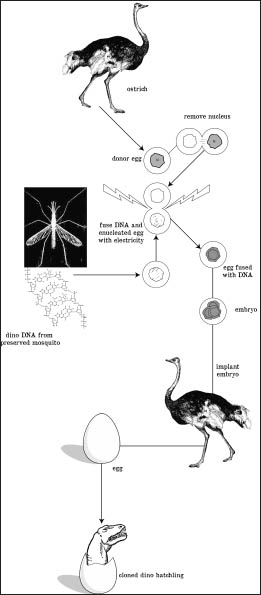

THRASHER

Nature’s iPod

Thrashers are North American songbirds possessing the world’s largest repertoire—they know how to sing as many as three thousand different tunes. Brown thrashers are found in Canada and the United States, predominately east of the Rocky Mountains during the summer; they migrate to the southern United States for winter. A flasher is not the flashiest of feathered birds, with a light reddish-brown colored body and wings, and a white-speckled and black-striped breast. This drab color allows it to remain concealed while it sings among hedges and undergrowth. It has an above-average height for a perching bird, at about 11 inches, and a wingspan of 1 foot. Its beak is dull, and it has yellow eyes with large black pupils. Some of the thrasher’s notes, chords, and musical phrasing are as complex as many masterpieces of classical music; its ability to sing puts it at the top of the charts when measured by the complexity of its vocalization. One of the great tricks of the brown thrasher is its ability to mimic other birds, and it has the ability to keep learning new songs its entire life.

Other Copycat Birds

Like the brown thrasher, the starling, a small iridescently speckled black bird, mimics fellow birds’ songs, but it can also replicate other sounds. For example, if it lives on a farm, the starling can make a decent impersonation of sheep. If it lives in the city, it can make sounds that replicate a bus door swishing open or a police car’s siren. The mockingbird is the best copycat among bird singers, capable not only of precisely mimicking the songs of many birds, but also insect and frog sounds. The lyrebird of Australia is another marvelous mimicker, likely the most versatile worldwide; this bird can replicate a wide range of sounds from chain saws, car engines, and rifle shots to crying babies.

Birds Sing for Rights

Thrashers build nests close to the ground and compete for territory with their archrival, the catbird, which also mimics songs. The two birds can imitate each other’s voice, and when fooled by the other, they will fight to the death over nesting rights. Marking an area by song is a common characteristic among many songbirds. Certain rifts and types of song tell other birds that they are here, healthy enough to sing, and able to defend their space.

Most birds sing at dawn, in the morning hours, since their songs are their only property deeds and must be renewed daily. Dickcissels, sparrowlike birds, will spend nearly 70 percent of their day singing, as if the little birds need to keep speaking out to have their rightful claims heard. The tiny red-eyed vireo, weighing less than one-third of an ounce, will belt out as many as twenty thousand songs a day. Birds sing to warn other birds that they must be taken seriously. The skylark, for example, sings in flight, especially when eyed by a predator. Its song shows that it is exceptionally strong: not only is it able to fly and sing at the same time with such a vengeance, but it is also willing to give a fight of equal bravado.

How Birds Sing

Birds of the same species sing the same songs and seem to learn how to perfect variations from their fathers, since males frequently croon more than female birds. Some species are capable of learning melodies only during their first year and are called “close-ended learners,” while open-ended learners, such as thrashers, can pick up new musical numbers throughout their lives.

Some birds, like the Henslow’s sparrow, learn only one song, while the sedge warbler uses more than fifty distinct melodious harmonies that are long-winded and musically complex; this bird never repeats the same exact version more than twice. Songbirds have an organ called a “syrinx,” or voice box—two membranes at the bottom of their windpipe that vibrate when air passes through it. Birds with better muscle control around the syrinx can sing better songs. They also learn how to time and control their breaths. The canary, for example, takes as many as thirty short breaths a second, so as not to impede its musical number.

Birds Sing for Love

The most melodious bird songs are for love. A song’s complexity or sheer volume and persistence is meant to court and impress a potential mate with a display of virtuosity. Among songbirds, the males are usually most proficient, though the females are the judges and critics of their skill. Just as hip-hop songs might appeal to city dwellers, and a country song might seem just right while driving a lonely road bordered by cornfields, birds produce sounds to suit their surroundings. The “love songs” signal to a mate that they are well adapted to the ins and outs of their terrain.

What Makes a Hit?

Female birds are often attracted to complicated songs, and they might make the rounds checking out various males’ skills before making a decision. The nightingale, one of the few birds that sing at night, has over three hundred different love songs in its playlist. It shows the female that it is alert at all hours and a good potential father to protect the nest. The marsh warbler, a bird native to Europe, migrates in winter to Africa, though it mimics the songs of African birds when its looks for a mate back at home. Its song promises the female that it is an accomplished and experienced traveler, and likely to secure an exotic trip next winter. The brown thrasher male starts by blasting out his loudest song at the top of a tree. Once he has a female’s attention, he returns to the underbrush and sings softer melodies.

Life Cycle

Snakes, hawks, and owls look to thrashers as a meal. The catbird is an enemy to the thrasher’s eggs, breaching the nest and breaking them whenever it can. Nearly half of all thrashers, even when hatched, do not make it past the second year. But if a thrasher does learn the tricks of survival—and a few songs—it can live for about twelve years.

The sandpiper sings for five minutes straight while flying across what it claims as its territory, as if marking boundaries by song.

—

The female alpine accentor, a sparrowlike bird of Europe and Asia, is one of the few female birds that sing. She mates with several males and has a bunch of “fathers,” none of them certain of their paternity, helping her nurse and care for her eggs.

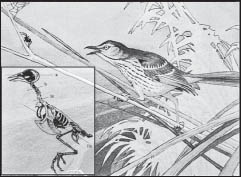

TIKBALANG

Filipino Horse-Human

The tikbalang is a legendary creature that lives in the forest and remote regions of the Philippines. It is a large beast standing over 6 feet tall that bears a head similar to a horse’s yet has a human body. It has long arms and human hands, though its legs are proportionate to a man’s and its feet are hoof shaped, giving it a stiff, upright posture. The tikbalang’s hair grows like a horse’s mane, in a Mohawk style, but it is made of bristles, similar to a porcupine’s quills.

Tikbalangs prefer to stay in heavily overgrown areas and congregate under bridges. It seems they eat bamboo, since most sightings have occurred in bamboo thickets. Besides traditional methods of camouflage, the tikbalangs avoid detection by blocking footpaths and roadways to confuse travelers, sending unwanted visitors in directions away from their hiding spots. When it rains while the sun is shining, many in the Philippines say a tikbalang is breeding somewhere. In some legends, the creature befriends individual humans and speaks to them. Historic records claim that some natives had captured tikablangs and domesticated them. If one is lassoed, a would-be tikbalang tamer has to ride on the creature’s backside as the beast dodges and leaps through the forest. If one manages to stay straddled, the tikablang will eventually concede defeat and let the person ride it whenever it wishes. In most accounts, a tikablang does not harm humans, and some of the younger ones occasionally break the species’ rules of strict secrecy to watch children at play. Sometimes the beast might briefly join in activities, such as fetching a foul ball, before vanishing into the forest.

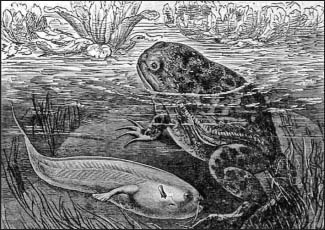

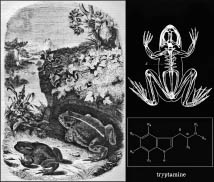

TOAD

Toxic Wart Wearer

The toad seems like a stoic little creature, sitting on a stone in the forest, patiently waiting for an insect or grub to pass within reach of its long, sticky tongue. It rarely appears nervous or fidgety, though it will make a concerted effort to hop away if prodded or provoked. There are more than 300 species of toads, classified as amphibians, found in all parts of the world, with the exception of polar regions.

One reason the soft-bodied toad has the luxury of appearing calm in a natural world filled with larger predators has to do with its internal chemistry. The wart-covered skin of the toad contains a milkylike alkaloid secretion called “tryptamine,” similar to toxins found in some poisonous mushrooms, which causes hallucinations in humans and death to animals that ingest it.

Catching Warts

For centuries, mothers have warned children that handling toads will cause warts to grow on their hands or faces. However, even though a toad is considered an unattractive creature and, when attacked or handled roughly, can produce a poison that might cause a person severe pain, seizures, and cardiac failure, it will not give that person warts.

Life Cycle

Old toads, both the European and American variety, have been known to live up to forty years, though on average most frogs and toads live anywhere from two to fifteen years, depending on the species. Frogs have far more natural enemies than toads, although many snakes and some birds seem to be unaffected by toad venom.

Hallucinogenic Venom

A North American toad, Bufo americanus, is famous from coast to coast, especially after its psychoactive venom was classified as an outlawed substance by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, which warned people that “toads may not be licked.”

Frog vs. Toad

Toads are actually land-loving frogs, and both are amphibians, meaning that the first parts of their lives are spent exclusively in water. Hatched from eggs, frogs and toads are tadpoles in their youth, resembling a fish with a bulbous body and long tail, and only grow arms and legs as they mature. How long frogs and toads stay as tadpoles depends on the pond or stream where they were born. Environmental factors and water temperatures, as well as differences among various species, dictate whether a tadpole will remain in its fishlike form for as little as a month to more than a year. Once adults, frogs stay close to the water of their birth, while toads will head to drier ground and prefer never to be fully submerged again.

TUBEWORM

Dwelling in Diabolical Depths

On the ocean floor, where tectonic plates shift, raging bursts of superheated water erupt at temperatures exceeding 500 degrees Fahrenheit. No living thing should reasonably be able to live at such extreme temperatures. These hydrothermal vents spurt forth hydrogen sulfide and a slew of toxic minerals. The water is cooled rapidly by the freezing currents that occupy ocean depths, but these regions can often remain a bubbling cauldron and killing zone for distances of 200 yards. Hydrothermal vents or underwater hotspots, similar to “Old Faithful,” the geyser in Yellowstone National Park, vary widely in volume and intensity. However, right at the cusp of many of these vents, where water is near the boiling point, colonies of giant tubeworms have claimed this inhospitable ocean real estate as their own.

Blind Chemists

Living without sunlight, giant tubeworms have harnessed a complex assembly of bacterium partners to help turn hydrogen sulfide, a chemical that would burn the skin off your arm, into usable oxygen and nutrients.

The worm lives inside a protective sleeve made of a substance that is hard like a lobster shell and is topped with a bright red flowerlike plume at top. The red of its “head” comes from oxygen-rich hemoglobin, or red-blood cells, which acts as its processing plant to exchange chemicals that feed the bacterium that lives inside of it. Without arms, eyes, a mouth, or even its own digestive system, the tubeworm has perfected a process called “chemosynthesis.” The bacteria that live inside its tubular frame do all the work, turning the toxic soup of chemicals into life-sustaining nutrients that not only ensure the tubeworm’s survival but also allow it thrive.

A giant tubeworm grows to lengths of more than 7 feet. Inhabiting an environment more akin to some alien planet, it has no predators and can live for more than 250 years.

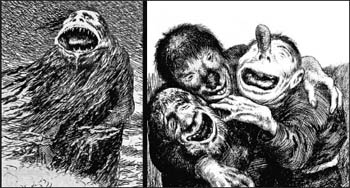

TROLLS

Nordic Neanderthals

A legendary race of primates known as trolls, called “jötunns,” or monsters, in Norse mythology, are described as heavyset beasts, about 7 feet tall (despite their reputation for being short) and covered with fur or long hair. According to Scandinavian folklore, they had humanlike faces and limbs, but with lobe-shaped noses, and larger, cuplike ears that were located higher up on the side of their heads than humans’ ears. Myths that they lived under bridges and collected toll for safe passage were later made popular in German folklore as stories of bridge-dwelling trolls featured a dwarfed version of the original oversized Scandinavian troll.

Trolls lived in isolated mountain ranges and inhabited caves. They were extremely powerful, with muscular forearms, and could toss heavy boulders for long distances. The early human inhabitants of the area passed on oral legends about the species, which were said to be carnivores and not afraid of hunting men or eating them. The origin of the creature was unclear, though various mythologies reasoned that trolls were born out of the armpits of a giant. It has been speculated that troll mythology grew from early human encounters with Neanderthals, which also once inhabited Northern Europe.

Encounters with Trolls

Our earliest relations broke from apes about fifteen million years ago. None of the earliest hominids closely resembled us physically, though they were bipedal beasts with problem-solving brains. It was not until about 500,000 years ago that Hominidae began to appear, which acted and appeared more like modern humans. The well-documented Homo erectus, a low-browed, brutish species seemed to vanish about 300,000 years ago, and by 195,000 years ago, creatures more like ourselves came on the scene, sharing the hominid stage for a time with Neanderthals.

What other small bands of hybrid, humanlike creatures flourished in isolated pockets throughout the world is unknowable. Yet it is possible that legends and mythologies grew from oral histories concerning our encounters with humanlike species during our long migratory history.

Fossil evidence clearly indicates that Homo sapiens sapiens, or modern man, encountered Neanderthals, a separate species from us that vanished only about thirty thousand years ago.

TULLY MONSTER

Pole-Eyed Beast

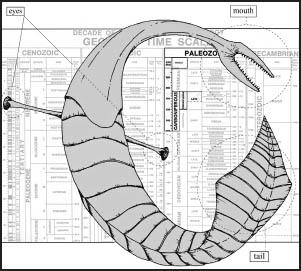

Tullimonstrum is an extinct mud-dwelling creature that existed about three hundred million years ago when North America was partially covered under a shallow sea. (Fossils of the “tully monster” were first found in Illinois.) In that era all the landmasses were so lopsidedly rearranged that nearly all the midwestern states were situated at the earth’s equator. Nevertheless, this creature had one of the most improbable body designs ever constructed, with a headless, sluglike body, two fins, and a long nose with a pincer on the end that contained eight tiny teeth. In addition, it had some form of rudimentary eyes located at the base of its polelike fins. As bizarre as it was—its design was never replicated—it seems reasonable, as biologists speculate, that this animal may have eventually developed into some variety of worms. As of now, the tully monster is classified as an animal, but thus far it belongs to its own phylum.

The Order of Life

In the mid-1700s, Swedish scientist Carl Linnaeus devised a system that classified all living organisms into categories and lists, a system that is still used in biological sciences today. He divided forms of life into a descending list in which they first belong to a kingdom, then a phylum, class, order, family, genus, and finally a species. Considered a genius and the Einstein of his time, Linnaeus grouped organisms by physical similarities. His list intrigued many and began the serious scientific inquiry into man’s origin, sparking a search to find where we fit into this all-inclusive directory of living things.

TURTLE

Armored Ancients

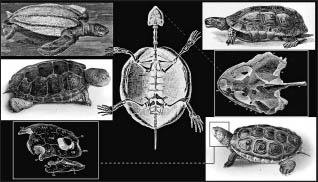

Turtles live both on land and at sea, but all are reptiles distinguished by their bony shells, extensions of their ribs that serve as shields for their backs. The bottom or belly of the turtle shell is called a “plastom” and is actually an elongated collarbone. The two halves of the turtle shell are connected by muscle hinges that allow it to close tighter. This adaptation helped make the turtle one of oldest types of reptiles, existing from 215 million years ago, well before lizards, crocodiles, or snakes appeared. They lived alongside dinosaurs and then outlived them all.

Today, there nearly 250 different species of turtles. The leatherback sea turtle ranks as the largest, with a 6-foot-wide shell and weighing 2,000 pounds. The smallest is the South African padloper tortoise, growing to only about 3 inches. The meanest of the bunch is the snapping turtle, of which there are 2 species, the common snapping turtle and the alligator snapping turtle. Both have sharp hawklike beaks and can bite off a human finger with one chomp. They are even more than bullies to their own kind and are cannibalistic. The snapping turtle will devour a smaller member of its species without a second thought.

Portable House

Tortoises—land-dwelling turtles—generally have larger spaces inside their shells than their aquatic relatives, allowing them to fully draw all their limbs and their heads inside. Tortoises have eyes facing downward, while those of aquatic turtles face upward.

A turtle’s beak is rigid, and the only part of its body that it can move fast is its head, a necessity for catching swift prey. Some turtles, like the Florida softshell turtle, are carnivores; many are omnivores; and some eat only plants. Aquatic turtles can hold their breath for as long as seven hours. Even turtles living in arid regions need access to freshwater, while marine turtles have adapted to drinking seawater by eliminating excess salt through their tear ducts. All turtles lay eggs, and even sea turtles must breach the protection of the ocean to deposit their eggs on the shoreline. Young turtles are orphaned from birth and have no parental care or guardianship. The turtle never sheds its shell, which remains its permanent abode, growing larger as it matures. Aquatic turtles have lightweight shells, while tortoises’ shells are usually thicker and heavier, but a lifesaving burden.

Life Cycle

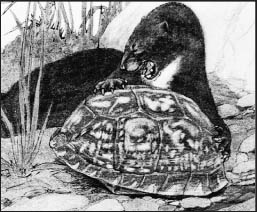

Marine turtles are sometimes preyed upon by sharks, though most have few other natural enemies once fully grown. At birth, turtles are at their most vulnerable, especially sea turtle hatchlings, which must make it to the shoreline from their beach mound nests. Seabirds and shorebirds pick off the hatchlings as easy late-night fare; so do fish and crabs. Tortoises are attacked by raccoons, snakes, coyotes, and birds of prey. Despite the significant mortality among the young of many turtle species, nature seemed to give the slow steady turtle the benefit of longevity. Averaged across all species, the turtle has a life span of about fifty years, but some have lived more than two hundred years.

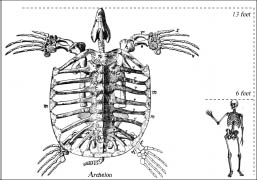

The largest known turtle of all time was the Archelon, which died out sixty-five million years ago and measured 13 feet long and 16 feet wide.

All turtles have tremendous night vision and see in more colors than humans.

—

English General Robert Clive had a massive pet tortoise, “Adwayita,” received as a gift while he was in India in the late 1700s. It was transported to a London Zoo in 1875. The tortoise died in 2006 of a cracked shell at 250 years old.

TYRANNOSAURUS REX

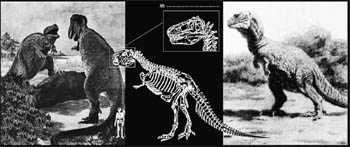

Largest-Ever Predator

The most well known of all dinosaurs, T. rex was the largest land carnivore that ever existed. Its Latin name means “King tyrant,” and it’s a highly appropriate one considering the dinosaur grew to over 40 feet long and weighed 7 tons. Its legs alone measured 13 feet to the hip, and it had a 5-foot skull with a mouthful of 12-inch teeth. There were at least 30 species of Tyrannosaurus, found in Europe and Asia, though the largest of its kind roamed the landscape of what is now western North America. As a species, the T. rex only had about a million-year reign. However, during its heyday, it was hard to outwit, since it had excellent vision and a keen sense of smell.

It did not walk upright all the time, with its head held up high, Godzilla style, as generally depicted, though it could stand up to fight and scan the horizon. Instead, it leaned forward as it ran with its heavy tail counterbalancing its massive skull. The tail pointed straight out and was perpendicular to its legs. It certainly was a meat eater, but it seems this hulking monster did not like to pick a fight as much as originally believed. Since its arms were small and awkward, it’s unlikely that hand-to-tooth combat was its favorite mode of attack. It could be compromised easily and killed from below by gut punctures made by smaller dinosaurs during battle. It probably preferred to sneak up on other grazing beasts and then pounce and kill with tremendous force. The infamous T. rex was just an overgrown scavenger, preferring to pick the remains of what other dinosaurs had killed.

Why They Died

Very few juvenile fossils of this species have been found, suggesting the T. rex was extremely protective of its young. Apparently it kept its brood under fierce guardianship for four or five years. The full-grown T. rex had an average life span of about thirty years. The species died out at around the time of the K-T event sixty-five and a half million years ago, but it was one of the last of the larger dinosaurs to disappear. As both a hunter and a scavenger, the T. rex survived slightly longer, but it was ultimately unable to avoid extinction. It is possible the T. rex was not able to digest bacteria-laced carrion, which was plentiful, and needed fresh meat, of which there was less and less available to meet its huge daily demand.

Although enormous, the T. rex’s bones were nimble, and its joints were fused in such a way as to give it the agility comparable to much smaller darting lizards.

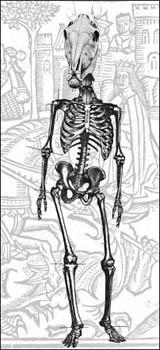

Jurassic Park

The novel and movie Jurassic Park about cloning dinosaurs from blood found in the bodies of insects is based on a factual premise. Dinosaur DNA still exists; many samples of prehistoric blood are preserved in the stomachs of mosquitoes that lived 140 million years ago, particularly specimens sealed in ancient amber or fossilized tree resin. Although no complete sequences of dinosaur DNA have been found, it is one day theoretically possible to have a T. rex or any number of dinosaurs reborn, or at least genetic versions duplicated.