![]()

The capital of Shang was a city of cosmic order,

The pivot of the four quarters.

Glorious was its fame,

Purifying its divine power,

Manifested in longevity and peace

And the sure protection of descendants.

THIS ANCIENT POEM IN ALL PROBABILITY PRAISES ANYANG, THE LAST capital of the Shang kings who ruled north China from around 1650 to 1027 BC. Prior to the foundation of Anyang, or Great Shang as it was called in oracle inscriptions, the Shang dynasty had moved its capital on several occasions. The first requirement of a Chinese kingdom was a permanent capital, but these frequent moves were a necessity until the perfect location—the location that most pleased the Shang kings’ divine ancestors—was discovered.

Even before the birth of Confucius in 551 BC, the pivotal importance of the ruler as the Son of Heaven formed the basis of Chinese thinking about politics. From Shang times, the earliest period in which written records were kept, we know how all earthly power was believed to emanate from the One Man, the king who was the Son of Heaven: only he possessed the authority to ask for the ancestral blessings, or counter the ancestral curses, which affected society. It was Shang Di, the high god of Heaven and the ultimate Shang ancestor, who conferred benefits upon his descendants in the way of good harvests and victories on the battlefield. Through divination the advice of the Shang king’s immediate ancestors could be sought as to the actions most pleasing to this supreme deity.

Hence King Pan Geng’s anxiety lest his people dally in an unlucky capital. In the Book of History, a collection of documents edited during the fourth century BC, are recorded the difficulties faced by Pan Geng when he wished to move the capital. Speaking firstly to the most senior members of his court, he countered their resistance with these words:

Our king Zu Yi came and fixed on this location for his capital. He did so from a deep concern for our people, because he would not have them all die where they could not help one another to preserve their lives. I consulted the tortoise shell and obtained the reply: “This is no place to live.” When former kings had any important business they paid reverent attention to the commands of Heaven. In a case like this they were not slow to act: they did not linger in the same city. If we do not follow the examples of old, we shall be refusing to acknowledge that Heaven is making an end to our dynasty. How small is our respect for the ways of former kings! As a felled tree puts forth new shoots, so Heaven will decree us renewed strength in a new city. The great inheritance of the past will be continued and peace will fill the four quarters of our realm.

Separately Pan Geng charged his nobles with stirring up trouble amongst “the multitudes through alarming and shallow speeches,” a grievous crime, he pointed, out considering how their own ancestors shared in the sacrifices offered to former kings. Unless they treated the ruler, the One Man, with sufficient honor and loyalty, Heaven would inflict inevitable punishments. In order to ram home his point, Pan Geng then addressed the multitudes, who were “charged to take no liberties in the royal courtyard and obey the royal commands.” He told the people of the reasons for the removal, stressing the calamity the founder ancestor of the dynasty would surely inflict on the existing capital, and let it be understood that nothing would affect his “unchangeable purpose.”

Having won the day by direct speech, Pan Geng transferred everyone across the Yellow River to Anyang, where he instructed his officers to “care for the lives of the people so that the new city would be a lasting settlement.” The episode is interesting for a number of reasons. Implicit are the cosmological threats of the priest-king to invoke the royal ancestors in order to punish dissidents, yet Pan Geng’s conviction of impending disaster if there were no change of site was sincere: he genuinely believed that only his “great concern” stood between the Shang and their ruin.

Again it was Heaven that had given the crucial sign via the cracks on the tortoise shell. Always closely related to ancestor worship in ancient China was divination from the cracks that develop in scorched tortoise shells or animal bones. By 1300 BC divination had become elaborately standardized; Shang kings used only such oracle materials after they were expertly prepared. On them were inscribed the questions to be asked of the ancestral spirits, and sometimes even the answers received.

How then could Pan Geng afford to ignore a warning that his divination had so clearly revealed? “When great disasters come down from Heaven,” he commented, “the former rulers did not fondly remain in one place. What they did was with a view to the people’s welfare, and so each moved their capital to another place.” Only the conspicuous absence of a surrounding wall has caused doubt about Anyang as a capital. Was it rather a Chinese Delphi, whose purpose was principally oracle-taking? We still cannot be sure, as excavation is still patchy outside the royal cemetery and palace. It is possible that the last royal seat of government was so large and its garrison forces so concentrated that a rampart was thought to be unnecessary. On the other hand, the destruction of Great Shang in 1027 BC could have been made easier by Anyang’s apparently sprawling layout. That year the city was razed to the ground.

Notwithstanding its undiscovered defenses, Anyang was the last known residence of the Shang kings and the place where the cosmology of the Chinese capital assumed its distinctive form. Employing the rammed earth method of construction, “the multitudes set their plum-lines, lashed together the boards to hold the earth and raised the Temple of the Ancestors on the cosmic pattern.” In this building, according to the Book of History, “the king used the tortoise shell to consult the ancestral spirits, after which the court and the common people agreed about a course of action. It is called the Great Accord.”

This passage captures the patrimonial nature of Chinese rule, royal or imperial. The authority of the Shang king over his people was simply an extension of his patriarchal control over his own family, an idea later developed by Confucius into a political justification for the state. Since this influential philosopher viewed the state as a large family, or rather a collection of families under the care of a leading family, the virtue of obedience was the key characteristic defining the relationship between a ruler and his subjects. When asked about government, Confucius replied: “Let the prince be a prince, the minister a minister, the father a father, and the son a son.” So China could be described, indeed as it often is today, as “the Hundred Families.” While he regarded correct familial relations as the cornerstone of society, Confucius possessed a profound sense of personal responsibility for the welfare of mankind. After his philosophy became dominant under the Former Han emperors in the first century BC, the Chinese empire’s administrators came to see themselves as protectors of the people, inheritors of Pan Geng’s fatherly concern for their wellbeing.

The special sanctity of the ancestral temple derived from its closeness to Heaven. It was the point at which two worlds met in the sacrifices conducted by the wang, “the king.” This Chinese character is actually written in such a way as to reflect this cosmic relationship. The three horizontal strokes represent heaven, earth, and humanity, with a vertical stroke joining them together. The later character for emperor, di, retained this etymology but added the notion of divinity, or at least divine favor.

The first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang Di, was pleased to adopt the title in 221 BC, the year in which he became sole ruler, because it allowed him to associate his dynasty with the semi-divine rulers of legendary times. In Qin Shi Huang Di’s title, however, there was more than an element of political calculation; his superstitious nature already inclined towards the supernatural elements of Daoism (Daoist thinkers, the perpetual opponents of Confucius and his followers, particularly revered those early divine kings). Qin Shi Huang Di was fully aware of the manner of the Yellow Emperor’s departure: after giving his kingdom an orderliness previously unknown on earth, this legendary ruler was carried heavenwards on the back of a dragon, along with his wives and his ministers. Endeavoring to attain a similar immortality, Qin Shi Huang Di in 219 BC began his attempts to communicate with the Immortals so as to acquire the elixir of life.

Underpinning the layout of the ancient Chinese capital, with its ceremonial center for royal ancestor worship, was a conscious attempt to mirror the cosmic order itself. Like major cities in Indian Asia, it was designed as a parallel, a miniature version, of the patterns observed on earth and in the sky: the succession of the seasons, the annual cycle of plant growth, the movements of the sun, moon, and stars. This acceptance of mankind’s place in the great sweep of the natural world was sustained by a conviction that, although everything which existed was the handiwork of the gods, there were a few places on earth where sanctity was at its greatest. One of these was the ancestral temple of the ruler, the organizing feature of every Chinese capital. Around it the walls and streets were built to maximize the political power and religious authority of the ruler, the One Man who sat upon the dragon throne, facing south.

From the reign of Tang, the first Shang ruler, we can observe how close the relationship was understood to be between the ruler and the natural powers. Having seized power from the semi-legendary Xia kings, whose tyranny and corruption it is said invited their overthrow, Tang informed his subjects about the doubts he had over his worthiness to rule. He said:

“It is given to me, the One Man, to secure harmony and peace. But I know not whether I offend the powers above and below. I am fearful and trembling, as if falling into a deep pit. Throughout my realm I command, therefore, that all abandon lawless ways and fulfil their proper duties so that we receive the favor of Heaven. The good in you I will not ignore and the evil in me I will never excuse. I will examine everything with Heaven in mind. When guilt is found in my subjects, let it fall upon me, the One Man. When guilt is found in me, I will not let it fall upon anyone else. Only through sincerity will we be able to find peace.”

Little did Tang expect these words to come back and haunt him so quickly, but it was not long before north China was struck with a prolonged drought and, believing himself responsible for the calamity, he offered his own life in appeasement. We are told how Tang prepared himself spiritually for the sacrifice. He cut his hair, clipped his nails, and donned a robe of white rushes before riding to a mulberry grove in a simple carriage drawn by a team of white horses. There, as the king was about to die as a sacrificial victim, the drought ended in a heavy downpour.

So impressed was Tang by the rain-making dragons Heaven had sent that he composed a poem of thanksgiving called “The Great Salvation.” Now demonstrably blessed, Tang had no hesitation in demoting the untrustworthy deity he blamed for the drought, an action that shows how in ancient China the spiritual and human worlds always complemented each other. Both were imagined as feudal in structure, with the spirits of mountains and rivers styled “duke” or “count.” That Tang could remove the offending god from his fief seemed perfectly reasonable. As the Son of Heaven, the Shang king was only acting as Heaven’s deputy on earth, where the dire effects of the drought were felt. Just as he delegated a portion of royal authority to own trusted relations, aristocrats, and frontier defenders, so Tang took advantage of the trust Heaven obviously placed in him to make this change in delegated divine duties.

Thus the Chinese conceived the natural features of the world essentially as an extension of themselves. Divine and human were intimately connected through kingship, an institution that elevated the current occupant of the throne into a truly charismatic figure. The king’s subjects were persuaded of an invaluable link between the sacred and the secular by means of rites that dramatized the king’s direct relationship with the heavenly powers. As the Book of Rites puts it, “Rites banish disorder just as dikes prevent floods.” In the ancestral temple and other sites of royal and imperial worship, ritual specialists ensured that ceremonies were conducted appropriately.

The focus of creative energy was, of course, the palace. It was here that communication was effected most readily between cosmic planes, between earth and Heaven on one hand, and between earth and the underworld on the other. This central axis of the Chinese universe was never fixed. As we saw, the Shang king Pan Geng realized his capital was in the wrong place and, on advice from his ancestors, shifted the capital to Anyang. Changes in the sites of royal and imperial capitals were accepted as a necessity, even when a move was due to dynastic weakness.

For example, the Zhou, the dynasty that followed the Shang, was obliged to take refuge at Luoyang in 770 BC. That year King Ping hurried to Luoyang from Hao, just west of the modern city of Xi’an in Shaanxi province. Hao had been destroyed through an alliance of barbarian tribesmen and relations of the queen, who had been set aside because of the preference of Ping’s father for a certain concubine. The ruler was slain, but with the aid of the great vassals, the shaken dynasty survived. A new royal residence had to be built at Luoyang, a safe distance down the Yellow River valley. As a result of the unrest, Zhou prestige declined and real power shifted to the nobles who held the largest fiefs. Despite this fundamental shift in political authority, the removal from Hao to Luoyang came to be regarded as the curtailment of Zhou spiritual power in the face of superior earthly influences, rather than the military catastrophe it actually was. Like previous Chinese capitals, Luoyang acquired a symbolic significance of its own as soon as the Son of Heaven stayed there.

The last Zhou king was dethroned in 256 BC by the forces of Qin, the feudal state from which Qin Shi Huang Di made himself the master of China. This first emperor was much influenced by two ancient schools of thought, the Five Elements and Daoism.

Water was the element Qin Shi Huang Di and his subjects believed to be supportive of his imperial (and even immortal) aspirations because Water had overcome Fire, the element associated with the previous royal dynasty, the Zhou. Prior to the overthrow of the last Zhou king in 256 BC there was already a view that the era of Fire approached its end. The so-called school of the Five Elements maintained that each period of history lay under the domination of one of the five elements—Earth, Wood, Metal, Fire, and Water—and that these elements succeeded each other in an apparently endless cycle. So in turn each element overcame its predecessor, flourished for a fixed period, and then was in its turn overcome by the next element in the series. For the half millennium down to the triumph of Qin, the Zhou king had been reduced to a ceremonial role within a small domain surrounding the royal capital of Luoyang. Supposedly loyal to his commands as the Son of Heaven, the feudal rulers of the rest of China gradually turned their lands into independent states, and then competed for supremacy over their peers. During this intense struggle, the final stage of which was known as the Warring States period, feudal rulers eager to replace the Zhou dynasty sought the protection of Water, the next element in the series. Just as water quenches fire, so Water would extinguish the Fire protecting the Zhou king and hand the heavenly mandate to rule to another.

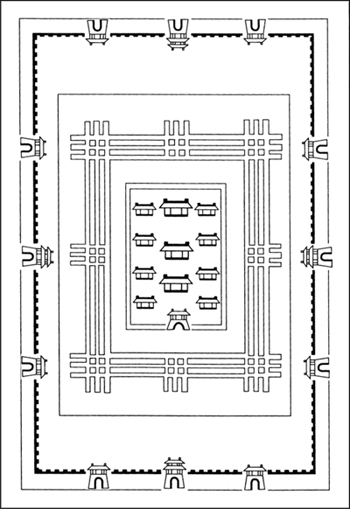

Idealized plan of Luoyang, the Zhou king’s capital

Exponents of the Five Elements school traveled from feudal court to feudal court, receiving the highest honors, as they assured one ruler after another that they were in line for Water’s patronage. Coming from the comparatively unsophisticated state of Qin in the northwest of China, Qin Shi Huang Di found the theory of the Fire Elements utterly irresistible.

Qin Shi Huang Di’s determination to introduce orderliness in his kingdom arose from his belief in the Five Elements. In order to inaugurate the power of Water, the element of the Qin imperial house, Qin Shi Huang Di believed that there must be firm repression with everything determined by law. Only ruthless, implacable severity could make the Five Elements accord. So the law was harsh and there were no amnesties. Black became the chief color for dress, banners, and pennants, and six the chief number. Tallies and official headgear were six measures long, carriages six measures wide, and imperial carriages had six horses.

It was Qin Shi Huang Di who introduced a new dimension into the rituals at Mount Tai, the dominant peak on the northeastern China plain. Possibly his other irresistible obsession—that of the Daoist theory of the elixir of life—led to the association of this peak with the island of Penglai, the dwelling place of the Immortals. The earliest reference to human immortality occurs in The Book of Zhuangzi, a Daoist text dating from the fourth century BC. It provides the standard description of “an immortal hermit with skin like ice, and gentle and shy like a young girl. He does not eat the five grains, but sucks on wind, drinks dew, climbs up on clouds and mist, rides a dragon, and wanders beyond the four seas.” Most important for Qin Shi Huang Di was the ability of an immortal through a concentration of spirit “to protect creatures from sickness and disease as well as ensure a good harvest.” Daoists distinguished three kinds of Immortals. First, there were the celestial immortals, who were able “to raise their bodies and souls high into the sky.” The second kind were the terrestrial immortals, the inhabitants of the mountains and the forests. The last were the corpse-free immortals, who simply sloughed off the body after death. Where this third kind of immortal resided is unclear, although Qin Shi Huang Di may well have been aiming to become one himself at Mount Li, the site of his incredible mausoleum.

When in 110 BC Wu Di became the first Han emperor to sacrifice at Mount Tai, the rituals had to be improvised for the good reason that Qin Shi Huang Di’s sacrificial rituals remained secret, a circumstance which almost certainly related to advice he had received about keeping his own movements and activities out of the public eye. In 212 BC a Daoist adept had warned him

that a sinister influence was working against the search of immortality. It is my sincere opinion that Your Majesty would be well advised to change your quarters secretly from time to time, in order to avoid evil spirits; for in their absence an Immortal will surely come. An Immortal is one who cannot be wet by water or burned by fire, who endures as long as Heaven and Earth.

On hearing of this impediment to his greatest wish, the elixir of life, Qin Shi Huang Di ordered that all his palaces and pavilions were to be connected by causeways and covered walks, so that he could move unobserved between them. Disclosure of his whereabouts was also made punishable by death. How set Qin Shi Huang Di was on achieving his goal became obvious straightaway. From one of his many residences, he noticed the approach of Li Si and commented adversely on the size of that minister’s retinue. A palace eunuch informed Li Si of the emperor’s displeasure, and Li Si prudently reduced the number of his retainers. Qin Shi Huang Di, far from being pleased by this turn of events, was enraged to realize one of his attendants had provided information that revealed his whereabouts, if only by implication. He was so enraged, in fact, that he had all the eunuchs in his company executed, as none would admit to telling tales. “After this,” we learn, “his movements were treated as a state secret, but it was always in the main palace at Xianyang, the imperial capital, that he conducted official business.”

The less private sacrifices that Wu Di made at Mount Tai involved the transmission to Heaven of imperial desires, sealed in a ritual jar, and the worship of the earthly powers. In essence, these rites were the same as any emperor performed in the imperial capital. Like Qin Shi Huang Di, though, Wu Di was involved in other rituals of his own aimed at finding the elixir of life. On his climb to the summit Wu Di was accompanied by a single servant, who died shortly afterwards.

Shrouded as they are in mystery, the visits Qin Shi Huang Di and Wu Di both made to the summit of Mount Tai reflect a real worry about the length of their personal reigns, an uncertainty neither of them felt they could resolve in their own imperial capitals. By then the Shang option of moving capitals to more auspicious sites was really out of the question. Imperial houses now had to propitiate the divine largely by cosmic practices inside their permanent places of residence.

That the Daoist-inclined emperors like Qin Shi Huang Di and Wu Di felt it necessary to travel to a sacred mountain in order to make a personal sacrifice reveals how the ancient Chinese were never really happy with a symbolic replica. This was not the case in Indian-inspired cosmology, the other great Asian tradition. In the kingdoms of Southeast Asia, for instance, the planning of capital cities often depended upon the delimitation of sacred space, the area immediately surrounding a structure designated as Mount Meru, the Indian world mountain. Unlike the Khmer kings of Cambodia, who build temple-mountain tombs deifying themselves in accordance with Indian tradition, China never designed a capital around the sanctity of a king or an emperor, and never gave precedence in its layout to mausoleums for reigning or deceased rulers. Except in the ancestral temple, the realms of the sacred and secular were at all times kept firmly apart. Whereas Khmer temple-mountains faced east, again in accordance with Indian religious ideas, important Chinese buildings, especially the palace, always faced south. “To face south” became synonymous with “to rule.”

The form of a Chinese capital, when terrain permitted, was rectangular, surrounded by wide water-filled moats. Regularly spaced gates were placed in its four walls, with main streets leading to the palace and other prestigious buildings. In the very center there was invariably a drum tower, whose function was the maintenance of civil order and not the worship of a divine ruler like the centrally placed temple-mountains of Cambodian capital cities.

Although some emperors were more drawn than others to the spirit world, the this-worldly tenor of Confucian philosophy set the prevailing tone for dealings with the supernatural. While the Cambodians might incarnate Indian deities in their living kings, the Chinese came to populate the spiritual realm with bureaucrats. This extension of the ways of the imperial civil service into celestial affairs, not unlike the Shang king Tang’s earlier transfer there of feudal obligations, derived from the level-headedness of Confucius’s outlook. Not even divination escaped his censure, since Confucius felt that Heaven was far above human comprehension—something not plumbed by scrutinizing the cracks made by heat on animal bones and tortoise shells. Nor could natural phenomena, like shooting stars, earthquakes and floods, be so readily interpreted as signs of heavenly disapproval.

The reluctance of Confucius to pronounce on religion helped in introducing a sense of balance in the supernatural world as well as the earthly one. “I stand in awe of the spirits,” he said, “but keep them at a distance.” Ethical concepts rather than supernatural concerns lay at the heart of his thinking. What China needed, Confucius believed, were compassionate rulers who would instruct their people by their own example in following traditional usage. He went so far as to warn progressive rulers that the setting down of laws was a dangerous innovation for aristocratic rule. Pointing out that a written law-code represents a break with custom, he astutely predicted that the code of punishments inscribed on a tripod by the ruler of Qin would be learned and honored by people above all else. Never again would those in authority be able to call upon tradition in order to declare their judgments correct. Not for a moment was Confucius suggesting that arbitrary decisions were ever justified. As he said,

If you lead people by regulation and regulate them by punishments, they will seek to evade the law and have no sense of shame. If you lead them by virtue and regulate them through rites, they will correct themselves.

Here the character li, which is usually translated as rites, etiquette, ritual, really means propriety. The way this Chinese word is written tells us what Confucius had in mind, for the strokes represent a vessel containing precious objects as a sacrifice to the ancestral spirits. He saw, therefore, the rite of ancestor worship as the focus of a moral code in which proper social relations were defined: the loyalty of a minister to a prince was the same as that owed to a father by a son.

Under the empire, which lasted from 221 BC till 1912, administrative requirements allowed the service rendered by the scholar-bureaucrat to be a reality as well as an ideal. Confucian scholars connected with the landowning class were one of the twin pillars of imperial society; the other was the great multitude of peasant-farmers, no longer tied to a feudal lord but liable to taxation, labor on public works, and military service. The low social position of merchants—a prevailing feature of Chinese history—was the natural outcome of economic development down to the establishment of the Chinese empire, as feudal princes had assumed most of the responsibility for industry and water-control works. But it was the blocking of all avenues of social advancement to merchants that was the effective curb, because it prevented the sons of successful traders from becoming officials. A poor scholar without an official position would prefer farming to trade as a means of livelihood, lest he spoil any future opportunity of a civil service career. Dedicated civil servants were always expected by Confucius to exhibit good manners, which he believed to be a sign of moral character. For him li encompassed not just the rules of politeness, but rather the correct way of approaching every thought and deed.

Confucianism so deeply instilled an appreciation of the enormous role played by education in civilized society that subsequent Chinese thought can be said to have been an interpretation of this underlying principle. Referring to the Daoists, Confucius said: “They dislike me because I want to reform society, but if we are not to live with our fellow men with whom can we live? We cannot live with animals. If society was as it ought to be, I should not be seeking to change it.” It is a point constantly made down the ages by Confucian scholars whose outlook rested on a sense of personal responsibility for the welfare of mankind. This stress on service, and indeed loyalty to principle, was one of the chief reasons for the adoption of Confucianism as the imperial ideology.

It is somewhat ironic that this began in earnest during the reign of Wu Di, the Han emperor most interested in Daoism. Emphasize though Confucian ethics might the overriding importance of justice, consideration, and good behavior in the administration of the empire, scholar-bureaucrats who adhered to its precepts recognized how they needed to accommodate the spiritual anxieties of the emperors they served. A determined ruler like Wu Di was only willing to worship Heaven on Mount Tai, and hereby acknowledge his moral duties as the Son of Heaven, provided he could conduct on its summit private Daoist sacrifices of his own as well. Even though the imperial pursuit of immortality on Mount Tai ceased with Wu Di, its summit was still held to be one of the routes to longevity and contentment for centuries afterwards. An inscription on the back of a third-century AD bronze mirror tells how on Mount Tai “you will meet the Immortals, feed on the purest jade, drink from sacred springs, and receive a life that lasts ten thousand years, a high official position, and protection for your children and grandchildren.” These remarkable gifts from the Immortals interestingly succeed in combining together the Daoist achievement of the elixir of life with a Confucian respect for public service and family lineage.

The immense cosmic forces believed to be concentrated on sacred peaks such as Mount Tai had to be taken into due account when selecting sites of capital cities and their associated buildings. We know how in 220 BC,

the twenty-seventh year of his reign, Qin Shi Huang Di built a palace on the south bank of the Wei River, which was named the Paramount Temple, representing the Apex of Heaven. From the Paramount Temple a path led to Mount Li where another palace was built. The Paramount Temple was connected with the capital by a walled road.

These buildings, like others he had constructed in and around Qin’s first imperial capital of Xianyang, including his tomb complex at Mount Li, were elements in a grand cosmological arrangement whose focus was actually Qin Shi Huang Di himself, as the Son of Heaven. Just how seriously Qin Shi Huang Di took the spiritual advice that he received is evident in the description of his own burial chamber. In it were placed

models of palaces, towers and official buildings, as well as fine utensils, precious stones and rarities… All the Empire’s waterways, including the Yellow and the Yangzi Rivers, were reproduced and made to flow mechanically. Above, the heavenly constellations were depicted, while below lay a representation of the earth.

Little short of the world itself, this was to be the intended home of an Immortal, once Qin Shi Huang Di’s corpse had been placed inside its copper-clad coffin there.

Qin Shi Huang Di’s architects and planners appreciated how the good fortune of the newly founded imperial dynasty could only be assured if all the sites chosen, and not least that of his tomb, were properly adapted to local cosmic currents, which were calculated by reference to the terrain and the movements of the stars. This ancient geomancy, ancestral to present-day feng shui, always informed the construction of major Chinese cities, and especially royal and imperial capitals. Nothing built for the living or the dead in China was ever planned without the advice of a geomancer. A desirable site was set among land forms generating auspicious, or at least benign, influences, but such locations were sometimes unavailable, so that often geomancers were obliged to concern themselves with defense against evil influences seeping into residences and tombs. The reshaping of hills, the removal of boulders and the excavation of ground considered to be unlucky could help redeem otherwise inauspicious locations, just as the planting of trees and shrubs could assist in restoring a necessary balance of the yin-yang elements. Attuning to the rhythm of nature was a vital consideration for the ancient Chinese, who explained its perfection in the yin-yang theory: it envisaged two interacting forces, not in conflict but existing together in a precarious balance that if disturbed would bring swift disaster. This perception of natural forces could have arisen nowhere else than in the loess country of northern China, where a sudden downpour or a burst embankment might dramatically alter the landscape.

Ever dear to Daoism, this theory also found its way into Confucian ethics. Dong Zhongshu, who persuaded a reluctant Emperor Wu Di to proclaim the state cult of Confucius, argued that the heavenly mandate of an emperor to rule might be upset by an imbalance of the yin and the yang. He said that since human nature possesses little more than the beginnings of goodness, society could only be saved from barbarism through the institutions of kinship and education. He stressed three relationships—ruler and subject, father and son, husband and wife—and insisted that the ruler, the father, and the husband correspond to the yang element and were therefore dominant, whereas the subject, the son, and the wife tended towards the submissive yin element.

Although Dong Zhongshu’s revised form of Confucianism obviously drew on Daoist ideas, we should note how its use of a yin-yang analogy contained no supernatural dimension at all. A ruler’s position of authority was granted and taken away by Heaven, but the agents for affecting change could be humble men like Liu Bang, the first Han emperor, who was welcomed by a people oppressed by the harshness of Qin rule. Liu Bang eventually won, in 202 BC, the complicated struggle between insurgent leaders that followed the overthrow of Qin Shi Huang Di’s dynasty by the first nationwide rebellion in Chinese history.

This dramatic imperial failure was largely blamed by proponents of Daoism and the Five Elements on the shortcomings of geomancy, as the sites of Qin ceremonial buildings were considered to be inadequate for ruling an empire. Had Qin Shi Huang Di still been alive, he would have set about rectifying the deficiency, probably moving around large parts of the first imperial capital in the process. The uncertainties of the feng shui interpretation of landscape were legion: cosmic alignment was a perennial concern, with geomancers endlessly checking that capital cities remained well adapted to the local cosmic currents. These influences, which could suddenly manifest themselves in benign or unsatisfactory ways, needed to be kept under control. Divination might help in the selection of the general location of a capital, but the actual layout of the urban area, the positioning of the palace and administrative center, was something that could not be decided until the geomancers had completed all their calculations. Then the city was laid out as a square, or a rectangle, the surrounding walls usually having three gateways on each of the four sides.

Within these rammed-earth defenses there were nine streets running east-west and nine streets running north-south. The former had to be “nine chariot-tracks wide.” Of Luoyang, the seat of the later Zhou kings, an ideal plan survives: it is not very instructive in showing where the chief buildings were situated as the royal palace is simply placed at the city’s center. If there was one capital that came closest to the sought-after cosmic alignment, it was Sui and Tang Chang’an. This imperial capital was inaugurated by the first Sui emperor, Wen Di, a hard-bitten soldier of Turkish ancestry who was noted for his sternness. In AD 589 he was appalled at the human cost of building his palace there, until his wife expressed her unqualified admiration for their new home. The most henpecked of all rulers in the history of the Chinese empire, Wen Di had no choice in the face of his wife’s approval but accept the danger to his dynasty of placing such a heavy burden of labor on the Chinese people.

Emperor Wen Di was right in being concerned, notwithstanding the perfectly symmetrical plan of his new capital, which stood not far from Former Han Chang’an. He called it Greatly Exulted Walled City. Unequivocal though this statement of imperial will was, the first Sui emperor was not without compassion for the sufferings of common folk, in contrast to his successor, the emperor Yang Di. This younger son assassinated him in 604 and, brushing aside the financial restraint of his father, he commissioned a second imperial capital at Luoyang, which was built by hundreds of thousands of conscripted laborers in the following year. His next project was the digging of the Grand Canal in order to link the northern and the southern provinces permanently together. Added to this were the repairs Yang Di ordered to the Great Wall, as the northern defenses were later called, and the war he started with Koguryo, a Korean kingdom which stretched across southern Manchuria and the northern part of the Korean peninsula. Defeat abroad and insurrection at home ended Sui rule in 618, when Chang’an was captured by Li Shimin, the second son of the first Tang emperor Gao Zu.

Considered as one of the greatest in Chinese imperial history, the Tang dynasty retained Wen Di’s Chang’an as their capital and used Yang Di’s Luoyang as a secondary capital. During the reign of the sixth Tang emperor Xuanzong, who came to the dragon throne in 712, Chang’an was at its greatest with a population of nearly two millions. It was by far the largest city in China, and for that matter in the world. There, good government combined with a surge of creativity to produce what is now termed the Tang renaissance, its most obvious achievement appearing in the Complete Tang Poems, a collection of 48,000 poems by no fewer than 2200 authors.

Although the Tang emperors continued to occupy the halls and gardens built by their Sui predecessors at Chang’an, they made many innovations, the most significant of which, the construction of the Great Luminous Palace to the northeast of the walled city, destroyed the perfect symmetry of the Sui foundation. The Sui palace, stood next to the north wall of the capital, while to its immediate south were situated the headquarters of the imperial bureaucracy. These distinct quarters, the palace and administrative cities with their own walls and gateways, still remained the place where most official business was conducted after the construction of the Great Luminous Palace. Here the Son of Heaven continued to sit upon the dragon throne, facing south and radiating his heaven-granted authority down the great avenue in the very center of Chang’an, and out into the Chinese empire at large. The dragon throne had to be placed close to this avenue’s north-south axis, since it corresponded to the Pole Star, “the very spot where earth and sky met, where the four seasons merged, where wind and rain were gathered in, and where the yin and the yang were in harmony.”

This cosmic consideration was still apparent during the twelfth century at Hangzhou, the southernmost imperial capital. The loss of the northern provinces for a second time then had compelled the Song dynasty to move south, and with reluctance agree that Hangzhou’s irregular and unplanned features could serve as an imperial residence. Marco Polo knew the city by the name of Kinsai, a corruption of “temporary residence,” the only title the Southern Song emperors could bring themselves to confer upon Hangzhou. The basic problem facing geomancers here was the restricted city site, squeezed onto a narrow neck of land, approximately a kilometer in width, between a lake and a river. Yet they did their best to maintain a cosmic layout, despite the placement of the imperial palace towards the south of Hangzhou, and to the west of the central street marking the north-south axis.

The name Kinsai was prophetic. Hard pressed though the Song emperors were by the Jin, the ancestors of the Manchus, there was behind these invaders from the steppes an even more terrifying enemy, the Mongol horde under Genghis Khan. In 1126 the Jin had captured Kaifeng, the first Song capital, and driven the dynasty to Hangzhou, where it became known as the Southern Song. The emperors who had ruled from the northern city of Kaifeng were then styled the Northern Song in order to distinguish them from this southern survival of a shaken imperial house. Only forays against other enemy peoples gave a respite to what was left of the Chinese empire—once the Mongols conquered the Jin in 1234, the full force of their strength was directed southwards. The last member of the Southern Song dynasty perished in a sea battle off modern Hong Kong in 1279; that the Song held out those forty-five years is testimony of the stubborn resistance put up by Chinese armies, exploiting terrain unfavorable to Mongol cavalry tactics.

Another factor in lengthening the struggle was military technology. Explosive grenades and bombs were launched from catapults; rocket-aided arrows with poisonous smoke, shrapnel, and flamethrowers were deployed alongside a primitive armored car as well as armored gunboats; and in close combat a prototype gun, named the “flying-fire spear,” discharged both flame and projectiles. The Mongols, like invaders before them, became irresistible only when they adopted Chinese equipment. Yet they outdid all previous invaders in becoming the first nomadic people to conquer the whole of China. In 1263 the grandson of Genghis Khan and the first Yuan emperor, Kublai Khan, founded Beijing as his capital.

Dadu, as Mongol Beijing was called, seems to have been constructed on the site of a Jin country palace. That it conformed in its plan to a traditional Chinese capital, with a rectangular defensive wall and an inner palace city, tells us much about the motives for the transfer of the Mongol capital from Karakorum to Beijing. Close though Beijing was to the Mongol homeland, it is transparent how Kublai Khan intended to rule as a Chinese emperor as well as a great khan. Yet the Mongol approach to China was quite different from that of the earlier Turks and the later Manchus. Whereas these two invaders became patrons of Chinese culture and in so doing forfeited their own languages and traditions, Mongol emperors preferred to exclude Chinese scholars from office and rely on an administration chiefly staffed with officials of non-Chinese origin.

As a Mongol civil servant, Marco Polo could express admiration of Kublai Khan’s great empire, its cities, commerce and canals, for the good reason that he was unaware of the high level to which Chinese civilization had attained prior to the fall of the Southern Song dynasty. Although the narrative of The Travels opened the eyes of medieval Europe to the magnificence of East Asia, Marco Polo never penetrated deeply into conditions in China, which, during his stay from 1260 to 1269, had scarcely begun to recover from the destructiveness and disruption of the Mongol conquest. The full recovery of China had to await the establishment of the Ming dynasty by the patriot Zhu Yuanzhang, a former monk, beggar, and bandit.

The last Yuan emperor abandoned Beijing in 1368 and fled to Mongolia. Hong Wu, the title Zhu Yuanzhang chose as the first Ming emperor, built his capital at the southern city of Nanjing. It was the third Ming emperor, the usurper Yongle, who moved the seat of restored Chinese imperial power northwards to Beijing. Overruling opposition to the move in a more imperious manner than the Shang king Pan Geng would have ever thought feasible, Yongle ordered his new capital to be laid out within a wall measuring some 23 kilometers in length. This wall followed the outline of the former Mongol city, except that it was about two kilometers shorter at the northern end and about a kilometer farther extended to the south. What Yongle accomplished in moving the capital northwards was a return to the rectangular grid plan of the classical Chinese city, which had reached its perfection in Sui and Tang Chang’an. It was a definite reaction from the irregular cities of south China, and notably Hangzhou.

Despite considerable rebuilding during the late twentieth century, the chessboard pattern of Beijing is still apparent, with the division of the city into distinct quarters. At the center is the Purple Forbidden City, a literary allusion to the Pole Star. Arranged in accordance with this star and adjoining constellations, the Purple Forbidden City has a north-south orientation, all its principal terraces and entrances facing south. Two sacrificial altars attended by the Son of Heaven are still situated to its south on either side of the central avenue describing the capital’s north-south axis, and next to what was once the southern gateway of the outer Ming city. Emperor Yongle performed the sacred rites as the One Man on a single site in the vicinity, but about 1530 it was determined, after a thorough historical investigation by a commission of scholars, that separate altars should be built not only for Heaven and the earthly powers but also the sun and moon as well as other spiritual forces. Within one spacious enclosure today stands the Altar of Heaven, a circular three-tier terrace nearly five meters in height, and the well-known Temple of Heaven, a circular building with a triple roof of blue tiles. In this majestic building the emperor offered prayers during major festivals each year. Nearby is the Altar of Agriculture, whose sacrifices were connected with spring plowing and directed at securing good harvests. It is a direct descendant of the terrace-altars of ancient Shang times.

The last imperial dynasty, the Qing, was initially restricted to north China, since the rest of the empire was embroiled in civil war. Had the Chinese united behind one pretender for the dragon throne, the invading Manchus might have been driven out altogether. As it was, they occupied Beijing and awaited developments. By the time the people of the southern provinces were disposed to unite, there was an energetic Manchu ruler to face, the second Qing emperor, Kangxi. With the assistance of Chinese commanders who accepted that the heavenly mandate to rule had passed already to the Qing dynasty, Kangxi asserted his authority over south China, the last Ming center of resistance on the island of Taiwan falling in 1683.

It was the northern location of Beijing, an imperial capital far removed from where the majority of the Chinese population lived in the southern provinces, that really gave the Manchus their chance to seize power. By quietly occupying the city, and embracing the cosmic implications of ascending the dragon throne, Manchu rulers were able to appear as the legitimate successors of the last Ming emperor, whom they criticized as unfit to rule. One of the important planks of Qing dynastic ideology was the argument that not only had their incompetent predecessors lost heavenly approval, but more the factionalism and strife so evident amongst the imperial civil service was a clear indication that China urgently required a new and energetic dynasty. And the Manchus and the Chinese were both surprised to discover in Kangxi a model ruler. In 1684 we learn that

the emperor visited Mount Tai. He rode on a horse through the Red Gate for a kilometer or so. Then he dismounted and walked up stone stairways for nearly twenty kilometers. After he reached the top of the mountain, he performed the prescribed rituals.

In these imperial duties Kangxi “led the accompanying officials” and “personally prayed” for the well-being of the empire, demonstrating his willingness to be everything expected of the One Man. Afterwards, the Manchu emperor succeeded in putting a distance between himself and any Daoist associations that may have lingered in the Mount Tai rituals by visiting the shrine of Confucius at Qufu, also in Shandong province. There he offered sacrifices to the philosopher as the one “who had given good laws to the people.” He heard the ritual music and listened to lectures; he was shown the famous collection of precious objects and had pointed out to him was the place where a descendent of the philosopher had hidden Confucius’s writings when Qin Shi Huang Di ordered the burning of the books.

Chinese scholars now knew that they need have no fear of Kangxi’s intentions, because his admiration of Chinese culture was genuine and deep. Lacking an advanced tradition of their own, the Manchus were obliged to identify with the Confucian orthodoxy which underpinned the authority of the Son of Heaven. This antiquarian impulse soon generated an encyclopedic movement second to none, and in the fourth Qing emperor Qianlong created a collector without parallel anywhere in the world. It was near the close of his long reign, in 1793, that a British trade mission led by Lord Macartney was politely rebuffed. As Qianlong intimated, China was an empire so vast that it had no reason to engage in international trade.

The nineteenth century was to prove him wrong, as European powers and a modernized Japan lay siege to China: Beijing fell to an Anglo-French force in 1860, when on Lord Elgin’s orders the Summer Palace was fired, and again in 1900 to an international expedition sent to relieve the Legation Quarter, then under attack from the Boxers. Yet Qianlong’s cool response to Lord Macartney does explain why Qing Beijing remained essentially Ming Beijing. Such was the esteem in which the Manchus held Chinese ways, and such was their fear of changing age-old customs, that they were quite incapable of redesigning China’s last imperial capital, lest the whole edifice of the emperor’s authority came tumbling down. They understood how unwise it would be to alter the cosmic arrangements first established by the Shang kings. Nothing was to be gained in disturbing the cosmic layout of an imperial capital which, like all those founded before Beijing, had been “built in the center of the earth in order to govern the whole world.”