Chapter 3

The twins descended the stairs from their room on the second floor, Raistlin leaning on both his brother and the staff, the black wood resounding hollowly. Moving around the huge open fire in the main hall, they went to the dining room. But before Caramon could enter, Raistlin stopped him, drawing his hood back to expose one ear.

The fighter recognized this signal—a sign the twins had developed over the years—and quickly ducked back around the corner of the doorway before any of the patrons could notice him. He cocked his ear, listening, hoping to discover what his brother found so interesting. Voices wafted like mist from the room.

“Tis the work of evil, I say!”

“Aye, it’s true!”

“I’ve lived eighty years,” interjected an old man, “and I’ve seen nothing like it! Always we’ve taken care of the cats, as the legend says. And now they’ve left us! Doom will fall on our heads!”

“Probably the work of some foul wizard.”

“Never did trust them.”

“Yeah! Burn ’em all up, I say! Like in the old days.”

“What do you think will happen to Mereklar, then, old man?”

“Mereklar? I fear for the world!”

“I heard there’re no cats at all left in the city,” stated a man, wearing a farmer’s smock and broad-brimmed hat. “Is that true?”

“There are a few left, a hundred or so, perhaps,” said the old man.

“A hundred where there used to be a thousand,” added another.

“And their numbers dwindle daily.”

Everyone began to talk at once, adding rumors they’d heard. They were beginning to work themselves into a frenzy.

Caramon came out from his hiding place to join his brother. He plucked Raistlin’s sleeve.

“I think we’ve wandered into an asylum,” he whispered loudly. “These people are crazy! To get this worked up over a bunch of cats!”

“Hush, Caramon. You should take this matter seriously. I would guess that this has much to do with the job we are seeking.”

“We’re being hired to look for lost cats?” Caramon began to laugh, his booming baritone roaring through the inn. Everyone fell silent, glaring at the brothers with baleful looks.

“Remember, Caramon!” Raistlin closed his thin-fingered hand over his brother’s thick arm. “Someone tried to kill us over it, as well.”

Caramon’s laugh sobered quickly. The two entered the room. Their presence was not welcome. They were outsiders, intruding on a fear they could not understand. No one said a word, no one bade them sit down.

“Hey! Raistlin! Caramon! Over here!” Earwig’s shrill voice split the sullen silence.

The twins walked to the back of the room. The inn’s patrons cast furtive glances at the mage, and there was whispering and shaking of heads and glowering scowls. Raistlin ignored them all with a disdainful air and a slight sneering curl of his lips.

Caramon helped his brother sit down and get as comfortable as possible on the hard, wooden bench. The warrior beckoned to one of the barmaids, who—after a nod from Yost—came over to the table.

Caramon sniffed at the air and wrinkled his nose, not liking much what he smelled cooking.

“Rabbit stew,” said the woman. “Take it or leave it.”

“I’ll take it,” said Caramon, thinking regretfully of Otik’s spiced potatoes at the Inn of the Last Home. He looked at his brother. Raistlin covered his mouth with a cloth and shook his head.

“My brother will have some white wine. Do you want something, Earwig?”

“Oh, no, thanks, Caramon. I ate already. You see, there was this plate of stew, just sitting there. My mother always said it was a sin to waste food. ‘People in Solamnia are starving,’ she’d say. So, to help the starving people in Solamnia, I ate the stew. Although just how that helps them I’m not certain. Do you know, Caramon?”

Caramon didn’t. The barmaid hurried off and returned shortly with a plate of food and a mug of ale, which she slapped down in front of Caramon, and a goblet of wine for Raistlin.

Caramon plunged into his dinner with gusto, slurping and chewing and shoveling rapidly. Earwig observed him in round-eyed admiration. Raistlin was watching with disgust when suddenly the mage’s attention focused on Caramon’s half-empty plate.

“Let me see that!” he said, snatching it away.

“Hey! I wasn’t finished! I—”

“You are now,” said Raistlin coldly, scrapping the rest of the food onto the floor.

“What is it? Show me!” Earwig scrambled around to sit beside the mage.

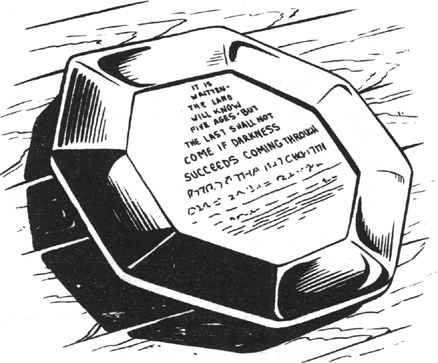

“It’s a poem,” said Raistlin, gazing at the surface of the plate with interest.

“A poem!” Caramon growled. “You ruined my dinner for a poem!”

Raistlin read it to himself, then handed it over to his brother.

It is written, the land will know five ages,

but the last shall not come if darkness

succeeds, coming through the gate.

Darkness sends its agents, stealthy

and black, to find the gate, to

be there when the time arrives

The cats alive are the turning

stone, they decide the fate,

darkness or light, in the

city that stands before

the first gods.

“Well?” said Raistlin.

“Cats, again,” answered Caramon, handing the plate back.

“Yes,” Raistlin murmured, “cats again.”

“Do you understand it?”

“Not entirely. Up to now, there have been four ages—the Age of Dreams, the Age of Light, the Age of Might, and the Age of Darkness, which we are in now. A new age coming …”

“But not ‘if darkness succeeds,’ ” said Caramon, reading the plate upside down.

“Yes. And ‘the cats alive are the turning stone.’ Interesting, my brother. Very interesting.” Raistlin placed the plate carefully down on the table, his lips pressed together in thought.

“Wait a minute!” said Earwig. “I just remembered something.”

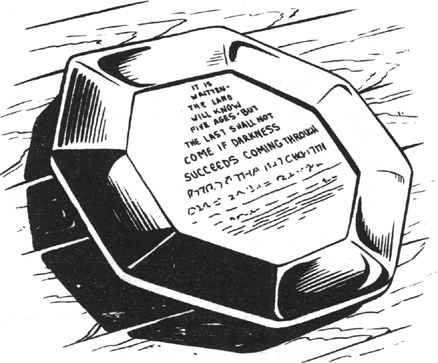

Leaping up, he ran across to another table, grabbed hold of an empty plate, and brought it to the mage. “Look! Another poem! I found it when I’d finished my dinner.”

He plunked the plate down in front of Caramon, and, seeing the fighter absorbed in reading it, appropriated his mug of ale.

It is written,

the Lord of Cats

will come, aiding his

dominion, leading only

for them, following no other

the agents for one and three.

The cats alive are the turning stone,

they decide the fate, darkness or light,

in the city that stands before the first gods.

“ ‘The city that stands before the first gods.’ ” Raistlin repeated, taking the plate from Caramon and reading it again and again. He was always interested in stories and rumors of the first gods, the gods he truly believed still existed. “In all our travels, my brother, we’ve never come across anything like this! Perhaps here I’ll find the answers I seek!”

“Uh, Raist!” Caramon said warningly.

The other patrons had fallen deathly silent and were staring at the brothers and the kender with dark and angry expressions. A few were rising to their feet.

“What do you strangers think you’re doing? Mocking the prophecy?” demanded one, his hand clenched into a fist.

“We’re just reading it, that’s all,” began Caramon, face flushing. “Is that a crime?”

“It could be. And you won’t like the punishment.”

Caramon rose to his feet. He was one against twenty, but the big warrior was undaunted by the odds. He could see, out of the corner of his eye, his brother’s hand glide swiftly to the pouch Raistlin carried at his side—a pouch whose contents were as magical and mysterious as the man who used them.

“A fight?” asked Earwig, jumping up and down. The kender grabbed his hoopak. “Is there going to be a barroom brawl? I’ve never been in a barroom brawl before! Boy, Cousin Tas was right about you guys!”

“There’s no fighting in my establishment,” cried a stern voice. “Come now, Hamish and you, too, Bartoc, settle down.”

The innkeeper placed himself between Caramon and the crowd, making placating gestures with his hands. The men calmed down, resuming their seats and their gloomy conversation. Caramon, slowly and warily, returned to the table.

“I’m sorry, sirs,” Yost said to the twins. “We’re not usually this unfriendly, but there are some bad things happening in Mereklar.”

“What happened to the barroom brawl?” Earwig demanded.

“Shut up.” Caramon grabbed the kender and stuffed him into his seat.

“Bad things—such as the cats disappearing?” asked Raistlin.

Yost stared at the mage in awe. “How did you know, sir?”

Raistlin shrugged.

“But then, you’re a wizard, after all,” continued the innkeeper with a sidelong glance. “I guess you know a lot of things the rest of us don’t.”

“And that’s why everyone’s ready to leap down our throats?” asked Caramon, pointing over his shoulder with his right thumb at the others in the inn.

“It’s just that our cats mean as much to us as his word of honor means to a Knight of Solomnia.”

Thinking back to his friend Sturm, Caramon was impressed. The Knights of Solomnia would willingly die to uphold their honor.

“Sit down, sir—”

“Yost. Everyone just calls me Yost.”

“Sit down … um, Yost,” said Raistlin in his soft voice, “and tell us about the cats.”

Nervously, glancing back again at the other patrons, Yost took a seat opposite Earwig.

Caramon reached for his ale, only to discover that the kender had finished it.

“I’ll have the girl bring you something else to drink,” Yost said.

Caramon looked at his brother, who shook his head, reminding the warrior of the depleted state of their funds. The warrior heaved a sigh, “No, thanks. I’m not thirsty.”

Smiling, the innkeeper gestured at the barmaid. “On the house,” he said. “Maggie, bring us glasses and my own private stock.”

The barmaid returned, bearing a dust-covered brown bottle that Caramon recognized as distilled spirits. Yost poured a glass for himself and one for the warrior. Raistlin declined.

“You want some?” Yost asked the kender. “It’ll curl your hair.”

“It will?” Earwig asked, gazing at the mixture in wonder. The kender ran a hand over his topknot of hair, his pride and joy. “Uh, I guess not, then. I like my hair the way it is.”

Yost continued, “In Mereklar and the area around the city, we believe that our cats will one day save the world.”

Caramon sniffed at the drink he had just been offered and gingerly took a small sip. He grimaced at the taste, then his eyes widened with delight at the pleasant burning sensation warming his insides. He belched and took a larger gulp.

“How?” asked Raistlin, glancing at his brother and frowning.

“Nobody knows for sure, but we all believe it will happen. Our heritage is based on it.” Yost rolled the liquor on his tongue and swallowed. “That’s why cats are always welcome in any home in Mereklar. It’s against the law to harm a cat, punishable by death. Not that anyone would.” The innkeeper gazed around sadly. “I used to have thirty or so here, myself. They’d be walking around, jumping on your shoulder, curling up in your lap. The choicest bits on everyone’s plates were theirs. The sound of their purring was so soothing-like. And now”—he shook his head—“they’re gone.”

“And you’ve no idea where?” Raistlin persisted.

“No, sir. We’ve looked. And there’s not a trace of ’em. Another drink, friend?” Yost held up the bottle. “I can see you enjoy this.”

“I do!” said Caramon, tears in his eyes and a huskiness in his throat. “What’s it called?”

Dwarf spirits. Hard to come by these days, since the dwarfs have closed up Thorbardin.” Yost turned to Raistlin. “You seem unusually interested in our business, wizard. May I ask why?”

“Show him the paper, Caramon.”

“Huh? Oh, yeah.” Fumbling beneath his leather harness, the warrior brought out the parchment they’d found at the crossroads and exhibited it to Yost.

“Ah, yes! The council voted to offer a reward to anyone who could find our cats—”

“It doesn’t say so,” Caramon pointed out.

“No, well.” Yost flushed, embarrassed. “We know that to the world outside, our love for our cats seems kind of strange. We didn’t figure outsiders would understand until they got here.”

“If they got here,” murmured Raistlin, with an unpleasant smile.

Yost glanced at the mage sharply. Not certain if he had heard him correctly or not, he decided to ignore the statement.

“The idea of the reward came from the city’s Councillor, Lady Shavas. If you’re interested in the job, she’s the one you should talk to.”

“We intend to do so,” said Raistlin, glaring at Caramon, who was helping himself to another drink of the potent brew.

Earwig yawned. “Are you going to tell us any more stories? What about this Lord of the Cats? Do you know him?”

“Ah, that.” Yost stared into his drink. He appeared highly uncomfortable. “The Lord of Cats is the king of the cats, the deity who tells them what to do.” Pausing, taking a small swallow, he went on, “The only thing is, though, the stories aren’t clear as to whether he’ll help the world or destroy it.”

“So you believe in the Lord of the Cats?” Caramon asked.

“We believe in his existence,” Yost said, glancing around nervously as if he feared he was being watched. “We just don’t know what motivates him.”

Caramon reached for the bottle. Raistlin’s hand shot out and closed over his brother’s wrist.

“Where’s the gate of which the prophecy speaks?” the mage asked.

“We don’t know much about the prophecy, I’m afraid,” said Yost. “It was found long ago, right after the Cataclysm. Maybe if we did, we’d know what was going on. Still, if you’re interested, I’ve heard that Lady Shavas has books that tell about the Lord of the Cats and the prophecy and some of these other things. They’re written in the your language—the language of magic, though there hasn’t been a mage in these parts for over a hundred years. One was never wanted, if you get my meaning.”

The bartender stood up and prepared to leave, taking his bottle with him, much to Caramon’s disappointment.

“You look done in. Why don’t you go back to your rooms?” suggested Yost pointedly.

“Thank you for your concern,” returned Raistlin. “But we’re not tired.”

“Suit yourself.” Yost shrugged and left.

Earwig was, in fact, fast asleep, his head pillowed on his arms. Caramon, probably as a result of the liquor, was glassy-eyed, staring rapturously at nothing. Reaching across the table, Raistlin grabbed him by the arm and shook him.

“Uh?” said the big man, blinking.

“Sober up, you fool! I need you. I don’t trust that man. Look, he’s talking to someone in the corner. I want—”

Raistlin saw, out of the corner of his eye, the line. A faint, though definitive, illumination was rising from the floor—a stream of white light running the length of the room, flowing north. He felt power, power that was as old as the world, power that ran through Ansalon, over the oceans, and beyond, extending to unobserved, inconceivable realms. Only those who walked on shadowy planes could know of such realms. Or one who had made contact with another who walked there.

Shuddering, Raistlin closed his eyes. When he opened them and looked again, all he saw was the floor—solid, dark with age, wet with spilled ale.

“What is it, Raist?” said Caramon, his voice slightly slurred. “What’s the matter? What’s down there?”

Caramon hadn’t seen it. Raistlin rubbed his eyes. Was it his sickness, playing tricks on him again? Wine on his fingers made his eyes sting and water. He peered through the doorway at the side of the room to the fireplace in the main hall. There was the line again, an eerie white light, about a handspan wide. He turned his head, looked at it directly. The line disappeared.

“Raist, are you all right?”

“It must be a trick of my eyes,” Raistlin muttered to himself, though he knew, since he had felt the power, that it wasn’t.

But with the power came fear—horrible, debilitating fear. He didn’t want to meet him again. He wasn’t ready. The mage studied the ceiling, the beams, supports, and struts made from thick wooden bars that formed an archway overhead. Whenever he looked somewhere else, the line became visible—soft light rising from the floor. Sought directly, it vanished.

Raistlin grabbed his staff and quickly stood up, knocking over a bench.

“Barroom brawl?” Earwig’s head jerked up. He blinked sleepily.

“Hush,” said Caramon.

“What’s Raistlin doing?” whispered the kender.

“I don’t know,” Caramon shot back. “But when he’s like this, you better leave him alone.”

What have I seen? What could it be? Do I even really see it? The mage moved to the south wall of the large eating hall. He looked out the back window and stared up into the sky. The glow appeared on the soft green grass lit silver and red in the light of the two moons. Raistlin kept his eyes open so long that they began to tear. The line grew brighter.

Returning to the table, Raistlin thrust his fingers into his glass of wine and wiped them across his eyes, the alcohol making them water again. The line became clear to his blurred vision—a band of power leading north. Raistlin faced the north window and saw that the stream flowed from the floor, through the wall, and out into the grass—a steady flowing river of white light. The mage sat down heavily on his bench.

“Hey, Raistlin,” Earwig cried, jumping to his feet. “You’re crying!”

“Raist—”

“Shut up, Caramon.”

Sweeping the staff over the kender’s head, causing Earwig to duck or be decapitated, the mage pointed downward.

“What do you see, kender?”

Earwig, startled by the question, followed the length of the staff with his large brown eyes. The pale blue orb at its top hovered inches from the floor.

“Uh, I see wood and a few dust bunnies. Isn’t that a funny-name? Dust bunnies? I guess it’s because they look like little rabbits—”

“Look at me,” ordered the mage.

“Sure.” The kender looked up obediently.

Raistlin put his fingers in his glass and flicked wine straight into Earwig’s wide-open eyes.

“Ouch! Hey, what are you doing?” Earwig cried in pain. He rubbed his hands against his eyes, trying to clear them of the spirits.

“Now what do you see?” Raistlin asked again.

The kender, squinting, tears running down his cheeks, peered around blearily. “Oh, wow! The room’s gone all blurry. Everyone’s sort of swelled up! Thanks, Raistlin. This is fun!”

“I mean on the floor,” said Raistlin, exasperated.

“I can’t see the floor,” the kender said. “It’s nothing but a dark lump.”

Raistlin smiled.

“What is it, Raist?” asked Caramon, tensing, knowing by the expression on his brother’s face that something remarkable had occurred.

“Hey, Caramon, what do you see?” Earwig cried gleefully. Grabbing the glass, the kender tossed wine in the warrior’s face.

“A dead kender!” Caramon shouted, spluttering. “What do you think you’re doing?” he demanded, collaring Earwig.

“Peace, my brother,” Raistlin said, holding up the palm of his right hand. Caramon let go of the kender, pushing him roughly into the seat.

“By the way,” the mage continued mildly, “what do you see, Caramon?”

“Not a damn thing!” the warrior muttered, wiping his streaming eyes with the backs of his hands.

“Nothing on the floor?”

“What’s this about the floor? You keep staring at it, Raist. It’s just a floor, all right?”

“Yes, just a floor. Caramon, go find that bartender. What’s his name … Yost.”

“Sure, Raist.” Caramon’s eyes lit up. “Do you want me to bring him back?”

“No, just ask him a question. Which direction is Mereklar from here?”

“Oh.” Caramon shrugged. “All right.”

“I’ll come with you,” offered Earwig, growing bored now that the stinging and burning had faded from his eyes.

The two left. Raistlin fell limply back into his seat. He felt drained, suddenly completely bereft of energy. The line was magic, visible to his eyes only. But what did it mean? Why was it there? And why this tiny, icy sliver of fear? …

Caramon found Yost and the bottle of dwarven spirits. Earwig watched and listened to them for a while but soon grew restless. He didn’t want to go back into the eating room. He’d been there already.

“I guess I’ll go out for a walk,” he said to Caramon.

“Uh, sure, Earwax. Go ahead.” The big warrior nodded. His voice sounded fuzzy.

“Earwig! Oh, never mind!”

Hoopak in hand, the kender skipped through the inn’s front door and ran smack into three men, standing in the moonlight.

“Excuse me,” said Earwig politely.

The men were tall, muscular, and wore black leather clothing that reeked with age. Wide straps crossed their bodies, holding bags and glittering, bladed weapons.

“Hello, little one. Do you mind if we ask you a question?” the man standing in the middle of the three asked in a smooth, rich voice. The ruddy glow from the firelight illuminated his face, and the kender was fascinated to see that the man’s skin was as black as the night around them.

“No, please do!” Earwig urged.

The man’s blue eyes shone deep red in the firelight. Deftly, with a graceful and fluid movement, he caught hold of one of the kender’s small hands that was sliding into one of the man’s own pouches.

“I’d keep that hand to myself, if I were you,” advised the black-skinned man.

“I’m sorry,” said Earwig, staring at his hand as though it had leaped from his body and was now acting on its own. “I can’t think how it came to be there.”

“No harm done. My friends and I”—the man indicated the two other men standing next to him—“were wondering where you got that magnificent necklace?” He pointed to the silver cat’s skull that hung around the kender’s neck.

“What necklace?” Earwig said, confused. Truth to tell, he’d forgotten all about it. “Oh, this?” He glanced down, saw it, and held the charm out for the men to admire. “It’s an heirloom, been in my family for days.”

“That’s too bad,” said the black-skinned man. His eyes gleamed as red as the ruby eyes in the charm’s skull. “We were hoping that you might remember where you got it, so that we could get one for ourselves.”

“Well, I can’t, but you can have this one,” offered Earwig, who loved giving presents. He tried to unfasten the chain. It wouldn’t give. “That’s odd. Uh, well, I’m sorry, sir. I guess you can’t have it.”

“Yes, we’re sorry, too,” the leader said in a soft voice. He leaned down, nearer Earwig, and the kender saw that the man’s red-glowing eyes were slightly slanted. “Take your time. Think about where you got it. We have all night.”

“Well, I don’t!” Earwig snapped. He was beginning to tire of the conversation. Besides, there was no telling what trouble Caramon was getting himself into without the kender around to keep an eye on him. Earwig moved to push past the three men, but they blocked his way. One of them put a rough hand on the kender’s arm.

“We can drag the information out of you and your guts along with it!”

“Could you really do that?” Earwig asked, thinking things might be getting interesting again. “Drag out my guts? How? Through my mouth? Wouldn’t it be sort of messy—”

The man growled, his grip on Earwig’s arm tightened painfully.

“Wait!” the black-skinned man ordered. “You’re positive, kender, that you can’t think how you came by the necklace?”

Back to the necklace again. Earwig jerked his arm free. Now he was beginning to get irritated.

“No, I can’t! Really! Now, if you’ll excuse me, I must be getting back.”

The kender took a step toward the three men, giving every indication that if they didn’t move, he was going to walk through them. The leader stared down at him. The red eyes flashed. Suddenly, with a fluid and graceful bow, he glided to one side of the door. His henchmen stepped back, out of the kender’s way.

“If you remember how you came by the necklace, please tell us,” whispered the smooth voice as the kender walked past him.

When Earwig turned to reply, he saw, to his amazement, that the men were gone.

Sitting alone, Raistlin was seized with a coughing fit. His breath refused to enter his lungs. He felt himself begin to lose consciousness. His head swayed slightly and he looked down into his cup, where he saw the remainder of his medicine, the leaves sticking to the bottom. Reaching out with a skeletal hand, he clutched at the passing barmaid.

“Hot water!” he gasped.

Maggie stared at the hand clasping her apron, the hand colored gold and as thin as death.

“Are you ill, sir? Can I help?”

“Water!” Raistlin snarled.

The woman, half-afraid, rushed to fill the order.

Raistlin slumped over, his head buried in his arms. Motes of light danced before his eyes, as he had seen at an illusionist’s show once—dancing, spinning, sparkling, changing color, shape, form, but always illusory, always unreal, no matter how strongly he willed it to be different. He thought of how often he wanted things to be different, to change because he desired them to change. He thought of how many times he’d been disappointed.

Why couldn’t he have been given the physical strength to match his mental strength? Why couldn’t he be handsome and winning and make people love him? Why had he been forced to sacrifice so much for so little?

“So little now,” Raistlin said to himself. “But I will gain more as time goes by. Par-Salian promised that my strength would someday shape the world!”

He fumbled at his side for the bag of herbs. Who knew but what this might cure him? He had thought he was feeling stronger. But his weak hand would not obey his command, and it occurred to Raistlin that he required Caramon’s help.

I don’t need him, the mage thought with dull defiance. The lights in the room dimmed with the darkness covering his eyesight. Listening to himself, he realized how childish he sounded. His lips twisted in a bitter smile. Very well, I need him now. But there will come a time when I won’t!

The barmaid brought him his water, setting the pitcher down quickly, wanting to leave, wanting to stay. Maggie didn’t like the mage with the gold skin and wizard’s staff and the terrifying eyes that stripped away the soul. She didn’t like him, yet she was fascinated by him. He was so frail, so weak, yet—somehow—so strong.

“I’ll pour the water for you, sir, shall I?” she asked in almost a whisper.

Gasping, almost unable to lift his head, Raistlin nodded and clutched the cup with both hands. He drank deeply, his tongue numbed, the lack of sensation caused by his faintness removing any discomfort from the heat. He emptied the cup and let out a long, steady breath. The mage leaned against the back wall of the tavern, his eyes closed to the world.

Caramon found him thus when he returned. The warrior slid quietly into the booth, thinking his brother asleep.

“Caramon?” Raistlin asked without opening his eyes.

“Yeah, it’s me. You want to go upstairs now?” The warrior’s words were slurred, and his breath reeked of the foul-smelling liquor.

“In a moment. Which way is Mereklar from here?”

“North. Almost due north.”

North. Without opening his eyes, Raistlin could see the white line running north, leading him, guiding him.

Impaling him.