Chapter 4

The Cutting Edge: Working with Knives

IN THIS CHAPTER

Purchasing the knives you need

Purchasing the knives you need

Giving your knives the proper care and feeding

Giving your knives the proper care and feeding

Using your knives to chop, cube, slice, and more

Using your knives to chop, cube, slice, and more

Carving poultry, roast, lamb, and ham

Carving poultry, roast, lamb, and ham

This chapter is all about understanding and using the most important pieces of kitchen equipment you’ll ever own: knives. Professional chefs revere their knives the way jockeys respect horses, and those knives can last for decades. A really high-quality, super-sharp knife that feels well balanced and comfortable in your hand can practically give you kitchen superpowers. Seriously! A really great knife is one of the secrets of a really great cook.

In this chapter, we explain everything you need to know about kitchen knives, from buying and maintaining them to holding them and cutting with care. Whether you want to chop an onion, cube a potato, or carve a turkey, you find the how-tos in this chapter.

Buying Knives for All Occasions

Investing in quality knives yields dividends for years. A good chef’s knife will be your constant companion in the kitchen, although as you progress you’ll likely need several others.

Investing in the three essentials

Chef’s knife

A chef’s knife (shown in Figure 4-1) can be used for all sorts of chopping, slicing, dicing, and mincing. This knife is really the workhorse of the kitchen, so investing in a quality chef’s knife always pays off.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-1: A chef’s knife is handy for all sorts of chopping chores.

Serrated knife

Have you ever tried to slice a baguette with a regular knife? It’s not only frustrating but also dangerous. For this reason (and many others), we include a serrated knife on our list of essentials.

A serrated knife (shown in Figure 4-2) generally has an 8- to 10-inch blade, and you want to find one that has wide teeth (meaning the pointy edges along the blade aren’t too close together). This type of knife is essential for cutting bread; a chef’s knife can do the job if you’re in a pinch, but a hard-crusted bread dulls a chef’s knife quickly. A serrated knife is also handy when slicing tomatoes and other foods that have thin but resistant skins.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-2: A serrated knife is great for cutting crusty breads and tomatoes.

Paring knife

A paring knife (shown in Figure 4-3) has a blade from 2 to 4 inches long. You use it for delicate jobs like peeling apples and other fruits, trimming shallots and garlic, removing stems from strawberries, coring tomatoes, and making vegetable or fruit decorations.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-3: Use a paring knife for delicate cutting tasks.

Adding to your knife block

As your cooking skills develop, you may want to consider buying one or more of these knives as well:

- Boning knife: This one, used to separate raw meat from the bone, is generally 8 to 10 inches long and has a pointed, narrow blade.

- Fish filleting knife: With a 6- to 11-inch blade, this knife resembles a boning knife, but its blade is thin and flexible to perform delicate tasks.

- Slicer: This type of knife is mostly used to slice cooked meat. It has a long, smooth blade — 8 to 12 inches — with either a round or pointed tip.

- Cleavers: These knives feature rectangular blades and look almost like hatchets. They come in many sizes, with some cleavers heavy enough to chop through bone and others intended for chopping vegetables.

Shopping wisely

When you’re ready to go knife shopping, you need to know a thing or two about what knives are made of as well as how to compare those on the shelf.

Knowing the knife composition

Knives come in several types of materials, each of which has its advantages and disadvantages:

- High-carbon stainless steel: This material is the most popular choice for both home cooks and professionals because it combines the durability of stainless steel with the sharpening capability of carbon steel. It’s also easy to clean and doesn’t rust.

- Carbon steel: Used primarily by chefs who want an extremely sharp edge, carbon steel has the disadvantage of getting dull quickly. It also gets discolored from contact with acidic food.

- Ceramic: Made from superheated zirconium oxide, ceramic knives are denser, lighter, and sharper than steel. In fact, ceramic knives stay razor sharp for years. The main drawback is that the blades can shatter when dropped. They’re comparable in price to other knives.

Homing in on what you want

Every department store carries kitchen knives these days, and many of them look quite impressive. But not all knives are the same. Some look great but are lightweights with thin, insubstantial blades that just won’t last. How do you find knives that will still be part of your life years from now? When you’re shopping for knives, keep the following tips in mind:

-

Before you buy a knife, hold it in your hand. If the knife is well constructed, it should feel substantial and balanced for you.

Before you buy a knife, hold it in your hand. If the knife is well constructed, it should feel substantial and balanced for you. - Assess the knife handles. When shopping for large knives, like chef’s knives and cleavers, look for those with riveted handles featuring three circular bolts that provide stability.

- Consider only knives whose blades are forged. This means that the blades taper from the tip to the base of the handle.

- Look for reputable brands. Here are some to consider:

- Chef’sChoice

- Global

- Henckels

- Hoffritz

- International Cutlery

- Kyocera (ceramic knives)

- Sabatier

- Wüsthof

Caring for Your Knives

After you invest in quality knives, you want to make sure they give you peak performances for many years. The advice in this section can help.

Storing and washing

Here’s rule number one: Don’t store your good knives in the same drawer with other cutlery where they can be damaged. You don’t want your good chef’s knife getting into a wrestling match with a pizza cutter! Instead, keep your knives in a wooden knife holder or on a magnetic strip mounted on the wall (out of the reach of children).

Wash your knives with warm soap and water, using a sponge or plastic scrubber. Don’t put them in the dishwasher, and don’t scrub them with steel wool.

Also, because you want your knives to look shiny and nice, never leave acid such as lemon juice or vinegar on a knife blade; it can discolor the surface.

Sharpening twice a year

Quality knives are only as good as their sharpened cutting edges. To keep your knives in peak condition, you may want to have them professionally sharpened a couple times a year. Don’t have them sharpened more often than that because oversharpening wears down the blade. Your local butcher, gourmet retailer, or restaurant supply store may sharpen your knives or put you in touch with someone who does. You can also ask a professional chef to sharpen your knives for you.

An alternative is a home sharpening machine. You can find these devices, which start at about $40, at knife retailers. They do a fairly decent job, but they definitely don’t match the quality of professional sharpening.

You can also use a sharpening stone, which professional chefs typically use. These flat, rectangular stones, about 8 to 10 inches long, come in various types and grits. The technique: Apply one edge of the knife to the stone, moving the blade across the surface as though you’re cutting a thin slice off of it. Then do it in reverse. Stones cost from $25 and up.

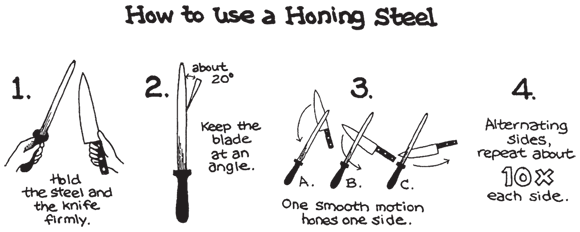

Honing before each use

To help maintain a knife’s sharp edge, you should hone its blade — move it across a sharpening steel — before every use. A sharpening steel is a long (up to 12-inch) rod of steel or ceramic with a handle. The rod has ridges on it, and when you run a knife blade across at a 20-degree angle, it removes tiny fragments that dull the edge.

Honing a knife before you use it takes less than a minute. The following steps walk you through the process and are illustrated in Figure 4-4:

- Grab a sharpening steel firmly and hold it slightly away from your body at a slight upward angle. Hold the knife firmly with the other hand. The sharpening steel doesn’t move during this process; only the knife does.

- Run the knife blade down the steel rod, toward the handle (don’t worry, it has a protective lip on the top of the handle) at about a 20-degree angle.

- Repeat Step 2, alternating sides of the blade. This may be nerve-racking at first because the technique has the knife coming at you, but with practice you’ll get the hang of it.

- Keep alternating for at least 10 times until the blade is sharp. Tip: To test for sharpness, run the blade lightly across the skin of a tomato. It should slice through effortlessly. Whatever you do, don’t test it by running your finger along the blade!

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-4: Honing a knife.

Using Knives Correctly (and Safely)

Seriously, you can avoid any knife-related accidents by following some simple rules:

- Always slice away from your hand. Notice the word slice here. If you’re using a paring knife to peel an apple, the blade is going to be facing the hand holding the apple; you can’t get away from that. But when you slice or chop or mince (all of which we explain in the next section), the blade should never be turned toward the hand holding the food.

- Keep your fingers clear of the blades. Before you say “well, duh!” consider how often we take unnecessary chances. If you’re slicing a tomato and get down to a half-inch piece remaining, what do you do? That half-inch piece is too thick to put on your sandwich, and you don’t want to waste it, so don’t you go ahead and slice it in two? Well, exactly how far away can your fingers get in this situation? Until you’re really skilled at using a knife, let the tomato go — and find some other way to use it that doesn’t require that final slice. And if you insist on making that final cut, at least use a serrated knife (which slices through tomato skins effortlessly).

- Always use a cutting board, and don’t let it slide around on the counter. Either use a cutting board with rubber feet that help the board grip the counter, or put your cutting board on a moist dish towel so it won’t slip.

- Keep your fingertips curled under when slicing. The knife should not move toward or away from the food; rather, you nudge the food toward the blade. This way, if you do misfire, you’re more likely to hit a hard knuckle than a soft fingertip.

So how exactly do you hold and move the knife? That depends on what you’re cutting and how you want the finished product to look. Keep reading to find out more.

Chopping, Mincing, Julienning, and More

In this section, we define the terms you’re most likely to see in a recipe that calls for you to prepare vegetables, fruits, herbs, and meats. We explain how to chop, mince, cube (or dice), julienne, and slice.

Chopping and mincing

Chopping food means to use your chef’s knife to cut it into pieces. Those pieces don’t have to be exactly uniform, but the recipe will often tell you whether you need to chop something finely, coarsely, or somewhere in between. Another word for chopping something very finely is mincing. You’re most often asked to chop or mince veggies or herbs.

To chop or mince, hold the knife handle in a comfortable manner and cut the food into thin strips. Then cut the strips crosswise (as thickly as desired), rocking the blade with your hand and applying pressure on top. Your best bet is to grip the handle with one hand and place your other hand on top of the blade.

Practicing on an onion

Want to practice chopping? Many recipes call for chopped onions, so they’re a good place to start. Follow these steps, which are shown in Figure 4-5:

-

Chop off the stem, and then cut the onion in half lengthwise through the bulbous center and peel back the papery skin.

Leave the root end intact. As you slice through the onion, the intact root end holds the onion half together while you slice and chop.

- Place each half cut-side down and, with your knife tip just in front of the root end, slice the onion lengthwise in parallel cuts, leaving ⅛ to ¼ inch between the slices.

- Make several horizontal cuts of desired thickness, parallel to the board.

- Cut through the onion crosswise, making pieces as thick as desired.

- Finally, cut through the root end and discard.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-5: Chopping an onion.

At www.dummies.com/go/choppingonion, you can find a video that shows you what we’ve just described.

Mincing garlic

Mincing garlic simply means chopping it very finely. In this section, we explain how.

First, a quick explanation of terms: In your grocery store, you find garlic bulbs. (Buy garlic that feels firm and hard, not soft.) A bulb is covered by papery skin. When you peel it off, you discover that the bulb contains multiple cloves with thin skins. If you have difficulty removing individual cloves, take a butter knife and pry them out. Then, here’s what you do:

-

Peel the cloves.

To help you get the skin off easily, set the cloves on your cutting board, and lay your chef’s knife across them with the blade facing away from you. Hold the knife handle with one hand, and use your other hand to whack the side of the blade above the cloves. Doing so should break the skins and let you slip them off easily.

-

Hold the garlic clove on the cutting board, with the knuckles of your index finger and middle finger leaning against the side of the knife blade.

Keep your fingertips folded inward to prevent cutting yourself.

-

Keeping the tip of your knife on the cutting board, pump the handle up and down while you move the clove under the blade.

You’ve probably seen this technique used by the pros on cooking shows.

- Slowly move your knuckles toward the other end of the garlic as you mince.

Using fresh garlic really is worth a couple extra minutes of prep time because the flavor is so superior to the stuff that comes pre-chopped in a jar. That ingredient works in a pinch, however, so it doesn’t hurt to keep a jar in the refrigerator.

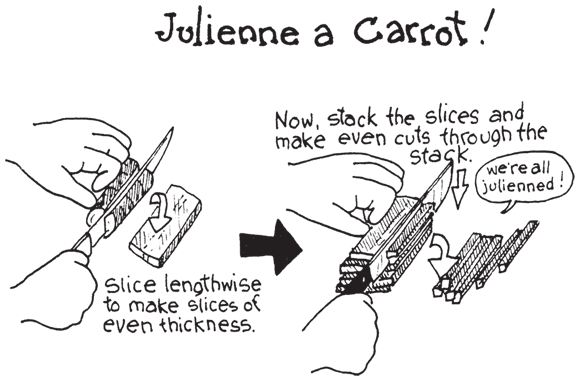

Julienning

Don’t let the French accent scare you: Julienned vegetables are as simple as they are attractive. Just trim a vegetable, like a radish or carrot, so it’s flat on all sides. Slice it lengthwise into ⅛-inch thick pieces. Stack the pieces, and slice them into strips of the same width. See Figure 4-6 for an illustration of this technique and visit www.dummies.com/go/juliennecarrots to watch a chef in action.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-6: Julienning a carrot.

Cubing (or dicing)

If you can julienne vegetables, cubing is a breeze. Think of a potato. Trim all the sides until it’s flat all around. Cutting lengthwise, slice off ½-inch-thick pieces (or whatever thickness you desire). Stack all or some of the flat pieces and cut them vertically into even strips. Cut them crosswise into even cubes.

Dicing is the same as cubing, except that your pieces are smaller: ⅛ to ¼ inch, usually.

Halving tough-skinned vegetables

With their nearly impervious skins and odd shapes, winter squash, such as butternut squash, is difficult to cut open. We recommend using a Chinese cleaver and a mallet or hammer rather than a chef’s knife, which can slip. The squash will be fresher and cheaper if you cut and peel it yourself. But for convenience’s sake, many markets now sell precut butternut squash. Follow these steps, which are shown in Figure 4-7:

-

Place the squash on a cutting board.

If needed, place a damp kitchen towel underneath the cutting board to help stabilize it.

- Place the cleaver on the squash so its blade runs lengthwise from stem to end.

- To make your first cut, hit the top of the blade with the mallet, pounding several times until the cleaver completely severs the squash in half.

- Using an ice-cream scoop or a large spoon, remove and then discard all the seeds and fibers.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-7: A safe and easy way to cut a winter squash.

Slicing

Slicing is the most common — and most important — knife task. There are really only two things to keep in mind:

- If you’re slicing a hard, round vegetable, like an onion or a winter squash, trim one side flat first so it doesn’t roll around on the cutting board.

- Take your time to assure evenly thick pieces, whether you’re slicing an onion or a pineapple. Doing so makes the food look better and cook more evenly.

Figure 4-8 shows how to slice a scallion. As you can see, you can slice with the knife straight in front of you or at a slight angle with the blade moving away from you.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-8: Slicing a scallion.

Paring

Paring is one of the only cutting tasks you perform while holding the ingredient in your hand. Don’t worry — you don’t need the first-aid kit nearby! Your hands are designed for this kind of work. Paring means to remove skin from fruits and vegetables as well as to sculpt them into decorative shapes. They can be small items, like shallots and garlic, or larger ones, like apples and tomatoes. Above all, a paring knife must be razor sharp to perform well.

To pare an apple, for example, hold it in one hand, barely pressing it into your palm, with fingers bracing the surface (outside of where the cutting proceeds). Pierce the skin of the apple with the paring knife and carefully peel it toward you, slowly turning the apple with your thumb. Spiral all the way to the bottom (see Figure 4-9). Although fruits and vegetables come in different shapes, this technique of holding food and slicing toward you is the same. Need a visual to help you figure out the best way to pare? Be sure to check out www.dummies.com/go/paring.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-9: Go round and round when paring an apple.

Carving Poultry and Meats

If you’re daring enough to cook a whole chicken, turkey, roast, leg of lamb, or ham (all of which we show you how to do later in this book), you’re definitely up to cutting your masterpiece in preparation for serving it. We offer illustrated instructions in this section, and you can find videos at www.dummies.com/go/cooking that put these steps into action.

Showing a turkey or chicken who’s boss

If the thought of carving your Thanksgiving masterpiece or even your Sunday dinner staple gives you the chills, we’re here to help. Because chickens and turkeys are anatomically similar, this technique works for both. Here are the steps to follow, which are illustrated in Figure 4-10:

- Place the chicken or turkey, breast-side up, on a carving board.

-

Remove one leg by slicing through it where it meets the breast.

Pull the leg away from the body, cut through the skin between the leg and body, and then cut through the joint.

-

Separate the drumstick from the thigh.

On a cutting board, place the drumstick and thigh skin-side down. Look for a strip of yellow fat at the center. That’s the joint. Cut through the joint.

-

Remove the wing on the same side of the bird.

Cut as close to the breast as possible, through the joint that attaches the wing to the body.

-

Carve the breast meat.

Hold your knife parallel to the center bone and begin slicing halfway up the breast. Keep the slices as thin as possible. Continue slicing parallel to the center bone, starting a little higher with each slice.

- Repeat the whole process on the other side.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-10: Carving a chicken or turkey.

Cutting a pot roast

When it comes to serving a pot roast, you need to follow one simple rule: Cut it against the grain so the meat holds together and doesn’t shred. Figure 4-11 shows how to do it, as does www.dummies.com/go/carvingroast.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-11: Cut across the grain to avoid shredding the meat.

Slicing a leg of lamb

You may not make lamb as often as you do poultry, but won’t your family or guests be impressed when you show off your expert carving skills! Figure 4-12 illustrates how to properly carve a leg of lamb. A chef’s knife is best for this task, although you may use a boning knife for hard-to-get pieces.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-12: The proper technique for carving a leg of lamb.

Handling a ham

When you prepare a gorgeous ham (see Chapter 8 for a delicious recipe), you want to be sure to serve it thinly sliced rather than chopped into chunks. You can use a chef’s knife or a serrated knife. Figure 4-13 offers a ham-carving primer as does the video at www.dummies.com/go/carvingham.

Illustration by Elizabeth Kurtzman

FIGURE 4-13: How to carve a ham.

Most home cooks can get along with three versatile knives: a 10- to 12-inch chef’s knife, an 8- to 10-inch serrated (bread) knife, and a small paring knife.

Most home cooks can get along with three versatile knives: a 10- to 12-inch chef’s knife, an 8- to 10-inch serrated (bread) knife, and a small paring knife. Many knife injuries are the result of rushed, hungry people doing dumb stuff, like trying to separate frozen hamburgers or slicing through hard bagels. So rule number one is, don’t do dumb stuff! (Or maybe it should be, don’t use knives when you’re starving!)

Many knife injuries are the result of rushed, hungry people doing dumb stuff, like trying to separate frozen hamburgers or slicing through hard bagels. So rule number one is, don’t do dumb stuff! (Or maybe it should be, don’t use knives when you’re starving!)