CALADRIUS

Dr. Bird

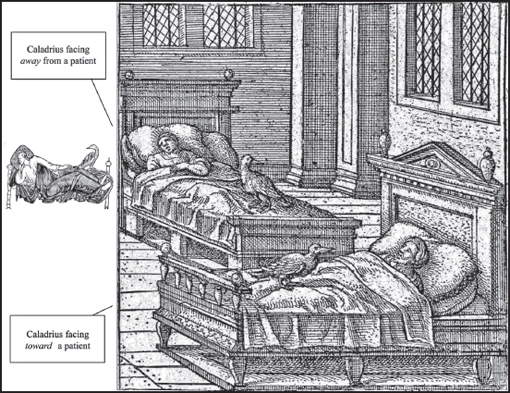

This all-white bird had remarkable powers to detect human sickness and death, according to Roman legend. Supposedly, caladrius were used by ancient Romans to determine the seriousness of illness. If the bird turned its back on someone sick, all further treatment would be halted, because the patient was destined to die. There apparently were cases when the caladrius hopped along the chest of the infirm until reaching the face. It then plucked a hair from the eyebrows or head, immediately took flight through an open window, and made a beeline straight up into the clouds. It was thought the caladrius took the sickness with it into the heavens and had it burned off by the sun. Caladrius, thus, were the last hope of the terminally ill.

No Free Checkups

Caladrius had special handlers, since it was a rare and an expensive fowl that only royalty could afford. Sellers of the birds kept them under a cloak, for many people came pretending to want to buy a bird but were actually only trying to get a free medical checkup by provoking the bird to look at them. Ancient medical books recommended caladrius droppings as a good salve for the eyes. Although the bird is presented in numerous antique royal coats of arms, and eyewitness accounts of its abilities are recorded, the species with these mortality-predicting properties, for reasons unknown, has not been seen for over three hundred years. Some have variously speculated that the caladrius was really a heron, an albino parrot, a type of dove, a seagull, a white wagtail, or perhaps an extinct species.

CAMEL

Masters of the Desert

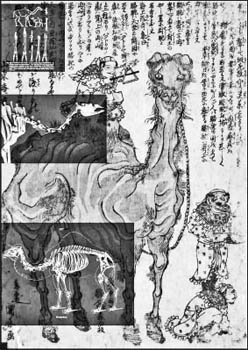

Camels come in only two models, the one-humped Arabian camel and the two-humped Bactrian camel. Related to llamas, alpacas, and the South American vicuñas, camels share a distant common ancestor that originated in the prehistoric savannahs of North America around ten million years ago. The first camels migrated to Asia when a land bridge connected continents. They congregated around the northern parts of Africa where they effectively adapted to surviving in harsh desert conditions. Ancient camels were immense and are estimated to have been twice as large as the modern versions. Records show that people of the Middle East and Red Sea regions first domesticated camels around 2,000 B.C. There are only about 1,000 wild camels left in the Gobi Desert, but as a species, there are more than 12 million domesticated.

Sandproof

Adult camels measure around 7 feet high at the hump. They have long legs that can land a kick in four directions. Their two-toed feet prevent them from sinking into sand. They can sprint to speeds of 40 miles per hour and maintain a steady gait of about 25 miles per hour for long distances. Camels have long eyelashes and ear hairs, in addition to sealable nostrils, which make them unperturbed by sandstorms.

Camels can draw foul-smelling liquid up from their stomachs and spout well-aimed streams of spit through their split lips when annoyed or as a means of defense. The insides of their mouths are so rough they can eat thorny bushes as sharp as coils of barbed wire without a hitch.

Walking Canteens

The hump, believed to be the secret to the camel’s unique ability to go without drinking water for long periods, was thought to be an actual reservoir, like a tank filled with sloshing water. It’s true that a camel can drink up to forty gallons of water at one time and not need another sip for weeks, but its hump is not hollow. Instead, it’s made of fatty tissue that serves as a energy source during long treks. However, the real trick to the camel’s ability to survive extreme conditions that would kill almost all other animals rests in its blood cells. Camels are the only mammals with oval-shaped red blood cells, which are also found in some birds, fish, and lizards. Unlike the circular cells we humans have, these cellular canteens can expand to let the camel consume excessive amounts of water at one time without bursting and they act as effective water regulators, distributing stored water-dense body fats as needed. A camel can live for around forty-five years.

A camel can withstand temperatures reaching 106 degrees Fahrenheit without breaking a sweat.

—

The name camel comes from an Arabic word meaning “beauty,” and although camels do not have the prettiest faces among animals, their comeliness lies in their unique adaptations.

CAPYBARA

World’s Largest Rodent

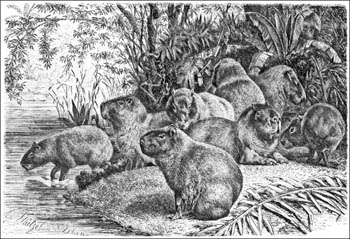

Among the 4,000 different kinds of mammals on the planet, nearly a quarter are classified as rodents. The South American capybara takes the title as largest in its class, growing to 4 feet and weighing about 150 pounds. It looks like a giant guinea pig, though with longer legs and webbed feet. Its hind legs are a bit taller, which makes its rump protrude higher than its head. Capybaras have brown fur and no tail and live in marshy areas or near rivers and lakes, grazing on grasses and aquatic plants. They usually stay in groups of ten or more and are playful with one another, rolling about in mud and communicating throughout the day in a call that sounds similar to a dog’s bark.

They also escape big cats and land predators by hiding underwater for long periods. They are much more agile underwater and often sleep there, floating with their noses sticking just above the surface and camouflaging themselves among the reeds and grasses. They mix up their feeding patterns and grazing times and seem to eat whenever they are hungry during both day and night. Anacondas, the massive South American snakes, are the capybaras’ greatest enemy. Capybaras live for about ten years.

Capybaras have a network of defenses that include sentries, who are young males assigned to keep watch for predators. They sound a warning alarm to the group when danger is near. They all start barking, which makes it seem as if a pack of hunting dogs has infiltrated the area.

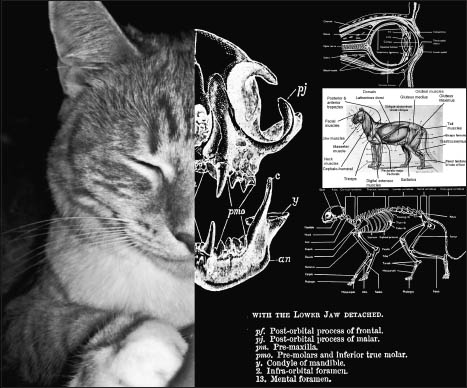

CAT

Favorite Feline

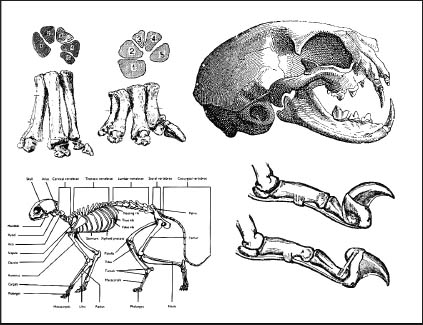

Aloof, primitive, and mysterious, the house cat is the most popular pet in the world. It was first domesticated from the African wildcat more than ten thousand years ago. Early agrarian civilizations of the Middle East, notably the Egyptians, encouraged wildcats to catch mice that plagued their grain stores by leaving treats, until a breed of the cat was tamed enough to live among humans. There are now nearly 80 breeds of domestic cats, and an unknown number of feral cat combinations. None, however, have entirely lost the wildcat instinct. Cats, all 500 million found everywhere in the world, are carnivorous. They are agile and swift, instinctively knowing how to stalk and pounce on a moving object as if it were prey.

Cats have slit-shaped vertical pupils that can expand to cover the whole eye, allowing them to see far better in darkness than humans. But their noses, which have ridges like fingerprints, are cats’ most important sensory organs. They have scent glands on their cheeks and back—which explains why they curl around your legs, marking territory—and are always sniffing out pheromones and food.

They lick themselves exceptionally clean after every meal, concerned more with odor removal than sanitation. Although instinctively solitary hunters, cats are social animals and express themselves by tail movements, body language, and by verbally using a variety of hisses, purrs, growls, and meowing. Most cats weigh about 8 to 10 pounds, but some breeds like the Ragdoll can reach 25 pounds, while the smaller Singapura cat can weigh as little as 4 pounds.

Why Cats Are Loved

Ailurophilia, the love of cats, was a tradition started by ancient Egyptians, who eventually elevated the cat to the status of a god. Egyptians shaved their eyebrows as a mark of grief when a pet cat died, and noteworthy cats were mummified. Many were entombed along with mice, so the cat would have a meal when it revived in the afterlife.

It is the combination of aloof primitiveness and warm empathetic properties the cat is said to possess that attracts cat lovers—not to mention their cuteness. Even so, domesticated cat popularity has ebbed and waned throughout history, never more so than during the Dark Ages. In the fifteenth century, Pope Innocent VIII declared that cat lovers were witches fit to be burned at the stake, and Europe purged its cat population, a trend that lasted until the eighteenth century.

Nine Lives

The saying “Curiosity killed the cat” is only partially true, even if a cat’s natural prowling instincts often leads it into precarious situations, such as climbing high into trees, traversing roof ledges, or exploring any nook or cranny in which it can fit. Cats have a supple spine and neck bones that enable them to land on their feet if they should fall doing one of their acrobatic stunts. Their ability to survive falls combined with their quick reflexes, which allow them to stay just ahead of danger, feed into the myth that cats have nine lives. Even though the phrase has come to describe a person who seems to narrowly avoid mishap time and again, the cat’s legendary “nine lives” myth likely stems from ancient Egypt, where both cats and the number nine were held to be sacred. In reality, the house cat has only one life, of course, but it lives on average from twelve to fourteen years.

Cats have retractable claws, sharp teeth, and exceptional hearing that can detect low-frequency sounds, just the kind made by rodents like mice.

—

The scent capabilities of house cats are more than twelve times as sensitive as ours.

America’s Top Ten Pets

1. Cats

2. Dogs (More households have dogs, but most cat owners have more than one cat.)

3. Fish

4. Hamsters

5. Mice

6. Guinea Pigs

7. Birds

8. Snakes

9. Iguanas

10. Ferrets

United Kingdom’s Top Ten Pets

1. Dogs

2. Cats

3. Rabbits

4. Birds

5. Hamsters

6. Horses

7. Snakes

8. Gerbils

9. Turtles

10. Rats

Ancient sailors relied on a cat’s instinct to sense approaching storms. Cats were welcomed aboard ships (their rodent-hunting skills were appreciated, too) and were subsequently transported around the world via trading routes.

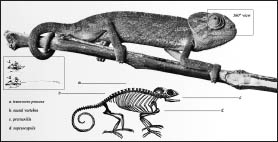

CHAMELEON

Master Mimic

There are more than 160 species of chameleons. Chameleons are most famous for their ability to change color and quickly blend into virtually any background. This gift has served them quite well, given that fossil evidence suggests the chameleon has been around for at least fifty million years. Some grow to only 1½ inches long, while others are bigger than 2 feet.

The chameleon has a series of specialized cells in its skin that contain color-modifying pigments, allowing it to simulate the color of its environment and conceal itself from predators or prey. Some change color to show mood, turning darker colors when angry or upset. Others modify color to attract mates, as they try to show off during this period, often displaying a rainbow of colors. The species of chameleons capable of changing colors seem to love to remain a vibrant green, or a simple understated brown, though they can be blue, red, pink, purple, orange, or yellow, and any partially striped and molted color in between.

Two Worlds in 3-D

Chameleons have two independent stereoscopic eyes, meaning that like us, they can perceive depth, distance, and perception. However, instead of processing this into one image the way we do, a chameleon sees two distinct 3-D views from each eye, giving it a strangely kaleidoscopic picture of reality. Each eye can rotate in different directions, and when the eyes overlap in range, a chameleon can see things in a 360-degree arc above, below, and all around its body.

Lightning Licker

Chameleons top the reptile charts for having one of the fastest tongues. Some chameleons have tongues that are twice as long as the length of their bodies and can snatch an insect faster than the human eye can see, or about thirty one-thousandths of a second.

Chameleons have no ears and are most likely deaf, living in a silent world, though they can sense vibrations through their feet.

Nervous Pets

Chameleons, by their nature, prefer to stay concealed, and would rather not be touched by humans. As pets, however, they usually live from two to three years, if well fed and left unmolested, but some have survived for ten years. In the wild, depending on the species, females usually live for eight years, while males live for only five.

Although philosopher John Locke said, “We are like chameleons, we take our hue and the color of our moral character, from those who are around us,” the chameleon reptile changes color for communication and camouflage.

—

A chameleon’s upper and lower eyelids are fused, leaving only a pinhole aperture, a feature that turns its eyes into binoculars that are capable of spotting an insect the size of a fly from 30 feet away.

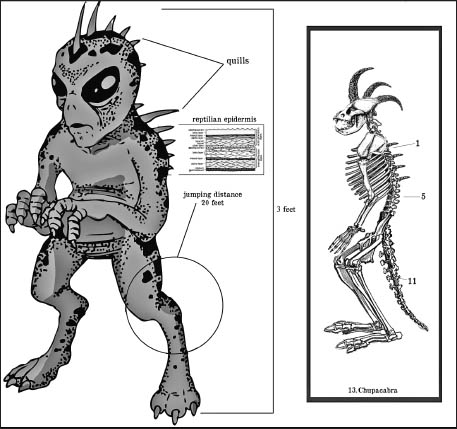

CHUPACABRA

Vampiric “Goat Sucker”

Beginning in the 1950s, reports began to emerge from Puerto Rico of a creature that was attacking livestock in a bizarre manner. Whatever it was, this predator didn’t kill its prey for meat but instead left carcasses totally drained of blood. In the mid-1990s, when hundreds of animals were found dead from having their blood drained, the new beast was dubbed chupacabra, a Spanish term for “goat sucker.” In 1992, the Puerto Rican newspaper El Nuevo Dia described the chupacabra as “a raging beast, thirsty for blood, and a servant of the devil.”

What It Looks Like

Chupacabras allegedly have been sighted on many Caribbean islands, in Central America, as far north as Maine in the United States, and most recently in Russia. Puerto Rico, however, still has the greatest reports of chupacabra activity, with more than two thousand attacks on the island’s livestock.

It supposedly moves in a hopping manner similar to a kangaroo, though at a much faster gait, and can bound 20 feet horizontally. It is about 3 to 4 feet tall, thick bodied like a bear, and appears greenish, or black gray, in color. It has hornlike protrusions (or spiky quills) on its head that run down its spine to the base of its tail. A chupacabra has a hyena-shaped head and canine snout with sharp incisors, though it screeches and hisses rather than growls. Those who have gotten close enough claim chubacabras have red eyes, though probably from the glare of flashlights, the same way a dog’s eyes appear frequently in photos. Chupacabras leave an unpleasant sulfuric, rotten-egg smell that lingers for some time.

Methods of Attack

It kills its prey by making three triangularly placed puncture wounds, usually on an animal’s chest. The chupacabra is apparently strong enough to overwhelm its quarry by flipping it on its back. It then uses its weight to restrain its catch while draining the animal’s blood. Although goat blood is said to be its favorite food, other livestock has been discovered bled dry and with internal organs removed.

Is It Real?

Scientists have attributed chupacabra sightings to stealthy panthers that were introduced illegally into Puerto Rico or to coyotes with parasites and mangy skin that make them look monstrously ugly. One of these predators may bring down a goat, but then abandon the carcass, for some unknown reason, leaving it to bleed to death—and hence creating the appearance that its blood was sucked. Others allege experiments in genetic mutations or cite radioactive fallout or some environmental chemical deviation as the cause for the emergence of this biological abnormality. It is true that Vieques, an island located 8 miles east of Puerto Rico, had been used for numerous military war games for many decades by the U.S. military. The island and surrounding vicinity were used as Cold War bombing ranges and testing grounds, with suspicions that atomic and even nuclear weapons had been discharged there. According to this theory, the chupacabra could be a Caribbean Godzilla, a beast mutated into existence by the atomic age. Still, it remains a mystery exactly why sightings of this new vampirelike beast continue.

Eyewitnesses describe a creature that appears half reptilian and half canine.

Genetic Drifting Goat Sucker

Inherited traits found in a group of organisms often change over time in order to give it a better chance of surviving in an altered environment. Sometimes a mutation produces an organism that is suddenly more suited to rapidly changing conditions. In animals, as evidenced by fossil records, major modifications within a species by and large require eons to take hold, but every so often survival depended on speedy adaptations. In the microscopic world, certain viruses can alter within days. Entire populations, for example, as observed with various strains of staph viruses, can mutate so rapidly they often become resistant, seemingly overnight, to antibiotics that had once killed them easily. Some theorists claimed the chupacabra was a result of secret genetic mutation experiments.

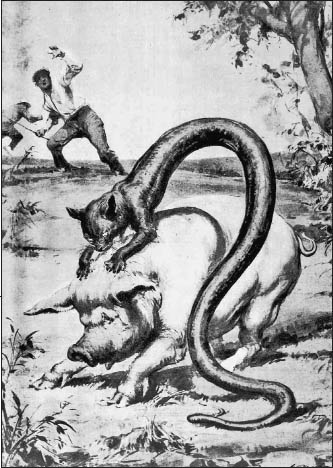

The Beast of Bladenboro

In 1954, the small North Carolina town of Bladenboro made national news. Dogs, goats, and small livestock were found dead, completely drained of blood. The carcasses remained uneaten, though many had their jaws broken or their skulls crushed. Eyewitnesses said the creature responsible was at least 150 pounds and dark colored, though it made an eerie sound like a baby wailing, or to some it sounded like a woman crying hysterically. Its echo carried far through the mountains. These savage killings terrified the community and none dared walk alone without a firearm. Some thought it was a human transformed into a vampire, but further sightings and investigation by trackers indicated it was some type of mysterious large-pawed, catlike beast that had a serpentine tail. Professional big game hunters and sniffing dogs flocked to the area, though bloodhounds curiously refused to follow the scented trail. Nobody could catch the beast. Once the small town became overrun with hunters, the killings stopped. What the beast was—whether a chupacabra, an alien big cat, or another creature—remains a mystery.

COBRA

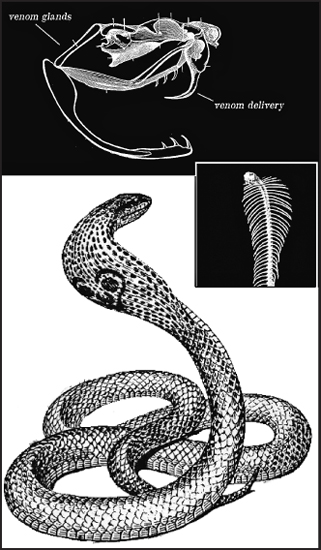

Nature’s Deadliest Fangs

To be a snake, a creature having only a body without limbs and a mouth to eat with, would seem to be a great disadvantage. While the trend among almost all creatures was toward the development of limbs, the snake’s limbless form passed through the maelstroms of environmental change, surviving by seeking rapid shelter underground, where it could hide in the narrowest apertures. As the dinosaurs died off and the age of mammals arose, with rodents abounding, the snake was ready to take advantage of this food source and perfected ways to capture prey and defend itself from predators. The first venomous snakes appeared during the waning years of the dinosaur era. This adaptation gave venomous snakes an even more potent edge that made them serious competitors in the ecosystem. Poisonous snakes were a significant cause of death among primates and early humans. For this reason, many say the fear of snakes, called “ophidiophobia,” is embedded in our collective unconsciousness. There are 2,000 species of snakes, with about 400 producing venom dangerous to humans.

How to Slither

The snake’s movement appears seamless. It has perfected gliding through all sorts of terrains, swimming proficiently and climbing trees without a finger or a foot. It uses its head, belly, and the friction caused by its scales to gain traction. In essence, a snake pushes its body sideways, following the direction of the head, by constricting a series of muscles, a segment at a time, to go forward, thus using this back and forth rippling to achieve thrust. If a snake is on an unstable surface like sand, it must shift its entire body sideways, called “side-winding,” since the surface underneath dictates exactly how a snake must ripple or curl its body to achieve locomotion.

In the Hood

There are over 250 types of cobras, classified as Elapidae snakes, which include poisonous coral snakes, mambas, and true sea snakes. They are found in the hotter parts of Africa, Asia, and Australia. Cobras arguably are the most iconic snakes, noted for their threatening posture of raising their hooded heads when angry or disturbed. The hood is actually an extension of the snake’s ribs and is an evolutionary feature that makes it appear larger and more foreboding. It has two front, elongated fangs, with tubes connected to venom sacs, which are modified saliva glands located behind its eyes. Cobras strike at lightning speed, clocked at 150 milliseconds, which is half the time it takes to blink your eye. The snake then clamps down until the sharpened fang tips inject all the venom with the efficiency of a syringe. Cobras move by wiggling or lateral undulation, as all snakes do, but some cobras can race across the ground as fast as 40 miles per hour.

The cobra’s hood—just like the bright color of a coral snake or the rattling tail of rattlesnakes—is an adaptation designed to warn predators of the cobra’s potential poison. It’s an advertisement that reads, “Don’t mess with me.” Some animals, notably mongooses and certain birds, have built up an immunity to snake venom, though few living things can survive the bite of a cobra, especially the Egyptian cobra. This cobra can grow to nearly 10 feet and injects a nerve-paralysis toxin, which rapidly impairs breathing and swallowing, leading to suffocation.

The king cobra is the largest venomous snake in the world, growing to 25 feet in length. Despite its girth, it is excellent at climbing trees, swims rapidly, and delivers a bite that kills a person in fifteen minutes. The spitting cobra does not even need to get close to strike and can squirt its venom perpendicularly, with bull’s-eye accuracy, from 6 feet away. Being hit in the eye with the spitting cobra’s venom will cause blindness.

Life Cycle

The king cobra, unlike other cobras, builds a nest and lays its eggs there. However, the mother abandons it shortly before the eggs are ready to hatch. Were the mother to be present when its eggs hatched, she would eat them. If they survive their mom, young kings, like most cobras, can live for about twenty years.

Cobras eat other snakes, in addition to mammals, birds, and reptiles, and they sometimes sustain injuries during fights that eventually kill them. Some cobras seem capable of digesting snake venom, if they eat a rival poisonous species or consume an animal that they just poisoned with their own venom. But they can die if another venomous snake bites them and injects its poison directly into their bloodstream.

The second-deadliest venomous snake in the world, the black mamba, is also the fastest, so adept at slithering it can travel 15 feet per second.

—

A cobra dispenses as much as two hundred milligrams (roughly two teaspoons) of venom in a single bite, an amount potent enough to kill a full-grown elephant within a few hours. A person or an animal bitten by a cobra usually has less than a 25 percent chance of survival.

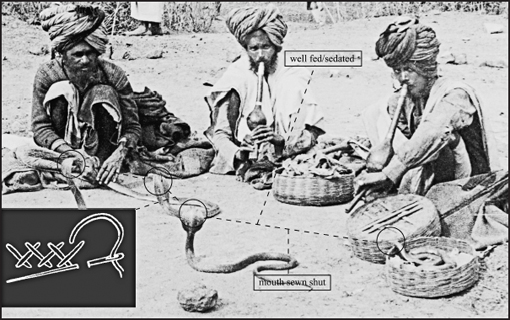

Snake Charmers

Cobras cannot hear the music played by snake charmers in India since snakes are essentially deaf. What captures the Indian cobra’s attention is the sway of the flute. It moves its head to keep the flute hypnotically in its vision. Snake charming was a dangerous profession, and during ancient times, it was an art that was passed down from father to son. Since many snakes do not need to eat more than once a week, the snakes used in charming were well fed and sluggish; sometimes the snakes’ venom glands were removed or their mouths were sewn closed. Nowadays, Indian snake charmers are like wandering street performers, working for handouts. Some charmers have diversified; for a fee, they perform magic spells and induce healing by using the snake in ritual practices. Others charge for pest control services to rid a house infested with snakes and do so by attempting to lure the invaders out with their flutes.

Young cobras are ready to defend themselves within three hours after hatching and are born with venom as potent as the adults’.

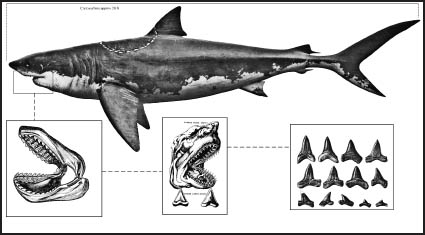

CRETO SHARK

Mega “Jaws”

Prowling the world’s oceans ninety million years ago, this granddaddy of the great white shark, Cretoxyrhina, was a 20-foot marine beast that had as many as 450 teeth in its deadly jaws. Its mouth was like a cutlery store: each of its teeth was 3 inches long and as sharp and strong as the best paring knives. For this reason, this extinct creature has been nicknamed “The Ginsu shark,” after a brand of supersharp knives made famous through TV infomercials.

Creto/Ginsu constantly opened and closed its mouth, chopping up anything and everything in its path. It liked to dice prey into pieces before eating, but if something was initially indigestible, Creto would throw up the bad food and try to eat it again. It was menacing to anything that happened in its path as it cut a wide swath of prehistoric oceans.

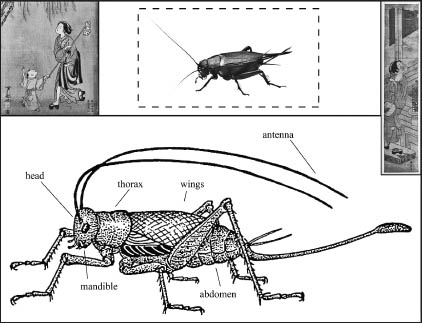

CRICKETS

Fiddlers of the Fields

Crickets are famous for their distinct musical chirping. Considered one of the best songsters among insects, crickets actually have a repertoire of four distinct tonal rhythms that all males, at least, seem to know how to play from birth. Females are usually silent in the cricket world, while males of the species sing or chirp from dawn to dusk, in a sort of obsessive-compulsive manner, playing the same song as many as eighty times each minute.

Why Do Crickets Sing?

The most familiar and loudest cricket songs are meant to attract females, while others are played to warn fellow males of their territorial rights. Once a female is in sight, a male cricket subdues his tone and plays a more mellow song, and after successfully courting, he strums out a short victory tune.

The flightless wings have protruding veins containing as many as 250 tiny teeth. The cricket lifts up and rubs one toothed wing against the other, similar to the way melodies are performed by running a comb along a corrugated washboard. Both male and female crickets can detect the slightest variations of pulse and beat, equipped as they are with an array of sound receptors, or ear holes, located on their front legs, just below the knees. By shifting a leg, they know the direction of sound and can calculate the varying distances to where other crickets are located.

A Life of Song

Many fables, songs, and poetry characterized crickets as squanderers of their short life, or as hopeless romantics, dedicating their entire existence to the pursuit of song and love. Ancient peasants thought the crickets’ songs were messages at the onset of spring, telling the farmers when to plant new crops. Others observed how crickets came into their homes and hid under beds days before the first autumn cold hit; some folktales portrayed them as wise and intelligent creatures. The talking cricket in Carlo Collodi’s novel The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883) was prudent and had lived in the toymaker Gepetto’s house for one hundred years. In Disney’s animated version of Collodi’s tale, Jiminy Cricket dispensed advice and good judgment as well.

Life Cycle

In the field, most crickets have a short life span of only eight weeks, which might explain why they seem to play a lifetime’s worth of songs repeatedly from spring through summer. As winter approaches, crickets try to find their way into houses or burrows and may live longer if kept warm. Many believe that a house cricket will bring good fortune and money, while others call an exterminator.

The cricket uses its wings to make sounds, not by rubbing its hind legs together as many believe.

Music Lessons

Chinese culture has long held a special place for crickets. The Qing dynasty court in the 1600s employed caretakers and music teachers to look after the little singers. An “orchestra” of crickets, kept in golden ornate cages, performed for the emperor and to the delight of visitors on festive occasions. Today, from May to July, Chinese markets still have vendors selling singing crickets, shouting “Jiao Ge-Ge” or “singing brothers.” Crickets are sold woven into small bamboo cages, which also serve as their food sources while singing in the buyers’ houses.

Cannibal Crickets

Generally, crickets are vegetarians, consuming all types of plants and organic materials. However, they seem to have a darker side, and when food is scarce, they frequently eat their dead. In addition, crickets are fierce fighters. Since the ninth century crickets were bred and trained like prizefighters. Today, the Association for Cricket Fighting in Beijing, China, keeps cricket winning records and sets rules for events. When a champion cricket dies, ceremonies are held, and some famous insects have been buried in their own gilded, miniature cricket coffins.

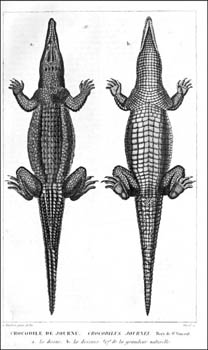

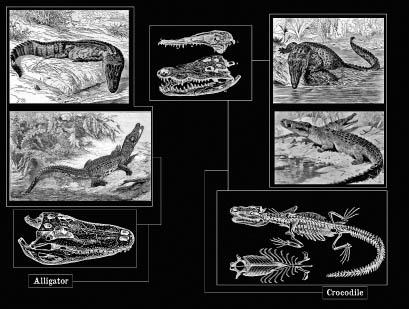

CROCODILE

Terminator Reptile

A cold-blooded crocodile is consistent in its approach to obtaining food, following the principles of survival long established in its prehistoric mind. It perpetually prowls or lies in wait until it finds something edible, and then it launches a ferocious ambush: be it fish, turtle, antelope, water buffalo, or an unfortunate human, a crocodile sees no difference. Crocs have even been known to attack and kill sharks.

When the Crocodilia species emerged over eighty-five million years ago, the earth was warmer than it is now. There were steamy lagoons and shallow seas, and volcanoes erupted everywhere, emitting bursts of deadly gases that choked the atmosphere. The crocodile was a contemporary of dinosaurs, and it is a “living fossil” by many standards, though it was more complex and adaptive than the countless extinct species with which it once competed. A gargantuan crocodile from the dinosaur era called “Super-Croc” grew 40 feet long and weighed 10 tons, as much as a city bus. Among larger primeval creatures, crocodiles were even then dominant in the food chain. The crocodile is encased in a hard, leathery armor, which ancient bestiary books claimed a lance could not penetrate.

Tricks of Its Trade

Crocodiles are rarely fooled twice by the same trick. They also have the patience of a stone and can remain in the same unflinching position, floating with only their nostrils and eyes above the waterline for more than a day at a time. They even have third eyelids, which are transparent and allow them to blink without giving away their location and swim underwater with their eyes open.

Despite being the croc’s legendarily powerful chomping force, its jaws have weak muscles for opening up its mouth, which can be held shut with one wrap of duct tape or by a clenched human grip. Crocodiles have small raised bumps on their jaws that resemble the stubble of a beard but are actually sensors. These detect when water pressure has changed, for example, caused by a potential food source entering a crocodile’s lair. These sensors signal when to get in motion and trigger the activation of its deadly force. In addition, a crocodile’s eyes are situated to give separate side views or produce binocularlike focus toward objects ahead.

Crocodiles have such powerful immune systems that sickness hardly infects them, and they survive even with severed limbs. They swallow rocks and pebbles to help their acidic stomachs grind and digest fur, shells, bones, and hooves. If no food is available, the beast can persist for up to a year without eating and yet remain alive and fearsome.

The Crocodile Speaks

Alligators and crocodiles are among the most vocal reptiles and can bark, grunt, hiss, bellow, and growl. From birth, soon after emerging from eggs deposited on shore in mounds of decaying vegetation, hatchlings squeal for their mother. Adults use different calls for hunting, or when feeling annoyed, threatened, or distressed. Adult males can also emit low-frequency sounds that ripple the surface of the water. They do this to scare up turtles or fish—and to attract females.

Life Cycle

In the wild, fully grown crocodiles have no natural enemies and are resistant to most diseases. Since they continue to grow throughout their lives, the length and width of the beasts are the best estimates of how old they are. You also can often tell the age of a wild crocodile by the number of stones and rocks found in its stomach. If not killed for their prized skins, crocodiles live to around seventy years, though some exceed one hundred. One in an Australian zoo was thought to be more than 130 years old.

Most Man-Eating

The Nile crocodile historically holds the record as the most man-eating reptile on the planet. One notorious crocodile, nicknamed Osama, ruled a portion of Lake Victoria near the village of Luganga for more than a decade. The croc ate a total of eighty-three villagers before it was finally captured. It took fifty men with ropes to wrangle the 20-foot-long beast from the water. Osama was not put down, but, instead, installed as the main attraction of a Uganda wildlife preserve and petting zoo in 2005.

Jaw Power

The devastating strength of a crocodile’s snapping jaws is infamous. Its mouth can clamp shut with over 2,000 pounds of force, the same as a car smashing into a brick wall at 60 miles per hour.

Alligator vs. Crocodile

There are 23 different types of modern crocodiles; some strains such as the dwarf crocodile grow to only 3 feet, while saltwater species have reportedly reached more than 20 feet in length. Crocodiles (their name comes from a Greek word meaning “lizard of the Nile”) live in estuaries, where saltwater and freshwater mingle, or in brackish saltwater, found in Florida and the Caribbean, South America, Africa, India, and parts of Asia.

Alligators have blunt snouts, better for pulverizing turtle shells, while the narrower-snout crocodile is more suited to catching fish and tearing into animals. Alligators grow to nearly 15 feet and tolerate only freshwater.

If an alligator and a crocodile squared off in battle, the larger and quicker saltwater croc would have to be the odds-on favorite. First each creature would try to intimidate its opponent by posturing to show its size and ferocity, since it knows that once locked jaw to jaw, neither would show mercy until absolute defeat of its opponent. If both were of equal size, however, the comparably stronger tail of the alligator could deflect the croc’s bite. In this scenario, the alligator, with its wider jaw, would likely prove victorious if it was able to inflict the first lockdown grip with its teeth.

Crocodile Tears

Legend has it that a crocodile would lure prey by pretending to weep and would eat anyone who came to offer it comfort. Crocodiles do cry, in a way, or are at least capable of producing tears, since they possess what are called “lacrimal glands” in their eyes. Their eyes will moisten involuntarily, especially if they have been on land for some time, in order to keep their eyes alert for the next meal.