AARDVARK

“Earth Pig”

One of a kind.

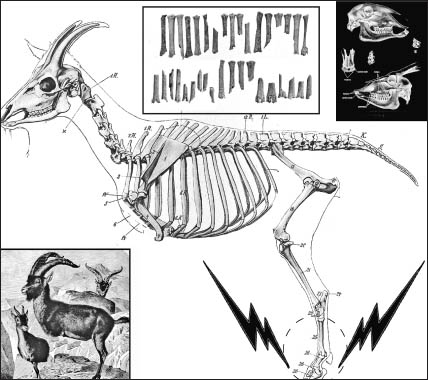

With rabbit ears, a pig snout, a kangaroo tail, and mini-elephant legs, an aardvark seems put together from nature’s spare parts department. The aardvark is actually completely unique—the only surviving member of its own distinct order, Tubulidentata, which means “tube-teethed mammal.” It is also classified as an afrotherian animal, which is a small group of beasts with ancient African origins, including shrews, elephants, and sea cows. Today, aardvarks live only in Africa, in a range below the Sahara Desert to Cape Town. Most people believe an aardvark is the size of beaver, but it weighs more than 150 pounds, growing to over 4 feet in length, not including a 2-foot-thick tail. Its hind limbs have hooves, while its front feet are padded paws with sharp claws. Within minutes, it can dig a tunnel to fit the size of its body, making it faster than five men with shovels and picks.

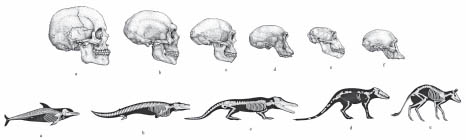

Animated Fossil

Aardvarks existed for more than ninety million years and lived when dinosaurs roamed. The aardvark was there when all sorts of strange creatures appeared in the wake of the dinosaurs’ extinction and probably heard the first songbirds sing. In fact, it certainly witnessed the rise of primates and saw the first upright walking hominid emerging from the forests. Yet, today the aardvark is exactly as it was then. With its unique chromosomes and distinctive physical characteristics, the aardvark is a living animal relic.

Hire an Aardvark

If animals were listed under categories of employment, aardvarks would without doubt work in pest control, specializing in termites. Their appetite for this insect is insatiable, and they never seem content until stuffed with them. Aardvarks are omnivores like us, eating insects, fruits, and roots found along their paths.

Every night of the year, an aardvark shows up for work, making a zigzag line from one mound to another, able to identify the faintest termite pheromone, or scent; it often travels more than 15 miles from its burrow searching for its preferred delicacy. An aardvark punches a hole through a termite mound’s hard, mud-caked exterior. It then inserts its sticky 12-inch tongue deep within the termite nest, trapping hundreds of insects at a time. The aardvark is anatomically qualified for the job.

How It Works

When an aardvark smells termites, its saliva glands produce a sticky resin that is stronger than the adhesive side of duct tape. It rolls and coats its tongue in this thick pool of specialized spit before probing it into the nest. The aardvark also has a distinctive flaplike design that can seal its snout as it munches face-first into termite mounds. This prevents swarms of frantic termites from entering the aardvark’s nostrils, filling up its lungs, and suffocating it.

To solve the problem of all the dirt that inevitably gets caught on its tongue, an aardvark has rows of perpetually growing teeth located on the roof of its mouth and protruding from its cheeks. It has a gizzard stomach, the same as birds and earthworms, made of contracting and crunching muscles that work better when pebbles or stones are also swallowed to aid the digestive process. An aardvark’s stomach is half filled with sand and soil much of the time, though this causes no undue grief, heartburn, or upset stomach.

Does It Play Well with Others?

Aardvarks are loners by temperament, though they join briefly once a year for mating. They usually give birth to only one naked and blind offspring each season, which the mother cares for diligently. Female cubs, or slow-learning males, are sometimes allowed to stay with the mother until the following mating season. After spending six months to a year with her, though, and while still nearly hairless, the young aardvark must leave to dig its own burrow. Afterward, the aardvark begins its existence of solitude, often never socializing with its parents again. From fourteen weeks old, an aardvark begins to eat termites, and like its parents, it will not stop searching for this particular food source for the rest of its life. An aardvark tolerates and avoids other animals that cross its path and rarely picks a fight. However, if provoked or eyed as a meal, it will defend fiercely by planting its backside to the ground, and then start swiping and swiveling at its attacker with lightning-quick claws. As awkwardly shaped as it seems, the aardvark can make a ninja-style somersault to change positions during a fight. Aardvarks usually try to avoid water, as lions do, but can swim skillfully if needed. The Tswana tribe of Africa has said that in the wild an aardvark rarely looks a human in the eye, but if it does, this is extremely bad luck.

An aardvark does not make a suitable pet, since if kept in a backyard pen, for example, it could quickly dig a hole to escape. Feeding an aardvark a sufficient supply of termites would be a greater challenge, though zoos feed captive aardvarks a mushlike substitute consisting of hash, eggs, oatmeal, and milk. The claws of an adult aardvark can slice off a leopard’s nose; aardvarks must be handled with caution, if at all.

Life Cycle

On average, an aardvark that learns to fend off pythons, hyenas, and leopards can live in the wild for twenty years. Pythons are the biggest threat to young aardvarks, but all the large cats and hyenas frequently attempt to eat them, too. Aardvarks also die from snakebites. Where roads intersect terrains, they are regularly found as roadkill, as is the case with many nocturnal animals. Aardvarks are not prone to acquiring any specific diseases, though they tend to become slower, arthritic in old age, and more vulnerable to predators. Most expire in their burrows during the noontime heat due to hunger, too feeble to move. Having a solitary life—unlike wild dogs that feed their elderly—aardvarks usually die alone.

The aardvark somersaults, has a tongue of glue, and an extraordinary sense of smell, though it is nearly blind during daylight. It is a quiet, nonaggressive, and typically unpretentious nocturnal beast.

—

Aardvark was the name given to it by South African Dutch settlers, meaning “earth pig.” In the mid-1800s, Dutch explorer and naturalist Robert Gordon introduced the aardvark to Europe and convinced biologists the animal was not related to an anteater or a warthog. In 1869, the London Zoo was the first to show an aardvark—before that, most thought rumors of such a creature were imaginary. It was not even listed in English language dictionaries until the 1920s, but after that it always made the first page, due to its double A—an alphabetical plus the aardvark taught small businesses trying to get top billing in the phone book.

—

In one year, a single aardvark eats more than eighteen million termites. That amount of wiggling bugs would fill four large bathtubs to the brim.

Magic Animal

The Hausa people of West Africa consider the aardvark an admirable beast, respected for its unstoppable quest for food and its apparent fearlessness: aardvarks seem unafraid when challenged by deadly swarms of soldier ants, which often nestle near, and supposedly guard, termite mounds. Hausa shamans and medicine doctors use the aardvark’s heart, along with powder made from a dead aardvark’s strong claws, for magical concoctions. Aardvark amulets make a person invisible, capable of flying, and able to walk through walls.

“Hey, Aardvark, Where Are You?”

Though no one knows exactly how many aardvarks remain in the wild—they are hard to count due to the animal’s extremely shy personality, underground homes, and nocturnal foraging—the aardvark population is estimated to be 50,000.

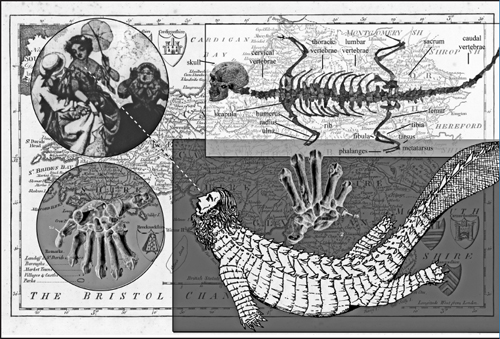

AFANC

Legendary Lake Monster

According to Welsh mythology, this creature lived in the dark, cold lakes of the British Isles. It was crocodilelike, over 10 feet long, and had a large beaver tail. However, centuries-old legends describing this beast differ, with some accounts claiming it had a humanoid face. Others portray the afanc as a dwarf-man-beast with a strange tail. Nevertheless, it stalked with an intelligent craftiness and watched people sitting near the banks, lurking close by undetected for days at a time to observe their every detail. When it finally showed itself, it spoke in humanlike noises and mimicked speech, sometimes even calling out to its intended target by name. Afterward, it usually devoured the stunned onlookers with one bite.

How It Works

The afanc’s tail was multidirectional and had the ability to slap the water flat or swish it back and forth like a canoe paddle. When populations grew too crowded around its secluded lake regions, numerous afanc grouped together and agitated the surface so furiously that flash flooding occurred, destroying villages. According to Welsh myths, the afanc’s powers were useless on land. However, in water, the creature was at its stealthiest best, rarely fooled by conventional fishing methods and impossible to coax from its hiding place.

How to Survive It

Welsh folktales describe how the afanc was finally subdued, after its vulnerability was discovered; the beast seemed mesmerized by the sight of beautiful women, and at first it approached meekly and tried to talk to them softly. The afanc had a quick temper, however, and became frustrated when damsels were horrified by its presence. Records show how towns plagued by this creature actually coerced charming village girls to bait the afanc from its hiding place by having them pretend to picnic near the shore. The girls had to remain calm and look unafraid, encouraging the brute to come closer. Once the beast fell asleep on the maiden’s lap, the afanc was then roped and dragged away. The last one, which legends say was captured by King Arthur, lived in a whirlpool of the river Conway located in North Wales.

Was It Real?

Accounts of dangerous creatures living near remote lakes in Britain were so ingrained in oral history that it was presumed that something weird, in fact, once lived there. Stories of such beasts appeared in numerous written accounts during the early 1500s. The mountains of northern Wales were shaped during the last Ice Age, ending about ten thousand years ago. Humanoid species lived in this area for hundreds of thousands of years. The seas were lower then, and land bridges connected Britain and Ireland to Europe. In 2004, archaeologists discovered twelve-thousand-year-old remains of a hobbit-sized people that once thrived on the island of Flores, Indonesia, and confirmed that bands of hominids no taller than 3 feet, once considered fable, did in fact exist. It is unclear whether the afanc was purely imaginary or an extinct humanlike genus. Other more far-fetched theories suggest it was an anomaly birthed from Jurassic-period eggs of an extinct dinosaur and hatched during the 1500s, when Britain experienced a period of global warming.

Fifty million years ago, there was a real animal, a hairy 2-pound creature called a Castorocauda that had an oversized beaverlike tail and, with its large teeth, feasted ravenously on fish. The afanc might have been such a creature thought extinct, though whatever this beast was, none have been seen in more than four hundred years.

AHUIZOTI

Five-Armed Dog

Christopher Columbus attempted to take inventory of all things found in the New World, including native animals. As indicated by drawings of fantastical creatures adorning antique maps, even the most rationally minded members of the time believed in sea monsters. There was a widely accepted theory that a parallel universe existed, where every animal on land had its counterpart in the sea, though oftentimes with physical characteristics exaggerated or mutated by the unfathomable laws of the ocean. During Columbus’s fourth voyage in 1503, he happened to be stranded in Jamaica for more than a year. In correspondence, he described a strange beast known as King of the Lakes, or “Sun Dog.” Some called it an “ahuizoti,” apparently named after the Aztec emperor Ahuizotl. The creature was the size of a dog with a humanlike or monkey face. It had five hands, with one growing from the end of its tail. It was incredibly strong and according to writings attributed to Columbus, it attacked a Jamaican wild boar with a berserk fury, using its tail-hand to grab the pig by the throat and strangle it.

The beast was also cataloged in a book called the Florentine Codex, written by a Franciscan monk between 1540 and 1585, which described various aspects of Aztec life. This dog-size animal lived either in the water or in damp caves or alcoves and was notorious for being savagely territorial. If people came to fish in the area it claimed, it tangled nets and capsized vessels. The victims of the Sun Dog were dragged below the surface and overpowered by the grasp of the superstrong hand on its tail.

The creature lived in Mexico, in and around Lake Texcoco, but was also observed in Nicaragua. It has not been seen in recent times, though reports of drowning victims in the area found with fingernails missing persist.

Was It Real?

It’s hard to imagine what this creature was, or the actual animal it was mistaken for, yet it is described in numerous verifiable historical records. It is speculated that the ahuizoti was perhaps a type of extinct, fiendish monkey or even a hermitic hominid, though most probably it was a type of prehistoric otter since vanished. Nevertheless, a creature with an extra hand on its tail certainly would have its advantages.

Geographically, Lake Texcoco, before it was drained and modified to conform to the urban sprawl of nearby Mexico City, was once a large natural lake connected to five other lakes that were all more than 7,000 feet above sea level. During the period when different mammals developed, the region and these waters were isolated, not connected to the sea or any rivers, which theoretically could help to give rise to unusual creatures; consider the unique animals that evolved on Madagascar or the Galápagos Islands.

The one it has drowned no longer has his eyes, his teeth, and his nails; it has taken them all from him. But his body is completely unblemished, his skin uninjured.

—FLORENTINE CODEX

Nail Biter

Unbelievably so, the Sun Dog’s desire for fingernails was attributed to a keratin deficiency. Keratin is the protein that makes fingernails grow hard, and with the creature having so many hands, it apparently needed more. Some creatures actually do eat fingernails. In a 1798 maritime manual, sailors were warned of the dangers of working on ships infested with cockroaches. It was recommended to wear gloves while sleeping “to prevent hordes of the insects from gnawing off their fingernails.”

AJA-EKAPAD

Lightning Goat

This mythical one-footed goat lived in India. It had spiraling horns and long, matted fur, with a beard under its chin that extended the full length of its body. It favored mountainous regions and was rarely seen, though, in early Vedic texts (Hindu sacred books, written around 500 B.C.), the beast was represented as a god of floods and a deity that lived somewhere in the sky. The beast was often seen during thunderous lightning storms, perched on cliffs, its silhouette remaining motionless against the storm’s flash of light. Legend believed the one-footed animal caused lightning every time it stomped its foot or when its hoof struck a rock. Vedic writings that mentioned this beast used a combination of words to form the creature’s name, including goat, serpent, and unborn, such that no clear notion of the actual animal meant to be described remains. Aja-ekapad came to symbolize the fundamental energy required to bring inanimate objects to life—or the spark behind creation.

ALBATROSS

Perpetual Flying Machine

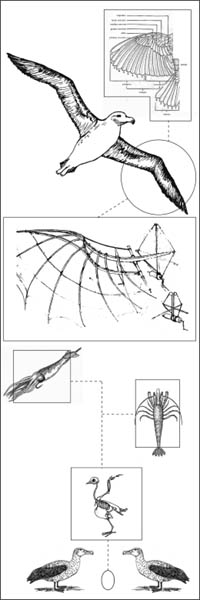

An albatross has the largest wings of all living birds, with an average wingspan of over 11 feet. The albatross prefers the wide-open ocean, only touching land and gathering in prodigious numbers on the remotest outcroppings during mating season. The albatross lays a single egg, which both parents take turns incubating. The parents remain married, so to speak, for a few years and acknowledge the commitment by a ritualized head-bobbing dance, first doing a comic mock sword fight with their beaks. They guide their single offspring until it can take to the wind on its own. The fledgling year-old albatross typically will not touch the ground again, remaining in constant flight for ten years, until it finally touches down on land only after becoming mature enough to breed. There are more than twenty known species of albatross, with the majority found in the southern oceans or near the North Pacific, favoring remote areas void of civilization.

It eats squid, small fish, and shrimp and does not need to drink freshwater to survive. Unlike people, whose salt levels become unbalanced after drinking seawater, an albatross has a built-in desalinizing system and specialized salt-removing glands at the back of its beak. To make freshwater from seawater, the excess salt is extracted and expelled from its nostrils.

Life Cycle

Since they prefer colder air, albatross are less susceptible to diseases than tropical birds, though many do get cholera and various pathogenic bacteria, which usually affect newborn chicks. The new hatchling, after being so carefully tended, frequently dies from these diseases only after a few minutes outside its egg. While airborne, albatross have few natural enemies, but if albatross rest on the ocean, which they regularly avoid, some whales or sharks will snatch or attack the birds when these ocean predators come to the water surface to feed.

True to its majestic spirit, and as a symbol of boundless freedom, an old albatross will take a final flight, if it can, and die while riding the trade winds before tumbling into the sea. An albatross has a long life of more than sixty years. There are about 500,000 pairs of albatross still flying.

The albatross is an expert at surfing the lower air currents, able to glide vast distances without a single flap of the wings. It can circumnavigate the globe in less than two months.

Lucky Charm

In the early seafaring days, spotting an albatross was a blessing and brought good luck, since the birds were considered harbingers of fair winds and smooth sailing ahead. However, this popular perception changed over time. During the 1960s, after a resurgence of interest in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the albatross came to signify an unshakable curse. In that poem, a sailor kills the bird with a crossbow and is then made to wear the carcass of the heavy bird around his neck as a penance. The ship and all the sailors meet a tragic fate, and the Old Mariner remains destined to live forever, telling his tale of woe to whoever would hear it.

An albatross has no need for a nest, except when breeding, since, for most of its life, the sky is its bed. It sleeps in the air while in flight and has the ability to turn off one-half of its brain at a time.

How to Fly Like a Bird

In the 1400s, inventor Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed with flying. Da Vinci purchased pigeons and doves in the marketplace and let them fly off into the air. He made more than four hundred drawings of birds’ anatomy and of flying contraptions, trying to understand the principles of flight. In 1904, another inventor, Victor Dibovsky, believed the solution lay with the albatross. He captured a large one that had a 12-foot wingspan and after studying it, he concluded an albatross glides for such lengths, and for so long, due to the curvature and shape of its back. He built a flying machine with 28-foot-long flapping wings, powered by foot pedals and pulleys. Like da Vinci with his birds, Dibovsky could not duplicate the albatross’s ability. Incidentally, Dibovsky did devise a way for a machine gun, mounted on an airplane fuselage, to fire and shoot without hitting the propellers.

AMMONITES

“Snake Stones”

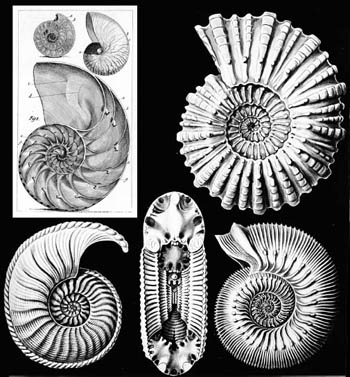

When the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder examined fossils of ram-horn-shaped shells, he assumed they were once pieces of jewelry belonging to the ancient Egyptian god Amun, a deity that was a primeval creator who made the sky and earth, and fashioned creatures from his thoughts. Ram horns were often associated with this deity, and thus the creatures were called “ammonites.” These fossil shells actually belonged to nautilus-like invertebrates, which had been long gone by Pliny’s times, though they had lived in the world’s oceans for over two hundred million years. They disappeared along with dinosaurs about sixty-five million years ago.

These ancient marine animals were so numerous they literally clogged the oceans during their long reign. Many of the fossilized shells remain abundant and intact even to this day.

How It Lived

Life as a prehistoric ammonite was relatively worry-free, despite finding itself in an ocean rife with dangerous beasts, since few thought of it as a nutritious food source, especially since it was encased in a hard shell. In addition, it had another secret weapon and could ward off persistent predators by shooting ink at its enemy, sort of like an underwater smoke bomb, clouding the water, which gave it time to escape. It propelled by tentacles that protruded from its disk-shaped shell, which moved in pulsating unison to gain momentum and allowed it to move to where it wished.

Where Did They Go?

Ammonites had numerous shell designs that grew from less than 1 inch to more than 7 feet in diameter. Most ate plankton, but the largest species likely consumed smaller fish as well. They possibly became extinct because of unusual reproductive habits, since many types of ammonites only gave birth to a giant cluster of eggs once in their lifetime, just before they died. One theory proposes that if an environmentally abrupt change occurred, the total global specimens of egg clusters could have perished during a particularly devastating climatic event. In addition, plankton populations were thought to have diminished drastically due to a blanket of atmospheric volcanic ash that had darkened the skies during the period immediately preceding the ammonites’ elimination. When this primary food source for ammonites dwindled, it likely abetted this creature’s disappearance forever from the oceans.

In medieval times, scientists disagreed with ancient historians and said the ammonite fossils were once coiled snakes that had been transformed into stone for their evil deeds and relationship with the devil, and they called them “snake stones.”

From Many to No More

Extinction is a substantial, fatalistic word. The exact reasons why some species survive and others perish are matters of speculation. Ancients explained the loss of individual animals, such as ammonites, with the principle of “miraculous interposition,” suggesting that God (or one of many gods, as Egyptians believed) simply no longer had a plan for the creature. Scientist Jean Baptiste Lamarck was one of the first to ponder why organisms seemed to disappear. Lamarck was an eighteenth-century naturalist and a curator of a museum in Paris that held many specimens of invertebrates. Lamarck believed that nothing actually became extinct but that the less than “perfect’” moved to a more complex and better organism suited to its environment. There are fossil records, considered the most tangible evidence, of more than 250,000 species that no longer exist. More than 90 percent of all the species that once lived on earth are gone; viewed long term, extinction rather than survival appears to be the rule of the natural world.

AMOEBA

Microscopic Immortal Being

Amoebas live all around us, but they are usually too small to see without a microscope. The largest grows to 700 micrometers, which is smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. However, at any given moment, hundreds are hitching rides on dust particles floating in the air. In a single drop of pond water, there are typically more than one thousand, which, if coerced to stand in a straight line, would measure less than 1 inch. Amoebas have jellylike bodies or cytoplasm held in loose form by a membrane. An amoeba can change shape and look like an ink splat; it can be oval or form into a shape with a number of peninsula-like extensions. Inside it has a nucleus, its brain, of sorts, but it has no eyes, ears, arms, legs, or mouth. Although it does not hear or see—or so we think—it is fully equipped to survive and even flourish to the point of being almost immortal. An amoeba strives to find a moist environment—a stagnant puddle of water would do—where its whole being entwines with its fluid mini-universe and nearly becomes part of the substances around it. Once in a watery locale, its eternal endurance of riding on dust specks or blowing in the wind pays off and it becomes keenly sensitive and active.

How It Works

When an amoeba feels things bumping against its body, such as minuscule bacterium (its food source), it immediately sends a feeler out, breaching the membrane, to capture it.

These feelers (called “pseudopodia”) are kind of like backhoes with a scoop bucket. They emerge to capture the bacterium and then retract with it back into the amoeba’s body. A sack is formed around the yummy bacterium until digested. Once the nutrients are removed, the temporary stomach pouch, then containing only waste, is ejected by the pseudopodia. Even though it has no stomach, intestines, or bowel movements, the amoeba is extremely self-sufficient.

When food is plentiful and the amoeba eats to excess, it does not remain chubby for long. Instead, it divides in two, and an identical amoeba is born. An amoeba has no parents, yet, unless squashed, boiled, or dried out, an amoeba, in theory, can live forever. If eaten by a fish or ingested by a bird, the amoeba will outlast it several times over. An amoeba never grows old or ages in any way.

Friend or Foe?

There are thousands of different kinds of Amoebozoas, many of which inhabit our bodies without ill effect. A number are particularly dangerous and potential killers. The Naegleria amoeba lives in freshwater lakes where water temperatures exceed 80 degrees Fahrenheit. These enter through a swimmer’s nostrils or mouth and find their way to the brain. They feed on nerve endings and trigger headaches, stiff necks, and fevers within weeks. Hallucinations and abnormal behavior follow until deadly brain swelling results. It is unclear how long those particular amoebas can live, or if they also die, forfeiting their immortality by killing their hosts.

Are Amoebas Animals?

From the time of Aristotle (ca. 300 B.C.) until the late 1800s, all life was divided into two kingdoms, with everything classified as either animal or plant. In the late 1600s, scientist Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek urged the scientific community to add a third kingdom for unseen single-cell creatures that he “discovered” after perfecting magnifying lenses and ultimately inventing the first microscopes. He originally called these single-cell beings, including amoebas, “animalcules,” which are now classified as microorganisms. These animalcules were added to zoological classification in 1674, but they were categorized in either the plant or animal kingdom. The third kingdom of Protista, which is where amoebas are now placed, was made distinct in 1866 under the urging of biologist Ernst Haeckel. As an innovative scientist, Haeckel also proposed the idea that the evolution of an individual species could be observed by studying an organism’s changes during gestation. To demonstrate, he showed how a single-cell sperm and egg transformed from a fishlike embryo and then eventually developed into a human baby. Haeckel said a baby’s embryonic development was a mirror of our evolutionary path.

AMPHIVENA

Two-Headed Lizard-Bird

According to Greek mythology, this half-bird, part-reptilian creature had two heads of unequal sizes. Its larger head faced forward, while the smaller second head looked backward and grew from the tip of the amphivena’s whiplike tail. When the amphivena hatched from an egg, the little head had to awaken the oversized head from its embryonic state or else the creature would die. Both heads were fully functional, and each ate and drank independently as needed. It had two sharp talons for claws, a leathery snake skin, and feathers only on its wings. These creatures grew typically to about 6 inches, or the size of a sparrow, but with longer, hairless necks. Other witnesses claimed to observe amphivena that were 2½ feet tall. They took to cold climates well and were the last to hibernate and the first to reappear in spring. Many ancient writings described this creature as some sort of strange worm, or as a combination lizard-bird, a missing link between the two, which gave a harmless pinching sting similar to a flea. It was difficult to sneak up on these animals or capture them; each head took turns sleeping. They had eyes that literally turned off to get black as marbles or alternately glowed emerald bright and sparkled like mirrors.

Amphivenas’ hides were used in medicines to reduce “cold shivers.” If a pregnant woman crossed paths with an amphivena, it was common knowledge that she would probably miscarry. It was unknown whether this adverse event was caused by the amphivena itself, or from sheer fright after stepping on such an extraordinarily odd creature.

Were They Real?

In the 1570s, John Gorraeus, a French physician, tried to explain why references to the two-headed amphivena had appeared extensively in both ancient Greek and Roman books, though no living specimens could be found. He believed multiple-headed creatures were isolated incidents and mentioned a snake then recently born in Ceylon that had four heads. Gorraeus interrogated witnesses who described how each head of the snake faced north, south, east, or west, and no matter how it was turned, it would not rest until each darting tongue indicated the four points of a compass. More likely the amphivena could have been a hoop snake that lies with it head to its tail and is easily mistaken for a bicycle tire.

ANDEAN CONDOR

Nature’s Trash Man

The 4-foot-tall Andean condor is a lofty bird weighing over 30 pounds. According to the principles of aerodynamics and the laws of gravity, the bird is so bulky it should require a long runway before it is capable of achieving flight. Andean condors live in a range that spans the entire Southern Hemisphere. They prefer mountainous areas but are also found near oceans and even in deserts; they need regions where strong thermal-air currents allow them to stay airborne. Most condors are now concentrated along the west coast of South America.

Once airborne, a condor glides in wide circles, as high as 3 miles above the ground, sometimes not flapping its wings, and only shifting the end tips of its wing feathers for direction.

Waste-Removal Experts

Like all varieties of condors, the Andean condor is a vulture, with a black feathered body, white under its wings and tips, and a bald head. Male condors have white collar bands, and all have hooked, strong beaks designed to rip open the carcasses of dead animals. They can go for a few days without eating, but once they locate a fallen animal, they gorge until so stuffed they are barely able to obtain liftoff. In nature, vultures are the chief hazardous waste removers, eliminating the dead that would spread diseases and contaminate water supplies.

With their bald, featherless heads, condors wear a sort of permanent rubbery mask, which prevents oozing bacterium from infecting them. Throughout history, condors and all vultures were looked upon with disdain for their appetite of eating the dead, and more so for sensing death’s close approach. However, when considered as an effective recycler, doing a job that few find attractive or are as equipped for, the condor leads the animal kingdom’s sanitation patrol.

Life Cycle

Condors usually only lay one egg per year. They breed in July, and both male and female warm and guard the egg and take care that it does not fall from its rocky ledge. Since the nests usually lack soft bedding, tending the egg and not cracking it against the rocks until it hatches sixty days later is no easy matter. Both parents stay with the chick for another six months, teaching it all they know about being a vulture until it can keep up with the flock and circle to impressive heights. When the young condor turns five or six years old, it will choose a mate and remain faithful to it for its entire life. Some vulture couples have been together for over fifty years, and there are records of condors living for more than one hundred years.

Condors build nests as high as 15,000 feet above sea level and like to perch where they can simply jump off and be immediately in the wind streams.

—

Vultures can eat anthrax, botulism, and other deadly diseases without ill effect.

—

Plutarch, a first-century Greek historian, wrote about the vulture: “For it is a creature the least hurtful of any, pernicious neither to corn, fruit-tree, nor cattle; it preys only upon carrion, and never kills or hurts any living thing; and as for birds, it touches not them, though they are dead, as being of its own species, whereas eagles, owls, and hawks mangle and kill their own fellow-creatures.”

Mating for Life

In nature, monogamy is an anomaly rather than a rule. However, the black vulture is one creature that takes its “wedding vows” seriously and will even sometimes kill an unfaithful spouse. There are some other animals that breed with the same partner for long periods, many for life: anglerfish, bald eagles, barn owls, beavers, brolga cranes, condors, coyotes, gibbon apes, ospreys, pigeons, prairie voles, sandhill cranes, swans, and wolves.

ANGLERFISH

Deep-Sea Oddity

Nature can have a surrealist flair when fashioning some creatures. The anglerfish, a bottom-dwelling species found in the deepest oceans, would win any contest for the most innovative and perhaps the craziest of animal designs. It lives in the lightless environ of the ocean floor, as far as 1 mile deep, in regions known as the abyssal zone. Its range extends from the Arctic through the North Atlantic Ocean and down to Africa and even into the Mediterranean Sea. Anglerfish are also found in the Mariana Trench, the legendary abyss southeast of Japan.

The female anglerfish is always fishing for food. It has a thin, bony dorsal spine that extends from between its eyes and arches out in front of its mouth. The end of this permanent fishing rod is baited with a wad of tissue that is covered with a bioluminescent bacterium that glows and attracts prey—a tiny, electrically charged fishing lure. When small fish fall for it, the anglerfish snatches the curious. The anglerfish has a pail-sized mouth that snaps shut like a steel trap, capable of capturing fish twice its size. Its neon fishing lure also attracts mates, which are not eaten, but are enticed, perhaps, into accepting an even worse fate.

It’s a Woman’s World

In this dark ocean world, at least among anglerfish, the female is the only one who can fish for food. The male does not have the built-in fishing pole and must find a female that allows him to become a sort of pilot fish, at first trailing her wake and catching her scraps. Eventually, the male anglerfish physically attaches himself to the body of the female and hitches a ride by biting into her flesh. Soon thereafter, the male loses the ability to see or open his mouth, and in due course, all the male’s internal organs disappear, with the exception of his testes. By fusing to the female, the male then receives all his nutrients from her shared bloodstream. A dominant female anglerfish can have as many as a dozen of these freeloading males permanently attached as she swims, providing the day’s food for her collection of leeches. As for a benefit in reproduction, the female never has to go far to get one of her males to fertilize her eggs.

Life Cycle

Some anglerfish live in schools; others are solitary, though often they gather in the vicinity of underwater thermal vents, where a strange kaleidoscope of creatures exists. The superheated water reaches temperatures of over 500 degrees Fahrenheit, though heat dissipates rapidly in the surrounding near-freezing water to make it habitable. Anglerfish thrive in this nearly sci-fi environment and have been known to live for more than one hundred years.

The anglerfish’s lower jaw protrudes and looks similar to a gobbling Pac-Man video icon, though with horrifically sharp and jagged teeth. There are two hundred different species of anglerfish that grow in size from as little as 8 inches to over 3 feet.

Relationship Counseling

As human couples often do, animals in nature sometimes engage in what are called “symbiotic relationships.” There are three basic types: first is mutualism, when both parties benefit from each other’s company; second is commensalism, when one party is benefited while the other is neither harmed nor rewarded; and third is parasitism, when one gains all to the detriment of the other—and among humans, at least, this often leads to divorce. As for anglerfish, with its seemingly inequitable arrangement where the females do the bulk of the work, its relationship actually qualifies as a sort of dysfunctional mutualism. For her labors, the anglerfish has an unbreakable hold over a harem of lovers who are always at her beck and call, but with an assurance that her eggs will be fertilized and her lineage survive.

ANTS

Nine Trillion Strong

Ants lack ears and lungs. They hear by vibrations and breathe through holes in their bodies. They use chemical scents called “pheromones” to communicate and identify other members of their colony, as well as a way to mark a trail once they find food, telling others where to go and how to bring it back to the nest. An ant has the power to lift an object more than forty times its body weight, such that if it were the size of a human, an ant could pick up a city bus and carry it a mile. All ants in a colony, with the exception of the queen, are considered expendable and are sacrificed to save the nest without hesitation. Soldier ants are so tough, they will join forces and use their heads as a barricade to plug the colony entrance. When a worker returns, it knows how to knock or bang on the heads of the solider ants in such a way as to gain entry.

When ants form a line to carry crumbs, they are reluctant to pass their loads to other ants and usually insist on taking them back to the nest themselves. They persist at finishing whatever job is assigned. When ants collect seeds or grains, they are careful not to bring them back to the nest if the seeds have the potential to germinate, since once sprouted, they could destroy the ants’ underground tunnels and chambers. Specialist ants take the responsibility of temporarily arresting seed germination by eating only a certain portion of a seed, then removing the harder part of it from the nest where it is dispersed and then blooms. In this way, ants are efficient forestry managers. If any of their stored food gets wet, ants take their inventories back aboveground and dry them off before restocking.

Ant Society

There are more than 12,000 species of ants found all over the world—with the exception of Antarctica, Iceland, and Greenland. They live in rock, sand, soil, trees, wood, and in man-made items like airplanes, cars, and electrical panels, as well as, reportedly, even inside of living people. There are stories of how ants can crawl inside a sleeping picnicker’s ear and form a colony in the brain, eventually killing their host. However, due to the anatomy of our ear canals, protected with earwax, such a feat would be difficult even for the most persistent ant.

For every one human alive today, there are 1.5 million ants crawling around at this very moment—approximately 9 trillion total ants. Since there are so many types of ants, certain habits vary, but all ants are social animals and can survive only as a colony. Thief ants are the smallest ant, no bigger than 1/16 inch, while sausage ants (named for their overbloated abdomens) are the biggest, growing to over 2 inches. The largest colony of ants belongs to the Argentine ants, with one colony stretching for 3,700 miles.

Ants come in three varieties: the queen; winged male soldiers, which also might be assigned as mates for the queen; and worker ants, which are all females. Although particular habits of ant species differ—some colonies, for example, have more than one queen—ant society is broken down into castes, wherein individual ants are assigned very specific roles and duties. An ant rarely has a chance to change its status within the colony and must perform the function it was given for the remainder of its life. If ants attack another colony and win, they transport the enemy’s eggs as war booty back to their nest, hatch them, and make the captured ants their slaves. A queen, once so enthroned, has only one job—lay eggs. She can produce one million eggs in her typically three-year life span. Males allowed to mate with the queen die shortly after. When the queen herself dies, the colony is doomed, and all workers and soldiers perish within a few months. Some queen ants have incredibly long lives—over thirty years—while a typical worker ant lives for about three months.

You’ll never see an ant out in the rain—they know when inclement weather is approaching before a cloud appears in the sky.

Art of Ant War

Some ants plan attacks on neighboring colonies and use different tactics to achieve victory. The Argentina ants, with supersize colonies, will move through a territory they wish to acquire, laying waste to more than a million enemy ants within one day. Other ants have been known to encircle an adversary’s nest and simply wait, letting no ants in or out. When the colony under siege loses its wits and starts running around in a disorganized frenzy, the attacking ants move in for an easy win.

Farmer Ants

Fossil evidence suggests that ants flourished for 150 million years and were underfoot when dinosaurs ruled. They also have practiced a form of farming for 70 million years, long before people thought plant cultivation was the most reliable way to obtain food. Ants plant seeds of various plants that have sweet sap or contain nutrients specialized to their diet. They can also produce chemicals to ward off fungus and kill mold to protect their crops. In addition, ants designated to be farmers are assigned to a variety of fertilizing duties, and they know how to use their own waste or manure from other animals, which is spread around to nourish seedlings. Ants even employ sap-sucking insects and aphids, carrying them on their backs to harvest their crops. After the aphids suck the plants’ fluid, the ants eat them.

Ant-Lion

Ancient books on natural history describe a prehistoric species of large antlike insect that had mated with a lion. It was supposedly the size of a dog. It had the face of a lion, but all other body parts resembled that of an ant. The females of the species ate grain, while the males ate meat. It was reasoned that this creature disappeared due to its differing appetites, which never allowed for a harmonious union.

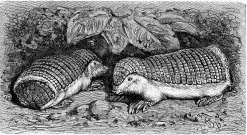

ARMADILLO

“The Little Armored One”

There are 20 different types of armadillos—ranging in length from only 1 foot to more than 5 feet long, and weighing from 8 ounces to 130 pounds. They are found naturally in the southern parts of North America and throughout Central America and South America; most prefer warm weather since they freeze easily. This animal descended from an order of mammals of which anteaters and sloths are fellow members. Armadillos live in burrows and are equipped with sturdy, sharp digging claws designed to hunt for their food of insects, ants, and termites. They sleep most of the time and only rouse at sunrise and again at dusk.

The shell is made of bones and a hornlike material that is divided into flexible sections, which if necessary can enable it to form into an almost perfect sphere. The armor also allows the armadillo to escape into thorny patches to evade predators. It also defends itself by confusing enemies with a sudden leap; when an armadillo gets frightened, it suddenly jumps 2 feet off the ground before scurrying away. Some armadillos live alone; others live in pairs or in arrangements of a few, though they usually only come to gather in cold weather so they can share body heat inside burrows.

Armadillos often are killed while crossing roads. Instead of lying flat when they see headlights approaching, they jump up, just high enough to reach the car fender. They are also one of the few animals that get leprosy, a disease that eats away at the flesh. Armadillos are unusually susceptible to this human disease due to their lower-than-normal body temperature. Even so, armadillos typically live for about four years, but some luckier individuals have reached the age of twenty years.

The armadillo’s distinctive protection of body armor gave it its name, which is Spanish for “the little armored one.”

Armor Patrol

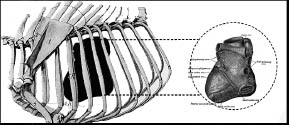

Porcupines, although not at all related to armadillos (they instead rank as the third-largest rodent), also developed a form of armor. A porcupine’s elongated hairs are encased in keratin, the protein that makes our fingernails hard. Its 6-inch quills are barbed and release upon contact, but it cannot shoot them at will. By way of contrast, the armadillo’s armor is made of dermal bone, the same type of bone found in human skulls.

The most tanklike body armor of all time belonged to the ankylosaurus. It was a squat, 35-foot-long dinosaur, with a clubbed tail. It had a back or shell made of hard bony plates, topped with spikes. The armor bones were pleated in a way similar to an armadillo’s shell and could withstand a chomp from a T. rex, though the ankylosaurus could not roll into a ball. It became extinct sixty-five million years ago. Soon after, relatively speaking, about sixty million years ago, the new and improved model, the armadillo, appeared, so it is nearly as old as dinosaurs.

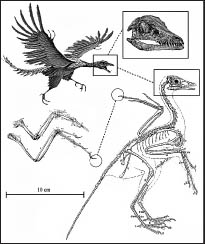

ARCHAEOPTERYX

First Bird?

During the days of dinosaurs, there weren’t many creatures that we would recognize as birds. Most creatures were reptilian, though one well-persevered 150-million-year-old fossil of a birdlike beast, the archaeopteryx, shows how the transition from earthbound to sky-roaming creature might have taken place. The archaeopteryx was small, only as tall as a modern-day crow. It had teeth and three claws on the outer part of its wings, features that birds today do not have. Its bones were hollow, making it light enough to take to the air—though its limb structure was not developed for long flights or high-altitude soaring. It had a hornlike bill and was most likely an omnivore. By strict definition, the archaeopteryx is not classifiable as a bird, according to most scientists, yet it can be appreciated for being the earliest known animal to achieve flight.

What Makes a Feather Fly?

For anything to fly, it must adhere to the four basic principles of aerodynamics and compensate for lift, thrust, weight, and drag. Simply, a bird’s feathers (and wing shape) do most of the calculations needed to achieve flight. Like fingernails (and animal claws and lizard scales), bird feathers are made from the protein keratin. Birds usually have at least three types of feathers: interior down feathers, which are fluffy and aid in insulation; filoplumes or sensory feathers, which are primarily only a stem with a tuft of fibers on the end; and contour feathers, which are responsible for flight. Although feathers come in many shapes, lengths, and designs, flight is achieved as rows of tightly arranged feathers provide lift and thrust. Feathers are symmetrical, with an identical feather found in an equal place on the opposite wing. However, it is the complete wing structure that determines if the bird must be a constant flapper or is able to glide.

ASPIDOCHELONE

Legendary Living Island

Early sailors who returned to tell tales of their adventures at sea frequently mentioned sightings of a giant creature that was as big as an island. The fabled beast was exceedingly cunning and deceived the unwary by camouflaging itself as a small outcropping of rocks. A legend popular in ancient Greece described how sailors encountered the monster in waters far beyond the Strait of Gibraltar or in the deep oceans. These sailors navigated their ship close to what appeared to be a sturdy island and anchored. Eager to stretch their legs on land, the crew disembarked and lit fires on the beach. As the fires blazed, the entire island began to shudder when the heat suddenly aroused the sleeping beast into a crazed frenzy. The aspidochelone then latched on to the ship and pulled it and all the men down to the bottom of the sea.

Though some speculated it could have been a whale, the aspidochelone is thought to be a type of monster turtle. Those who claimed to have seen it (and survived) said it had a hard, stony hunched back similar to an enormous snapping turtle shell. It waited at the surface, remaining stationary for days at a time, appearing to ships in the distance as a haven to rest or gather supplies. The aspidochelone was so artful, it even dredged up sand from the ocean floor and made itself appear as a landmass with tranquil beaches.

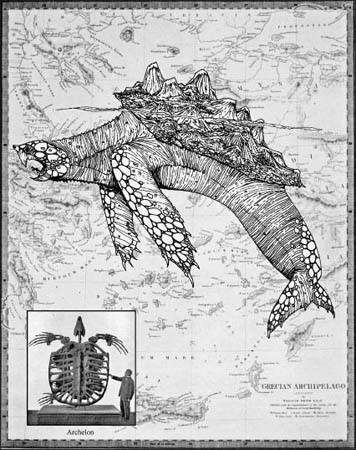

Was It Real?

Today the largest turtle, the leatherback sea turtle, can grow to 9 feet, but enormous specimens have emerged from the fossil record, suggesting it’s not impossible some living relic was encountered. There was a primitive giant turtle called an archelon. It was immense as far as turtles are concerned, measuring 13 feet long and about 16 feet wide. This oversize turtle likely disappeared sixty-five million years ago and roamed the ocean that covered parts of North America. Another prehistoric animal, a whale named Basilosaurus, was far larger, reaching a length of 60 feet, but this creature was (in all likelihood) extinct long before the earliest humans took to the sea in boats.

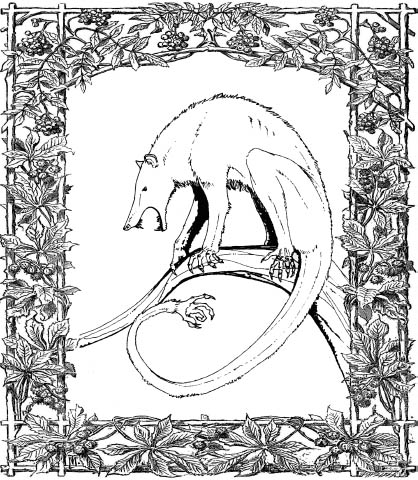

AYE-AYE

Knock, Knock, Who’s There?

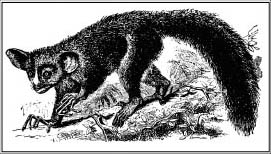

The aye-aye is a rain forest tree dweller that forages at night and rarely ventures far from its leafy seclusion. Native to the biologically diverse island of Madagascar, located off the southeast coast of Africa, the aye-aye is a primate (thus related to chimps and humans) that looks more like a rodent—with big eyes, bone-thin fingers, and a fluffy tail that is longer than its 15-inch body. It also uses a unique method to get food.

With its pointy ears pressed to a tree, an aye-aye listens for insect activity inside or for a hollow sound. After gnawing a small hole at that spot, the aye-aye inserts its middle finger into the gap to gather its feast. This is easy for the aye-aye since its middle finger is three times the length of its other fingers.

Are They Evil?

Due to the aye-aye’s outrageous appearance and physical oddness, many native peoples believed seeing one would bring instant bad luck. According to legend, the aye-aye was the reason why some people died during the night in their sleep, for the nocturnal animal would creep into huts and pierce sleepers’ hearts using its long middle finger like a knife. Because of this superstition, aye-ayes were killed on sight, historically. Now there are laws to protect them. Although their numbers are difficult to calculate, it’s estimated that fewer than 10,000 aye-ayes remain in the wild. When left alone, an aye-aye can live for about ten years.

By tapping its knuckles on a tree, the aye-aye finds its favorite food of grubs and insects that hide under bark.

AXOLOTL

“Mexican Water Monster”

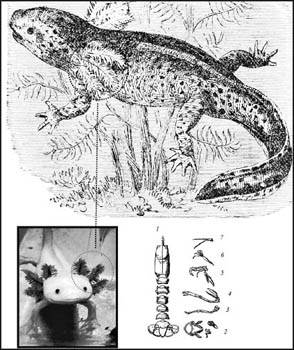

From the prehistoric subterranean lakes and caverns that once swirled in darkness under Mexico City, and from the high-altitude Lake Xochimilco of central Mexico (now drained), a special type of tiger salamander emerged. The axolotl is unlike other salamanders that metamorphose from egg to tadpolelike larvae and then to a fully formed land-dwelling amphibious adult. Instead, this creature halts development perpetually at the larvae stage, unable to live terrestrially for long. Called everything from a “walking fish” to “Mexican water monster,” it averages 6 to 9 inches in length (though it can grow to 1½ feet) and weighs less than ½ pound.

Even though the axolotl has lungs, it breathes through its gills and skin. In addition, it has unique regenerating properties that allow it to grow back lost limbs or parts of its tail at will. In contrast to many creatures that modified and evolved in a forward path, the axolotl is an example of an animal that devolved. At one time, these salamanders lived on land and in water like frogs, but for reasons unknown (though presumably it found an advantageous niche back in the water), the axolotl returned to an aquatic existence. Unfortunately, axolotls are nearly extinct in the wild. As pets, sold as wooper roopers, they survive in freshwater tanks, and if fed a steady diet of worms and mollusks, they can live for an astounding ten to fifteen years.

The axolotl has a distinctly round, grotesquely cartoonish face with six feathery antennae-looking feelers, which are actually gills, protruding from its neck.

De-evolved vs. Re-evolved

It is not fully understood why some animals revert anatomically to an earlier evolutionary state. From a genetic standpoint, a genome can switch off or on as a result of a variety of factors. In all animals, genes that are not in use can lie dormant for about six million years, yet still carry the overall genetic makeup of the species. It is assumed that if the gene is not switched on within ten million years, then its functionality will be lost. In theory, dolphins could regrow legs, and humans might be able to grow a tail.