention for his unusual artwork on view at Nicholson and Co.; The Sydney Morning Herald picked up on the ‘very interesting water-colour’, and the story was repeated in several other broadsheets. Cayley had painted what was thought to be an elderly cockatoo:

It represents probably the oldest tame cockatoo in Australia … Its exact age is not known, but it has been 80 years a pet of the Wentworth family before 1872, when Mr. Hill became its owner, so that it must now be almost a centenarian. It is remarkably intelligent, and talks fluently, and more rationally than such birds usually do; but its appearance is very grotesque, because it is nearly blind from cataract, and almost entirely featherless. It objects to plumage, and from the neck downwards has deliberately plucked out all but about half a dozen wing and tail pen feathers whereas its head is covered with a dense white crop, and crowned with a magnificent sulphur-coloured crest. The odd colors of the flesh tints, and the scraps of plumage which occasionally contrast with them, are difficult of reproduction; but Mr. Cayley has succeeded admirably in overcoming all difficulties, and has painted a perfect portrait and a very fine picture.

In fact, the cockatoo may not have been ancient at all, or at least its grotesque appearance may not have been due to age. Quite possibly it was suffering from beak and feather disease, now known to be caused by a virus that attacks the feather follicles and growing cells of the beak and claws, causing their loss and malformation.

In February 1885 Cayley left another bird painting for sale with Nicholson and Co., a ‘small swamp hawk stooping to strike one of three wild ducks’, painted near Clarence Heads. According to The Sydney Morning Herald, ‘the birds are, as usual, perfectly drawn and coloured, and the contrast between the flutter of the hawk and the impulsive flight of his prey is very well defined’. Cayley also had several works in the Art Society of New South Wales’ sixth annual exhibition. A critic for The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser thought they were not his best, but that:

Mr. Neville Cayley has a field all of his own in the painting of Australian birds. He has painted better birds than he shows here; but he never paints birds otherwise than well, and might well be put in commission by those who have charge of the youth of the colony, to supply them with fair copies of all the charming feathered creatures they only want to destroy.

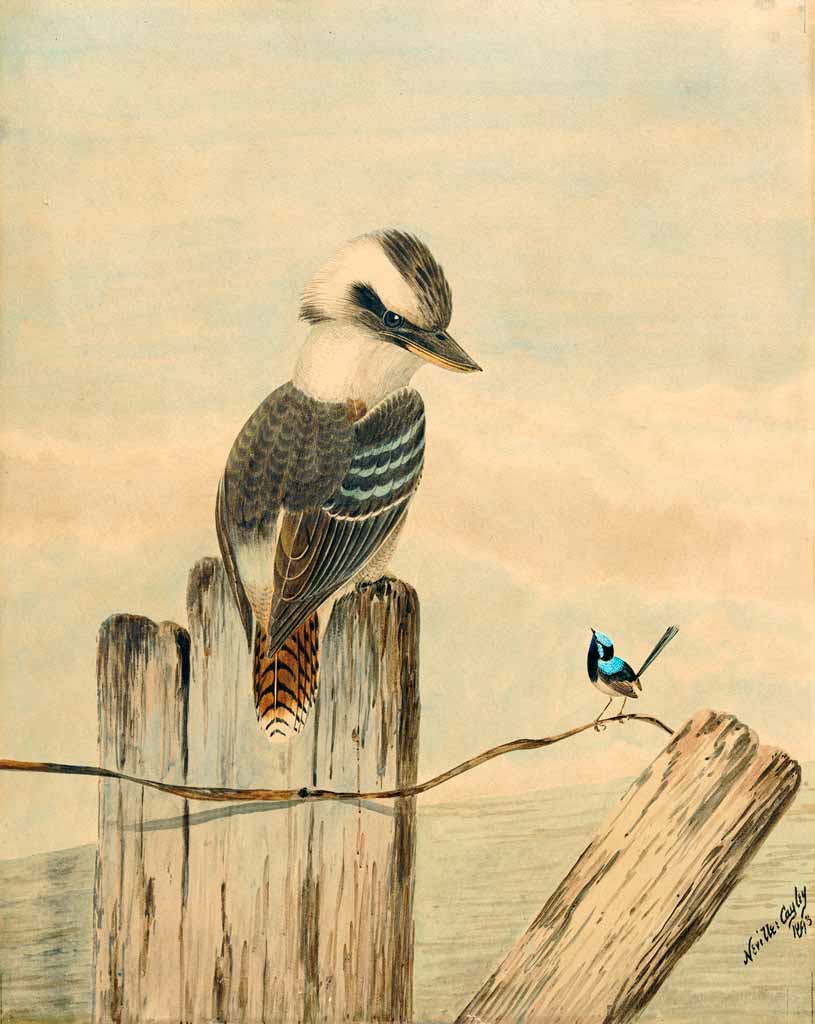

The move to the Colony of New South Wales had proved wise and Cayley’s reputation was growing. Residents of the Australian colonies were generally comfortably off and, with the push for federation, national pride was growing. It was becoming popular to hang decorative portraits of iconic wildlife on the walls of homes and businesses. They could be talking points, especially when given the humorous titles Cayley assigned his work. Dignity and Impudence—a cheeky fairy-wren confronting a kookaburra—and Bone of Contention—magpies squabbling over a bone—were two such paintings, exhibited in the 1885 Art Society exhibition. Hunting was a popular pastime and Cayley’s ‘trophy’ paintings of game were much admired: a brace of ducks curing on a hook or various fleeing snipe, quail and ducks captured in flight at the moment they were shot. The Cruel Divorce (see a version of this on page 69)—a pair of Latham's Snipe suspended in midair, one mortally wounded—catered to both markets.

Still, Cayley wished to improve his skills, particularly in landscape painting. He enrolled in classes, perhaps with Alfred Daplyn, an exponent of plein-air painting and in 1885 the first paid instructor at the Art Society of New South Wales’ school in Pitt Street. The Clarence and Richmond Examiner and New England Advertiser of July 1885, proud of their local artist, had the news that Cayley was considering a return to the Clarence to teach art. In the meantime, he had:

been studying perspective and landscape sketching, with the determination to excel in this branch of his art as he is universally admitted to have done in birds, flower painting, &c.

Despite the advantages of the city, Cayley’s heart was not in Sydney. He liked the bush and, back on the Clarence, he had been courting Grafton girl Lois Emmeline Gregory (1863–1941), daughter of William and Adelaide Gregory, who owned several stores in the Clarence River area. He may have met Lois in Grafton or when the family visited Yamba. The coastal town was a popular holiday spot for the region and Lois’ mother held the lease on the Ocean View Boarding House overlooking the main beach at Yamba from 1879 until 1884. They were married in Sydney in 1885; Cayley was 31 and Lois was nine years his junior. Later that year they set up home at Yamba.

Neville Henry Cayley, Dignity and Impudence 1893

Dignity and Impudence was Cayley’s gently comical take on the Laughing Kookaburra and Superb Fairy-wren, two of Australia’s favourite birds. Cayley first exhibited a version of the painting in 1885 at an Art Society of New South Wales show.

Cayley now had a wife to support. In November and December 1885 he placed advertisements in the Grafton newspaper:

PERSONS desirous of taking LESSONS IN WATER COLOUR PAINTING under the tuition of MR NEVILLE CAYLEY, may have an opportunity of doing so, if sufficient inducement offers. The terms will be £3 3s per quarter, payable in advance. Names of those wishing for lessons to be left at the EXAMINER office.

Neville Henry Cayley, Delias aganippe (Wood White or Red-spotted Jezebel), New South Wales 1887

Neville Henry Cayley, Chaerocampa erotus (Hawk Moth, now Gnathothlibus erotus), Sydney 1887

In 1887 and 1888 Cayley was engaged to paint butterflies and moths for a scientific publication planned by the Australian Museum in Sydney. The publication never appeared, but in other works Cayley used butterflies and other insects to help animate his bird portraits and as a decorative feature.

He attracted at least a few students, among them Walter Thomas Stevenson, and, possibly, Edwin Cox. Stevenson later opened a photographic studio in Grafton, published the photographic book Picturesque Clarence (1900), and exhibited the occasional watercolour in the local flower and fine art exhibitions. It seems that Cayley had a strong influence. A September 1909 edition of The Clarence and Richmond Examiner reported that:

Mr. W. Stevenson, who studied under Cayley, has just completed a fine water colour of a wild duck in the act of falling as the result of a shot.

At Kookaburra Cottage, Yamba, on the seventh day of 1886, the Cayleys’ first child was born. They named him Neville William Cayley— after Lois’ father and Cayley’s brother. Among Cayley’s landscapes that year was one of Yamba Bay (see image); the work was to hang in Walter Black’s Wooli Hotel. Cayley painted it from the jetty at the inland end of the bay, looking across to Yamba Hill with its flagstaffs and budding township. The new passenger steamer Iolanthe is in the middle ground. Behind, at left, is the wreck of the Mary Ballantyne and, at right, the government steamer Princess, docked at the Yamba wharf in front of the Wooli Hotel. The newer Yamba Hotel stands at far right.

That year Cayley found some employment painting illuminated addresses. The addresses were a popular presentation gift at the retirement or departure of a prominent person. They usually included some sort of testimonial and were ‘illuminated’ with borders of handpainted native flora and fauna or some other appropriate ornamentation. Cayley, the local paper noted, had decorated one for a retiring magistrate thus:

Bright plumaged diminutive birds and beautiful hued butterflies are interspersed in the address with good effect, while in the borders and trailing around and between the views are sugar cane, the magnificent blue waterlilies of our creeks, and native orchids, with flowers and grasses, the whole having a very beautiful effect. It was also surmounted with the Royal Arms, very carefully drawn and coloured.

With a family to support, Cayley was also trying to capitalise on his growing fame, or perhaps simply attempting to make a living, through an art union. In mid-1886, 20 paintings and five handpainted satin aprons were offered as prizes in the Cayley’s Art Union, to be drawn at the start of February 1887. At half a sovereign, tickets were promoted as a bargain, for, it was claimed in the local newspaper, Cayley’s paintings had sold for upwards of 100 sovereigns, ‘realising at times high prices wherever they particularly suited the tastes of buyers’. The advertisers gave the assurance that ‘In bird painting Mr. Cayley stands alone in the colonies, and anything from his hand which depicts birds of any kind may be valued as a work of art’. Curiously, their views on Cayley’s two landscapes were unlikely to inspire buyers:

Landscape is not the artist’s forte, but he has here succeeded in producing a good picture, with tints harmoniously blended, and the woodland well worked in: altogether a picture no one need be ashamed to hang in his drawing-room … The views of the Clarence Heads by moonlight … we do not care so much for.

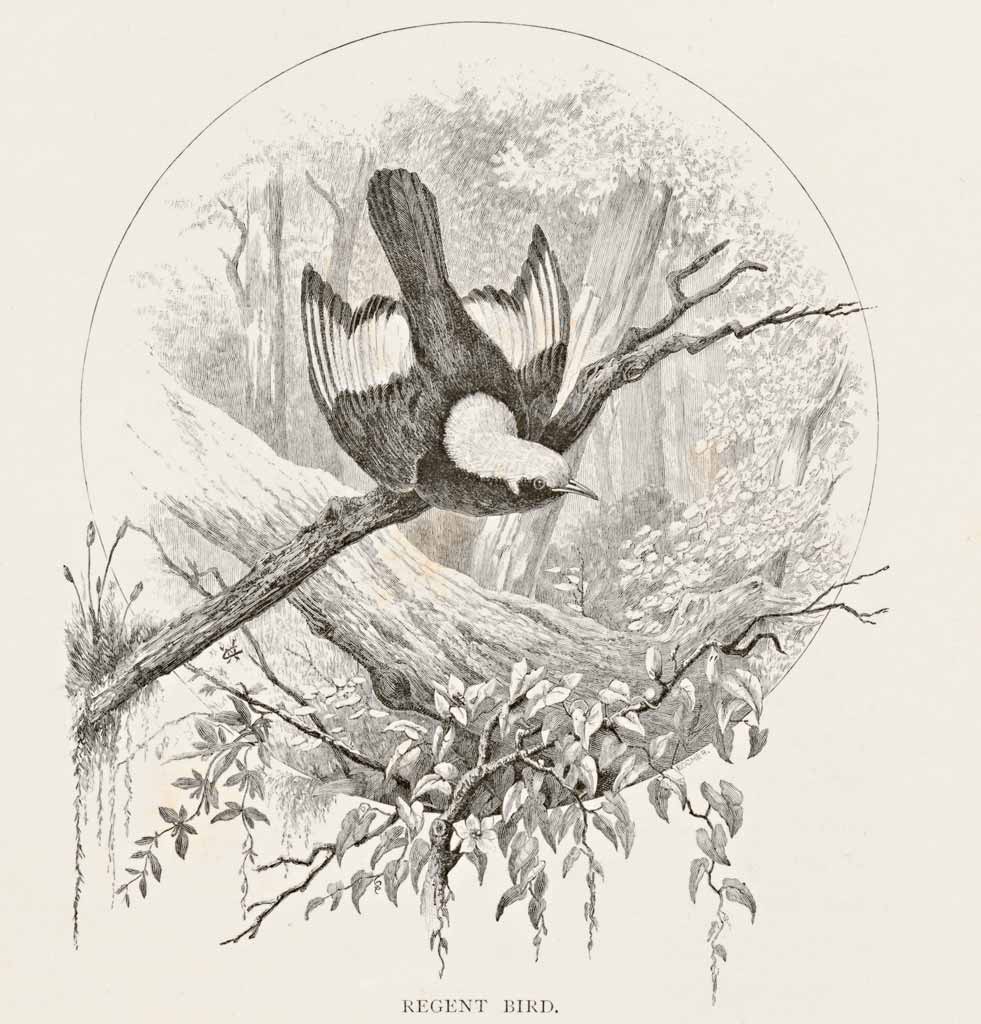

Neville Henry Cayley, Regent Bird 1886

In late 1885 Cayley was commissioned to draw birds for the ambitious publication The Picturesque Atlas of Australasia. The income would have been welcome, as would have been the opportunity to work with some of the finest Australian artists and engravers of the day using state-of-the-art printing processes.

As well as painting birds and the local landscape, Cayley was involving himself in the local sporting scene. In 1886, at Easter, he was on the organising committee, with his friend William Black, for the annual Yamba regatta. In November he was involved in the military games held at Grafton racecourse by the Ulmarra and Grafton Light Horse and Grafton Infantry (troops of the New South Wales Northern Rivers Lancers) in celebration of the birthday of the Prince of Wales. It seems that Cayley had signed on to the short-lived local chapter of the (mounted) New South Wales Volunteer Infantry. Events included wrestling on horseback, a bayonet exercise, tent-pegging, and ‘cleaving of the Turk’s head’! Cayley acquitted himself well, winning a special prize for the best man in the bayonet team.

At some stage the Lancers must have invested in some of Cayley’s art. Many years later, in 1933, as Australia was recovering from the Great Depression, it was disclosed in the annual report of the Lancers Association of New South Wales that:

the valuable pictures by the late Neville Cayley which were buried in a suburban haystack three or four years ago by a member for safe keeping had not been recovered. The pictures comprised sketches and paintings which were the property of the association.The paintings were still under tons of hay. Their recovery seemed practically impossible.

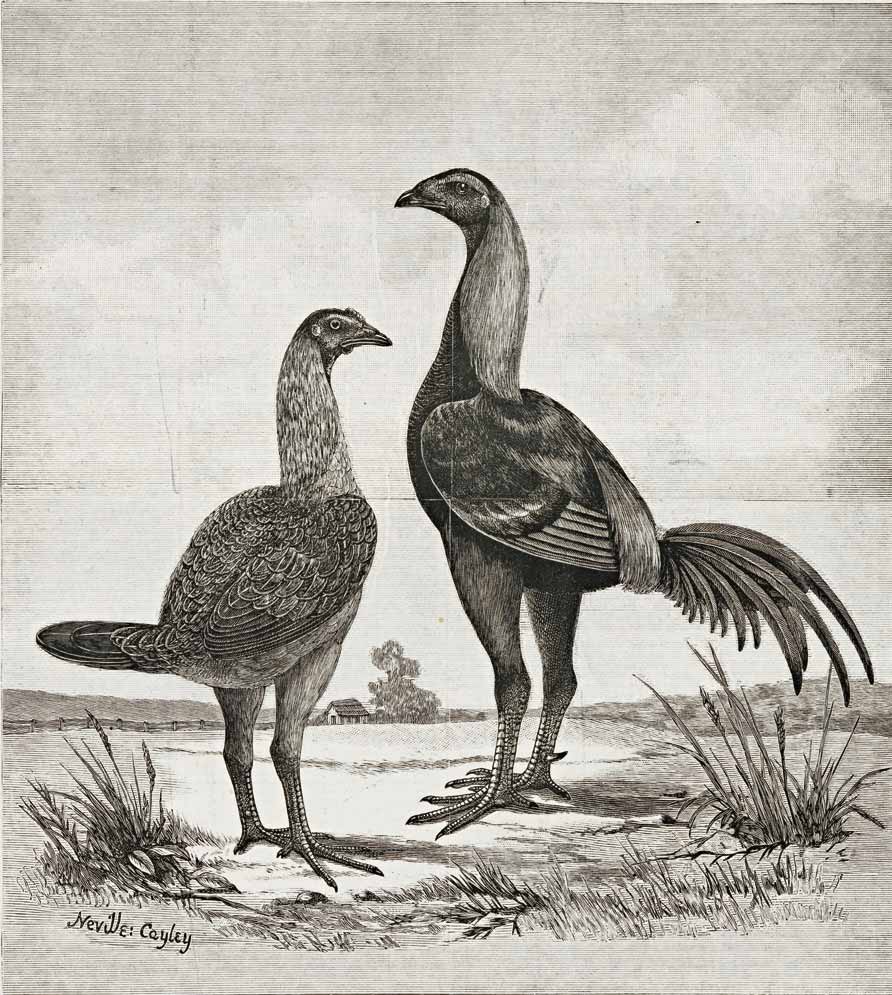

Neville Henry Cayley, Australian Game 1889

In 1889, the Cayleys were living in Bowral, and their second child, Alice, was born. Cayley raised several varieties of domestic chicken and drew this example to illustrate an article on the Australian Game Fowl for The Sydney Mail. The leggy chicken was a tall, muscular variety developed in New South Wales from fighting fowls as a table bird.

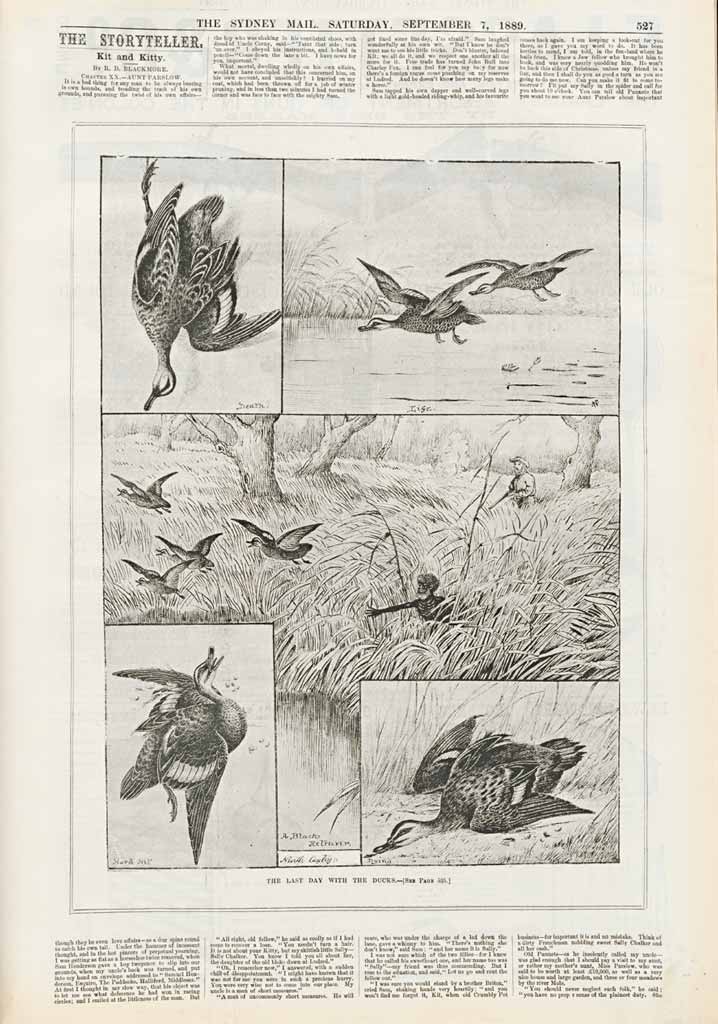

Neville Henry Cayley, The Last Day with the Ducks 1889

Cayley’s illustration for the announcement in The Sydney Mail of the end of the 1889 open season on waterfowl reveals his mischievous sense of humour.

It appears that Cayley’s art union was not a great success—a week out from closing ‘a good many tickets’ were still available, according to the local paper. However, things were looking up for Cayley by late 1886. William Aldenhoven, well-connected art dealer, picture framer and publisher of fine art, became his sole agent. Aldenhoven put on show in his Hunter Street gallery several framed paintings of birds ‘taken from nature’, including Regent Bowerbirds, Paradise Riflebirds, blue cranes (White-faced Herons) and diamond birds (Diamond Firetails). Aldenhoven’s advertorials claimed that Cayley’s paintings had attracted some attention at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London, that he was now living in Sydney again, and that ‘with his newly-won laurels, local connoisseurs will be glad to welcome from his studio these latest artistic productions’.

Amid the fanfare, Aldenhoven damned with faint praise the landscape work that Cayley had striven to improve:

The landscape—a river view with background of mountain scenery—is well worked out. In this branch of his art Mr. Cayley appears to have considerably improved, but it is in the bird study that the excellence of the work consists.

Thereafter, it seems, Cayley accepted the views of Aldenhoven and the critics, and the preferences of the public. He concentrated mainly on birds for the art market. The promotional skills of Aldenhoven were to make him a household name.

Meanwhile, in the final months of 1885, Cayley had been hired among other noteworthy artists such as Louis Buvelot, Tom Roberts, Julian Ashton and Ellis Rowan to illustrate The Picturesque Atlas of Australasia, an ambitious illustrated history of the Australian colonies intended to cash in on the centenary and to appeal to an overseas market. The publishers were also taking advantage of improved engraving techniques, developed in America, that produced a quality product in large quantities, making illustrated publications more economical.

Charles Bayliss, Pitt St, Sydney 1886

William Aldenhoven, Cayley’s sole agent, had a well-known gallery in Pitt Street, in central Sydney. This photograph of the street was taken in 1886, the year Cayley’s son Neville William was born. From this time until well after Cayley’s death in 1903 Aldenhoven did much to make Cayley a household name.

The project was a boon for struggling professional artists and Cayley contributed several portraits of birds. As an article in The Sydney Morning Herald in June 1886 explained, the drawings were done in black and white, then photographed onto wood:

Formerly the artist’s sketch was affixed to the wooden block upon which the engraver worked, gradually as his engraving proceeded destroying the original sketch. The new method has several advantages, not the least of which is that the original sketch is not interfered with, and can be referred to by the engraver during his work and compared with the engraving when the latter is finished. The taking of large black and white sketches enables the artist to deal with his subjects broadly, and the photographing refines and tones down what would otherwise be rough and bold.

Neville Henry Cayley, Eggs from 16 Species 1889

Explanation of plate VIII:

1. Smaller Rufous-breasted Thrush (now Rufous Shrike-thrush)

2–4. Harmonious Thrush (Grey Shrike-thrush)

5. Crested Wedge-bill (Chirruping Wedgebill)

6. Crested Oreoica (Crested Bellbird)

7. Coach-whip Bird (Eastern Whipbird)

8. Grey Struthidea (Apostlebird)

9. Frontal Shrike-tit (Crested Shrike-tit)

10. Gilbert’s Thickhead (Gilbert’s Whistler)

11. Olivaceous Thickhead (Olive Whistler)

12. Pied Grallina (Magpie-lark)

13. Black-faced Wood Swallow

14. Wood Swallow

15. Long-billed Bristle-bird (Western Bristlebird)

16. Bristle-bird (Eastern Bristlebird)

During the new process, patches of paper applied to the block were used to build up areas of light and shade. The block was then placed in position on the page, with text or a caption, and covered in wax applied under pressure. Next the wax impression was coated in lead and placed in an electrolyte bath until it was coated in copper and ready for the presses.

The three volumes of The Picturesque Atlas were first published in Sydney between 1886 and 1888. An army of persistent agents canvassing the colonies ensured that it sold an extraordinary 50,000 copies. However, the atlas fell from favour when the many who had prepurchased realised that they had signed up for an unspecified number of sections at five shillings apiece.

In 1887, living at Paddington, Sydney, Cayley began a project on moths and butterflies. The trustees of the Sydney (later Australian) Museum had decided to complete Australian Lepidoptera and Their Transformations Drawn from the Life. With descriptions by Alexander Walker Scott, and illustrations by his daughters Helena and Harriet, the first volume had been published in 1864. Now some of the Scott sisters’ beautiful, unpublished original plates had ‘fallen into the trustees’ hands’, as reported in The Sydney Morning Herald. During 1887 and 1888, 131 new plates were completed (some by Cayley— see, for example, page 16—but many by P.T. Hammond). However, that part of the project was abandoned, perhaps because of problems with the museum’s entomologist Arthur Sidney Olliff—he apparently had a fondness for spirits and was dismissed in about 1889. Nor was the artwork comparable to the Scotts’, and they may not have approved. Under Helena’s close guidance, and with Olliff’s collaboration, the museum finally published the second volume of the Lepidoptera in five parts between 1890 and 1898, using only the Scott sisters' illustrations.

Neville Henry Cayley, Black Duck c. 1896

This image of a Black Duck, hanging suspended midair at the moment it is shot, was Cayley’s best-known work, and the Art Gallery of New South Wales purchased the first version of it, painted in 1890. Cayley made several versions—variously titled Dues, Hard Hit and, perhaps coined by cataloguers, Shot Duck. The work spawned similar images of other hunted waterfowl, including snipe, godwits and Mountain Ducks.

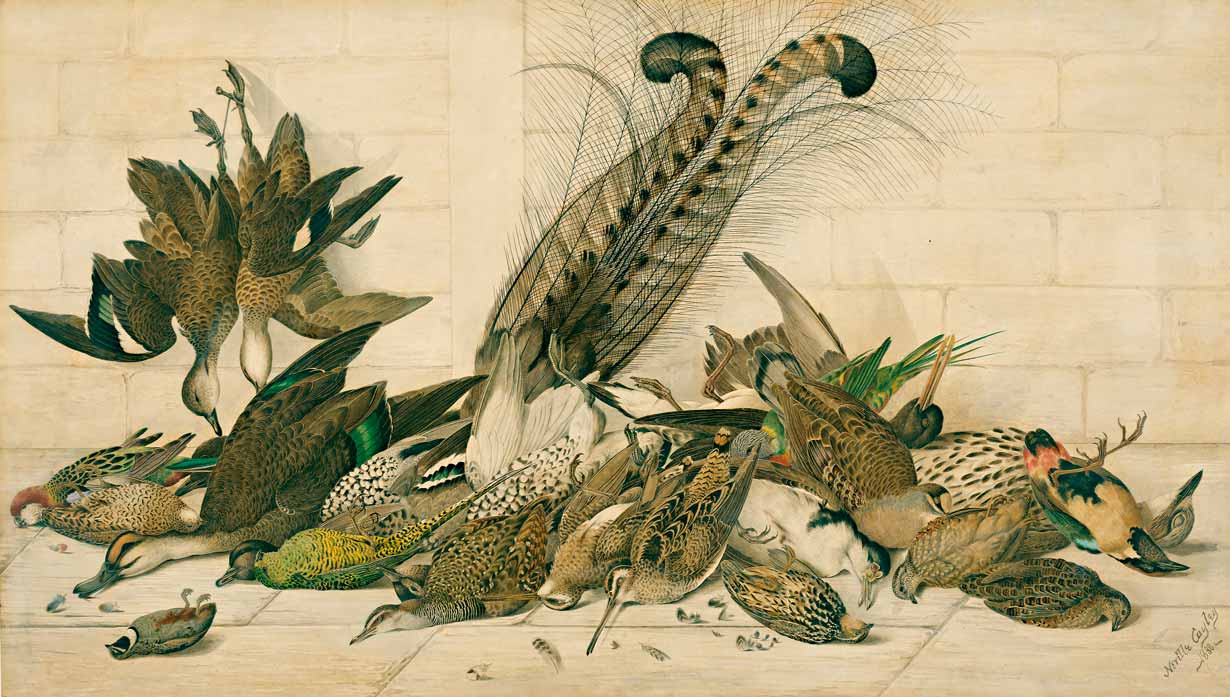

With professional management and promotion, Cayley became more widely known in the fine art sphere and over the next few years he began to produce some of his best work. In July 1888, as The Clarence and Richmond Examiner reported, Lady Carrington, wife of the Governor of New South Wales, visited Aldenhoven’s gallery to inspect Cayley’s paintings. She was able to view only a few because 77 had been sent to Melbourne by Aldenhoven to be hung in the New South Wales court of the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition of 1888 to 1889. There, Cayley’s watercolours may not have made a ‘big splash’, as was predicted by his barrackers at the Northern Rivers’ broadsheet, but he received a jury award for his collection, which included no less than six paintings of kookaburras, as well as illustrations of kingfishers, the works Shot Snipe and Hard Hit, Black Duck, and the whimsical Fight between a Canary and Blue Warbler. The first item in the catalogue, his pièce de résistance, was catalogued unattractively as Still-life (Dead Birds). It later came to be regarded as his masterpiece. Without irony, it was billed as being ‘painted from life’, a selling point often applied to his illustrations of birds, even though he painted from their skins.

In late 1888 Aldenhoven’s was also promoting a set of greeting cards—‘the prettiest novelty’, according to the advertisements—with a selection of Cayley’s bird illustrations. The next year, Christmas and New Year cards illustrated by Cayley (among the earliest published in Australia, by Turner and Henderson), 41 to choose from, were being marketed as ‘an excellent souvenir for friends abroad’ and ‘ready for dispatch to dear old England’.

During that period, from about January 1888, the Cayleys were living in the Bowral district. Cayley thought the cool, clean air of the Southern Highlands would be better for his health than Sydney, three hours away by rail. Indeed, the area was a popular Sydney retreat, especially in the summer months. The Cayleys first moved to Moss Vale, where in February he convinced a Mr A. Salmon to show two watercolours in his store window. The local paper, The Scrutineer, described one of them thus:

The duck represented is being mortally wounded through the left breast and wing, and in the last struggle of death’s agony … the figure and outline and toning are exceedingly well done, and form altogether a nice ideal study, and a prettily-finished picture.

The prettily dying duck is possibly the first version of Cayley’s slightly surreal, best known and most popular work (often called Hard Hit). The other painting also stirred up some flowery rhetoric that played on the prevailing view that kookaburras were useful (and therefore were not to be shot—unlike some other, presumably useless, birds):

the brilliant sparkle of the eye depicts the delight and satisfaction the snake-destroying kookaburra feels in his successful capture … which he holds with a firm grip in his strong bill … about two inches from the head, the tail of the venomous reptile lying limp across the dead limb, on which he sits with safety and complacency; the head feathers of the kookaburra stand electrified half erect, the glare of the eyes and the inflated form of the body, assist in marking the triumph over a most deadly foe.

Cayley obviously painted quickly, for, the article claimed, the two works had been executed the previous week. The report went on to say that Cayley had sought ‘the scenery and climate of Moss Vale for his future field of labor’. He had already obtained some orders for ‘elaborate painting’ and would ‘no doubt, receive sufficient patronage to make his stay sufficiently long to recruit his health’.

Neville Henry Cayley, Bird of Paradise (Paradisornis rudolphi), a Native of New Guinea (now Blue Bird of Paradise, Paradisaea rudolphi) c. 1892

In the late nineteenth century, New Guinea was still yielding up birds of paradise to European scientists who went in search of new species or to rediscover birds known only from skins traded many years before. The birds’ fanciful shapes, eccentric behaviours and fabulous plumes enchanted the public, some of whom wanted the feathers for their hats. In 1889 Cayley offered to paint the rare, recently discovered Blue Bird of Paradise for the Australian Museum.

Later in the year Cayley completed two commissions for The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. The first, published on 7 September 1889, accompanied a brief article flagging the beginning of the ‘close season’ (the closed season, which ran from the beginning of September to the end of February). It reminded readers that in 1881 the colony had passed an Act to prevent the destruction of certain native birds during the breeding season, with penalties of up to five pounds for breaches. Cayley, it noted, ‘has given us an excellent picture which will recall to the mind of the sportsman many a pleasant outing with the gun’. His five vignettes of a Black Duck (see page 19) were titled Life, Hard Hit, Dying, Death and Black Retriever.

The Sydney Mail of the following week, 14 September, ran an illustration for the poultry fanciers of the colony (see page 19). It showed the cock and hen of a strain that had been developed in New South Wales. The making of the illustration was guided by advice from leading judges of the breed:

Weeks have been spent in the drawing. Several sketches made from life were the foundation of the work. Next came the suggestions of judges, the material by which existing faults could be corrected; and last stage of all was the patient, skilful work of the engraver. The result, we are pleased to say, bears comparison with the best of European poultry portraiture.

Neville Henry Cayley, View over Bowral 1890

In 1890, Cayley painted in oils the view from his house on the outskirts of Bowral, overlooking the town to Mount Gibraltar. The painting was exhibited in the Grand Hotel alongside this photographic print of the work.

Old-time residents of nearby Bowral, where the Cayleys had relocated by 1889, remembered that Cayley himself bred gamecocks. They also recalled that he was well liked and wore a distinctive red coat. In March 1889, Cayley organised for examples of his work to be on show at the Bowral offices of The Bowral Free Press and Berrima District Intelligencer. He was talking of a return to Europe, the paper reported, and had won seven medals, including one from the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition. Four paintings flagged his arrival. The largest and ‘most striking’ was of a kookaburra with its young. The others were identified as a ‘firebacked’ bird (possibly a Diamond Firetail), a colonial redbreast (Scarlet Robin) and a blue wren (Superb Fairy-wren).

Three months later, in June, ‘the talented bird artist’ was seeking pupils, advertising private lessons in ‘Water Colour painting, painting on Satin, birds a speciality’. Nevertheless, it seems to have been a relatively prosperous time for the family. The same month, Cayley wrote to Edward Ramsay, Curator at the Australian Museum in Sydney, that he had no lack of commissions and was charging a handsome 12 guineas for a typical watercolour. He suggested that his main income was not from within Australia, rather from commissions in his home country, telling Ramsay that he was able to sell his pictures in England before they had even been painted. What was more, he informed Ramsay, he planned to soon return to the country of his birth: ‘I shall make a move in that direction in a few months’.

The museum had received a male and female specimen of the rare Blue Bird of Paradise, discovered just five years before. Its committee commissioned Cayley to illustrate the bird. Making an exception to its usual practice, the museum agreed to send the precious male specimen by rail to Bowral, where, Cayley reassured them, he had ‘a fine room and no end of birds’, adding, ‘I would see that every care was taken of the subject … I am sure I could do it justice’. He was equally concerned when a couple of months later he was freighting his painting back to the city. Having previously had a painting stolen from one of his cases, he told Ramsay, ‘I shall be anxious till I hear’.

Cayley had first drawn a bird of paradise in about 1886, for The Picturesque Atlas. Several expeditions to exotic and relatively unexplored New Guinea had ignited scientific and popular interest in the gorgeously plumaged birds and their bizarre courtship displays. In 1888 Cayley made paintings of several species of the extravagantly plumed birds. The public fascination continued and a version of the Blue Bird of Paradise painting was reproduced and appeared in the supplement to The Australian Town and Country Journal on 15 December 1894.

In June 1889, possibly in preparation for the birth of the family’s second child, Cayley advertised for a boy to milk their cow. The Cayleys were living in a hawthorn-fenced cottage, Buena Vista, on Oxley Street (now Oxley Drive), with glorious views to the west over the town of Bowral to Mount Gibraltar. It was there, in September, that a daughter, Alice Rochfort, was born, joining three-year-old Neville William. Alice was named for the sister closest to Cayley in age.

From Buena Vista, Cayley painted a large canvas of the view to Mount Gibraltar. The oil painting took in the heart of the town, showing the Grand and Royal hotels, the Free Press office, the church parsonage and a glimpse of Moss Vale in the distance. The Free Press reported that Cayley was undertaking the work because he was:

under the impression it would be a sin to allow such a beautiful landscape to remain without it being re-produced in the best way possible, so that the whole of the colonies may see what the sanatorium of New South Wales is like.

On 18 January 1890 the landscape was nearly finished and by the 22nd of the month it was on its way to Sydney for framing. By 8 February it was back in Bowral, hanging in the Grand Hotel alongside a photographic print of the work, and attracting much commendation. The photograph had been made so that the work could be reproduced, presumably by handcolouring the photographic print. The Free Press report described the original oil as large—5½ feet (1.7 metres) in length and 3½ feet (1.1 metres) in depth—and ‘charming’. Cayley himself is reported to have said simply: ‘I think the public will like the picture’.

Cayley’s view of the mountain was raffled, with tickets a guinea each. The lucky winner was J.L. Campbell of the Grand Hotel; the painting was to hang at the hotel for a time. A couple of years later, Campbell sold the hotel and the townspeople attempted to raise enough money to purchase the painting for donation to a Sydney gallery. They were unable to raise the required 50 pounds and the work may subsequently have been disposed of by an art union.

Neville Henry Cayley, Albino Kookaburra 1890

The white Laughing Kookaburra depicted by Cayley in this watercolour was collected in the Bowral district and was thought to be the first known instance of albinism in that species. The specimen ended up in the Australian Museum.

Neville Henry Cayley, Robin Red-breast in the Snow 1894

Cayley was frequently broke and often paid his bills with paintings. He is thought to have painted this scene of an English Robin in falling snow, complete with a sprig of mistletoe, as payment for some haberdashery purchased by his wife. The shopkeeper reportedly wanted a painting that would remind her of Christmas in Ireland.

Also on sale at the Royal Hotel that February of 1890 were 20 ‘splendidly mounted and framed’ Cayley watercolours. They were mainly of birds but included paintings of a koala and its young, and kangaroos. Among the bird paintings were four of kookaburras. One was a white kookaburra, which Cayley had collected locally and which, his son Neville junior suggested many years later, was possibly the first albino kookaburra on record. The works were advertised as ‘exclusively Australian Birds and Animals, for the faithful painting of which the Artist is held in the highest repute by connoisseurs and experts alike’. All except two sold, for between two and five pounds each, for a total of 61 pounds 11 shillings.

Cayley had indeed decided to leave town, but not for Europe. He gave his reason as the blasting at the nearby quarry. Nonetheless, he was frequently on the move, and the family had been in the district for two years. An April auction disposed of ‘the whole of the household furniture and effects’, bedding and glassware included, as well as 20 paintings, and the cow: ‘a good quiet cow just at calving’. Before he left, Cayley donated a guinea to the fire fund to assist the new owners of the Grand Hotel to replace the stock and tools of trade consumed by a blaze the previous month.

Before leaving the area, Cayley also demonstrated his sense of social justice, laced with his wry sense of humour, in a letter to the editor of the Free Press. He had been outraged by a cutting sent to him from his friends in Grafton that described how an Aboriginal man had repeatedly evaded an army of pursuers. The offending article ended: ‘for the sake of the Upper Clarence it is hoped that the escapee will soon be arrested’. Cayley wrote in defence of the escapee, Tommy Ryan, observing that it had:

taken fully 20 well-armed men (crack shots), including police, to miss the capture of one poor, unarmed blackfellow three times … even if the blackfellow had been guilty of murder … such pursuit would hardly have been requisite. As a conundrum it reads thus; if it takes 20 well-armed, & c., to catch one blackfellow, how many unarmed blackfellows would it take to catch one whiteman … Kindly find room in your valuable paper for some words to show that there are some people who respect color.

In 1890 the National Gallery (now the Art Gallery of New South Wales) purchased one of Cayley’s watercolours for its prestigious collection. Titled Dues, it was the Bowral Black Duck. The Sydney Morning Herald reported it was shown ‘poised in air’ at the moment it was shot. The article continued, ‘The small feathers struck from it break the outline. It is a good bit of work’.

It appears that the Cayleys had moved to Fischer Street in Petersham, Sydney, and that they remained there into 1891. Despite his increasing recognition, Cayley was ever in financial trouble. In May 1891, he again ‘relinquished housekeeping’, according to the advertisement in The Sydney Morning Herald, auctioning all his household effects in Leichhardt.

Why would Cayley again sell his family’s possessions? Quite possibly, he was among the casualties of the recession of the 1890s throughout the eastern Australian colonies. The economic boom that had begun with the gold rushes of the 1850s and had been bolstered by high prices for wool and wheat began to collapse, and many local banks failed. The demand for luxuries such as artwork dwindled and for the next few years Cayley’s paintings flooded the market as people sold up.

Cayley also had a reputation as a drinker. Supposedly, he would quickly whip up paintings to fund his habit, sometimes swapping his works for grog across the bar of the local hotel. A hint of Cayley’s enjoyment of revelry can be found in an 1888 article by ‘Telemachus’, the pen name of journalist Francis Tyler who worked for a time for The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser. Tyler was writing about a depiction of two dead robins that had been painted by Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward La Trobe Bateman when he visited Australia in the 1850s. The painting, Tyler, thought:

could only have been painted by one other man in Australia, the other being Neville Cayley whom I saw last … on the Clarence River in New South Wales—yet full of mirth and melody, and singing the whole night through ‘A Shepherd I from Arcadie’.

Neville Henry Cayley, Cobb & Co. Coach on the Road in Forest Setting

Cobb and Co mail and passenger coaches were the main means of public transport overland to the far-flung towns of New South Wales and elsewhere. Cayley’s preference for unspoiled places with lush forest and a diversity of birdlife saw him make good use of the horse-drawn vehicles.

Among the items auctioned from the Cayley household were artworks, ‘almost new’ furniture, and even the birds that must have served as models:

Works of Art, Engravings by well-known artists, handsome Bedsteads, Wire Mattresses, Duchesse Toilets, Tables, Couches, Austrian Furniture, Crockery, Mahogany Wardrobe, Curtains and Cornice Poles, Carpets, Linoleum, Bird-cages, Kitchen Utensils, lot of Sundries, fine lot of well-bred dark Brahma Fowls … Magpie, Whistling Crow, Butcher Bird, Canary, &c.

A little later in 1891 Cayley donated six stuffed birds to the Australian Museum—Yellow, Yellow-rumped and Striated Thornbills, two fantails and a whistler. The donation gives an insight into the way Cayley worked: via efficient use of a double-barrelled shotgun. It was the only way he could closely view most birds. In 1948, Grafton solicitor and local historian Robert Craigie Law recalled that at the age of 15 he met Cayley when he was living at Casino, and watched him at work:

His speed and precision were astounding … He had a large trunk filled with the skins of birds, complete with beaks and claws, but not stuffed or mounted. Always beside him on the desk was the skin of the birds he was painting … he paid particular attention to the eyes, beak and feet.

The fact that Cayley used dead birds as his reference is evident in his work: rather than drawing the shadow that would be cast by the sun in a natural setting, he painted his birds evenly illuminated.

In March 1892 Cayley was back in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales. He was living in Ballina, at the mouth of the Richmond River, some 100 kilometres north of the Clarence River by steamer or Cobb and Co mail coach. The graceful steamers would have been the more comfortable option. The coach track through the forests was edged with ringbarked trees, and the drivers had to stop now and then to move fallen limbs aside. Travel was a steady seven miles (11 kilometres) an hour and the horses were changed every 20 kilometres or so.

Around that time Cayley may have earned some income from a crayon portrait of Grafton police magistrate A.L. McDougall. The portrait was among the works contributed by the Art Society of New South Wales to the annual flower show and fine art exhibition held in October 1892 by the Clarence Pastoral and Agricultural Society.

In August 1892 Cayley was in Casino—60 kilometres to Ballina’s west, accessible by steamer, and still within the Northern Rivers region—preparing paintings for the International Exposition in Chicago. He and his wife, Louie, as she was affectionately known, were staying at the home of Louie’s sister, Ada, whose husband was the influential Frederick George Crouch— general store proprietor, steamer owner, timber trader and mayor of Casino Municipality from 1883 to 1885 and again from 1890 to 1891.

Crouch’s Trade Palace was the largest store in Casino. Built to make the most of the natural light, it boasted a fine window display, with groceries and ironmongery to one side of the store, and drapery and clothing to the other. The boot and shoe department was at the back, adjoining a wine and spirit store behind which was the glassware and china department. Hardware, oil and paints, a large storeroom of sugar, a haberdashery department, and offices completed the store. Across the road another of Crouch’s stores sold furniture and bedding, galvanised iron, fencing material and other goods. The town boasted several other stores, an excellent school of arts, the Oddfellows’ Hall, newspaper offices, several banks and churches of various denominations, two hotels and a school, a substantial courthouse and gaol, a sawmill, a wharf and a fine bridge spanning the river. Despite the trappings of modern late ninteenth-century life, there were still a few major ‘troubles with the blacks’, as it was often couched, ousted from their prime lands. The late 1880s saw the last of the murders and mass cattle-spearings attributed to the Aboriginal people of Richmond River, and of the lawless retributions from European squatters.

A reporter for Lismore’s regional newspaper, The Northern Star, stated optimistically that Cayley’s pictures were ‘now recognised as works of art the world over’ and that it was ‘a certainty that he will deservedly earn increased fame’. Hung in the New South Wales court at the 1893 Chicago exposition, the largest and last great exhibition of the nineteenth century, Cayley’s watercolours received an award. Advertisers quickly picked up on his success. In Sydney, Dymocks bookstore was selling finely lithographed Christmas cards promoted as ‘reproductions in colours of Mr. Neville Cayley’s famous pictures of Australian birds, which are now being exhibited at Chicago, where they received an award of merit’.

Neville Henry Cayley, Not titled (Australian Gamebirds) 1888

After his initial success with a painting of a Black Duck depicted at the moment it is shot, the spoils of hunting remained a favourite subject of Cayley. This beautifully arranged and painted tableau features various game birds, including ducks, quail and waders, as well as a Masked Lapwing, a Ground Parrot, a Rainbow Lorikeet, a Brush Bronzewing, a Superb Lyrebird, a Noisy Pitta and a Night Heron. Two Grey Teal hang curing from a hook, while the other birds are tumbled over the floor of the pantry or cool-house.

In March 1893 an auction of 25 framed works by Cayley was held at Casino. It was claimed to be the last chance to purchase from a good selection of his paintings because he was planning to take his family to England at the end of the year. It seems, however, that despite several attempts, Cayley never travelled overseas. The Cayleys were back in Sydney, now living in Glebe at the home of Louie’s parents William and Adelaide. There, not long after her father’s death in April 1893, Louie gave birth to their last child, Dorothy Loris (also known as Doris).

In December 1894 The Northern Star reported that its proprietor, Thomas George Hewitt—who had long been a supporter of Cayley, having bought the first of his paintings when he lived in the district 13 or 14 years before—had received the news that Cayley had moved to Woonona. The Woonona Bulli district, on the south coast of New South Wales, just north of Wollongong, was a growing commercial hub situated in the Illawarra, another of the scenic, bird-rich, forested areas that so attracted Cayley. There was also wealth in the district—from cedar logging, agriculture and ‘black diamonds’ (coal).

Old Bulli residents remembered that in the late 1880s, after the rail link was opened on Queen Victoria’s jubilee day in 1887, Cayley visited from Sydney quite frequently to sketch the birds in the rainforest. He stayed at the Railway Guest House where he showed an interest in the canaries routinely carried into the local coalmines. The canaries were one of the few safety devices available to miners. The birds are more sensitive than humans to toxic gases such as carbon monoxide, methane and carbon dioxide. Hence, if they showed signs of distress or died, it was time for the miners to evacuate.

Meanwhile, Aldenhoven was working hard to promote Cayley’s paintings. He often displayed the latest example of Cayley’s work in the window of his Hunter Street store and in 1894 he was trying his chances in Melbourne, having sent 130 watercolours to the Federal Coffee Palace in Collins Street for exhibition and sale.

Among the works hung in Melbourne by Aldenhoven were Hard Hit, Dignity and Impudence and many other early titles, presumably copies by Cayley himself. Also on show was a painting that showed the exceptional artistic skills that Cayley too rarely demonstrated: A Day’s Shooting, illustrating 28 different game birds, rightly advertised as his masterpiece (now in the National Gallery of Australia). He had painted the original in 1888 for the Melbourne Centennial International Exhibition.

Cayley was promoted to the Victorians as the best bird painter since John Gould. It was pointed out that he also had a link to the colony, having lived there when he first immigrated to Australia:

The artist, who we are informed commenced his studies in Gippsland, possesses an innate knowledge of the portraiture of birds, whether in motion or repose, alive or dead, delineating their plumage with singular fidelity and conscientious care, while proving himself at the same time a skilful colourist. Some of the drawings are life-sized, and close observation has evidently familiarised Mr. Cayley with the characteristic habits and attitudes of his subjects, their modes of flight, and their particular habitat, so that each picture is to some extent a page of natural history. The whole of the drawings are to be faithfully reproduced on stone, and then coloured by hand, under the immediate supervision and with the final touches of the artist himself. The undertaking is a very bold and costly one on the part of the publishers, and it is certainly deserving of support by the lovers of art, by sportsmen, and by students of ornithology.

Tom Flower, Two Magpies Fighting over a Bone

The mysterious ‘Tom Flower(s)’ was a copyist and forger of Cayley’s work. In the painting above, Flower refers to Cayley’s Bone of Contention (first painted in about 1885), which shows two magpies squabbling over a bone.

Neville Henry Cayley, Magpie 1901

Flower’s work is remarkably similar in style to several paintings which are signed ‘Neville Cayley’, but which are not typical of Cayley’s usual style (see for example Cayley's Magpie, above).

Neville Henry Cayley, Magpie c. 1897

A more typical Cayley magpie is the 1897 work, above. Historical records suggest the existence of an artist named Flower around this time, although it has been suggested by some that the name was a pseudonym used by Cayley himself. Flower’s relationship with Cayley remains to be established.

The book hinted at, entitled Australian Birds (c. 1895), did indeed prove too costly and problematic for Aldenhoven. The artworks intended for the publication were photographed and printed at a size of around 27 by 35 centimetres, then handcoloured and signed, the latter an arduous task completed by Cayley himself. They were also assembled and bound individually. The only information provided for the reader was the name of the bird pictured. Unsurprisingly, few copies were produced.

In the same year, Aldenhoven and Cayley published several ‘Important notices’ claiming exclusivity to the copyright of all Cayley’s bird paintings, warning that ‘Any person selling or causing such pictures to be sold, will be prosecuted as the law directs’. Possibly it was a response to the fact that a number of his paintings had been released from liquidation auctions, or from copyists of his work, flooding the market. Whatever prompted the advertisements, Cayley needed the income, and was selling work privately. Aldenhoven would also have needed to secure his stake in Cayley. In December, Aldenhoven was in the process of building a large, well-lit gallery at Hunter Street, where Cayley’s work would have pride of place. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that:

Anthony Alder, Kookaburra on Branch c. 1890

Queensland Museum curator and contemporary of Cayley, Anthony Alder, had some success with his oil paintings of birds, but was ultimately eclipsed by Cayley. The two artists’ compositions were not dissimilar.

the latest productions of his brush clearly indicate the work of a well-controlled genius. No less than 120 original pictures by Cayley have been secured by Mr. Aldenhoven, but probably one of the finest in his extensive gallery is the ‘Convention of Parrots.’ In this the artist has displayed to the fullest extent his regard for detail, his brilliant colouring, and unsurpassed faithfulness.

It was around this time that Cayley’s colleague from the Clarence, Edwin Cox, began giving free art tuition at the Grafton Fine Art Society. In 1888 Cox exhibited in the Clarence Pastoral and Agricultural Society’s annual show a watercolour entitled Wounded Duck and, by the time of their 1903 exhibition, he was reportedly painting the best birds he had ever done: ‘upon a level with the late Cayley, if not beyond him’.

The next year a visitor to Grafton submitted an article under the pen name ‘Orara’ to the local Clarence and Richmond Examiner. Orara had visited Cox to view the watercolours of 150 species of northern New South Wales’ coastal birds that Cox had painted in his spare time. Orara opined that demand for the paintings would increase if only Cox were more widely known. It seems that Cox had learned well from Cayley. He too referred to bird skins. As Orara, who knew Cayley, observed: ‘Every bird is painted from nature: it is first prepared by Mrs. Cox, and then this born artist gets to work at it, working on the same lines as Cayley worked’.

Did Cayley’s success eventually tempt Cox to go a step further and add Cayley’s signature to his Cayley-inspired watercolours? Someone certainly took that path. A number of Cayley paintings have long been suspected to be fakes; Keith Hindwood, Neville William Cayley’s colleague, was one person who believed there had been counterfeits. Given the flood of Cayley paintings, and the copious copies of old favourites made— sometimes carelessly—by Cayley himself, it would not have been hard to pull off a forgery.

And who was the mysterious Tom Flower(s) whose paintings of birds so flagrantly plagiarised Cayley’s style and subject matter? Some say it was Cayley himself, but there is no obvious reason why Cayley would have wanted to produce work under a pseudonym. Flower’s watercolours of birds included depictions of shot snipe and ducks, snake-killing kookaburras and squabbling magpies. He even painted a fairy-wren confronting a kookaburra. Paintings signed ‘Tom Flower’ are very similar to Cayley’s in every way but tend to be more finely finished. There are also paintings signed ‘Neville Cayley’ that have an atypical oval backwards-drawn loop to the tail of the final ‘y’ that may well have been by Flower (see for example Magpie on page 35, bottom left).

Flower was a direct contemporary of Cayley, born only a couple of years before him. His paintings were advertised intermittently at auctions of household effects, often alongside Cayley’s, between 1892 and 1929, but were never shown in an exhibition. It is possible that he was Thomas Frederick Flower of Dunrobbin, Brighton Boulevarde, Bondi, who is listed in the 1930 and 1933 censuses as an artist. Flower married Adelaide Mary Mather in Grafton in 1880, so he could have met Cayley shortly after. He died at Paddington in 1936 aged 84, and, unusually, no parents were recorded on his death certificate. Perhaps he and Cayley knew each other, or even had an arrangement of some kind.

In 1895 the peripatetic Cayley family had a new address: at Glassop Street, Balmain. Cayley had work accepted for the inaugural exhibition of the Society of Artists, opened by Sir Henry Parkes. The new society had been formed by a breakaway group of artists that included Julian Ashton, Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton, Sidney Long and most of the notable male and female painters of Sydney. Their frustration was that the exhibitions of the Art Society of New South Wales were not selective enough, inclusions being decided by the membership, mostly made up of laymen and amateur artists. For a time the two societies held rival exhibitions, even staging them at about the same time. In September 1895, when tensions were at their greatest, The Sydney Morning Herald may have been being mischievous when it reported that the Society of Artists accepted 250 and rejected 100 paintings, whereas the Art Society rejected 162 out of 520 submitted for their exhibition (in other words, both rejected about a third).

The attempt to lift standards and create a professional art industry was somewhat successful; Australians were slowly becoming more cultured, but art was still a hard way to make a living. Many artists headed overseas, and in 1902 the Society of Artists was absorbed back into the Art Society, which the next year was granted its Royal epithet.

Cayley’s work was again chosen for exhibition with the Society of Artists in 1896. Some time that year the family apparently left Sydney again, and may have returned to the Wollongong area. Cayley entered three paintings, ‘which called forth much favorable comment’, in the Wollongong Agricultural, Horticultural, and Industrial Association’s annual show. Also in 1896, the enterprising Aldenhoven, having travelled south to Melbourne, took Cayley’s work north for a multi-artist exhibition and sale in Brisbane.

Brisbane taxidermist and artist Anthony Alder may well have taken the opportunity to view Cayley’s paintings. Both men had a special interest in birds and both were conservation minded. Alder too had exhibited in the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886, but, aside from some local success, he had not achieved the same renown as Cayley. Yet a year before the Cayley brothers arrived in Australia, Alder had been praised in The Sydney Morning Herald as ‘a most successful painter of animal life’, having exhibited in Brisbane three oil paintings of groups of Queensland birds. The previous month, July 1876, The Queenslander had reported on one of his paintings. Titled Rural Echoes it depicted:

two admirably painted life-size ‘laughing jackasses,’ perched on the limb of a gum tree, and making the echoes with that peculiar note which at first so startles and then amuses new arrivals in Australia. The plumage of these birds is not of a character to tax the skill of the painter in the treatment of brilliant color, but on the other hand, to make an effective picture from birds of their ungraceful shape and ‘quaker’ feathering was no trifling matter to accomplish, and Mr. Alder has made a most effective picture.

They were not Alder’s last kookaburras, which proved quite popular over the years. In 1895, the Queensland National Art Gallery purchased his painting of a pair of the birds for their collection. Both Cayley and Alder were pandering to public tastes, but apart from the difference in preferred medium—Cayley worked in watercolours, while Alder used oils—the similarity in their styles suggests that Alder might have had an early influence on Cayley, whose first kookaburras to go public were dated 1880. Brisbane was a relatively short steamer ride (200 kilometres) from Yamba. It may be that Alder visited the Clarence to obtain specimens for the Queensland Museum from the local naturalists.

Many kookaburra paintings later (Cayley is estimated to have produced over 1,500), in 1898, the Cayley family was settled at Wiley Street, Waverley, in the eastern suburbs of Sydney. That year Neville junior turned 12 and his youngest sister five. Possibly Louie and Neville were thinking of the children—at 12 their son Neville would have been close to starting high school and Doris, turning five, may have started primary school. They probably attended the nearby Eurotah School, also on Wiley Street. Certainly, Alice was a student at the school in 1900. Neville junior finished his schooling at Waverley State School.

Cayley was again working at the Australian Museum with ornithologist Alfred J. North. He was busy colouring photographic plates of eggs and drawing black-and-white sketches of birds for North’s book, the first volume of which had been released in 1889 as Descriptive Catalogue of the Nests and Eggs of Birds Found Breeding in Australia and Tasmania.

As the new century began Aldenhoven was advertising his newly opened gallery, enlarged and beautifully appointed, with a ‘very extensive collection of oils and watercolours [by] N. Cayley (the bird specialist) … and many other artists of note’. He was also still issuing a selection of birds by Cayley as Christmas cards ‘for friends abroad’.

Cayley was churning out paintings, often copies of his more popular works; in July 1901, 30 of his watercolours went on show and were snapped up by a single buyer. That same year saw the federation of the six Australian colonies into a nation, and a tour of the country by the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall. The Art Society of New South Wales presented the royal visitors with an album of 24 of their members’ work, each a little watercolour, including one of a pair of lyrebirds by Cayley. In August the society held its 22nd exhibition. Cayley, who had first exhibited at their second show 20 years previously, was among the artists whose work was selected. His magnificent watercolour Still Life, Australian Birds showed a whole shelf covered with dead birds. According to the critic for The Sydney Morning Herald, ‘the profusion of plumage so accurately tinted after nature by Mr. Neville Cayley makes the work important’.

In 1902 the trustees of the Australian Museum released the first part of North’s Nests and Eggs of Birds Found Breeding in Australia and Tasmania (dated 1901), for which the Descriptive Catalogue had been the precursor. It was, a reviewer for The Sydney Morning Herald claimed, ‘a credit to all concerned’. The publication contained about 25 photographic plates of eggs (see page 21), in some issues handcoloured by Cayley, who, The Australian Town and Country Journal reported:

has most delicately colored the plates showing the various eggs, the innumerable tints of which possess a charm of their own, and we are assured by Mr. North, who has devoted his life to the study of the subject, that all these paintings, when compared with the originals, will be found exceedingly faithful.

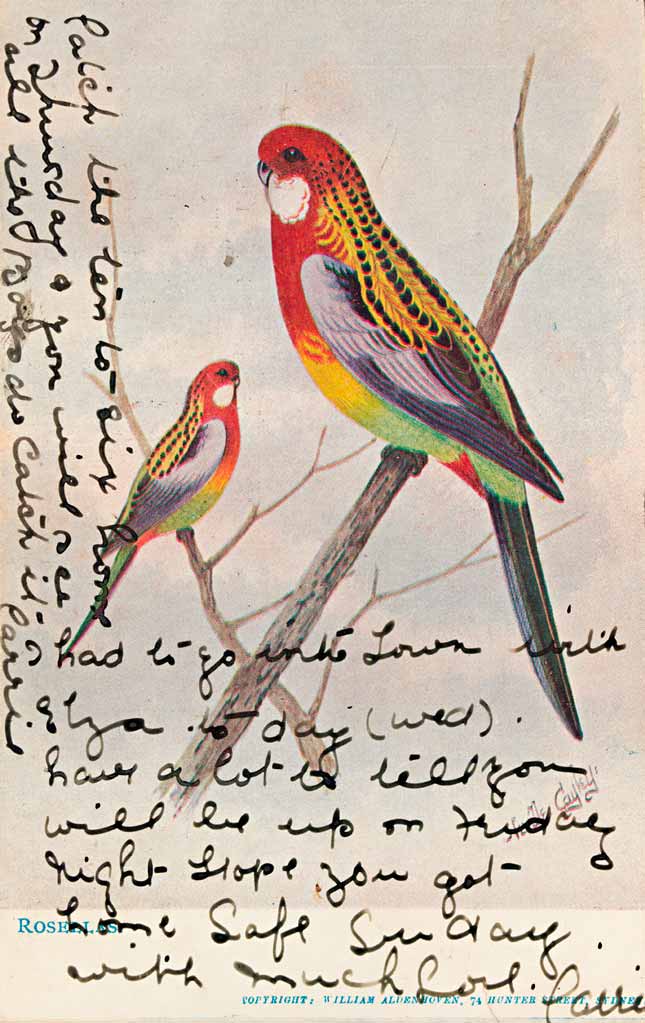

Neville Henry Cayley, Rosellas c. 1903

After Cayley’s untimely death, Aldenhoven produced several booklets and cards featuring Cayley’s images of iconic birds. The royalties must have been welcome to Cayley’s often impecunious family.

Neville Henry Cayley, Budgerigars 1895

Cayley painted this watercolour of a pair of Budgerigars perched in their favourite habitat, an abundance of seeding grasses.

The next year, 1903, Cayley’s chronic kidney problems finally caught up with him. After two years of suffering, at 6 am on Thursday 7 May, he died in Sydney Hospital. The cause was chronic nephritis (Bright’s disease), a painful condition possibly exacerbated by his renowned heavy drinking. He was not yet 50.

Cayley was buried at the local Waverley Cemetery. The death certificate stated that he was born ‘at sea off Dover’ to ‘Nathaniel Cayley’, occupation ‘Navy Captain’. These details appear to have been part of a family myth, maintained to the last. As for Cayley’s third given name, which has been much confused, his death certificate records it as Peniston, his baptismal record as Pennington and his birth record as Penniston, the latter his maternal grandfather’s middle name.

The death notice in The Sydney Morning Herald was widely repeated and borrowed from:

The artistic world sustains a loss in the death of Neville Cayley, famous amongst ornithologists throughout Europe and America, for his beautiful and faithful paintings of bird life in Australia … many art collections of importance in this country include one or more of his paintings … During her recent visit to Sydney, Mme. Melba personally inspected Mr. Cayley’s paintings, and purchased several of them.

Cayley had long wanted to publish a book on the Australian birds he so loved. The October after his death, John Sands, by arrangement with copyright holder Aldenhoven, launched a booklet, Australian Birds: A Beautiful Coloured Series by Neville Cayley. The book was advertised as being:

printed on art paper in colours, on one side of the paper only … the whole enclosed in gold embossed cover—a work of art. Each illustration a gem and worth framing.

The reproductions, of 11 of Cayley’s bird paintings including the old favourites Dignity and Impudence and Hard Hit, were a poor substitute for Cayley’s dream of a book that would popularise birds. Techniques for mass publication were limited, and the effort was a pale imitation of what might have been. Some of Cayley’s ornithological colleagues were outraged and sprang to his defence, roundly criticising the quality of the booklet, which was strangely mauve tinted, and judging it unworthy of the artist. A report in The Brisbane Courier, repeated in Cayley’s old haunts by The Northern Star, was scathing:

It is said that poets and artists and the like have only justice done to them after they are dead. In Neville Cayley’s case it is injustice that comes post-mortem. We are shown a kingfisher, which is no doubt much as Cayley painted it, but it is called a ‘Blue Kingfisher’. It does not follow out the old idea that the kingfisher in flying out from Noah’s Ark took the colour of its upper feathers from the blue of the sky, and the lower from the sun. In short, it is what is generally known as the purple kingfisher [now Azure Kingfisher]. Then there is a magpie, not a black and white, or even the dull brown and white, as one finds female and immature birds, but a purplish brown and white, the like of which is an ornithological curiosity. Again, we come to the Regent birds [Regent Bowerbirds], both males. Every Queenslander knows that the male Regent bird is of a bright but rich orange colour, and a velvety black. The specimens given and attributed to the dead artist, Neville Cayley, are of a pale primrose yellow and brown. It is questionable whether some law should not be introduced to prevent incompetent copyists from publishing pictures as those of recognised artists.

When the news of Cayley’s untimely death reached southern Victoria, the West Gippsland Gazette added information about his early life in Australia, noting that the artist had:

for many years lived in Drouin where he was well known by Mr. C. H. Round and many other old identities of this district.