The craterscape of the Western Front left an indelible impression on the young officers who survived it. Never again, they vowed, would they send so many men to their deaths so pointlessly. Two schools of thought emerged from this ordeal. Some believed airpower alone could end the next war quickly. Others believed tanks and armored vehicles could restore mobility to the battlefield and deliver the war-winning blows with speed and movement.

There my adventurous ardor experienced a sobering shock. A fair-haired Scottish private was lying at the side of the trench in a pool of his own blood. His face was grey and serene, and his eyes stared emptily at the sky. A few yards further on the body of a German officer lay crumpled up and still . . . machine guns tapped, spiteful and spasmodic. High up in the fresh blue sky an aeroplane droned and glinted. I thought what a queer state of things it all was. . . .

—Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, Siegfried Sassoon

THE GREAT WAR CAME UPON EUROPE in the summer of 1914, sparked by an assassin’s bullet and fueled by diplomatic miscalculations. Spurred by patriotic fever and images of glory and heroism in battle, legions of young men kissed their loved ones good-bye, stepped aboard troop trains across the Continent, and found themselves thrown into a new form of warfare nobody—from general to private—had ever envisioned.

They marched into battle in Napoleonic ranks. Instead of muskets, they faced Maxim machine guns and modern artillery. Garish uniforms, fit for striking impressions during the Bastille Day parades colored the French rank and file. The Zouaves wore blue and bright red pantaloons. Against the summer’s earth, they made exceptional targets for German gunners, and they died in heaps.

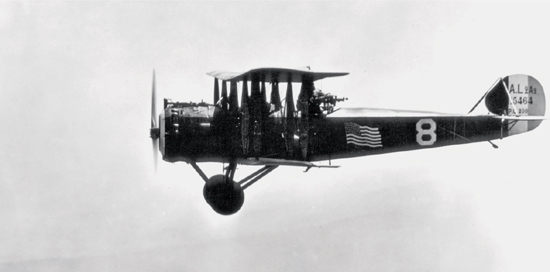

During the Great War, airpower served an important supporting function on the Western Front. Reconnaissance, observation, and spotting for artillery units were the aircraft’s most important duties. Here, an American 1st Aero Squadron Salmson recon aircraft soars above the front on a mission in 1918.

The concept of strategic bombing emerged from the traumatic experience of World War I’s trench fighting. The machine gun, combined with long-range artillery, produced such appalling casualties that offensive operations could be conducted only at the expense of thousands of young lives for every mile of ground taken. When the Armistice was signed in 1918, the surviving professional officers took stock of what they’d just been through and sought ways to ensure such positional warfare would never happen again.

In the first three weeks of fighting on the Western Front, five hundred thousand men became casualties. Before the year was out, the French Army alone had suffered almost a million losses.

The war devolved into positional fighting where a few hundred yards of ground would be bought with the blood of thousands of young men. Through 1915, the loss rates only grew worse. Then came Verdun in February 1916, and the French Army all but succumbed to the flames of that crucible. Before the year was out, Verdun had claimed almost a million more men.

Charles DeGaulle (left) was one of the armor advocates in the French Army.

In June, the reconstituted British Army launched its offensive along the Somme River. After a week long artillery bombardment, the British infantry was expected to simply walk over whatever German resistance was left. Instead, as the men clambered out of their trenches and marched in orderly ranks through no man’s land, they faced a hurricane of shrapnel and machine gun fire. By dusk, nineteen thousand British soldiers lay dead, some still lying in their parade ground ranks on the shell-savaged battlefield. Another forty thousand wounded overburdened the already inadequate medical evacuation pipeline, and their misery as they lay untended for hours or even days seems unimaginable now in a time when removing a casualty from the field takes a mere matter of minutes.

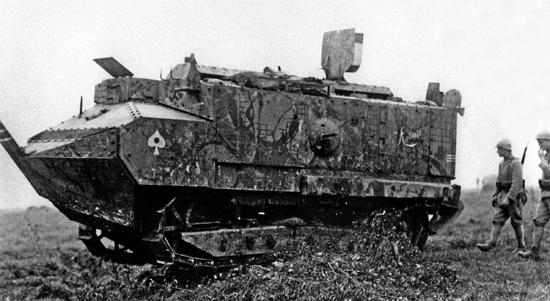

After the first British experiments with tanks on the battlefield, the French developed their own armored vehicles. Such first steps would give rise to the whole concept of combined arms—the integration of armor, infantry, and artillery into one powerful team on the battlefield. Colonel William Mitchell was the first—and, in the inter-war era, the only—airpower advocate who took the principle of combined arms operations and applied it to aviation. His tactical manual, written in the 1920s, was years ahead of its time as a result.

The pointless killing over ruined ground continued. The French Army nearly collapsed in mutiny. Units refused to charge headlong into German machine guns. Some bleated like sheep in their trenches when their officers ordered them to attack. Russia collapsed in revolution later in the year, and the Allied cause looked almost hopeless.

Most postwar officers, especially from the older Victorian generation, did not see much potential in airpower. They saw fragile, fabric-covered aircraft like these German Fokker Dr. I fighters and focused on their limited range, armament, and combat payload. These early aircraft did not have the capability to win wars, but the reality of the day blinded many to the potential that lay in the future.

The Americans arrived in the nick of time. The French and British armies, scarred by four years of trench warfare, had not the heart to carry the day any longer. The Americans, unknowing and naïve, stormed into battle with the same élan seen in 1914. In a matter of weeks, 250,000 U.S. soldiers and marines fell during the summer and fall of 1918. In the end, the Americans gave the Allies the spirit and numbers to at last defeat the German army on the Western Front.

When the war finally ended in the famous railroad car at Compiègne, Europe’s era of global dominance ended with it. Thirty million lives had been destroyed—eight million dead—in what became the bloodiest conflict in human history. The French mobilized 8.4 million men during the war; 5.7 million became casualties. Ninety percent of France’s eighteen-to twenty-four-year-olds died or were maimed defending the trenches of the Western Front.

A generation had been all but wiped out. Aside from the United States, the warring nations lay in economic and social ruin. Entire villages in Britain, France, and Germany had been picked clean of its healthy sons. Now in the aftermath, only the elderly, infirm, or adolescent remained to move forward.

In the wake of the war, those junior officers who survived recognized the complete failure of the upper echelons of their chains of command, most of whom seemed unable to adapt to the convergence of new technology and dated tactics that took place on the Western Front. Some young turks, such as J. F. C. Fuller, D. H. Liddell-Hart, George Patton, and Charles DeGaulle, advocated the use of armor to restore mobility to the battlefield. They clashed with the old-school infantry and artillery officers who seemed incapable of understanding how squandering the youth of their nation in pointless frontal assaults had crippled their societies.

Then there were men of extraordinary vision who embraced the airpower cause with almost zealot-like devotion. The most influential was Italy’s rebellious Guilio Douhet. He believed airpower, if used to destroy an enemy nation’s civilian morale through terror bombing, could bring a quick end to future wars.

The 1920s saw the first steps toward creating a bomber force capable of realizing Douhet’s bloody vision. Here, American MB-2 bombers pass over New York. From these dope-and-fabric-covered fragile craft would spring the deadly effective weapons of the following decade.

Other military rebels rose to prominence in the early 1920s. These renegades believed technology had made armies all but obsolete, and that the next war would be won not by rifle and bayonet, but by aircraft.

Enter the airpower zealots. One of the first of these was the Italian Giulio Douhet. In 1911, during the Italo-Turkish War, he glimpsed the potential of the aircraft as an offensive weapon of war. He commanded an air battalion in North Africa and during his stint in the desert penned one of the very first air battle manuals ever written.

During the Great War, Douhet relentlessly advocated for a massive bomber force that could devastate Italy’s enemies. He bombarded his superiors and senior governmental officials for such an expansion program. Simultaneously, he castigated the Italian army for its ineptitude and unpreparedness.

All this agitation managed only to get him court-martialed and thrown in prison for a year. In 1917, after Italy suffered staggering losses during the Battle of Caporetto, the Italian military released him from his cell and made him central director of aviation at the General Air Commisariat. He continued to be an agitator and drove his superiors nuts with his persistent demands and complete lack of a political filter. He said what he felt, didn’t care who took offense, and flamed out yet again. This time, he resigned from the Italian Army and turned his attention to writing.

In 1921, he published what would become the single most influential book on military airpower for the next thirty years. Seen through the lens of twenty-first-century warfare and the pains Western militaries take to minimize civilian losses, Douhet’s book is nothing short of an apocalyptic vision of societal destruction through aerial bombardment.

Billy Mitchell in the cockpit of a Thomas-Morse Scout. Mitchell was not an exclusive advocate of strategic bombing. He was an advocate of airpower in general and its balanced employment on the battlefield. Abrasive, visionary, devoted to the cause of an independent air service with visceral devotion, he was the army’s ultimate rebel during the 1920s. It cost him his career, but his teaching and influence defined the United States Army Air Corps for generations to come.

Mitchell made national headlines when he unleashed an assault on the navy’s sacred cow: the battleship. In a series of tests, he proved conclusively that aircraft could sink any armored vessel, both with direct hits as well as near misses that shattered hulls with their hammer-like concussion waves. What seems obvious now was not to hide-bound, tradition-impaired elderly flag officers who dominated the upper echelons of the navy during the 1920s. They spent much of the decade trying to marginalize the tests.

The Navy invested millions of dollars into its lighter-than-air program during the 1920s and 1930s. For the most part, it was wasted effort. Rigid airships like the USS Shenandoah, Akron, and Macon had no place on the modern battlefield. The infrastructure to support these massive aerial giants survived their demise to be used in a variety of roles in the decades to come. Here, the massive rigid airship hangar at Moffett Field, California, became home to squadrons of anti-submarine blimps used by the navy to patrol the west coast. The hangar was so huge it developed its own weather systems. It is still in existence today.

Douhet believed that the next war would see armies stalemated in murderous trench fighting once again. As men flung themselves into raining artillery shells and sweeping machine gun fire, Douhet envisioned the ultimate victory would be the nation that devoted its resources toward the construction of an offensive air force. With the deadlock claiming thousands below, fleets of bombers would soar over the front to first secure command of the air. With the enemy’s air units destroyed through bombing of their airfields and production infrastructure, the victor could turn its attention to carpet-bombing cities, communication centers, and vital targets. Kill women, children, the factory workers who built the planes, tanks, and rifles used on the front lines, and the war would be won. Douhet’s cold calculations even called for drenching already stricken cities with poison gas to kill its first responders and security forces as they sought to save trapped citizens and restore order.

It was the ultimate vision of total warfare. No longer would the rifle-armed soldier be in the crosshairs. For Douhet, the answer to World War I’s gruesome toll was to traumatize a society so completely that its terrorized citizens would rise up in revolution, sweep away their government, and sue for peace. The airplane and the aerial bomb would be the delivery system for slaying national morale and resolve to continue the fighting.

When the navy’s airship USS Shenandoah went down in 1925, Mitchell used the event to publically excoriate his superiors in Washington, D.C. Such an assault could not go unpunished, and Mitchell was court-martialed. The trial ended his military career.

Through the 1920s, Douhet’s book gained traction slowly throughout Europe. In France, while some air-minded officers became followers of Douhet, the French military establishment gradually let the L’Armee de L’Air waste away to a skeleton of its former 1918 glory and instead devoted its budget to building the Maginot Line. To the French Army, concrete seemed to be the answer to positional warfare. In Britain, however, the independent Royal Air Force had been searching for a unique role. Douhet’s concepts gave the RAF a raison d’etre and dovetailed with thinking already developing in that service. Hugh “Boom” Trenchard, the commander of the RAF, saw strategic bombing as the saving grace for his beloved independent branch of the British military and used that concept as a way to maintain what slender appropriations were available to national defense through the 1920s.

George Kenney, who would latter gain fame as the commander of General Douglas MacArthur’s Far Eastern Air Forces, had spent much of his career in the 1920s focused on tactical aviation. He innovated and developed a number of tactics and weapons to support such operations. Ironically, he was the officer who translated Douhet’s seminal work on strategic bombing, Command of the Air into English and brought it to an American audience.

In the United States, Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell dominated the nascent air service. Mitchell was one of those officers who generated enormous passion around him. His dynamic leadership and vision attracted many acolytes, including men like Henry “Hap” Arnold and Carl Spaatz. At the same time, Mitchell possessed a knack for alienating his superiors and the politically influential with his blunt talk and willingness to speak his mind. In that respect, he and Douhet were kindred spirits, and Mitchell never backed away from a fight if it furthered the cause of military airpower in the United States.

The early 1930s saw the United States Army Air Corps receive some of its first modern and homegrown aircraft designs. The American aeronautical industry had made tremendous gains after its rocky performance during World War I. Here, a squadron of Martin B-10 bombers sit on a parking ramp at March Field in 1934. Fast and well-armed, the B-10 represented a huge technological leap for the United States and helped pave the way for the superb aircraft that would help win the war.

In 1921, Mitchell took on the U.S. Navy establishment and slaughtered that service’s sacred cow: the battleship. In a series of tests, he proved that aircraft could sink what had been up to that point the foremost expression of military power projection. Mitchell went on to write a treatise on airpower doctrine that he called Notes on the Multi-Motored Bombardment Group Day and Night. In most respects, it was more sophisticated and down-to-earth than Douhet’s grand vision of the future. Douhet didn’t sweat the details; Mitchell, who had commanded a force of almost a thousand planes at the end of World War I, kept his ideas rooted in operational realities. As a result, his doctrine believed that firm cooperation between bomber and fighter groups would be the only way to defeat an enemy’s air force. As a former infantryman, he became the first of the airpower visionaries to integrate combined operations between the two types of combat aircraft.

Unfortunately, before he could mold the U.S. Air Service in his image, his mouth earned him an E-ticket ride into retirement. In September 1925, the U.S. Navy’s airship, USS Shenandoah, went down in a Midwest storm, killing fourteen members of its crew. Mitchell used the disaster to excoriate the defense establishment’s leadership, calling his superiors “criminally negligent.”

The Douglas B-18 Bolo served as the first conceived and purpose-built strategic bomber for the USAAC. It possessed many drawbacks, including a light payload and short radius of action.

Mitchell’s bomb-throwing in the press landed him in front of court-martial board, which ultimately found him guilty of “conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline” despite the fact that many of his acolytes, Arnold and Spaatz included, testified on his behalf. Sentenced to five years suspension from active duty, Mitchell instead resigned his commission, his career over. During the final years of his life, he grew increasingly shrill with his attacks on the army and his agitation for an independent air force along the British lines.

Mitchell may have flamed out just like Douhet, but his ideas had taken root. His devotees proved much more patient and politically adept. In the years that followed, they worked within the system to see much of Mitchell’s vision actually get implemented.

In 1933, George Kenney, who had been one of the few American advocates of low-level tactical bombing, translated Douhet’s Command of the Air into English. The book spread through the Air Corps like a wildfire. At the Tactical School, which had been established in 1931 at Maxwell Field, Alabama, Douhet’s theories soon formed the core of the syllabus taught to an entire generation of aviators. Lieutenant Colonel Don Wilson, the curriculum director at Maxwell, added his own twist that became the signature of American strategic bombing doctrine in the years to come.

A YB-17 Flying Fortress over the Cascade Mountains. Though the B-17 program initially lost out to the cheaper B-18, the USAAC saw so much potential in the design that funds were made available to continue developing it.

Wilson read Douhet and found his total disregard for civilian life to be appalling. Why was it necessary to replace the slaughter in the trenches with mass slaughter in the streets of an enemy’s cities? Instead, Wilson advocated focusing bombing attacks on vital targets. Instead of raining bombs down on urban centers, the Tactical School taught the focused application of bombing against key industrial targets. Along the way, Mitchell’s belief that combined fighter and bomber operations lost favor. The strategic bomber became the be-all and end-all to the U.S. Army Air Corps’s mission for the next war.

A B-10 during a flight to Alaska in 1934.

From that was born the concept of pinpoint bombing, carried out by multi-engined, long-range aircraft that possessed enough defensive firepower to defeat any enemy interceptors launched at them. Through the 1930s, the Army Air Corps strived to develop the tools needed for such a mission. The two critical components—an aircraft with the capability to undertake the mission and a bomb sight that could deliver ordnance on target accurately—came together in the late 1930s with the arrival of the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and the Norden Bombsight. These two remarkable innovations placed the United States on the leading edge of long-range bombing technology just as the war in Europe broke out in 1939. Finally, the airpower advocates had the tools to see their vision realized.