78th Fighter Group P-47 Thunderbolts prepare for an escort mission over Germany. As long-range drop tanks became available, the Eighth Air Force’s Thunderbolts were able to extend their reach deep into Germany—so deep that before the end of the war P-47s flew escort missions all the way to Berlin and back.

“Our little band grows smaller and smaller. Every man can work it out for himself on the fingers of one hand when his own turn is due to come.” –Heinz Knocke, Luftwaffe fighter pilot

THE FALL’S DEBACLES FINISHED OFF IRA EAKER. At the end of 1943, Arnold recast the command structure in Europe. Eaker went to the Mediterranean and never received his third star. In his place, Jimmy Doolittle took over the Eighth Air Force. Spaatz became the overall commander of U.S. Strategic Forces Europe, which included both the Eighth and the freshly established Fifteenth Air Force in Italy. The Eighth would be the left hook; the Fifteenth would be the uppercut. Together, Spaatz could use both to batter the Third Reich into submission.

In England, changes were afoot. Doolittle inspected his new command and raced around East Anglia meeting the bomber and fighter crews. Toward the end of January 1944, during a familiarization trip over to VIII Fighter Command Headquarters, he walked into Gen. William Kepner’s office and saw the sign hanging on the wall. Doolittle read it over, “The first duty of the Eighth Air Force fighters is to bring the bombers back alive.”

Doolittle didn’t like it. He asked Kepner the source of the sign. Kepner told him that it had been something Gen. Frank Hunter had put up in the office in 1942.

“Take it down,” Doolittle ordered. He told Kepner to post another one in its place that read, “The first duty of the Eighth Air Force fighters is to destroy German fighters.”

When the Fifteenth Air Force was activated at the end of 1943, Spaatz took overall command of the strategic air war in Europe. He drove Doolittle relentlessly to prosecute the campaign at all costs.

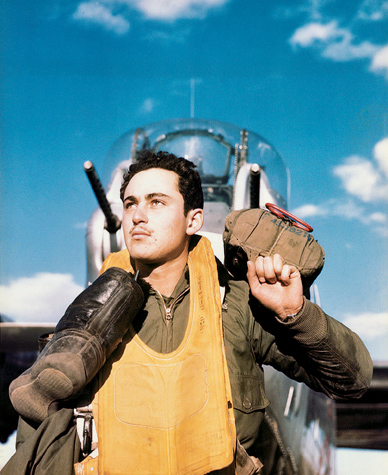

When Doolittle became the Eighth Air Force’s commanding officer, he embarked on a whirlwind tour to meet his men and his units. Here, he gets a short brief on the M2 .50-caliber machine gun during one of his stops in East Anglia.

Kepner loved this. It signaled a new approach to the use of his pilots. In the ensuing weeks, Doolittle made it clear he wanted Kepner’s fighter jocks to channel their inner aggressiveness. In the air, their restrictions were removed. No longer would the fighters be chained to the bomber stream, unable to pursue fleeing German aircraft below 18,000 feet. Indeed, Doolittle made it clear that if the Luftwaffe’s fighters were not pursued relentlessly, VIII Fighter Command was not doing its job.

At the same time, Arnold and Spaatz took a hard look at the failure of Pointblank with an eye on the upcoming invasion of France, scheduled for the late spring of 1944. In a sense, it was the Battle of Britain in reverse. Without air superiority over the battlefield, D-Day would be a disaster. A sense of urgency pushed both men forward. The Luftwaffe had to be destroyed, and they had five months to do it. Arnold told Spaatz to get it done in the air, on the ground, or by knocking out the factories that produced the Luftwaffe’s interceptors.

General Jimmy Doolittle took command of the Eighth Air Force after running Twelfth Air Force in the Mediterranean Theater.

With the arrival of the Mustang and the new long-range drop tanks, the escort fighters held the keys to victory. American intelligence consistently underestimated Germany’s aircraft production, sometimes by as much as a factor of four. Even so, it became obvious to Spaatz and his staff that no matter how many bombers landed on Luftwaffe factories, its front line units would not be hurting for replacement interceptors anytime soon. Doolittle noted this as well, stressing that fuel and aviators were the Luftwaffe’s major limiting factors. And in early 1944, the American strategic forces went to war against Germany’s fighter pilots.

Adolf Galland, the Luftwaffe’s General of the Fighters, had patched together a formidable interceptor force in the fall of 1943 by stripping other commands to keep his fighters in the air. He grabbed pilots out of army co-operation squadrons, weather recon units, and bomber geschwaders and straight from training schools to keep warm bodies in his cockpits. It had been a near run thing that fall, but thanks to the awesome bomber-killing power of the Messerschmitt Bf-110, Ju-88G and Me-410 Hornet, the Luftwaffe retained control of the skies over the Reich.

William Kepner replaced General Hunter as head of VIII Fighter Command. When Doolittle took over the Mighty Eighth, he went to Kepner and ordered him to go after the Luftwaffe with his fighters. It represented a major shift in strategy, one that played a key role in defeating the German Air Force in the months before D-Day.

The equation changed in early 1944. First, Galland’s heavy twin-engine fighters proved virtually helpless against aggressive P-47, P-38, and P-51 pilots. They served a useful purpose only as long as they did not have to contend with American escorts. Now, the heavies had no safe place to operate. The Fifteenth’s and Eighth’s fighters could roam to the far corners of the Reich, negating one of the biggest bomber-killing weapons the Luftwaffe would have in the air war.

56th Fighter Group armorers load .50-caliber ammunition into Francis “Gabby” Gabreski’s P-47 Thunderbolt. The Jug carried eight machine guns, a devastating amount of firepower that could savage German fighters and ground targets alike.

Second, Galland’s pilots had been given a virtual free pass in 1943. With VIII Fighter Command chained to the bombers, the German fighters could dictate the flow of air combat over the Reich. They’d launch their attacks and run for home, confident that the Americans would not pursue them. That changed on January 24, 1944, during an Eighth Air Force mission to Frankfurt. The escort fighters roamed the flanks of the bomber stream, searching for targets. In a running battle that spread all over Germany, the Americans knocked down twenty-three interceptors and lost nine fighters and only two bombers.

The Eighth needed more days like this. To secure air superiority over Western Europe before D-Day, the Luftwaffe had to be drawn out and destroyed in battle. Spaatz and his staff studied the target lists with a new eye: what would make Galland’s men come up and fight?

Goering conversing with Adolf Galland (right) and ace Walter Nowotny on the status of the Luftwaffe’s fighter force. By 1944, the Luftwaffe’s jagdgeschwaders had been stretched to their breaking point by combat casualties and aircraft losses. Continuing the brutal war of attrition over the Reich required cutting many corners in training to get new pilots into the cockpits. It also required stripping other branches of the Luftwaffe of some of their pilots, diminishing the German Air Force’s capabilities as a result.

Defeating the heavy fighter menace during deep penetration raids played a key role in cutting down bomber losses. With Mustangs and Thunderbolts able to roam deep into the Third Reich, the Bf-110s, Me-410s, and Ju-88s could not survive in the sky without the Luftwaffe providing an escort force of Fw-190s. It was a unique situation having to divert interceptors to protect other interceptors, and it degraded the Luftwaffe’s ability to knock planes down.

The American fighters became so aggressive that they followed their prey down to the deck and sometimes to the ground. Here, an VIII Fighter Command pilot strafes a Bf-110 he’s brought down, sending a German crewman diving for cover. Such aggressiveness ensured the Luftwaffe’s defeat over its own country.

From its rocky start as a marginally effective, short-ranged fighter, the Republic P-47 developed into the VIII Fighter Command’s workhorse. The Thunderbolt scored more kills and served longer in combat than the Mustang in the ETO, and thanks to long-range tanks and better pilot training in fuel management, it could operate over most of Germany by war’s end.

What emerged was Operation Argument, a massive, sustained bombing campaign focused on German fighter airframe construction and ball bearings. In a sense, it was simply a modified version of Pointblank. This time, any damage done to the ground targets was simply a bonus. The real target was the Luftwaffe’s interceptors sent up in response to the incoming waves of aircraft. The bomber crews would be the bait. The Mustangs and Thunderbolts would be the trap. The stage had been set for history’s largest attrition-based air campaign.

Argument kicked off with a massive RAF raid on the night of February 19–20, 1944. While the 730 bombers burned out vast stretches of Leipzig, the attackers paid a terrible price. German night fighters and flak teamed up to destroy 78 British aircraft, and 569 RAF airmen were lost in the epic nocturnal duel.

The next morning, the winter weather cleared enough to get the Eighth Air Force into the air. The Liberators and Forts struck at aircraft factories at Leipzig, Gotha, and Brunswick, very selectively targeting the Bf-109, Bf-110, Fw-190, and Ju-88 airframe production facilities there. The Germans could have no doubt; the Eighth was coming after the Defenders of the Reich.

The day cost Galland’s units fifty-eight fighters. In return, the Americans lost twenty-one bombers and four fighters. Big Week kicked off with a tremendous success.

A lone B-17 picks up a friendly P-38 as an escort for a homebound journey.

The Fifteenth Air Force played a supporting role in Big Week. Still a nascent organization, these Italy-based aviators and bombers lacked the numbers and the escort strength enjoyed by the Mighty Eighth. As a result, through February, the Fifteenth’s long-range missions to heavily defended targets in Austria, Southern Germany, and Eastern Europe proved quite costly. Here, a Fifteenth Air Force B-17 goes down in flames after getting hit by flak.

The following afternoon, Doolittle’s men returned to the heart of Germany and destroyed numerous targets around Brunswick. Thirty-two German fighters were written off by nightfall. That night, Goering called a conference with all his Reich defense commanders. The previous two days alarmed the Reichmarshal. The Americans had inflicted severe damage to the production lines that kept his forward units fighting. He wanted to know what his commanders could do to stop it. The conference resulted in some organizational changes that streamlined the operational chain of command. It was also agreed that when launching attacks against the bombers, the Luftwaffe would need to mass its strength in order to break through the ever-thickening layers of American escort fighters. Once massed, at least one jagdgeschwader needed to be assigned to attacking the escorts. Theoretically, this would give the other units a hole through which to attack the bombers. Previous orders had stressed the need to avoid American fighters and focus all efforts on the heavies.

Some of the most heavily defended targets in Germany lay within the Fifteenth Air Force’s area of responsibility.

On February 22, the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces flew their first joint mission. Almost 1,400 B-17s and B-24s thundered over the Reich, escorted by nearly a thousand white-starred fighters. The Luftwaffe threw itself at the oncoming formations. Running battles raged all across the Reich. Bad weather hampered both sides, resulting in wholesale aborts, operational accidents, and sudden encounters with the enemy in the cloud-dominated skies. General LeMay, who now commanded the Eighth Air Force’s 3rd Bomb Division, noted the number of catastrophic collisions among his B-17s as they struggled to form up in the thick soup and ordered a full abort. The B-24s in the 2nd Bomb Division also received the abort signal, but not before some of them had already reached the Continent. The Liberator crews looked for targets of opportunity to bomb, which led to an unfortunate incident where one very lost B-24 crew dropped its payload on England. Another B-24 formation targeted Nijmegen, Holland, with deadly accuracy, mistaking the Dutch city for a German one. The misplaced cascade of falling high explosives and incendiaries killed 850 civilians.

The 1st Bomb Division performed the best that day. Part of the B-17s from the 384th and 303rd groups reached Aschersleben and virtually destroyed the Ju-88 factory there. The extensive damage cut production in half for the next sixty days.

Over Bernberg, the 306th Group bombed another Ju-88 plant, scoring numerous hits. But as they sped for home, they ran into a swarm of Luftwaffe fighters. The interceptors raked the group’s combat box and chased them two hundred miles back to the Dutch coast. By the time the last one made its run at the 306th, the beleaguered Americans had lost seven Flying Forts. The remaining twenty-three had all been shot up.

Torn in half by a direct flak hit, a B-17 spins earthward. During the titanic air battles in February 1944, such sights—and the loss of the ten men inside those aircraft—were depressingly common.

A 15th Air Force B-24 gunner after a mission.

Frantic ground crewmen fight to snuff the flames out on a stricken 401st Bomb Group Flying Fort.

The Luftwaffe wrote off another fifty-two fighters by sunset. Forty-one Forts and Liberators went down—16 percent of the Eighth Air Force’s bombers—along with eleven VIII Fighter Command aircraft. The Fifteenth Air Force suffered 10 percent losses. It had been a brutal day for the USAAF.

Doolittle wanted to give his bomber crews a break. He reported to Spaatz and his operations chief, Maj. Gen. Fred Anderson, that his overtaxed airmen were subsisting on a diet of “Benzedrine and sleeping pills” to keep functioning and flying. Spaatz and Anderson vetoed the break. Anderson in particular believed the Doolittle consistently lost sight of the mission as a result of his attachment to his men. The strain between the two generals would grow in the days and weeks ahead.

Weather ended up scrubbing the scheduled missions for the twenty-third, so the Mighty Eighth’s airmen did get a break. But then again, so did the Luftwaffe’s exhausted fighter pilots, some of whom had been flying three or four missions a day in skies crowded with American aircraft.

On February 24, the Americans returned, flying missions to Schweinfurt again and the aircraft factories in the cities of Gotha, Kreising, and Posen. The winter weather hampered operations once again. LeMay’s 3rd Bomb Division was supposed to hit targets along the Baltic coast in a very daring, unescorted strike. When the Forts got to their assigned areas, layers of clouds obscured the primary targets. Instead, the bombers turned for the city of Rostock and pummeled it before heading back over the North Sea for home.

The B-17s of the 1st Bomb Division found blue skies over Schweinfurt that miraculously were devoid of marauding Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs. The bombardiers took advantage of the opportunity and blasted the ball bearings factories there until little more than rubble remained.

Few targets were better defended and more dangerous for the Fifteenth Air Force than Vienna. Here, a Fifteenth Air Force Liberator struggles through a sky full of flak after getting hit in the right inboard engine.

Fifteenth Air Force B-24 over Italy during a mission in 1944.

If the Forts found the day’s missions easier than expected, the Liberators of the 2nd Bomb Division paid the price for their easy entry over Germany. The Luftwaffe’s ground controllers vectored the bulk of the available fighters at the B-24 stream heading for Gotha. Eighty minutes from their Initial Point, the Luftwaffe pilots swarmed over the leading Liberator groups.

The 389th Bomb Group formed the tip of the divisional spear. In a freakish twist of fate, as the Liberator crews battled their way to Gotha’s Bf-110 factories, the group’s lead aircraft suffered an oxygen system failure. As the B-24 veered out of formation, the bombardier passed out and accidentally toggled off his bombs. The rest of the group followed suit and missed the factories completely. Moments later, the interceptors waded into the group and flamed six of the silver-winged Libs.

A battle-damaged Thunderbolt after crash-landing back in England. When the VIII Fighter Command began hitting airfields, trains, and other ground targets, such efforts drew considerable light and medium anti-aircraft fire that took a steady toll on the attacking aircraft.

Smoke and flames rise over a target area as a B-17 combat wing reaches its release point.

A formation of Fifteenth Air Force B-17 Flying Fortresses over Eastern Europe in 1944. This photo achieved a measure of fame when it appeared in the movie The Best Years of Our Lives. In one scene, Dana Andrews’s character, Fred Derry, shows his war bride this photo, and she was so clueless to what he experienced she asked what the little black clouds were.

Behind the 389th came the 445th Bomb Group. They stayed as tight as a Liberator outfit could, the gunners tracking incoming fighters and snapping out short bursts at them. The Germans proved relentless, using everything from cannon and rocket fire to aerial cables and air-burst bombs to try to bring the Liberators down. One by one, the group’s B-24s caught fire and fell out of formation. Others limped along, streaming thick tongues of black smoke behind savaged engines. By the time the survivors limped home to England, thirteen of the 445th’s twenty-five Liberators were little more than smoking craters on the Continent. Of the remaining twelve, nine had been heavily damaged.

The 392nd, another B-24 group, somehow managed the best bomb run of the day despite repeated fighter attacks. The group’s bombardier put 98 percent of the unit’s ordnance within two thousand feet of the Bf-110 factories at Gotha. It was one of the best operational examples of precision bombing of the war, but the 392nd did not get away unscathed. Seven of its B-24s went down in flames.

To the south, the Fifteenth Air Force struck an aircraft plant at Steyr, Austria. The long-range mission from Italy cost the Fifteenth 20 percent of the bombers dispatched. Altogether, Spaatz’s two air forces lost over seventy bombers. The Luftwaffe wrote off about sixty of its interceptors.

Doolittle looked around East Anglia and saw nothing but burnt-out airmen, bullet scarred bombers, and ground crewmen working round the clock to patch planes together for the next mission. Once again, he begged Anderson and Spaatz to give his men a break.

Anderson told him to shut up and do his job. The targets for February 25 included Regensburg, the huge Messerschmitt 109 plant at Augsburg, plus the ball bearings factory in Stuttgart. It would be another maximum effort, a two-air-force strike.

The Fifteen Air Force drew the Regensburg mission. About 140 of its bombers reached the target, only to be assailed by flak and fighters. Thirty-nine of its Forts and Libs went down—a brutal 20 percent of the attacking force.

The Eighth followed up the Fifteenth with a hundred-Fort raid on Regensburg later that day. This move caught the Reich’s defenders by surprise and the Americans found the skies far less hostile than they were earlier in the day. The heavies utterly destroyed the Bf-109 factory there in another remarkable display of accuracy.

Altogether, the day cost the USAAF another seventy four-engined bombers. The Luftwaffe suffered just as hard, and had started to run out of fresh bodies to fill the cockpits of the available interceptors. In fact, the commander of the I Fighter Corps subsequently wrote, “In the long run, our forces are fighting a hopeless battle.” When February finally drew to a close, the Luftwaffe’s fighter force had lost a total of 434 pilots, almost 18 percent of its total strength. The daylight battle over the Reich was bleeding the jagdgeschwaders white.

The air war mingled physical discomfort and boredom with searing moments of sudden violence. Here, an 88mm flak hit has ripped a Fifteenth Air Force B-24 in half.

Big Week ended after the missions on the twenty-fifth. The Fifteen and Eighth Air Forces had flown a combined 3,823 bomber sorties while the RAF put 2,351 over Germany at night. Together, the Allies dropped 18,291 tons of bombs on eighteen aircraft factories and two ball bearings plants. The week cost the Luftwaffe at least a hundred pilots and almost three hundred interceptors. The USAAF lost 227 bombers; the RAF lost another 157. Some five thousand RAF and USAAF airmen died, returned to England or Italy wounded, or simply went missing over the flak-filled German skies.

Big Week inflicted significant damage on the targeted German factories. The Regensburg Bf-109 plant was totally destroyed, which effectively denied the Luftwaffe about 750 fighters. At Augsburg, 160 freshly completed aircraft were either destroyed or damaged in the bombing, and further production did not resume for over two weeks.

The factories weren’t the real targets though; the Luftwaffe was. And in meeting the American maximum effort with one of their own, the defenders of the Reich had been stretched beyond their endurance. The Americans finally had the Luftwaffe on the ropes. Now, they needed to deliver the knock-out blow.

They didn’t make it quite home. The end of a battle-damaged B-24 and its crew of ten dedicated young Americans.

A 91st Bomb Group Flying Fort over the Messerschmitt plant at Augsburg, Germany, during Big Week on February 25, 1944.