History of the Tai Chi Chi Kung Discharge Form

Discharge power is best known in Chinese as Fa Jin, which is translated as “discharge” or “transfer” of power (fig. 1.1). Fa means “to issue,” while jin translates as “internal force.” The word Fa Jin is thus used to describe the transfer of a large amount of momentum with seemingly little or no external strength. In contrast to Fa Jin, Li power uses external strength and gross muscular force. Li power requires outward telegraphing of movement prior to the strike, whereas Fa Jin does not.

Fig. 1.1. Chinese characters for Fa Jin

The first purpose of this chapter is to explore the use of Fa Jin—discharge power—in the history of internal martial arts within China. The second purpose is to understand the Universal Healing Tao Yang Discharge Form within this historical framework.

Discharge power is the ability of the practitioner to issue force or power without evident effort. This is the form of practice that is responsible for those legendary stories of Tai Chi Chi Kung masters hurling their opponents several yards away without even touching them. It involves the cultivation of power deep within and a calculated discharge of that power in a highly focused and carefully executed form.

Discharge power is featured in the three internal Chinese martial arts: Tai Chi Chuan, Ba Gua Zhang, and Hsing Yi Chuan. Tai Chi Chuan can be defined as a soft internal style of martial arts characterized by forms practiced in a slow meditative state of mind. Ba Gua is a style based on the eight trigrams of the I Ching. It has eight palms and is characterized by circular movements. Like Tai Chi, Ba Gua Zhang translates the spiritual aspects of Taoism into physical form. Hsing Yi or “heart mind” boxing involves a more direct, rapid, and staccato approach to fighting. Each of these disciplines draws on classic texts and methods to cultivate and express discharge power.

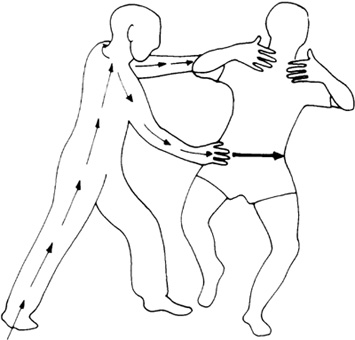

To understand the nature of discharge power it is useful to use the laws of physics, in which Power = Mass x Acceleration × distance within a unit of time (fig. 1.2). In the case of Fa Jin, mass is the weight of the opponent; acceleration is the change in velocity when the opponent is propelled; and distance is the measure of how far the opponent is thrown. Some practitioners are able to discharge huge power with the techniques described in this text.

Fig. 1.2. Power = Mass x Acceleration x Distance. The farther the throw, the greater the power.

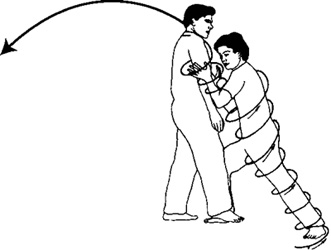

In martial arts practice, this power can occur with minimal external manifestation and seemingly minimal effort (fig. 1.3). Furthermore, it is not related to the youth or muscle mass of the practitioner.

Fig. 1.3. If the force is not grounded, it does not pass through the structure, and the body falls.

Power transfer can be used as a healing force or as a destructive force. When it is used as a healing force, it is called Fa Jia.*1 When power is transferred to exert a destructive effect on certain acupuncture points, it is called Di Mak.

THE HISTORY OF TAI CHI CHUAN

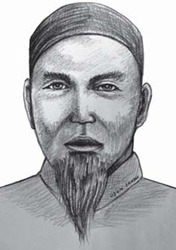

The practice of Tai Chi Chuan was allegedly created by Chang San-Feng (1279–1368 CE), a Taoist monk who lived at the Wu Tang Mountain—the site of many schools of internal martial arts training (fig. 1.4). Chang San-Feng had also studied at the Shaolin temple, but he reformed their external art techniques (Li power) to incorporate Fa Jin. The principle of including yin techniques in martial arts practice was a paradigm shift that led to notions of softness and yielding, and to the incorporation of slow, meditative forms.

Tai Chi Chuan is an internal martial art based on the philosophical and cosmological concepts of Taoism. The term Tai Chi is a philosophical term—arising from Taoist cosmology and creation theory—that is directly translated as “the supreme ultimate.” It represents the primal duality of yin and yang. According to Taoist cosmology, beneath the nothingness there is the Tao, and from the nothingness arose the yin and yang. The interplay of this duality to facilitate experience of the Tao is the reason why it is regarded as the “supreme ultimate.” The internal martial art of Tai Chi Chuan integrates with the philosophical and cosmological concepts of the Tao at many levels. The methods and experiences required to develop within the art of Tai Chi require a deep understanding of these concepts.

Fig. 1.4. Chang San-Feng

The Tai Chi Chuan Ching is regarded as the principal Tai Chi Chuan classic and is attributed to Chang San-Feng, though its true authorship is unknown. Many classics of Chinese thought are attributed to legendary immortals, though this cannot be proven in most cases. Perhaps adepts feel that they have been inspired by the forefathers of the discipline—or even that they have channeled the thoughts of the immortals—and humbly attribute ownership to them.

In the Tai Chi Chuan Ching, Chang San-Feng says:

Let there be no hollows or projections; let there be no stops and starts. Its root is in the feet, its issuing from the legs, its control from the yao (waist), and its shaping in the fingers.1

This passage highlights two basic principles of Tai Chi that are also fundamental teachings of the Universal Healing Tao system. The first principle is Iron Shirt training, which removes segments of tension within the spine and limbs. This tension correlates to the “hollows and projections” described by Chang. The second principle describes the passage of chi from the heels through the body and spine, which is the primary teaching of the foundational form of Tai Chi Chi Kung. It will be discussed in greater detail in chapter 3.

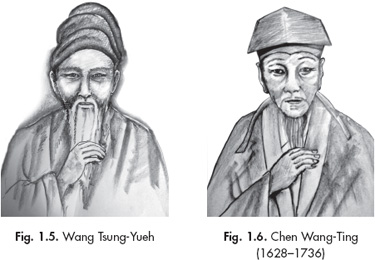

After Chang San-Feng there is a period of several hundred years during which both written classics and legendary Tai Chi masters seem to have disappeared. It is not until the likes of Wang Tsung-Yueh that the available history of Tai Chi Chuan resumes (see fig. 1.5 on page 6). The biography of Wang Tsung-Yueh is uncertain, though it seems that he was a teacher who lived in Shanxi province and taught in Honan province. His exact dates of birth and death are unknown. Chen village and Yang proponents have him existing prior to Chen Wang-Ting somewhere in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), hence his position on the lineage tree between Chan San-Feng and Chen Wang-Ting. However Douglas Wile questions this and has him living in the eighteenth century.2 His classic Tai Chi Chuan Lun marks the first verified Tai Chi classic.3

Wang comments on the cultivation of jin, saying:

Yin and yang mutually aid and change each other. Then you can say you understand jin (internal force).

The process of interaction between yin and yang energies—between the substantial and insubstantial—is found in the Universal Healing Tao Fusion practices and Kan and Li practice. Fusion practices involve the merging of the various yin and yang elemental forces. Kan and Li practice teaches us to invert yang (fire) beneath the yin (water) energy and then couple them together. This process creates a new energy, which is closer to the Primordial Chi. It creates an expansion in the tan tien, which is used to fuel the release of jin.*2

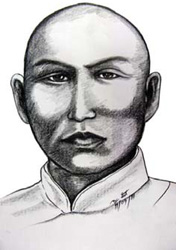

The oldest of the Tai Chi forms is the Chen style, which was developed by Chen Wang-Ting (1628–1736) in the Chen family village (fig. 1.6).4 Chen Wang-Ting is said to have learned Tai Chi from Jiang Fa, who had learned it from Chang San-Feng. Alternatively, some scholars believe that Chen Wan-Ting was the true creator of Tai Chi Chuan, rather than Chang San-Feng.5 There maybe a hidden agenda here, as proponents of this position may be seeking to add authenticity to the Chen family name, but in any case hard evidence of the actual existence and contributions of these legendary Tai Chi forefathers is difficult to come by. Nevertheless, the usefulness of the Tai Chi Chuan Lun and the Chen approach to Fa Jin is undeniable.

To this day, the Chen style carries several forms within its repertoire that make use of Fa Jin, including Cannon Fists, Buddha’s Warrior Attendant, and Light the Firecrackers. The external manifestation of these forms includes a sudden release of force through the physical musculature, which looks, to the naked eye, like a shaking at the end of the move.

The Yang style was an adaptation of the Chen style created by Yang Lu-Chan (1799–1872) (see fig. 1.8 on page 8). It is alleged that he spied on Chen Chang-Xing (1771–1853) and achieved his skills in discharge power this way.6 The Yang style is characterized by its more consistent tempo, which contrasts with the staccato rhythm of the Chen style. It is therefore aligned with Chang San-Feng’s principle that “Tai Chi Chuan is like a great river rolling on unceasingly.”7 Each move has that characteristic flow despite the fact that the moves are executed in various directions. The current long 108 form has no overt exhibition of Fa Jin, although the little-known Small-Frame Fast Tai Chi form does. (The Small Frame is a compacted long form that is executed with speed.) Nevertheless, each form in the long form can rehearse and create familiarity with the principles of Fa Jin. On this point, Wang Tsung-Yueh reminds us that “from familiarity with the correct touch, one gradually comprehends the jin.”8 The use of jin begins with the closing of the arms, which assists in the contraction of the tan tien and its consequent expansion, followed by the passage of chi through the spine and structure.

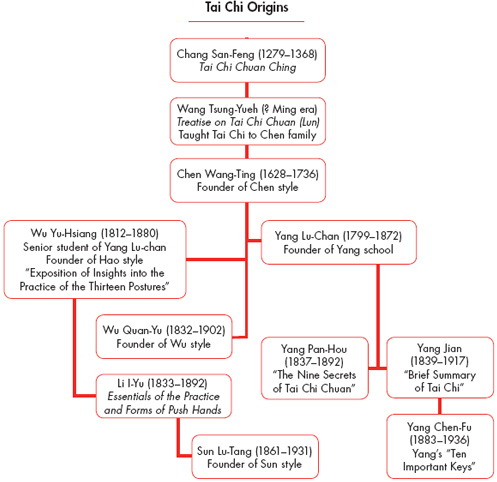

Fig. 1.7. Tai Chi founders and authors of the Tai Chi classics

Fig. 1.8. Yang Lu-Chan (1799–1872)

The Universal Healing Tao form is in part derived from the Small-Frame Fast Yang Tai Chi form and the Bird’s Tail form from the long Tai Chi form.

Yang Lu-Chan had three sons: Yang Qi (died early), Yang Pan-Hou (1837–1892), and Yang Jian (1839–1917). Yang Pan-Hou was likely the original author of “The Nine Secrets of Tai Chi Chuan,”9 and a contributor to the Yang Family Forty Chapters, which included oral transmissions from the legendary Chang San-Feng (fig. 1.9).10 This book, which will be discussed in greater detail in chapter 3, makes the important connection between “closing” and Fa Jin. Closing is the returning of the arms to the torso, which activates and expands the tan tien, providing the power for executing the discharge. Chapter 24 says, “When there is a closing (therefore storing the jin), (the jin) immediately emits.”11

Fig. 1.9. Yang Pan-Hou (1837–1892)

Yang Lu-Chan’s third son, Yang Jian, wrote the work known as the “Brief Summary of Tai Chi.” The third son of Yang Jian was Yang Chen-Fu (1883–1936), who gave the oral transmission of “Ten Important Keys to Tai Chi Chuan” and the “Explanation of Tai Chi Chuan’s Harmonious Stepping in Four Sides of Push Hands” (fig. 1.10). In the “Ten Important Keys,” he says:

Fig. 1.10. Yang Chen-Fu (1883–1936)

Taijiquan uses the Yi without using the Li. From the beginning until the end, continuous without breaking [when] complete, again repeated from the beginning, cycling without limitation. It [is] what was originally said [to be] “Like the long great river [i.e., Yangtze River], flow fluidly without ending.” It is also said: “Transporting the jin as drawing the silk.” All of this means the [movements] are threaded through [i.e., together] with a sole Qi.12

This excerpt explains some aspects of Fa Jin that are unlike the coordination that occurs in our everyday mind. Instead, Tai Chi—and in particular Fa Jin—requires the use of a deeper state of mind. This state of mind arises when the practitioner is able to relinquish control to an integrated self. This integrated self is called Yi power, and it is formed in the merging of the brain, heart, and lower tan tien. Yi power moves chi, which transports the jin. This movement of chi is a very pleasant sensation, which involves a very delicate yin approach—like drawing fine silk. Paradoxically, it is this delicate yin power that generates the overt maximal yang power.

Yang Lu-Chan taught Wu Yu-Hsiang (1812–1880), who was the author of “Exposition of Insights into the Practice of the Thirteen Postures” (fig. 1.11). This work teaches us that “to Fa Jin, sink, relax completely, and aim in one direction!” The sinking and relaxing is a vital aspect of Fa Jin. Since discharge power is generated from the realm of yin, it is important to embody yin thoroughly—to relax, contract the tan tien, tuck in the coccyx, and sink deeper into one’s structure. This gives a sensation of connecting to the earth and even to the vast realm of empty space beyond it. From that space a spark alights within the tan tien, which inflates it at maximal acceleration. Sinking and relaxing is more powerful than using muscular strength or Li power.

Fig. 1.11. Wu Yu-Hsiang (1812–1880)

Fig. 1.12. Li I-Yu (1832–1892)

Wu Yu-Hsiang taught Li I-Yu (1832–1892), who was the author of many classic works, including “Thirteen Postures,” “The Secrets of Withdraw and Release,” “Five Key Words,” “Important Keys of Stepping and Striking,” “Song of Tai Chi Chuan Applications,” “Secret of Eight Words,” “Song of Transporting and Applying Spirit and Chi,” “Song of Random Circle,” “The Acclamation of Tai Chi Sparring,” and “The Small Forward of Tai Chi Chuan” (fig. 1.12). Li I-Yu says:

To Fa Jin it is necessary to have root. The jin starts from the foot, is commanded by the waist, and manifested in the fingers and discharged through the spine and back. In the curve seek the straight, store, then discharge, then you are able to follow your hands and achieve a beneficial result. This is called borrowing force to strike the opponent or using four ounces to deflect a thousand pounds.13

In this quote we are reminded of the basics of the Universal Healing Tao system. Iron Shirt structure is the foundation that provides the rooting power. The waist, also known as the Chi Belt or Dai Mai, maintains the solid connection between the legs and the torso. As per the foundational form of Tai Chi Chi Kung, the chi is transmitted from the earth through the spine and discharged via the palms. This is done with a sense of the delicate or yin power. By following all these principles, a seemingly minute force is enough to move a large man.

BA GUA ZHANG AND FA JIN

Dong Hai-Chuan (1797–1882), the creator of Ba Gua Zhang and author of the Thirty-six Songs and Forty-eight Methods, believed that connections to the eight forces would give a practitioner access to universal power.14 This power is the same discharge power that is used by the Tai Chi masters.

At times, Dong moves from the mystical to the practical. In song nine, he refers to Fa Jin and reminds readers to “use the ‘Hen’ and ‘Ha’ sounds when releasing the power. The whole body’s energy rises.”15 Although the use of sound has not been mentioned to this point, it may be a useful adjunct in the manifestation of discharge power. Sound activates the empty force and lower tan tien, which are vital aspects in the release of discharge power.

Dong also says, “Step back to know the situation/small force can deflect much greater power.”16 He reminds us of the importance of reading the opponent correctly, and of choosing the right moment so that only a small amount of effort is required.

To continue with Dong’s classic; in chapter eight on the internal power method he says, “Power discharge is from harmony of mind and force.”17 Here he emphasizes but fails to elaborate on the importance of the mind in discharge power. Universal Tao practice teaches that with refinement, force and mind merge: the three minds become one mind. The mind moves the chi, which moves the limbs. Minimal separation exists between intention and actualization of force.

In chapter nine on the power storing method, Dong comments that storing power is just as vital, if not more important, than releasing it.18 Another way to look at this is to recognize that the tan tien needs to be full. If the tan tien is empty then the execution of discharge power is disabled. Everything is done in moderation and nothing to excess such that the lower tan tien is never depleted.

HSING YI AND FA JIN

Hsing Yi is the third internal art. It is older than Ba Gua Zhang and Tai Chi, and supposedly originated in the tenth century during the Song Dynasty. The founding of Hsing Yi is credited to General Yue Fei. Although it is labeled an internal art, Hsing Yi’s forms are more typical of an external martial art. This is because its strikes and blows are linear and aggressive. It demonstrates Fa Jin through explosive strikes rather than the throwing and uprooting of opponents as seen in Tai Chi. However, the cultivation of Fa Jin that is behind these strikes is based on internal softness, stillness, visualizations, and connections to the elements and symbolic animals. The five different types of power released are Pi, Tzuan, Beng, Pau, and Hern; they correspond to the elements of metal, water, wood, fire, and earth. The three main schools of Hsing Yi—Shanxi, Hebei, and Henan—vary in certain details, but the twelve animals generally included are: dragon, chicken, monkey, hawk, sparrow, Tai bird, eagle, bear, snake, tiger, horse, and turtle.