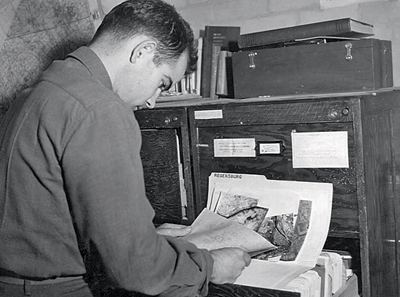

During the initial deep penetration raids over Germany, the bomber gunners discovered they had to watch their ammunition supply carefully. So many fighters would attack their formations that often they’d run out of .50-caliber ammunition. After missions like Regensburg and Schweinfurt, the waist gunners stood in ankle-deep piles of spent brass, a testament to the ferocity of the fighting.

This was to be my 25th mission. I was so battle weary I could hardly function, but I acted. I did what I thought was right. Maybe, subconsciously, I knew it would be over one way or another . . . there were only two of us left from the top squadron.—Carl Fyler, Staying Alive

AUGUST 1943 WAS THE MONTH FOR E-TICKET TARGETS. While Ploesti attracted the Ninth Air Force, the Eighth cast around for something really substantial to bomb. Colonel Richard D’Orly Hughes, VIII Bomber Command’s chief targeting officer, studied his maps and reviewed his lists of aircraft factories and their estimated production levels in search of some German Achilles’ heel the Americans could exploit. He thought he found that weakness in three locations: Schweinfurt, Regensburg and Wiener Neustadt. The aircraft factories at Regensburg and Wiener Neustadt accounted for almost half the Luftwaffe’s fighter production, while Schweinfurt produced half of the Third Reich’s ball bearings.

Could a triple strike hammer all of these choice targets at once? Such an operation would require coordinating with the Ninth Air Force in Libya; Wiener Neustadt was located near Vienna, Austria, and was out of the Eighth Air Force’s range.

Weather issues conspired against such cooperation. When the skies cleared over Western Europe, they clouded over to the south. The Ninth ended up bombing Wiener Neustadt on its own on August 13, 1943. Using the sixty-five remaining Liberators that survived the inferno of Ploesti, the Ninth surprised the Germans with this deep penetration raid. Hardly any interceptors were based in the area and for a change the B-24 crews didn’t take it on the chin. Only a few bombers were lost. The raid failed anyway; the bombardiers missed their targets.

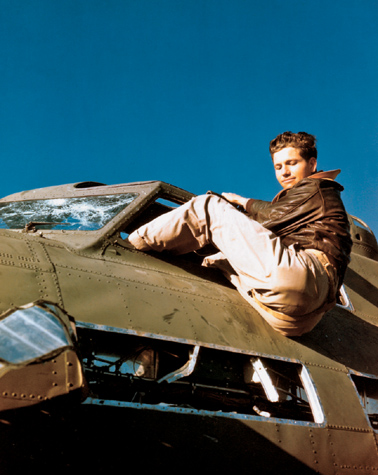

Forts over England. By the summer of 1943, the Eighth Air Force had grown strong enough to attempt deep penetration raids into the Third Reich. The theory of daylight precision bombing would finally be put to the test.

The Messerschmitt Bf-109G was the most common Eighth Air Force adversary over Germany’s skies in 1943. Over thirty-five thousand 109s were built during the war. While an excellent air superiority fighter, the 109 was not a particularly good bomber interceptor. It lacked the firepower of the Bf-110 or the Fw-190, a severe disadvantage when attacking the ultra-rugged Flying Fortress.

That left the Eighth Air Force to tackle Regensburg and Schweinfurt. VIII Bomber Command concocted a complicated and timing-based plan that required a lot of moving pieces to function without normal operational friction. General Curtis LeMay’s 4th Bomb Wing would lead the mission with the elite 96th Bomb Group at the tip of a spear 139 bombers strong. Regensburg would be their target for the day. Located deep inside Germany, LeMay’s B-17s would face the ultimate test: could they survive for hours unescorted in the face of determined Luftwaffe interception? To maximize their chances, LeMay came up with a new type of mutually supporting formation that required three bomb groups. He had twelve total under his command, so he organized them into four tightly-drawn “combat wings,” each with a middle group, a high group, and a low group flying in close proximity to one another. This way, the groups could cover each other’s flanks with their B-17s massed defensive gun power.

The 1st Bomb Wing was supposed to follow directly behind the 4th with a fifteen-minute interval between the two formations. Once over Central Germany, the 1st would veer off to bomb Schweinfurt, hopefully surprising the Luftwaffe’s radar operators with the sudden course change.

The Eighth Air Force targeting specialists searched for weak spots in the German war machine and its industrial base, hoping to locate some key facility that when destroyed could materially affect the war right away.

To further confuse the Luftwaffe, LeMay’s men would not turn back for England. Instead, his Forts would continue southward to land in North Africa. This represented the first of several “shuttle” bombing missions performed by the Eighth.

On August 17, 1943—the one-year anniversary of the Mighty Eighth’s first mission—weather reconnaissance aircraft detected clear skies over the target areas. In England, however, the crews sat next to their B-17s enduring mist, fog, and light rain. LeMay didn’t let that stop him. He’d trained his groups in instrument take-offs, and after a ninety-minute delay, his men gained the sky, formed up into a column some fifteen miles long, and headed for Regensburg.

Curtis LeMay (far right) led the 4th Bomb Wing during the famous double strike mission to Regensburg and Schweinfurt. LeMay’s combat experience in the Eighth Air Force shaped his vision of strategic bombing for years to come. Later, he commanded the B-29 forces in the Pacific and burned Japan’s major cities to the ground. After the war, he forged Strategic Air Command into an elite and highly effective force.

The Germans attacked them over Belgium. Swarms of interceptors swept out down into deadly head-on passes. The Luftwaffe pilots concentrated on the trailing combat wing—the unlucky 91st again along with the 381st. The escorting American P-47s could not handle the German onslaught, and the interceptors broke through their cordon to flame six of LeMay’s B-17s. At the German frontier, the Thunderbolts ran low on fuel and turned for home, leaving the Forts to the depredations of hundreds of German fighters. Before even reaching Regensburg, another eight Forts went spinning down to their destruction.

Bombing from below 20,000 feet, the 4th Wing inflicted considerable damage to the aircraft factories. Later estimates put the production loss at almost a thousand fighters. With their bays now empty, the Forts continued southward for North Africa, a move that did catch the Luftwaffe’s ground controllers by surprise. A few Bf-110s gave chase, shooting down three more American planes.

Early in 1943, the Boeing B-17E began to be replaced by the B-17F. This early Fort arrived in England with an unusual camouflage pattern that resembled the standard RAF disruptive scheme.

Meanwhile, the 1st Bomb Wing did not leave its airfields until LeMay’s had been in the air for five hours. The delay, caused by the weather in East Anglia, set the table for a catastrophe. Once aloft, the 222 bombers in this second wave managed to place a perfect interval between themselves and LeMay’s men—at least from the German perspective. The timing allowed the Luftwaffe’s fighters to land, rearm, and refuel. Some of the 109 and Fw-190 pilots even had time to grab a bite to eat before taking to the air again.

The Luftwaffe’s ground controllers had spent much of the afternoon marshalling resources to really pound the 4th Wing when it headed back to England. Instead of facing off against the 4th Wing, these interceptors turned out to be perfectly placed to devastate the second American wave.

Some three hundred fighters tore into the 1st Wing’s formation. This time, they concentrated on the lead combat box. Seventeen Flying Forts fell out of the sky as the fighters made relentless attacks from all quarters. Over Schweinfurt, the wing had to select a new IP on the fly in order to keep the setting sun out of the eyes of its bombardiers. The last-minute switch threw a monkey wrench into the attack. The crews scattered their bomb loads all over the city.

A 96th Bomb Group B-17 over Belgium. The 96th was one of the Eighth Air Force’s elite outfits, which is why it was selected to lead the Regensburg mission in August 1942.

Fritz Boost, a young Luftwaffe transport pilot, happened to be in Schweinfurt after the raid and saw the damage it inflicted. The bombs had cut neat swatches right through the city, destroying block after block of buildings without causing catastrophic damage to the ball bearings plants located there.

Though production did drop as a result of the attack, the Germans simply made up the shortfall by purchasing ball bearings from the Swedes. Hap Arnold attempted to stop the sale by offering the Swedish government P-51 Mustangs and C-47 Skytrain cargo aircraft, but the Swedes refused the offer and cut a deal with Nazi Germany instead.

Altogether, sixty B-17s failed to return from the Regensburg-Schweinfurt double strike mission. Worse, when LeMay’s men reached North Africa, the landing grounds were so primitive that they lacked even basic maintenance facilities. And the 4th Wing’s Forts needed a lot of maintenance. Most of the ones that reached North Africa had suffered battle damage. LeMay ended up having to abandon sixty non-flyable B-17s in North Africa. Bombing Regensburg cost the 4th Wing 40 percent of its effective strength.

Boeing could not produce B-17s fast enough to support the global effort against the Axis powers. As a result, construction was contracted to a number of other companies, including Douglas and Vega. This Eighth Air Force B-17 was produced at the Douglas plant in Long Beach, California.

That night, Bomber Command flattened Peenemünde, Nazi Germany’s secret rocket research facility. In the process, Luftwaffe night fighters shot down forty RAF bombers. In one day, the Allied strategic forces had lost a hundred aircraft and close to a thousand men. The staggering losses only grew worse.

After the double strike raid, Eaker began to waver. Did the British have it right after all? He decided to explore the idea of converting the Eighth Air Force to night operations. He sent a squadron from the 305th Bomb Group to the RAF to gain experience in nocturnal raiding.

After a short respite, the Eighth increased its operational tempo through September, reaching an almost fever pitch the following month. The intense losses and the constant missions through the spring and summer had already strained the air crews to the limit of their endurance. Some simply could give no more.

Pilot Bob “Spook” Bender came to England in the spring of 1943 as part of the original cadre of the 95th Bomb Group. During a raid on Lorient, Bender’s Fort took a flak hit that knocked out two engines. He dragged the crippled bomber back to England and crashed at the RAF fighter station at Exeter. The B-17 skidded off the runway and took out a highway bridge.

Bender lost two more Forts over the next few missions. Both were so badly shot up by flak and fighters that after he crash-landed back in England they were dragged off for salvage.

On his eighth mission, a raid on the U-boat pens at St. Nazaire, Bender’s fourth B-17 took a serious hit that knocked out an engine. This time, they didn’t make it home. He and his crew ditched off the French coast and spent most of two days and a night riding the swells in a couple of rubber rafts until a British torpedo boat fished them out of the water.

Eight missions, four crash landings. Psychologically, Bob Bender had given all he had to the strategic bombing cause. While off duty, he went to see a movie with some of his squadron mates. The newsreel that evening featured a piece on the USAAF’s bombing campaign and depicted attacks on B-17 formations from Luftwaffe gun camera footage. The sight of the Forts going down caused Bender to start screaming at his gunners to “Shoot! Shoot!” He ducked behind a balcony railing until his friends eased him out of the building.

Two Southerners behind the controls of a B-17. At left is pilot Lt. Bob Boundrecor who hailed from small-town Louisiana. At right is Lt. Ned Hawkins, a native of Jacksonville, Florida.

A few days later, Bender and his crew went to pick up their fifth B-17. As they took off, he froze at the controls and had to be overpowered. Group sent him to a hospital, where he suffered a complete breakdown. He returned to the States, a psychological casualty who never recovered from his ordeal. At age twenty-five, Bender suffered a fatal heart attack.

The crews just had to put their heads down and endure. They counted their missions and prayed that every briefing would reveal the day’s target would be a milk run.

There weren’t any milk runs in the fall of 1943.

In October, the 1943 air campaign over Western Europe reached its climax as the Eighth Air Force flew a series of maximum effort strikes deep into Germany. On the eighth, 400 Forts and Liberators returned to Bremen and Vegesack. They returned less 30 bombers and three hundred more airmen. Another 110 limped back to England with battle damage.

The next day, the groups sortied for Germany again, striking Danzig, Marienburg, Anklam and Gdynia with about 350 bombers. Twenty-eight went down while another 150 suffered damage.

The crowded confines of a B-17’s bomb bay. Sometimes, loading the ordnance could be exceptionally dangerous, and there were cases of bombs exploding. This usually resulted in a lot of casualties.

The next day, the Eighth flew its third maximum effort mission in three days. Most of the bomber crews had already flown at least one of those, and some had flown on all three. This time, the target was Münster. The Americans ran into a Luftwaffe buzz saw, and within minutes of getting intercepted, the 13th Combat Wing’s three groups lost twenty-five planes. The air battle raged all the way to the target and throughout the desperate return to England. Lieutenant John Winant, the son of the American ambassador to Great Britain, was shot down that day while piloting a 390th Group B-17. He managed to bail out and spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp.

A Luftwaffe Bf-109 pilot with his dog in the cockpit with him. As the 1943 campaign wore on, the average quality of German replacement pilots plummeted.

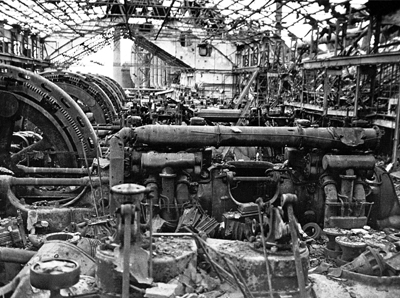

The aftermath of a daylight precision bombing raid. The dead lay within the tangled industrial ruins.

Fritz Boost was a replacement pilot. Trained to fly Messerschmitt Me-323 transports, he was pulled into the Defense of the Reich and taught (briefly) how to fly the Focke-Wulf Fw-190. Fritz had already been shot down on the Eastern Front in a Me-323, ending up in the Black Sea until rescued. Later, as a Focke-Wulf pilot, outnumbered and alone, he was shot down in again in the winter of 1944–1945. After the war, he emigrated to the United States and became a high school teacher.

The end of a Messerschmitt Bf-109, whose surprised pilot did not even have to drop his belly tank.

After the Regensburg raid, LeMay’s B-17s reached North Africa in bad shape. Almost 40 percent of his aircraft had either been shot down during the mission or reached North Africa with major damage that grounded them. He had to abandon sixty non-flyable Flying Forts on his return flight to England a few days later.

Tom Paine was a survivor. This B-17 served throughout the war with the 388th Bomb Group and flew countless missions against Nazi Europe only to be scrapped at war’s end in June 1945.

Had the Fort not been as durable as it was, the Eighth Air Force’s crew losses would have been unsustainable.

General Eaker bore the brunt of the failing long-range penetration effort into Germany. By year’s end, he had been bumped to the MTO, never to receive another promotion. He’s seen here at war’s end as a Soviet official decorates him with a Red Army medal.

This third consecutive deep penetration raid cost the Eighth another thirty bombers and 306 airmen.

Four days later, the Eighth Air Force struck Schweinfurt for the second time. The ball bearings factories proved to be an irresistible lure. This time, the high command held no illusions at how difficult this mission would be on the crews. Word came down from Eighth Air Force HQ that this target could shorten the war if destroyed. The group commanders received explicit instructions to tell the crews this in hopes that it would motivate them.

The aftermath of an air battle. Spent .50-caliber machine gun rounds rattle around in the bottom of a Flying Fort’s fuselage.

Three hundred twenty B-17s and B-24s took off from East Anglia that day. They formed up into their tight combat boxes and drove into the teeth of the Luftwaffe juggernaut. For hours the bomb groups came under fighter attack. Wave after wave of expertly led jagdgeschwaders of Fw-190s and Bf-109s drove their gunnery runs to point-blank range, drilling the American bombers with cannon and machine gun fire. The raid devolved into a parade of slaughter as Fort after Fort went down. Some of the American gunners ran out of ammunition before reaching the target area, so fierce was the fighting. The B-17 carried about seven thousand rounds for its thirteen machine guns, which gave each crewman only a few minutes of firing time for their weapons.

A search and rescue aircraft locates a B-17 that splashed down in the North Sea. A larger boat has been dropped to the crew, who are crammed into a rubber dinghy.

The 100th Bomb Group suffered the worst that day. After the preceding raids in October, the outfit could only field eight B-17s for the Schweinfurt mission. The Germans cut all eight out of the sky. After that, the unit was known throughout the USAAF as the “Bloody Hundredth.”

Once again, Col. Archie Olds and his 96th Bomb Group led the entire force to target aboard a B-17 named Fertile Myrtle III. The 96th endured repeated fighter attack for an hour and half on the way to Schweinfurt, but Olds’ aircraft evaded damage. During the bomb run, their luck evaporated. A flak shell burst next to the bomber’s nose, sending shrapnel into the bombardier’s head and legs. Despite his wounds, he crawled back to his Norden sight and laid his bombs on target.

On the way home, the 96th passed over Reims, where a surprise volley of anti-aircraft fire hit Fertile Myrtle III a second time. The group’s navigator died instantly as shrapnel tore through his back. The bombardier suffered a thigh wound. Olds was blown out of his seat at the same time more shrapnel scythed through the cockpit, wounding two more crewmen. With two engines out, the B-17 entered a dive from 20,000 feet. Somehow, they stayed aloft long enough to get back home and execute an emergency landing. As Olds watched the ground crew remove the bloody remains of the navigator, he said, “Save me a pew in church on Sunday.”

The second Schweinfurt raid cost the Eighth Air Force sixty-seven bombers and almost 650 airmen. The 305th Bomb Group incurred 130 of those casualties, a figure that represented 87 percent of the group’s strength that day. The 306th lost another 100.

The threat of a forced landing in the North Sea or the English Channel was ever present for the Eighth Air Force crews. In East Anglia, the airmen used cast-off or cannibalized wrecks to train for such a possibility.

Shrapnel wounds from bursting anti-aircraft shells inflicted thousands of casualties on American bomber crews. To protect themselves, the men often wore armor plating, some of which was standard issue. Some airmen had the ground crews fabricate custom armored slabs and even codpieces as well.

Often, the bombs would find their mark and destroy much of a factory complex’s structures. Inside, often the vital machine tools, equipment, and generators would survive the onslaught, which allowed the workers to clear debris and get the plant up and running quite quickly.

A waist gunner in action. This was the coldest position in a B-17. With the side windows open to the outside, the temperatures could be as low as sixty below during winter flying at 20,000 feet. Taking gloves off, even for a few seconds, often resulted in frostbite.

In the nose of a B-17F, modified with a pair of .50-caliber machine guns. The bombardier position was not well suited for larger men.

In return, the ball bearing plants took severe damage. Yet, the raid failed to affect the German war machine as hoped. The Third Reich actually possessed a large surplus of ball bearings in the fall of 1943, and whatever more they needed the Swedes readily provided.

Besides, the workers quickly went to work restoring their factories to functioning levels again and within a short time the production rate climbed to pre-attack levels. This represented a major oversight on the part of the prewar strategic bombing advocates. Everyone from Douhet to Trenchard, Spaatz and Mitchell failed to consider that once bombed, a factory could be rebuilt. The Eighth Air Force found itself faced with a multi-dimensional adversary. Not only did the bombers have to fight their way through flak and fighters to reach the target areas, but they had to contend with the workers on the ground who patched up the damage their bombs inflicted.

Ten Knights in a Bar Room, a 94th Bomb Group B-17G, ran afoul of a Luftwaffe Messerschmitt Bf-110 flown by Lt. Jacob Schaus of Nachtjagdgeschwader-4 during a mission to Emden on October 4, 1943. Schaus shot the bomber down, but all ten men managed to get out of their doomed Fort safely. Three became POWs, and the other seven somehow miraculously evaded capture and returned safely to Allied hands.

The 100th Bomb Group earned a reputation as a jinxed unit. During the October Schweinfurt raid, the entire group was shot down. Throughout much of 1943, the Luftwaffe singled out the group and inflicted severe casualties, prompting many rumors and speculation as to why the 100th seemed to receive such treatment so frequently.

A formation of “Bloody Hundredth” B-17s during a mission in the summer of 1943. One rumor that circulated through the Eighth Air Force explained why the Luftwaffe seemed bent on that group’s destruction. During a raid in early 1943, the rumor said, the 100th had machine gunned a German pilot in his parachute after he’d bailed out of his burning interceptor. Word spread through the Defense of the Reich units and the 100th became a marked bomb group. Postwar research failed to confirm any of this. More likely, the 100th flew a looser formation than the other units in its combat wing. The Germans picked up on this and exploited that mistake with relentlessness that led to the deaths of hundreds of American crews.

Me and My Gal, a 384th Bomb Group B-17, became another victim of the Luftwaffe’s heavy fighters that fall. A Ju-88 flown by Uffz. Benno Gramlich caught Me and My Gal over Simmershofen, Germany, during the October 14, 1943, mission and brought it down. Until the Eighth could protect its bombers from the Luftwaffe’s twin engine fighters, deep penetration raids were simply too costly to continue.

Fifty-fifth Fighter Group P-38 Lightnings on the flight line in England. Though a war-winner in the Southwest Pacific, the P-38 never achieved the same level of success in Northwest Europe against the Luftwaffe, leading to its general replacement with P-51 Mustangs throughout the Eighth Air Force.

Alabama Exterminator II, a 384th Bomb Group B-17, is examined by curious RAF personnel.

All business in a B-17’s waist.

Mission debriefing. Landing back in England did not end the day for the Eighth Air Force crews. After securing their bomber, they would gather to go over the details of the mission with their group’s intelligence section.

This meant there would be no knock-out blow, no get rich quick target that could shorten the war or bring the Third Reich to its knees. Instead, the USAAF faced the prospect of a grueling, prolonged campaign to not only knock out their targets, but keep them non-operational with repeated attacks.

Schweinfurt underscored the problem with that reality: the Eighth Air Force simply could not absorb the losses such sustained bombing would require. Unescorted strikes deep inside Germany had failed dramatically and at a terrible cost. It was either time to throw in the towel and join the RAF’s night campaign or come up with something else that could keep the bomber losses manageable.

It was the something else that saved daylight bombing.