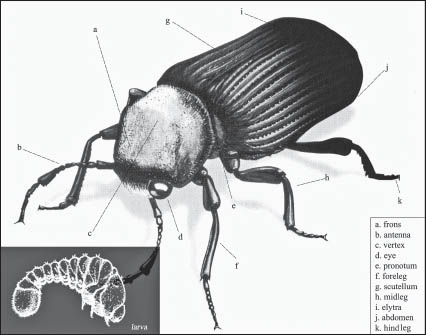

DEATHWATCH BEETLE

The Grim Reaper’s Tiny Messenger

Haunted houses make sounds, such as ticking noises behind walls, squeaky floorboards, and slamming doors. One insect to blame for some of the spookiness in old houses is the ominously named “deathwatch” beetle. This black, ½-inch, bullet-shaped insect eats natural sugars and cellulose found in wood. It doesn’t care if it gets its nourishment from a tree in the forest or from beams, rafters, or wall studs in a house.

During summer breeding season, the beetle bangs its head and raps its jaw against wood to locate a mate. It does this head banging in a relentless rhythm, lasting for hours. In medieval times, those keeping vigil with the sick were fearful of the sound, which echoed eerily in the quiet of the night. The tapping sounded like the staff of the Grim Reaper and superstitions arose that this abnormally persistent rapping was an omen and harbinger of death: the beetle was ticking off the minutes left on the death clock, or deathwatch, and was able to measure the time left before a life would end. As for the beetle, it usually only has a two-year life span before it meets its Reaper.

The deathwatch beetle originated in Europe and northern Asia but was transported worldwide during the era of shipping when goods were packed in wooden crates. It is closely related to two other beetles that are also associated with things that can shorten life span, namely the cigarette beetle and the drugstore beetle. However, the cigarette beetle does not smoke; rather, it eats dried tobacco. And the drugstore beetle doesn’t search out pharmaceuticals but instead infests dried, stored goods.

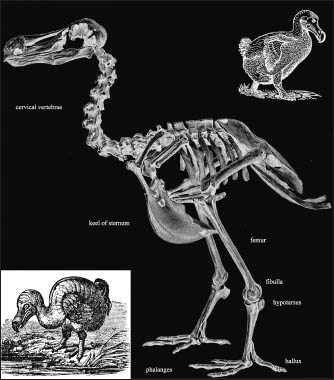

DODO

Too Nice for Its Own Good

A pigeonlike bird once flew from India and came to rest on the remote volcanic island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, 700 miles from the southeastern coast of Africa. It stayed there, and over many millennia in this isolation, it developed into a large, flightless species of bird that came to be known as the dodo. This stocky bird, similar in body shape to a pelican, with a blunt, hooked beak, stood about 3 feet tall and was as plump as a turkey at 45 pounds. It was brownish gray with short wings, tufted with yellow feathers; it appeared to have a fleshy, featherless head, though not altogether as bald as vultures. It also had a few long feathers sticking out at odd angles from its rear. Dodos dwelled in rugged, mountainous terrains, made ground nests, ate fruits and seeds, and usually preferred to live in solitude rather than in flocks.

Dead as a Dodo

When Western explorers reached the island in 1581, the birds were seemingly unafraid of their new visitors and did not attempt to seek cover or hide. On Mauritius, the dodo had no natural predators, such that over time, even the need to fly became obsolete. Unfamiliar with the need to worry about predation, they lacked the instinct to fear other creatures. This would prove to be their undoing. The dodo made for an easy catch for hungry settlers and their dogs. As far as wild animals go, the naive dodo seemed to the Portuguese a doido, meaning “crazy fool.” Within a century after its discovery, the dodo became extinct—and has since become the poster child for humans’ regrettably negative impact on wild places and species.

Some paintings and sketches were made of the dodo while it was alive, but exactly how it looked or behaved remained a mystery for some time. For many years, in fact, since no fossils of the dodo were found in Mauritius’s volcanic landscape (not a good sediment for fossil preservation), most assigned this so-called dodo bird to the “legendary” category, alongside unicorns. Even natives, when quizzed, said no one had ever known of or remembered seeing such a bird. In 1863, an English schoolteacher living on the island, George Clark, set out to prove that such a rare bird had, in fact, existed. Knowing the island’s terrain, he guessed correctly that animal bones never had time to settle and were probably washed off before fossilizing. He searched mud near river deltas and soon found a mother lode of dodo bones. Clark’s bones confirmed the dodo was real, and most museums to this day have specimens of the bird assembled from Clark’s finds.

Statistically, birds have the poorest chances of species survival. Out of the depressingly long list of extinct animals, nearly eight out of ten are birds.

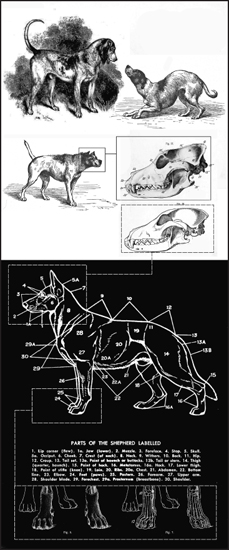

DOG

Most Faithful Friend

Dogs were our first alarm system. When originally tamed from a species of wolves, most likely the smaller East Asian wolf about ten thousand years ago, dogs served as a reliable security system for the caves and camps of our nomadic ancestors. Territorial and loyally devoted to the pack, be it led by dominant wolf or human, certain dog instincts have not changed. They still mark territory with scents, bare their teeth, growl, and bark at intruders or any perceived breach of their space. Some still bury a bone in the dirt from an instinct to preserve food for later, as if paying homage to their past, just as wolves, foxes, and jackals still do. However, most domesticated dogs could no longer survive in the wild.

Instead, many have become (or have been bred to be) specialists, from herding sheep, pulling sleds, sniffing out bombs, guiding people with handicaps, or expertly catching a Frisbee. An ancestral East Asian wolf is about 30 inches at the shoulder and weighs 60 pounds, while dogs now range in size from remarkably small breeds like the 6-pound, 9-inch Chihuahua to oversize breeds like the mastiff, which can weigh 300 pounds and, when standing on its hind feet, is over 6 feet tall.

How Dogs See the World

It was long believed that dogs are color-blind, seeing the world as images similar to old black-and-white movies on TV. However, even if they do not see in the range of colors that we do, their world is not colorless. Their eyes can register yellows and blues, with all the gray and brown shades in between. In low light, dog eyes work best, another remnant of their predatory past. In the dark, they see four times better than we do. They can recognize detailed features of your face within 20 feet. Beyond that distance, things get fuzzy for dogs, though they can detect the presence of something that’s moving or running nearly half a mile away. Another feature a modern dog still possesses from its wild ancestors is its third eyelid, which involuntarily moves up and down over a dog’s eyes like windshield wipers, removing dust and keeping its eyes moist. The dog really “sees” or interprets its world with its nose, and it combines these scent signals with visual images to produce a picture of things that would be hard for us to conceive. A dog’s olfactory capabilities are legendary, and we all know a dog would rather size up a person and gain information by first sniffing rather than looking at a face. Some breeds, such as the tracking bloodhound, have noses with 300 million scent receptors, while the average person has a mere 5 million.

The Dog’s Loyalty

Even in the first medieval texts about dog behavior, many incidents were recorded that described a dog’s unmatched loyalty. One such story explained that when one particular knight was held captive, all two hundred of his hounds went out on their own, formed a battle line, and freed their master. Another tells of the time when the Persian king Lisimachus died, and his faithful hound threw itself into the funeral pyre.

Drawing from more recent lore, newspapers covered the story about Rudolph Valentino’s dog, Kahar. When Hollywood’s first matinee idol died in 1926, Kahar waited by the door for two weeks for his master to return, refusing to eat until he too died. Dogs have been known to travel substantial distances to reunite with their lost families. One incident documented how a collie was lost when its human family was on vacation in Indiana in 1923. The family went home by car, but the dog traveled alone on foot, traveling 2,000 miles back to the farm where it was born in Oregon.

Dog Habits

Dogs are omnivores. They prefer meat, but they do eat plants, such as fallen fruit (consumed when they sense a nutrient deficiency or as a cure for an upset stomach). They also have no qualms about eating their own vomit. Dogs also lick themselves and nearly anything else, always willing to give something a sample taste. It was thought that if a dog licked a person’s wound it was as good as an antiseptic, but now we know this will only add more bacteria to the cut. Dogs contract all sorts of diseases, from worm infestations to blood diseases to cancer. The average dog lives about twelve to fifteen years. The oldest dog—one tough Australian cattle dog that died in 1939—lived for twenty-nine years.

There are more than 150 recognized dog breeds and countless mixed breeds. The total worldwide dog population is an estimated 400 million.

—

The dog’s ridged, rippled, and moist nose is as individual as a person’s fingerprints and interprets smells about ten thousand times better than we do.

—

In Roman times, the dog of a condemned man waited faithfully for a year outside the prison and howled uncontrollably when his master was finally executed. When the body was thrown in the river, the dog swam against the current to try to lift his lifeless master’s head.

Famous Dogs

“Lassie” was a male collie named Pal that became a star in the 1943 movie Lassie Come Home and was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. In 1959 he died of old age at age nineteen. Belka was a Russian dog and one of the first earth-born creatures to fly in a rocket ship into space and return alive. (He actually shared the cabin with a rabbit, forty-two mice, two rats, and a fly.) Of the forty-three U.S. presidents, twenty-five had pet dogs with them in the White House. One of the most famous was FDR’s Scottish terrier, Fala, which followed the president everywhere. Fala is even cast in bronze, sitting next to the executive chief at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, D.C.

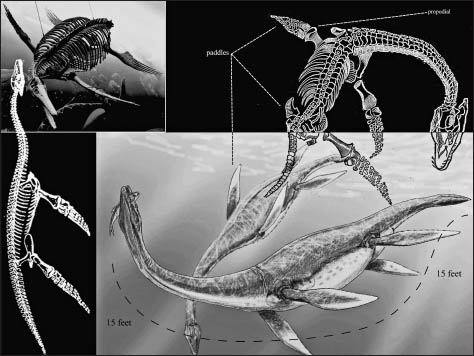

DOLLY (AKA DOLICHORHYNCHOPS)

Prehistoric “Sea Wolf”

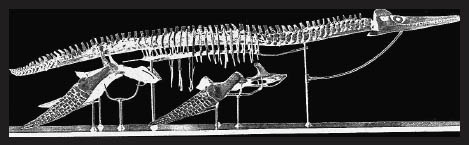

There were great schools of sea creatures known as Dolichorhynchops, or dollies, living in North America when much of it was covered under a shallow ocean eighty-five million years ago. These air-breathing reptiles looked like a cross between a penguin and a bottlenose dolphin, growing to 15 feet long. Dollies had long, stiff paddlelike front legs that served as fins, and snouts like a dolphins but with sharper teeth. Their rotor-blade-style rear fins revved these creatures up and made them fly through the water. Scientists believe they could shoot down to the ocean bottom like a torpedo and speed back up to the top, breaching the surface and becoming temporarily airborne. Dollies, as seals do now, may have leaped onto rocky outcroppings to sun themselves or hid in shallow inlets, especially when breeding. The first fossil of a full-grown dolly was discovered in the Kansas hill country in 1900.

Top Ten Biggest Dinosaurs

1. Argentinosaurus: Named after a fossil found in Argentina, this massive vegetarian was 130 feet long and weighed 110 tons. It had a long tail and an equally long neck. Its head was relatively tiny for all its massiveness, even if each of its vertebrae measured 4 feet in length. It lived about 90 million years ago.

2. Sauroposeidon: This 100-foot-long, 60-ton beast roamed the woodlands of North America 110 million years ago. Also a plant eater, this dinosaur had a disproportionately bulky body that supported a 60-foot neck. It’s speculated that it rarely held its head aloft since doing so would have made it difficult for its heart to pump blood to its brain. Instead, it likely ate low-lying plants and swung its head to and fro to gobble up foliage.

3. Spinosaurus: This 7-ton, 50-foot-long brute was the biggest meat-eating creature ever—even larger than the T. rex. It had long legs and small front paws, and a huge flap of skin on its spine that was as big as a ship’s sail. It terrorized the African continent until about 90 million years ago.

4. Quetzalcoatlus: This dinosaur was the largest creature on earth ever to take to the air. It had a 30-foot wingspan and weighed 200 pounds. It ate fish and meat and lived until 65 million years ago.

5. Dolly or Liopleurodon: This species of aquatic monsters weighed in at 30 tons and dominated the ocean from 165 to 150 million years ago.

6. Shantungosaurus: This 50-foot-long, 15-ton herbivore had a duck-billed mouth that housed thousands of teeth. It ground up its food supply of plants better than any modern-day juicer machine. It faded away 65 million years ago.

7. Utahraptor: This beast looked sort of like a giant chicken, though with massive killing claws on its feet. It was about 23 feet long and weighed about ½ ton.

8. Moschops: These fellows lived before that age of true dinosaurs, about 225 million years ago. They looked like a cross between a cow and a toad and weighed 1 ton and were 16 feet long.

9. Sarcosuchus: Called a “supercroc,” this 40-foot-long, 15-ton terror acted similarly to the modern crocodile, and dominated the world’s estuaries and rivers 110 million years ago.

10. Shonisaurus: This aquatic beast looked a bulky, girthed whale and a long-nosed dolphin. It was 50 feet long and tipped the scales at 30 tons. It lived about 200 million years ago.

DRACO LIZARD

Diminutive “Flying Dragon”

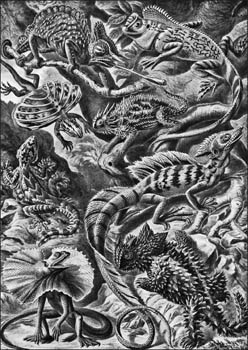

How scary to be a tiny lizard trying to make a go of it amid the eat-or-be-eaten jungle floor. Many lizards display bright colors to try to fool predators into thinking they contain poisons, even if they don’t. Or they count on camouflage, even changing colors; nevertheless, often none of this is enough to spare them from being consumed. The Draco lizard, found in the Philippines, Southeast Asia, and India, added flying to its survival tactics. The lizard has a yellow throat sac and yellow wings with a brown-freckled body but is only about 8 inches long, including its tail. Dubbed the “flying dragon,” the Draco has skin flaps or a membrane attached to its ribs, which grow away from its body and enable it to fly.

As lightweight as they are, some have been carried a mile when the wind is really blowing—carrying them far from any predator that had hoped to catch them. Draco lizards live mostly in trees, eating ants and termites, but the males have learned to use their gliding skills so well that they soar from tree to tree chasing other lizards away from their territories. A Draco female must come out of the trees and down to the dangerous forest floor to lay her eggs. She guards her eggs diligently for twenty-four hours and then abandons them totally before they hatch, never again to return to the nest. She is safer in the trees, and the brief time on the ground apparently scares her motherly devotion right out of her.

Lizard Double Chins

Many of the 400 species of Anolis lizards, such as the Draco, have expandable throat sacs, odd-looking skin flaps under their chins, which expand and pulsate seemingly with each breath. However, the sac is not an exterior lung or connected to breathing; it is actually called “gular skin” or a “gullar sac,” though commonly referred to as a dewlap. (Dewlaps, by definition, are any flap of dangling chin skin, which even some old men have.) On the Draco, its dewlap expands like a yellow balloon with the intention of making the lizard appear larger. It also acts as a sort of lizard Morse code, used for signaling and for communicating with other lizards. If a male has a bigger dewlap than others’, it usually claims more territory and attracts a greater number of females during mating season. The largest dewlap among lizards belongs to the Australian frilled lizard, which can inflate its throat and neck flaps to encircle its head, making it look ferocious and twice the size. The Draco can live for ten years, and the frilled lizard can survive for fifteen years.

After a running start or when perching up on a branch, the Draco unfurls its wing flaps and catches the wind to glide for more than 30 feet.

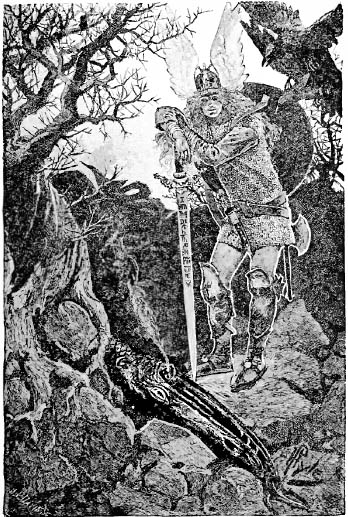

DRAGONS

Legendary Serpents

World literature is rich with stories and anecdotes about dragons. It was once thought that the “true” dragon was native to Ethiopia and India, or anywhere that had warmer climates. In India, dragons were said to be everywhere, with different species living in marshes, plains, and mountains. According to a Greek writer, Flavius Philostratus, they grew to “thirty cubits,” or around 55 feet long. The “marsh” dragon had silver scales, while the “plains” and “mountain” dragons’ scales were a golden hue. According to popular depiction, dragons had bony ridges running along their spines, and some had beardlike flaps of skin on their necks. Reptiles with wings, dragons had alligatorlike heads, four limbs (some had only two or none), and all were equipped with exceptionally long, thick tails. The size of tree trunks, dragon tails were used to beat, pummel, and coil around enemies, killing by suffocation. A dragon’s favorite food was the elephant, which it captured by tripping. Only some dragons, usually the ones that burrowed, had fire-breathing abilities, though all dragons inflicted the most havoc with their large and powerful tails.

Dragons lived in high, rocky perches, caves, or in deep subterranean caverns, and because of their size and ferocity, they were fearless, showing themselves as they wished in either day or night. Dragons did not fly for long distances, though they could achieve speeds faster than the swiftest river, and they usually were nonmigratory, staying close to the territory where they were born. They could soar to exceptional heights and usually gained altitude by widening the spiral of ascent. However, when spotting prey, a dragon descended from the clouds with the velocity of a falling boulder.

When Dragons Roamed

Evidence of dragons, a name stemming from the Greek words for “giant water serpent,” was frequently observed in the form of fossils or other remnants of huge animal bones, which we now know were from dinosaurs. However, since almost every culture has some reference to eyewitnesses seeing dragons, and with legends claiming they were around since man appeared, many think they were once real. Desmond Morris, a renowned zoologist and ethologist, speculated that what the ancients called dragons could have been various species of dinosaurs not yet extinct, which had, in fact, coexisted with humans.

Dragons’ eyes were thought to possess hypnotizing powers.

Famous Dragons

There are thousands of dragons cited in myth, but a few include: Apalala, an angry dragon that lived in the river Swat in Pakistan and was converted by Buddha to his religion of peaceful acceptance. After having killed his nemesis Grendel, Beowulf, an Anglo-Saxon warrior hero, died fighting an unnamed fire-breathing dragon, which inflicted a poisonous bite. Brinsop Dragon was a red-colored creature that lived in Duck’s Pool Meadow, in Britain, and was slain by Saint George. Fafnir was a Norse dragon that was originally a dwarf but was turned into a dragon by a magician. A small 9-foot creature called the Henham Dragon was seen flying around a British village in 1669. Ladon was a dragon of ancient Greece that guarded a special apple tree. Nessie, or the Loch Ness monster, is thought by some to be a type of dragon. Ouroboros is a dragon-serpent that eats its own tail and rebirths itself over and over. Puff the Magic Dragon lived by the sea and was featured in a song by the folksinging trio Peter, Paul, and Mary. Eingana is a female Australian Aboriginal dragon that is still alive and hiding; if she dies, the whole world will perish. Shen Lung is a Chinese good luck dragon and makes appearances at Chinese New Year celebrations.

DUNG BEETLE

Nature’s Smelliest Lives

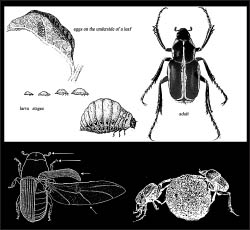

The dung beetle occupies a niche of the animal world few would consider appealing. There are more than 5,000 species of dung beetles found in all parts of the world, though not normally in icy or desert environments. They grow in sizes from 1/10 to 2½ inches and have metallic, shiny, shell-like bodies in either black, red, or brown, with some featuring one or two horns, plus antennae. Their job is waste removal, and they survive by eating the droppings or dung of larger animals. They do not need water or other food sources, getting all nourishment from excrement.

The dung beetle has an extremely keen sense of smell and can sniff a good, fresh pile of droppings miles away. Some can fly up to 10 miles and be on the dung moments after it splats. A variety of dung beetles hitch a ride on an animal’s tail, just waiting there in prime position to alight on a new deposit as it happens. Dung beetles are broadly categorized by the specialized methods in which they handle wastes: rollers, tunnelers, and dwellers.

The Rollers

This class of dung beetle likes to reshape animal waste and pack it into spherical balls. Rollers take apart animal feces and make one small ball of it and then continue rolling it around and around in the pile of feces, until the ball grows bigger and bigger—similar to how one would make the base of a snowman. Many roller dung beetles are extremely skilled at fashioning a perfectly round ball out of waste, a technique that allows them to transport their food source back to their nests. No matter where the dung ball is formed, they roll it back home in a nearly straight line, regardless of obstacles or distance, and navigate by moonlight.

The rollers are the strongest of the waste-removal beetles—they are capable of creating dung balls more than fifty times their size. Rollers are a rough crowd, and after a hefty ball is made, their biggest threat is getting it stolen by a larger dung beetle. Even so, the dung beetle will make and roll another ball, sort of like Sisyphus in Greek mythology, and not stop at its task of environmental cleanup for its entire life.

The Tunnelers

Certain dung beetles that have apparently tired of rolling balls instead make one quickly and then dig a tunnel close by and bury their prize. They never seem to forget where they stashed it. Some dung beetles will go into the burrow of animals and collect the waste, often making small tunnels within the burrow to store their dung balls.

The Dwellers

Other dung beetles simply live inside a pile of dung and do not bother to create dung balls or bury them. If manure is plentiful, a dweller beetle changes its dung-pile homes frequently and prefers to live in manure that has the most stench, which indicates it contains the freshest food source.

Life Cycle

Most dung beetles lay their eggs in specially prepared dung balls, which are then buried in chambers underground. Both the male and female will work together in excavating the breeding tunnels. A dung beetle goes through complete metamorphosis, with the larva eating the dung ball in which it hatched until it becomes a pupa, about three weeks after the egg was deposited. Two weeks later that beetle will breed, make as many balls as it can, and die usually in two months. Some species have life spans of one year, with the longest known to live for about three years.

Dung beetles will eat herbivore or carnivore feces, but they usually prefer the balanced diet offered by omnivore droppings.

Sacred Scarab

Ancient Egyptians admired the untiring dung beetle, called a “scarab,” and raised it to the importance of a religious icon. They thought that only male beetles existed and used the ball of dung as the womb for their offspring. Egyptians also thought that the sun was like a dung ball that each night disintegrated and needed to be remade every day. The scarab came to symbolize rebirth, and nearly all Egyptians wore amulets of the beetle. When a person died, jewelry fashioned like the beetle was often placed on the deceased’s chest.

DUGONG

Sea Cow

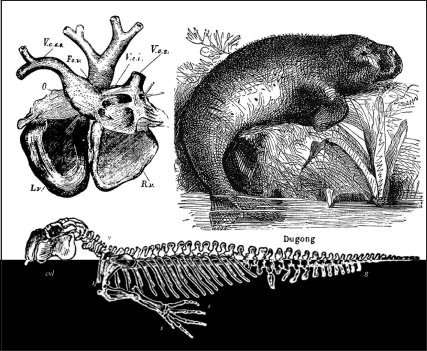

Found in the warm coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, and more abundantly off the northern Australian coast, the roly-poly dugong is a huge vegetarian marine mammal that resembles a tuskless walrus. Dugongs belong to the Sirenia family of animals, which has only four living species, including manatees.

It’s often argued that dugongs were the source for several mythological creatures, including the Greek sirens and even the mermaid (apparently seen by ancient sailors stricken with poor eyesight or blinded by loneliness). In African folklore, a sea cow was held as sacred, and many thought the animal had once lived its previous life as a human; killing it was considered murder. The 1,000-pound, 10-foot-long beasts claim the forebear of the elephant as their distant ancestor—not cows, though the first types did graze on land. The dugong returned to the sea about fifty million years ago. Manatees are much larger than dugongs, reaching 3,000 pounds and growing to 13 feet. Sea cows’ front arms are short and used to paddle, but their rear legs are no more than muscle stubs. Instead they use their flat, wide tails as their primary method for propulsion.

This tail, in addition to its thick bones and blubber, enables a sea cow to appear as if it is casually floating about sort of like an inflatable pool toy. As fat as they appear, sea cows are actually thick with muscle, yet they are incapable of ever leaving the water and cannot even roll themselves free if unexpectedly beached. Dugongs have big suction-cup-like lips, while manatees have more rounded snouts. Neither have biting teeth; instead, they have perpetually growing molars to grind their diet of aquatic grasses and sea plants.

Sea cows swim at a mere 3 miles per hour, but they can do quick sprints reaching 20 miles per hour if they must. They generally can hold their breath for about twenty minutes, though they like to sleep at the surface for longer periods of uninterrupted rest. Sea cows have no particular social hierarchy and prefer solitary lives, although mothers do form small groups and will swim with their young for almost two years. Males seem indifferent to territorial rights, but turn mean and become very aggressive when it comes time for mating. When migrating to find warmer waters, sea cows do loosely group together, but who is in charge seems not so important, and they play “follow the leader,” trailing whichever one decides to take the lead.

Life Cycle

Manatees and dugongs have no means of defense, and yet their size alone deters many predators, even if sharks and crocodiles attack occasionally. In modern times, pollution, red tide blooms of microscopic marine algae, and motor boat propellers are the main causes for the species’ dwindling numbers. Sea cows cannot hear the muffled noises made by boats; propeller blades give them fatal wounds by puncturing lungs and affecting buoyancy, thus causing them to drown. Fishing line, when ingested, blocks their digestive tracts and also kills them. When fortunate enough to avoid these hazards, dugongs and manatees can live for about sixty-five years.

A sea cow has elongated lungs that stretch the length of its spine and, like internal airbags, are used to help regulate buoyancy.