A V-1 plunges into a crowded London neighborhood.

“The superstition of the wonder weapon struck me as a transparent trick.”

—Johannes Steinhoff, In Letzter Stunde

THEY WERE SUPPOSED TO SAVE THE THIRD REICH: new technologies that seemingly came straight off the pages of pulp magazines and comic books. Rockets, guided missiles and jet fighters—the Germans raced the clock in a frantic effort to field these new “wonder weapons” that Hitler hoped would turn the tide of the war.

Offensively, the new weapons included the V-1 “Buzz Bomb” and the V-2 rocket. Both were used against London, Antwerp, and targets in Southern England. The V-1 became the world’s first operational cruise missile on June 13, 1944, when the Germans fired an initial volley at Southern England from facilities in France and Holland. With a 1,870-pound warhead, the V-1 could fly about 250 miles at 400 miles an hour.

Using a primitive autopilot system linked to a vane anemometer, the V-1 would fly in the general direction of its target. Once it traveled the distance between its launch ramp back and its intended destination, it would automatically enter a steep dive and explode on impact with the ground.

From June until the end of the war, the Germans launched about 9,500 “Doodle Bugs” at Allied targets. Only a quarter of those made it anywhere near their destination. Barrage balloons, anti-aircraft defenses, and fighters accounted for thousands of them. The others strayed off course or crashed. Still, the relatively small number that did reach their targets did considerable damage. By war’s end, the V-1 menace had killed or wounded over twenty-one thousand civilians.

The last German terror campaign used weapons straight from the pulp comic books of the era. The V-1 pilotless “buzz bomb” was the first of these new devices designed to kill civilians indiscriminately from remote locations hundreds of miles away.

A British Tempest chases a V-1 across the English countryside.

The V-2 proved to be a much more menacing and dangerous weapon. The world’s first ballistic missile, the V-2 actually entered sub-orbital flight on its trajectory to its target area. First launched against England on September 8, 1944, the V-2 alarmed Churchill and the rest of his cabinet. It flew too fast to be detected, prepared against, or shot down. In fact, most of the time it would impact and explode before anyone had heard it.

The launch pads could not be bombed, either, as the V-1s could. The V-2 could be carted around by trucks and fired from almost anywhere. Trying to knock out their facilities would simply not work. There were no defenses for such a weapon—that would have to wait decades until the advent of anti-ballistic missile systems.

The people of London and Antwerp would just have to endure. The mysterious explosions that rocked the British capital that fall were initially brushed off as gas leaks by the government, which sought to avoid a panic over the new weapon wielded against the civilian population.

To produce the Reich’s “wonder weapons” required setting up underground factories that could not be destroyed by Allied bombs. Here, GIs check out a V-1 production line in an underground facility after the war.

The dreaded V-2, the world’s first operational ballistic missile. The Allies possessed no defense to such a weapon and had to rely on counterintelligence tricks to fool the Germans as to the accuracy and lethality of their new weapon. This one was photographed in the United States after the war during a testing operation.

V-2 strikes inflicted about three thousand casualties and scored some horrifying hits on crowded locations. In Antwerp, 537 people died when a V-2 struck a movie theater. Another one landed on a Woolworth’s in London, killing 108.

With no effective defense, the British resorted to trickery. The Germans had developed a radio beam guidance system that gave the V-2 effective accuracy. Using its intelligence network, the British fed the Germans false information that the V-2s were falling ten to twenty miles beyond London. The Germans fell for this completely, recalibrated their guidance system and after that most of the V-2s fell harmlessly into the Kent countryside.

The V-1 and V-2 programs absorbed enough German industrial resources and material to produce an estimated twenty-four thousand fighters. In the end, they achieved nothing more beyond senseless destruction and loss of civilian life. Yet, these two offensive vengeance weapons gave hope to the besieged German people, whose sufferings under Allied bombs sparked a desire for revenge. The V-1 and V-2 attacks satisfied that urge. In a real sense, the Nazi regime invested vast treasure and resources into these weapons to mollify the population and inspire continued support for the government and the war effort. In the end, the average V-2 strike killed two people. The payoff did not match the outlay.

Coinciding with this mini-blitz on London was the arrival of the Messerschmitt 262 in operational service. The world’s first jet aircraft to reach front line units, the Me-262 symbolized the Luftwaffe’s last, best hope to turn the tide in the skies over the Reich. After the war, so much misinformation and outright lies about the aircraft circulated in the memoirs of various Luftwaffe leaders that for decades the true nature of this revolutionary weapon has been clouded. Fortunately a new crop of historians, led by Manfred Boehme, have stripped away much of the myth.

A buzz bomb over the English Channel. The V-1 threat forced the Allies to devote fighter units to anti–buzz bomb defense. Shooting them down required speed and nerve. Sometimes, the pilots would actually fly alongside them and use a wing tip to flip the buzz bomb over, causing it to lose control and crash.

The Me-262’s genesis dates back to April 1939 when Messerschmitt produced the first plans for a twin-engined jet fighter. The following year, on November 1, 1940, Messerschmitt went to work on the new design, now dubbed “Project III.” The initial airframe rolled out of the factory in January 1941. Later that spring, the project’s engineers fitted a conventional piston engine to the aircraft’s nose and test flew it for the first time. After numerous modifications, the first pure jet version of the new aircraft took flight a year later in July 1942.

The Me-262 represented a quantum technological leap over existing aeronautical technology. Like all major leaps forward, the project encountered numerous problems, not the least of which were the unreliable BMW jet engines. By 1942, Germany faced a crushing shortage of strategic materials, which made producing the complex metal alloys that could withstand the super-heated environment within a jet engine feasible. Substitutes for such parts had to be found, and all had serious drawbacks. The BMW engines never fully matured and the Me-262 program switched to the Junkers Jumo 004. The change helped only slightly. The Junkers contained the same Achilles’ heel the BMW engines possessed and could only function for about a dozen flight hours before they needed replacement.

By the summer of 1944, the Luftwaffe’s fighter force was equipped with increasingly obsolescent aircraft like the Bf-109. Eclipsed by planes such as the Mustang, the Spitfire XIV, the Hawker Tempest, and other Allied aircraft, the already hopelessly outnumbered German fighter pilots no longer stood a chance in the skies over Europe in the aircraft available to them. Adolf Galland, Goering, and others pinned their slender hopes on the revolutionary new Me-262 jet fighter-bomber. A hundred miles an hour faster than the P-51, Galland saw it as the weapon that could wrest control of the air away from the Allies and save Germany’s cities from further destruction.

An American patrol comes across a Me-262 in Austria. German jet technology became one of the most sought-after prizes in the postwar. Both the Russians and the Americans scoured the remains of the Reich to locate those who conceived and tried to perfect the 262 and other “wonder weapons.”

The technical problems surrounding the engines delayed the Me-262’s development throughout its gestational phase. In 1943, Adolf Galland flew one of the prototypes and saw the future from its cockpit. He saw this aircraft as the solution to the growing Allied strategic bombing campaign. With a fighter arm equipped with Me-262s, he believed the Luftwaffe could sweep the skies clear of Allied planes. He pushed for its immediate introduction.

That couldn’t happen any time soon. Teething troubles continued to plague the Me-262 and its engines. Messerschmitt announced in June 1943 that January 1944 would be the earliest it could deliver the first pre-production versions. Production would follow by the summer. Messerschmitt intended to construct 430 Me-262s a month by October 1944.

When the 262 showed up in the skies over Germany in the fall of 1944, the new fighter sent shock waves through the USAAF. Careful analysis of the jet’s performance helped mitigate its speed advantage. Mustang and Thunderbolt pilots learned that the 262 could not hope to maneuver with their more nimble fighters. The 262 was an energy fighter—fast passes and quick disengagements were the tactics needed for it to be successful. If a Messerschmitt pilot attempted air combat maneuvering, he would mostly likely end up going down in flames.

The 262’s engines could not be throttled up quickly, making them sluggish to accelerate. The Mustangs and Thunderbolts capitalized on that weakness by camping over airfields used by 262s and picking them off at their most vulnerable moments, as the jets began to take off or came in to land.

In the war’s final weeks, a two-seat night fighter version of the Me-262 began arriving from Messerschmitt’s underground production lines. It could have been a very effective addition to the nacht jaeger units, but it did not reach operational service in numbers. Besides, the ground war was all but over.

Walter Nowotny, one of Germany’s leading aces, took command of one of the first 262 fighter units. He led it into combat and was killed while fighting the Eighth Air Force in one of the new jets.

After the war, bitter Luftwaffe leaders like Adolf Galland sought to present the 262 as a potential tide-turning weapon that could have resulted in a German victory. But political bungling on Hitler’s part doomed the 262 and caused so many delays that it didn’t reach operational service until too late. Pure fiction. The 262 program was fraught with technological and material issues that took time to overcome. Even when it did reach operational status, the 262 represented immature technology that presented many very serious problems and limited its effectiveness in combat.

After the war, Adolf Galland, Albert Speer, and other senior leaders within the Luftwaffe and Third Reich claimed that Hitler repeatedly intervened in the Me-262 in such a chaotic manner that he delayed its introduction by months, if not years. They found a perfect scapegoat for the Luftwaffe’s defeat: a globally reviled dead madman whom nobody would ever defend. As a result, the early postwar literature is colored with this blame-laying and legend-spinning.

The legend goes like this: Hitler saw in the Me-262 its offensive potential and in 1943 ordered it to be produced as a bomber. That decision cost the program months as modifications were necessary to carry out the Fuehrer’s orders. Additionally, Galland claimed that Hitler ordered Messerschmitt not to prepare for full series production of the Me-262.

First, the Me-262 was designed to be a fighter-bomber virtually since its inception. Hanging a couple of bombs under the wings did not require the massive redesign the apologists have argued. And production was not hampered by Hitler’s decision-making, it was delayed by technical troubles, lack of engines and material, and the chaotic state of the Reich as a result of the strategic bombing campaign.

When attacking bomber formations, the Me-262 pilots generally attacked from astern and used rockets first before closing to cannon range. The four 30mm guns in the nose could tear apart a Fort or B-24 with just a handful of hits. Here, a B-24 goes down as two members of its crew free fall clear of it.

The Me-163 was a deadly aviation design Hail Mary—deadly for its pilots. A rocket fighter with only a few minutes’ fuel supply, it was supposed to engage the bomber stream, glide back to its airfield, and land on a centerline skid. In tests, landings often resulted in the Me-163 blowing up or, even worse. the fuel tanks rupturing and pouring toxic chemicals into the cockpit that would essentially melt the pilot.

With a top speed of over six hundred miles per hour, the Me-163 was all but impossible to intercept for a P-51 or Thunderbolt. However, once it burned through its small fuel load, the pilot now found himself in a modern air war at the controls of a glider. Within weeks of the end of the war, the 163 program was cancelled and the remaining pilots sent to Me-262 units.

German rocket and missile technology was far ahead of any Allied program. This weapon was the X-4, a wire-guided surface-to-air missile designed to be directed to a bomber stream where its proximity fuse would detonate its warhead. It did not see operational service, but could have been a deadly effective weapon.

The fact that the first Me-262s reached experimental units in the summer of 1944 was akin to a miracle, one that symbolized the remarkable capacity of the German aviation industry. Despite all manners of hardship, not the least of which most of Messerschmitt’s prewar factories burned to the ground in the wake of Allied bombing raids, the Me-262 reached operational status and made aviation history.

In July, nine Me-262 from Kommando Schenk moved to France to begin high-altitude bombing missions against the Allies in Normandy. Two months later, elements of KG-51 began to re-equip with the jet aircraft, though the numbers available remained paltry.

While a few Me-262 were diverted to the Luftwaffe’s bomber force, Kommando Hauptmann Werner Thierfelder had been preparing to take it into battle since December 1943. Once again, aircraft and engines served as the limiting factor. In the summer, Thierfelder died and Walter Nowotny took over the unit. It was renamed after him and sent into the fray to defend the Reich from American daylight bombers.

By fall, the situation for the Luftwaffe’s fighter force had grown beyond desperate. Half-trained pilots, thrown into the air in now-obsolescent aircraft like the Bf-109 died with grim rapidity. The average Luftwaffe fighter pilot died in combat after eight to thirty days of operational service. The last few remaining veteran leaders and aces attempted to hold things together as best they could, but the fresh-faced replacements they received possessed less than a hundred hours of total flying time. There wasn’t much they could do to save them. The learning curve in the skies over the Reich proved far too steep. Of the 107 Luftwaffe aces to score a hundred or more kills, only 8 of them joined fighter units after the summer of 1942. The rest were the old hands who formed the backbone of an increasingly brittle and green force.

While the wonder weapons received most of Goebbels’s ink, other firms, like Dornier, went to work on making the most out of existing technology. The Dornier-335 Arrow was the product of this design avenue. Powered by a pusher and tractor engine both, it possessed surprising speed and agility for such a large aircraft. Its two-seat version would have been a very capable night fighter. Very few were constructed during the chaotic final weeks of the war, and the program had no impact on the fighting.

The Luftwaffe’s leadership deluded itself believing that the Me-262 could change this dynamic and restore air superiority over the Third Reich. They pinned their hopes to the wrong star. Rushed into service, the Me-262 units suffered high casualty rates from operational accidents. The pilots were not well-trained on the revolutionary new aircraft. The engines failed and sometimes caught fire in flight. The operational attrition rate stayed high, and losses in combat with the USAAF ran to 15 percent. Late in the war, in one air battle, the Me-262 units suffered 56 percent casualties trying to defend the Reich.

For all these difficulties, the Me-262 certainly had potential. Though it could not accelerate quickly due to the nature of its engines, it possessed a top speed of almost 540 miles per hour—100 miles an hour quicker than the Spitfire or Mustang. Armed with four bomber-killing 30mm cannon plus twenty-four air-to-air rockets, The Me-262 solved the firepower problem that plagued the Bf-109 and Fw-190 geschwaders. Finally, the Luftwaffe could wield a bomber-destroyer that, unlike the Bf-110 or 410, could defend itself against fighter attacks thanks to its superior speed.

The Luftwaffe banked on it to save the day—and the night. The RAF continued its relentless destruction of Germany’s major cities. Casualties remained heavy, though the advent of Mosquito night fighters to escort the bombers helped keep the losses manageable. Aside from the Heinkel-219, the Germans did not have a night fighter anywhere near as fast and maneuverable as the Mossie.

Toward war’s end, a two-seat variant equipped with the latest “Stag Antler” airborne radar system began to roll off the production lines. Nachtgeschwader 1 received a few of these aircraft along with some standard single-seat Me-262s. For three months, they flew against the RAF and demonstrated the new jet’s dominance over the sleek and fast Mosquitoes.

The bomber kampfgeschwaders were to receive their own new jet attack aircraft in 1944–1945. This was the Arado-234. Faster than any Allied fighter, it could operate almost entirely free of threat of interception.

The advent of the jet fighter over Germany caused a ripple of panic in the USAAF that reached all the way back to Washington, D.C. Arnold, Spaatz, and Doolittle feared the Germans might actually be able to stop the combined bomber offensive if they could field enough Me-262s.

While the Allies kicked their own jet fighter programs into high gear, the front line P-51 and P-47 units devised tactics to counter the Me-262’s incredible speed advantage. The jet’s Achilles’ heel lay in its inability to accelerate quickly. The Americans picked up on this and concluded the best place to strike back at the jets—which the VIII Fighter Command pilots irreverently called “blowjobs”—was over their home airfields as they landed or took off. Down low and slow, the 262 was fresh meat for enterprising American pilots. When Me-262s hit an American formation, the escort fighters would immediately dispatch roving flights to all the nearby airdromes with concrete runways in hopes of catching the 262s in their most vulnerable moments.

The remains of a prototype space-age weapon known as the Gotha Go-229. This radical design presaged the American flying wing and B-2 Spirit programs by years. The project did not go far, but in concept the Go-229 would have been a tail-less, bat-shaped fighter-interceptor capable of speeds in excess of six hundred miles per hour.

As the Germans threw new technology into the fray, the Americans relied on the tried and true, first created in the 1930s. Here, an Eighth Air Force bombardier sits in the nose of his B-17G. The Norden sight was used to aim ordnance on German targets right until the final days of the war.

On October 7, 1944, Kommando Nowotny prepared to intercept 1,300 Eighth Air Force bombers en route to raid Germany’s oil infrastructure. Their home airfield at Achmer attracted the attention of a formation of 361st Fighter Group P-51s. Urban Drew spotted a couple of Me-262s on the runway. As they took off, he rolled into a dive from fifteen thousand feet and caught the trailing jet just after it tucked in its landing gear. With the 262 barely going two hundred miles per hour, Drew closed quickly and shot it out of the sky. The lead jet tried to get away by executing a climbing left turn, but Drew had energy and speed to burn after his 14,000 foot dive. He caught up to the other jet and raked it with .50-caliber bullets until it flipped over and augered into the ground.

Such attacks claimed the lives of several Kommando Nowotny pilots. On November 8, 1944, after his unit had been visited by several irate Luftwaffe generals who castigated the pilots for losing their fighting edge, Nowotny climbed into a 262 and set off to intercept an American B-24 formation.

Nowotny was one of the last “great” Luftwaffe aces. He held the Knight’s Cross and had been credited with 256 kills. Along with several other 262s from his unit, he struck the Liberator boxes outside of Achmer, shot one down and claimed a P-51. Moments later, he radioed back to base that he was on fire. His jet plummeted through a layer of clouds and cratered a few miles from his unit’s runway. The exact cause of his death cannot be established. He was either shot down by P-51s or he suffered one of the common and catastrophic engine fires so common to the immature technology embedded in the 262’s design.

A B-24’s waist gunner. Though technology and new designs affected the ebb and flow of the air campaign, at its roots the experience over Europe during World War II was a very human and tragic one.

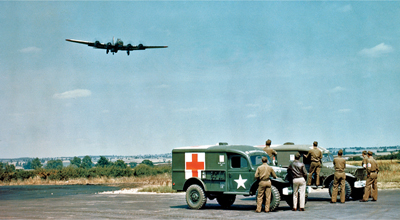

Limping home with wounded aboard, an Eighth Air Force B-17 fires distress flares on final approach so the ambulance and fire crews can rush to their assistance.

Planning for the day’s mission.

If the Me-262 was barely operationally ready in the fall of 1944, the Luftwaffe killed a lot of its own pilots by sending the Messerschmitt Me-163 “Komet” into battle. Designed as a short-ranged, rocket powered point defense fighter, the tiny Komet carried two 30mm cannons and could reach sustained speeds of over six hundred miles an hour. It was the fastest thing in the sky that year, and when its blowtorch was burning, no Allied fighter could touch it.

Yet, major drawbacks abounded. First, the rocket engine carried only enough fuel for about fifteen minutes of use. Canny Me-163 pilots would milk their fuel load by shutting the rocket off and gliding once they’d climbed above the bomber formation they had intercepted. Coasting along, they’d pick their target, restart the rocket and swoop down for a rear attack. Once they’d burned through their 120 cannon shells, they’d dive away and out of the fight. Then they’d glide back to their runway to make a landing on the narrow centerline skid.

Jagdgeschwader 400 flew the Me-163 in combat, claiming around a dozen kills while losing about the same number of aircraft operationally and in combat. Though the aircraft’s speed was unmatched and it could climb to 39,000 feet in an astonishing three minutes, the Komet failed as a bomber destroyer. The closure rate between an Me-163 and a B-17 was so great that the gunnery runs the Luftwaffe pilots could make lasted only a couple of seconds, even with a rear attack. The 30mm cannon was slow firing and had a low muzzle velocity, making it difficult for a 163 pilot to score a kill shot on a B-17 or B-24.

The fuel used to power the rocket engine was extremely caustic. In some instances, pilots returning after a flight would land hard on the skid and rupture one of the tanks, sending deadly chemicals into the Komet’s cockpit with gruesome results. As a result, the Me-163 drivers wore unique flight suits made of asbestos to prevent them from a horrible death.

The bomber crews were frequently overburdened with bulky flight suits and armor designed to protect them from the freezing temperatures and flak shrapnel. Moving around while in the air came with only great effort.

A bomb-ravaged Dornier factory rusts in postwar Germany, the remains of a Dornier-335 still sitting in the old production area.

In the final weeks of the war, the Luftwaffe recognized the Me-163’s failure and disbanded JG-400. Its surviving pilots joined Me-262 units and served out the war in the more effective, if still troubled, twin-engined jet.

The wonder weapons may have put a scare into the Allies in the final months of the war, but ultimately none of them had any effect on the Third Reich’s fate. In the air, the tiny number of Me-262s that rose to challenge the thousands of Allied bombers were simply brushed aside. As Spaatz’s men continued to hammer oil targets, the Reich all but ran out of fuel by the end of 1944.

Come winter, there were hardly any worthwhile urban targets left in Germany to bomb. The combined offensive had left the Reich in utter ruin, its people “dehoused,” their industries and neighborhoods destroyed. By early 1945, the bombs dropped during further area attacks just rearranged the rubble. In the war’s final months, Bomber Command dropped 181,000 tons of ordnance on Germany. So many bombs were expended that the factories back in England could not keep pace with the demand, and shortages plagued the RAF for the war’s final weeks.

Germany lay in ruins. Still its military and people fought on until the bitter end. And bitter it was. On February 13–14, 1945, Bomber Command sent aloft two waves of Mossies, Lancs, and Halifaxes, all bound for the picturesque city of Dresden, some 770 miles from England. The first wave carried 4,000-pound blockbuster bombs, designed to destroy water and sewer mains with their fearsome blasts, along with some two hundred thousand incendiaries.

Despite the arrival of the Me-262, the Mustang remained the dominate presence over Europe throughout 1944–1945.

Flying at 8,000 feet, the first wave of 250 Lancasters dropped all their ordnance on Dresden in under ten minutes. A firestorm took shape within the one-square-mile target area, sending flames so high that the second wave could see the city from sixty miles away.

The second wave was specifically intended to kill or incapacitate the rescue and fire crews fighting to save the city. Three hours after the first raid, the second one arrived and sowed even more destruction. Within minutes, the RAF bombers ravaged the city with another 1,800 tons of bombs.

The firestorm sent smoke up 15,000 feet. Temperatures reached 1,800 degrees. The civilians caught in the inferno were burned alive or died of smoke inhalation or asphyxiation when the firestorm sucked the oxygen out of their shelters. Others tried to flee the growing conflagration, but the flames sucked the air right out of the streets as well. Those who could not get away fast enough would suddenly fall unconscious, victims of anoxia. Seconds later, the flames would burn them to ashes.

The next morning, four hundred Flying Forts from the Eighth Air Force’s First Bomb Division struck Dresden as the dazed survivors dug themselves out of the rubble. The Eighth returned on February 15 to rearrange the rubble. Fires still blazed everywhere, and the dead lay untended in the firestorm’s wake. Somewhere between twenty-one thousand and forty thousand people died during these attacks. Over six thousand were cremated in one of the city squares, a testament to the desperate nature of the post-attack circumstances. Rescue and clean-up crews stumbled across so many bodies partially burned in shelters that eventually they gave up trying to extricate them. Instead, they cremated them in place with flamethrowers.

Seventy-eight thousand buildings lay destroyed, including most of Dresden’s industrial plants. Since the war, Dresden’s military value and the importance of its factories to the Third Reich’s war machine have been questioned by succeeding generations of historians. Some have called the Dresden raids a war crime. Debate rages over it even today.

355th Fighter Group P-51s. By the end of 1944, almost all the Eighth Air Force units had converted to the Mustang. The notable exception was the 56th Fighter Group, which loved its Jugs.

A common sight in early 1945 were hundreds upon hundreds of B-17s, all in tight combat box formations, streaming across Germany to deal destruction to numerous targets a day.

The suffering of those on the ground whose cities were destroyed by Allied bombs cannot lightly be dismissed. The February raids on Dresden have continued to arouse moral repulsion and have sparked ethical debates on the entire concept of strategic bombing ever since.

Singling out one raid seems at best an intellectual exercise when the bombing campaign killed up to 650,000 German civilians during the war. The Royal Air Force’s area bombing attacks claimed two-thirds of those lives. Other cities—Rostock and Hamburg among them—suffered Dresden’s fate.

As the Luftwaffe ran out of fuel, replacement aircraft, and pilots, it became impossible for its fighter units to contest every raid. Instead, during the final weeks of the war, the jagdgruppen would husband their resources until they had enough planes and gasoline to put a substantial force aloft. While they sometimes could score isolated successes, the inexperienced Luftwaffe pilots fell in droves to their better-trained veteran opponents in the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces.

As the Soviet army advanced on Berlin, the bombing campaign wound down. The last RAF raid on Berlin took place on April 21–22, 1945. A few days later, Bomber Command flew its final major mission. This final raid took out an oil refinery in Norway. The Eighth Air Force ran out of targets at the end of April as well. After repeated fighter sweeps and ground attack missions destroyed almost a thousand German aircraft in the air and on the ground, the heavy bombers hit the Skoda Armaments complex in Czechoslovakia on April 25. After that, the Eighth stood down. Mission accomplished.

The Third Reich’s cities had been destroyed. Germany’s industrial base had been ground to dust. The Luftwaffe had first been shot out of the sky, then hunted to extinction on the ground. Around 90 percent of Germany’s single engine fighter pilots became casualties during the war. Those were Stalingrad odds.

In return, Bomber Command suffered a 76 percent casualty rate. A young British male had a better chance of survival in the trenches of the Western Front as an infantry officer than he did in the skies over Germany.

The Eighth Air Force lost 49,000 airmen out of 350,000 deployed to East Anglia during the war. Altogether, the combined air offensive had cost the Allies over 100,000 men.

Hardly had the ink dried on Germany’s surrender document when the second guessing began. Given all the destruction, all the deaths of airmen and civilians, was the strategic bombing worth the effort?

The shattered aftermath of the German war machine.

While historians have debated the morality of the bombing campaign as well as its effectiveness, nobody disputes that the early 1944 USAAF campaign dealt the crippling blows that ultimately defeated the Luftwaffe over its own home turf.