INTRODUCTION

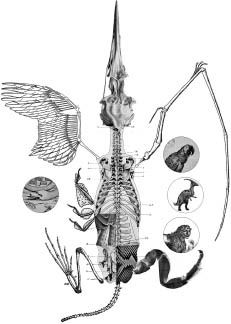

The first bestsellers were medieval encyclopedias called “bestiaries” that described strange and fascinating facts and lore about animals, real and imagined. Often gorgeously illustrated, they were less products of close observation than works of imagination, myth, or the rare traveler’s tales of far-off lands populated with seemingly fanciful creatures. Griffins and unicorns thus were comfortably included alongside eagles and lions. Beasts were studied to see what lessons they could teach us—about daring and sloth, loyalty and cowardice, good and evil. Early naturalists and philosophers looked to animals as a way to measure our differences, defining ourselves by similarities or by observing the wide range of peculiarities found in nature. Then, as now, animals spurred our imaginations, occupying our dreams and nightmares. Real and mythical creatures were anthropomorphized, given human qualities as a means of making points about mortality and ethics. Eventually, the study of animals spurred serious scientific inquiry and helped establish an understanding of biological laws and principles.

Attitudes toward animals changed throughout history, although we primarily believed they were here for our usage, which has led to a great deal of regrettable mistreatment and exploitation of our fellow creatures. The idea that an animal is an individual, or a sanctioned being, was never universally popular. However, everyone who cares for a pet knows that each animal has its own personality. A dog is a dog, but all are different. The same for eagles or insects. Are there introverted sponges or extroverted ants? Is there a mean-spirited termite or a butterfly who is frightened of flying?

Without animals, there would be no human civilization. We would have been among the multitude of trial-and-error species that came and went—gone in a bleep of time—without them. They were our food and clothing. We imitated how they hunted; animals, birds, and even insects showed us where to collect fruits and grains and provided raw materials to make our shelters. Our first roads were their migratory paths; they were the engines that built cities. But who are they, these millions of creatures that live with us? Do they think the way we do? How do they feel? How is it that they live and die? Did two-headed beasts actually exist and what of the myriad species that were here and are now gone? What clues can we learn from the myths from which they sprang or of their fossilized bones?

We try to imagine how animals see the world, but even our pets are mysterious to us. However, understanding the way their eyes work or their sense of smell, for example, helps us to appreciate them even more and adds a measure of empathy, if nothing else. Appreciating the vastness of these individual lives, from the smallest microbe to the greatest whale, makes us more human. Shamans of old looked for the spirit of an animal, believing all creatures had special powers. Each animal was either an instructor or a link to an ancestor that would speak through it and reveal an unknown universal language. In this book, I hope to return to that momentary wonder we had as children. I remember when I first learned of a giraffe’s preposterously long neck, or heard the incredible roar of a lion, or observed the organized and ever busy trail of ants—I was amazed by the wonderful strangeness of things. I also look at the beasts we created with our imaginations and the ones long gone. How incredible to think of the very first birds that learned to fly, or what it was to exist as a 10-ton dinosaur. Mythical creatures that breathed fire or burned themselves to become immortal are intensely compelling. Did they truly live? In our need to understand, and with our creative resourcefulness, they did—and who really knows that they didn’t.

Science and technology have proved that what was once thought impossible can, in fact, become probable. Nothing is constant, as many things in science are discovered, refuted, and reevaluated again and again. Who knows what it is that makes us essentially human and at the same time so similar to animals. What separates us from creatures and beasts—real, mythical, and extinct—might be only the trace of a tail line left in the sand. As philosopher Herbert Spencer said, in a variation on a William Paley quotation, “There is a principle which is a bar against all information, which cannot fail to keep a man in everlasting ignorance—that principle is contempt prior to investigation.”