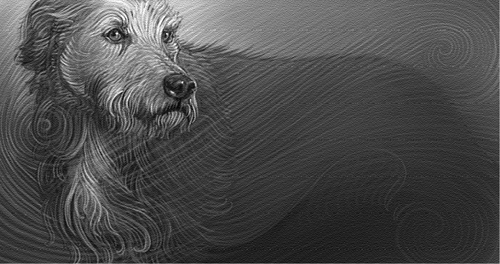

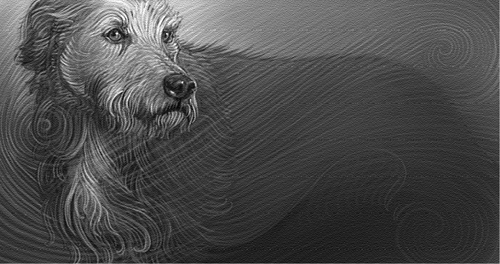

The gray lurcher put her head between her front paws and waited. Sometimes there was nothing else to do. The room was dark, her coat did little to protect her from the biting cold, and the air stank of ripe decay.

She’d have watched the clock, but her master didn’t hold with clocks. What was the point of time to someone like him?

The crackling of breaking twigs stirred the dog into raising her head. A heavy tread—he had brought someone back with him, then. These days he normally did. And even though he could have kept his journey short and neat, could have spun back into this bitter room with a flick of his wrist, he still preferred walking as much as possible. He said it gave him time to see what life was up to.

The lurcher was ready and standing by the time he ducked through the doorway.

“Another one gone, Kalia,” he said, and slung the corpse onto the floor in front of her.

Kalia sniffed at it and wrinkled her muzzle. She was well used to corpses by now, but this one was a young girl, smooth skinned and frail with a stretched face as though she’d struggled in the last minutes of her life.

“Don’t turn your nose up, mutt,” said Sammael, taking off his long coat.

As he turned to hang it on a peg, the lurcher glanced up at him. When he wore the coat, he could get away with walking among humans—he almost looked like one, if a little too tall and thin, with eyes a fraction too black. But now that he’d taken it off, she could see that his arms were narrow as broomsticks, his shoulders as sharp as wings, and his skin paler than ice.

“And don’t stare at me,” said Sammael, turning back to the corpse.

“I’m not staring,” said the dog. “It’s what my eyes look like when they’re looking. Oh, but you’ve been gone so long, I missed you. Why wouldn’t you let me come?”

“Some things aren’t for dogs,” said Sammael. “I had a bit of business to sort out. Your presence wasn’t necessary.”

“What sort of business?”

Sammael didn’t reply. Instead, he rolled up his shirtsleeves and bent over the young girl’s corpse, placing his bony palm against her shoulder. For a moment nothing happened, then the girl began silently to disintegrate. Her skin puckered and shriveled, twisting into knotty lumps. The features on her face crawled toward each other and screwed themselves up into twists. Her eyes shrank into raisins, her lips into a tiny walnut.

After a few seconds, she seemed to be weeping through the pores of her skin, but it wasn’t water that oozed out. Grains of sand were pushing themselves between the stitches of her clothes and forming little mounds, spreading in a mass over the smooth stone floor.

It took less time than usual. She must have been very small.

Sammael picked up the pile of clothes, shook them out carefully so that each clinging grain was returned to the floor, then chucked them into a corner. He surveyed the sand. A pathetic amount. Hardly worth the effort.

“I should have given her more time,” he muttered. “But she didn’t think to ask for any. All this one wanted was to be able to slide down a rainbow. Can you believe it?”

“Only that?” asked Kalia. “She didn’t ask for anything else at all?”

“Only that,” said Sammael. “She could have demanded hundreds of years in exchange for her soul—she’d no idea what it was worth. But she sold it to me in exchange for the power to slide down a rainbow. And then she got to the bottom of the rainbow and fell straight into the middle of the sea. Drowned in minutes.”

He looked at the lurcher. Her tail wagged.

“You didn’t sell yourself so short, did you?” he said. “You’ve gotten all you wanted out of me. You could have all the rainbows you like, without giving up a second of your life for them. Here you go.”

He stooped down, picked up a couple of grains of the sand, and cast them into the air. A rainbow blazed up along their path, filling the room with light of every color. It hung for a few seconds, caressing the faces of dog and master, then swooped into a corner and exploded into a shrieking fire of emerald green. Sammael watched the fire as it gradually died.

The dog pattered forward and pressed herself against his leg. Fingers like icicles brushed her head.

“Old mutt,” he said. “Come on, let’s get this lot stored away with the rest. There’s enough sand there now to put dreams into the heads of a million creatures.”

As Kalia gazed up at his shuttered face she saw a flicker of muscles across his cheeks, pulling his mouth into something that could possibly have passed for a human smile.

“What things they could have done,” he said softly. “What dreams I could have given them.”

Then the smile vanished completely. “But it’s too late now. They should have thanked me while they had the chance. It’s too late for them all now.”

And he turned away to fetch his brush.

* * *

The strange brush was made of some kind of hair, although the strands were so fine that Kalia’s own hairs seemed like fat dreadlocks beside them. It swept up every single grain of sand, so that nothing escaped or was wasted, but she’d never dared ask whose hairs it was made from. Instead she watched as he methodically cleared the floor until the stone slabs were spotless again.

When he’d swept the last of the girl’s sand into a box and balanced the box on top of a neat stack, he put his coat back on. The coat smelled of earth, rain, and age.

“Right,” he said. “Let’s go and see what that storm left behind.”

Kalia trotted after him. She had to press herself to his legs while they stepped through the doorway, so that he remembered to reach down a hand and take hold of her wiry hair. Sometimes he went too fast and she didn’t get to him in time, then she had to travel alone through places that no mortal creature should ever see, between the solid world of the earth and the high, thin air. They did odd things to a dog, those places. The last time she’d been separated from her master, she’d ended up with purple feet and ivy growing out of her toes and curling up around her legs.

Sammael had laughed and cut off the ivy, but he’d left the purple hair growing on her feet.

“Teach you to meddle, mutt,” he’d said. “Teach you to sell yourself into things you’ve no idea about. Although I suppose the purple does add a certain point of interest to your otherwise dull legs.”

She’d tried licking her feet. The purple hadn’t budged. Sometimes she looked down at it and thought it might be spreading up her legs, but it was hard to be sure.

No more mistakes, though. She leaned close up to his legs this time. Stretching tall out of scuffed old boots, they were as hard as lampposts.

* * *

By the time they’d walked the entire path of the storm, all the way from the hills where it had gathered to the island where the last raindrops had been squeezed from its clouds, Kalia’s purple feet were sore and stuck with thorns. She flopped down in the shade of a bush and began gnawing at her pads.

The bright June sunshine shone above them. They had stopped on a shingle beach, which fell flat and gray back toward the sea. A couple of terns sat dozing over their nests, but nothing else stirred along the beach, apart from the dry wind.

Sammael frowned. He fished out a notebook from his trouser pocket and flicked through it. Its pages were thinner than spider’s-web silk.

“The storm should have left another taro behind,” he said.

“A taro?” asked the lurcher. “Haven’t you picked it up yet? There’ve been loads of sticks and acorns and things—I thought it was always one of them.…” Her voice trailed off for a moment, and then, before she could sigh, she said very faintly, “Does that mean we have to go back again and look for it, all that way?”

“Of course not, you fool!” snapped Sammael. “I would have found it if it’d been there!” He ran a finger down the page of writing. “But I suppose one can’t always be sure with storms. What a waste of time. Except I did sort out those idiots.”

“Idiots? Oh … you mean those two humans in the cold-smelling house. What did they do?”

“They were dabbling in storms, trying to find out how to ‘control’ them. Control them! Hah! I thought I’d show them a little bit of what they were up against.”

His mouth twisted into a scornful smile. Kalia was about to ask what he’d done with the humans when an urgent twinge across her well-kicked ribs reminded her that he disliked too many questions.

Then Sammael’s head went up and his jaw clenched. Kalia hadn’t heard anything, although that wasn’t unusual. Sammael’s ears were sharper than those of any earthly creature. He listened for a while, the sunlight prodding at his thick black hair. When finally he relaxed again, Kalia stole another long gaze at him.

“It’s that flying ant,” he said. “I knew something was wrong.”

The flying ant had come a long way from home to deliver its news. Although its tiny wings were exhausted, it shifted anxiously and tried to give over its message as quickly as possible.

“… The boy picked up a stick and spoke, right out loud, spoke so’s I could hear … and the grass went very still and the tree shook, so something must’ve gone on with them, too. Humans talking! How would that happen? It’s never happened before, not that I know of.…”

“A human talking? Indeed. And you heard him?” Sammael watched the ant on the back of his hand, treading at his pale skin.

The ant was too worried about leaving to give more than a glance back at him.

“I did. He said ‘hello.’ Just ‘hello,’ and a couple of other things that didn’t really make sense. But it must be because of something you’ve done, mustn’t it? I thought that when I was halfway here. I thought, I don’t know why I’m going off to tell Sammael—it must be something he’s done, anyway, given this human the power to talk in exchange for his soul. You’re the only creature who could do something like that. You made me able to fly farther than any other ant in the world—no one else could have done that, could they?”

“Hmm,” said Sammael. “A stick, you said. You’re sure he picked up a stick?”

“Just before he spoke, yes. A stick from the tree that had been struck by lightning.”

Sammael thought, for longer than the ant could bear. Visions of being grabbed by sentry ants and dragged before the queen began to screen through its mind—of being accused of that most heinous of ant crimes: Desertion of Duty. Its feet twitched. “But if it’s a problem, you can just take his powers off him again, can’t you?” it twittered. “I mean, like I said, I don’t know why I thought I should come and tell you about it, only I suppose it did seem so strange at the time.… Look, I really have to go.…”

“Scared of your little ant friends, are you?” Sammael raised an eyebrow. “But you can fly forever. Why don’t you just fly away from them?”

“I’m an ant,” said the ant. “I can’t live without other ants. Please … please, I have to…”

“Go.” Sammael waved his hand, and the ant flew through the air. As soon as it landed, it spun on its hind legs and scrabbled at the ground, then hurtled away.

Sammael didn’t bother to watch it go—it was just an ant. Instead he stared at his hands and faced a couple of unpleasant facts. There had been a taro. And somehow, although it was the kind of thing that ought never to have happened, it had been found by a human. Was it as the ant had said? Was the human beginning to uncover the taro’s power?

There was really only one thing for him to do. And it had to be done quickly, before mere uncovering turned into full understanding.

Sammael clicked his fingers to Kalia. “Get up,” he said. “We’ve work to do.”

Kalia wasn’t sure she’d followed all the stuff about the stick and the talking and the lightning, but she’d managed to remove the final thorns from her paws. Her pads still stung. Standing up would be painful, especially on the sharp stones of the beach.

“My feet do hurt an awful lot.…” she whimpered.

“Fine,” snapped Sammael, turning his back on her. “Find your own way home.”

Kalia scrambled up and leapt after him. He’d already taken three giant strides toward the sea’s edge by the time she caught up. “Wait! I can’t go back without you! You know what happened last time!”

“Bah! You can turn into an entire forest full of purple ivy for all the difference it makes to me.”

Sammael’s face was motionless, his eyes tight and hard. As he strode over the shingle toward the sea, Kalia raced to stay with him. Once he started walking, unless he was kind to her, she could never keep up—he could walk faster than the wind if he chose to. Or he could just go back through the strange lands into the room and come out again wherever he pleased. Mostly he avoided doing that when she was with him, but Kalia hadn’t seen him this angry since he’d used the sand to put an idea for making a telephone into the head of a man called Bell. And then Bell had taken all the credit of course, and Sammael had been driven even wilder than usual; the lurcher suspected it might have been an idea he was particularly proud of.

There was nothing proud about him now. He reached a hand out to grab the back of Kalia’s neck so she could stay with him, but he didn’t look at her and he didn’t speak anymore.

* * *

As they swept together into the whispering sea, her bruised pads and bony knuckles scraped over the pebbles and knocked against sharp rocks hidden just under the surface of the water. Sammael didn’t swim. When he crossed the sea, each foot touched the top of a wave and stayed firm against its crest. But Kalia had been born a dog, just like any other, and the waves wanted to swallow her up. Especially now, when Sammael was paying no attention to her.

She gasped for breath as the waves smashed over her nose. Sammael’s hand tightened on the hair at the scruff of her neck.

“How can some numskull blundering human have got his hands on that?” He yanked at Kalia’s neck as a large wave rose up, curling in front of them. She choked but was saved from the stinging spray.

“Does it—urgh!—does it matter?” She struggled for more air as his grip tightened so much that her own neck skin nearly throttled her.

“Of course it does!”

She should have saved her breath. He never got angry without good reason.

“But what could a human do with it?”

With relief she spotted the mainland thickening the horizon ahead. They’d be there in seconds. Kalia didn’t suppose for a moment that Sammael would answer her last question, but talking at least stopped her from thinking about the leagues of sea below.

However, once he’d dragged her up onto the next beach and begun walking over firm ground again, he let his pace slacken a little and, after a long silence, began to speak.

“A human could do all sorts of things with that stick,” he said.

The sand dunes whizzing by beneath them turned into scrubby seaside fields. Sammael vaulted over hedges and gates, as weightless as a paper bag on the wind. But Kalia wasn’t sure about the way his chin had sunk down into the collar of his coat. This was usually a sign of evil rage, the lasting kind.

She glanced nervously up at his face. A dark flame had begun to dance in the pupils of his eyes, and his skin flickered with shadow.

A cloud rolled over the sun. Kalia shivered as the breeze cut through her shaggy coat. She longed to sit on his feet and prevent him from going back to wherever this lightning was supposed to have fallen. Nothing could go well when Sammael gave himself up to white-hot fury.

“I’ll kill him,” said Sammael. “That brat is a walking barbecue already.”

“Couldn’t you just take the taro off him?” Kalia ventured, shuffling a little closer to his boots.

He landed a kick on her ribs, sending her flying sideways. She scrabbled to stand upright, shaking earth out of her ear.

“You forget yourself, Kalia,” said Sammael. “Do you think I need a dog to suggest ideas to me? The taro’s his now. If I yanked it from his dead fingers, it’d still be his. But at least if he were dead, he couldn’t use it.”

“I was only asking,” Kalia whimpered, licking her bedraggled fur where his boot had stuck wet mud to it.

Sammael continued walking toward some distant hills, leaving the lurcher no time to explore her bruises. She raced to keep up with him, ignoring the pain in her ribs. He was muttering to himself; it wasn’t until she’d sprinted right up close again that she heard what he was saying.

“Merry Old England.” The words, full of scorn and venom, barely reached Kalia’s ears before they were swept away on the breeze from the distant sea. “I’ll turn those gray clouds of yours jet black, as soon as I’ve dealt with him. That’s a promise.”

And Kalia the lurcher, who had been born in Shropshire and learned to love the wide-open green of the hills that she’d raced over as a young dog, had to close her eyes for the briefest of seconds against a sharp stab at her heart.

I’m his dog, she told herself. His dog. And I’ll always stand by him, no matter what.

“Good,” said Sammael, looking down at her with a nasty grin on his thin lips. “You know your place, dog. And now I’ll teach this human exactly where he belongs too.”