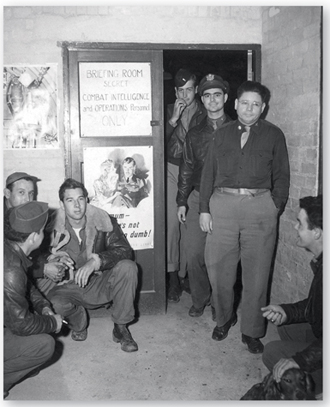

Awaiting the start of a briefing for a mission to Leipzig at the 385th Bomb Group’s base at Great Ashfield.

Fred Derry shook his head and walked a path

From bathroom to dresser . . .

Stopped a while and leaned his elbows . . .

Looked against the glass

And saw the snapshots curling there:

The faces of the 305th.

And some were ringed—

He’d put an inky ring around the ones

He’d seen exploded, frying, going down.

—MacKinlay Kantor, Glory For Me

LONG BEFORE SUNRISE, the duty officer awoke the crews for the day’s mission, moving from barracks to barracks with a flashlight and a list of names. Groggy, weary men, barely removed from frat parties and family farms, arose in the damp velvet darkness of England at war. A shower and shave in cold water followed an indifferent breakfast: powdered eggs, spam, and coffee thick as syrup. The banter would be forced; uncertainty dominated the mess hall. Where were they going today? Would it be a milk run to the French coast? Or would it be a meat grinder like Schweinfurt or Leipzig, Berlin or Bremen? To the men who would soon mount up in the aluminum depths of their Liberators and Forts, the fickleness of their lot seemed both cruel and capricious. The decisions made above them at wing or command HQ held little reason, only dread thinly concealed with crude jokes and camaraderie.

The men of the 305th. Fred Derry was the main character in MacKinlay Kantor’s poetic novel, Glory For Me, which was written just after the end of the war. Instead of creating a fictional unit for Derry to have flown with while in the Eighth Air Force, Kantor went for added realism and used an actual unit. Glory For Me became the basis of the enduring classic film The Best Years of Our Lives, which probed the effects of combat on three veterans after they returned home from the war.

Breakfast finished, the officers departed for their briefing. It was here that the suspense would be lifted. They sat in wooden chairs clad in their A-2 flight jackets, boots and khaki pants, waiting for the group commander to stride into the room and stand before his men. Elmer Bendiner wrote of this daily ritual in The Fall of the Fortresses: “We sat as if in school assembly. The death’s-head-and-crossed-bombs insignia on our leather jackets and the pistols dangling from our belts lent a boyish wickedness to the scene.”

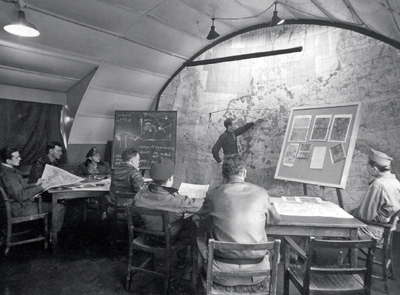

Inside the 385th’s briefing room. At the back of the room, behind the table and chairs, is a screen for projecting slides and film. It was here that the crews assigned to the day’s mission would learn the target they were to bomb.

Once the group commander announced the target for the day, the intelligence officer would usually walk through the planned mission in detail, using a huge wall map of Europe to illustrate the critical elements of the raid.

Course to the target was usually denoted by a red ribbon or string. The longer it stretched into Nazi-held Europe, the more groans and sounds of angst would arise from the audience.

When the commander arrived, the room went silent and the tension immediately spiked. Behind their old-man facades, these boy-warriors prayed for an easy mission. The daily toll of deep strikes had left them weary. The strategic air war had become a test of human endurance, and all had known men whose character could not withstand this test. They failed in odd and sometimes dramatic ways. Those who kept slogging aged well beyond their tender years as friends died or came home in shattered blood-stained bombers, their bodies burned, torn or disfigured by shrapnel and bullets.

They’d long since learned that the glory they saw back home on small town silver screens simply did not exist in the skies over Germany. Physically and psychologically, the strategic bombing campaign was a death march that only the luckiest and strongest would survive.

The group commander would make a few introductory comments. Perhaps he’d crack a joke to ease the tension. But then, it was down to business. “The target for today is . . . ”

For America, the strategic bombing campaign may have been planned in the prewar era by professional USAAF officers, but it was carried out by average young men from all walks of life, most of whom had never set foot in an airplane prior to the Pearl Harbor attack.

Behind him, a map would be concealed until this moment. Operational security was taken very seriously, so the mission’s destination would remain a closely guarded secret for as long as possible.

The map would reveal relief or angst. The officers seated in those wooden chairs cheered or groaned as they greeted the news. Milk run or flak trap. Fighter escort, or go it alone. Colored lines denoted the ingress and egress routes. The time hacks each squadron would be required to meet were carefully reviewed and noted.

At times, the mission requirements left some of the men in attendance with greatly troubled hearts. These were young Americans, steeped in the traditions of their family’s religion. Had not Pearl Harbor been savaged in a surprise attack, most would have passed their years in ordinary anonymity devoid of violence or unnatural death. Instead, circumstance led them to this place where they were expected to kill their enemies without question or remorse. For some, the philosophical or spiritual beliefs they cherished conflicted with their duty at hand.

For some of the air crews, the campaign against Germany elicited moral concerns. Massive bombing of cities, cloaked in terms like “precision bombardment” could not help but produce massive civilian casualties. To some of these young men, this was an extremely difficult mission to carry out.

The Münster raid broke from the doctrine of precision bombing on industrial targets. For the first time, the Eighth Air Force deliberately placed a civilian workforce in the Norden’s crosshairs. Here, the 94th Bomb Group plods its way to the target area, where 30 out of the 236 bombers that reached the target would be lost. Four days later, the Eighth Air Force launched the famous double strike raid on Schweinfurt and Regensburg, culminating what became known as Black Week. Today, the United States officially celebrates this grim period in aerial history with National Eighth Air Force week, October 8–14.

In one early case, the Eighth Air Force laid on a strike against Münster, a key choke point in the industrial Ruhr Valley’s railroad network. The target stripped away any pretense of precision, pinpoint bombing designed to minimize civilian casualties. Rather, the Münster raid’s purpose was the very opposite. Time over target was picked to be the moment church got out on a Sunday morning in October 1943. The medieval cathedral in the heart of the city was designated as the aiming point. Eighth Bomber command wanted to kill as many employees of the nearby railroad marshalling yard as possible, thus hindering attempts to repair the tracks, a fact that was briefed to the B-17 crews of the 95th Bomb Group the morning of the raid.

After the officers completed the morning briefing, they rejoined the rest of their crew and pushed down all the relevant information to them. Not long after this photo was taken, the 381st Bomb Group B-17G Button Nose took a flak hit over Caen on August 8, 1944, and went down in flames.

In the predawn hours before a mission, final preparations are made on a 91st Bomb Group B-17G.

Shrouded in fog, a B-17 awaits its crew at Bassingbourn. Ground fog played havoc with the bomber groups during take-off. Forming up in this sort of thick soup was also quite dangerous and led to many aerial collisions.

Sitting in the audience that day was the 95th’s lead navigator, Capt. Ellis Scripture. In Ian Hawkins’ excellent work, The Münster Raid, Scripture remarked:

I’d been raised in a strict Protestant home. I was shocked to learn that we were to bomb civilians as our primary target . . . and that our aiming point was to be the front steps of the Münster Cathedral at noon on Sunday, just as Mass was completed. I was very reluctant to fly this mission.

Scripture’s qualms were in the distinct minority. Most of the aircrews settled into their grim and violent jobs and did as they were told. In this war, the gloves had come off a long time ago, and every mission they found themselves in a bare knuckled brawl with the best interceptor pilots the world had ever seen. After experiencing that, charity and mercy became early casualties.

After the group commander and his intelligence officer briefed the final mission details, the men dispersed to go brief the rest of their crews. The enlisted men and NCOs who formed the majority of each bomber’s human complement would be found killing time playing poker or reading, or writing a final letter home. Anxiously, they crowded around their pilot, who served as the plane captain and was responsible for all of them. In these minutes, the pilot pushed down the information his crew would need to execute the mission. Once that was done, the men would settle in to wait for the go-order.

The crew of a 95th Bomb Group B-17G rolls to their aircraft prior to a mission in 1944.

That wait could grow interminable, thanks to the European weather. Reconnaissance planes over the target area transmitted last-minute details back to England, including updated weather reports. Many times the target might be clear, but the airfields in East Anglia or the Foggia Plain would be blanketed with fog. Other times, the fields were clear but the targets were obscured. Prewar strategists had never seriously considered something as mundane as weather into their conceptualized bombing campaigns. Here on the front lines, it served as one of the great limiting factors on what the bombers could actually achieve. Missions were scrubbed almost every week thanks to storms over the home airfields or cloud cover over the target area. Come fall and winter, clear skies grew increasingly rare. Snowbound bombers sat in their revetments, the air war on hold thanks to the power of Mother Nature.

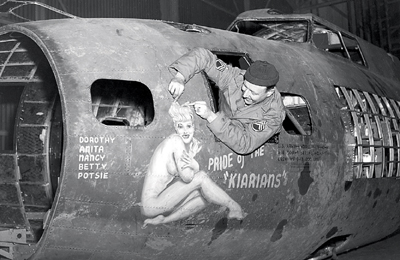

Nose art ranged from the sublime to the raunchy and serves as a window into the sociological climate of the USAAF during World War II. Lesser known than nose art is the personal additions other crew members, both ground and air, made to their bombers.

The crew of a Fifteenth Air Force B-24 arrives for the preflight check and routine.

Waiting for the go-order was always tension filled and difficult.

On most days, the crews assembled and drove out to the flight line to their assigned bombers. The Army Air Forces took a lenient attitude toward individualizing aircraft, and the crews took advantage of that. The talented artists in each group painted artwork on the nose, while the crew or pilot selected a name for their aircraft. Away from home, restraint and taste frequently did not factor into the name or the artwork. Naked women abounded, buttressed by dirty names and ribald humor. In some cases, the aircraft’s name mirrored the type of humor, music, or entertainment the crew enjoyed. In fact, nose art and plane names served as a wellspring of sociological information about the men who flew the bombers.

The customization did not stop with the name or the nose art. The gunners, navigators, and other crewmen frequently added their own touches on the fuselage around their position. A motto, a name that meant something to the man behind the weapon, or swastikas representing interceptors downed and aerial firefights won gave these men a greater sense of ownership in their aircraft.

Inside the bombers, the group’s armorers had already cleaned, oiled, and installed the defensive weapons and filled the ready ammunition boxes with as much lead and brass as they could hold.

The pre-mission checklists were long. As the briefed take-off time approached, the crews would work through their lists. The ground crews had already done much of the work. The machine guns were cleaned, oiled, and installed. Ready ammunition for each position had been placed inside their aircraft. The bombs to be dropped that day already sat snug in the bomb bays.

Once the work was done, the checklists reviewed, the men settled down to wait once again. If weather delayed the mission, this could be the worst time of all, especially if the target was a tough one. Idle time meant time for the brain to engage and think about what was soon to come. And yet, uncertainty often persisted. Would weather delay the mission or scrub it altogether? They hung on tidbits of information passed along from crew to crew as they sat with their gear in the damp grass beside their planes. Not a few threw up as the tension manifested physically in them.

When the bomb groups received the go-order and the mission began, Wright Cyclone engines and Pratt & Whitneys roared to life. Hundreds of them merged together to create a unique sound that resonated for miles across the countryside.

The lack of control over one’s own fate was among the most difficult psychological aspects of the strategic air war. A crew could perform their functions flawlessly and still be blown out of the sky by flak or fighters. A random anti-aircraft shell, fired from five miles below by an illiterate conscript could kill a dozen Americans in an eye blink. A mechanical failure could cripple the unlucky bomber and force it out of formation, leaving it terribly vulnerable to the predacious interceptors that thrived on such easy pickings.

The sheer randomness of who lived and who died created a unique dynamic within the ranks of the strategic bomber crews. That sense of helplessness and inability to control their fate caused many of the men to become superstitious. Comfort was found in rituals and routines considered “lucky,” and many of the men carried small talisman with them into the air. Such behavior served as a psychological safety valve.

That sense of helplessness created a whole subculture of superstition. If one routine worked and the crew returned home, it would be duplicated for every mission thereafter. The men clung to lucky charms and placed their faith in a higher power. In a 1984 NBC documentary called All the Fine Young Men, Elmer Bendiner recalled:

We resorted to magic . . . you pick up talisman. If you do one thing and you come home that night, well that’s the thing to do. Whether it’s the way you tie your scarf around your neck or the socks you put on your feet. It’s a kind of do-it-yourself superstition—you make it up as you go.

The veterans had long since ritualized their routines. The new crews, the replacements who’d never encountered such tension or psychological pressure, learned from the old hands. If they survived.

The go-order roused the men to their feet. The savvy ones emptied their bladders right there around the aircraft, for the missions could last upwards of ten hours as their groups plodded across Europe at 170 miles an hour. One by one, they swung themselves through the forward hatch or climbed into the bomb bays to take up their assigned stations.

Engines turned over. The ground shook as the big radials roared to life. One bomb group typically included over a hundred engines, and they could be heard starting up for miles across the English and Italian countryside. The locals living nearby always knew a mission was on when the ground began to shake and windows rattled in their frames. Frequently, on Sunday mornings, the civilians would fill the pews in the local churches, and the sudden cacophony of the Pratt & Whitneys would drown out the pastor’s service.

Back at the fields, the danger began. From the moment the chocks were pulled away from the main wheels, the risk of death or grievous wound came from a myriad of sources. Just taxiing to the runway could be dangerous, especially in foggy conditions. Ground collisions between B-24s and B-17s were not uncommon. Such calamities often led to mass casualty events right there at the home station as fuel burned and bombs cooked off in the wake of such accidents.

Taking off was the next gut-check moment. The crews were taught to launch thirty seconds apart. Often, this was achieved either in fog or in pre-dawn darkness. If a fully loaded bomber crashed as it sped down the field, sometimes the aircraft behind it would not know it. They’d begin their take-off rolls only to drive right into the flaming ruins of the preceding bomber.

With the engines started, the bombers would then taxi to the runways. From this moment on, the potential dangers and chance of sudden death were many and varied.

The 381st Bomb Group lines up for take-off. In such a crowded environment, catastrophic accidents were depressingly common.

Collisions on the ground while taxiing claimed many aircraft and lives. Here, a pair of 401st Bomb Group B-17s ran into each other in the typically foggy morning conditions in England.

Two fatal accidents. When loaded with fuel, bombs, and ammunition, the bombers were explosive tinder boxes, terribly vulnerable to destruction should something go wrong on the runways during take-off.

To make it easier for the pilots to find their groups amid the aerial chaos over Southern Italy or East Anglia, the USAAF developed garishly painted and easily identifiable “circus ships” that were used as aerial rally points for the groups to use as they linked up after take-off. They represent some of the most outlandish paint schemes ever employed by American aircraft.

The finished product: Formed up and ready to go, the 381st Bomb Group heads east toward the hostile skies of Nazi-held Europe.

Once airborne, the risk of collision actually increased. Forming up by squadrons and groups into the tight combat boxes took time, skill and precision. Again, the weather often played havoc with such a delicate operation. To make things easier for the pilots, each group used a “circus ship” to help assemble their formations. Usually, these were outdated or war-weary B-24s or B-17s that had been painted in garish, easily recognizable ways. That way in the crowded skies over England and Italy, the men could tack on to their circus ship as it orbited. Once assembled, the squadron and groups would then merge with their neighbors until finally the entire wing had formed up. The gunners would test fire their weapons over the Channel or North Sea, the pilots would concentrate on staying tucked in tight as their flights bounced and bucked in turbulence and prop wash. The North Sea and the Channel served almost as the strategic war’s no-mans-land. They represented the last stretch of real estate not dominated by the Third Reich. Once the coast appeared, the battle would be joined. It was time to meet the enemy.