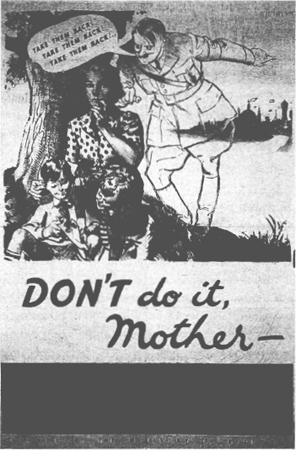

[ 10 ] Family Separation and Loss

The thing that stands out in my memory is of a long train carrying troops – my husband amongst them – and me standing at St Pancras station waiting for him. Lovely when he was coming home on leave, but so sad when he was going back.

It wasn’t just being called up for the services or for civilian war work in another part of the country that could separate you from your loved ones. This woman remembers a wartime childhood in which she not only lost her home when it was reduced to rubble by a bombing raid, but was then taken away from her neighbourhood and herded from one reception centre to another. The authorities and hard-working volunteers tried to do their best for her and her family, but they were still obliged to stay – camp out, almost – in what were essentially bleak, inhospitable halls requisitioned from schools and churches. And, when her family were eventually found somewhere more permanent, she then suffered the additional loss of being separated from her mother and sister.

The next day there were more tears. We – our family – were being split up. My mother, now remarried, with her two-year-old baby daughter and my sister with her baby son were told that a clippie* in Netherwood Street would let them have her back bedroom and share the kitchen while her husband was away in the army. The parting came with many tears and hopes that we – Nan, Dad and me – would not be billeted far from them, and vows of seeing them as soon as we could. We got billeted at West Hampstead with a Mrs I-. She had a ground-floor flat there and was willing to let us have her back room. Her husband was away in the air force, and she lived there with her baby son. We were taken there by car and it seemed miles away from where my sister was, in Kilburn – which caused more tears.

‘We’ve just got to make the best of it,’ Dad said, as we looked around our large but unfriendly room. It had one big double bed, a table and some chairs, a chest of drawers – that we had nothing to put in [as everything had been lost in the bombing] – and a big built-in-the-wall cupboard. This cupboard was to be our shelter, Mrs I– explained. She slept with her son in a cupboard under the stairs during the air raids, as she had no shelter, and that cupboard of ours, she assured us, was as safe as houses. Safe as houses?! [Her family home had just been flattened by a bomb.] From our window the garden ran straight down to the railway lines, and as railway lines seemed to be the next hitting point for the German bombers, we spent many more nights with bombs dropping all around us. Dad took the mattress off the bed and put it on the cupboard floor, and there we slept night after night. I was OK, being only small I was inside, but Dad and Nan were only in it up to their waists. ‘Well, if they drop a bomb on us now, Mother, we’ll be legless!’ Dad joked.

We found where my sister and mum were and did the long walk from West Hampstead to Kilburn most days, sometimes while a raid was going on. I saw enemy planes fighting with our planes and bombs actually leaving the bomb carriage of German planes many times on that walk to Kilburn. ‘If it’s not got our number on that bomb, we’ll be all right,’ Dad used to say, and still we kept walking. Come to think of it, what else could we have done? There was nowhere to take cover anyway. And how could you tell what number was on them? They fell so fast. And I didn’t know what our number was anyway. Unless, I thought, it was my identity number.

My sister and mum were quite comfortable with Blanche, the clippie. She was friendly to them, and us, when we called around – unlike Mrs I –, who insisted we kept ourselves to ourselves, and only mixed and talked with us when absolutely necessary. Dad pestered the WVS to find us a place of our own, nearer the rest of the family. ‘We’re a family and we don’t want old Adolf to part us now,’ Dad told them.

Families from our street weren’t exactly spoiled for choice when it came to what they could do and where they could go following the loss of their homes in the bombing. The issue was usually settled pragmatically and, to put it bluntly, they had very little say in the matter. But most people realized that if they were to keep their head during those difficult times, they would have to do what they could and make the best of things.

One woman spoke of having to take shelter in Aldgate when an early-evening raid damaged the workshop where she was employed as a machinist. She reached home many hours later, in the thick of the blackout, to find her family home had also been bombed – in fact, razed to the ground. Frantic for news of her family, she ran up and down the street in the dark until she came across someone picking through the remains of their equally devastated home, searching for anything that might not be damaged. The neighbour was able to tell her that her mother and sisters had put what was left of their belongings into a borrowed pram and had gone looking for lodgings a few turnings away, where someone had said that a woman had a couple of rooms available. It was the first time her family had left the street in which every one of them had been born, the first time they had not lived in the same street as her aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents. It is hard to imagine, with the geographical mobility available to us today, the shock and wrench of such a separation.

Some less fortunate individuals didn’t even have the benefit of those limited choices – about where they lived and from whom they were separated.

My father went into the army, my mother had to do war work in a factory, and it was decided I was to be evacuated. I did not go with the school but went privately for ten shillings per week. Our rent for the house was a pound and money was very short for Mum. Before I was evacuated, to help out with the housekeeping, Mum took in a lodger, W–, a sixteen-year-old German Jewish boy who had managed to get away from Germany just before his family were sent to the concentration camps. He settled down well and to me he was a big brother. But he was interned and ended up being sent to Australia.

Sadly, even for previously very close families, separation could sometimes become permanent, as close-knit bonds unravelled due to enforced relocation following enemy action and the demands of war.

What with the bombing, evacuation and the need to change jobs, families and neighbours in the East End were split. Many never renewed contacts or went back to live in the close family units that prevailed before the war. My uncle, who lived opposite us in Bow, had to leave after the bomb hit our houses. He ended up in north London. During my childhood and up until the bombing, he had called in to see my mother practically every day. After he moved he was seldom seen.

You have to realize that we didn’t have phones and the computers like you do now, or the cars to get around as you felt like it. A few miles was like the other side of the world. Anything more than a few turnings away was as good as being abroad.

It is easy enough to be fearful at any time when you have been forcibly separated from loved ones, wondering if they are well and safe and happy, but during wartime those fears are elevated to new levels, as you are all too aware of the dangers they might be facing.

... there were couples who were separated for years. Some husbands, fathers and sons were taken prisoners of war right at the beginning and had to spend the whole war in prison camps. I can’t imagine what that must have been like. It was bad enough Ron being in the Middle East for three and a half years.

Separation was one of the hardest things in the war. Our family were all in different places: my mum was at home; my dad, a dredging engineer with the Merchant Navy who was seconded to the Royal Navy; my brother evacuated to Wales; and myself in the WRNS. Just before D-Day my mother was frantic, because neither my father nor I could be in touch with her. My mum used to ring me every week from the telephone box on the corner of our road, so when she rang and did not get through she didn’t know what to think.

It was because most homes didn’t have telephones that letters were still the routine means of keeping in touch. And while the sight of the telegram boy was feared because of the bad news he was sure to be bringing to your doorstep, a visit from the postman was always welcome, as he just might be bringing you news of your loved one. Whether it was from your husband, boyfriend, brother, son or maybe even your daughter, and even if it was telling you all leave was cancelled, at least you knew they were all right. Well, up until the time they had written that last letter …

You tried to cope with the separation by living for letters, writing them all the time. Sometimes you had to wait weeks to get one.

I worked at Blackfriars for a good few of the war years and when there were delayed-action bombs dropped we used to have to work on invoices etc. in the back of the company’s lorries. The company manufactured paint that was used on ships, planes, tanks and so on. We backed on to the River Thames, and there was a flat roof where we could go up and eat our sandwiches at lunchtime, and I could sit and write my love letters. They would begin, ‘Darling, I am on the roof looking out on the Thames and writing to send my love all to you, tucked in this envelope.’

The shock, followed by denial and then the pain of realization, and then the months and probably years of mourning, experienced by those people who would never get another letter was always there as a possibility, hanging in the background whenever your loved ones were away. But it still seemed so unfair, so wrong, when it happened. Having gone through so much already – what with the bombing, the fear and the uncertainty – they were now having to pay the ‘ultimate price’ of permanent separation.

A single bed was put in my room alongside the double bed. My aunt said I was to sleep in the single bed as my cousin Phyllis was coming home. Poor Phyllis, her boyfriend had been killed in action, and she had been given a few days off [from the munitions factory]. She cried herself to sleep for three nights. I crept out of the single bed in beside her in the double and we cuddled up until she cried herself to sleep.

R– was to become a pilot in the RAF and, sadly, lose his life.

There was the awful dread of seeing the telegram boy. You knew it was bad news for some poor soul.

[My brother] was, in my eyes, a great guy with an outstanding personality. He would date all the girls, but made a lot of fuss of our beloved mother and would be seen accompanying Mum and Dad into their local for their once-a-week drink. When the call-up came, she took it deeply to heart that her boys were to go to war. [My brother] never failed to write great letters, full of humour to boost her morale when times were low. I believe his letters, above all else, were the tonic she so needed. Sadly, he was the son not to come back. I still feel the grief as I write this. It was to change her life for ever. She deserved so much more. Her life, her very existence, was for us, her family. [My brother] to die at twenty-two years of age was to be our biggest family tragedy.

V– was to go to France with the British Expeditionary Force and disaster was to strike the family. He went missing. Most of the soldiers were back via Dunkirk but alas no news of V–. There was a death knell over our house, but he was to arrive home unannounced. Apparently his platoon was cut off at Dunkirk but he managed to drive along to Brest, which at the time was surrounded by Germans, where he boarded a merchant ship and managed to get home with all his equipment. There was joy at home and celebrating into the early hours – the favourite son was home – but sadly the joy was to be short-lived. V– was to go abroad again with the 8th Army to Africa. His letters would continue to flow and provide real morale boosters to all of us. The letters contained no complaints. As I get older I find there is little time to spare, it simply flies by, but in those days, with three brothers abroad in the army, we at home seemed to live in limbo land and time stood still. Tragedy was to strike finally. V– was taken prisoner in Tobruk whilst serving in the 8th Army. We received no word until, to our relief, one post saying he was a prisoner of war with the Italians in Benghazi. There was total relief in the family, but, again, silence. V–’s closest friend, S–, was to turn up in the Ship – the public house opposite our home. He would not come to the house to give the tragic news. He had been on board the prison ship with V–. There were 500 troops battened down below. There was no Red Cross flag. S– was taken for his stint of air on deck. A British submarine fired over the bows of the ship, signalling to heave to. The ship started to run the gauntlet [and] the submarine sank the ship. There were only seventeen survivors, including eleven crew. S– survived because he just happened to be on deck. The tragedy was called ‘The Missing Five Hundred’. We got the tragic news that night from S– and it appeared in the Evening News with V–’s picture. S– had obviously given the story. This sad event was to alter our whole concept of family life as we knew it. It would have been far better if Mum had had a nervous breakdown, but no, she was to carry on for the sake of us all. [It was] as if half of her had died along with him.

One of my father’s brothers, L–, was killed in the jungle wars with the Japanese in Burma. He was just twenty years of age at the time and is buried in one of the vast cemeteries near Rangoon. No one in the family had known where and how he died, [but] I found out that L– was a member of the famous Chindits and was killed along with thousands of others in the most horrific circumstances. I don’t suppose for one minute that he, or other youngsters like him, realized the dangers.

Such tragic stories cannot help but touch us – not least because of the youth of those involved. And as this was a war that put civilians in the firing line, there are equally tragic stories from there too, right on the home front, in the middle of our street.

... how we survived seemed a miracle, when every morning on your way to work you saw the terrible devastation, and men digging under the rubble hoping to find some survivors. Thank God some of us survived, but thousands didn’t, and our hearts went out to the families that lost their loved ones. I lost some of my friends. One, on his way home from work, was literally blown to pieces by a land mine, only because that night he had to take the shop’s takings round to his manager’s house, which was in the opposite direction to his normal route back home. The land mine dropped and blew him to smithereens. His wife was left with a little boy of three years old. She never married again. Then, less than a month later, the police came to her door and told her a bomb had gone off in the underground. They had found a body with her address in his pocket. She ended up identifying her husband’s brother, who was dead, his wife, who had been critically injured, his mother, who was just about alive but who had had her leg blown off, and his little five-year-old daughter, who was also dead. Soon the whole family was gone. Another friend, whose husband was on leave, came out of the shelter during a lull and went indoors, probably to make a cup of tea, and the house got a direct hit. They were both killed. She was expecting their first baby.

A young member of my family – he was twenty-six – was in an exempt job. He was helping the wardens when a land mine fell nearby and he was crushed by the wall of a shop falling on him. When he was taken to the mortuary, his age was stated as being about sixty years, so he must have died a terrifying death. Six weeks after he died, a letter arrived telling him he was no longer in a reserved occupation and would be called up. Who knows, perhaps if he had gone into the services earlier on he may have lived.

Living and working close to the Thames was one of the most dangerous places of all for civilians.

Her three brothers and her father worked as lightermen in the docks, two on one shift and two on the other. One day they were on the barge, changing shifts, when the barge had a direct hit with a bomb. They were all killed. It was so sad.

It was Saturday and Sunday night under the Morrison for us. [The bombing] was so bad on the Sunday night that my father said I was not to go to school, but he had to go to work. I went up to lie on the bed. I was quite bad-tempered, because I’m awful if I haven’t slept. My mother went to lie on the couch in the sitting room and [her father] rode off to work on his bike. People told us afterwards that every morning he would always get off and look at the boats. We didn’t know that. After a bit there was this great wooooooofff! The ceilings came down, the windows came in, the door evidently just missed my mother and she came and screamed at me, ‘Are you all right?’ I walked to her over the rubble and she said, ‘Get dressed and I’ll go and ring your father.’ There was only the pub that had a phone, and she went down and phoned [his firm] and said, ‘Will you tell my husband that we’re all right?’ And they said, ‘He’s not here yet.’ And she said, ‘Oh, that’s funny, he should be. Anyway, he’ll be there in a minute.’ So she came back, and I can remember that she said [her father’s name] all of a sudden and ran out down to the river. She knew what had happened and I ran after her. My mother found him. He was lying there on that piece of the shore … As I got there, an ARP man was just coming up to Mum [and he] put his arms round her, saying, ‘There’s nothing you can do for him.’ My dad had been killed by the blast, and, you know, he looked perfectly all right, but my mother said afterwards that his neck must have been broken, because it was at an angle. And I remember that my friend A–, who lived in the flats behind – evidently this thing, so people told us, had been coming towards our houses, and it had caught these flats and they’d gone to powder. A–’s brother, who was on his paper round, had seen this happen, and had seen where his parents had gone. They were dug out because he was able to direct them in, so his father and mother were in hospital. A– was all right, [but] they’d lost their home. Old Mr L– and Mrs L– were killed, and young N– and his father and mother and the new baby were killed, and young K– downstairs and her father were killed. She was eighteen, a pretty girl. I can’t remember who else – people on the riverfront. That really was the end of a whole chapter. Our lives changed completely.

Despite so much sadness, there was also good news for some, with the long years of separation at an end – for the time being, at least.

I was on a little break from work in London, staying with my aunt and uncle at their home near Oxford, and my young brother, who was seventeen, made the train journey from London – Gran paid his fare – to bring me a card from the army. It said in bold print, ‘I AM COMING HOME. Do not write any more until you hear from me.’ And it was filled in by my Jack! Remember, we hadn’t seen each other for three and a half years. I packed my bag and caught the next train home, pinching myself – was it true?