A graphic display of the P-51’s ruggedness at the 364th Fighter Group’s home station in East Anglia.

“I would rather have a mass of aircraft standing around unable to fly owing to a lack of petrol than not have any at all.”

—Herman Goering

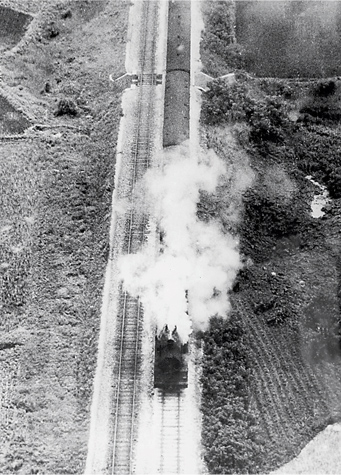

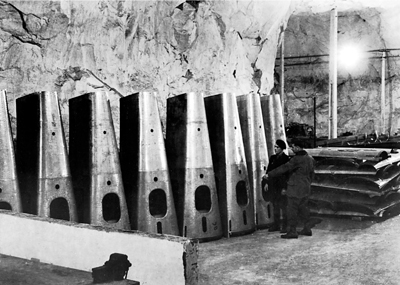

LIKE WINGED PARTISANS, THE VIII FIGHTER COMMAND STRUCK. Mustangs and Thunderbolts, cut loose from bomber apron strings, roamed low across Nazi-held Europe in search of anything worth blowing up. Trucks, staff cars, ammunition dumps, airfields, flak batteries, and trains became choice targets. Trains served as bullet magnet. If they moved in daylight anywhere in Western Europe that spring of 1944, chances were good an Allied fighter would drop down out of the clouds and rake it with gunfire. The pilots especially loved to blow up the locomotives. Fifty-caliber rounds could do a lot of damage very quickly, and a stricken locomotive would erupt in clouds of white steam when hit.

Ace Max Lamb, an original member of the 354th “Pioneer Mustangs,” found a train running along an open stretch of flat farmland. He led a flight of four P-51s down to flay the locomotive with machine gun fire. When it exploded, hundreds of Wehrmacht soldiers poured out of the now-stationary passenger cars. Line abreast, almost wing-to-wing, the four Mustangs made pass after pass at the soldiers, their sixteen M2 fifties slaughtering dozens in with every run. Caught without any cover, the soldiers panicked and either ran for it or lay flat and prayed. By the time the last spent casing fell from Lamb’s wing, the better part of a battalion had been mauled by four American pilots.

Max Lamb’s North American ride. Gentle and soft-spoken, Lamb was a capable and dedicated pilot who finished the war with 7.5 confirmed kills.

Welcome to the new air war, where fighter-bombers ruled the wild blue and nothing below was safe. With two months left to go before D-Day, Doolittle unleashed Kepner’s fighters and told them to wreak havoc on anything worth a bullet. At first, this applied only to VIII Fighter Command units that had completed their escort duties for the day. En route home from England, the pilots were told to fly low and go hunting. Starting in April this tactic evolved into specific missions. Using Ultra and other intelligence sources, the Eighth pinpointed the location of many Luftwaffe units based in France and Germany. On April 5, the VIII Fighter Command targeted some of those airfields. Bad weather hampered the operation, but two groups found their way to their targets and destroyed ninety-eight aircraft on the ground or in the air.

Once the VIII Fighter Command was unleashed from rigid bomber escort tactics, the Luftwaffe had no safe place.

Strafing trains became serious sport for the pilots of VIII Fighter Command. Destroying locomotives and rolling stock helped cripple the Wehrmacht’s strategic mobility and made it very difficult for the Germans to push reinforcements into Normandy.

The RAF’s Spitfires from the 2nd Tactical Air Force joined in the strafing and ground attack campaign throughout northwest Europe. During the Normandy campaign, a Spitfire caught Field Marshall Erwin Rommel’s staff car on a narrow French lane, strafed it, and wounded the legendary German panzer leader.

None of this would have been possible if the Luftwaffe still owned the airspace over the Continent. Big Week and Berlin set the conditions for this new offensive. And in concert with the fighter-bomber attacks, the RAF’s heavies, the Allied tactical air forces and Spaatz’s command worked on the pre-invasion “Transportation Plan.” Harris thought it was a useless diversion and wanted to keep his men focused on turning German cities into rubble. But the battlefield preparation for D-Day was truly massive in scope and required every aircraft to carry out.

A Polish-flown Spitfire airborne over England. The Poles never lost their extreme aggressiveness and took to the strafing campaign with singular fury.

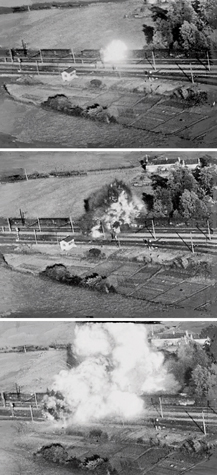

A 78th Fighter Group P-47D razorback Thunderbolt. Though designed as a high-altitude fighter, the Jug’s incredible ruggedness, ordnance capacity, and tremendous firepower transformed it into the best fighter-bomber of World War II.

Don Gentile’s famous Shangri-La, one of the best-known Mustangs of the European air war. He would run afoul of his commanding officer, Don Blakeslee, for flathatting (flying very low to the ground) in this aircraft for some reporters in spring 1944.

While stunting for his crowd of media types, Gentile crashed his Mustang and wrecked it. Blakeslee was so furious that he grounded Gentile and sent him home, ending his combat career.

The Transportation Plan called for sealing off the Normandy area from the rest of Europe by destroying the rail and road network in Western Europe. By knocking out bridges, destroying railroad yards, carpet bombing road intersections, and strafing trains and vehicles, the Allies hoped to prevent the Germans from quickly reinforcing their units in Normandy. Since the Wehrmacht had a larger force available than what the Allies could land and sustain on the Continent, the only way the invasion could succeed was if the Germans could not get more men and supplies to the new front.

Through April the Allied strategic forces split their effort between long-range strikes into Germany and supporting the transportation plan. Meanwhile, the Eighth Air Force’s Mustangs, Lightnings, and Thunderbolts continued their depredations all the way into southern Germany.

Part of the air plan in support of the Normandy operation called for the destruction of France’s road and rail infrastructure leading to the future battlefield. Here, a bridge over the Seine River has been dropped by a well-executed strike.

With drop tanks, all things were possible. With enough gas to fly almost anywhere in the Third Reich, the Luftwaffe lost its ability to find sanctuary from the Mighty Eighth’s roaming fighters. Even training units were caught and thrashed by the Mustangs, Thunderbolts, and Lightnings.

Preparing for another long-range mission over Germany.

By month’s end, the Germans knocked down 409 Eighth Air Force bombers, more than any other month. In the fall of 1943, such losses would have crippled the American campaign. But two seasons later, the USAAF’s build-up and replacement rate was so robust that the Eighth continued to grow even as it lost four thousand men in a four week span.

Though the Luftwaffe scored high in April, it was a Pyrrhic victory. The month’s dogfights killed or wounded 489 pilots. The defenders of the Reich proper suffered a 38-percent attrition rate. What’s more, the Luftwaffe’s training command only graduated 376 cadets that month. Most of these aviators possessed only half the flight hours of their grass-green Allied enemies. As the intensity of the air campaign escalated, such neophytes thrown in half-prepared were little more than airborne cannon fodder.

To avoid friendly fire incidents, the Allies painted their aircraft with white and black “invasion” stripes in the days before the Normandy landings. This was supposed to give the warships in the Channel and the ground troops on the beachhead a quick way to recognize Allied aircraft.

The Jug’s legendary ruggedness saved many pilots from death or captivity. Here, a 350th Fighter Group P-47 pilot brought his bird home after taking a hit in the oil system. Barely able to see through the viscous fluid sprayed all over his canopy, he nevertheless managed to get down safely.

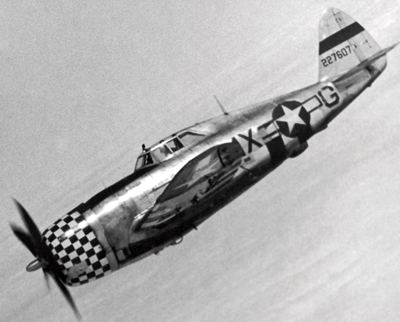

As the strategic bombing campaign demolished Germany’s aviation factories, the Third Reich began dispersing the industry into vast underground mines and facilities. Buried deep beneath the surface, these plants could not be destroyed by Allied bombs.

To build its newest-generation aircraft, the Nazis used slave laborers—Jews or Russians or Slavs rounded up to work under appalling conditions until they died.

Meanwhile, with a shortfall of almost a hundred warm bodies for his cockpits, Galland had to ask for more crews from the bomber and reconnaissance arms, thus weakening on the eve of D-Day the offensive striking power the Germans possessed.

In May, General Eisenhower released the strategic bombers from their pre-Normandy prep work. Spaatz took the opportunity to open a new offensive against Germany. This time, instead of going after Berlin or the aircraft industry, he selected the Reich’s oil producing infrastructure. The new effort began on May 12 when the Eighth hit seven synthetic oil plants with almost a thousand bombers. The Germans reacted fiercely, shooting down forty-six bombers while losing fifty-six interceptor pilots killed and wounded.

A German Gr. 21 rocket scores a near miss on a B-17. The Gr. 21s were most effective at dispersing a bomber squadron’s combat box. As the pilots banked and turned to evade the incoming weapons, the Luftwaffe fighters learned to pounce before the Americans could get back in formation.

Wrestling command of the air from the Luftwaffe did not come cheap.

A smoke pot marks the bomb release point for a formation of B-24 Liberators during a mission over France in June 1944. The days of individual bombardiers taking aim on a target were long gone and so was the illusion of pinpoint bombing.

Hermann Goering continued to lose credibility with Hitler as the Luftwaffe’s ability to perform its roles declined. In turn, he castigated his fighter leaders and questioned their bravery at a time when the front-line units were being pushed to the breaking point by the Allied air offensive.

Watchful eyes peer out from above the oxygen mask. Captain Oscar O’Neil, pilot and plane commander of a B-17 named Invasion II, personifies the veteran’s sense of vigilance in combat.

The bombing was not incredibly accurate, but one plant lost 17 percent of its production capacity. Albert Speer, Hitler’s Minister of Armaments, reacted to the Eighth Air Force’s raids with extreme alarm. He wrote Hitler, “The enemy has struck us at one of our weakest points. If they persist . . . we will soon no longer have any fuel production worth mentioning.”

The gravity of the situation forced the Germans to redeploy their anti-aircraft defenses to better protect the oil industry. By the fall of 1944, over a thousand AA guns protected key installations. These were not facilities that could be moved underground. Since the beginning of the year, the Germans had been busy establishing critical factories in mines and gigantic underground complexes to make them impervious to bombing. Much of the aircraft industry had been reorganized this way, and slave laborers from concentration camps were used on the production lines. In this way, Speer was able to drastically increase the outflow of armaments and aircraft despite all the damage the Allied air forces were doing to Germany’s cities.

For two years, the Americans and British had executed amphibious landings in both the Pacific and Mediterranean theaters. The hard-won lessons learned from those earlier operations were absorbed and incorporated into Operation Overlord, the invasion of western France. The key in every instance: command of the air over the beaches.

American troops load up for D-Day in Southampton Harbor.

While Harris and some other strategic-minded air commanders believed the diversion of the heavies in support of the pre-invasion aerial operations over France was a wasteful diversion from the main mission of crushing Germany’s industries and morale, the fact was using the strategic forces saved the lives of countless soldiers and sailors who otherwise would have faced much more intense opposition. Scenes like this sinking LCI would have been far more common had the Luftwaffe been able to strike the beachhead in numbers.

The final softening up aerial bombardment before the D-Day landings including Ninth Air Force B-26 Marauders hammering Utah Beach and the Eighth Air Force pounding targets behind Omaha Beach.

The crucial moments: Vulnerable LCVPs like this one churn for the Normandy shore, June 6, 1944.

A formation of Liberators on their bomb run.

Oil turned out to be the Reich’s Achilles’ heel. Cracking plants and refineries could not be moved underground or hardened. The only thing the Germans could do was ring them with anti-aircraft guns and trust that the Luftwaffe could hinder the attacking bombers.

The Luftwaffe could not. At the end of the month, Spaatz hammered the oil targets again. This time using four hundred bombers, thirty-two of which went down, the accuracy was stunning. The attacks inflicted massive damage. Combined with several Fifteenth Air Force raids on Ploesti, Spaatz’s bombers cut German oil production in half by the end of May. Despite losing eighty-four B-17s and B-24s, plus almost 850 airmen, the Americans had scored the biggest victory yet in the strategic air war.

In the month before D-Day, with the transportation plan fully executed, the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces struck at oil targets all over Central and Eastern Europe. The Fifteenth concentrated on Ploesti. Long gone were the days where the USAAF dreamed of a single, knockout blow on that critical facility. Instead, a grim campaign between the American bombers and the Axis repair crews played out through the spring and summer of 1944. The Fifteenth struck Ploesti scores of times, inflicting massive damage. Yet, in the end production didn’t cease until the first Russian tanks rolled through the refineries later in 1944.

All day long on the 6th, the VIII Fighter Command flew missions in support of the amphibious landings. Here, a 361st Fighter Group P-51 gets the signal for take-off in the morning. Some of the VIII’s pilots flew three missions or more that day.

Hunted on the ground, chased until flamed in the air, the Luftwaffe’s once-vaunted strength ebbed away to a skeletal presence by the end of the summer of 1944.

Return of the 361st Fighter Group following a mission over Normandy. The fighters of the Mighty Eighth ensured the Germans paid in spades for moving troops, supplies, or vehicles in daylight toward the growing battle in western France.

As the Luftwaffe’s interceptors were swept from the skies, the Germans increasingly relied on anti-aircraft batteries for their nation’s defense. It was a rare day over Germany when a bomb group could return without anti-aircraft artillery damage to its aircraft.

The destruction of Germany’s above-ground military industries continued through the summer, even after the shift to oil targets took place. Here, a thoroughly bombed Panther tank factory is examined after the war by curious GIs.

The German war machine felt the new campaign’s effects immediately. Calls went out to every command to conserve fuel and oil. Ruthless economy measures were put in place. The training of new pilots suffered as less aviation gas was made available. That meant the cadets received fewer hours in the air before being flung against the bomber streams. Worse things would soon follow as the campaign gained momentum.

May saw the first decline in American heavy bomber losses since the daylight strategic campaign began almost two years before. Not only did the USAAF have more Forts and Liberators available than any other time, the Luftwaffe had been ground down so severely by the attritional warfare over the Reich that its fighter units were staffed now by an increasingly small number of old hands surrounded by half-trained replacements. Since March, the battles over Germany had cost the Reich defense units no fewer than twenty-eight aces killed in action. Others, like Gunther Rall, suffered wounds that would keep them out of the fight for weeks and months to come.

As the Allied armies advanced into France, they came across some curious sights. Here in this ruined hangar the troops discovered a captured 100th Bomb Group B-17 Flying Fortress.

A 305th Bomb Group B-17 burns after crash-landing in France. The Allied advance in Western Europe afforded the Eighth Air Force new emergency airfields to use in case of battle damage. Thousands of airmen owed their lives to the front’s eastward shift that summer and fall.

A Fort crew prepares for a crash-landing.

By the summer of 1944, the B-17 ruled supreme in Germany’s daylight skies.

The Luftwaffe started the year with 2,395 single-engine fighter pilots. By June 1, 1944, the jagdgeschwaders had lost 2,262 of those pilots. In six months, the Luftwaffe suffered almost 100 percent losses. No organization can survive such a body blow. That the survivors continued to intercept raids and at times inflict heavy casualties stands as a testament to the courage and dedication in the face of an increasingly obvious lost cause.

In June, the Allied heavy bombers worked in concert with the rest of the D-Day invasion force to pummel the Germans in their coastal emplacements. After two weeks of that, Spaatz returned to the oil industry targets and began crossing them off a list that totaled slightly under a hundred facilities. In between raids, Bomber Command and the Eighth were both used as battlefield sledgehammers in Normandy in hopes of breaking the deadlock there. The Eighth nearly destroyed the elite Panzer Lehr Division around St. Lo in a carpet bombing attack that also inflicted almost five hundred friendly casualties on forward American units.

Despite the commitments in Normandy, Spaatz’s raids on the oil targets continued. By now, the Germans were experts in on-the-fly fix-it industrial repair. Workers swarmed over these critical facilities and soon restored much of the lost production. This time, Spaatz gave them no respite. Gone were the days of the single knock-out blow. The Americans had come up their learning curve and understood to win this campaign would require tenacity, patience, and consistency. By the end of July, the Eighth and Fifteenth smothered the aviation fuel facilities with hundreds of tons of bombs, reducing output by 98 percent. Speer’s apocalyptic vision of what lay ahead for the Reich had come true.