CLERMONT FOOT 63

Innovate through diversity

The reluctant, sexist, innovator / Diversity drives innovation / Women need champions, not mentors / Menstruation matters

The man who just walked into a downtrodden Paris café in Boulogne-Billancourt does not look like a pioneer. He does not even claim to be a pioneer. You could show his picture, or mention his name, to most football fans in France, and they would not know who he was. That’s how he likes it. But Claude Michy, an understated events manager with a love of motorsport, is unique in modern-day football. He is the sole owner of his local football club, Clermont Foot 63, who play in France’s second division, Ligue 2. And in summer 2014, he found a brilliant way to get an edge. He appointed a female coach to lead the team.

The night before I meet Michy, Corinne Diacre has just coached her hundredth game in charge of Clermont. It was a 1–1 draw against Brest. That she is still there nearly three years on is to Michy’s great credit; not because he might have sacked her, but the opposite. In September 2016, the French football federation asked Diacre to coach the France national women’s side. She said no, out of loyalty to Michy – she felt she owed him that.

Over the next few hours, Michy will tell me how Diacre brings an edge to Clermont. Their story is not about female empowerment, or bringing a more empathetic management style to the club. It’s about creativity; how Michy, best described as a reluctant innovator, wanted a female coach for his team, and found the right one (eventually). He has gone against the grain of football orthodoxy. He has taken a risk. His innovation is not granting creative freedom, but granting creative freedom to a woman in an industry where hardly anyone else has dared do the same.1 And it has worked.

Studies on women in business suggest that a female team coach would be successful. Professor Kathleen O’Connor, an organisational psychologist who studies negotiation and teamwork at Cornell University, tells me that women demonstrate different behaviours to men in a negotiation process; that women will fight very hard on behalf of a group, but are less effective when it comes to representing themselves. And that women in general use more collaborative skills with teams. The ‘command and control’ form of management is outdated, she says, only required in crisis situations and tends to be used by those, usually men, who feel threatened.

There was some symmetry to the timing of my visit. Clermont faced the same opponent, Brest, the previous night as in Diacre’s first game in charge. Before that match, Brest coach Alex Dupont presented her with a bouquet of flowers.2 She kissed him and smiled politely. Brest won 2–1.

Last night, there was no bouquet for Diacre. That seemed significant to me, as I will explain later. Brest was top of the table. Clermont, in fifteenth place, frustrated them. It was a freezing night and the stadium was not even half-full – just over two thousand hardy souls turned up. But Diacre has been successful. Clermont has the seventeenth lowest budget in the division, and finished twelfth (2015), sixth (2016) and twelfth again (2017). Diacre over-achieved with the squad she had. The risk paid off.

‘It was no risk for me,’ says Michy. ‘At least, it’s exactly the same risk as if I’ve hired a man. I chose someone based on their competence. Okay, she’s a woman too. But I’ve not chosen a woman. I chose someone who played 120 times for their country [Diacre was a centre-back for France’s women’s team] and spent five years as assistant coach to that team. So there’s no great risk there. I don’t see myself as doing a great service for diversity for bringing in a female coach. It surprises me when I hear that. There are women who are team managers in Formula 1. There are female prime ministers in Germany and the UK. So when people question the appointment of Corinne as a woman in the men’s game, it’s a little bit reductive, don’t you think?’

Michy is being disingenuous here. Diacre was only appointed after his first-choice as coach, Helena Costa, walked out a few days after her appointment and before she had even taken one training session. Neither coach was his idea; both came from agent Sonia Souid, who first convinced Michy that Costa, a Portuguese who had been in charge of the Iran women’s team, would be a good replacement for Régis Brouard.

Michy tells me that Costa walked out because her mother was ill in Portugal, and it was only once she arrived in Clermont that she realised things would be difficult. Costa tells another version: that players had been signed and pre-season matches arranged without her knowledge. Sports director Olivier Chavanon had signed players she didn’t want, refused to reply to her requests for information, and when he did reply said he was ‘fed up with her emails’.

Before Costa’s departure was publicly announced, Michy spoke to the players in the changing-room. ‘I said, “I want to know, all of you in here, who has never been dumped by a woman? Lift your hand if that’s the case.” And no one lifted his hand … “So now we are all on the same team, because Helena Costa is leaving.”’

To me, this reeks of everyday sexism. Michy, to his credit, does not disagree. ‘I think I have a sexist side, it’s a tendency for people of my generation.’ He is 67, and his reported comments after Costa’s departure certainly support that case. He said: ‘She’s a woman so it could be down to any number of things …’

Michy, then, is a self-confessed sexist appointing women to senior jobs. His main business, which is to organise motor-shows, Grands Prix, ice figure-skating and boxing, also has senior women in charge. Is this admirable, or worrying? He is filling the positions with women, but not changing (his own) attitudes – even though he tells me that women are smarter than men.

It feels like a misnomer to describe gender balance in the workplace as a diversity issue. After all, 60 per cent of graduates entering the workplace are now female, and women make 80 per cent of consumer decisions. ‘The question should not be why, but why not?’ asks Aviva Wittenberg-Cox, a gender balance expert who sits on a committee focused on redressing the balance in French football.

Wittenberg-Cox makes a compelling case for women in football: she says that companies that are more gender-balanced in leadership outperform their peers; and those who are better at promoting women are happier places to work. She identifies three barriers for most organisations: that the leaders are not aware or skilled at leading the change; that the culture unconsciously excludes female talent; and that the systems underwrite those behaviours with unconscious bias impacted into the existing talent management system. ‘We’ll only really have equality when lousy women get promoted as much as lousy men,’ she jokes. We’re a long way from that at the moment. She sees her role as changing the dialogue around gender balance: it’s not about human resources, unconscious bias, or even a strategic goal. It’s simply a cool business opportunity with a clear economic case in its favour.

HOW TO GET AN EDGE – by AVIVA WITTENBERG-COX

Michy seems to have grasped this fact. I like that he could have chosen a man after the Costa experience, but he didn’t. ‘When you want to try something, you have to go through with your ideas, that’s what I think.’ So without telling me, it’s clear he did want to have a female coach in charge. It was not just a PR stunt, especially as Michy himself prefers to stay under the radar. He talks of other French club presidents who are constantly in the media. He is not.

Instead, he felt that his (original) decision to be innovative, to be different and, yes, to be creative could give Clermont an edge. So he approached Diacre, the first woman in France to receive her coaching diploma, after getting her number from the former France women’s coach, Bruno Bini, whose assistant she had been. In fact Bini wanted the job himself. Michy offered Diacre the same salary as the previous coach. She said yes.

‘I said yes because I could not be sure the opportunity would come again,’ Diacre said in an interview with FIFA’s official magazine FIFA Weekly. ‘I had sent my CV to lots of teams in women’s football and had not received any responses. I asked myself: “Should I go there?” The fact it was the men’s game made little difference. I took some advice and everybody said, “Go, go, go!” I just didn’t know if the opportunity would come again. I couldn’t say no. I knew that by saying yes, I would be seen as the woman in a man’s world, but it became the only thing people said to me. From my point of view, Clermont Foot needed a coach, and signed me to be coach. The media talked about me more as a woman than a coach.’

Michy went back to the dressing-room and asked the players another question. ‘You all told me you have been dumped by a woman. Which of you has never found a new woman after that?’ No one lifted a finger. ‘Same here,’ he said. ‘I have found a new woman and her name is Corinne Diacre.’3

Diacre was surprised at just how non-stop the narrative became. ‘Every question I was asked was about being a woman more than being a coach. It was the only thing people had to say to me.’ At a press conference a few months after her appointment, she was so fed up with the constant questions about her gender that she snapped: ‘The first! The first! The first! Can we please talk about football now?’

She was particularly wound up by the question about when and whether she would go into the changing-room. She had never heard Bini, or any other male coach of a female team, asked the same question. She felt certain people wanted her to fail, so they could say, ‘I told you so.’ She said in a rare interview: ‘One thing seems certain: the global narrative is that if I fail, it will be because I’m a woman. I am not the only person around who has had critics, but I think I have had to be brave in the face of many factors.’4

Diacre always had a natural authority. When she played for France, she was the most vocal of her team-mates. ‘You need that personality in the men’s game,’ she said. ‘You could not cope without authority. My management style always involves the players, but being a leader is natural for me, it’s in my DNA.’

There were issues inside the club. One player, one of the most talented in the squad, was unhappy at having a female coach, so he was sold. There was also a power battle over new signings with Chavanon, who left the club the following summer. ‘Some members of my staff put roadblocks in the way,’ she later said. ‘Some of them didn’t want to work with me. As a club we had to decide which way we were going to go and the president backed me. [Football] is a hostile environment. When I arrived I was judged before people knew me, purely because I was a woman. That surprised me. Why make such hasty judgements, be so suspicious?’ Diacre has since taken control of all signings and has proved very canny in the transfer market.5

Michy explains that whenever Clermont lost in that first season under Diacre, the story was: ‘Diacre lost … Diacre loses again … another defeat for Diacre.’ When the team started winning: ‘Victory for Clermont Foot … Clermont win again.’ It was tiresome for both coach and owner. Michy never put Diacre under pressure, or made her fear for her job.

‘I am not a football man but I know we cannot win every game,’ Michy continues. ‘You, me, we are not at 100 per cent every day. We ask professional players to be at 100 per cent all the time. But they are human beings, and sometimes they have ups and sometimes they have downs. Most of the time, when there are downs, the coach is sacked. But that’s not how I do things.’

He is more of a hands-off leader, then. ‘At Clermont, the coach is the boss. I have no expertise in football. So if the coach says, “I want a new player, I’m not happy with this one,” I would say, “That’s fine, let’s do it.” I trust them. My job is to make the coach understand that you have no doubts about them, that you support them totally. Everyone has their own job, their own skills. Mine is to hold the purse-strings.’

This makes him different from other owners in France, many of whom have been super-successful in business. He tells me about Jean-Pierre Caillot (Reims), Jean-Michel Aulas (Lyon), Michel Seydoux (Lille), Louis Nicollin (Montpellier) and Jean-Raymond Legrand (formerly of Valenciennes). ‘They have all succeeded in their own business, but in their football club, it is the opposite. They made profits in business but not in football. It is very strange.’

I ask why no other clubs have followed Michy’s model and hired a female coach. He doesn’t know, but accepts that there might not be many female candidates who have the requisite coaching qualifications. Michy is also sole owner of the club, and his board consists of himself, his son Philibert and a friend. So there are fewer barriers to a decision like this. ‘I can imagine at another club, the discussions might be long.’

Cindy Gallop is not so generous. A former chair at advertising company Bartle Bogle Hegarty, she is now an equality campaigner who set up a website called MakeLoveNotPorn to quash the myths of hardcore pornography and begin a dialogue around how real people have sex. She is pushing for more diversity in the workplace. And she has a sharp tongue quite in contrast with her cut-glass English accent.

‘At the top of every industry there is a closed loop of white guys, talking to white guys, about other white guys,’ she tells me from her apartment in New York. ‘Fuck that shit! Seriously: fuck it! The problem is, we see no change, because the white men at the top, sitting pretty, have absolutely no desire to change. That closed loop is actively closing ranks and keeping them out. It’s not unconscious bias but conscious bias.’

She tells me about a cartoon in web-comic XKCD that has stayed with her. There are two images, one of a man doing maths sums on a blackboard and getting them wrong; the other is a woman doing the same. ‘Wow, you suck at maths!’ is the caption under the male image. Under the female image: ‘Wow, women suck at maths!’

‘Men are hired and promoted on potential and women on proof,’ Gallop continues. ‘And then they are held to a different set of standards. Has she done the job before? Did she do it well enough, or for long enough? I am sick to death of talking about this because I find myself having to say the same thing over and over again. Fuck talking about it, fucking do it.’

Gallop’s language seems a conscious effort to reclaim the ‘swearing space’ usually acceptable for men but not for women. The words are shocking not because they come from a 50-something executive in a smart suit, but because that executive is a female. She forces us to confront our own biases. Are you shocked by the language, and if so, why? Would you be more or less shocked if a man had said the same thing?

I tell her that Michy has fucking done it. Football’s diversity issue is there for all to see. In France, in the 2016–17 season, there were two black coaches in the top division, and in the second division, more women (one) than black coaches (zero).6 In England in the 2016–17 season, there were three black coaches across all 92 league clubs.7

There is a similar issue among coaching appointments in the USA. There have been two black coaches in the 21-year history of the MLS, while the number of black and Latino coaches at the start of the 2017 season, five out of 22 teams, is only one more than in 1998 and 2008; this despite an initiative in 2007 requiring teams to interview candidates from diverse backgrounds. Fernando Clavijo was born in Uruguay, played for the USA national team, and coached New England Revolution and Colorado Rapids in the 2000s. He is now FC Dallas technical director.8 He sounded like Diacre when talking about his opportunities: ‘I always thought that for me to get a job I knew I needed to be better than, not equal to, anybody else.’

‘I refuse to believe that the best people and best professionals are mostly white males,’ added Chicago Fire general manager Nelson Rodriguez. ‘I would find that an incredible set of coincidences.’ Hugo Perez, a former USA youth national team coach, worries that this lack of diversity will leave the nation behind the rest of the world. You need those types of coaches to bring something different in order for us and for our players to be able to compete with the rest of the world,’ he told the Guardian. ‘If you don’t, you’re going to be the same thing you’ve been for the last 20, 25 years.’

Lillian Thuram, a former France defender who now runs an anti-racism organisation called the Lillian Thuram Foundation, believes unconscious bias stops black players trying to become a manager. ‘Sometimes black players ask themselves, “Should I become a manager?” But then they think, even if I get my qualifications, who’s going to hire me?’ he said. ‘I think that, in the collective unconscious, we have trouble imagining a black manager … A black man in charge of the team? That is something people have much more trouble conceptualising.’ He urges black players to continue to get their qualifications, and those making the decisions to question their own biases.

‘Football is missing out on a huge opportunity to galvanise, to energise, and to reinvent the future of the sport,’ Gallop says. ‘Diversity drives innovation. Female coaches bring completely different perspectives and insights to the table. Football leaders are missing out on this totally when they do not embrace a gender-equal scenario.’ Gallop told a Sydney conference in 2016, ‘Women make shit happen, women get shit done. Want to do less work and make more money? That’s the answer … working with women and “people of colour” is uncomfortable because we are “other”. But out of that will come extraordinary insights and perspectives.’

HOW TO GET AN EDGE – by CINDY GALLOP

This diversity is also lacking in women’s football. Only seven of the 24 national teams to compete at the 2015 Women’s World Cup had female coaches. Yet teams coached by women often do better: women were in charge of three of the last four women’s World Cup-winning teams, including Jill Ellis’s USA side in 2015.9

It’s a similar story in the women’s domestic game. In the top two divisions of the FA Women’s Super League, there are five female coaches out of 20 teams. The 2015 league and FA Cup winners, Chelsea Ladies, were coached by Emma Hayes, who might just be best-placed to replicate Diacre’s achievement in the British game. Not that she expects it to happen anytime soon.

‘For me, it’s absolutely ludicrous to think that Premier League teams, who hire expensive management and backroom staff teams to manage the psychology of the dressing-room, have no women in senior coaching positions,’ Hayes tells me. ‘Having gender balance in the dressing-room could have a significant impact on performance. Balance is critical in all areas of our life. But it’s almost like [football clubs] negate the importance of women in their lives. I’m astonished that to this day there are still so few females working in the men’s game.’ She cites the rise in mental health awareness after former England winger Aaron Lennon was detained under the Mental Health Act amid concerns for his welfare in May 2017. Ryan Giggs and Jamie Carragher wrote in their respective newspaper columns that they had seen psychologists during their playing days. ‘There is too much pressure for men, and for me this is another reason why women in a male dressing-room is crucial,’ she says.

Hayes was assistant coach at Arsenal Ladies when the Gunners won the quadruple of Premier League, FA Cup, League Cup, and UEFA Cup in 2007. She then worked in USA, coaching at Chicago Red Stars and Washington Freedom, before returning to Chelsea in 2012. Since then, the team has never finished outside the top two.

So would she be prepared to work as a coach in the men’s game? ‘Of course I’m open to it because, for me, coaching is coaching. I wouldn’t have any issue with that. But I don’t see this issue as something changing quickly, even if it is beneficial to have different people around. If I was in charge of a football club, or a business, it’s something that I would drive.’

Hayes is an eloquent speaker on the subject, even if she gets frustrated (her word, polite for bored) at being described as a role model for women’s coaches. ‘Everyone tells me that’s what I am, but I’m a professional coach first and foremost. We don’t mention it enough: female coaches are always role models, but what are male coaches? This is the language around our game, as though it’s inferior, even though we are more engaged with our fan-base.’

She looks for the same qualities in her players as some of the teams, like Athletic Club de Bilbao and RB Leizpig, that we have already met: how they deal with setbacks, what their idea of success is, what their motivators are, how receptive they are to learning. Like Thomas Tuchel and Didier Deschamps, she is a relentless self-improver. She says it’s harder for coaches to get the same level of feedback as her players. ‘I want more open paths to feedback, as I have to make sure that my performance is improving too.’

Hayes agrees with Gallop’s theory that women have mentors and men have champions, far more prepared to stick out their necks in the boardroom when it matters. ‘No one else is championing these women, so you need to,’ urges Gallop. ‘Strike mentor from your vocab, inherent in the term is a touchy-feeliness. Fuck the mentor and find the champion! Then go out on a limb for them. Women don’t have champions and they need them.’ Hayes believes women are more likely to champion a male coach simply because they are used to one. She is quick to champion other impressive female coaches, the likes of Emma Coates (Doncaster Belles), Gemma Grainger (FA Under-15s coach) and Kelly Chambers (Reading Ladies).

When I speak to Hayes, who was awarded an MBE for services to women’s football in 2016, she has recently returned from an off-season in Japan. While there she lectured coaches (95 per cent of whom are male) on the challenges of the menstrual cycle in the women’s game. She is putting the finishing touches to a paper on the subject – she has been researching it for over two years – and she is scheduled to deliver talks on best practice around the world in 2018.

‘The majority of women, let alone men, are completely uneducated about periods, what they are and what they do. So it’s hard to optimise your performance when you have an unspoken subject that could be affecting you physiologically or psychologically in one out of every four weeks.’

Hayes says that periods can affect reaction time, neuromuscular co-ordination, manual dexterity, blood-sugar levels, aerobic capacity and muscle maintenance in differing ways. Coexist, a community arts organisation based in Bristol, has created an official ‘period policy’ to allow women to take time off, in the hope that the workplace will become more efficient and creative. Women tend to be more creative, for example, in the spring phase of their cycle, days 6 to 12, which is just after their period. This is due to a rise in the hormone oestrogen to help the body prepare for ovulation.

‘This subject is pushed away like a taboo but it’s important,’ Hayes continues.10 ‘I can help achieve best performance and avoid risk and help women live and prosper with something that can be very painful and hard to do. People will think I’m crazy but when they talk about specialists, like coaches for forwards, or nutrition coaches … if I had unlimited resources, I would hire someone to manage my players’ menstrual cycles. This is a value-added benefit that is clearly applicable outside of sports too. It all depends on how creative you want to be.’

Understanding the menstrual cycle is not ‘touchy-feely’, as Gallop might say. It relates back to Geir Jordet’s visual frequency searches: the more information you have coming in, the better the decisions that you can make. Hayes is learning about physiology and psychology because she wants to win. This is her way of getting an edge.

HOW TO GET AN EDGE – by EMMA HAYES

Michy, the Clermont president, might not be ready for a menstrual-cycle coach just yet. But he reminds me that at Clermont, with its low budget, he needs to be smarter than those with a lot of money to spend. So he finds creative solutions. Football remains a mostly conservative world. Who makes brave decisions? When companies are under pressure, the notion of threat rigidity tends to surface: hierarchy, and a focus on the one thing that company does well, takes over. Sometimes this can work, as in the example of Total, the French energy company, who had hoped to get into gas production in America, but ended up grateful it missed out. Another French firm, Kering, sold off brands like Printemps, Fnac and Conforama, and now focuses on more lucrative luxury goods.11

So is it cowardly or lazy not to look at more female options in football? ‘I think most people adopt the cautious approach we like in France, which to my mind is an intellectual madness,’ says Michy. ‘I’m not a pioneer. Hiring a woman as a coach has not changed my daily life. The sun still rises in the east. I don’t feel like I’m an innovator, just because I hired someone with the competence and the skills to do a job. That’s not innovation. Results on the pitch are nothing to do with me. I leave that to the coach and I trust her. When you have the right coach with the right qualities, they can improve the players and make them grow. That coach could be a man or a woman.’

Diacre says that she is not thinking past her daily work at Clermont. And there’s a reason for that. She knows that her only chance of coaching in Ligue 1 will be if she goes up with Clermont. She has done better than expected there, and has been accepted by players, fellow coaches and the media – France Football magazine voted her Ligue 2 coach of the year in 2015. But as Gallop suggested, there is no Michy equivalent in Ligue 1. No one else would give her the trust, patience, time and space to succeed. No one else would champion her, or have the creativity and innovative instinct to appoint her.

Her next job probably will be with the France women’s team. But it would be nice if she got Clermont promoted to Ligue 1 before that. Just so she could stick up two fingers at her critics, and that player who wrote her off when she joined.

The lack of flowers at her one hundredth game told a story of its own. Men don’t get flowers before landmark matches. Why should she be treated differently? Her adaptability is complete. Right now, Diacre is one of the longest-serving coaches in Ligue 2. Michy has ignored the conscious bias in the football industry and made a creative decision to hire a coach who gives his team an edge. We could all learn from that.

Michy is more hands-off in his running of Clermont Foot 63 than any other owner I have met in football. That is part of his skill. Later in this chapter, I will learn that stepping back and not interfering in the process is one of the best ways to allow creativity to flourish. At least, that works for one of the most talented youth coaches in football today. I am heading back to England, to meet the Liverpool academy chief whose job is to find the new Steven Gerrard.

HOW TO GET AN EDGE – by CLAUDE MICHY

ALEX INGLETHORPE

Allow creatives to flourish

Creatives need principles / Adapt and Recover, or Die / Intrinsic motivation and the Creativity Maze / Lessons from maverick Townsend / Woodburn and interference factor

As you walk past the main pitch outside the entrance of Liverpool Football Club’s youth academy (address: The Liverpool Way), there are banners of former players affixed to each lamppost. The first you see is Jamie Carragher, next Jon Flanagan, then Steven Gerrard, whose picture is closest to the main entrance, and finally Raheem Sterling. All four came through this academy. They are constant reminders to the youngsters who come here – from age five upwards – of what can be achieved.

In the past, this academy has been a battleground between its head coach and Liverpool’s first-team manager. In 2007, Steve Heighway, the former Liverpool player who played in their glorious era of the 1970s – winning four league titles, two UEFA Cups and two European Cups – was ousted as academy manager after falling out with then-coach Rafa Benitez. Since then, Piet Hamberg, Pep Segura and Frank McParland have all come and gone as Liverpool’s academy manager.

The role has become a political hot potato, not helped by the fact that the Kirkby site, next to a David Lloyd tennis centre on the outskirts of the city, is a ten-minute drive from the first-team training ground at Melwood. As one Liverpool-based writer put it: ‘The quest for absolute control or the protection of fiefdoms has ultimately prevailed at the cost of productivity.’12 Jamie Carragher, more bluntly, said: ‘When personalities don’t like each other, they hope the other person doesn’t do well. Do I think Rafa wanted Liverpool to win the FA Youth Cup? Probably not. Did people at the academy really want Liverpool to be flying under Rafa? Probably not. When a relationship breaks down like that, the club suffers.’

This is the context behind the role that Alex Inglethorpe took when he was appointed academy manager in August 2014. Those four banners mean his job is far more emotive than the title. He is looking to identify, nurture and develop players for the first team. In short, his job is to find the next Steven Gerrard for Liverpool. No pressure, then.

Inglethorpe is suited to the task. He is thoughtful and reflective, takes notes during our time together and admits he doesn’t have all the answers. Even if you might remember Thomas Tuchel saying the same thing, this is still a rare admission for people who work inside football clubs. He enjoys having his ideas challenged.

During our wide-ranging conversations, he explained his methodology behind unlocking creativity, motivating millennials, communicating with digital natives, and the importance of promoting authenticity, empathy and happiness in the workplace.

One of Inglethorpe’s first moves was to bring Heighway back into the fold (and another former youth coach, Dave Shannon), while it was lost on no one that Liverpool coach Jürgen Klopp spent his first full day in charge of the club watching an Under-18s match from the balcony overlooking the main pitch at Kirkby. In spring 2017, it was confirmed that the senior team would train on the same site as the youth structures. Inglethorpe was also involved in the decision to bring Steven Gerrard back to the academy to start his coaching career. Who better to help him find the new Gerrard than the original one? The former Liverpool captain speaks highly of Inglethorpe, who has told him about the importance of his body language and his coaching voice, which he wants to carry the same power as when he was Liverpool captain. ‘He has been honest and straight with me,’ said Gerrard. ‘He’s been first-class.’

Inglethorpe’s three years in charge of the academy are beginning to bear fruit. In the 2015–16 season, Klopp’s first at the club, nine academy graduates were given first-team debuts.13 In 2016–17, there were another four, three of whom – Trent Alexander-Arnold, Ovie Ejaria and Ben Woodburn – have made the move to Melwood full-time.14 This is a ringing endorsement of the work done by Inglethorpe and his academy staff.

Many coaches in England develop talent as a stepping-stone, part of the process, to becoming a senior first-team coach. Inglethorpe is different. His was a proactive decision to focus on development rather than be a head coach. He had played for Watford (for whom, bizarrely, he once scored a pre-season goal against Östersunds FK, the Swedish team we met in Chapter 1), Leyton Orient and Exeter City. His coaching career began at Leatherhead, and he was in charge of Exeter City when they drew 0–0 with Manchester United in a 2005 FA Cup tie. He turned down offers from MK Dons and Brentford to be their coach. He would have got more money and more prestige, but felt he was better suited to developing talent.15 Instead he moved to Tottenham Hotspur and worked under academy head John McDermott. He describes it as ‘my Harvard education’. That decision encapsulates him. He knows his strengths. He thinks before he speaks. He doesn’t waste words. He has an unflappable quality about him.

And he is honest: whether it’s admonishing one of the better Under-16 players in front of his team-mates for making a lazy foul in the last minute that could have led to a goal, or announcing to a packed dressing-room that an Under-15 triallist would be given a contract (normally that happens in a quiet meeting with parents present, but he felt the emotional contagion from the good news would infiltrate the squad, and it did).

He does not expect the players to like him. Respect is far more important; and he measures that by former players who have made it to Premier League level and who still keep in touch. Those who played in the 2016–17 Premier League season include: Adam Smith (Bournemouth), Jake Livermore (Hull City), Ryan Mason (Hull City), Danny Rose (Spurs), Harry Kane (Spurs), Andros Townsend (Crystal Palace), Tom Carroll (Swansea) and Harry Winks (Spurs).

His definitions of talent and creativity provide the perfect starting-point for our discussion. Like Ralf Rangnick, he defines talent as a mathematical equation:

Potential + time + opportunity – interference = Talent

Creativity, as he sees it, is deviation from the norm. In his words: ‘An ability to go off script.’ When he watches most matches, he can see where the best pass should go, or would normally go, but once in a while, a player will come along and not follow the script. ‘Sometimes that can leave you thinking, “Where did that come from?”’

‘The danger with that level of creativity is that it can be stifled at a young age,’ Inglethorpe says. ‘It can be coached out of you if you’re in the wrong environment.’ The coach draws a line between the need for rules, a rigid structure that takes away options and makes the game-situation less complex, and the need for principles, which relate to behaviour, approach and work ethic. He talks to his coaches a lot about this difference; which players and staff need rules and which need principles. Creative talents work better with principles rather than rules. ‘We are very wary, as we do not want to be a limiting factor to talent. We do not want to be a hindrance.’

This sense of freedom is vital for the creative. Ed Catmull, head of Pixar Animation Studios, wrote as much in a business article that was a precursor to his 2014 book Creativity Inc. A strong believer that talented people trump great ideas, he demands an environment ‘that nurtures trusting and respectful relationships and unleashes everyone’s creativity’. Pixar’s operating principles (not rules), he continued, were that everyone must have the freedom to communicate with anyone; it must be safe for everyone to offer ideas; and to stay close to innovations happening in the academic community.16

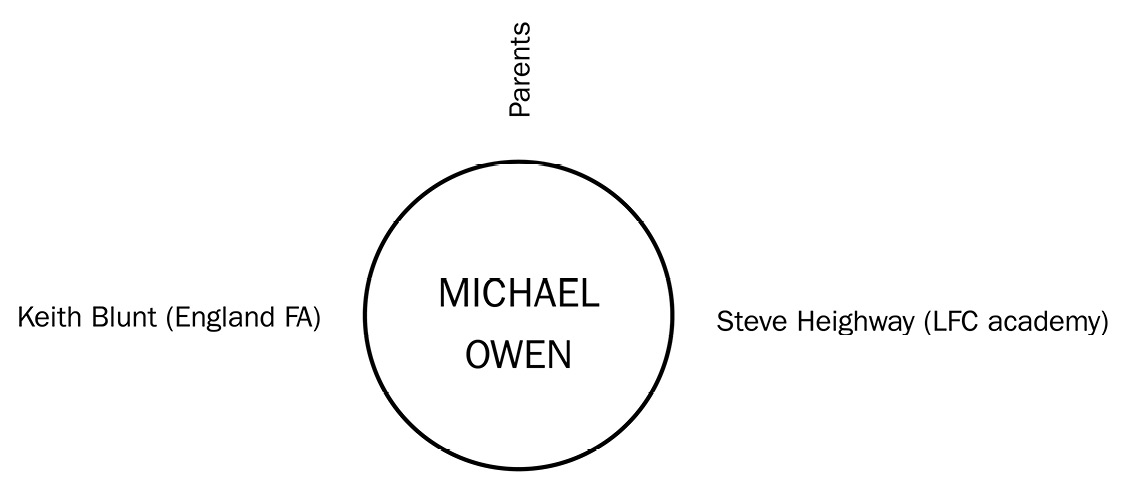

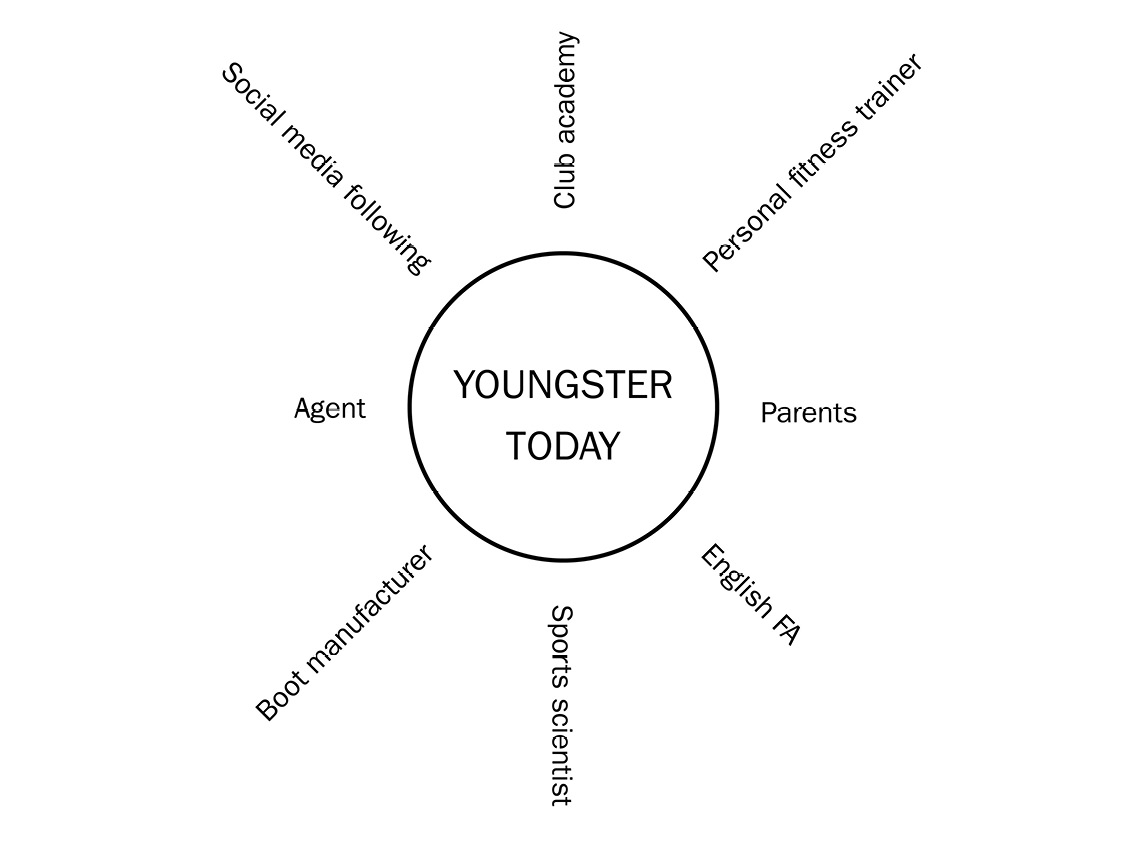

Inglethorpe draws me a diagram of the people that were around Michael Owen when he broke into the Liverpool team aged 16 back in 1996.

Alongside that, he draws a circle of a highly rated 16-year-old currently playing for a rival club.

‘Look at all that information he has coming into him!’ Inglethorpe says. ‘It’s from different people, with different agendas, all wanting different things. How is he going to be able to concentrate on football without that consistency of message? Or at least, how much energy is he going to devote to sifting through all that information? And most of all, how will he be able to enjoy it? The interference can come from other parties, like agents, parents, friends, as well as coaches. But it’s very important to manage. Because too much interference can put you in the black hole.’

No one wants to be in the black hole. Inglethorpe pulls out a slide on his laptop. At the top is written: ‘Adapt and Recover, or Die.’ Going up along the left margin are five career stages in talent development: Innocent Climb, Personal Agreement, Breakthrough, Mastery and The Higher Plane. Each stage has an arrow which points to a black hole on the right-hand side. These represent the pitfalls which can lead down the hole and need to be avoided. As we go through each one, the names of players pop into my head of those who fell along the way.

The challenge for every player is to adapt and recover at each stage. The dangers? One is the ‘Disease of Me’, which refers to players’ inability to put the team first: resenting team-mates’ success, or feeling paranoid, frustrated or under-appreciated even at moments of success. Another is ‘The Choke’, for those who lack the psychological strength required to reach the next level. Inglethorpe knows lots of good players who have not been able to make the step up because of their response to pressure. ‘The ability to play at Anfield is ultimately down to how you think and approach the enormity of what you’re doing.’ The next pitfall, ‘Complacency’, is the ‘made it already attitude’ of hubristic pride that we learned about in our visit to Salzburg in Chapter 4. There are also ‘Thunderbolts’: unpredictable factors like a career-ending injury or long-term illness.

The social support study carried out by Nico van Yperen at Ajax (Chapter 3) told us that a strong support network was a predictor of success. But too much influence can have the opposite effect. The Chelsea psychologist Tim Harkness explained to me what he felt was a key difference between elite performers and the rest: ‘One of the differences is that successful people just have more energy. They are still hungry and driven to succeed. The other is their ability to manage the circumstances that influence your motivation. Some people are hungry. Some people are strategically good at managing their influences. A very small number are good at both. If you want to be an elite footballer you have to be good at both, that’s what can really separate you from the pack.’ It’s a way of getting smart with the motivation resources that you have.

Inglethorpe makes it his business to understand the players’ triggers for optimal performance. ‘I need to know what buttons to push for every single one of them.’ That’s a lot of information to take in, given there are 170 players in the academy (this figure has come down from 240 when Inglethorpe took over, as he is looking for quality over quantity).

He tells me about one of his Under-18 players, who was struggling for a time last season. It was obvious to see and the coach brought him in for a chat. The youngster always had a ball in his rucksack, and was under-performing because he had stopped playing his favourite game, which was two-on-two football with his best mates in a tiny garage near the block of flats where he grew up. As a creative player, he was able to learn, improvise and practise moves in such small spaces. It was also football as pure enjoyment, not work, and away from the homogenised atmosphere of an academy environment.

Over a period of several conversations, Inglethorpe understood this was at the core of the player’s blockage. So he suggested that he carry on playing his two-on-two. ‘Your head says that if a player is this talented and 18 years old, you should not let him play garage football. The sports scientists would say no, the medics would say no. But you need to be intuitive and sometimes just understand what’s best for the individual. This is not based on a performance model, it’s a development model.’

It was also a calculated risk. Inglethorpe wanted the player to remember what made him unique, and encouraged him to tap into his own authenticity. It’s similar to the 2015 Converse ‘Made by You’ advertising campaign, which showed over 200 portraits of Chuck Taylor sneakers personalised by creative customers worldwide.17 Some had been coloured with rainbow stripes; others had hearts or messages painted on the toes; others were scuffed in an original way. All were celebrating individualism. Inglethorpe likewise wanted this youngster to celebrate his own individualism. The player went back to his garage game. The confidence boost was immediate and, not long after, he made his debut for the Liverpool first team. He is now a regular with the Melwood group.

There are a few factors going on here, so let’s break them down. The first is interference. Inglethorpe understood instinctively that giving the player autonomy in the development process would help his creativity. Second, the coach also showed empathy, simply by spotting that his player needed assistance and offering it. By making that first move, he showed that he cared. Third, he communicated his message in a clear and concise way. Now for a closer look at these factors.

First, interference: we have explored the difference between process and outcome in Chapters 2 and 3. Thomas Tuchel wants his team to represent a certain spirit regardless of the result. The AZ Alkmaar coaches tell their players which mountains to climb but not necessarily how to climb them. A clearly specified goal can aid creativity, but too much interference can be harmful.

Harvard professor and creativity expert Professor Teresa Amabile sums this up by explaining the Creativity Maze. There is a reward in the middle in the maze. Someone outcome-oriented would rush through the maze as quickly as possible, maybe taking obvious paths that have been used before, to get the reward. This approach is based on extrinsic motivation, a reward that is outside of the individual. It could be money, status, or even just avoiding the sack. The intrinsic motivation approach is about the process. It will probably lead to more errors. It may take longer. But the route in the maze would be more interesting, and the ultimate solution more creative.

‘People will be most creative when they feel motivated primarily by the interest, satisfaction and challenge of the work itself – and not by external pressures,’ says Amabile. Creative people have stronger intrinsic motivation. Albert Einstein described it as ‘the enjoyment of seeing and searching’. Michael Jordan loved basketball so much that he had a clause in his contract that he could play a pick-up game whenever he liked.

Other companies are taking note. A study by the University of Warwick asked 700 participants to add a series of five two-digit numbers in ten minutes.18 Some were then shown a ten-minute film based on comedy routines performed by a British comedian; or they were treated to free chocolate, drinks and fruit. The film, and the free snacks, succeeded in raising reported happiness levels of those who saw it, and improved their productivity. They found that happiness led to a 12 per cent spike in productivity, while unhappy workers were 10 per cent less productive.19

One Brighton-based conference business set up a Happiness Index for its employees with three buckets and a load of tennis balls. At the end of each day, everyone would take one ball and put it in one of two buckets: H marked happy or U marked unhappy. Not exactly sophisticated: but the results were collected every night and over a period of months, the company’s collective emotional temperature was taken. It turned out that Tuesdays tended to be a bad day.

Inglethorpe gets it. His staff love what they do so much that he has to beg them to take more time off. ‘The best places of work are the ones where you don’t see it as work,’ he says. That is intrinsic motivation. He has it, and it’s important that the creative talents also have it. They need it the most.

Intrinsic motivation is the main reason behind Liverpool’s decision to cap salaries for first-year professionals (i.e. for 17-year-olds) at £40,000 per year. They believe this policy of ‘delayed gratification’ will benefit the players in the long term. Southampton and Spurs do the same, while other Premier League clubs have reportedly offered contracts to 16-year-olds worth over £500,000 per year.

‘Think back to when you were 17 and how you would have handled a huge salary, plus a lot of time on your hands, and getting recognition from people around you. Would that have helped you fulfil your potential?’ Inglethorpe asks. (Thinking back, I struggled at that age without any of those things.) ‘We are trying to limit certain parts of the equation to help the player fulfil his potential.’ The lower salary should weed out athletes with extrinsic motivation who could earn more money elsewhere.

Inglethorpe has also learned from experience. His period working with Andros Townsend at Spurs informed his response to this particular Reds youngster. He remembers Townsend fondly as ‘an off-the-chart maverick in his approach’. Townsend was single-minded and obsessive in his approach to self-improvement. He would ignore advice to rest from sports scientists. He would hide a ball in the bushes behind the training pitch at Spurs and then play for another two hours with Tom Carroll and Jon Obika. He was stubborn and had no fear of failure. But he also had extremely high levels of intrinsic motivation.

‘He taught me a valuable lesson,’ says Inglethorpe. ‘He needed to get it wrong more than he got it right, and that approach worked for him. Andros got the best out of his talent, and he showed me there is more than one way to do that.’

It was not just the lack of interference that helped Townsend. (Of course Inglethorpe knew about the ball in the bushes, but he never took it away or forbade Townsend from playing.) It was also empathy, as the coach also provided an emotional support to allow that fearlessness to remain. Even if senior Spurs players like Dimitar Berbatov and Robbie Keane would get frustrated when he didn’t pass, Townsend was never afraid to fail with a dribble. A few days before Inglethorpe told me this story, the winger had scored a goal for Crystal Palace that summed up this attitude: running from inside his own half to score in a crucial win against Middlesbrough. ‘Maverick talents take more risks so there is more chance of them failing,’ he adds. ‘But the upside is always greater.’

This is about care. Caring for the body gives a player an edge. But care from managers, particularly in the form of emotional support, is a huge driver in performance. The presence of a caring environment allows you to take risks and innovate without fear of failure. Geir Jordet also believes that helping a team-mate during a game can take your mind off your own pressure and so enhance your performance

Anthony Knockaert would agree. The Brighton winger was devastated when his father died in November 2016. Two days later, captain Steve Sidwell celebrated scoring a goal from the halfway line by running to the touchline and holding up Knockaert’s shirt (Knockaert was absent on compassionate leave). The next week, coach Chris Hughton and 14 of Knockaert’s team-mates crossed the Channel to pay their respects at the funeral near Lille. ‘When one of our team hurts, we all hurt,’ tweeted goalkeeper David Stockdale with a unique team picture: the whole squad wearing black suits outside a church. Knockaert was blown away: ‘When I say it was the best moment for me in my life, I hope you know what I mean,’ he told The Times. ‘My family were so proud, they realised how good this club is, the best I’ve been at.’

This is also becoming a priority in business. The Empathy Business rates companies that successfully create empathetic cultures based on their ethics, leadership, company culture, brand perception and public messaging through social media. The rankings correlate empathy to growth, productivity and earnings per employee. Those companies with high rankings also have high retention rates, environments where diverse teams thrive, and are the most financially profitable. In 2016, Facebook, which had recently established an ‘Empathy Lab’ devoted to building accessibility features into the site for blind, deaf or otherwise disabled users, topped the Empathy Index.20

I notice a similar level of care in the smallest exchanges at the Liverpool academy. During a short walk from Inglethorpe’s sparsely equipped office overlooking the training pitches to the canteen, he greets every youngster he sees by name.21 He expects the same in return. He sees a 15-year-old from Spain about to eat, and asks him how he’s getting on. ‘Good,’ says the boy. ‘What’s on your plate?’ asks the coach. ‘Rice, vegetables and, um …’ ‘Those are prawns,’ says Inglethorpe. ‘Well done. Your English is getting a lot better. Great stuff. Enjoy your meal.’ The boy beams and tucks in.

The third factor, after interference and empathy, is communication. Didier Deschamps told us about the art of listening in Chapter 2, but managing millennials is no easy task. Jens Lehmann once told me about his brief spell with Arsenal’s reserve side as a 40-year-old back in 2011. In the team coach on the way to a game he was surprised by the total silence. ‘No one was talking,’ he said. ‘I thought, “Has everyone gone to sleep?” But then I looked around. Everyone was on their phones, typing away on Twitter or Facebook. They were all hanging on their devices and I think this has a major impact on communication.

‘These kids are not used to quick language commands and all their time on the phone makes them incapable of quick commands on the pitch. They text instead of talk and that means they are not quick thinkers any more. I really do think this is influencing the games now: we have to teach them how to communicate on the pitch. I know of some players who have been told to get off Twitter as they are addicted.’

One coach told me that his goalkeeper spends so much time looking down at his device that it is actually affecting his spine. He fears that the player will decline much quicker than other goalkeepers as a result.

Social psychologist Sherry Turkle, author of Alone Together, argues the muscles in our brain that help with spontaneous conversation are getting less exercise than ever before, and therefore our communication abilities are declining. One 18-year-old boy came up with something she found interesting. ‘Some day, but not now, I’d like to learn how to have a conversation,’ he said. ‘Why not now?’ she asked. ‘Because it takes place in real time and you can’t control what you’re going to say,’ he said.

‘Our devices are so psychologically powerful they don’t change what we do but who we are,’ Turkle said. ‘It matters because we set ourselves up for trouble in how we relate to each other and how we relate to ourselves and our capacity for self-reflection. Our devices give us the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship … If we don’t teach our children how to be alone [without devices], they will only know how to be lonely.’

Liverpool deals with this problem by telling all players in the Under-18s and above to hand in their mobile phones when they arrive, and they can only pick them up after they leave. ‘They have to learn to communicate,’ says Inglethorpe. He draws a crucial distinction. ‘It’s only harder for leaders to communicate with them if you choose for it to be harder. They are a different generation in the way they communicate with each other, but if you are prepared to make the time to sit down and have a chat, I don’t know a single player that would not appreciate that. It’s wrong for us to assume that generation do not want an old-fashioned face-to-face chat. They do want it and respond well to it.’ Smartphones are kept out of sight, as they are in coaches’ meetings as well. This is a lesson out of the Deschamps’s playbook. Both recognise that having devices out of sight leads to more fulfilling interactions.

Dr Sherylle Calder, a South African vision specialist who has worked in American football, golf, motor racing, rugby, and in the 2016–17 season with the Bournemouth goalkeepers, advises that less screen time improves players’ decision-making.22 ‘When you look at your phone there are no eye movements happening and everything is pretty static,’ she says. ‘In the modern world the ability of players to have good awareness is deteriorating.’ She argues that we develop instinctive natural skills by climbing trees, and walking on and falling off walls. Spending time on devices weakens those skills. ‘If you don’t see something, you can’t make a decision. One of the skills we work on is being able to see, or pick up, something early. The earlier you see, the more time you have to make a decision.’

I am reminded of a picture that, ironically enough, went viral minutes after Argentina had beaten Venezuela 4–1 in the 2016 Copa America semi-final. Argentina, who had not won a major trophy since 1993, was one game away from ending this 23-year drought. It was taken by Argentina defender Marcos Rojo and posted by team-mate Ezequiel Lavezzi on Instagram, with the caption: ‘You’ve just finished playing a game and …’

There are seven of them, sitting on the dressing-room bench. All have their boots off, some have taken off their socks or their shirts. Collectively, they could make up one of the finest five-a-sides (plus two subs) in history: Lionel Messi, Sergio Aguero, Lavezzi, Gonzalo Higuain, Javier Mascherano, Jonatan Maidana and Ever Banega. Not one of them is looking at anyone else. No one is speaking. They are all looking down, at their phones. In their own world; together, but miles away; present, but absent. ‘This is the national team 2.0,’ joked one newspaper, Olé, while a writer in Clarin pointed out: ‘If phones are our full-time companions today, why shouldn’t they be for footballers too?’ The only people who weren’t happy with the picture were Venezuelan fans, as some of their players’ shirts can be seen strewn on the dressing-room floor. Lavezzi was happy: his picture got 147,000 likes. Argentina went on to lose the final, on penalties, to Chile.

Another image from a game in November 2016 sticks in my mind. Liverpool had just beaten Leeds United 2–0 in the League Cup quarter-final and two players are walking off the pitch, smiling at each other. There is an ease in their movements, comfort in their company; each one is chuffed for the other. There is nothing lonely about this moment. Communication does not seem to be a problem.

These two might be the next players whose image will be on the lampposts overlooking the academy main pitch: one of them is Trent Alexander-Arnold, the 18-year-old right-back whose whipped cross from the flank set up Divock Origi for the opening goal.23 Ben Woodburn, the other player, is even younger. He was making his second appearance for the first team and scored a goal at the Kop end, where Liverpool’s loudest support sits. At 17 years and 45 days, Woodburn had just become the youngest ever scorer in the club’s history. It was an incredible moment. ‘Roy of the Rovers stuff,’ says Inglethorpe, who watched the match with the Under-18s team at the stadium. ‘It was wonderful to be around them when Ben scored.’

I had first heard of both players a few months earlier, sitting in that academy canteen with Inglethorpe and his colleagues. As we all ate pea soup, they were talking about players with talent. ‘But do they have an edge?’ I asked. The answers were unanimous. Woodburn, particularly, seemed destined for the top. They spoke of his quiet determination. His will to win. Cool under pressure. Ice in his veins. Reacting well to team-mates losing the ball, or when he misses chances. He had been fast-tracked through the club: at 15 he had played for the Under-18s and then as part of the Elite Youth Group that trained with the senior team at Melwood once a week. Now he trains there every day. He doesn’t want that goal to be the defining moment of his career. A few months after that goal against Leeds, he was called up to the senior Wales squad.

‘You’re more nervous around a highly talented boy, so the best thing is to give him the freedom to develop,’ says Inglethorpe. ‘The skill of a coach is to know when to push and when to provoke. Sometimes the best way to manage a creative talent is to leave them to it.’24

In the cases of Woodburn, Alexander-Arnold and Ejaria, this is no longer a choice for Inglethorpe. They have moved on to Melwood. They are all one step closer to their dreams. Inglethorpe is one of the coaches who helped make it happen, and he will still be there for them, if they need him. He certainly still cares. There’s also the next generation to consider, which includes an exciting teenage creative talent called Rhian Brewster. He has a long way to go. As long as Inglethorpe is running the academy, he is in good hands: with a specialist who understands how to give young talent an edge.

Inglethorpe is coaxing the best out of potential but what about the manager who is dealing with established talent? I wanted to ask someone who has been part of a team that contained a genius talent how best to unlock creativity. I knew just the man: a World Cup winner, former team-mate of Diego Maradona and a successful coach with Real Madrid. My final appointment on this quest for an edge was with Jorge Valdano.

HOW TO GET AN EDGE – by ALEX INGLETHORPE

JORGE VALDANO

Make room for the maverick

Progressives reject mainstream / Football reflects life / Conditions for talent growth / Team as state of mind / Optimistic leadership and The Happy Film / The connectivity curse / The genius transaction

Jorge Valdano tells a neat story about Diego Maradona’s second goal against England in the 1986 World Cup quarter-final. Maradona dribbled from inside his own half past a series of lunging England defenders and stroked the ball past the goalkeeper, Peter Shilton, to secure a famous victory. It remains one of the greatest goals ever scored, and Valdano had the best view of it.

Valdano was Maradona’s Argentina team-mate at the time, and was running alongside Maradona waiting for him to pass the ball. ‘Why didn’t you pass to me?’ he asked Maradona after the game. Maradona told him he had wanted to, and was watching Valdano while skipping beyond each challenge, but the defenders kept coming, and before he knew it he’d beaten them all and scored. Valdano couldn’t believe it. ‘While scoring this goal you were also watching me? You insult me. It isn’t possible!’25

Valdano’s moment of glory came in the final. He scored the goal that put Argentina 2–0 ahead against West Germany. At that point, he realised the enormity of the moment, and started watching the game like a fan. Before he knew it, the score was 2–2. As Argentina kicked off to restart the game, José Luis Burruchaga turned to Valdano and Maradona and said: ‘We’re feeling good, aren’t we? No problem, this one’s in the bag.’ Two minutes later, Burruchaga scored the winning goal.

Valdano played for Real Madrid at the time. He had been voted Overseas Player of the Year for that season. The team, five of whom were developed in the club’s academy, won five league titles in a row from 1986 to 1990. The pick of the bunch was the charismatic Emilio Butragueno, whose nickname El Buitre (‘The Vulture’), spawned the team nickname La Quinta del Buitre (‘The Vulture’s Generation’). Valdano added experience and goals to this mix.

Valdano later became Real Madrid coach – giving a debut to a willowy 17-year-old called Raúl – and, twice, sporting director of the club (from 2000 to 2004 and from 2009 to 2011); he was in charge when they bought David Beckham, Zinedine Zidane and Cristiano Ronaldo. Although Real Madrid is still identified with General Franco and considered a right-wing club, Valdano, a former law student who is now a columnist, commentator, author and management consultant, is proudly left-wing, although he prefers the term ‘progressive’.

‘A progressive approach rejects the mainstream belief that organisation takes precedence over freedom, that the collective counts for more than the individual,’ he once said. ‘It rejects the notion that the coach’s ideas outweigh those of the players, and fear neutralises attacking instincts.’26

This is why I want to ask Valdano about talent and creativity, and how he finds an edge in rejecting ‘the mainstream belief …’. Take his first-ever game as a coach, in charge of relegation-threatened Tenerife: his first-choice defence, all four of them, were unavailable (injured or suspended). The club owner, a local gynaecologist called Javier Perez, offered to buy Jorge Higuain (Gonzalo’s dad) to shore things up at the back. Valdano said no. Instead, he fielded two wingers at full-back, and two attacking midfielders at centre-back. Tenerife won 1–0.

That team had looked doomed when Valdano took over with eight games left to play. ‘It was crazily unwise by me,’ he admitted later. ‘It could have compromised my career as a coach and my credibility as a commentator. I had everything to lose but also wanted to be a coach and had the conviction that I could adapt my ideas to the characteristics of the team.’27

Tenerife were safe before the last day of the season. Final-day opponents Real Madrid needed to win to be crowned champions, and were 2–0 up at half-time. Valdano told his players that they would be the centre of the football world if they turned it around. They did, and won the game 3–2 – which meant that Barcelona won the title. The rest of Spain declared Tenerife true champions.

‘The coach de-blocked us mentally,’ said Tenerife’s attacking midfielder Felipe Miñambres. ‘He taught us to dare, to no longer have fear, to take risks. We would have followed him anywhere. We believed everything he said. He made us feel invincible.’

The same thing happened the very next season: Tenerife beat Real Madrid on the last day, helping Barcelona win the title.28 Tenerife also qualified for the UEFA Cup. After Tenerife beat Real Madrid in the Copa del Rey semi-final in the following season, the capital club had had enough. They hired Valdano as coach. He won La Liga in his first season in charge.

Valdano explains that he was a coach who always looked for greatness. ‘It was based on my desire for efficacy, courage and beauty – even though I wasn’t judged on those factors, but was actually judged on my results.’

He remains a romantic. For him, process outweighs outcome. He loves the art of improvisation. Creativity matters. Mavericks should succeed. That’s why he wrote a column in Marca, Spain’s best-selling newspaper, bemoaning the goalless 2007 Champions League semi-final between Liverpool and Chelsea as ‘shit hanging from a stick’. His view? ‘The extreme control and seriousness with which both teams played the semi-final neutralised any creative licence, any moments of exquisite skill … Such extreme intensity wipes away talent, even leaving a player of Joe Cole’s class disoriented. If football is going the way Chelsea and Liverpool are taking it, we had better be ready to wave goodbye to any expression of the cleverness and talent we have enjoyed for a century.’

He also fully agrees that the business world has a lot to learn from football. ‘The analogies between the sport and business are fairly obvious. Companies need to earn money and achieve their targets. But the world we live in is full of frustration, anxiety and stress, all of which subverts these goals and strategies. In my view, football can offer solutions. Football helps us understand who we are. It reflects what is happening in our cities: the commercialism and the competition, the ugly and the beautiful aspects. And why is it so compelling as a metaphor? Because it is a world of exaggeration, of excess. It produces powerful images, images we can all relate to.’

Valdano is in a privileged position to teach us about getting an edge. He even set up a company, called Makeateam, which advised how to manage talent and discover the motivations within a team to optimise performance. Rather like this book, its aim was to improve businesses by offering real-life lessons from the football world.

As a player, team-mate, coach, sporting director, columnist and author, he has stuck to his view of football as an art form. Like Thomas Tuchel, he believes in the aesthetic (now there’s a conversation I would like to listen in on). It takes courage to think, to play, to coach and to write the way he does. When he said he could never have scored Maradona’s solo goal, but he can describe it better than his team-mate, he was establishing a difference between narrative intelligence (his own) and footballing intelligence (Maradona’s). ‘The first has more prestige but the second has more complexity.’ This is why his nickname, El Filosofio (‘The Philosopher’), is not meant ironically.

Before he tells me how to unlock creativity, I ask how he defines talent. ‘It’s a gift that chooses us,’ is his response. ‘A special facility that, cultivated properly, can distinguish us professionally. We know there are many ways for us to shine. The intelligence needed for painting is not the same intelligence needed for solving a maths equation or for playing football. And talent needs a proper environment. That cultural force pushes talent like no other force can. ‘Talent,’ he continues, ‘needs certain conditions to flourish:

Wherever he works, Valdano makes sure the people around him are confident. His job is to enhance his colleagues’ belief that they can perform beyond their expectations. It’s a mental trick that relates to one of his more famous quotes: ‘A team is a state of mind.’ What does that mean?

‘A team is a state of mind. That definition can be applied for any team: sports team, business team, political team, academic team … For example, I believe that a football coach needs to know about football but also about human beings. Knowing about football makes you value the knowledge, while knowing about human beings makes you value the emotions. In a technology company, the equation is the same: you need to know about technology but also about human beings. It’s the same in any organisation. A positive state of mind can work miracles in the performance of a team; a negative state of mind too, but the other way around.’

We have seen that businesses can improve results by improving the happiness of their employees. Optimistic leaders can also boost production by focusing on opportunities, finding solutions, and enabling collaboration and innovation.

The best form of optimism is what business leaders call ‘realistic optimism’. One study had a psychologist interview obese women in a weight-loss programme about how confident they were about reaching their goals. Those who were confident lost an average 26 pounds more than the self-doubters. The other difference was in who had ‘realistic optimism’ about their efforts. The women who believed it would be difficult to reach their target lost 24 pounds more than those who thought it would be easy. Optimism is one thing, but it has to be realistic. The psychologist behind the study, Gabriele Oettingen, found similar results applied to other areas of life: students looking for jobs after college, old people recovering from hip replacements, singles looking for love. The realism associated with the task led to higher success rates.30

Valdano has his own version of optimism. The best teams, he says, need passion; people who believe strongly in what they are doing. ‘People with such outstanding qualities that the realm of the team’s possibilities becomes as wide as possible. I say that because people normally look for faults first and choose those who don’t have any.’ Valdano prefers to focus on the positive. ‘I choose the outstanding quality [first] and normally I fall in love with that because that gives you the enthusiasm to help those around you to improve.’

Valdano also warns that you need time to work on state of mind. He recommends a change of scenery. To aid his creative thinking, he takes proper time off from football every three or four years and it does him the world of good.

He is not the only one: Stefan Sagmeister, a double Grammy-winning New York-based designer who has made album covers for the Rolling Stones, Jay-Z, and Talking Heads, makes everyone in his design studio Sagmeister & Walsh take a year off every seven years as a way to enhance their creativity. During one such break, he was designing furniture in the Balinese town of Ubud. A friend joked that all he had to show for his amazing experience was some beautiful chairs – and so what? Sagmeister asked himself the same thing.

Sagmeister, a controversial figure in the design world, wondered if he could train his mind to be happier.31 He wanted to take time to really explore what can make us happy, and even change his personality to become a better person. He made a film about his quest, which turned into a seven-year odyssey that, as he put it, ‘attracted every possible catastrophe I could imagine. Working on The Happy Film made me profoundly unhappy.’ The result was an ambiguous, funny, sad, sensitive and honest picture of a man trying to be a better person.

It was also a success. The Happy Show, originally conceived as an extension of the film, has become the world’s most visited graphic design exhibit, showing in nine different cities.32

Sagmeister is an optimistic leader in the Valdano mould. He recently argued with his older sister over who was the more optimistic. (His nieces broke it up and said they would be the judges. It was a tie.) His method of unlocking creativity comes from the philosopher Edward de Bono, who suggests starting to think about an idea for a particular project by taking a random object as point of departure. Sagmeister gives the example of a pen, and looks around his Japanese hotel room for a random object. ‘Bed spreads! So, bedspreads are … sticky … contain bacteria … ah, would it be possible to design a pen that’s thermo-sensitive, so it changes colours where I touch it. That would be nice, and not so bad considering it took me all of 30 seconds. This works because the method forces the brain to start out at a new and different point, preventing it from falling into a familiar groove it has formed before.’ This is Differential Learning, by a different name.

Sagmeister is a fair-weather Bayern Munich fan, only because his great friend Bobby Dekeyser was briefly on their books. Dekeyser became a successful entrepreneur himself, his luxury furniture brand DEDON making him millions and selling to the likes of Uli Hoeness, Michael Ballack, Brad Pitt and Julia Roberts. ‘We invented the outside living-room,’ he said. The secret to his success was ‘The Bobby Principle’, of keeping his employees happy. He offered free health care and travel to work and a sports instructor every night for different tuition. He also engaged employees in his social purpose, among which is to help people on the Philippine island of Cebu build sustainable lives.

The main purpose of Sagmeister’s sabbaticals is to make sure that the work remains a calling, ‘and does not deteriorate into a job’. I ask him if we are too connected to be truly creative. With smartphone addiction filling up spare moments, those opportunities for inspiration become increasingly rare. Who has ever had a great idea while checking emails in a restaurant, clicking on cat memes or watching a Donald Trump gif?

‘The problem itself is not that I am too connected, the problem is that I use this available connectivity as an excuse for being too busy to do real work,’ Sagmeister replies. ‘It is just so much easier to answer a couple of emails, do some Skype calls and reply to texts, than it is to sit down and actually, properly, think. The problem is not the technology, the problem is me.’ Given that around 75 per cent of Americans use their phone in the bathroom, and 25 per cent of Brits let their device interrupt sex, I suspect he is not alone.

HOW TO GET AN EDGE – by STEFAN SAGMEISTER

Thomas Tuchel took a sabbatical in 2014 after his five years at Mainz and before he joined Borussia Dortmund. At the start, he felt under pressure to travel the world in a camper van, but he soon enjoyed a slower and less scheduled way of life. He booked a two-week family holiday in Italy and ended up staying for eight weeks. He was able to enjoy other cultures: going to gigs and, on the recommendation of an 80-year-old he met at the local swimming-pool, visiting Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum to see the work of Pieter Bruegel.

‘I had the time to discover artists and musicians and to get to know different people,’ Tuchel says. ‘Also my neighbour – to sit and have dinner and listen to his ideas about books or other things. That can help keep things fresh in your mind and allow you to think about your talent, your destination and your journey.’ So would he take another sabbatical in the future, if required? ‘For sure, 100 per cent. And this time I would switch off for longer, and not think about the next job too early.’

Not everyone is in a position to take time off work to recharge, refresh and reinvent. But even some quiet time can help. Luciano Bernardi, an Italian doctor, discovered that our muscles and breathing are more relaxed by silence than by relaxing music. A 2013 study of work environments in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, based on a survey of 43,000 employees, concluded that the noise and distraction disadvantages of open-plan offices outweighed the anticipated, but unproven, benefits such as raised morale and productivity boosts from spontaneous interactions.33

Valdano believes that space and freedom allow creativity to flourish. ‘You put a limit on the possibilities of a child’s development if you cut their needs of expression.’ Like many South Americans, in football terms he believes ‘the street’ is the best teacher. In football schools, there is homogeny and an obligation to follow a model of learning. That leads to kids all running and playing in a similar way. Fine for the average ones. But for the special ones? ‘It’s terrible. The street respects spontaneity and doesn’t hold back those ones who are different.’

So how does a leader get the best out of a maverick talent in the workplace? ‘You need to be someone who first recognises the talent, but is also within a team who can live with a different personality. Geniuses aren’t always easy people to live with, but their contributions produce such a jump in quality that they deserve the collective hard work and support. That will put us in front of a true team, which is the one that strives for excellence starting from the collective intelligence. Some environments, like the world of technology, tolerate genius types much better than others. They perfectly understand that you cannot have adventure without risk.’

Argentina learned to tolerate its own genius. Before the 1986 World Cup final, all was quiet in the Argentina dressing-room. The biggest moment in the players’ lives was close. Everyone was nervous. Then Maradona started to cry out to his mother. ‘Tota, come and help me! I’m afraid, I need you to protect me!’ Maradona was sending a message to his team-mates: ‘Don’t worry if you’re afraid. I’m Maradona, and I’m afraid too.’ It worked – but Burruchaga’s realistic optimism also played a part.

Valdano is often asked how many geniuses you can realistically fit in a team environment. By definition, a genius is an exception. How many exceptions can you have inside your team? Maradona had his own whims, caprices and eccentricities. But it worked within the Argentina team. Why? ‘There is a transaction between the genius and the team,’ Valdano explains. He and his team-mates had to ask themselves if they were willing to accept someone so special. The answer was yes. In this case: ‘This genius will make me better and help me win a World Cup.’

Mavericks make others uncomfortable. They create conflict. They struggle with routine and, as we learned earlier, can be better suited to principles than rules. The chief executive we met in the Prologue, who runs his media business along the lines of his favourite Premier League coach, empowers his mavericks. ‘I’ve never met anyone truly talented who is easy to manage,’ he said. ‘I don’t tell them how I want them to work, but I tell them what success looks like.’

This can also cause issues. Another chief executive told me that managing the maverick is not always the problem; that just as much time needs to be spent managing the attitude of others towards the maverick. ‘Others will be constantly frustrated by them, so you need to help them see what the mavericks bring and that they are worth the pain and aggravation.’

Managers can intervene if the maverick upsets colleagues, to remind them of the shared goal; they can offer the empathy and communication that works for Inglethorpe at Liverpool; they can create an environment that welcomes risk and bravery. But Valdano’s method is much simpler: agree to the transaction, accept that the maverick will take the team to a better place, and it might even be fun, if a little scary, along the way.

Valdano urges discipline, professionalism and, above all, humility from those around the genius. There is no shame in not being the exceptional talent. Many people don’t even get to be part of a team with one. So if you are lucky enough to be in that position, says Valdano, be pleased and be humble.

I have learned that this also the best way to get an edge. It cannot come just from within. We all need support along the way, whether it’s from family, friends, colleagues, specialists – or mavericks. Our above-the-shoulder behaviour types can help maximise our talent and that of those around us. The football experts I spent time with during the course of writing this book have taught me that much; they have helped me, in different ways, develop my own edge. But none of us can do it on our own. ‘Ego interferes in the pursuit of collective success,’ Valdano reminds me. ‘You always need other people to succeed.’

HOW TO GET AN EDGE – by JORGE VALDANO