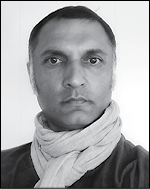

Zubin Shroff

My very first association with yoga was at my grandparents’ house in South London. Whenever I visited, the morning would begin with my grandfather practicing yoga in the living room, usually alone. If anyone else was around, he would continue undistracted. There was no special mat or outfit or elaborate ritual—to him, yoga was as ordinary as having breakfast or going to the pub in the evening. In fact, my grandfather’s daily routine was to practice yoga every morning and go to the pub every evening. He saw one of his roles as teaching me about life, so he showed me a few things about yoga to build a healthy mind and body. And in the summer when the weather was good, he would take me to the pub, which was his community. Children weren’t allowed inside, so we would sit in the garden with his friends. Yoga and the pub were both equally recurring parts of our hybrid life; in the same spirit, his other passions were his perfect English lawn and his twice-daily Zoroastrian prayers.

I started to actively practice yoga when I was around twelve in a cold, drafty house in Edinburgh. We had recently moved and my mother started taking yoga classes as an opportunity to meet new friends and get fit at the same time. I would copy her when she practiced at home, making fun of her struggles to get into poses that, with a child’s body, were easy for me. Wanting to emulate my grandfather, I continued to practice when my mother’s busy life led to her practice slipping away. Like many things in my life, I learned from my grandfather’s example, and if anything defined yoga for me, it was discipline and steadiness. Committing to this practice made me feel good, cleared my mind, and strengthened my body. It was my breath, my body, and myself. Simple, profound, and personal.

In Mumbai, my aunt and uncle and their friends had yoga classes in their homes. They studied with B. K. S. Iyengar, a popular teacher with the Mumbai Parsi community, not yet the celebrity he later became. None of them had the “yoga bodies” as understood by twenty-first–century North American yoga studios. Many of them could not touch their toes and none wore “yoga pants.”

For me, yoga was my connection to family, whether in India or England; it was something done at home by ordinary Indian men and women with a vast array of body types. There were no special yoga mats or clothes and, as my family are not Hindu, no association with Hanuman or Ganesh or Siva. There was very little presence of yoga in British popular culture at the time, so there was nothing to compare my experience of yoga with.

The Yoga Scene—Not My Scene,

New York Hybridity & Searching for a Yoga Teacher

Years later, when I got my first glimpses of North American yoga, it looked and felt very alien. I was now living in New York and had worked most of my life as a photographer. In the mid 1990s, I was asked to make some images of a popular yoga studio. I entered a room of seventy to eighty sweaty people, all white, all young—Why were they sweating so much, was the air conditioner broken? I had never seen people sweat like this doing yoga. Hindu deities adorned the room, Hindu chants played in the background, and everyone greeted me with “namaste.” The teachers running the studio were very generous and invited me to come and take a class, but it was too foreign to make any sense. I felt it had no connection with the yoga I understood, nor to any of the bodies I knew who practiced it. My aunts and uncles, my grandfather, their friends, they would have been completely out of place here.

A few years later, when I had a serious accident, yoga became a tool to regain my strength, reintegrate my broken body, and deal with the remaining weakness. Two years went by, and still asana that were once so easy were no longer possible. All that was left of my once active practice was the simplest breath work. At the same time, all around me, the yoga industry boomed, but I paid little attention to it. To me, the rise of this particular form that was North American yoga was just another unrealistic way India and Indian-ness were exoticised and disembodied from the actual country and from my own experiences.

But something brought me back to my practice. I realized that in striving for and achieving the conventional definition of success in my career, life had become overly complex, busy, boring. I craved balance and perspective, and I knew yoga was the tool that would help me find it. Now my practice was very different, more internal and less physical. I spent a year deeply immersing myself back into my yoga practice, but did not tell many people around me. It was not a secret; I just didn’t see the connection of what I was doing to this “other” yoga that was popping up all around me. This other yoga now on billboards and in magazines, being used to sell diet pills and cars with images usually depicting the same type of person increasingly separated my understanding of yoga from this new, mainstream public face.

After this intense year of self-study, when my only yoga book, Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha by Satyananda (the book my mother had originally used in the 1970s), was falling apart and bulging with post-it notes, I felt it was time to find a teacher to help me learn more. At this point, it was 2008; I still didn’t own a yoga mat and I had still never been to a yoga class. In fact, the idea of practicing yoga with a room full of strangers, whatever they looked like, seemed almost indecent.

With some research, I discovered the most available way to study intensively was to do a teacher training. To my mind, becoming a yoga teacher after 200 hours of study was so unfathomable a concept, it wasn’t even concerning. As I looked for trainings led by people I could identify with, I quickly understood that even if the teacher’s name was Shiva or Devi, they were probably not of South Asian origin, yet they may be wearing mala beads and bindis, quoting more Sanskrit words that any of my South Asian friends ever did. Put off by this, I considered enrolling in a training in India, but I never did well with Indian patriarchal authority, a learning style that was based on doing what you are told and not asking questions. I remember my family telling me how mean their Iyengar teachers had been and how Mr. Iyengar would sometimes kick people who weren’t doing poses properly; this was not what I was looking for. Nor did I recognize myself in the growing Hindu religious expressions of yoga seen in the mass popularity of teachers like Ramdev, who used his yoga camps to promote his homophobic and Hindu fundamentalist views.

I felt stuck. My life in New York was a hybrid, contemporary one with artists, academics, and activists from Brazil, India, Iraq, and the United Kingdom all learning with North America’s hyphenated and inclusive identities: Asian-American, African-American, LGBTQ, Jewish New Yorkers, all rooted in disparate traditions, creating a new hybrid one. In many ways, my own practice of yoga mirrored this—rooted in history, in family, it helped me connect with the here and now, absorbing new experiences and gaining new insight. I realized that if I were to connect with a yoga community, it would have to look the hybrid evolving one I lived in.

I did, in the end, choose a teacher training where one of the main teachers was Asian American, highly skilled and experienced, and there were a few other people of color in the class. I was planning to sit in the back, learn what I could, and go back to my own yoga practice.

Instead, I was captivated by the generosity of my teachers, Rodney Yee and Colleen Saidman, their ability to support forty other students, who in turn showed me an equal number of different ways to practice. People brought their own knowledge and experience to yoga with passion and intent. In this inclusive environment, I began to imagine the great relevance a truly diverse yoga community might have. Both yoga and South Asia have a long history of absorbing and evolving with different thoughts and cultures, all connected yet distinct. This history mirrors the vision of the United States, as a country of inclusion and experimentation, of imagining new possibilities. Perhaps yoga could help strengthen this in the face of opposing forces of isolation, alienation, and hate. I had long conversations with my fellow like-minded student (and now yoga sister) Ericka Phillips. We both imagined a radically inclusive yoga community that both reflected and helped us navigate our lives and interests.

Spiritual Bypass, Appropriation & Exclusion

At the same time, I attended other classes that made me feel I was back in 1980s London. One where a teacher, trying to help students pronounce proper Sanskrit, suggested they wobble their heads and talk with the kind of accents I had only previously heard in racist taunts and the absurd characterizations in the Carry On films of sixties and seventies Britain. Other classes taught mistellings of Hindu myths and made sweeping generalizations of Indian culture.

I felt the vibrant and complex idea that is South Asian being stripped away and replaced with an exotic and ancient Indian simulacrum used to make one feel spiritual and universal and bypass any understanding or engagement with the real world we live in. It was clear that most of my South Asian friends had a great dislike for all things being presented as yoga, my international friends largely ignored it, and those involved with social justice saw it as part of the problem.

I heard black and brown people honestly saying yoga is just for white people. The truly painful part was I could see how they could think that. I saw how the yoga taught in many mainstream studios often perpetuated beauty myths and body-shamed many who did not conform with its idealized image; how complicated poses were experienced as something you failed at rather than a tool to reveal and celebrate one’s own body; how dharma talks of “we are all one” could easily be used to ignore issues of race, gender, and sexuality that separate us and our responsibility for creating the world we live in.

Despite the increasingly problematic mainstream face, I did begin to meet people in the undercurrent—individuals and groups that were both honoring the tradition and making the practice contemporary, who saw yoga as not just a pursuit of flexibility but a way of life, as a spiritual practice that could be put into service to support just and inclusive communities. I met people who taught in halfway houses, incorporating yoga into mental health fields, teaching donation-based classes, and working with communities of color. Meeting so many committed yogis made me ask myself what my role was. What could I do to offer this practice that has been so important in my life to those who were being excluded and build a yoga community that was relevant to my life and most of the people I knew?

California: No, We Are Not All One,

Diversity, & Resistance

After I moved to the Bay Area, a chain of circumstances led to me being asked to take over the running of a well-established studio in Oakland, and I saw an opportunity. My goal was threefold: to teach yoga as a multifaceted practice that would equally include asana, meditation, pranayama, and self-discovery, to build a diverse community of both students and teachers, and to use the practice as a guide to skillful living and service.

Naively, I was surprised by the strength of resistance I encountered from the existing community. Diversity and inclusion are easier to talk about than practice. Whilst the studio had many talented teachers of asana, body mechanics, and breathing practices, I saw little if any interest in supporting self-exploration or accountability for one’s actions and the society we live in. The social structure was not welcoming to the new teachers or students I was trying to attract. The studio felt like an island isolated from the Oakland that was walking in the streets outside, and it didn’t want its sanctuary disturbed. Safe space is a popular idea in yoga studios, but what does a safe space look like? Is the aim of a safe space to protect us from facing our fears and misunderstandings or does it serve us better as a place where we are able to sit together and explore our own discomfort and responsibility—a space for honesty and for transformation? If making a space that is safe for us contributes to a lack of safety for our neighbors is this really practicing yoga?

To diversify our community, I saw it essential to bring in teachers of color, to actively invite a diverse population into our teacher trainings, and to teach in a way that they would feel included and valued. Unfortunately, the teachers of color I did attract didn’t stay, as they didn’t feel comfortable in the existing culture, and many of the increasingly diverse student body did not feel seen or heard by the predominantly white faculty.

What I thought would be a relatively easy transition turned into a multi-year battle that was confusing and isolating. I had hoped the change would be gradual and inclusive, assimilating the existing studio community with the new community I imagined, but this was not to be. The great fortune of resistance is that it can be used to clarify your vision and strengthen your resolve, and with the help of other teachers and students the path became clear. Eventually, I turned to my own community of teachers and supportive allies who have always been near in times of need. I had met Ericka Huggins a couple of years prior, when I interviewed her for a book I was working on, and I called on her for help. She understood my vision and, with her ever-present generosity, supported me unflinchingly and guided me through this difficult time, and I am constantly grateful for her support.

Finding Community in Oakland

The clarity that was revealing itself was further directed by the social climate we are living in, where more and more people are awakening to the great turmoil around us: weekly videos of police brutality, of a deeply divisive political climate, and of powerful new visions provided by activists challenge our understanding of leadership and whose voices are valued. This clarity was matched by the certainty of how relevant a spiritual practice like yoga is to help us build a culture of self-care and build the supportive and skillful communities needed to lead us into change that is loving, just, and transformational. With this clarity and purpose came the strength to make big and uncomfortable changes to the structure of the studio and the support of more and more teachers and students who had the same vision.

Today, our studio is supported by a rich, loving group of friends and allies, where we teach and learn in collective groups of students and teachers. We challenge the idea of a teacher as one with ultimate authority who passes out knowledge as they wish and, instead, we try and see that at all times knowledge and moral, ethical, and spiritual authority flows between different members of the group. We challenge ourselves with honest, and sometimes uncomfortable, conversations. In this process, many of us find healing and truth, while others feel too confronted. As I continue this work, I realize that to have an honest and transformative community, we cannot all agree and some will fall away and that has to be okay.

In this yoga community that I feel so honored to be a part of, I see that as we continue to learn how to challenge our assumptions, work with conflict, and strengthen our voices, our practice together is often difficult and imperfect and constantly evolving. I see us celebrating this with a spirit of generosity, forgiveness, and inquiry. I finally feel part of a yoga community that mirrors my world outside yoga. I finally feel my own individual yoga practice has found its home.

As director of Piedmont Yoga, Zubin oversees and informs the future direction of the studio. He teaches in the 200-hour and 300-hour teacher trainings and in the Integrative Yoga Therapy Teacher Trainings, as well as in Oakland public schools and in hospitals. Zubin is the author of Conversations with Modern Yogis, a comprehensive collection of his interviews and portraits of yoga practitioners and teachers in North America, and The Cosmopolitans, a collection of portraits exploring the meaning of cultural identity. Author photo by Zubin Shroff.