IBIS

Sacred Snake Snatcher

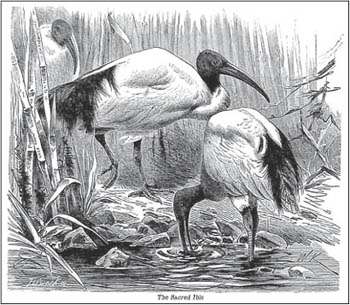

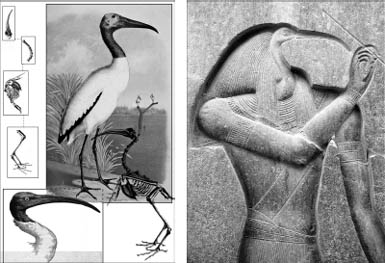

The ibis, a long-legged shorebird with a sickle-shaped, down-turned bill, was hailed in the Bible and in Egyptian writings as the perfect animal to rid an area of snakes. Ibises are experts at catching any number of amphibians, reptiles, and crustaceans; they usually wade in a group (or a “siege”). As if telepathically connected, all become motionless simultaneously. Sometimes a few ibises wade farther upstream in order to drive fish toward ibises waiting nearby along riverbanks, shorelines, and in estuaries, where they normally feed. In ancient times, snakes were no minor ecological problem and accounted for tremendous fatalities; oftentimes, areas overrun with snakes were abandoned from settlement. The ibis, as a deliverer from these creatures, rose in status until the bird was made sacred within Egyptian mythology. In the story of Noah’s ark, the ibis was among the first birds released, perhaps to catch any snakes remaining after the Great Flood.

There are nearly 30 different types of ibises found in the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. They nest in colonies and sleep in trees at night. All are strong and graceful fliers, and they are not usually territorial. In fact, ibises often feed alongside other wading birds. They particularly like to hunt near taller herons, as both birds help one another in some ways. A group of foraging ibises frequently drives food toward the solitary heron, while the taller bird’s height advantage gives the ibis flock an early warning system when raptors or birds of prey are about. The ibis, depending on its environment, is food for carnivorous birds, big cats, or crocodiles. On average, ibises lives for around twenty years.

The African sacred ibis is white, with a black onyx head, beak, and legs. There are black tips at the end of its white wings and on the tufts of its tail feathers. This majestic bird has a 2-foot-long body with wide wings spanning nearly 4 feet. In Egyptian theology, a principal deity, Thoth, was often envisioned as a man with the head of an ibis. The god had many roles, from the inventor of writing to judging the dead. The bird was considered so holy it was frequently preserved as a mummy. In one vast, ancient burial ground, or necropolis, near the city of Memphis in Egypt, archaeologists found more than half a million mummified ibises.

The American white ibis was chosen as the mascot of the University of Miami since it was cited by the public relations committee as a brave bird. When hurricanes approach, the white ibis is the last to seek shelter—which may not be the best idea—however, it is the first bird to return, signaling the storm has ended.

IBONG ADARNA

Songbird with the Rudest Surprise

According to local legend, there once was a bird living in the Philippines that was extremely rare—and dangerous. Even so, the ibong adarna, as the bird was called, was sought for its healing powers, because it was believed to be a curative for depression. The bird, about the size of an eagle with a long peacock tail, always sang seven exceedingly melodious songs, all in a row. After each song, the bird’s feathers changed into entirely different colors. Anyone who heard the music fell into a sound sleep. To avoid capture, the bird then perched above the sleeping suitor. It would find the right position, aligning itself just so on a branch and then defecate on the person’s face. Its excrement was of a chemical concoction that induced a long-lasting coma. The bird’s spell could be reversed with a mere bucket of water thrown into the face to wash off the bird’s droppings. Despite extensive hunts for this magical bird, none have been spotted in modern times.

ICHNEUMON

Dragon Slayer

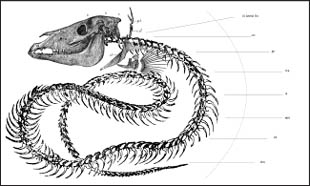

In medieval lore, the ichneumon was an expert dragon tracker that hunted the monsters in their lairs with the steadfastness of a bloodhound. Descriptions of the beasts are similar to those of weasels or otters, which are also slender and agile furry mammals. The ichneumon seemed to have an inherent hatred of dragons and prepared for battle with the giant beasts by covering itself with mud. It would wait as one layer of mud hardened and then repeat the process until its coat was as thick as armor. The ichneumon then stalked a dragon and waited until it was in a deep, snoring slumber. It killed the mighty dragon by climbing onto its head and then burrowed into the beast’s nostrils, weaving itself into one and then coming out head up from the other nostril. This method suffocated the dragon while it slept.

The ichneumon also slew crocodiles in an equally creative manner. It waited until the reptile opened its mouth to allow birds to enter and pick its teeth clean. The ichneumon then snuck in and crawled down the croc’s throat, burrowing and chewing through the reptile’s intestines until the beast died. It then emerged unscathed from the crocodile’s nether region.

What Was It Really?

It seems more likely that ichneumons were inspired by actual mongooses, noted as expert killers of dangerous snakes. Although not related to weasels, they look alike and are found in Asia, Africa, and Europe. The Indian mongoose is legendary as a cobra killer and a likely source of ichneumon folktales. A mongoose is quicker than a cobra strike, and it uses cunning and trickery to defeat the venomous reptile. The mongoose has also a natural built-in resistance and immunity to snake toxins. However, it doesn’t eat the snake but usually attacks in a preemptive assault, in order to hunt for its diet of rats and small rodents without competition, or to avoid worrying about getting caught unaware. Mongooses grow from 1 to 4 feet long and would have easily qualified as the medieval dragon slayers of old.

There’s a superfamily of insects, named Ichneumonoidea, that contains more than 80,000 species. Ichneumon wasps have long and thinner bodies than bees and have veiny wings. They have what appear to be very long stingers, but they are actually the females’ egg depositors. The wasp pierces the body of any number of insects and lays its eggs inside. As its larvae grow, they feed on the host until they kill it.

INKANYAMBA

Zulu Monster

This fabled creature is a 30-foot eel with fins protruding from its horse-shaped head. Like many cryptids—creatures that lack scientific explanations—this one lives in a specific location, namely Howick Falls in South Africa. Zulu folklore describes the inkanyamba as swift and ferociously carnivorous, known to snatch people and animals from the shoreline in the blink of an eye. It usually only surfaces from its deep underwater caverns during the summer months and especially during torrential rainstorms.

Since such a creature was found among prehistoric cave paintings, alongside depictions of known animals, this evidence gives rise to the possibility that some type of large eel once existed in the area. There is an eel called an “anguilla” that grows to about 6 feet. There is also a living specimen of an eel-like creature, called a “hagfish,” which is found in African waters. The hagfish, which is neither a true eel nor a fish, does, in fact, have a slimy and snakish anatomy. It has a skull with two brains, but lacks a spine, and yet despite these oddities, it has never been seen leaving the water or swimming in the clouds.

During hard downpours, the inkanyamba can rise out of the water and ride in the clouds of the storm, gobbling up people miles from its normal waterfall environment.

IMPALA

Spring-Loaded Savannah Sprinters

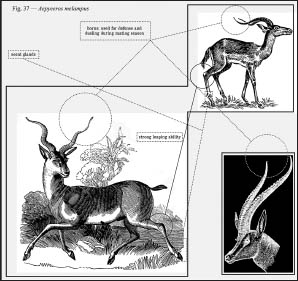

This swift antelope lives in the African savannah and gathers in huge herds, numbering in the hundreds. The impala stands about 3 feet at the shoulder and weighs 100 pounds. The males have long and sharp spiraled horns, which are used as part of their defensive tools—and for dueling when challenging each other during mating season.

When outlying members of a herd see danger, such as stalking lions, an impala calls out in a dog-sounding bark to warn the others, signaling an adrenaline-charged stampede. The herd can go from a standstill to speeds of more than 50 miles per hour in an instantaneous explosion of leaping antelope. They use this bark sparingly and seem to have an unwritten code to never “cry wolf” without good reason.

Spring-Boarding

The characteristic that distinguishes the impala among antelopes is its remarkable broad-jumping capabilities. Just as a lion is about to grab it, the impala can leap for a distance of 30 feet. The impalas’ seemingly patternless leaping and bounding to the right or left totally confuses would-be predators, yet there is a hidden organization in this pinball type of motion among the fleeing herd. While in midflight impalas release scents to signal to others the general directions they all are to follow, thus keeping the herd moving on a similar course. But with such a springy-footed skill, impalas often leap for the fun of it and can jump up into the air as high as 10 feet. They often use this agility to jump over instead of walking around bushes that might seem too prickly. An impala lives on average for about twelve years.

Impalas, like many grazing herbivores, epitomize nature’s law that there is often greater safety in numbers.

ISOPODA

Pillbug

Isopods are truly ancient creatures that have remained nearly unchanged for three hundred million years. They are crustaceans with hard shell-like bodies and usually have seven pairs of legs. More than 5,000 species of isopods live primarily in the ocean, but a nearly equal amount traverse the land. A common terrestrial version, known as woodlice (though also called “pillbugs” or “roly-polys”), is found in temperate climates all over the world; woodlice are easily seen by upturning a stone or a fallen tree.

The Round Defense

When poked with a stick, woodlice roll themselves into a perfectly shaped pill-sized ball. In reality, they are not an appetizing food for many, since the bulk of their bodies consists of a hard exoskeleton, which holds their form together just as skeletons define and hold the structure of internal organs and tissues of other animals. Pillbugs do not need to find new shells and instead shed theirs as they grow by molting and growing back larger ones.

In addition, pillbugs have no way to regulate their body temperatures and internally assume the temperature of the environment around them; however, they can also hibernate when cold weather approaches. Pillbugs are not poisonous and carry few diseases harmful to us. They prefer the dark world under tree bark and eat decaying vegetation, living on average for about three years.

A pillbug needs a lot of moisture and dampness to survive and dries out quickly, turning permanently into a dried ball of a bug when conditions become arid.