Bombing up an Eighth Air Force Fort prior to a mission in 1943.

I saw a Fort knocked out of the group

On fire and in despair

With Nazi fighters surrounding her

As it flew alone back there.

The Messerschmitts came barreling through

Throwin’ a hail of lead

At the crippled Fort that wouldn’t quit

Though two of its engines were dead.

But a couple of props kept straining away

And her guns were blazing too

As she stayed in the air

In that hell back there

And fought as Fortresses do.

—Anonymous Eighth Air Force crewman, penned while in captivity in Stalag Luft #1. Quoted in Staying Alive by Maj. Carl Fyler

BREMEN WAS ONE OF THOSE TARGETS that made the American bomber crews groan. The factories in Bremen gave birth to many of the Focke-Wulf 190s that intercepted their formations to kill and wound their friends. The Germans ringed Bremen with heavy anti-aircraft guns and a concentration of fighters that made every raid on the city a harrowing ordeal for the Mighty Eighth.

On April 17, 1943, Eaker sent his men against Bremen. Four bomb groups, led by the 91st’s twenty-eight B-17s, formed up over East Anglia and headed for their target. The force totaled 107 bombers. Back at the 91st Group’s base at Bassingbourn, the commanding officer had arranged to host a huge party that evening that included 150 civilian guests and 200 men from the group.

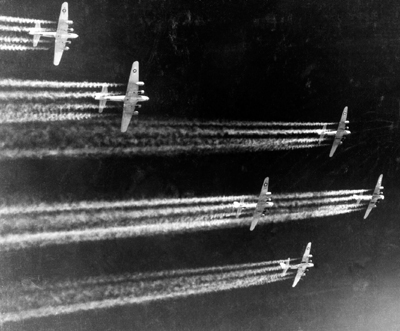

An Eighth Air Force raid en route to Bremen. Bremen was one of the nail-biter missions for the crews. Thoroughly defended by flak and fighters, the city was home to aircraft factories and U-boat construction facilities. Losses on such raids were heavy throughout 1943.

The U-boat yard at Bremen was a priority Eighth Air Force target, one that was repeatedly bombed through 1943 and 1944.

Near the target area, the Germans coordinated a masterful interception. The Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs concentrated on the 91st and made determined head-on attacks against its squadrons. Six of its Forts went down in flames—five from one squadron. Most of the 91st’s remaining planes suffered damage. Altogether, fifteen Forts fell to the German fighters. Another thirty-nine returned home scarred by flak shrapnel, cannon shells, and machine gun hits. Over half the attacking force went down or took damage. It was a desperate and sobering moment for the Eighth Air Force.

At Bassingbourn, the partiers awaited the 91st Group’s return. They straggled in, dead aboard their battered Forts. In horror, many of the guests realized that the men who had invited them had died that afternoon over Germany. As the survivors climbed out of their aircraft, most wanted nothing to do with the festivities.

The party went on. The men showed up, nerves shot from the ordeal they’d just experienced. The mood only grew worse as the alcohol flowed and the evening wore on. The survivors drank away their pain and some got so out of control that the group’s historian recorded the event for posterity, noting that “several of the combat crew members indulged too freely.”

Bremen set the tone for a year of catastrophes and casualties. On June 13, the heavies struck at Kiel and Bremen simultaneously with 182 aircraft. The Germans shot 22 of them out of the sky and damaged another 23. Such losses simply could not be sustained. The crews began to suffer the effects of prolonged exposure to the stress of combat. They had trouble sleeping. They self-medicated with alcohol. Some broke down completely and had to be grounded. A few committed suicide rather than face the crucible of flak and fighters again.

Three days before that dreadful mission, the U.S. chiefs of staff issued the Eighth its marching orders in what became known as Directive Pointblank. Taken straight from the Combined Bomber Operations document Eaker, Hansell, and the British produced, Pointblank called for the destruction of the German aircraft industry and the simultaneous seizure of air superiority over Western Europe. It was a tall order. That summer, the Germans had put their aircraft factories in high gear. That spring, the workers in those plants constructed over a thousand fighters a month. The total Luftwaffe fighter force rose from about 1,600 planes in February to over 2,000 by the start of the summer. Of those, about 800 defended the Reich and its Western approaches from the Eighth Air Force.

Bad weather hampered the execution of Pointblank for over a month. Finally, toward the end of July, the clouds vanished and blue skies greeted the bomber crews each dawn. Eaker seized the moment. In what became known as “Blitz Week” the Eighth flew maximum effort missions for six consecutive days starting on July 25. Hamburg served as the first target of the new offensive. The target had been chosen jointly with Bomber Command in what became one of the first incidents of round-the-clock bombing on a German city. The night before, Bomber Command hit the city with incendiaries and 4,000-pound blockbuster bombs. The next morning, The Eighth attacked Hamburg’s shipyards. Frantic Luftwaffe interceptors pressed their attacks to point-blank range over the burning city and blew fifteen American bombers out of the air. Sixty-seven more suffered serious damage out of the hundred that made it to the Initial Point (IP), the start of the bomb run.

A 95th Bomb Group B-17 struggles through a sky full of 88mm flak bursts over Bremen.

The following night, the British bombed Hamburg again, but thunderstorms disrupted the mission. They tried again on the night of the twenty-seventh, sending 739 bombers through the darkened skies to Hamburg. With the air dry and warm, the incendiary attack created a tornado of fire that stretched a thousand feet into the air. The flames, whipped and propelled by winds of over 150 miles an hour, consumed eight square miles of downtown Hamburg. The firestorm melted asphalt, asphyxiated hundreds of civilians trapped in underground shelters, and burned everything in its path. Witnesses reported seeing the hurricane-like winds sweep people right off the streets and throw them into the roiling flames. Bomber Command hit the city two more times before August 3. When the operation ended, over fifty thousand German civilians lay dead in the smoldering ruins of their city. A million more emerged from their shelters to find their homes destroyed.

Unlike the RAF’s night campaign, there was no hiding in the daylight skies over Western Europe. Early on, the Eighth Air Force crews discovered their aircraft left contrails that could be seen for dozens of miles. Luftwaffe fighters had little trouble locating them once their ground controllers vectored them into the bomber stream’s general vicinity.

A 91st Bomb Group Fort swings low over an airfield in East Anglia after a mission over Europe in September 1943.

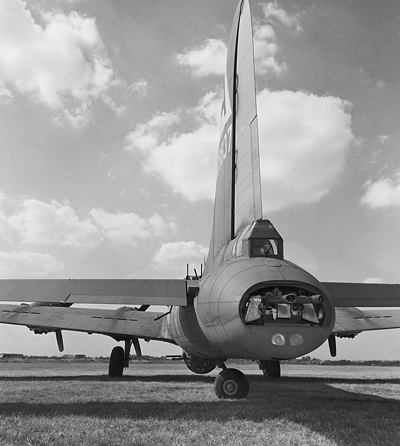

As a stopgap, the Eighth Air Force experimented with YB-40 escort bombers to protect its Flying Fort formations. The YB-40 was an up-armored B-17 loaded with extra ammunition and .50-caliber machine guns. In combat, they proved to be nearly useless and were so laden that they could not stay in formation with the more lightly loaded B-17s after they had emptied their bomb bays. These YB-40s belonged to the 91st Bomb Group.

While Bomber Command devastated Hamburg, the Eighth’s “Blitz Week” continued. On the twenty-sixth, the Forts and Liberators hit Hanover and Hamburg again; 227 American airmen died, went missing, or suffered wounds during those twin raids.

In the first two days of Blitz Week, the Eighth lost 317 men. Eaker did not ease up on the operational tempo. On the twenty-eighth, the bombers struck the Fieseler aircraft factory in Kassel and another aviation plant at Oschersleben. Over three hundred bombers left East Anglia. Twenty-two went down over Europe and over a hundred more returned to England with battle damage. Another 231 airmen became casualties.

During the day’s missions, the Germans unleashed a new surprise on the American bomber crews. This time, deep over the Third Reich, the B-17 formations encountered a formation of Messerschmitt Bf-110 fighters equipped with rocket projectors under their wings. Called the Gr.21, the new weapon was an adaptation of a Wehrmacht infantry mortar. The 110s lurked behind the 385th Bomb Group, their pilots careful to stay out of machine gun range as they launched their rockets. The projectiles shot out of their tubes, soared over the 385th’s aircraft, then fell right into the middle of their formation and exploded. The attack scored a direct hit on a B-17, which spun into two others and sent them plummeting earthward in flames. In a heartbeat, the 385th lost thirty men.

The 351st Bomb Group en route to a target inside Germany during the 1943 campaign.

A target photo showing the 303rd Bomb Group’s tight pattern of 500-pound bombs walking across the hangar and barracks facilities at a Luftwaffe airfield outside of Orleans, France.

Summer at Molesworth Airfield in East Anglia, home of the 303rd Bomb Group. Many of the Eighth Air Force stations were carved straight out of the farmland in the area. The local farmers would continue to work the land surrounding the facilities, leading to fall harvests as the Americans continued the air war against Germany.

Ground crews frequently decorated bombs bound for the Third Reich with typical irreverent American humor.

A formation of Eighth Air Force Forts in 1943. The nose armament ended up being the weak point of the B-17E and F models. When the Luftwaffe discovered this, the best Jagdgeschwaders executed head-on passes through the bomber boxes.

July 29, 1943, saw Eaker send his units against Kiel and the Heinkel factory at Warnemünde. The effort that day claimed another hundred American airmen. And still Eaker would not ease up on the pace. Over a hundred more men went down the next day over Kassel.

So much bloodshed, so many aircraft lost—to what gain? Post strike reconnaissance showed spotty accuracy at best. In order to get their bombs to their intended destination, the Forts and Liberator crews had to fly straight and level from the IP until they reached the target. This usually required flying without any evasive maneuvers at all for at least fifteen miles at a time when the crews usually faced the heaviest concentrations of anti-aircraft fire.

A B-17 navigator at work in his cramped compartment.

Based mainly inside the Third Reich itself, out of range of VIII Fighter Command’s aircraft, the Luftwaffe’s heavy fighters, like this Messerschmitt Me-410, used rockets to disrupt B-17 formations before closing in and picking off stragglers with cannon fire. They were the most effective casualty-producing interceptor in the skies during 1943 and helped tip the scales in favor of the Luftwaffe later that fall.

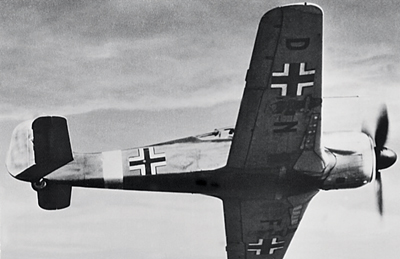

The dreaded “Butcher Bird”—the Focke-Wulf Fw-190A, the Luftwaffe’s most deadly daylight interceptor in 1943. Standard armament included four 20mm cannons and a pair of machine guns firing over the nose. Later, the Germans manufactured underwing 20mm packages that could double the Focke-Wulf’s cannon firepower. In such a configuration, the Focke-Wulf became a deadly bomber destroyer. But those extra cannons came at the expense of maneuverability, however, and if caught by American escort fighters they were easy prey.

Hit by flak over Trondheim, Norway, an Eighth Air Force B-17 falls out of formation over the North Sea. The combat box provided safety and mutual defense. When a damaged B-17 could not keep up with its squadron mates, chances were good marauding Luftwaffe fighters would pounce on them and finish the crippled aircraft off.

A 385th Bomb Group crew drags a damaged Fort home as “meat wagons”—ambulances—await its landing.

“This is It,” a 381st Bomb Group Flying Fort on a bomb run over Mainz, Germany. The final approach to a target area was always the most vulnerable moments for the Eighth Air Force crews. To ensure maximum accuracy, the Forts and Liberators had to fly straight and level for at least fifteen miles while the lead bombardiers located and tracked the target. The Germans recognized this as the killing moments and ringed vital installations with heavy flak batteries. If the flak didn’t actually knock aircraft down, it frequently disrupted formations enough to degrade accuracy.

A B-17 combat box over France in 1943. The German fighter pilots learned to judge which groups were better than others by how tight the pilots stayed in these formations. Less experienced crews tended to fly in looser boxes, which the Luftwaffe would exploit with sudden, slashing attacks at their weakest points.

Shot up and on fire with three engines out, this B-17’s crew managed to limp back to East Anglia and crash-land in rolling farmland, where Eighth Air Force ground personnel caught up to it and began effecting repairs. Such incidents were all too common through the 1943 campaign.

A captured Fw-190A under flight testing back in the United States. The USAAF thoroughly evaluated the Focke-Wulf to learn its weaknesses and strengths so that tactics could be developed to defeat this very effective German fighter.

The tail gunner’s positing in a 91st Bomb Group B-17 at Bassingbourn in 1943. The twin .50-caliber machine guns proved so effective when groups massed into their protective combat boxes that the Luftwaffe interceptors virtually gave up stern attacks.

The Fort’s weak nose armament—a single hand-held .50 used by the bombardier—was soon discovered and exploited by the Luftwaffe’s fighter pilots. To counter their head-on attack tactics, the Eighth Air Force groups began field-modifying their aircraft. In this case, the ground crews of the 91st Bomb Group installed a twin .50 mount in the nose of a B-17 at Bassingbourn in February 1943.

Eaker and Gen. Jacob Devers pose beneath the nose of the most famous Eighth Air Force B-17—the Memphis Belle. The crew of the Memphis Belle became the first to complete their twenty-five-mission tour in England.

In May 1943, Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft and occasional bombing raids on England remained a threat. Here, the 92nd Bomb Group has covered one of its Forts with camouflage netting. Pup tents for the ground crews surround the aircraft.

Morning at Ridgewell, home of the 381st Bomb Group, in August 1943.

Most groups simply abandoned that SOP (standard operating procedure). Even after the IP had been reached, they would change altitude every few seconds to throw off the radar-operated guns below them. The Norden sights could not handle such maneuvers and still make its calculations with any accuracy. Fewer Forts went down, but the targets remained intact, which required return visits to them and more exposure to Luftwaffe interceptors. It was a zero-sum game with the crews caught in a hellish cycle.

In 1942, the average Eighth Air Force bomber crew could expect to survive about fourteen or fifteen missions. Twenty-five completed a tour. Not many did. They faced long odds that year. In the summer of 1943, the odds grew even worse. The average crew survived fewer than ten missions.

As Blitz Week came to its bloody end, there was no doubt who was winning the air war over Germany: the Luftwaffe still controlled the daylight skies.

A pair of 305th Bomb Group B-17s prepare for takeoff at Chelveston in June 1943. The Eighth Air Force had grown strong enough that summer to challenge the Luftwaffe over the Third Reich for the first time. Without a long-range escort fighter to protect them, the Eighth’s bombers took a serious beating.

Caught from behind by an Eighth Air Force fighter, a Focke-Wulf Fw-190 pilot breaks right in a desperate effort to get out of his pursuer’s line of fire. He was a split second too late, and the American’s bullets can be seen scoring hits along the right wing root.