[ 4 ] Evacuation

What a choice! Sending your babies away or keeping them here, at home with you, in danger.

Some London children had a very different, if sometimes only temporary, experience of living through the war years: they were evacuated away from our street and their East End homes.

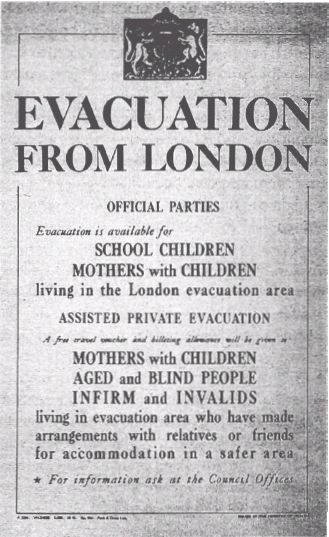

If they chose to, the sufficiently well off, or those with family living away from any potentially unsafe areas, could make their own, private arrangements for their children, and maybe even themselves, to live elsewhere for the duration. For the rest of the population, it was the government-organized evacuation or nothing.

Bureaucrats divided the country into zones, with each sector falling into one of three designated types. There were the danger areas, which would be evacuated; the supposedly safe reception areas, which would take in the evacuees; and the remaining areas, which were deemed to be neutral. The populace was similarly sorted and labelled: children, pregnant women and those considered to be a priority, such as the visually handicapped, were to be shipped out of the danger zones. This was not only for their safety; it was important to clear the risky areas for strategic reasons. Buildings, from hospitals to schools, and staff, from medical personnel to communications workers, would be required for war work, not for looking after what might prove to be helpless, inconvenient or even troublesome civilians.

The complex plans required for mass evacuation were in place well before the outbreak of war, including the compiling of registers of everyone concerned, but things did not always go to plan. Originally, it had been thought by the government that up to 3.5 million individuals would be officially evacuated to places of safety, but this number was never reached, due to a combination of factors. Families showed a widespread reluctance to be separated, surprising the middle- and upper-class authorities, who were more accustomed to being separated from their children. There was also an increasing belief that things wouldn’t be ‘too bad after all’ that set in during the Phoney War. And then there was homesickness, which on occasion was unfortunately exacerbated by the less than warm welcome given to those turning up in various reception areas around the country. Eventually, only 1.5 million took advantage of the evacuation scheme, but even in its abbreviated incarnation, this was an impressive accomplishment, especially as it was carried out in those comparatively car-free days, using mainly public transport.

On 1 September 1939, the gears were cranked and the massive plan was put into action. For the next few days, much of the country’s train and bus network was given over to this unprecedented movement of people. Nine one-way routes were especially plotted by the police to allow vehicles to make their way out of London, while Walter Elliot, the Minister of Health, issued assurances that it was all only a precaution, and a shining example of what a free people could achieve when they put their backs and hearts into a job. With this vast scheme in place, the beginning of the blackout and the mobilizing of the ARP, it would have been hard to deny that war was really about to happen.

Some of the evacuees were to have very good experiences, being shown nothing but kindness and generosity by their hosts, and making lifelong friends with people who were, in some cases, to grow as close to them as family. Yet despite the minister’s enthusiasm, evacuation was definitely not universally appreciated by those involved. Stories of hardship and neglect abound, showing that it wasn’t only the enemy who could be cruel and brutal. The ways in which some young East Enders were treated resemble episodes from one of Dickens’s more harrowing novels more closely than the comforting visions painted by the local press of ‘our kiddies’ frolicking in flower-strewn meadows.

There were memories of being singled out for being Jewish; of a more general prejudice against ‘dirty Cockneys’; and of experiencing such misery at their mistreatment that children ran away – one man even recalling the hospital care he and his sister required when they finally made their way back to their home in east London. As in other sections of this book, some people decided that they couldn’t bear to have their stories told. Regrettably in this case, it was out of a misplaced sense of shame – which is perhaps hard for those of us who haven’t experienced such cruelty to understand, as it seems so obvious that the adults responsible should be the ones who are ashamed.

There were plenty who, even before they left, had a good idea that leaving Mum and Dad behind and going off to live with strangers might not turn out to be the jolly adventure they had been promised.

The children who didn’t want to be evacuated were tugging and crying, while their parents tried to hide their tears and their feelings, but were shattered by what was happening to them. There had always been togetherness, with families sticking together through thick and thin.

We were so little, with our gas masks and our little cardboard labels. Like little parcels waiting to be sent off, but to who knew where? It was so hard to understand what was going on. It wasn’t as if one of our aunties or our nan was taking us somewhere. We were used to that. No, this was different. We were going off to be with these ‘nice people’ somewhere. But who were they?

Young Alan – speaking below – had a good idea, and he wasn’t going to have any of it.

I remember a lady calling by to ask about me being evacuated. We had a tiny place – a dump really, no bathroom, no hot water – and my dad bawled up the stairs, ‘Alan, do you want to be evacuated?’ I called back down to him, ‘No thanks, Dad.’ I can hear to this day that woman’s incredulous voice. ‘Surely you’re not going to let the little lad decide for himself?’ ‘Well,’ said Dad, ‘he’s got to start someday, he might as well start now.’ I was fully aware that I could be killed, but decided I’d rather go with my parents if we copped it.

If parents did agree to send their children – or to go with them, in the case of mothers with very young children and babies – the Londoners from our street didn’t always settle in their new surroundings. And it wasn’t only because of the welcome that some of them received. It was as much of a culture shock for those in the reception areas as it was for the East Enders, arriving as they did after the discomfort of their long journeys on trains and buses without lavatory or washing facilities, and with their city clothes and ways so unsuited to rural life.

We travelled by train and then coach, looking out on the pitch-dark countryside. The driver lost his way as all the signposts had been removed for security. When my mother found out that she was to be separated from my brother and me she said, ‘I would rather sleep in a field than be taken away from my children’ … Later we were found places with a family. From what she told me, I don’t think all the local residents were too pleased to have us Londoners there … It must have caused disruption to their lives. Eventually we went to live in a rented stone-floored cottage … My mother found it quite lonely. [And when] there was a lull in the bombing we went home to London.

They weren’t the only ones who fled, although some took a little longer to do so.

Mum took us somewhere out in the country. We got there on the Saturday and she went with us upstairs to unpack, then, when she went down, we packed all our stuff again. We didn’t want to stay there. And so it went on – packing and unpacking. She stayed with us overnight and in the morning she couldn’t bear to leave us. We went to the coach with her, and, even though she had no fare money for our tickets back to London, the coach driver was kind and let her bring us back.

When we were evacuated, Mum was pregnant with my brother, as were a lot of the other women, including one of my aunts. It must have looked like a human convoy of pregnant women and kids, all of us labelled and carrying bags and boxes and gas masks in cardboard-box cases. I was squashed into the corner on a big train, with my mum, aunt and all my cousins. We spent the night in a big hall, where we were given blankets, pillows, and packed food and tea were dispensed to us. Then on another train to where we were going to stay on the borders of Yorkshire and Lancashire. When Mum went into hospital up there to have my brother I was taken to see her. I can remember that hospital smell. She cried when she saw me. They’d cut off my hair because I’d caught fleas. And Dad had been given leave from the army to visit Mum and the baby, and I didn’t know him. In the time between his last leave and him coming to see Mum and the baby, I’d forgotten him. Mum was so unhappy that she discharged herself from hospital and took us back to London to live with Nan and Grandad.

My nephew and I found ourselves most unhappily staying in a house with a woman whose husband was away in the army. She had only one son, slightly older than my nephew and me, and we hated him because he was a spoilt, over-indulged, fat brat who made our lives very uncomfortable. [We were not looked after and] soon learned what being hungry meant. We were half-starved, and it can be imagined how we felt when we were given half an egg weekly and the son had one or two each day, which he enjoyed eating in front of us at breakfast. This was in the countryside, where such items were not so scarce. We were sent out early mornings before school to search the fields for mushrooms in the surrounding fields – not particularly enjoyable, because the low morning mists [made] it hard to avoid the cow pats whilst fumbling for fungi. This led to a cold-water clean-up before [we were allowed] to enter the house on our return. One day, during a rare visit from my sister Ada, her son told her how really unhappy we were and we were back to London in no time.

Various reasons were given by some of the Londoners who resisted returning home despite their unhappiness. These included having no home or family left to go back to, having gone through too much in the bombing to be able to face it again, and finding the strength to stay in the country because they believed it was the right thing to do for their children.

This family, for instance, was definitely not impressed with the countryside and its inhabitants, but the mother refused to return to London, deciding that it was best to stick it out for the kids.

Dad was in the army at that time … stationed about eight miles away. He used to walk the eight miles [to the big house where some of the children were evacuated with their mother], but Lady E– [the owner] was not too keen to allow Mum and Dad to be alone together in the house. Dad would have to climb through the windows without Lady E– seeing him. That is when my younger sister, S-, may well have been conceived … We eventually moved to a small empty cottage in the village. Mum had to squat there in order to have somewhere to live and to bring my three sisters from [where they had been evacuated to] and where they were not happy. Mum was a strong-willed woman and broke the law several times to protect her family. We were treated by some of the villagers as outcasts and were insulted frequently. We were told to go back to the slums of London and called cowards for leaving there. One day a bomb landed several miles from the village and most of them were at panic stations. We had the last laugh that day. The lady in the next cottage to us was always rowing with Mum and went too far one day. Mum either whacked her or threw a bucket of water over her to calm her down and had to go to court for it. When the magistrate heard the circumstances and the strife Mum was going through, he dismissed the charges. That did upset the neighbour, but she left us alone after that.

The villagers might have thought that the East End was a slum, but housing conditions in some of the reception areas weren’t exactly plush.

The cottage was very small and contained the barest items of furniture … We had no running water inside and only an outside toilet. The only heating came from a large kitchen range [on which] all the cooking had to be done … In the winter, being the eldest son, but being only five or six years old, I had to go to the outside coal shed and defrost the only tap with lighted newspapers round the pipe until the water ran freely. I say a coal shed, because in one corner, next to the tap, was a heap of coal dust which I used to go through to try and get some small lumps to burn on the range. It never seemed to work because the coal was no more than dust and seemed to put the flames out. My sisters and I were always in the woods nearby, collecting logs.

[The] toilet was outside in a large shed away from the house. This consisted of a cubicle inside the shed that had a lift-up wooden seat with a hole in the centre in the shape of a toilet seat. Under that was a large round bucket for catching you-know-what. About once a fortnight I had the task of emptying the bucket … I would dig a large hole in the garden behind the shed under an apple tree and empty the contents of the bucket into the hole. I would cover it over with soil but because the contents were very smelly and very wet it took some time to disperse … The toilet paper consisted of any newspapers we could get hold of. This was torn into small pieces and tied together in bundles to hang on the wall of the shed. It was always a luxury whenever we could get hold of some old telephone directories or similar paper that was softer and didn’t scratch the tender parts so much.

We’d tried going away, out to Norwich. But it was filthy. They kept their coal in the bath and they all had fleas. Mum tipped the coal out and we all had a good bath. Then all the kids from the family wanted a bath too. They were disgustingly dirty. At night, Mum would spread out a sheet of paper and comb her and all our hair out with a fine toothcomb, to check we hadn’t caught anything off them. She couldn’t stand it. She brought us all home. ‘If we die, we’ll all die together!’ Back in London, the houses got damaged by bombs, but the mums did their best, they kept them nice, and, despite everything, dustbins were always emptied. My mum always had a paintbrush in her hand. She did her best to keep it nice, respectable.

After being appalled by examples of the lack of generosity and blatant unkindness shown by some in the reception areas, and the not always admirable behaviour of the evacuees, it was a relief to hear the much happier stories. Many people recalled with great warmth how they had kept in touch with their country ‘families’ for years after the war had finished.

I was one of the hundreds of mothers with babies evacuated from London. I took with me my little niece, who was too young to go with the school children. Together with a small bag of belongings, and with our gas masks over our shoulders, we tearfully assembled at the railway station at 7 a.m. The journey began some time later – delayed by a false alarm. The first stop was Colchester. Red Cross nurses were there on duty, waiting to top up our babies’ bottles with water. The journey continued, with several more stops, until we reached Stowmarket in Suffolk. Scores of tired mothers and screaming babies were assembled in the great square in front of the station to await further transport. Again, volunteers were on hand to give us water and encouragement. I was eventually told to board a bus and finally arrived at a tiny village on the borders of Essex and Suffolk, close to Manningtree. Darkness fell as we entered the school to await our hosts, and a motley crowd they were – but no more than the crowd that had landed among them. It was now six o’clock in the evening and I was longing for someone to offer me hospitality, when one dear old lady came forward and invited me to stay. I answered rudely, ‘I don’t care where I go, so long as I can change my baby’s napkin.’ These words were repeated many times in jokes afterwards, and were the beginning of a wonderful friendship that would last to the end of her days.

When evacuees were sent to certain parts of the country, however, questions about their happiness weren’t even raised. Admittedly, the smug privilege of hindsight again comes into play, and it is easy for us to see that some of the places chosen as safe havens for bombed-out East Enders were anything but, and actually put them right back in the line of fire.

We went from a school in Old Ford, where I lived. I was seven years old, my sister was only four and my brother was ten. [We went] to a village in Oxfordshire, where the women came out and took their pick of us. My brother took everything in his stride, my sister was too young to know about anything, but I was stressed out. I wanted my mum. I stayed with my sister and my brother stayed with someone else. We did not stay there long because it was near an airfield, but while we were there I had bad dreams and walked in my sleep.

However, the following young boy would probably have preferred to stay in the danger zone on the coast, where he was sent initially, than live on the farm where he and his brother eventually fetched up.

I went with my mother to St Leonards at Hastings. I mean, it’s the most silly place they could send us. Everyone’s talking about an invasion! When it did get naughty down there, I went with my brother to Wales. It was an experience that I can look back on with pride, because of the way the boys were picked out. My brother is much older than me and the farmers literally – and this is the Gospel truth – they went down the line feeling the muscles of the boys.

One of the farmers picked the boy’s brother – who was twelve and well built – but because he was only seven and puny, they didn’t want him. His brother, however, insisted they stay together, and they were both taken to the farm. It wasn’t to prove a pleasant experience for either of them.

... we never saw a sweet, never had our sweet coupons, [and] they used to open every letter we sent home and open every letter my mum and dad sent to us. My brother sneaked a note in the post and that’s how we got out. The thing I couldn’t understand was what was so special about their toilet … The farm had a toilet outside, I’m not sure if it was a flush or chemical one to be honest, because – I couldn’t understand why – we weren’t allowed to use that toilet at all. We used to have to go in the field, summer or winter. I can remember looking at that toilet and trying to puzzle it out. We’d come from an LCC* flat and we had flush toilets, bathrooms and everything. I just couldn’t understand that, why we weren’t allowed the toilet. Just like I could never understand the London schoolteachers allowing those elder boys being lined up and the farmers feeling their muscles. I could never understand how they allowed that, because they were there, watching. We had to walk three miles to school and three miles back to [the farm, where] the farmer ruled the household like a rod of iron. His word was law. He had a son, and the only time I can remember me and my brother being treated was when we caught the son in a pub. His father was a strict Welsh Methodist and so the son bribed us by buying us a lemonade.

My brother worked really hard on that farm, but we weren’t allowed to sleep in a bedroom. We slept on the landing. But they literally – and you can verify this with my brother – kept us so hungry, this is truly hungry, that in one of the bedrooms off the landing [we found] they used to store all their fruit. My brother, it’s not a nice thing to say but it’s the truth, he found that if he could put a knife behind the catch and pressed it, the lock would trip, and we used to eat fruit right, left and centre. We’d have to eat the apple core, the pips and everything. But it did rebound on us. We made ourselves ill with all the fruit and had to be put in hospital over Christmas. That was the best time we had in Wales.

There are other stories that, when we hear them as adults, make us wonder how anyone could treat children in such a way – no matter how differently they behaved from their host families, or what ‘dirty Cockneys’ they supposedly were. Even the following little tale of a child’s real pleasure at being treated decently, and then feeling driven to eat foodstuffs intended for livestock, can make us gulp back the tears, as can the little girl’s story after that, in which we hear about her panic and how she tried to protect the other children in her charge.

One of the local farmers took me to an American Air Force base nearby to collect the kitchen waste for his pigs. Whilst I was near the kitchens an American cook came out and asked if I wanted a sandwich. You can guess how I felt about some extra food and said, ‘Yes.’ He came back from the kitchen with two thick slices of bread containing a large cooked chicken leg. That was most enjoyable, and I shall never forget the taste of that huge meal. Another time I remember helping the farmer who was boiling up some potatoes in a large iron pot, bigger than a dustbin, in his yard. These were for his pigs and smelled quite nice. When cooked, the peel came off quite easily, so I took one and ate it. It tasted nice and I thought those pigs were eating better than me. I also went to nearby fields and dug up swedes and mangel wurzels that were meant for cattle feed.

We were evacuated with the first lot just before war was declared. We didn’t want to go – it was just me and my little brother, I was seven – and we cried for a fortnight beforehand. We were sent to Wells in the West Country. It was a terrible billet, with a really terrible person. She had six of us there. We all shared one bed, top to tail. Six in a bed! After breakfast she’d send us out, with me in charge – at seven, I was the eldest – and say, ‘Don’t come back till dinner time.’ Then out you’d be sent again and be told not to be back till teatime. We all got fleas. And there was a centre where we had to report. They had a nit nurse – Nitty Nora – and, when they found we all had them, they said that the six of us had to come back the next day. We were so scared. Really terrified. Had no idea what to expect. None of our mums or dads were there, no one to talk to, to tell us what was happening. Why did they want us back there the next day? What were they going to do to us? So I didn’t take them. Instead, I just took them all off to Wells Cathedral and hid them. All day. We were so scared of what was going to happen. At the billet we’d been hit, so what should we expect now? Our parents didn’t even know where we were at this time.

If sending some children to stay with strangers far away seems like asking for trouble, and sending others to the coast seems foolish, then sending bombed-out East Enders only as far away as north-west London seems positively insane. Yet, close as it was to their homes, the reception they received there wasn’t always a lot better.

We were all just loaded on to red double-decker buses to start our journey, when the warning went off. Someone decided to carry on with the evacuation, so off we went. All the way from the Island to West Hampstead, German planes swooped down, machine-gunning the buses. Us kids were made to lie on the bus floor all the way. I saw no danger, it was like an adventure, and when else would I have been allowed to lie on the floor of a bus? I remember looking up and seeing Sam, an old man who had also lived in our street. The bombing must have driven him mad, because he did that ride all the way with a tea cosy on his head, convinced that nothing could harm him while he had it on. I laughed and was given a good clout for doing so. One of the buses in front of us had been shot at and had turned over, but all the drivers had been told not to stop. Whatever happened – keep on going. So our bus did and we never heard what happened to its passengers. Once more we were dumped in a hall. [G– and her family had just spent twenty-four hours in a church hall, having lost everything when their home had been bombed.] This time a school hall … in Kilburn that was to be our home for a few days until we were billeted out. We trooped off the buses across the school playground in double file into the lower hall of the school. This time it was luxury we found waiting for us, in the form of used mattresses that were laid across the entire hall at two-foot intervals. We were told to keep in our family groups, find a mattress and try to get some sleep. Lots to see, other people to watch. Families were trying to keep together, four to a mattress; larger families scrambling to get two mattresses together. I wanted to see this place we had come to, this place where they got no air raids. I ran to look out of the window, only to find blackness – sandbags had been stacked up outside each of the windows. I must have fallen asleep with my only possession, my doll [her father had risked his safety by rescuing it for his daughter from their bombed-out home], with people all around me clutching paper bags and small bundles containing all they had left in the world except their families. [My sister], whose husband was away in the army, was worried that he wouldn’t know where she was or how to find her. She had no nappies left for the baby and he, along with dozens of other babies, was crying and grizzly. We were assured that, ‘Tomorrow everything will be fine.’

That first night we spent in Kilburn – ‘The place that doesn’t have any air raids’ – the Germans bombed the hell out of the place. The building rocked, glass broke, and people were shouting and screaming. But not in our hall. We were all hardened to this. To us it was just another night like so many others. The minders, although trying not to show it, were much more frightened than us. Our Cockney humour came through – ‘Blimey, if this is the place they don’t get any bombs, someone’s having a good fart,’ said someone as another loud crash rocked the building.

There was only one inside toilet for us to use, so the men had to do a dash between the bombs to the outside toilets. There was no water to wash with. My long ringlets were caked down to my head with mud, dirt and dust from crawling out of our shelter [when the family were bombed out, now several days before] and I was beginning to itch! The following morning, in came the WVS with drinks, sandwiches and clothes, but this time accompanied by a barber. ‘You’ve all got fleas,’ we were told. ‘As there’s no water for hair washing or delousing, everyone gets a haircut. Kids first.’ My dad loved my long curly hair, and I don’t know who was more upset of the two of us when I came out of line with a straight cut – above the ears all round. My nan, who had long plaits wound round her ears like earphones, absolutely refused the haircut and took her long plaits with her to her grave. What a sight the rest of us must have looked with our new haircuts.

Between raids we were allowed out in the playground for exercise. The first time we went out there, a frightening sight and sound awaited us. The local Kilburn people were looking at us from the other side of the school railings. Word had got out about our fleas and unwashed state. ‘Send the dirty East Enders back, we don’t want them here!’ Dirt, rubbish and anything they could find was being thrown at us through the railings. ‘They’ve brought bombing here with them. We never had this before they came!’

In fact, they were right, the German planes did follow us up to Kilburn – machine-gunning us all the way and dropping their bombs for good measure before they returned to Germany.

Even if people didn’t meet such unkindness or hostility, the so-called Phoney or Bore War did lull civilians into a false sense of security and, as a result, many chose to take their children back home to the familiar streets of east London. The not unsurprising attitude began to prevail that it all seemed safe enough and, if the worst came to the worst and people did ‘cop it’, then at least they’d ‘all go together’. With minor variations in the actual words, this feeling was expressed to me many times over.

... the authorities thought gas would be a major weapon. My mother felt that, with a young family, she should take every precaution open to us, so we took off for Holland-on-Sea, where wet blankets were hung over each window to counteract the effects of poison gas. After a week of this futile operation, the curtains were removed, we returned to London and life returned to normal.

I had only been to St Luke’s School in West Ferry Road, Millwall, once or twice when I was being labelled and put into a charabanc and taken to a train somewhere. My next recollection is being the last child chosen from those in the group. I never have and never will get over that experience. The family wanted me as little as I wanted to be there with them. After a few months of this, and little or no bombing, my mum and dad came down to take me back home.

I was nine when the war broke out. For the first few weeks nothing happened, then we were all evacuated with our schools. My school went off to Hopton-on-Sea, two of my brothers went to Haywards Heath with their school, and another one went to Brighton, leaving one small brother and sister with Mum at home and four working brothers and Dad – we were a big family, as you can see. Well … we all came back to the East End. I loved being back in Stepney with the family. Everything seemed normal. We played in the streets and went to the parks with our older brothers. But then, after a couple of months, the sirens went off.

When the war started, I was sent off to my dad’s family in the north of England. But as we were not bombed or attacked, my mother took us home with the comment, ‘Oh well, if it happens we will all go together.’ As we now know, later all hell was let loose.

And it was that ‘hell’ – when the bombing began in earnest – that prompted another wave of evacuation. Not just children and mothers, but whole families were leaving London. And, not surprisingly, experiences were again mixed. The foster parents, as official leaflets and advertisements called the reception families, were again shocked by the inadequate clothes and footwear of the poorer children, and the sometimes impenetrable Cockney accents and the cursing of the ‘rougher’ youngsters were harsh on country ears.

As for the East Enders, some of them were similarly appalled, although it was the lack of cinemas, the infrequency of the buses and the fact that there wasn’t even a local branch of Woolworth’s to pop into that upset them. Going ‘hopping down in Kent’ for a couple of weeks a year was one thing, but being expected to actually live out in the sticks as a full-time proposition was quite another. Not only was there the culture clash between two groups with very different interests and expectations, but it was at a time when most East Enders didn’t have a car they could jump into to get away from the place whenever they felt like it. They probably wouldn’t have been able to get hold of the petrol even if they did have one.

The Blitz had begun and, because of the incessant bombardment, my mother thought it was time to seek refuge elsewhere. She chose Hertfordshire, where my maternal gran and aunt had taken a bolt-hole in two rooms in a house. We found two rooms in a nominated billet around the corner and, with our frugal belongings, arrived bedraggled and forlorn to a chilly reception by the house owner. The next morning revealed I had come out in spots – measles. Our hostess-with-the-mostest threw us out on the spot – sorry about the pun! – and there we were: Mum and two little girls, plus shabby belongings, on the grass verge for all to deride. I remember my sister putting me into an ancient pram someone had brought forward, declaring, ‘This is no place for you, you’re not at all well.’ My mother and grandmother were so incensed by the attitude of the billeting officer of Hungarian origin, whom my grandma decided must be a German, that an angry altercation took place. This was only brought to a halt by a young woman called Muriel, who was seven months pregnant, with two other children. She ran on to the scene with pinny flying to offer her home to us three without question. For someone in a three-bedroom council house with 2.5 children, this was a true Samaritan act, and we lived happily together for some twelve months. During this time her baby was born, a little girl named after [us], the Cockney lodgers, and we’d found a firm friend at our darkest hour. It was also during this sojourn that we learned we had lost our home and the shop – at the drop of one bomb, our home and livelihood disappeared. This was the only time I saw my mum cry. She fought back, though, and the next day took us to the photographers, all decked out in dresses made out of some redundant curtains, to have our picture taken for Dad, with the message written boldly on the back, ‘We’re still here!’

Even the journey out of London was exhausting for those already battered by nightly bombardments.

An open-top lorry arrived the next day to take us and all our things to the place in the Essex countryside Dad had got us. We got on the back and sat on our chairs. As we drove through Ongar, my eldest sister, who was wearing a halo hat, had it taken off by a tree as we passed. We had been told beforehand that we had to help take things into the cottage directly we got there. When Father helped us off the lorry, we couldn’t stand up we were so cold. The beds couldn’t go up the cottage stairs, so we had to sleep on the floor until Dad cut the springs in half and then bolted them back together after getting them into the bedrooms.

At least that family managed to stay together. It is hard to imagine how torn parents must have felt between wanting their children to be somewhere safe and yet not wanting to be separated from them at such a terrible time. One little girl struggled to protect her small brother from the harsh treatment they received at the hands of the family with whom they were placed before being moved when her parents finally discovered the reality of their children’s situation. Their new billet, in the second wave of evacuation, was with ‘a lovely old couple’ and the two youngsters were able to share the experience of those fortunate children who had found warm welcomes and kindness from the beginning of their time away from home.

The following memory carries a rather mixed message about what one child experienced.

At the age of ten I can recall my mother packing my things in a borrowed case and going with me to the school, where we were assembled, labelled and sent off to the railway station, [then] off to a small village near Cambridge. Really, I was lucky to be lodged at H–’s Farm, with a family made up of a middle-aged couple, the owners of the farm, and two very old grandmothers, one of which took more or less charge of myself and a boy called Smith … The farm was wonderful to someone like me, coming from a small place in the heart of London, familiar only with a very tiny back garden and one small pet dog … We were surrounded by orchards of every description, farmlands and stables, pigs and all kinds of other livestock, which made me wonder if I had come to a super zoo.

My two nephews, Harry and Siddy S–, were installed in a nearby farm, and my other nephew, Siddy N–, was in a small house with a farm labourer’s family, also within a short distance … [We all had] the freedom of the place and assisted him in the feeding of the animals. Especially, we enjoyed the pigs, whether mucking them out or preparing the awful mixtures they ate; or catching the goats to be milked. We would turn their filled teats and, with a quick squeeze, catch one of our friends full in the face, or in an opened mouth, with a jet of warm creamy milk. There was the wonder of sitting astride one of the shire horses and feeding the goats, geese, hens and rabbits, and all the other farm activities that were so new to us.

Opposite the farm were the huge open pits of the cement works – a playground full of danger, about which we were many times warned – but we loved the place and never came to any real harm, apart from returning to a scolding when we were covered from head to foot in chalk and cement dust.

Whilst with the H–s we were well looked after, and I really loved the freedom to wander amongst the orchards and to climb trees overladen with fruit of the most delicious kinds. Often I would sit in a tree observing the activities of the nearby RAF air base, whilst eating my fill of fruit. One autumn, there was so much fruit that we staggered to school laden with sacks of pears, apples and plums to be given out in class to the other kids. Of course, this gave us a certain prestige that we enjoyed.

The old granny did so much for us, and sometimes used to fetch a huge tray of baked apples, or monster-sized fruit pies, from which we helped ourselves. But I cannot recall ever eating with the rest of the family.

That final line of the quote might startle the more cosseted individuals we are today – it certainly made me wonder if I had understood correctly – but what is impressive is the astonishingly good heart, or maybe sometimes the weary resignation, with which such tales were related. But there were some things that people still regarded as too painful to discuss, even all these years later. As an almost throwaway comment, for instance, I was told, ‘When my cousin was evacuated, he had a label around his neck saying, “Bed Wetter”’. When I investigated a bit further, I discovered that this was considered a major enough problem for official pleas to be made to foster families to accept this understandable shortcoming in their frightened little guests and not to punish them, otherwise it would make matters worse. But such was the alarm of the families – maybe partly defensible in those days before automatic washing machines and tumble driers – that the authorities eventually had to agree to set up special hostels for children with bed-wetting problems. Despite trying to find people who would be prepared to speak about their experiences of staying in such a place, I was unable to do so. Perhaps they have chosen to forget it, or just don’t want to recall such unhappy memories.

Some unusual experiences, however, were recalled with pleasure. These are the recollections of an East Ender who was evacuated to far-distant Wiltshire. In addition to her surprise at the rural environment, she also speaks of encounters that, to an eleven-year-old kid, were entertainingly exotic.

We had two POW camps, one for Italian, the other for German prisoners. Both were within a short distance of each other, and my friend J– and I would often walk up to where the camps were to look at them. Of course, we couldn’t get near to them. They were well guarded. The camps were surrounded by wire, a gap of about six feet and then another fence of barbed wire, but higher than the inner one. A grass bank to the side of the road allowed us a good view. We would wave to the prisoners, call out to them, and generally make a nuisance of ourselves to the British guarding them. All [the POWs] did was walk round and round the compound, some in groups, some alone. They looked bored and harmless – a ‘what am I doing here?’ look on their faces. Some waved back, some turned their backs on us. Some shouted at us in German, some in English. The only difference I could see in these men was that the Germans were in a dark grey, the Italians in brown. There was one other big difference – the Italians in their brown gear were allowed out during the day to work on the local farms.

The same former evacuee went on to remember how she met other foreigners who were also away from home and living in the English countryside, but for very different reasons.

We had another camp [nearby] but this one was quite different from the other two. This one was an American base, music, laughter and freedom being the only difference I could see. The men looked just as young, they looked just as bored – why shouldn’t they? There was nothing for them to do. The Vista – two Nissen huts joined together – was soon erected and became the local cinema. Now, Nissen huts have tin roofs, so when it rained nobody could hear what was being said on the screen. But it changed programmes three times a week and was very busy. For the Yanks who had a day pass, there was no way they could make it back to camp by ten o’clock as the [timing of] the last of the two-a-day-only buses meant they couldn’t spend the evening there. One Sunday, in chapel, an American bigwig got up after evensong and asked for the community’s help. ‘These boys are young and homesick, some of them never being away from their families before. They’re in a strange land, waiting to go overseas, and they’re afraid,’ he said. ‘Could the ladies of [the village] and their families do anything, come up with any suggestions, to make them more welcome, same as they would like their sons to be looked after in a strange country?’ This struck home, the people were having their consciences played on, and a meeting was called of the Women’s Guild after the service. One suggestion was to have a soldier to dinner on Sundays. Those that were willing put their names in a bag. The soldiers who wanted to go put their names in a hat. The idea was that one name was picked from each – that was the family he got, that was the soldier you got. Next week all names went back in for another selection. My aunt put her name in the bag, then proceeded to march us all – my uncle, my cousin Billy and myself – like her own private army, back home. All the way she was muttering, ‘That’s all very well, but where’s the food coming from? I suppose they do know we’re on rations. God knows what I’m going to give them to eat. I just hope they don’t expect anything fancy, that’s all.’ But none of us reckoned with the Yanks. We had many soldiers to dinner. Every one of them brought something with them. I don’t know how they got it – be it a bottle of something, to a side of ham; a packet of cigarettes, to tins of pressed meat; and, wonder of wonders – dried eggs – tins and tins of it. I’d already been treated to several sticks of gum and candy bars by them in the streets – ‘Here, kid, have a candy bar’ – but now dried egg! It was smashing.

Just as evacuees gave varying accounts of the warmth or otherwise of the reception offered to them by their new ‘families’, so their experiences of meeting foreigners could also vary.

I was with some friends on the bridge over the stream that ran through part of the village [where we were evacuated] when I first cast eyes upon some big American soldiers. We scrounged some chewing gum from them – ‘Got any gum, chum?’ One of them produced a nasty-looking knife and I asked him what it was for. He said, ‘For cutting off little boys’ heads’. I was very frightened and when they asked us if we had any sisters at home we took the opportunity to run off home. Thank goodness I did not know what they meant.

It wasn’t only the foreigners who provided strange, new experiences for Cockney youngsters. Household arrangements could prove equally exotic and even baffling to the little townies.

I was evacuated in the first year of the war to a middle-class family in Swindon. The house had an indoor toilet and a bath! She also had a vacuum cleaner, a sewing machine, a dog and cat, and two children at college. They were very good to us – outings on Sundays, Women’s Institute activities and Sunday School. She bought us coats with real fur collars.

Then came the sad postscript that the woman who had been so kind to this evacuee had committed suicide – presumably as the result of some war-related tragedy – and the children had to return home to London. But the reason that most young Cockneys were called home was the end of the Blitz.

Following that drift back to the familiar streets of the East End, there was yet another move to evacuate Londoners – when the dreaded V1, or ‘doodlebug’, raids began. As before, it was all down to chance where you wound up, and with whom.

I’d had my second baby, my mum had died and my mother-in-law had been killed when a bomb fell on her house, and the V1s had started dropping over London. When my husband was due to go back after his leave, he was afraid for us, so he found me and my cousin D– a place near Folkestone. It wasn’t that far away, but we had a better life even though we did not have gas or electricity. We cooked by coal fire, which had an oven, and there was plenty to eat. The farmer used to leave us vegetables of all kinds on our step.

I went back to London to see how my dad and family were. Dad had my younger sister S– living with him then – she was expecting a baby. The bombing was so bad, with the V1s, that I made her go back to Kent with me and my cousin. And she had a little girl to think about. But I remember one lovely Christmas there when we were all together. My dad and sister Kit came with my brother Tom and his wife – another Dolly. All our husbands were on leave and Tom and Dolly brought a duck with them, which they sat and plucked. Then we all went to the pub – the only one down there for miles – and we got all the country folks going with a knees-up! My husband’s sister won a rabbit, I had a chicken, and we ended up with a really good dinner, using the coal fire and all sorts of oil-fired gadgets. My sister had her baby there – we managed by boiling the hot water in saucepans for the midwife. Her baby was christened down there, as was mine at the same time. Our churches back in London had been blasted by bombs before I’d left, and I hadn’t been able to have him christened until then, so we had the christenings in Swingfield in Kent, with RAF fellows for godfathers.

For children going away without their parents, having at least some family ties in an area – no matter how distant – could make an otherwise daunting wartime experience that bit more reassuring.

It was during this [time] that it was decided I should be evacuated. Welfare workers were asking mothers to go to the country with their children, or to let the children go on their own. My dad and nan were made to feel guilty and selfish for not wanting me to go. I didn’t mind going. We had distant relations that lived in [the country]. I couldn’t remember them, but it was decided if I had to go, I would be best off with family.

Off I went with my best friend, B–, who I had convinced to come with me. We left Paddington Station with our labels attached to our coats saying who we were and who we were to go with, our gas masks and one small parcel of clothes. There were lots of tears that day. Parents were not encouraged to come to the station, so goodbyes had to be said as we left the school playground to get on our allotted buses. Parents were changing their minds and pulling kids back at the last minute; others were pushing their screaming kids into the buses and running away home. By the time we got to Paddington, most of them had calmed down and were looking forward to their trip to the country … I was quite relaxed but B–, not knowing where she was going or with whom she was to live, was a bit nervous, but we had vowed not to be parted and went everywhere with our arms linked in defiance of anyone trying to separate us.

We arrived [in the country] with kids from all over London who had joined us at Paddington. A bus took us from the station to the school. Another hall! [She had already spent a lot of time in various halls used as rest centres after her family had been bombed out.] We stood in rows and were told, ‘Smarten yourselves up.’ How? The village people were then let in to look us over, to see who they fancied taking in. They walked up and down the rows of us sorry-looking sights and then back again until they made up their minds. This did not really bother me or B–, as we knew we were being called for by my aunt, but we had to stand in line just the same. I saw brothers and sisters being split up because people only had either sons or daughters that the evacuated children would have to share with. Two brothers were split because the five-year-old was sweet and quiet, while his brother was a proper Just William type and so the mother said no to the elder boy. Yet some were very kind. One woman, a farmer’s wife, had come to take two boys and ended up taking a whole family of three boys and two girls whose ages were from five to thirteen. ‘Oh well, what’s a couple more,’ she said. ‘We’ll manage somehow.’ The hall was almost empty that Saturday afternoon, save for two or three kids who were sitting on their parcels looking lost and still hoping someone would take them, when my Aunt Bessie strode in, handbag on her arm, sensible shoes on her feet, and her clean cross-over apron wrapped around her. A small, bird-like woman with piercing eyes, she saw me, came over and gave me a hug, and said, ‘Come on, young ’un.’ I stood firm. ‘This is my friend B– and she wants to come with me, she’s my very best friend and we won’t play you up, honest.’ She looked at B-, back at me, linked one arm in mine and one arm in B-’s, then said, ‘Well, we’d better get going then or the men will be in for their tea.’

Three abreast, we walked that long walk back to my aunt’s, with her asking questions about the family, the train journey, everything – but no mention of the war or bombs. The men, being my uncle who worked on the railway, and my cousin Billy, eighteen and training to be a carpenter, were not in, so we were shown all over the big house, shown our bedroom, which overlooked the orchard, and were left to unpack our small parcels before coming down to tea. We spent the next half-hour opening cupboards and drawers, looking out to the orchard, where we could see a horse eating the windfall apples, and giggling on the big feather bed. It was smashing – we both agreed.

We went down to the large kitchen with its big table in the middle of the room. We were told to take the two back seats. ‘They’ll be your seats now,’ we were told. She walked into a big cupboard we later discovered was the larder, and out came fresh-baked bread, pots of home-made jam and a big home-made chocolate cake. Aunt Bessie laid five plates in position. ‘This will be your job from now on – to lay the table and in these places.’ We were knocking knees under the table and ogling the chocolate cake. Billy and Uncle came in, having put their bikes in the shed.

‘Hello, who you got here, then?’ said Uncle. ‘And who’s this, then?’

‘That’s B–. She’s –’s [my] friend. I’ve put them in the girls’ room.’

The girls were my cousins, Gwen and Phyllis, who both lived away from home. Gwen was in service and Phyllis worked in a munitions factory in Salisbury and only got home occasionally.

The meal finished, Uncle took us to see the chickens, told us we would collect the eggs daily for him, and showed us where the gin traps were so we wouldn’t step on them. ‘They be only for rats, not little ’uns’ feet,’ he said.

‘It’s all very well telling us we can collect them eggs,’ B– said later, ‘but I’m not all that sure about going in there with them chickens. Say they fly out?’

I couldn’t answer because I didn’t know, so I just shrugged my shoulders. Within one week we were collecting eggs, feeding the fowls, mucking out pigsties and herding cows like we were born to it. We were given one week to get used to our new home and find our way around, and then it was back to school. A school bus brought children to the school from all the surrounding villages, [but] we had to walk as we didn’t live far enough away. Our school playground was a large field. If the horse, Roofless, was not earning his keep, we were allowed to ride him to school and leave him in the field during lessons. Going to school on Roofless’s back became a usual thing for the two of us.

After we’d been in the village for about three months, B–’s sister, Vera, who had met and married a Canadian airman during the war, came to visit and see if B– was OK. After she left, B– was not the same. I think her sister’s visit had unsettled her. She got homesick, she cried a lot and, unbeknown to anyone, wrote to her mother to come and take her home. Once again the sister visited us, brought letters and a parcel from home for me and asked if I wanted to go back. ‘No,’ I said, ‘I want to stay.’ I loved the life there. The same day, B–’s things were packed and she and her sister caught the six o’clock train for London. It felt strange at first, but I can honestly say I didn’t mind.

If, as for young B– above, it proved too much for children to have to live in a strange place and away from their families, returning to the East End could also be a problem, even a shock, after having had a taste of how other people lived.

We’d been put with a really terrible person first of all. Wicked. But then we’d been billeted with a really lovely couple, and their house was lovely and they had orchards and everything. We were really happy there. For the first time in our lives, my brother and I had a money box each. They used to give us thru’penny bits and their change and that. And we had more than one pair of shabby shoes. It was real luxury. The family had two grown-up daughters who were courting but who looked after us. We were spoilt rotten for the first time. I loved it. We were there for six, seven months. When the daughters married we had to come home, as there was no one [left there] to look after us. Really, we didn’t want to go back home. And, believe it or not, back in the East End, we had the real mickey taken out of us because they said we’d come back talking posh!

It wasn’t only a bit of teasing that the children returning would have to cope with. They were coming back to a place with no orchards full of apples and plums, no abundance of new-laid eggs to be collected every morning, no fresh air or pony rides. They were coming back to their families but also to a world of shortages, bomb sites and restrictions.