1936–1940

Gradually, John began to cultivate an identity as a quick wit. He honed his comic persona in the company of family and friends. If he said something funny enough at home, his mother would look up from her housework long enough to say, quite seriously, “Oh, John, you are such a card.”1 He was bored in school and irritated by chores at home, but he discovered there were funny ways to protest what he did not enjoy so that no one, least of all his father, who would have spanked him for it, could tell he might be complaining. He also continued to study music and painting, and privately read about new developments in the history of art. Although he had given up writing poetry, he could not rid himself completely of the idea that maybe someday, as unlikely as it seemed, he might become an artist.

In July 1939, John attended sleepaway camp for the first time. He did not want to go; he had successfully avoided being sent there a year earlier.2 Despite his efforts to resist, his family drove him to Camp Cory, a YMCA camp on Keuka Lake, near Rochester, and left him at the boys’ dorm for nearly two weeks, the longest period the eleven-year-old had been away from home. His parents felt that two weeks spent outdoors with other boys his own age would be good for him. He hated the place, particularly the daily schedule of recreation: sailing, canoeing, and making jewelry in the craft shop, which many boys called “The Crap Slop”—activities he took great pains to avoid.3 At the beginning of his second week, he wrote a letter to his grandparents (who had paid for the experience):

July 12 1939

Dear Grandpa and Nana: I am having a nice time at camp. I sleep in a top bunk from whense [sic] I am writing you. The food is very good more so than at home. To-morrow we are going on a canoe trip. The counselor and boys are nice. Much love to everybody.

John4

In its six laconic sentences, the missive was more deadpan and parodic than anything he had ever written before. Suddenly, he made some creative use of his misery. Even the inclusion (and misspelling) of the archaic “whence” suggested his arch approach to composing not just any letter home, but the most quintessentially dull letter from the most average camper of all time. He embellished the letter’s lack of detail, emphasizing its absence of substance by repeating even nondescript phrases, a technique that heightened the missive’s manufactured blandness. He also imaginatively rendered a first-rate mealtime to get a rise out of his audience.5 In fact, by the end of the session most campers were confined to the infirmary after rancid butterscotch pudding sickened nearly everyone, which confirmed what John had already strongly suspected about camp food.6

During the following fall, in eighth grade, he wrote another, even more substantial parody.7 He composed the “fake report” in his English course during an especially dull class period. When his kind and tedious teacher, Mr. Klossner, asked each student to write a true story and then read it to the class, John invented a fictional story in the form of a newspaper account:

[T]he school children in Mansfield [Ohio] were all very civic minded.… [T]here had been a lot of traffic accidents involving children and so they decided to form their own police force for pedestrians and helping people across the street and stopping cars and everything.

He had never been to Mansfield but had been hearing about the city for years, from his grandfather’s letters on Mansfield-Leland Hotel stationery and from his mother and grandmother, who “were always talking about how nice the tourist hotel was.” He simply wanted to be able to express his dissatisfaction—with his small-town American life and its inanities, sentimentalism, boring school assignments—without getting in trouble for his critical views. Throughout an otherwise fabricated account, John sprinkled bits of local lore he had picked up. As soon as he read his piece to the class, Mr. Klossner “became very excited” and went “running up to the front of the class and said, ‘Isn’t that fantastic! Listen kids, if kids can do that in Mansfield, Ohio, then they can do it in Sodus!’”8 John was shocked that his “fantastic” story seemed believable to his teacher and classmates.

He had recently performed in the school play, learning to sharpen his delivery to get bigger laughs. The seventh-graders put on Louise Saunders’s slight and witty one-act verse comedy, The Knave of Hearts, and despite John’s inexperience, Miss Florence Klumpp, a new teacher and the young director, assigned him the starring role of “the knave.”9 His mother helped him by sewing, at his request, a ridiculous red suit with an “eighteenth-century doublet,” through which to enhance the buffoonish nature of his character. He gleefully prepared his part by practicing exaggerated gestures and mispronunciations, behavior and speech that Miss Klumpp directed him to heighten even more (saying pomp-de-belly, for example, instead of pompdebile), in order to make his performance as funny as possible.10

After the success of this production, John started to write his own material. The first one-act play he wrote, which he entitled Ye Gods, was a religious parody. The title of the lost play suggests that it drew on his knowledge of Christian education and his enthusiasm for Greek mythology and other pagan myths. On June 6, 1937, he was confirmed in front of his entire family at St. John’s Church in Sodus, an event he viewed as a public occasion much more than a religious one. Afterward, Addie gave him an inscribed Bible to commemorate the event, and he read the book carefully and skeptically over the next few years.11 He described his work-in-progress in one of his first letters to Mary Wellington—“P.S. No. 3 I am writing a play called “Ye Gods.” Its [sic] a scream to say the least”—extolling its possibility as a witty vehicle for his friends to perform together over the summer in Pultneyville.12 Despite his initial enthusiasm, he never mentioned it again. As was the case with many other plays he would begin over the next few years, he probably did not finish writing it. Ideas took hold of him, and he worked intensely until he did not know how to develop them further.

He was constantly swept up by new ideas, especially during sixth grade, when an illness gave him time to read and learn whatever he wished. For most of sixth grade, from October 1937 to April 1938, John and Richard (who was in first grade) stayed home together with scarlet fever and then whooping cough.13 Although neither boy felt terribly ill, the doctor prescribed extensive bed rest. Staying inside to read and listen to the radio was what John already liked to do best anyway. For seven months, he easily avoided his three least favorite activities: chores, exercise, and outdoor recreation. He also had his own room once again, after his mother temporarily moved Richard down the hall, and he enjoyed his privacy. She placed the big family radio in the hallway between them for entertainment. The primary drama of the day involved arguments about which radio programs to play. Richard loved The Lone Ranger; John preferred soap operas such as Ma Perkins and Pepper Young’s Family, and liked the ads. One afternoon when his mother came to his bedroom to do her daily cleaning and disinfecting of the space, he made up a new joke, punning on a disinfectant and sung to a popular tune: “Lysol you last night and got that old feeling.” His mother looked up briefly from her work to laugh.14

The radio show that John could not bear to miss each day, however, was Vic and Sade, a fifteen-minute program written by Paul Rhymer that chronicled the average life of the Gook family. Mr. and Mrs. Victor Gook (Vic and Sade) and their son, Rush, live in a small, cozy house in a small town. A revolving cast of friends, including “Smelly Clark” and “Bluetooth Johnson”—names John loved—stop by to chat. Often the story begins with a simple family conversation, for example:

RUSH:… Nicer Scott claims he can unfry an egg.

VIC: I bet he can’t.

RUSH: Ain’t it ridiculous a guy claimin’ junk like that?

VIC: How does he go about unfryin’ eggs?15

The Gook family would find these sorts of nothings to talk and squabble about, seemingly desultory conversations revolving around bland subjects such as weather or housekeeping that John thought were “brilliant.”16 Listening every day for months, he memorized snippets of the show, absorbing its combination of slowly unfolding conversational rhythms, its dry sense of humor, and its piercing observations about family, education, and culture in American small-town life, delivered with a sweet understatement that made their sardonic intent easy to miss.

Shortly after the boys finally returned to school for the end of the year, Helen celebrated their good health by taking them to see Errol Flynn’s new Technicolor film, The Adventures of Robin Hood, in nearby Newark. They thought Flynn was just the right mix of irreverent and heroic, an excellent Robin Hood. John began addressing Richard as Sir Richardson. As soon as they arrived in Pultneyville for the summer, he came up with the idea to open a “Knight Club.” He invited all the children spending the summer in the village to join the club, where they discussed their exploits and addressed each other as “Sir” this and “Sir” that. Among the new group of children were several whom John especially liked: Eleanor “Barney” Little, a dark-haired, serious girl and a voracious reader, and her cute, vivacious younger sister Joan (Jo). Carol Rupert, the daughter of Ottilie (Teal) Graeper Rupert, Helen Ashbery’s best friend from college, stayed in the house next door to the Lawrences’. Along with her younger brother, Pede, she lived all summer at the home of her maiden aunts, three beloved and intelligent sisters (Emma; Carolyn, known as Connie; and Olga) whom everyone in the village called the Graeper girls. Carol had a “deep timbre voice” that made her sound mature, but she was a year and a half younger than John and treated him as an older brother.17 Her cousin Billy Graeper, a year older than John, stayed in a rental house a few doors down with his parents and also began to play with the group.

Richard, Carol, and John on the swings in Pultneyville, 1936

John and Mary Wellington led the Knight Club together. In the film, Olivia de Havilland played Maid Marian, but none of the children cared for the role of the damsel in distress. Seamlessly blending the legends of Robin Hood and King Arthur, John spoke to everyone in an imaginative version of medieval English, and everyone took turns playing a knight of the forest, an outlaw, King Arthur, or Robin Hood. The area of willow trees became an amalgam of Sherwood and Windsor Forests, described with a smattering of history and myth added and invented as needed. John advised each of his friends to choose a tree (and surrounding grounds) that would serve as his or her castle.18 There were occasional insurrections, such as when Richard and Carol pulled away the ladder that John was using to survey the scene from a barn roof.19

The following summer, the “knights” picked up right where they left off, and their histories grew even more elaborate, expansive, and wittier. The children spent more time in their imaginary “kingdoms, empires, domains, dukedoms, and marquisdoms … and—oh yes! Duchessdoms,” and talked for hours about what to name their castles and realms.20 Years later, Ashbery wrote several poems that directly alluded to the Robin Hood story, his connection forged in earnest through his frolicking childhood games. In “Meditations of a Parrot” (Some Trees, 1956), the parrot repeats “Robin Hood! Robin Hood!” while looking at the sea. Twenty years later, the title “Robin Hood’s Barn” (Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, 1975) invoked both the idiom “to take the long way around” and his childhood memory, as the speaker reflects on an experience of growing up, as “… your young years become a kind of clay / Out of which the older, more rounded and also brusquer / Retort is fashioned.”

This period in Pultneyville was a particularly rich source of “clay.” He memorialized his affection for Barney Little, for instance, with a reference to the race car driver Barney Oldfield in A Nest of Ninnies (1969), the man after whom she earned her nickname to mark her very speedy birth. Many of Ashbery’s later poems also invoked the transient feeling of summer, a mood that John identified early on as school and farm life loomed ever closer in August: “Alas, the summer’s energy wanes quickly, / A moment and it is gone” or, even more wistfully, “a hint / of fall in the air, soggy and bored.”21 The happiness John felt in Pultneyville served as a kind of armor to help him withstand any unhappiness he felt during the rest of the year, and it protected him from other sorts of pain as well. In Flow Chart (1991), Ashbery’s sophisticated reflections on the past briefly slide, for a moment, into the language of childhood retorts: “I’m rubber / and you’re glue, whatever you say bounces off me and sticks to you,” since the “words have, as they / always do, come full circle.”22 In the later “Episode,” he describes how dramatically social culture shifted from the beginning to the end of the 1930s, crucial changes that, as a young boy, he noticed from the sidelines without understanding what such shifts in taste might mean:

In 1935

the skirts were long and flared slightly,

suitably. Hats shaded part of the face.

Lipstick was fudgy and encouraging. There was

music in the names of the years. 1937

was welcoming too, though one bit one’s lip

preparing for the pain that was sure to come.23

In the mid-thirties women’s “lipstick was fudgy and encouraging” and “music” could still be heard and felt. By 1937, a feeling of optimism was giving way to something darker, but John did not connect Lillian Holling’s often repeated remark around Pultneyville that “what can’t be cured must be endured,” or his mother’s “life is a funny business,” with worrisome radio reports about Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler’s increasing power, or the likelihood of another war.24 These world events did not interrupt his imaginative playtime in Pultneyville’s lake and trees, but shadowed it, forming pieces of the “clay” he would dig up and sift through later.

Ever since his failed attempt to write a second poem after “The Battle,” John had pushed aside thoughts about writing poetry. In late December 1936, however, he picked up Life, the new magazine his grandfather subscribed to, and read a feature article on an art exhibition, “Fantastic Art: Dadaism and Surrealism,” opening at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and he was swept up again in thoughts of art and artists. He had never heard the term surrealism, but the magazine’s definition of surrealist art as “no stranger than a person’s dream,” was both completely understandable and very appealing to him.25 The article included photographs of objects from the exhibition: Meret Oppenheim’s now famous fur-lined teacup; paintings by René Magritte, Salvador Dalí, Giorgio de Chirico, and Pablo Picasso that used images of clocks, trees, houses, and chairs, but their shapes and colors altered in such a way that they became slightly stranger and more menacing in the process. Here were examples of ordinary objects that John saw and used every day presented as art, and he found that in their transformation, they became more compelling. To see objects from his dull world tweaked slightly, just as a dream might do, and in that process of transformation becoming something new, vivid and exciting, thrilled him. Seeing the strangely beautiful examples of surrealist art consciously rekindled his former desires to become an artist.

John wished to go see the exhibition in New York City, but since that was impossible, he asked his grandfather to take him to the Rochester Central Library downtown, which was a beautiful “art-deco gem” he liked to visit, to learn more about surrealism.26 He found Julien Levy’s new volume, Surrealism (1936), on the shelves and sat down at a table. The text, a combination of history, analysis, and artistic examples of the surrealist movement, was both dense and playful, certainly not written for a nine-year-old boy, even a precocious one. Yet the young Ashbery at once responded to the rebellious, critical, energetic spirit of the artistic movement.

As he flipped through the images of surrealist art at the end of the book, he felt a jolt at the sight of Joseph Cornell’s Soap Bubble Set (1936), which resembled a child’s homemade diorama, containing bits of a clay pipe used to make soap bubbles with “marbles, and toy birds,” but put together in such a way that their very ordinariness seemed “dazzling.”27 John felt “astonished” to see these ordinary toys and bits of unimportant things he had enjoyed as a young child transformed by Cornell into something so strange, extraordinary, and beautiful.28 Looking at the photograph of Cornell’s box triggered a nascent thought that other things from his own “dim, dopey” life might also have the potential to become art.29

He began to learn much more about art. After Sodus schools dropped their art program in 1938, his grandparents arranged for both John and Richard to begin Miss Rebecca Cook’s painting class every Friday afternoon at the Memorial Art Gallery on University Avenue in Rochester. The weekly trips to Rochester alone gave him something to look forward to, but he also felt stirred by the stunning museum, and by the chaos of the basement art rooms, with their “smell of paint … the floor wax, and the mess.”30 For his mother’s forty-sixth birthday, on August 15, 1939, and to commemorate the end of his first year of study, John presented her with “a copy of a crayon drawing of Anne Cresacre by Hans Holbein [the Younger].” Holbein was famous for his portraits, and his intimate, psychologically probing, and very mysterious portrait of Anne Cresacre, completed in 1527, was considered one of his best.31 It was also the painting John knew most intimately, for a print hung in the Ashbery living room, a wedding gift to his parents and one of the only pieces of art in the farmhouse. In his rendering, John carefully and successfully captured Anne Cresacre’s gaze, the very aspect of Holbein’s portrait that made it so mesmerizing. His father helped him fit his finished work with a frame.

John painted this copy of Hans Holbein the Younger’s Anne Cresacre for his mother.

John was in the midst of a period of remarkable physical and personal growth. He had become exceptionally gaunt and tall. A photograph taken in August 1939 showed him towering over Richard and their two-year-old cousin Larry Taft. He was also (as were his friends) beginning to experiment sexually in ways that were changing his feelings about others and himself. On one evening over the summer, he kissed Mary Wellington after walking her home, but her surprise seemed to him a brusque rebuff, and it never happened again.32 On another afternoon, at a picnic, he shared a flirtatious kiss with Jinny Gilbert, the daughter of one of Helen’s college friends, who promptly told Carol Rupert all about it.33 Carol’s cousin Billy Graeper, who was visiting Pultneyville for several weeks of the summer as usual, slept over in John’s room on several nights, and they sometimes kissed and touched, though they never mentioned what happened between them, either to each other or to anybody else. John could recall feeling attracted to boys as far back as kindergarten, but he was conscious of this strong feeling now in ways he had never been before. He kept this knowledge secret, for he “didn’t know there was such a thing as homosexuality” and worried he might be “the only one so afflicted.”34

John and Richard had enjoyed the summer so much that by January 1940, they were already beginning to plot activities for the next one. Their idea, which John shared in a letter to Mary Wellington, was to mount a full performance of The Knave of Hearts for the village. He would star as the knave, since he already had the costume and knew the part. Mary would play Violetta, the other lead. He assigned Richard the part of a herald and doled out other roles to all the children. He planned to ask Pat Brownbridge to direct.35 Pat was a stout, swarthy, middle-aged man who lived in Pultneyville with Henry Lawrence’s cousins Lillian and Paul Holling as their “manservant,” and went to every family function with them. Everyone accepted him as the elderly Paul and Lillian Holling’s butler, though John eventually understood, about a decade later, that Paul and Pat were, in fact, lovers.36 He was a jovial extrovert who often mentioned that he had done some theatrical training early in his life in Ireland, and John thought he might be interested in helping to put on the play.

Larry Taft on Helen’s lap, John (standing), Richard (in front), Henry Lawrence, Addie (standing), and Janet Taft (holding Sheila), 1939

John, Larry Taft, and Richard, August 1939

John and Mary Wellington at the Pultneyville Firemen’s Fair photo booth, summer 1939

Chet and Richard, Ottilie (Teal) and Carol Rupert, and Henry Lawrence in Pultneyville, 1939

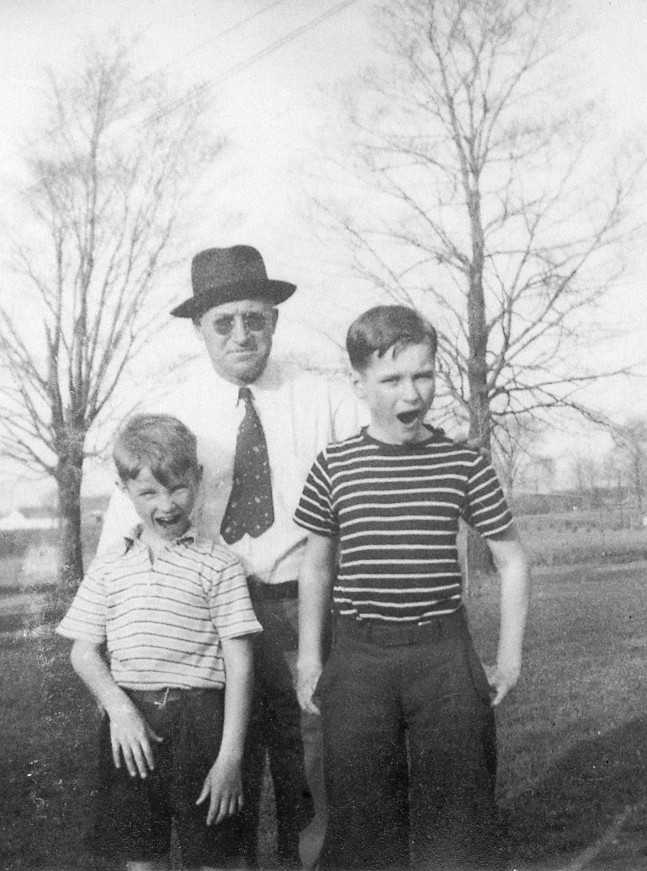

Richard and John “clowning” with Chet, 1939

Preparations for the summer accelerated even as John began to mention to Mary in passing that Richard was home sick. In February, he wrote that Richard had been diagnosed with “rheumatic fever,”and John had stayed over at Carol’s in Rochester for three days to see the “swell” Pinocchio, not realizing that the two events were connected. His parents had sent him to the Ruperts because Richard’s illness, which began around Washington’s Birthday and was initially diagnosed as grippe, had continued to worsen.37 Helen and Chet were trying to determine what was wrong with him, but the doctors’ diagnoses kept changing, and no one wanted John to worry unnecessarily. John stayed very busy, starting a new stamp collection, attending art classes at the Memorial Art Gallery and writing long, amusing letters to Mary about her pet duck, which she had originally believed was male, rechristening it “Lady Jamaica Wallingford Featherskirts Daffodilia Wellington Duck” (“Daffy” for short).38

Paul Holling (son of Mary Sheffield and Armine Andrew Holling), Henry Lawrence’s first cousin, at age twelve in 1884

As John focused on casting the play, his parents grew increasingly worried about Richard, but they shielded John from knowing anything more. On March 8, Chet Ashbery bought Richard a two-wheel bicycle as a present for his upcoming ninth birthday, on March 12. Just before his birthday, Richard’s health deteriorated and he was admitted to Strong Memorial Hospital for more tests. After three weeks in the hospital with a series of shifting diagnoses, doctors were still uncertain but suggested probable leukemia, at that time a fatal disease for a child. Out of a combination of their feelings of protectiveness and uncertainty, John’s parents continued to keep him quite ignorant of what they feared was the severity of his brother’s illness. He visited Richard in the hospital only once, finding him more sleepy and confused than ill.

John attended school and continued to do well in his classes. He and Richard had both stayed home before with childhood diseases. John supposed, and no one corrected him, that Richard had the same sort of illness. Even the fact that Richard was staying in Strong Memorial Hospital was not necessarily alarming, since John had also stayed there once, to have his tonsils removed, and Addie and Henry went frequently for appointments.

By early April, however, doctors had diagnosed Richard conclusively as suffering from “acute lymphatic leukemia” with “secondary anemia.”39 John’s parents informed him of the name of the disease without explaining its prognosis. Richard’s health was deteriorating very rapidly, and no medicine yet existed to stop it or slow it down, as there would be less than a decade later. Richard returned home from the hospital to Sodus and seemed to improve with regular blood transfusions, but there was nothing else doctors knew to do to save him. Many of Chet’s and Helen’s friends donated blood.40 John knew very little of what was happening because his parents had sent him to stay with his grandparents in Pultneyville. He was told only that Richard was home again from the hospital, and he assumed that his brother was improving.

From Pultneyville, John could properly prepare for the summer, and he wrote Mary about his solo explorations of their willow tree kingdom, which had been completely flooded in early spring rains. In passing, he mentioned that Richard had “Lukemia” [sic], but the letter contained no other discussion of what that meant. His parents were not telling him anything, and indeed, they were probably frightened and confused themselves, for not much was understood yet about childhood leukemia. The letter to Mary contained a detailed account of the state of their respective castles and a playful plea not to “get all quacked up”—not to worry about the flooding—“cause the same thing happens almost every year, and next summer you won’t know the difference.” It was a statement likely as much for himself to keep at bay his general anxieties about Richard’s strangely lengthy absence, of which there was still no word, as it was to her about the imminent destruction of their kingdom.41

By the end of April, John was back in Sodus and Richard had moved to Pultneyville for more transfusions. Carol, too, was sick, with scarlet fever, and her house had been quarantined; John believed both would recover. His immediate concern was to figure out how he and Mary could best protect their kingdom from the danger of potential invaders once summer began:

We shall take our cups, saucers, winebottles, and even wrigley vines. We shall have a hidden garrison where everyone (of us) will run for when the alarm sounds. It shall be camouflaged, of blackberry bushes, grass, and vines. If the marauders get to [sic] daring, we shall bombard them with deadly mudballs. It shall be a secret kingdom, with a secret entrance. No one but we four or perhaps our parents shall no [sic] about it.42

John created “a book of magic recipes” using ingredients they could procure by the creek. They would be able to write secret notes to each other using lemon juice and heat, a “wonderfully spooky” trick he had recently learned from The Book of Knowledge. He was looking forward to lemonade and hot dogs at Pultneyville Firemen’s Field Day, swimming in the lake, and especially their “secret kingdom.” With such extensive forethought, John presumed this summer was going to be their best ever.

He sent no more letters that summer. In early June, Richard worsened, and Chet Ashbery bought him a “wheel about chair,” as he was too weak to walk.43 While John finished school in Sodus, Richard received regular transfusions from blood donated by friends in Pultneyville. These transfusions seemed to help the secondary anemia, and reports trickled in that Richard’s condition was improving. John finished eighth grade by winning the district spelling bee, the only student with a perfect score.44 He then won the county spelling bee in Palmyra, the first Soduskan to do so. This county victory meant that the bee would be held in Sodus for the first time the following year. At Class Day, John received $2.50 as the student with the highest average in school and a special award for winning the county bee.45

When school ended, Helen sent him to stay with his “aunt” Aurelia and “uncle” Sandy at their comfortable home in Greece, New York, just outside Rochester. Aurelia Hillman Sanders had been one of Helen Lawrence’s dearest friends in her sorority at the University of Rochester, and John was fond of their adopted son, Dick, who was about the same age. John always looked forward to visiting them at their pretty home. He was told that Richard, who had always loved the Fourth of July, planned to watch the fireworks, encouraging news that suggested he was becoming healthier. No one told him what they must have known by this point: that Richard was dying.

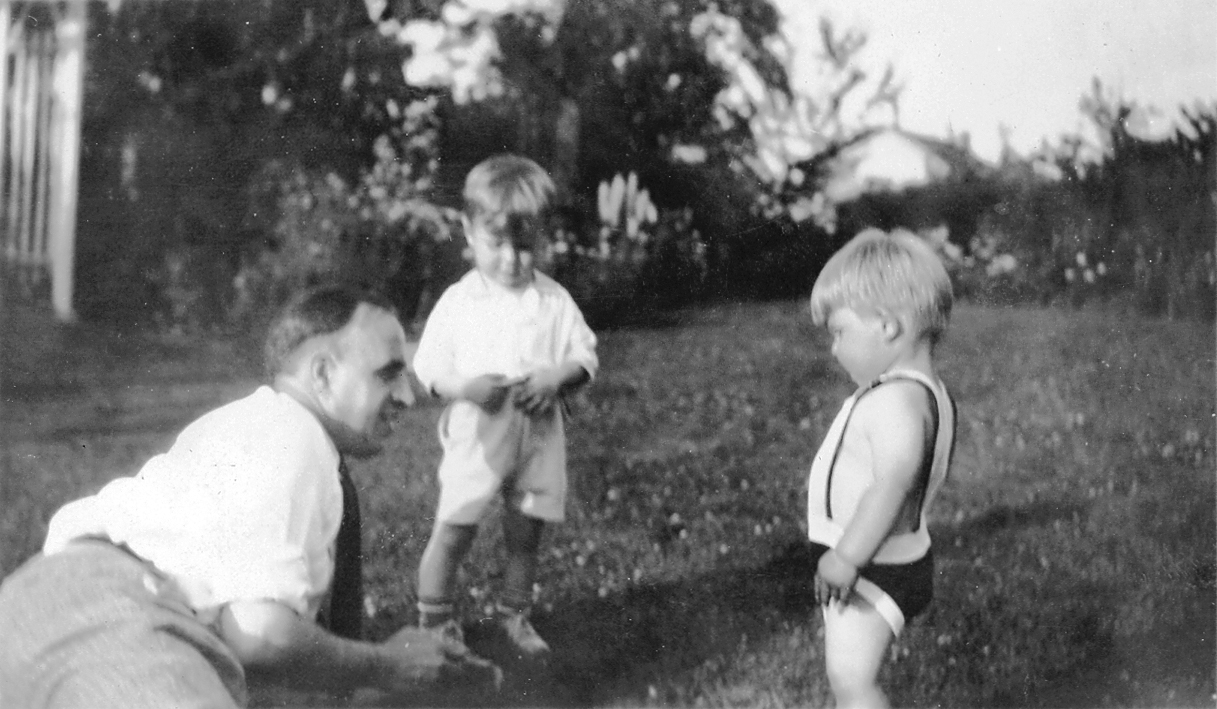

“Uncle” Sandy (George Sanders) with John Ashbery and Dick Sanders, about 1930

A few days before July 4, Carol, who had finally fully recovered from scarlet fever, went to stay with her aunts in Pultneyville. Richard was staying in a bed in the living room at the Lawrences’ house, next door, and she went over to visit him. He lay in bed and looked so pale and weak, so extremely ill, that she felt incredibly scared for him.46 She had not understood until that moment how seriously ill he really was. A day or two later, his doctors said that there was nothing more they could do. Richard was brought home to Sodus on July 3. He seemed to rally the next day and recognize the holiday, but the following morning he was not doing well. Chet and Helen sent for John. It was Friday morning, July 5, and the fastest way to return home was by car. Aurelia drove John to Rochester. Carol’s aunt Connie met him there and drove him back to Pultneyville so that his grandfather could take him home to Sodus to see Richard.

When John reached Pultneyville, just after three in the afternoon, his grandfather told him his parents had phoned; Richard had just died. John was confused and shocked. He had no idea what his grandfather meant. He still had not grasped that death was even a possibility for his brother. He walked into the backyard and saw Carol’s little brother, Pede, and told him that Richard was dead. Pede was so upset that he ran back into his house. Carol heard the noise of the banging door, looked out her bedroom window, and saw John in his shorts and shirt, knocking the rolled-up comic book he had brought for Richard against one hand and wandering around alone in Henry Lawrence’s vegetable garden, waiting for his grandfather to drive him back to Sodus.47

* * *

The funeral for Richard was on Monday, July 8, 1940, at two thirty in the afternoon at Ashbery Farm. Reverend John Williamson arrived from St. John’s Church to conduct the service. “There were banks of Easter lilies,” sent by local families, the smell of which overpowered all others and lingered for days.48 John’s parents arranged for Carol and her aunt Olga to take him on a picnic in Pultneyville during the service, but just as they were leaving the house with their picnic basket, John saw the funeral procession, with the hearse carrying Richard’s casket, as it drove down Washington Street toward the Lakeview Cemetery. The Lawrence family ancestors, including all the Throops and Hollings families and their direct descendants, were buried there, on plots of land that bordered Lake Ontario and offered to the grieving the most magnificent views of the lake imaginable. As John recognized the procession passing the house, Olga hurried him back inside under the pretext that they had forgotten some essential item for their picnic, and he pretended not to have seen anything.

Later that night, John returned home to Sodus. Over the next few days and weeks, the family did not say much to one another, but they each made some small adjustments. Chet began reading the Bible every night, staying up late and studying the Christian Scientist Mary Baker Eddy’s testimonials on the power of faith. He framed a photo taken the previous fall of Richard throwing a football, his young son’s athleticism and charm fully displayed. Chet had finally taken the old roll of film to be developed on July 1, 1940. Helen, Chet, and Elizabeth worked on the farm, for it was nearly cherry season and there was a lot to do. Richard’s twin bed was removed from John’s bedroom.49

Each family member kept to himself. John roamed about, and one afternoon, in the back of a closet, he discovered piles of unopened gifts Richard had received while he was ill. He left most of them alone, but he took a few books, including Marie-Catherine D’Aulnoy’s translation of The White Cat, and Other Old French Fairy Tales, which his parents’ friends had given to Richard not knowing he was too ill to read it.50 A half century later, Ashbery would translate the bittersweet tale of “The White Cat” from French.51 John’s parents sent him to visit his aunt Janet, uncle Tom, and three-year-old cousin Larry for a few days in their new house in Elmira, New York. John sent his parents a postcard, noting that he was having a nice time and had purchased some new “songlasses” [sic]. When he returned home, his parents remarked on his poor spelling, which he found insulting.52 Only much later did it occur to him that they were suggesting he had been thinking of Richard.

Richard playing football, fall 1939

The Rupert family arranged to take John and his parents on a trip at the end of July. Although they grieved for Richard, they worried even more about the impact of his death on the rest of the family. Carol’s father, Philip, who had been Chet’s best friend in the 1920s and who had been responsible for introducing him to Helen, drove the car. Ottilie “Teal” Rupert was still Helen’s closest friend more than twenty years after graduating from college. They traveled first to visit Teal’s sister, Alma Dandy, in Ogdensburg, two hundred miles northeast.53 Alma and her husband, Howard, were committed Christian Scientists, and they talked with Chet about faith, conversations that John overheard and found strange and upsetting. The next day, they continued on to visit Paula Grant, another of Teal’s sisters, who lived one hundred miles farther east, in Plattsburgh, on Lake Champlain. A photographer snapped a stark picture of the group in matching touristy hats and strained smiles on a boat trip down the St. Lawrence River. After Plattsburgh, the group drove to Blue Mountain Lake, which was meant to be the highlight of the trip.

The two families arrived in Blue Mountain, checked into their hotel, and walked down to the lake. John had stayed there overnight once two years earlier, on the way back from a brief genealogy mission to Vermont with his mother and grandparents. At that time, everyone had felt lighthearted. His mother, especially pleased with a tourist hotel they stopped in near Ticonderoga, had declared its floor “so clean you could eat off of it,” an expression John had never heard before and which delighted him.54 In his grief, John found that everything that had happened before, especially those fleeting, pleasant memories, had taken on a different valence and color, as though the memory itself had changed. To add to his confusion, it was his thirteenth birthday. Much later, in Flow Chart (1991), Ashbery could describe a version of how it felt to be “handed a skull / as a birthday present”:

Early on

was a time of seeming: golden eggs that hatched

into regrets, a snowflake whose kiss burned like an enchanter’s

poison; yet it all seemed good in the growing dawn.

The breeze that always nurtures us (no matter how dry,

how filled with complaints about time and the weather the air)

pointed out a way that diverged from the true way without negating it,

to arrive at the same result by different spells,

so that no one was wiser for knowing the way we had grown,

almost unconsciously, into a cube of grace that was to be

a permanent shelter. Let the book end there, some few

said, but that was of course impossible; the growth must persist

into areas darkened and dangerous, undermined

by the curse of that death breeze, until one is handed a skull

as a birthday present.55

Philip and Carol Rupert with Helen, John, and Chet on the St. Lawrence River, July 1940

The Rupert and Ashbery families on the top of Blue Mountain, July 1940

The image Ashbery paints in his poem brings to mind Frans Hals’s painting Boy with Skull: the open curiosity and energy of a young boy “undermined / by the curse of that death breeze” that thrust a skull into his hands one afternoon and required him to carry it up a mountain. A group photograph at the summit documented the grief-stricken families. That night, they went to eat supper at a diner in the village. The place had a jukebox, and Carol asked John to dance, to help make the dinner feel more festive. When they stood up, John spotted a very elderly couple sitting alone in a booth. They were storekeepers he had seen earlier in town. He thought they looked terribly frail and tragic, and he started sobbing. His family comforted him, assuming that his grief was for his brother. He kept trying to explain to them that they were wrong, that he felt sorry for the elderly couple at the other table.56

John and Helen (and Sheila), August 1940. Photograph taken by Chet Ashbery.

The summer had never happened, yet it had also felt so long already, and it was only the beginning of August. Back in Pultneyville, Carol’s mother suggested that the children put on a play. It was an activity that she thought might cheerfully occupy John. They had already started work on preparing The Knave of Hearts, but no one wanted to perform it anymore, perhaps because it had so many parts, one of which had been assigned to Richard. Instead, Carol’s mother suggested they learn The Princess and the Robber Chief, a short, four-character play loosely based on the King Arthur legend that she had seen in a book during college. She told John about it, and in a few days he had written it out in his own hand. Carol was to play the Princess; John the King; Mary would be the Robber Chief. The children found old costumes, sold tickets, and performed in the barn behind Carol’s house. The play concerns a melodramatic love story between the Princess and the Robber Chief, for which the King finally sacrifices himself. His last speech:

Soon your wicked blood will flow

And the whole wide world shall know

That I, though, old and weak and sad

Yet a lion’s courage have.57

The Robber Chief then stabs the King to death, and afterward explains to the Princess why he must run away and hide. She is so moved by his words that they fall instantly in love. The play ends with the Princess’s surprisingly optimistic statement: “Love doth conquer all.”

The performance was a great success. Someone took a photograph of the actors in their costumes, to mark the occasion. Mary stands in her Robber Chief’s attire hugging Carol, the Princess. John, kingly in robes and a crown, surveys the scene wisely. In the background: a lovely summer’s day in Pultneyville with a bevy of relatives and other elderly neighbors milling about. The production had done what Teal intended. John did not know at the time that the suggestion to put on a play was meant to distract him from his grief, but it had temporarily worked. He had focused his attention on wittily adapting four pages of rhyming verse, and this work brought friends and a community together and entertained them. This experience demonstrated, in a way so natural that it remained an unarticulated insight for many years, a communal value to the work of writing. The performance of the play remained the highlight of the summer for audience and performers alike, referred to as a special event by those involved, ultimately separated in their minds from the tragedy that preceded it.58

Carol, Mary, John, and Carol’s brother Pede after the performance of The Princess and the Robber Chief in Pultneyville

In September, after John’s first week of high school, his parents took him on another short trip to Blue Mountain Lake with the Ruperts. John and Carol answered every question the adults asked them with “I durnt want to,” a phrase they thought fantastically funny.59 The trip was less sharply painful than the one of six weeks before, yet John always associated Blue Mountain with the shock of his brother’s death and his family’s pain and grief. Later the word blue invoked for him, among its many other associations, those trips, too, and the loss of his brother: “the blue snow”; the “steep blue sides of the crater”; the “blue cornflakes in a white bowl”; and “the extra worry began it—on the / Blue blue mountain.”60

In the weeks that followed, John pretended not to see his parents grieve. Chet was very quiet, turned inward; he had stopped drinking, and tried to find comfort by studying the lessons of Christian Science. He had already developed and framed the photograph of Richard throwing a football, and now he placed the picture, which was exactly the image of what John believed Chet most desired in a son, in the living room, on a side table just beside his reading chair.61 Every night, Chet sat down next to it and read Mary Baker Eddy’s testimonials of the miraculous recoveries of believers, stories he had not read early enough to save Richard.62 Chet’s sense of loss was irreparable, and it magnified the sense of isolation he had felt due to earlier losses, beginning with his father’s death in 1927 and compounded by his older brother Wallace’s sudden death from a heart attack the previous year. John felt guilty that he, the less athletic, less “normal,” less good son, had survived.63 Both John and Chet felt a powerful sense of guilt after Richard’s death, but they were unable to share it, retreating into their private thoughts in different corners of the house.

Without directly mentioning any of the details of that time in his life, John offered an image of his feelings at the very end of “Definition of Blue.” The poem offers an intensely personal description of a process of growing up, of coming to grips with one’s survival, one’s disappointments and feelings of guilt:

And yet it results in a downward motion, or rather a floating one

In which the blue surroundings drift slowly up and past you

To realize themselves some day, while you, in this nether world that could not be better

Waken each morning to the exact value of what you did and said, which remains.64

What “remained” for John and his parents was a stunned feeling, as though they had been knocked to the ground by a giant wave. They were reeling from the aftereffects of a storm so fierce and fast in its destructiveness that it had changed the entire landscape of their family. In “A Wave,” Ashbery continues the thought he begins in “Definition of Blue” to a more mature emotional reflection: “What is restored / Becomes stronger than the loss as it is remembered; / Is a new, separate life of its own. A new color. Seriously blue.”65 In this later poem, the difficulty of surviving and recovering from loss lessens over time, and eventually the blue hue one once knew is more than “restored,” becoming “stronger,” a “new” deeper, warmer, “seriously blue” color.

Shortly after returning to Sodus, Helen and Chet drove John to the New York State Fair in Syracuse to compete in the state spelling bee. He had been invited as a result of winning the county bee in June, an event that felt as if it had taken place in a different lifetime. For a few days at the end of September, John lived in a dorm on the grounds and was able to go on rides and enjoy the fair with other county winners from New York. There was a lot of activity, things to see and do, and the anonymity of being among crowds of other schoolchildren provided an unexpected reprieve from the intensity of the summer. The bee began, and John spelled D-E-S-P-A. He knew immediately he had made a mistake. He corrected himself, but it was already too late. He was out on D-E-S-P-E-R-A-T-E-L-Y, and his parents drove him home.66