Roger Federer. [Art Seitz]

The best game philosophy is to keep the ball in play, even when playing a standard match at club level. Don’t hit toward your opponent but slightly away from him to make him work at it, then hit to the open court when you have a sure shot. If you keep the ball in play without making silly errors, you’ll slowly learn to win points. It may surprise you how many people—perhaps 90 percent of the 50 million or so who play tennis around the world—cannot hit twenty balls firmly back and forth in the court.

In club play, more points are lost on mistakes or unforced errors than are won by hitting winners. If you keep the ball in play, you’ll end up winning more points than you’ll lose. Rallying is the part to learn first.

In a match on any medium-to-slow court, professionals rally before trying to hit winners. You should do the same. Hit your ball 3 to 4 feet over the net with power and plenty of topspin, not only to be safe, but also for depth and higher bounce. This will force your opponent to return from farther back, reducing his chances of hitting a winner or an angled placement that can catch you unprepared.

If your opponent has a weak backhand, or his forehand is a much bigger weapon than his backhand, direct your shots to his backhand side. If your opponent’s game is balanced, hit most of your shots crosscourt or down the middle, over the lower part of the net. Avoid making errors or opening up your court. When you start sensing where your opponent is vulnerable, hit the ball there, always keeping a good margin for error. For example, if you know that in practice you need to aim 3 feet inside the sideline to avoid hitting out in a down-the-line shot, do the same in a match. The same goes for height over the net: if aiming 1 foot over the net results in too many hits into the net during practice, then during a match hit the ball at least 2 feet over the net, using plenty of topspin.

If the ball is bouncing too short in your opponent’s court, hit it higher. You’ll achieve more depth and more jump on your shot. It is far less dangerous to hit the ball closer to the service line than to go for the baseline. And it doesn’t make sense to hit the ball long when you have enough topspin to make it land well inside the court and make it jump.

After you hit a forceful shot, move a few steps into your court. Your opponent will likely respond with a shorter or easier shot. As you move forward for a shorter ball, hit your ground strokes lower and with more topspin by closing the racquet face and pulling up more on the stroke, making sure to clear the net. An upward effort and more topspin are needed because the ball has a shorter trajectory to be lifted over the net and then go down into your opponent’s court. The same goes for passing shots. They need to be hit with plenty of topspin so the ball will dip down soon after crossing the net, making it more difficult for your opponent to volley.

When you hit a good crosscourt shot from the backcourt and your opponent is also back, drift slowly toward the middle. It is very likely that your opponent will hit crosscourt, the best percentage shot for him. Don’t run toward the center of the court, or you will create an opening for your opponent to hit to the place you just left. If your opponent shoots down the line, close to the sideline, as you drift to the center, he’ll be risking much more. But you’ll be facing slightly in that direction as you drift toward the middle, so you’ll just need to pivot and accelerate to reach the ball. If your opponent hits behind you, pivot back and you should be close to the path of the ball.

When you are pulled wide, which occurs mostly when receiving a cross-court shot, hit the ball back crosscourt, so that you don’t open the court much to your opponent. A weak shot, of course, is a setup for him. It will be short and allow him to attack you on either side, to come to the net, etc. But if you hit the ball hard and with plenty of topspin, he won’t be able to do something surprising with it.

If you don’t have a strong crosscourt shot but are pulled wide, lift the ball high, down the middle, and past your opponent’s service line. This tactic will give you plenty of time to return to the middle of your court, ready for his next shot.

At a high level of play, a crosscourt shot takes precedence over any other shot as a return of a good crosscourt shot. The exception would be your opponent has stayed too close to the side he made the shot from, leaving the other side wide open for your down-the-line shot. Top pros engage in crosscourt rallies mixed with down-the-middle shots, risking nothing, waiting for a weaker shot that opens the play for something different.

To show you how dangerous down-the-line shots can be when you are pulled wide, imagine yourself playing someone good. You hit only down the line, while the other player hits only good crosscourt shots. In a short time, you are out of breath because you are running many more yards to get to each shot than your opponent. A good crosscourt shot pulls you beyond your sideline so that your down-the-line shot can’t be parallel to the sideline, or else it lands outside your opponent’s court. You have to angle your shot toward his court. After the bounce, the ball will continue to approach the middle, giving him a good chance to cross it the other way, where you left a wide-open court. This forces you to race all the way across your court. A few shots like that, and you feel like you are chasing a rabbit, while your opponent strolls around the court. You may also start to hit short, allowing your opponent to come to the net.

You need to adjust your game tactics to your opponent’s play. Stay cool and see what gives him trouble, what he likes, and what throws him off. Unless you know your opponent well, “feel” him or her at the beginning of a match. Mix in some junk shots with your good shots. Many players don’t handle a change of pace well. Others thrive on your hard shots, making you feel that the better you are playing, the better they play. Throw some high topspin shots that bounce deep and high and see how your opponent reacts. If he has trouble, keep it up. It’s part of the game. If you are playing competitively, you are not there to hand the match to your opponent, but to beat him, or at least to have him sweat it out until the last point is over.

Practice matches or social matches are different. You try to get the best workout possible. Sometimes your friend across the net doesn’t have a good backhand. If you hit mostly to your friend’s forehand, you’ll get the best possible practice, only reverting to winning tactics if you need to. When practicing, focus on consistency and accuracy, rather than raw power. You can hit hard but use a lot of topspin. The tendency in tournament matches is to hit forward, flattening out the stroke. Practice the other way around. Accustom your muscles to lifting the ball. It will be easier to resort to topspin in tight spots in tournament play.

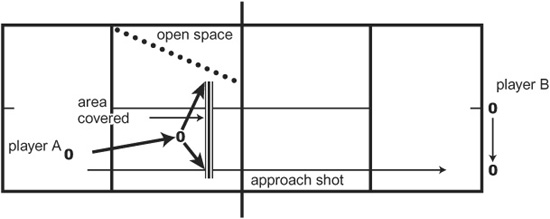

When you approach the net, whether with your forehand or backhand, a down-the-line approach will cut the angle of your opponent’s passing shot. In other words, after you hit the ball, continue to advance, keeping to the side from which you made the approach—perhaps 2 to 3 feet from the centerline depending on your shot’s depth and how close you advance to the net. Your opponent will have only a small opening to pass you with a sharp and short crosscourt. See illustration below.

For the average player such a sharp angle is a low percentage shot. Unless he has plenty of topspin, he’ll have to resort to hitting a slow shot to place the ball in the open space, giving you a chance to run it down.

If you are in your backcourt, and your opponent has made a good approach that doesn’t give you much angle to pass him, you can dink the ball—hit it so low and slow or with so much topspin that the ball goes down to his feet or to his side. From there, your opponent will have trouble volleying with pace, which will usually give you a shorter ball and a better chance to pass him with your next shot. If your opponent is very close to the net, your best choice is a good lob, making sure you send the ball well over him even if he jumps back and up. As a dink usually drives your opponent close to the net, the lob is a good follow-up shot.

Let’s say you are a right-hander playing a right-hander. A very good tactic for you is to stay in the backcourt, a little to the left of the center. Pound the ball into your opponent’s backhand, again and again, using a backhand crosscourt and forehand inside out—where a forehand is angled to the right, as opposed to the more normal crosscourt shot to the left.

Net player’s coverage.

Whenever possible, run around your backhand (i.e., run beyond the ball’s path to hit a forehand instead of a backhand), hitting inside-out forehands across to the right. Your opponent will keep trying to force you to hit the weaker backhand shots, and to do so, he will have to send the ball closer to your left sideline and possibly out of play. After every strong shot, especially with your forehand, move a yard inside your court, staying still slightly to the left of the center, ready for a weaker return. After a while, your opponent will feel pressured. There’s not much room for a crosscourt backhand, and he’ll risk sending the ball down the line. If he makes a good shot, run it down and hit it with plenty of top-spin, high and safely, toward the middle of his backhand side. Then move into the court again, toward the left, and keep pounding his backhand side. As soon as he makes a weaker shot, jump on it crosscourt with your forehand, sharply angled and with plenty of topspin. It should be a safe shot if you produce enough topspin, and your opponent will have a hard time reaching it and even more difficulty handling it. If by then you are at the net, you probably have a big open court for your volley and an easy put-away or smash.

This strategy requires a lot of patience and very good stamina. Some pros with a big forehand sometimes park themselves 2 to 3 feet to the left of the center of the court, pounding their forehands patiently to their opponent’s backhand side or hitting sharp crosscourt shots when the ball comes to their backhand. They wait for the short ball they can attack savagely, hitting far from their opponent’s reach. When they reach the net, the point is almost won. Unless their opponent, risking everything, hits a miraculous winner or an incredible angle shot, fate is in the hands of the attacking player.

Hitting your first serve in is a very good way to put more pressure on your opponent. Even a slower first serve is treated with more respect than a second serve of the same speed. If you miss your first serve consistently, the other player will soon be attacking your second serve and making better returns. You can do the same if your opponent misses his first serve. Move inside the court and attack his second serve.

The safest return of serve is usually crosscourt, over the lowest part of the net and toward the longest extension of the court. When an opponent is coming to the net following his serve, pounding the ball cross-court will give good results: the ball will dip down sooner than a down-the-line shot, and its speed will make it difficult for your opponent to return. It may even pass him by. This tactic reduces your risk compared with hitting a down-the-line return of serve, closer to the sideline and over the higher part of the net.

Many players have had the opportunity to play on more than one surface, such as Har-Tru or Fast Dry courts (green clay), red clay, hard courts, or carpet. Changing from one type of surface to another requires making adjustments both on timing the ball and in your swing. Hard courts can also vary in speed according to their composition. Adding more fine sand to the paint mix, for example, makes the surface slower because it creates more friction on the bounce. There are differences even among the same type of clay courts, depending on how damp the court is. Grass courts play faster when they are damp. Indoor carpets at different clubs can differ in texture, too. Some players have difficulty adjusting to different court surfaces. Your main focus should be on stalking the ball after the bounce, so you can adjust your timing to the flight. As satisfying as it is to hit the ball hard and fast, it is far better to lose some ball speed in the first few minutes of your adjustment than miss and lose confidence. Of course, you’ll have more time on clay, especially red clay. The tendency, therefore, when changing from clay to hard courts is to rush. But, as you know, if you rush on any surface you’ll be in trouble, especially on hard courts. Take your racquet back early, and you’ll be caught with your racquet behind, or you’ll have to force it forward too fast, losing control.

To counteract the tendency to rush, shorten your preparation on hard courts. Keep the racquet in front longer, closer to the ball than usual, and then swing. Make sure you accelerate with the ball already on your strings. Rather than following the ball with your racquet, swing up and across the body to brush it more and increase control.

Overall, let your body tell you how it wants to move on the surface you are playing. Forcing your footwork unnaturally is a primary cause of leg, hip, and lower back injuries in tennis.

Be a natural. In this sense, copy the pros.

THE ZONE—CALMNESS AND TRANQUILLITY

How do top pros achieve such a state of confidence and achievement? Where a normal human being would succumb under the pressure, top pros usually look serene. Eight thousand people in the stands cheering or cursing them, and they’re still able to perform. Not only in tennis, but in other sports as well, many top performers exemplify a state of calm tranquillity that may seem difficult to achieve.

Let’s define nervousness. It is usually the feeling resulting from considering too many things or possibilities within a short period of time. Would you be nervous if you knew your exact course of action? Probably not.

Another cause of nervousness is looking around too much, causing you to receive too many pieces of information. This again impedes focusing on one thing: your contact with the ball.

To solve nervousness or lack of focus, some of the top tennis players perform exercises prior to a match. Billie Jean King, for instance, would sit at a table staring at a ball for a good period of time until she no longer felt compelled to look somewhere else.

A useful habit between points is to look at something far away, keeping your eyes there at least for a few seconds. You’ll feel calmer, more space, and more in control of things around you.

Overall, think as little as possible, and stay in present time. Don’t rush. Keep your attention on the ball, try to see its seams, and focus—first on feeling the contact point and then on the full finish of the stroke. Always be aware of the feel of the ball on the strings, ideally as a brushing action, no matter how short, rather than a straight hit. Focusing on this calms your mind. Also, if you feel the contact, you’re more likely to remember that particular feel during the game and be able to repeat it consistently.

Of course, you would vary all these tactics depending on the degree of success your opponent has in handling them. You can surprise your opponent with a change here and there, but keep winning tactics steady. Don’t change a winning game—but always change a losing one. Don’t vary winning tactics just for the sake of change. It might give your opponent a lift and change the whole match.

The same goes for your basic game. You know your best weapons. If you have the fundamentals of this book down well, your consistency will be very high. Stick to your topspin and the finish of your ground strokes. They will keep the ball in the court, and you won’t have to resort to hybrid strokes.

Stay in the match as long as possible. Don’t rush. Keep the ball in play one time more than your opponent, and you’ll beat players that look much flashier than you.

Overall, respect your opponents and their shots. Never underestimate anyone. If you can beat some opponents easily, do so without snubbing them. They will appreciate your game and your behavior. They will also know that the points or games they won were won on their own, and you didn’t hand them anything they didn’t earn.

And if one player keeps beating you no matter how well you play or how hard you try, recognize that he or she is better than you are at this point in time. Keep playing your best and learn from the experience. It is possible to improve every day, to learn something good every day. And we learn something every day, whether we recognize it or not. A positive experience depends only on you.