“The story of Danny O’Neill. The End,” Sammael wrote, then closed the Book of Storms.

“Right,” he said to Kalia. “Home time, I think.”

Kalia was lying down, waiting for him. She didn’t move.

“Kalia!” Sammael snapped his fingers.

The lurcher whimpered.

“Come on,” he said. “We need to get on back.”

“I’m caught,” said the lurcher in a voice so faint that even Sammael could barely hear it.

“Caught? How caught?”

“I don’t know.… It’s wire or something, and then the horse trod on me.… It hurts.…”

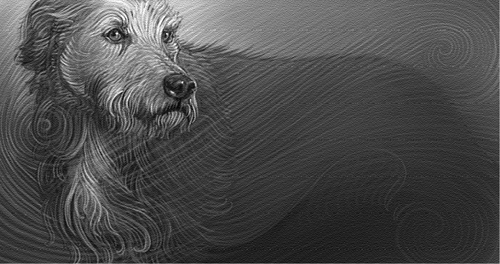

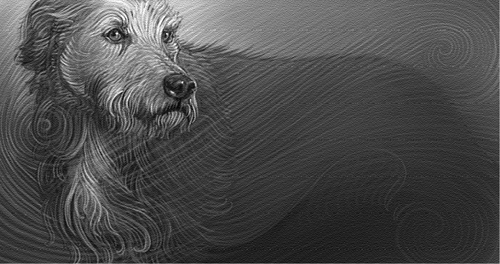

Sammael chucked the book down and crouched by the dog’s long body, feeling it with his hands. She was lying flat—her head, shoulders, and ribs were all fine. Then, as he reached her hind legs, he encountered a sticky mass. She was caught in the wire of a rabbit snare.

“Leave me,” she said. “I’m dying—there’s nothing you can do. Leave me.”

Sammael’s jaw clenched. The dog hadn’t asked for eternal life. All she’d asked was to be his dog and for him to be her master. That was the only bargain they’d ever made. Her paw print was in his notebook as a witness to it. He owed her nothing, could demand her safety from no one.

Her skull under his palm was narrow and frail.

“You stupid, idiot animal,” he said. “Why didn’t you make me give you a long life?”

“But then I’d have known how long I had with you,” said Kalia. “I’d have known when it was going to end. It would have broken my heart.”

“Better your stupid heart than your legs,” said Sammael.

“No,” whispered Kalia. “My legs are mine to break. But my heart—that’s yours.…”

She fell into a faint, her eye closing. Sammael put a hand on her ribs: still something beating in there. Still a pulse. She was shivering faintly. He shrugged his bony shoulders out of the sleeves of his coat and laid it on top of her. Only two creatures had inhabited that coat—its original owner and himself. Neither had belonged to the solid earth. Could the coat’s mysterious power do anything for a dog?

He felt for the wire of the snare again. Slowly, with infinite patience, he began to untwist it, trying not to hurt her further.

* * *

Shimny lay on the slope, not caring to check how many of her legs were broken. She couldn’t breathe, at any rate, so soon it wouldn’t matter. The end would be quick enough.

She looked up at the moon, unaware that little by little the air was seeping back into her winded lungs. She wondered why she could still see when she ought to be dead. Perhaps death slows time, she thought. For death was surely coming. She felt it in the unsettled throb of the night air, heard it whispering out from the lumps of flesh and bone that had once held both her own and Danny’s heartbeats. This short interlude was probably just a last gift to her from the living world, a last chance to taste its sharpness and feel its strong warmth.

Out of the corner of her eye she saw a woman approaching up the slope of the quarry. The woman must have seen her, but as she drew closer she didn’t hurry, her short legs dragging a little as if she was used to taking her time.

The woman crouched and put out a hand to touch Shimny’s neck just behind the ears. Her hair was white, and she had a steady, sad face.

She smiled and took her hand away.

“You’re not mine,” she said. “Not yet.”

Then she rose to her feet and made her way over to the corpse of the boy, whose neck was twisted back at an angle. The woman stooped, spreading out her arms to gather his body up and cradle him. Her hands were under Danny’s knees and shoulders when she cast her eyes down to his face, and then she stopped.

For a full minute she didn’t move but stared into his lifeless eyes, then she began to slide her arms out from underneath him.

“I won’t do it,” Shimny heard the woman say. “I won’t be a pawn in Sammael’s Machiavellian little spats. How did he do this?”

And the whispering shadows began to creep from the rocks, curling up around Death’s neck and ears. Lying in a land between death and life, Shimny’s walleye saw them too—to her they were black and green and the darkest shade of purple, half spreading into leaves as they flattened themselves out with explanations.

* * *

Death listened. When the shadows finally died away, she stood up straight and looked down at the boy’s corpse. She was bound to take it—too much of him had been lost already, pulled away into the Book of Storms.

For a moment she clenched her fist, preparing herself. Wishing, not for the first time, that she could kick a stone or punch the ground or scream any one of the millions of screams she’d been saving up since the dawn of life. But Death’s job was not to scream. It was to tidy.

Then she caught sight of the horse again, looking at her. That horse—it had seen her. It had seen her shadows. There would never be anything tidy about that horse now—it would spend the rest of its life telling crazy stories about Death and her red eyes to anyhorse who would listen. Sometimes things couldn’t be tidy, no matter how hard you tried. And sometimes they shouldn’t be.

Death walked away from the dead boy, her hand still clenched into a fist, heading for the top of the slope.

* * *

When she returned, she was carrying a small black book. Shimny had seen it before—it was the book that Danny had found in that wooden hut. Death didn’t seem to like it much: she sat down on a rock beside Danny and began tearing the pages out, cracking the spine and yanking at the stitching with her teeth. As the pages fell, she crumpled them up, sandwiching them between her knees.

She caught sight of Shimny watching her. “He was seeing to his dog,” she said, a touch defensive. “He’d just chucked it on the ground. Didn’t notice me taking it. Finders keepers, isn’t it?”

Shimny blinked.

“I’m not going to spend my time cleaning up Sammael’s corpses,” said Death. “I’m part of the natural order of things. It’s time he learned that. He might be natural, but he certainly isn’t order. Let’s see what he says to this, eh?”

With this, she tore the last few pages from the cover and reached out for Danny’s limp head. She took his face in her hands, opened his mouth, and began stuffing the crumpled pages, one by one, inside it. Even after she’d pushed a good handful inside, more than ought to have fit into a human’s mouth, she kept on going. When the pages threatened to spill out from between Danny’s teeth, she began to pack them more tightly, pushing them down into his throat with her bony fingers.

“It’s a question, isn’t it?” Death said to Shimny as she twisted up the last few pages and crushed them after the others. “Can you eat your words? Does it make any difference if you do? What if someone else eats them for you?”

Shimny had no idea what the mad silver-haired woman was talking about. But she did know that, although paper might find its way through Danny’s guts eventually, there was no way he could eat those stiff black covers from the outside of the book. She eyed them.

Death smiled at her. “Don’t worry,” she said. “I wouldn’t even put these on a dung heap. Poisonous things.” And she tucked them away inside her waistcoat.

She crouched over Danny for a moment, kissed the boy’s forehead, and then, with a grin, stood back up and dusted off her hands.

“That’ll really needle him,” she remarked to Shimny as she set off the way she had come. “Might make him think for a couple of minutes next time.”

She said this as if she didn’t really have much hope of it, but her walk as she departed had a slightly cocky jaunt. Shimny would have sworn to herself, had she not been dazed and broken, that as she watched the receding back, a slight breeze picked up toward her and she heard the figure of Death whistle.

Don’t go, Shimny found herself thinking. Please don’t go. Turn around and come back to me.

There was definitely a tune coming from somewhere—it drifted sweetly into her ears, soothing her. But it must have been Death who was carrying the tune—the notes became fainter with every moment. Pain began to bite at Shimny’s body with sharper teeth, and she closed her eyes again. What I’d like more than anything, she thought, is to keep hearing that tune.

As soon as she had enough strength, she resolved, she would scramble to her feet and follow it.

* * *

“Danny, Danny, why are you lying here? Danny! Danny!”

Danny swam from oak green gloom up toward where the light seemed strongest. The weeds were holding his feet down, tugging at his ankles to keep him anchored to the bottom. He wanted to break the surface. Although he could breathe, this wasn’t his world, where creatures that weren’t fish swam and pond weed oozed along the plush silt. It was safe, but too dark for him; the water was thick with tiny particles, and only a few strands of light penetrated down, so he could hardly see.

The world of the dead is a pond, he was surprised to find as he rose higher. But there was nobody here that he recognized: no old man, no horse. Perhaps they were the shapes of the swimming things that weren’t fish. Perhaps that’s what he was now too.

But no—he still had feet and ankles like a boy. He wrenched them free of the weeds and felt the air in his body lift him up to the light. There was a voice calling him.

“Danny, what are you doing? Get up, get up!”

The voice was pulling him toward the sun. It wasn’t the sun speaking, though—from its pure, silver tone Danny knew that it must be Death herself, watching over him. Was she calling him to join her? No—she was whistling to him. Notes glided through the water and coiled themselves softly around his ears. His chest began to warm, repelling the cold depths.

For one final second he felt regret at leaving this womblike place, and then, as the light grew nearer, he saw that it was shining and golden and stabbed straight into his heart. He was powerless to do anything but close his eyes against the screaming, stinging pain as his head broke the surface of the pond and he was thrust back once more into the world of the living.

* * *

He was lying on a shelf of rock. Above him, low black rain clouds trundled across the night sky. The rock was cool underneath his head but sharp in places; an uncomfortable lump was digging into his left shoulder blade. His mouth was choked with something soggy: he tried to gather up enough saliva to spit it out but swallowed instead. Whatever it was went down easily, as if it hadn’t been made of anything particularly solid. Perhaps it was just a bit of blood from a cut in his mouth—it had that same metallic taste.

He wriggled to relieve the pain in his shoulder and stopped in surprise. Because once he’d dislodged the lump, nothing much hurt. He ought to hurt, surely? Whatever he was doing lying here, he must have fallen somehow—he was halfway down a vast slope that stretched away, both above and below, farther than the darkness allowed him to see.

He’d fallen. Yes, that was it. He’d fallen, together with Shimny, a tangle of legs and snakes and flailing hooves. He’d been galloping away from somewhere—someone—but who was it?

The moon slid out from behind a cloud.

Sammael. Sammael had tricked him. He’d been running from Sammael, and Sammael knew where his parents were.

Danny scrambled to his feet. How did he feel so unbruised, so strong? No matter—he had to get back up to the top of the hill while there was a chance Sammael might still be there.

Where was Shimny? There—lying a few feet away. The ledge was wider than he’d thought—it must be some kind of path, winding its way up the rock face. But it would take too long to follow it. He’d have to scramble up the slope the direct way.

Could Shimny do that? Was she even alive?

“Shimny! Shimny!” He pushed his hand into his pocket and yelled silently at her. She didn’t move.

“Shimny!” he tried again. “I’ve got to go back up. Now! Meet me up there—there’s a kind of path, I think. But I’ve got to go!”

He should have touched her, but he didn’t want to, just in case she was cold under his hand. She couldn’t be dead, not Shimny, not after everything. Enough death had happened already. She would come after him as soon as she got her breath back.

He put his hands to the rock face and leaned forward against it. It was too steep to try walking, so he crawled. His knees sank onto sharp ridges, his shins scraped along jagged outcrops of blasted stone. His palms were soon ripped; as the clouds rolled away and moonlight began to let him see where he was going, he saw that he was leaving spots of dark blood glistening on the scree.

But the top was ahead of him. The wind had dropped, the rain and hail had fled. The ridge stood out black against a sky finally shining with moonlight. It wasn’t too far for him to scramble now. It couldn’t be too far.

He put his hand on a clump of spines and forced himself just in time to bite down hard on his lip and squash the yell of pain. When his knee came down in the same place, even his double layer of pajama and school trousers couldn’t protect him. It was like crawling across a lake of broken glass.

But other people did that, didn’t they? They sat on beds of nails and walked across burning coconut shells, and they still kept going. They took themselves away in their minds to other places and tried to imagine that the pain they were feeling was a good sensation instead of a terrible one. What if he could do that too? What if he could turn the world on its head and convince himself that it was his parents at the top of this slope, his parents and his own home, instead of the frightening, hard figure of Sammael?

What if Tom was up there, waiting with his strong arms to help Danny, having already vanquished Sammael? Tom would be laughing fit to bust, watching him crawl so slowly up this slope. No, Tom would come down and carry him.

So he imagined arms around him—his parents’ arms, Tom’s arms—carrying him forward and upward, and he imagined that at the top of the slope, they were all there, lined up and waiting for him.

He put his head down and crawled.

* * *

And then there it was, the ridge, so close that he could almost reach out and touch it, and there was the gap in the fence, and he was crawling along soft, springy grass again, so gentle under his knees that it felt like he was sliding along a silk mattress.

There was no need to crawl anymore. He got to his feet and ran along the fence line, keeping low like a monkey. But the fence was no cover at all—he’d be seen a mile off now, with the moonlight so bright. He made for the trees and kept to the shadows, amazed at the silence of his own feet. Something must be helping him—he wasn’t breaking twigs as he ran or treading on crunching shrubs. He could hear nothing of himself except his own breathing, which he tried to keep as slow and light as possible.

His foot nudged something hard on the ground. He’d have thought it was a tree root and run over it, if it hadn’t moved just a fraction when he kicked it.

Tom’s pitchfork! This must be the place where Apple had thrown in the towel and Tom had dropped the pitchfork as he tried to cling on.

Danny picked it up. Sammael wouldn’t be fought off with a pitchfork, he was sure of that, but the feel of the solid handle gave him heart. He wrapped both hands around it, not caring that the old wood was rough and splintery. What were a few tiny splinters after that scree?

He could try and run Sammael through with it, although who knew what might happen? Would it just go right into him and out the other side, as if he were a ghost?

There was only one way to find out: to do it and face whatever happened afterward.

* * *

He almost didn’t see Sammael. The huddled lump, still crouched over the dog, was lower than Danny had expected. But the moonlight flashed, and there he was, absorbed in his task.

Danny couldn’t see what he was doing, but he knew that waiting would mean he would miss whatever small opportunity he had. So he gripped the handle of the pitchfork and charged.

Sammael looked up at the rush. In a second he stepped over the lump on the ground and threw the entire contents of his pockets at Danny: a hail of acorns, twigs, beechnuts, and dried-out fragments of wood hit Danny’s face and bounced back onto the earth between them.

Lightning began to fall in a great, white sheet. Danny saw the first spears and threw the pitchfork before any could catch him. Eyes closed, hair standing on end, he heaved it forward with nothing more in his arm than blind hope.

The pitchfork glanced off Sammael’s shoulder and pierced the dark bundle on the earth behind him. Danny leapt onto the handle, driving it into the ground. Of course! The coat! Sammael’s power lay in his coat—if he could only keep that coat pinned down—but was the coat made of air too? Would it just disappear from the prongs of the pitchfork?

Sammael began screaming up to the storm.

“Strike the boy! Strike him down! I COMMAND YOU!”

But the lightning wouldn’t touch Danny. It crackled into every blade of grass at his feet, it set fire to the trees, it made the metal fence blaze and spark, but it wouldn’t touch him.

“STRIKE HIM!” yelled Sammael, his face burning with black fire.

And the lightning, confused, struck the pitchfork.

Danny was thrown back as the pitchfork burst into flames. He staggered and tried to keep his feet but ended up flat on the ground a few yards away, looking up at the flashing, howling sky. Rain poured onto his face.

He lifted his head to see what had happened to Sammael, but the night was too black to make out anything, now that the moon had again been covered by storm clouds. As fast as he wiped the rain from his eyes, water ran back into them again, blurring his vision.

The lightning had stopped. Nothing could control the storm, nothing could command it to fight. It had raged for only a few turbulent seconds and then blown gently over. Whatever power had called it together, the various parts of the storm had clearly been reluctant to come.

Those bits of wood Sammael had thrown at Danny—had he emptied his pocket of taros and left himself unprotected against the lightning? Had he died on that pile of flame?

No—that wasn’t possible. Sammael wasn’t made of flesh and bone, to burn away. Danny rolled over onto his stomach and crawled in the direction he thought he’d come from. His knees smarted, and his hands bled again.

He tried to play that last vision over in his mind. There had been a lump on the ground—he couldn’t be sure, but it might have been that great, thin dog. Had he driven the pitchfork into the dog, too? He hoped not.

Then the lightning had struck and dazzled him, and he hadn’t seen any more. But there was still one thing that should have been lying on the ground somewhere, that he couldn’t account for. What had happened to it?

“Lost something?” said a voice.

The schoolbag came crashing down on Danny’s head, pitching him forward. He got a mouthful of charred scrub and paddled his hands around, feeling for the bag. It wasn’t there. Sammael hadn’t dropped it on Danny’s head, he’d just swung it, to vent his anger.

He was standing in his shirtsleeves, pearl against the black sky.

“You killed my dog,” he said. “Well done.”

“You’ve lost your coat,” said Danny, pushing himself up and spitting out burnt mud. Without the coat, Sammael looked strangely thin and ordinary.

“I said, you killed my dog,” repeated Sammael.

Danny tried to swallow the spiny lump in his chest. “Yeah? Well, you tried to kill me and you tricked me and you said you’d kill my parents!”

“She was only a dog,” said Sammael. “She never did anything to you.”

“So? You should have looked after her better, shouldn’t you? What are you going to do to me now? Try and make more lightning strike me?”

“You know I couldn’t, without my coat,” said Sammael, frowning. He looked around his feet for a moment and then swiveled his eyes back to Danny. The boy was up on his knees, his face smeared with grime.

“Ha! So the river was right! You’ve lost your coat and you can’t do anything! You can’t call up storms, you can’t make them do what you want, and you can’t use them to kill people! You can’t even do anything to me anymore!”

* * *

Sammael considered the black ground, the burnt spread of ashes where his coat and his great gray dog had been. He looked at Danny once more. The boy’s face was the color of old paper—the exact shade of the Book of Storms’ stiff pages.

So that was what had happened. Sammael dropped the schoolbag at Danny’s feet and took a step backwards. He reached deep into his trouser pocket and pulled out a scant few grains of dirt. Before Danny knew what was happening, Sammael raised his hand to his lips and blew the dirt into the boy’s face.

* * *

Danny closed his eyes, expecting to be blinded, or at least to feel some stinging grit against his cheeks. But nothing happened, on the outside.

Inside, his brain warmed, as though he had pulled on a woolly hat. He thought about marzipan, thick and sweet, sitting like a blanket on top of Christmas cake. He thought about tiny lights sparkling off the waves of the sea, and the sea foam curling around itself in great tumbling streams. He thought, What if I took up surfing, and pictured those waves as exactly, as clearly, as this—I would sit on top of each wave as though it were made of thick marzipan; I would slide along it as though the wave itself were my surfboard. I could do it—I would know how to do it—if I could hold these thoughts in my head. I could learn to sit on the waves, to let them carry me across oceans—

He opened his eyes.

“Coats aren’t everything,” Sammael said softly. “And neither are storms. There are always other ways. The river didn’t tell you that, did it? But I did. You just didn’t want to listen to me.”

And he disappeared into the darkness.

Danny blinked once or twice as the thoughts of oceans drained away. Had he really just stopped Sammael building up a great storm to destroy all the world’s people? It didn’t seem possible. Not Danny, alone there on a hilltop, armed only with a pitchfork.

But was that sand Sammael had blown in his face? Was that what it did?

He was still trying to puzzle this out, turning the stick over in his hands, feeling its smoothness, when the rain dwindled away to a mist. Two tiny birds flew out of the darkness, toward him.

“It’s coming! It’s coming!”

What? Not another storm … but of course. He had summoned one himself, another lifetime ago. The storm that carried his parents.

Above him, the clouds groaned and grumbled. One gave a bellowing yawn. There was a long, satisfied burp, and the sky began to creak and mutter. Danny waited while winds trailed and zoomed around his ears, while specks of rain danced over his skin and cold plucked at his ankles. For long minutes he waited, ignoring his shivers. If only night were shorter. If only dawn would come. At least then he’d be able to see what was approaching, instead of having to stand here on the hilltop listening to the air swirling around him and trying to work out what was going to arrive first, from which direction, and at what speed.

He felt it before he heard it. If only Tom could see him now. Tom, who always prided himself on being able to predict the weather, who’d stick his head outside in the morning and say things like, “Bit of drizzle, but it’ll soon clear up,” or “This one’s set in for the day.” What would he have said if he’d seen Danny sniffing the wind and Danny had turned to him and said, “This one’s a whirlwind, just wait and see”?

Tom wouldn’t have believed it. But then he’d have heard, as Danny now heard, a peculiar stillness and a faint whistling sound. And he’d have been forced to admit, as the wind started raking him horizontally from left to right, that Danny was correct.

Because the whirlwind was upon him almost before he could steady himself. It swept him sideways, pushed him flat to a tree trunk, and pummeled at his clothes. He clutched tight to a branch with one hand and the stick with the other and began the song again. This time he shouted it, for all he was worth, until his lungs were dry and burning and his breath had been completely sucked away.

“The world is deadly, the world is bright,

The creatures that use it are blinded by sight,

But there’s no sense in crying or closing the page,

Sense only battles in fighting and rage.

So come all you soldiers and answer my call,

Together we gather, together we fall!”

And when he’d finished, instead of repeating it and waiting for an answer, he opened his mouth as wide as it would go and screamed, “STOP! PLEASE!”

The winds dropped like withered petals to the ground. There was a soft thud nearby, then another. Still blind in the darkness, Danny stumbled toward them, his hands outstretched.

“Mum?” he said, not daring to hope. “Mum? Dad?”

There was a silence longer than any piece of real time. And then a voice.

“Danny?”

It was his dad.

And then, “Danny?”

Which was his mum.

“Where are you?” he called, but they were closer than he’d thought, and a figure, clambering up off the ground, reached out to him.

He fell at it, hugging his mum tighter than he’d ever hugged before, and then his dad wrapped his arms around them both.

“Oh, Anna,” Danny’s dad said. “Oh, Danny, how did you find us?”

Danny couldn’t speak. His stomach was so full of heat and fear and coats, of swallows and lightning and the belching of clouds, that he thought he might be sick. He looked up at his parents. Even through the dark, he could see that their clothes were torn and their faces gray and exhausted. His mum’s hair stuck out like the fur on an angry cat.

“Why do you go?” he said. “Why do you leave me?”

They looked at each other. “There are things…” said his dad.

“Oh, just tell him,” said his mum, suddenly sounding like it hurt her to speak. She put a hand up to rub her eyes.

“Not here,” said his dad. “Let’s get home first.”

Danny knew they were trying not to mention his sister. But that wasn’t right—she ought to have a name. She ought to be spoken about.

“I know how Emma died,” he said. “I found your notebook. I read about Emma and the storms and all that stuff.”

He saw them flinch when he said her name, as though they’d both trodden on something sharp. Neither of them spoke for a moment, and then his mum said, “It’s very difficult, Danny. You’re … too young. You’ll understand when you’re older.”

He was about to say that he understood now, but his dad broke in.

“It was the storms, okay?” he said. “Sunday night, we both woke up and we’d had this weird dream, both of us—the same dream. She—Emma—was there, and she was talking about … about…”

His dad didn’t seem able to speak for a long moment, and then he coughed and forced out some words again.

“She was talking about storms. And she said, these days, there’re more and more of them, everyone knows that. And she said she knew why, and if we followed her, she’d tell us. So we followed her. Not her, you know, just … the thought of her. And then we were dragged up in that twister, just spinning and spinning … and we couldn’t get back down. I thought we were done for.… We just spun and spun and spun and tried to hold hands so we wouldn’t lose each other.…”

They trembled and reached out to each other again, reminding themselves that they were safe again, standing on the cold earth together. For a second Danny felt them swaying just out of his reach.

His dad said again, “How did you find us? Did you come out here alone?”

“I came with Tom,” he said. “Tom knew the way. We rode horses.”

“Tom? Your cousin Tom?”

Danny tried to see his dad’s face in the night. The moon broke free from the clouds again, and there he was, the same, familiar Dad.

“Yeah,” he said.

“Where is he now? He didn’t leave you alone up here, did he?”

He did leave me, Danny wanted to say. He left me his pitchfork. If it hadn’t been for Tom, I’d be dead by now.

“His horse ran away,” he said. “I think it just went mad. He couldn’t help it. But he must be around here somewhere.”

His mum opened her mouth, about to say something, then changed her mind and gazed at Danny. She seemed shorter, somehow. They both did. And instead of looking away from him, at his dad, Mum just swallowed and said, “Okay. Where do you think he’s gone?”

Good question. Because the storm had died away, and Tom should have gotten control of Apple and ridden her back by now. That’s definitely what he would have done, if he’d been able to.

But as the moonlight spread over the hilltop, he saw very clearly that it was just the three of them up there, and nobody else was anywhere near.