HALLUCIGENIA

Evolution on Acid

From what strange dreams of nature were the first creatures formed to produce a wormlike animal with seven pairs of pincer legs, six sets of tentacles across its back, and a blob of a head without eyes, ears, or mouth? Meet the hallucigenia. This tiny inch-long animal had a psychedelically purple and Day-Glo yellow-orange tubular body, as well as multicolored legs and tentacles. Its shape seemed improbable for locomotion, lopsided as it was, with stick legs that were actually curved spines, designed to making walking a clumsy endeavor.

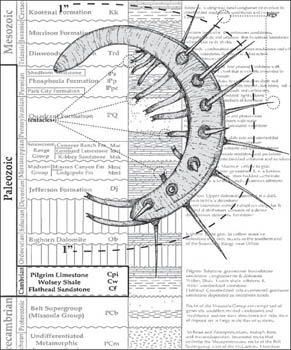

Hallucigenia, so named for its bizarre and dream-like quality, emerged during what paleontologists called the “Cambrian explosion,” five hundred million years ago, when new creatures were appearing in staggering numbers. This prehistoric period seemed guided by an experimental artist scribbling out sketches and weird animal designs at a furious pace, tossing page after page of biological blueprints into the wind, sea, or land and waiting to find out what anatomical feature worked best. Hallucigenia might have developed or converged into arthropods and spiderlike animals, though no creatures that remotely resemble it exist today. However, today cutting-edge robotic engineers are using the multilegged hallucigenia as a model for mechanical devices able to crawl over all surfaces without toppling.

It is not known if the creature had small, chewing mouths at the end of each leg, or if the food it captured was handed off from one pincer to the next like a baton in a relay race and then inserted into an eating hole somewhere near its blobish head.

Evolutionary Convergence

Certain animals that have no genetic connection independently develop similar characteristics, such as the wings of birds and bats. Scientist Simon Conway Morris, who named the hallucigenia, said, “all organisms are under constant scrutiny of natural selection [and] the organic substrate we call life [is] really a search engine to discover particular solutions.”

HALCYON

Bird of Spring Break

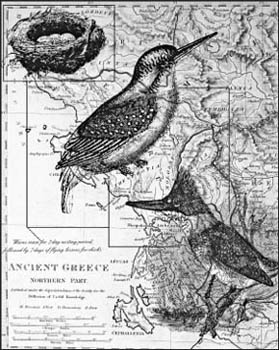

Even the ancients appreciated a spring break. The Greeks viewed any unexpected week or two’s reprieve from winter to be miraculous and attributed the nice weather to a bird called the “halcyon” that laid its eggs on the shore. They thought this unusual bird rarely came ashore and normally lived far out at sea. However, it always chose a week in midwinter for hatching its offspring. It took seven days for the mother halcyon to sit on her eggs, at which time, winter’s crashing waves abruptly ceased.

Was It Real?

Descriptions of this mythical bird seem to fit a real bird called the kingfisher, which has the genus name Halcyon. Kingfishers are generally medium-sized, colorful birds with long, thick bills. Certain species of kingfisher inhabit coastal regions and use their pointed bills to spear fish. They also dig out burrows near the waterline to lay eggs. The brief hatching period attributed to the ancient halcyon does have some basis in the habits of many shorebirds, which tend to have shorter incubation periods than those of many terrestrial bird species. The ancient halcyons were immortal, but the kingfisher usually lives for about seven years.

When an unseasonably warm spell occurred, sailors and all the ancient populations shook their heads knowingly, and referred to them as the “Halcyon days,” and were sure winter’s rage would not return until the halcyon chicks, nesting on some secret coastline, were old enough to fly. “Halcyon days” is a phrase that is still used to describe any unexpected pardon from the daily grind—or a nostalgic longing for the easy, carefree days gone by.

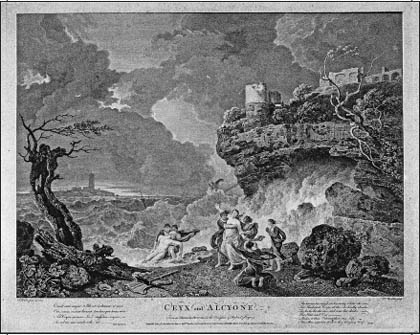

Lovebirds

The legend of the halcyon grew from tales in Greek mythology about two lovers, Alcyone and Ceyx, who adored each other more than Zeus, thus angering the chief god. Accordingly, Zeus killed Ceyx by sinking his ship with a lightning bolt. When Alcyone heard of her lover’s fate, she tossed herself into the sea. But their deaths were pitied by the other gods, who decided to transform the lovers into birds—the halcyons. Since Alcyone’s father was the god of the winds, he honored his daughter each year by commanding the winter winds to cease and the waves to calm as the halcyons’ eggs hatched.

HARPY

Hazardous Hovering Hag

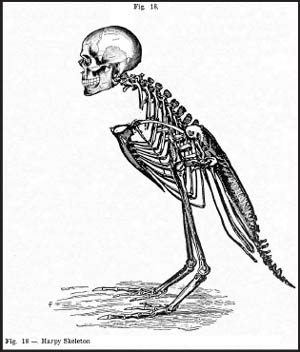

According to Greek myth, harpies were unpleasant creatures with bloated eagle bodies with broad wings and sharp, fingerlike talons. A harpy’s features were entirely birdlike, except for a human, female face. Harpies were fast fliers and appeared from nowhere to wreak havoc. In rare accounts, a harpy was attractive, though it was usually described in most legends as being extremely ugly.

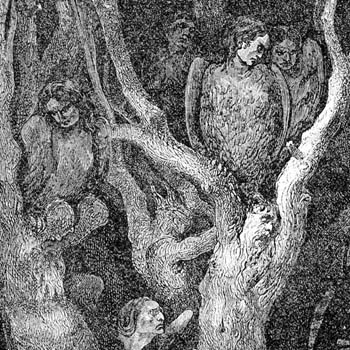

Whenever harpies are mentioned in literature or mythology, they are always cruel and violent. Phinas, a king who revealed too much information about godly secrets, was sentenced to attend a lavish all-you-can-eat buffet. However, the moment he tried to take a bite, harpies stood guard and snatched the food from his hands. The poet Dante had harpies tormenting persons who had taken their own lives in the fourth circle of hell. The victims were encased in an oak tree, but just as the leaves bloomed, hovering harpies swooped in and ate the buds, so that the entrapped souls remained hungry forever. After Shakespeare used harpies to describe women who were nasty and malicious by nature, the phrase “to harp on” came to mean to dwell incessantly on the same thing.

HELICOPRION

Buzz-Saw Shark

This prehistoric sharklike fish stands out in the catalog of strange creatures for having a disk-shaped lower jaw with teeth arranged in a spiral pattern, looking nearly identical to the blade of a circular saw. At 15 feet long, the helicoprion prowled the world’s oceans 225 million years ago. It had a pointed snout like a shark, but its bottom jaw featured a coil of vertically aligned teeth. As new teeth grew, older ones didn’t fall out but were pushed back like the steps of a circular staircase, until some of the fish had a lower jaw as wide as a 3-foot saw blade. It seemed to use its peculiar jaw structure as an effective killing technique—sort of like a chainsaw massacre of the ancient oceans, plowing through schools of fish, dicing and slicing as many as it could strike and then circling back to gobble up its wounded prey.

Scissor-Mouth Shark

Another prehistoric shark, called the “edestus,” also held on to its teeth, as opposed to shedding them and growing new ones as do modern sharks. This beast was equally as ferocious as the helicoprion, though it grew a longer and longer jaw and snout to accommodate each new season’s crop of razor-sharp incisors. Its deadly mouth eventually looked like a pair of giant serrated scissors, similar to the type used to cut fabrics, but it was powerful enough to fashion its prey into bloody tidbits.

HAMSTER

Domesticated Rodent

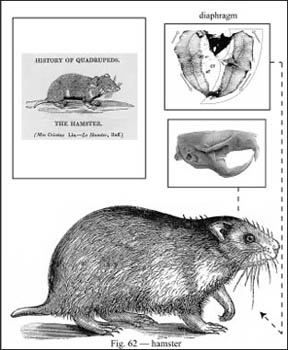

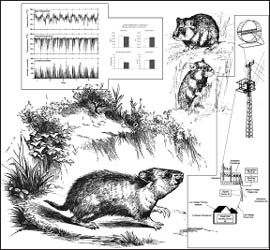

Saved from near extinction by its cuteness, the golden hamster now is among the top five favorite pets in the United States. This is quite an accomplishment for a short-tailed rodent weighing approximately 8 ounces and standing less than 6 inches tall on its hind legs—especially considering it was first domesticated only in the 1930s and introduced in the United States in 1938. Hamsters were rarely observed in the wild, naturally living in remote, semi-desert regions of Asia, Africa, and Central Europe. Many thought the animal a tailless mouse, although it was eventually identified as a unique species in 1839. Little was heard of the hamster until nearly one hundred years later, in 1931, when a zoologist wanted to know if this species still existed and went into the Syrian Desert in search of the tiny beast. He captured a litter, but only a brother and sister survived. This single pair, however, came to provide the ancestral breeding stock for generations of pet hamsters to come. Nearly all hamsters sold as pets are descendants from the first brother and sister pair captured more than eighty years ago. More than 1,000,000 golden hamsters are sold annually, but only 10,000 hamsters (excluding escaped pets) are left living in the wild.

The Wild Hamster

Fossils indicate hamsters first appeared in the Middle Miocene epoch (16 million to 11.6 million years ago) and developed unique survival skills. Hamsters are burrowing animals and can make elaborate underground sanctuaries more than 30 feet in length, with rooms for sleeping, chambers for socializing, and other compartments for food storage. A hamster adds numerous escape routes and can squeeze into any cracks as long as its head fits. The rodent often nudges a rock over the exits to dissuade unwanted visitors, but also uses the entry stone to collect morning dew, lapping the few droplets of water it needs to make it through the day.

Hamsters are fussy about keeping their fur clean and groom themselves regularly. In the wild, hamsters spend infrequent time aboveground, emerging at sunset and dusk, though sometimes they gather food during the day. They have entirely black bulging eyes, which makes them farsighted and virtually blind in full light. A hamster cannot see objects up close, like a hand thrust in its face, and it will bite at such objects as a reflex. Hamsters do not hibernate, but when subjected to extreme heat or cold, they lower their heartbeats and metabolisms so as not to need food or water for a few days, hopefully until the severe weather passes.

Life Cycle

Owls, foxes, and snakes are hamsters’ natural enemies in the wild. Pet hamsters are susceptible to a number of diseases, including stones in the bladder and numerous kinds of cancer, which especially afflict the females of the species. Starvation from neglect is an all-too-common demise among caged pet hamsters. Hamsters also get an intestinal disease called “wet tail.” In addition, they may die of salmonellosis acquired after consuming tainted packaged seed mixtures, and they can transmit the bacterium to humans who don’t wash hands after handling their hamsters. A sick hamster will let its fur go unkempt, and its bright eyes will become dull.

No permits are required to bury a deceased pet hamster in your backyard. Band-Aid tins and Ovaltine jars often served as coffins for children’s deceased pet hamsters during the 1960s and 1970s, but now there are pet cemeteries and crematoriums available to give hamsters full rites, including headstones or urns. Hamsters usually live no more than two to three years, though some have reportedly lived up to five or six years.

Hamster Ban

In 2008, during the Zodiac Year of the Rat, owning pet hamsters became a hugely popular fad with Vietnamese youth. Fearing an explosion of runaway hamsters wreaking havoc on crops and acting in precaution against the spread of diseases, government officials banned owning hamsters. Many boys and girls kept their pets in secrecy, and an underground hamster culture grew.

Saddlebag Cheeks

Hamsters are diligent hoarders, and some wild hamster burrows were found to have more than 50 pounds of stored edibles. Hamsters have elastic-like cheeks that are used to carry foods while foraging. A hamster’s cheeks can expand to such an absurd size that it would be equivalent to a person stuffing two soccer balls in his or her mouth. In Arabic, the Syrian or golden hamster was called “saddlebags” for its ability to pack its mouth pouches so well.

Alternative Power

With a million hamster wheels spinning on any given night, it’s been speculated that the collective energy of hamsters could light a small city, if all were hooked to the power grid.

Double Dipping

Hamsters, like rabbits, have stomachs that are not quite cable of digesting certain grasses and grains on the first eating. As a matter of course, they practice “coprophagia,” a term meaning they eat their own feces or droppings. They do this to get the nutrients that were missed on the first go-through. Hamsters seem to feel no embarrassment when chewing on their own pellets.

HORNED LIZARD

Minister of Defense

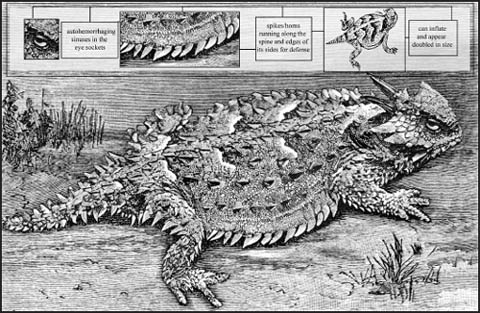

Mistakenly called a “horny toad,” this curious-looking creature is, in fact, a lizard and not a toad. The horned lizard does have the brownish coloring of a toad and squats close to the ground, but it has four similar-sized, scale-covered legs and a thinly tapered tail—and it does not hop. It also has distinctive spiky thorns that run along its spine and at the edges of its sides, with three or four larger horns crowning its head, giving it a gladiatorial appearance.

There are 14 species of horned lizards in total, with most types found in North America, predominately in desert or semi-arid climates. They grow 4 to 8 inches long. When threatened, the most unusual of the species can instantaneously inflate itself, puffing up into a spiked ball that is twice its normal size. When that fails, it can squirt blood from the corner of its eyes, thoroughly freaking out the most persistent coyotes or wolves. The horned lizard can spray streams of red blood (which is foul smelling to boot) up to 4 feet.

Life Cycle

A horned lizard primarily eats ants and makes a zigzag line from mound to mound. This food choice leaves the reptile wide open to many attackers, including snakes, roadrunners, hawks, and carnivorous mammals.

Even with all their defenses, food is scarce in the desert, and horned lizards are easy marks at birth and remain vulnerable to predators until they grow and develop their unique military protections. Some species of horned lizards lay more than forty eggs at a time to enhance their species’ survival rate. The new hatchlings immediately bury themselves under sand and receive no guidance from their parents. Horned lizards can live in the wild from five to eight years.

Strong Medicine

The great cataloger of Mexico’s animals and plants, Spaniard Dr. Francisco Hernandez, was amazed when he observed the horned lizard, and he shocked European audiences when his writings about the creature were published in the mid-1600s. Native people of the North American Southwest and Mexico had long held the horned lizard in high esteem. Shamans and medicine men chanted about the character of the lizard to an ill person and sometimes placed one of the scaly specimens alongside the sick. It was thought that the tough and resilient spirit of the horned lizard would cure the infirm. When missionaries arrived in Mexico, they also liked the horned lizard and thought it was a holy beast that wept sacred tears of blood.

HORSE

Civilizing Steed

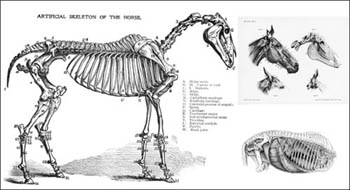

There are 75 million horses in the world, grouped into more than 400 different breeds. Horses were first domesticated about four thousand years ago by nomads of the Asian steppes. The earliest horse ancestor was a fox-sized animal that appeared fifty million years ago. Many evolutionary breaks and branches occurred until the long-legged genus Equus—which today consists of horses, asses, and zebras—appeared a mere five million years ago. Horse history and its evolution are the most documented of animals, since, before the invention of the engine, the horse was entwined with civilizations’ rise and fall. Those who had horses ruled, and it was a well-known proverb that you could judge a man by looking at his horse.

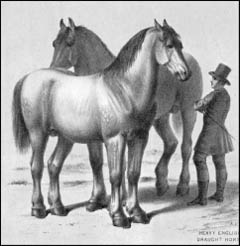

A Horse Is a Horse

Horses come in all sizes and are specialized at various skills. One of smallest horse breeds, the Falabella, measures around seven hands or about 30 inches from it hoof to its shoulder (called its “withers”). The largest, the Belgian Brabant, stands at seventeen hands and weighs more than 2,000 pounds. The towering Brabant, incidentally, eats 60 pounds of hay each day and drinks 20 gallons of water, and it is strong enough to pull a load four times its weight, or as much as a school bus filled with kids.

One horse breed, called Przewalski’s, is thought to be a remnant of the true wild horses that once roamed the Mongolian—a kind that were never domesticated. The last wild ones were seen in the late 1960s, though attempts to reestablish a free-range population are under way. In the wild, horses roamed in herds of about twenty, led by a dominant male or “stallion.” A female horse is called a “filly” or “mare” and the young are called “foals.” Horses’ baby or “milk” teeth fall out between the ages of three to five years, and they keep their mature teeth for the remainder of their life. Before record keeping, the age of a horse was gauged by examining its teeth. Horses are naturally herd animals and prefer to be around members of their own kind. Horses usually get along with other livestock, but many are known to dislike the smell of pigs.

Horse Sense

Since horses have been a part of our culture for so long, many phrases have been inspired by our dealings with them. The term “horse sense” refers to one who has a commonsensical knowledge and originally referred to a person adept at looking at a horse and discerning its qualities and flaws. The Greek writer Xenophon published a treatise in the fourth century B.C., “The Art of Horsemanship,” which taught “horse sense” and included practical techniques to avoid buying a bad horse. Like many animals, there are no two horses that are the same, as each individual displays various preferences and personality quirks. Horses have a unique intelligence and possess exceptional long-term memories. Yet they can also be spooked by nearly anything, often by the sight of such ordinary objects like a plastic bag tumbling in the wind. They then run recklessly to avoid whatever they think of as dangerous, since fleeing has always been their primary defense to avoid mishap. Horses live, on average, for thirty years.

Horse “Hands”

Horses are still measured in “hands,” equivalent to about 4 inches, or the distance from the tip of the outstretched thumb to the top of the pinky finger. This is an ancient measurement system, probably established by Egyptians making pyramid calculations and eventually applied to the commerce of horse trading.

Gift Horse

“Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth” is an idiom from the days of horse trading, when the wear and tear of a horse’s teeth indicated its age and how useful it would be for working the field. If someone gave you an old horse for free, it was impolite to look at the teeth of the gift horse before accepting it. Doing so would be similar to checking out the price tag of a birthday present before accepting it.

The famous TV “talking horse,” Mister Ed, starred in a sitcom during the 1960s. The blond palomino, a gelding by the real name of Bamboo Harvester, displayed an uncanny ability to act, completing such tasks as turning on a light switch, unplugging wires, and stomping its feet on command. But like many actors, he was also temperamental and refused to work when he didn’t feel up to it. To get Mister Ed to appear to talk, a grainy treat with the texture of peanut butter was spread on the horse’s gums.

HUMMINGBIRD

World’s Tiniest Bird

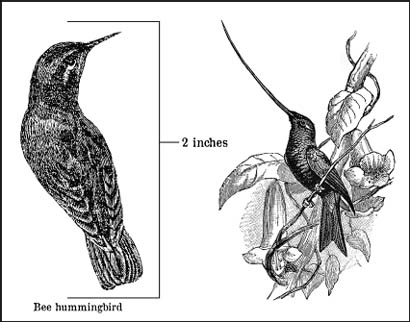

The immortal gods drank nectar. So too does the hummingbird, the smallest species of bird in the world, specialize in drinking the sweet, syrupy resin secreted by flowers as its primary food. The gods had the drink delivered by doves as they lounged on their cloudy cushions in the sky, but the hummingbird works incredibly hard to get its daily fill. The small bird must sip a dew-drop amount from more than one thousand flowers in a four-hour period just to sustain its supercharged metabolism, needing to consume half its body weight by this labor-intensive method every day. There are more than 340 different types of hummingbirds found throughout North America and South America, and all are usually as colorful and iridescent as the shades of flowers from which they feed. The smallest, the bee hummingbird, is the size and weight of a walnut, or about 2 inches long, while the largest, the giant hummingbird, measures about 8 inches, though this bird is also extremely thin boned and bodied, weighing only 2/3 of an ounce.

A hummingbird can fly up, down, and backward as well as hover by doing a figure-eight motion with its wings. It can migrate for distances of thousands of miles, reaching cruising speeds of 30 miles per hour and can also achieve short sprinting flights of nearly double that rate. The hummingbird’s tiny heart beats more than one thousand times per minute. In addition, it takes a hyperventilating rate of breaths needed to maintain this effort, inhaling and exhaling more than 250 times every sixty seconds.

Flower Dance

Orioles, finches, and even woodpeckers might take a dip of flowery nectar, just as hummingbirds, likewise, might alter their diets by eating bugs while hovering at an open petal.

The flowers hummingbirds feed on have indeed adapted to this prolific pollinator, with some plants evolving new petal shapes and different carpels (the part that holds the nectar at the base of the petals) to accommodate hummingbirds. Similarly, hummingbird bills have modified to various lengths and curves so the birds can get nectar from their favorite flowers more easily. The flower and the hummingbird have been in an evolutionary dance, both altering as the climatic music changed with each environmental shift. The hummingbird, as tiny as it is, however, is a feisty bird that earnestly protects its flower patch against all kinds of other birds, rival hummingbirds included. This little bird has no problem going face-to-face with a mighty hawk, if necessary, nearly always outmaneuvering it with its hovering, aerial skills, and dronelike speed. Sometimes a group—called a “charm”—of hummingbirds, are seen taking a momentary break in bushes near flower fields, but the bird is never observed on the ground; the feet of a hummingbird are good only for perching and of no use for walking.

Life Cycle

The task of nectar hunting does not afford the hummingbird immortality, as it did the mythical gods. At the end of each day, its frantic working life sends the bird into a sort of hibernation, much more profound than sleep, called “noctivation.” Each night it touches the borderline of death, when its metabolic rate is slowed by as much as 95 percent.

In this state, the hummingbird’s lungs move almost undetectably and the bird can be touched and picked up, seeming lifeless. In the morning, its arousal back to life takes nearly twenty minutes before it returns to normal and begins its day of searching for nectar. Hummingbirds live on average from three to five years. One hummingbird will flap its wings approximately 210,240,000 times during its lifetime.

The hummingbird is named from the sound its wings make, flapping at an eye-blurring speed of more than fifty times per second.

—

Recent finds in Germany revealed a thirty-million-year-old hummingbird fossil. The question of why none remain in Europe or Asia is unanswered.

—

Ecuador is the hummingbird capital of the world, with more than 160 different species found in that country alone. The rufous hummingbird migrates the farthest, traveling 3,000 miles from Alaska to Mexico each year.

HYDRA

Many-Headed Mythical Monster

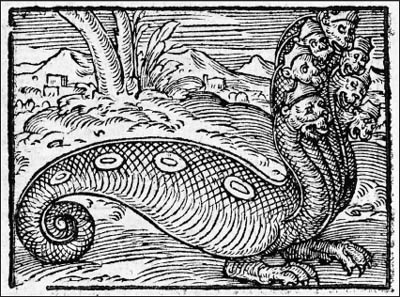

This multiheaded serpent lived in the swamps near Lake Lerna in ancient Greece and was believed to be real by the local populations for more than two thousand years. If it was a dinosaur of some sort, no fossils were found to prove it, yet the Greeks thought this beastly anomaly was an offspring of various gods or Titians. Nevertheless, according to ancient sources, this reptilian creature had a hefty body covered with scales and a long, curling snake-type tail. It also had two clawed feet, or four feet in some versions, and was either the size of a baby elephant or as massive as a dragon. In addition to an ensemble of sharp-toothed mouths, it emitted a foul, poisonous breath.

How to Kill a Hydra

In stories, the hydra became a nightmarish symbol of any seemingly insurmountable problem that only got worse no matter what you did. Legend said the hero Heracles finally defeated it by compartmentalizing the problem. Although he kept an eye on all the heads, he cut one off at a time while instructing his assistant, Iolaus, to shoot a flaming arrow at the neck wound, cauterizing (or sealing) it with burned flesh to prevent a new head from blooming. The final hydra head could not be resolved with any weapon, so Heracles pulled it off with the brute force of his hands and buried it beneath a rock.

One of the hydra’s unique qualities was instantaneous regeneration. If a hydra head was cut off, not one, but two heads grew back to replace it; depending on accounts, the hydra could have anywhere from nine to one hundred heads.

Autotomy

Lizards and lobsters can spontaneously self-amputate a limb, a tail, or a claw when under attack in a process known as “autotomy.” This adaptation helps a lizard to escape, as it hopes a predator will seize its wiggling tail and allow it time to flee. Some lizards have the ability to regrow their lost body parts, especially their tails. A lizard can regenerate its tail as many times as it is cut off, though each new tail grows back shorter and shorter. The original tail consists of vertebrae that are an extension of the lizard’s spine, but the vertebrae do not grow back in the regenerated versions—instead, a similar-appearing cartilage manifests. How this happens, biologically, remains a mystery. As for head regeneration, the hydra is the only beast said to accomplish such a feat.

HYENA

Merry Matriarchal Marauders

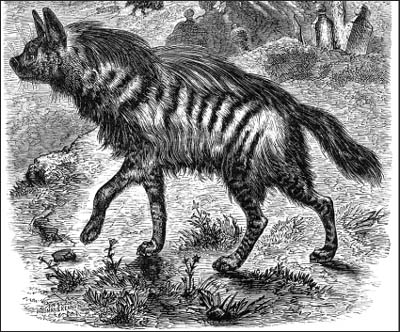

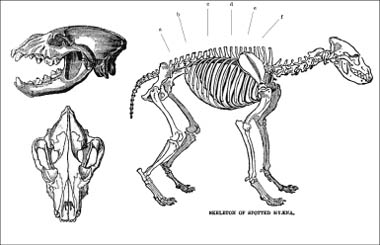

Hyenas are found in Africa, Arabia, and India, adapting to a variety of terrains, from grasslands to mountains. Their range once spread though Europe and much of Asia. There was even an extinct type that lived in North America at the end of the last Ice Age. Hyenas are similar to many doglike species that form social packs for hunting and catch prey with their teeth rather than by claw, yet their evolutionary trail shows they have more genetic similarities to prehistoric cats.

Although branded with a reputation as being scavengers, hyenas are clever and determined hunters, obtaining more than 95 percent of their daily food on their own. Nonetheless, even lions frequently abandon their kill without a fight when surrounded by a large group of hyenas. There are three species of hyenas; they all have small heads with short muzzles and bone-crushing teeth, dark fur around their eyes, ears that stand upright, and long, thick necks, giving them a distinctive silhouette among animals. The largest, the spotted hyena, grows to nearly 5 feet long and weighs as much as 200 pounds.

Females Rule

The mama hyena rules the clan, which can have as many as 80 members in one cackle. All are singularly focused on protecting their territorial rights. A female earns rank by fighting and rules according to the power of her jaw and her cunning. Even the lowest-ranked female in a hyena clan is above the strongest male. When it comes to dining, hyenas will even mortally injure one of their own if they think another is trying to skip the line in the established hierarchy. Hyena clans are fluid, and alliances change frequently, but all will rally when called to protect their dens—especially when ganging up on lions and big cats.

Why Does a Hyena Laugh?

Hyenas, as social animals, developed a complex system of vocal communications that enable them to excel at working together. Their infamous laugh—more like a cackling giggle—is used when they are either frustrated or nervous. They also make an extremely loud whooping sound that can be heard for miles and is employed as a siren, calling all hyenas to gather for an attack. This war cry arouses their adrenaline, and few can resist it. A hyena’s rank determines the type of laugh: the less-dominant ones laugh more frequently and at a higher pitch.

Are Hyenas Evil?

African legends about hyenas often associated them with demons. Witches were believed to be the only ones able to train hyenas. Evil shamans could summon these beasts to do their wicked deeds. Other cultures considered hyenas as couriers to the spirit realm. Hyenas were said to rob graves to snatch the souls away to hell. But not all thought hyenas possessed evil magic: among the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania, it was customary to leave their dead out in the open, and they believed it honorable for a human carcass to be devoured by hyenas.

Life Cycle

Laughter is often said to be the best medicine, and for this animal, it seems to increase its life span; that is, if it survives birth. Nearly 60 percent of firstborns suffocate in the birth canal, and only about half of the young make it through the first year. Afterward, their powerful social network provides a long life in the wild. Among hyenas, to be born from a governing female is sort of like the passage of royalty among humans, because this high status will ensure protection from other hyenas and access to more food. Hyenas live for about twelve years, though some reach the age of twenty or older.

Gender Bender?

For centuries, hyenas were thought to be capable of changing their sex or were considered to be hermaphrodites (containing both female and male reproductive organs). In part, this misunderstanding was due to the prevailing role of the female, which many early naturalists assumed was a male—but they were at a loss to explain how the pack leader was capable of giving birth. Dominant females have extra supplies of hormones that make them aggressive, but also make their sexual organs form into odd, elongated shapes that appear extended somewhat similar to males’ private parts. Giving birth through this curious narrowed birth canal gave rise to myths claiming the male hyena gave birth.