LAGARFLJÓT WORM

Glacier Eater

A giant worm lives in a lake in the eastern region of Iceland, according to local folklore. It was first observed in A.D. 1345 and has been seen periodically through the twentieth century. More than 300 feet in length, it coils near the shoreline and only rarely slithers at the surface. Even though it has sharp teeth and can emit a foul gas, it seems to be a herbivore, since it is not known to attack animals or plague human populations in the vicinity. It is a thin lake monster, only about as thick as a man’s thigh, and is said to have both gills and lungs, able to live underwater or on land. Many consider it as an omen that something momentous, either good or bad, is about to happen whenever it does make an appearance. The colossal creature survives in the Lögurinn Lake, which is pure but murky from silt deposits and erosion. The lake is a basin for water flowing from melted glaciers carried by the Lagarfljót River. Even if an entire class on a school trip recently reported observing it slithering upstream, taking ten minutes to pass, the “worm” is likely grasses and weeds whorled together by currents, or optical illusions caused by bursts of methane gas, which is found in high concentrations on the lake bottom.

What Is It?

The Lagarfljót worm is often suggested to be a giant eel. There are nearly twenty known species of freshwater eels, though none of such gargantuan size, even if some marine types reach 8 feet in length. An eel is mostly tail, with the majority of its organs located close to its head. Under unique conditions, an eel’s tail can grow to unlimited lengths.

Lake Monsters

Among creatures unexplained by science, lake-dwelling beasts are the most common, with more than one hundred various creatures located worldwide. The worm of Iceland is unlike the long-necked lake monsters, such as the Loch Ness creature. The Ogopogo of Lake Okanagan, British Columbia, is another fabled worm monster about 15 feet long, with fins on its head and body that when swimming resemble limbs. Champ of Lake Champlain, New York, allegedly is about 30 feet long, with no visible head, though it has humps along its back.

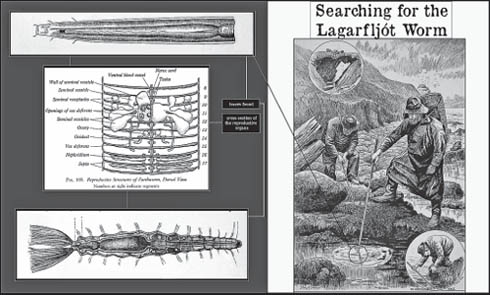

LANTERN SHARK

Glow-in-the-Dark Shark

The lantern shark is one of the smallest sharks known to exist and grows to no bigger than the length of your arm. It swims mostly throughout the Atlantic Ocean, although it is sometimes seen in the Pacific Ocean near Japan and off the coast of Australia. Its favorite food is fish eggs.

It produces a hormone and chemical called “luciferin” in its belly that reacts with oxygen to create a blue-green light, similar to glow-in-the-dark sticks. This makes it blend in with the natural light in the ocean and go undetected by larger fish. Among living things, the production of a cold light source, which does not give off much heat, is known as “bioluminescence.” Sailors once thought the shark’s strange light was from ghostly sea lizards that feasted at night on souls lost at sea. In fact, lantern sharks seem to gather near hydrothermal vents, hotspots in the ocean where water is heated from underwater volcanoes or from shifting tectonic plates.

The lantern shark has developed a counterintuitive camouflage technique, employing light as a means to deceive and confuse would-be predators.

—

Samuel Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner alludes to creatures similar to the lantern shark:

Yea, slimy things did crawl with legs

Upon the slimy sea.

About, about, in reel and rout

The death-fires danced at night;

The water, like a witch’s oils,

Burnt green, and blue and white.

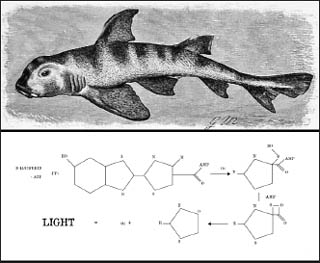

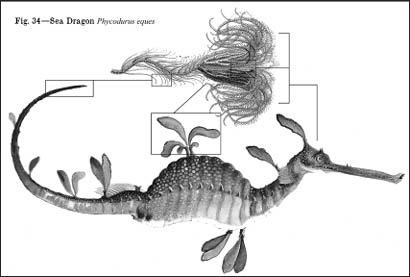

LEAFY SEA DRAGON

Master of Camouflage

Looking like seaweed can have its advantages, especially if you are a small, fragile seahorse living among the rough-and-tumble reefs along Australia’s southern and western coastline. Leafy sea dragons are covered with body protrusions that appear nearly identical to leaves; if it remains motionless among a patch of seaweed, it is practically impossible to spot. It even found a way to propel itself in a slow-motion manner, resembling a floating weed, by having only tiny movable fins on its head and another dorsal fin near its tail.

What Color Is Your Mood?

This seahorse grows from 8 to 18 inches and eats lice, plankton, shrimp, and small fish that it catches easily with a long, dragonlike snout. Predators or prey can rarely see it, not only because it looks like a plant, but also because it has the ability to change color at will to match the hues of its aquatic environment. A certain diet can affect color changes, but the leafy sea dragon can also turn a different shade when stressed, ranging from brown, pale pink, blue, green-yellow, and reddish. It chooses different color combinations when feeling content or for mating, and it can even make itself transparent when, perhaps, it does not want to be bothered by anything.

The downside of hiding in plain sight and a go-with-the-flow lifestyle occurs when a sudden wave flushes a seahorse from the reef, making it impossible for it to return to the habitat where it is most suited. Unlike other seahorses that have gripping curled tails, the leafy sea dragon cannot anchor itself during turbulent conditions, and it is either blown out to sea or washed ashore. Leafy sea dragons, if very lucky, live in the ocean no more than three to five years.

Tricks of Camouflage

Some animals have fur that changes color depending upon the season. For example, the arctic fox sheds its summertime darker coat to one of snow white as winter sets in. Environmental temperature changes and shortening of daylight trigger an animal’s hormones to help make its natural camouflage more adaptive. For fish, reptiles, and color-changing amphibians, many have cells called “chromatophores,” each containing a certain color pigment. Another master of marine camouflage, the cuttlefish, has minuscule muscles surrounding each of its chromatophore cells. It can willfully constrict the muscles attached to the color cell of its choosing, changing its skin the way an artist squeezes paint from a tube.

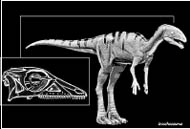

LESOTHOSAURUS

Chicken Dinosaur

This two-legged little dinosaur looked like a featherless chicken scurrying about, and, according to its hipped-bone structure, it was probably an early ancestor of several bird species. It was about 3 feet tall and ran on two legs. It usually traveled in large packs or flocks, darting about from boulder to shadow in a frenzied manner. Its nervous and swift-footed disposition was a necessary adaptation since it was a bite-sized nugget to many of the large carnivorous dinosaurs that were about. Lesothosaurus was a herbivore that became extinct about sixty-five million years ago, when it is theorized that asteroid impacts darkened the sky and polluted the earth’s atmosphere for at least a decade, likely killing off the lesothosaurus’s favorite plants.

LEUCROTA

Speed Demon

This mythical hybrid beast lived in India. Its badgerlike head had a wide mouth that could open from ear to ear like the Cheshire cat’s. It was as long as a donkey but the height of a dog, with deer legs and a lion’s tail. Leucrotas lacked teeth and instead had hard, bony-ridged planks that served as jaws to mash and saw its prey into pieces.

The leucrota reportedly plagued humans’ attempts to domesticate animals and clear forests, both necessary for early agriculture. Second-century Roman writer Claudius Aelianus claimed to have seen the beast during his travels and related how it had the ability to imitate human speech, including the inflection and accent of the speaker. In one incident, woodcutters were clearing an area while leucrotas hid secretively in the brush. The beasts listened to the men for many hours. By evening, the leucrotas moved off some distance and began calling out a man’s name. As the woodcutter followed, they backed away, leading him deeper into the forest until he was alone, at which point the leucrotas devoured him.

What Was It?

There is, of course, no animal with planked teeth that can speak in a human voice. However, a clue found in ancient records related to the leucrota’s speed, said to be the quickest among beasts, which matches that of the cheetah. A yawning cheetah appears to have a wide mouth, and the black fur marks under its eyes—like the cheek smudges worn by athletes to cut down glare—gives it a different look than most cats. Cheetahs are the fastest land mammal, reaching 60 miles per hour. They are daytime hunters, and, for this reason, they need speed to survive, rather than stealth like most feline predators. Cheetahs are found in Africa and southern Asia and might have been the leucrotas the ancients feared. However, the cheetah’s body is vulnerable, designed as it is for speed and not for tangling with lumberjacks. In fact, most of the game cheetahs kill is rapidly absconded by hyenas and lions, which the small cat relinquishes without a fight. Cheetahs live for about twelve years.

To trick hunting dogs, leucrotas mimicked the sound of a man vomiting, and when the dogs went toward it, thinking their master was in distress, the beasts ate the dogs. The leucrota was devilishly difficult to capture and thought to be the fastest-running animal of all.

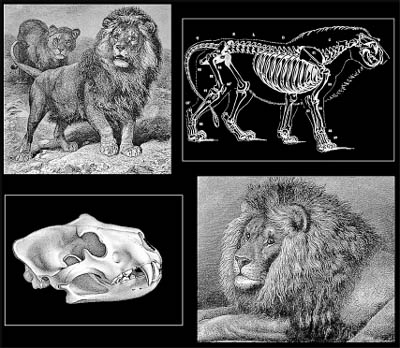

LION

King Carnivore

Prehistoric ancestors of the modern lion first appeared in Africa more than seven hundred fifty thousand years ago. Various subspecies spread throughout Europe, Asia, and North America. However, by the end of the last Ice Age, around ten thousand years ago, most of the prehistoric strains, including the European cave lion and the North American lion, had disappeared. During those earlier millennia, the lions were adaptive predators, reaching a worldwide sprawl that was comparable among animals to that of primitive man. If not always the apex predator in the days of saber-toothed tigers and giant bears, the lion was indeed formidable and feared as a powerful and aggressive beast. The Northern American lion, the biggest lion of all time, grew to 11 feet and weighed 700 pounds, while the modern version is still massive at 6 feet, topping the scales at 500 pounds. Now, lions live naturally only in sub-Saharan Africa and in parts of India.

Lioness Club

Most predatory cats are solitary hunters, but the lions’ success, in part, rests on their intricate social network and group hunting. Lions live in family units, called “prides,” consisting of ten to twenty females and their cubs, under the dominance of one or two males. The lionesses hunt more often than the males and use ambush methods, sometimes employing decoys to drive prey to where other lions are waiting. They even learn to communicate in the field, using the tufts of hair on the end of their tails as pointers, sort of as silent walkie-talkies to give directions and information on the progress of the prey. The male lions are responsible for marking territory, up to 100 square miles, with the scent of their urine or by physically marking trees and keeping away intruders. For this, even though the lionesses usually acquire the food, the males are given the right to eat first. Sometimes, however, the females clamp down on the catch and refuse to give the male his traditional first bite. Mealtimes are not relaxing for the pride, as fights, clawing, and even death occur over dinner.

Hairdos Only Last So Long

The males have distinctive manes, and usually the ones with the thickest and fullest hair are considered most attractive to females. The male lions’ reign is in constant jeopardy, challenged frequently by young males. Their rule of the pride usually never lasts more than a few years, at best, until they are driven out or killed in battle by a stronger, younger lion, regardless of how good-looking their manes might be. Most of the pride consists of related females, male and female cubs, and older sisters and aunts. The young male lions are driven away at around three years, and it is not uncommon for brother lions to hunt together for life, until they can together usurp a lion of another pride. The old dethroned lions turn to a life as solitary hunters and usually die shortly after; as they grow feeble and old then are even attacked by predators, especially hyenas.

The lionesses enjoy lifelong stability, or at least more so than males, although they might suffer the murder of their cubs when a new ruling lion takes over.

What’s for Dinner?

Lions have strong front legs jointed in such a way that they can catch prey by the neck and clutch it in a sort of headlock. They flip it over to break the animal’s neck. They also frequently kill their prey by suffocation and merely enclose the animal’s mouth or snout in their powerful jaws until it stops breathing. Sometimes they go for the jugular vein, but, in all cases, they do not like to struggle with their meal or fight with it for too long. Leaping on a running animal’s back and going for a death-defying ride is the most dramatic but the least favorite method of acquiring meals.

When in the midst of a hunt, the lioness jumps horizontally to over 30 feet, and leaps as high as 12 feet into the air. As for speed, lions run no faster than 30 miles per hour and only for a distance of less than 50 yards before becoming winded. Many animals, once cornered by a lion, run like mad, while others freeze as if hypnotized by the lion’s gaze.

The lion has sharp 1½-inch-long claws, which are retractable and spring open with the swiftness of switchblades. The lion’s teeth include front incisors that are 5 inches long. Lions can eat 40 pounds of meat at one time, and then usually do not eat again for four or five days. After these feasts, lions often sleep for eighteen to twenty hours each day.

Last Roar

Lion cubs have the highest mortality rate, compared to other large cats, with fewer than two in ten surviving the first year. Many die from teething, an apparently painful process, as their large teeth move into place. While teething the young are unable to eat. They are also the last in line at all meals, and when food is scarce, many frequently starve, or, as mentioned earlier, they are eliminated by a new male that takes over a pride. In the wild, lions live for about twelve years. The elderly or infirm are shunned, and themselves fall prey to predators when unable to keep up with the pride or they are cast out from the group.

A number of old lions become man-eaters, finding humans, which they normally avoided, as easier prey. In 2004, an elderly lion, nicknamed the “Cunning One,” was blamed for eating forty-three people in a village in Zambia. Tanzania reports at least one hundred human deaths at the jaws of mostly older lions each year.

—

Legends say the lion uses some sort of telepathy that calms its prey, telling it that its death will be fast and less painful if not resisted. More likely, though, is that the weaker animal is immobile from shock or counting on some miracle of camouflage not to be noticed.

—

Lions are strong, but they could be called lazy, preferring to lounge for nearly a week, or more, in between meals.

—

A lion’s roar is truly bloodcurdling and so powerful that its exhale is strong enough to turn a cloud of dust into a mini-tornado. The roar is audible for nearly 3 miles.

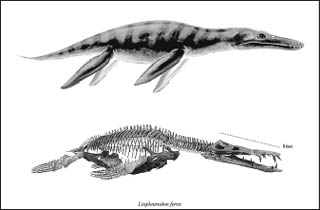

LIOPLEURODON

Mighty Marine Marauder

This aquatic reptile once dominated the oceans that covered Europe about 150 million years ago. Its skull was the size of a tall man, over 6 feet long, and it had a long snout filled with shredding teeth. It had paddle arms for propulsion and an enormous bulging body, which extended another 30 feet to its tail.

It liked to lie in wait, camouflaged in green-algae-covered lagoons, and lunge from the water to munch on shore-feeding dinosaurs. However, even though it had to breathe air, its hugeness made it a prisoner of the sea. It was too cumbersome to leave the water, or it would be beached and suffocate under its own tremendous bulk. As voluminous as it was, when hunting in water, the liopleurodon swam swiftly and caught prey with rapid surprise attacks. It had developed pulsating nostrils that were highly developed to detect scents even underwater. The last liopleurodon disappeared along with all the great dinosaurs, around sixty-five million years ago.

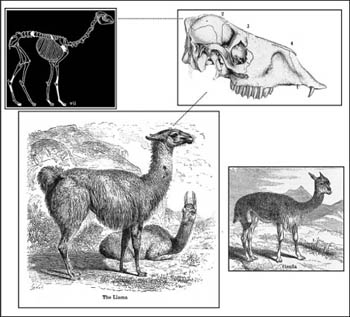

LLAMA

Andean Spitballer

Llamas once roamed the North American plains, but when the last Ice Age began to subside about ten thousand years ago, they migrated to the Andes Mountains of South America and made that area their exclusive natural range. It is hard to know how the original llamas behaved since like the alpaca, a smaller llama relative, the animals were domesticated by the Incas. An undomesticated relation of both llamas and alpacas is another high-altitude cameliod beast called a “vicuña”; all these animals have similar traits and are famous for their unusual ability to spit a considerable distance, with a fair degree of accuracy.

The High Life

Few animals have successfully adapted to living in altitudes as high as planes fly, where air is nearly 50 percent thinner than it is at sea level. Llamas have large concentrations of oxygen-carrying proteins in their hemoglobin, which make them capable of living at heights of 13,000 feet. Llamas are plant-eating herd animals that prefer to group among related family members. They usually have one male as leader of the herd, but this status changes easily; they do not like to get into serious confrontations among their own kind, although they do bite each other when an argument arises over vying for a mating partner. Female llamas give birth to one baby at a time after an eleven- to twelve-month gestation.

Llamas grow to about 4 feet tall at shoulder height and reach 6 feet to the top of their head. They can weigh about 280 pounds.

The Incas’ Llama

The natives of Peru and the Andes first domesticated llamas over four thousand years ago. There were no horses or donkeys, and the llama became the only means of transportation moving cargo. During the Incas’ reign, llama and vicuñas were prized for their wool. The hairs of the animals were considered so valuable that laws permitted only royalty to wear vicuña wool garments. The llama was such a valuable creature to the people of the high countries that the dead often had llama statuettes buried beside them in their graves, supposedly to help in the afterlife.

Spit Speech

Llama spit is partially digested food it draws up from one of its four stomachs. Since llamas can regurgitate easily and rechew food called “cud” in their mouths, they have a wad always ready for disposal. When they do it, the sound is more like a cough than a spit. The spit’s intensity ranges from a large amount of nauseatingly foul-smelling goo to as little as a small spray.

In general, a llama spits to convey annoyance. How angry it is determines how down deep in its stomach a llama reaches, knowing that hocking up spit from its digestive tract has the most atrociously putrid smell and taste, thus making a stronger statement. Happier llamas can hum to each other; they communicate alerts to the herd by making a braying signal.

Llamas give birth only from 8 A.M. to noon, when it is the warmest in the high mountains. During and after labor, other females will gather around the new mother with her calf and form a circle to block the wind and protect the newborn from predators.

—

Llamas spit to keep younger members of the herd in line, and females might spit at males that are being too aggressive when they wish to be left alone.

—

In the wild, leopards, cougars, and condors (when llamas are very young, old, or ill) are their natural enemies. Llamas live on average for about twenty-five to thirty years, but some have lived for as long as forty years.

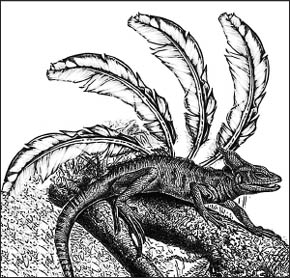

LONGISQUAMA

Evolutionary Enigma

The first flying vertebrates appeared about 225 million years ago. One lizard from that era seemed to be caught in the cross fire of evolution and apparently had no wings, but it did feature a series of long feathers that grew out of its spine. This would appear to be a futile adaptation that would only serve to knock it down sideways in a strong wind. Perhaps its plumage served as a camouflage to make it look like a walking fern plant? The spine feathers might have been a deterrent and offered a mouthful of gagging fluff to whatever predator that wanted to eat it. The longisquama was unusually small for dinosaur times, at only 6 inches long. Nevertheless, what appear as feathers in fossils might be elongated reptile scales, subsequently not making the odd lizard a precursor of flying animals after all, but rather a mysterious evolutionary dead end.

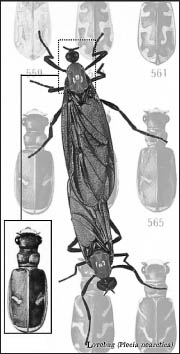

LOVEBUGS

Insect Honeymooners

Swarms of attached insects invade the Gulf Coast regions of the United States and throughout Central America each May and again in September. They fly as couples in a meandering way, joined at the abdomen. The insects emerge in such numbers that they darken the sky, as if it is raining black soot. More than several hundred thousand can fill an air space no larger than a football field, all the way from the ground to more than 1,400 feet up into the sky. They do not bite or sting but do have an acidic blood that corrodes paints, clogs car radiators, and smears windshields in a mass as thick as glue.

The lovebug is a member of the march fly family, which contains about 700 species, and spends most of its early stage of development undetected, living inconspicuously in grasses and among marsh reeds. It has a narrow black body with a red middle part below the head, or thorax. Females are about ⅓ inch long, while the males are smaller, measuring ¼ inch in length. Although both flap wings during flight, the females do most of the work and face forward while the male looks in the opposite direction, seemingly going along for a ride he cannot escape.

Locked in Embrace

Lovebugs go through a complete metamorphosis, from egg, larva, pupa, and adult. The larva stage lasts the longest, from around six to eight months, hatching from the three hundred or so eggs laid under decaying vegetation. The pupa, or miniature adult phase, extends for about a week. However, when temperatures reach more than 68 degrees and the days have more light, the adult males climb to the top of reeds and wait for the females, which soon come forward in swarms.

Buxom Bugs

The larger the female, the more desirable she is to the males. The swarming females are gripped by the tinier males, and held on to with all their might, until the males can manage to attach themselves to the females’ abdomens. The male does this to deposit sperm into a female’s peculiar reservoir and fertilize her eggs. If a pair mates toward evening, they wait as a couple until daylight before flying away attached. They may disengage and mate again, but most couples stay irrevocably conjoined for a few days. The adult female will separate only when she is ready to deposit her eggs, but afterward, she dies within seventy-two hours. The male lives a bit longer, for approximately ninety-two hours, before sheer exhaustion ends his brief but passionate existence. Lovebugs have few natural predators due to their acidic flavor. Not many birds think of them as food; even most spiders pass on a meal of lovebugs.

The lovebug is so odd, most think this natural phenomenon is a result of a bioexperiment gone bad.

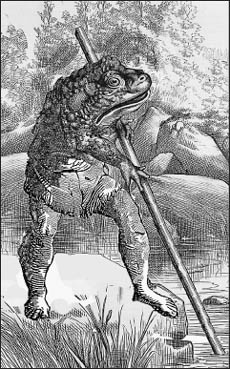

LOVELAND FROG

Creature from the Black Lagoon

In the dark rivers of central Ohio in the United States, according to local folklore, there lives a 3-foot-long creature that walks upright, has the skin of a frog, and bears facial features similar to a human’s. Its face is slightly distorted, however, and has a wide mouth without lips, though its eyes and nose are humanlike. It has wrinkles, skin folds, or hardened ridges instead of hair. It also has use of its hands since it was spotted once carrying a portion of a steel pipe. It lifted the metal bar high and was strong enough to strike it against a rock to cause sparks. It lives primarily in water, but probably is amphibious, as it is believed to be the cause of small and unexplained campfires found along riverbanks, where it tries to warm itself during cold spells. It has never been seen in winter, when it’s suspected to be hibernating. In the spring and summer, it emits a strong odor similar to almonds, which is assumed to be a scent it uses to mark trails or perhaps to attract others of its species during mating season. It is extremely shy and does not seem to want to harm anyone, and it has been frequently shot at when encountered by chance. No specimens have been captured alive, and no carcass of the Loveland frog has been found, though many believe it still exists.

Lizard People

World mythology has numerous references to reptilian humanoids. The earliest stories of creation found in Babylonian texts describe a race of ancient aliens that came to colonize the earth. In artwork, these beings are depicted as humans with reptilelike features. The Chinese have a similar mythology depicting “Dragon Kings,” humans with reptile bodies. In Native American folklore, oral histories describe how a meteorite, or some huge celestial object, fell, which caused many to seek refuge underground, living in a labyrinth of tunnels. In South Carolina, there are reports of a “Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp,” who is 7 feet tall and lives in drainage pipes and lagoons. Proponents of the Loveland frog, and those who claim to have sighted other humanoid reptiles, theorize that such creatures were products of genetic material transported by meteorites. Others say these creatures are castaways from the ancient aliens and were abandoned when their race left the planet, considering the earth inhospitable. It’s said they now live in tunnels and sewers scattered around the world.