PAUL’S strategy during his two years and three months’ residence in Ephesus (Acts 19: 8–10) had two facets. He stayed in the city dedicating himself to the formation of the community and to maintaining contact with his other foundations. The church, however, had to be apostolic. Hence, he commissioned others to spread the gospel outside the urban area, following the pattern dictated by the Roman roads radiating out from the capital of Asia.1 As we have seen, some went north to Smyrna and Pergamum. Others took a road angling off to the north-east, and evangelized Philadelphia, Sardis, and Thyatira. Still others took the great common highway to the east and brought the gospel to Magnesia and Tralles.2 One went much further, into the Lycus valley on the fringes of the province of Asia. It was his homeland (Col. 4: 12).

The Roman road, which Epaphras followed, was constructed by Manius Aquillius, who was proconsul of Asia 129–126 BC. For the first 80 miles out of Ephesus it followed the north bank of the river Meander, which it crossed on a bridge at Antioch-on-the-Meander, and continued along the south bank until it was blocked by a tributary, the Lycus (modern Çürük-su), coming in from the south-east.3 Turning to stay on the west side of this considerable river, the road first reached Laodicea, and then Colossae (192 km. or 120 miles from Ephesus), after which there was a bifurcation. The road of Manius Aquillius swung south to the coast. The Cilician road curved to the north to the cities of Paul’s ‘first journey’ (Acts 13–14).4

The eye of anyone entering the valley from the west is caught by a dazzling blaze of white against the brown of the cliff across the river. For millennia, mineral-saturated hot water has poured down the slope gradually building up a deposit so that today it looks like ‘foaming cataracts frozen in the fall’.5 The phenomenon was known to Strabo, who noted the ingenious use the natives made of it, ‘the water of the hot springs so easily congeals and changes into stone that people conduct streams of it through ditches and thus make continuous stone fences’.6 Today the site has the entirely appropriate name of Pamukkale, ‘Cotton Castle’, but in the first century it was known as Hierapolis.

It would be most unusual if the unique properties of the waters had not attracted settlers to Hierapolis from remote antiquity, but it, and its neighbour Laodicea (6 miles away across the river) appear on the stage of history only in the Hellenistic period. The oldest documented town in the valley is Colossae, which is 11 miles upstream from Laodicea. The double ‘ss’ in its name is thought to be a relic of a pre-Greek language,7 and it is mentioned in the fifth century BC by Herodotus (7. 30) and Xenophon (Anabasis, 1.2.6) as a large and prosperous city.

The virtual monopoly that Colossae enjoyed in the exploitation of the natural resources of the valley came under threat in the third century BC, when Seleucid monarchs intervened to create new commercial centres. Antiochus I Soter (281–261 BC) raised Hierapolis to the status of a city,8 and his son Antiochus II Theos (261–246 BC) conferred the same favour on a settlement called Diospolis/Rhoas, whose name he changed to Laodicea to honour his wife.9 In 220 BC a certain Achaeus raised the standard of rebellion in Laodicea against Antiochus III the Great (233–187 BC).

The rising was abortive, but in order to guarantee that it could not happen again, Antiochus III, around 213 BC, settled 2,000 Jewish families from Babylon and its environs in Phrygia and Lydia.10 It would be most surprising if a significant number of these colonists did not end up in the Lycus valley.11 A century and a half later, the Jewish population was considerable. In 62 BC the district of which Laodicea was the capital had at least 11,000 adult male Jews.12 Some twenty years later, the authorities of Laodicea assured the Roman authorities that Jews would not be hindered in the practice of their religion.13 The presence of a Jewish community with its roots in Babylon, is crucial for an understanding of the problems that Paul and Epaphras had to confront.

Despite the seniority implicit in giving its name to a particular colour (see below), Colossae lacked certain advantages enjoyed by its younger rivals. Laodicea was the capital of the district. The courts of the proconsul of Asia might be infrequent, but its role as the financial and tax centre gave it a latent power, which proved attractive to those interested in policy and business.14 Inevitably leisure facilities would be better than elsewhere in the vicinity; gladiatorial shows are attested.15 Hierapolis no doubt enjoyed a share of this tourist market. The pleasures of natural hot baths were intensified by the medicinal properties of the waters and drew seekers of luxury and health from a wide area. The merely curious no doubt flocked to inspect the Plutonium, a cave whose poisonous vapours slew animals.16

The extent to which Colossae lost out in the prosperity stakes is graphically illustrated by the dearth of visible remains when compared with the extensive ruins of Laodicea and Hierapolis.17 It cannot even boast a famous name, whereas Hierapolis could claim the Stoic philosopher Epictetus (AD 55–135), and Laodicea the rhetorician Zeno, the bravery of whose son, Polemon, when the city was attacked by the Parthians in 40–39 BC, won him the kingdom of Cilicia Tracheia.18

The volcanic springs and underground rivers alerted Strabo to the unstable character of the land in the Lycus valley, ‘if any country is subject to earthquakes, Laodicea is’ (Geography 12. 8. 16). Many went unrecorded, but major earthquakes hit in the reign of Augustus,19 and again in AD 60, as Tacitus reports, ‘In the Asian province one of its famous cities, Laodicea, was destroyed by an earthquake in this year, and rebuilt from its own resources without any subvention from Rome.’20 No earthquake that devastated Laodicea would have spared its neighbours. The recovery of Hierapolis is guaranteed by the existence of a bishopric there at the beginning of the second century AD, headed by Papias.21 Colossae, on the contrary, sinks into oblivion.22

In their heyday these cities lived from wool. The Lycus valley was a vast pasture in which numerous flocks wandered. In this it was no different from much of Anatolia. Yet the inhabitants managed to carve out a unique niche in the textile market by the quality of their products. According to Strabo, ‘The country around Laodicea produces sheep that are excellent, not only for the softness of their wool, in which they surpass even the Milesian wool, but also for its raven-black colour, so that the Laodiceans derive splendid revenue from it, as do also the neighbouring Colossians from the colour which bears the same name’ (Geography 12. 8. 6; trans. Jones).

It would appear that the glossy black fleeces associated with Laodicea were natural. Certainly this is the interpretation of Vitrivius, for whom it was explained by the water of certain springs from which the sheep drank (De Architectura 8. 3. 14). Strabo’s failure to specify the precise colour associated with Colossae is remedied by Pliny, who tells us that colossinus is a purple resembling that of the cyclamen blossom (NH 21. 51; cf. 25. 114). That the unusual characteristics of the water of the region contributed to the distinctive colour is suggested by a note of Strabo apropos of a neighbouring city, ‘The water at Hierapolis is remarkably adapted also to the dying of wool, so that wool dyed with the roots [madder-root] rivals that dyed with the cossus [kermes-berries] or with the marine purple’ (Geography 13.4.14; trans. Jones).

When Paul marched across Asia Minor for the second time, his goal was Ephesus, and he did not attempt to found new communities.23 Where then did he meet Epaphras, a native of Colossae (Col. 4: 12)? The encounter could have taken place on the road. Paul would have been glad of a companion, a potential convert, whose presence enhanced his security. Or it might have been in Ephesus. But it could have been much further afield. The probability is that Epaphras was in some way associated with the export of textiles from the Lycus valley, and if Lydia from Thyatira was selling in Philippi (Acts 16: 14), it is not at all impossible that the superior product of the Lycus valley was being marketed by Epaphras in Macedonia or Achaia. This latter hypothesis, however, is not really plausible. If Epaphras had been commissioned by Paul in Greece to plant the gospel in his home valley when he returned, it is rather improbable that Paul would not have turned aside for a few days, after having visited the Galatians, in order to check on how things were going. If he did not do so (Col. 2: 1), it can only be because the churches in the Lycus valley did not yet exist.

Wherever they met, Epaphras was formed as a missionary by Paul in Ephesus, and he must have been typical of those whom Paul chose to fan out to found other churches. From personal experience in Asia Minor and Macedonia, Paul knew the difficulty of coming into a strange city in which he knew no one. He had to find work in a congenial situation which would permit him to preach. Where was he to begin? He must have recognized immediately how much easier his task became when he linked up with Prisca and Aquila in Corinth. They provided a base and a ready-made set of contacts. In any case, thereafter he built it into his missionary strategy. He left the couple in Ephesus in order to have everything in readiness for his return from Jerusalem,24 and later would send them to Rome to prepare for his arrival there.25 They now carried the burden of loneliness and alienation, but they were strengthened by the confidence that Paul would soon arrive to share the responsibility.

Paul could have demanded of others, and probably did, the sacrifices he demanded of Prisca and Aquila. There are always those willing to strike out into unknown territory. But would it not have been much more efficient to select as missionaries those who started with a built-in advantage? The prime candidates were the energetic and enterprising women and men, like Epaphras, who came to the capital of Asia on business. It did not matter whether they were acting as principals or agents, they returned home to a network of acquaintances rooted in long-standing family, social, and business contacts. They did not have to look for work. They were known and trusted. The respect they had earned guaranteed that there were always at least some sympathetic ears to hear their first stumbling sermons.

The freedom of Epaphras to make a trip to Ephesus in order to seek Paul’s advice when problems developed at Colossae suggests that he was in business on his own account. The alternative is to suppose that he converted his employer, who proved to be most sympathetic in terms of time off in order to permit Epaphras to discharge his duties as founder of the church. The hypothesis is not impossible, but it is more complicated, and even Paul did not take the Christianity of employers/owners for granted. The relationship of Philemon and Onesimus is a case in point.

The legal aspect of this dispute has already been dealt with.26 Here we must confront much simpler questions, which lead us into unexplored aspects of the evangelization of the Lycus valley. How did Onesimus, a pagan (Philem. 10), know of Paul’s influence on his master, and how did he know where to find Paul in far-away Ephesus? In the light of the preceding discussion, one is immediately inclined to consider Epaphras as the source of this information. In Philemon 19, however, Paul takes the pen from the hand of his secretary to guarantee the repayment of whatever damage Onesimus had caused, and underlines his creditworthiness by pointing out that Philemon is in the Apostle’s debt, ‘you owe yourself to me’.

The natural interpretation of this phrase is that Philemon had been converted by Paul personally, presumably in Ephesus.27 It would have been natural of him to speak to his household of the importance of Paul in his life. Acceptance of this interpretation, however, leads to unacceptable consequences. It means that Paul had sent two apostles to the Lycus valley, but gives the credit for the establishment of the churches of Colossae, Laodicea, and Hierapolis to only one, Epaphras (Col. 4: 13). Had Philemon made no contribution, Paul’s compliments in Philemon 6–7 appear as condemnation by faint praise. Would Paul have slighted Philemon just at the moment he wanted something from him? The difficulty of admitting that Paul would have acted so stupidly forces us to consider the possibility that, in writing Philemon 1 and 19, he was acting on the principle that masters are responsible for the actions of their agents. If those who command are liable for damages, they can also claim the credit for success. In other words, Philemon was converted by Epaphras as Paul’s agent.28

Philemon was followed into the faith by his wife Appia,29 and by Archippus (Philem. 1). Together they became the nucleus of a house-church (Philem. 2), which may have been the first of a number of such sub-units which together made up the ‘whole church’ of Colossae. The social status of Philemon can be deduced from his ownership of at least one slave; it is confirmed by his possession of a house large enough to contain a guest-room (Philem. 22). Had Paul impressed on Epaphras the strategy, which he himself was to employ so successfully at Corinth? It was important to recruit quickly one or two people who could provide a centre for the nascent community.30 Nympha may have played this role at Laodicea, where she became responsible for a house-church (Col. 4: 15). Philemon is called ‘fellow-worker’ and Archippus ‘fellow-soldier’ (cf. Phil. 2: 25). The implication that both were active in the development of Christianity in the Lycus valley is confirmed by Paul’s treatment of the former as ‘a partner’ (Philem. 17; cf. Phil. 1: 5) and by the words addressed to the latter in Colossians 4: 17, ‘see that you fulfil the ministry which you have received in the Lord’.

The curious form of this admonition—it is introduced by ‘Tell Archippus’—and the contrast with the complimentary epithet in Philemon 2, indicate that the status of Archippus had changed between the writing of Philemon and Colossians.31 What might have happened? One scenario which deals adequately with the data runs as follows. Onesimus had injured his master Philemon in a serious way. Epaphras sent Onesimus to Ephesus to beseech Paul’s mediation in the dispute with Philemon. Although not a Christian, Onesimus, like any of the servants, was fully aware of the composition of the little community that met in his master’s house. Once Onesimus had been baptized (Philem. 10; cf. 1 Cor. 4: 15), the significance of the active missionary role of Philemon and Archippus became evident to him. And he told Paul, who needed to flatter Philemon in order to win a favour from him. Paul had never written this sort of letter before, and it demanded serious reflection. Before the missive was finished, Epaphras arrived and was arrested by the Romans because of his official association with Paul. In addition to informing Paul about the false teaching that circulated at Colossae, he spoke sadly about Archippus. Given the gravity of the theological situation, it does not seem adequate to postulate merely that Archippus was somehow less active than hitherto. ‘Tell Archippus’ (Col. 4: 17) makes sense only if he had left the community and would not hear the letter when it was read publicly (Col. 4: 16). Had he become involved with the false teachers to the point that he no longer found the liturgy of the church satisfying? Only an affirmative answer explains the urgency of Colossians. If a leader of Archippus’ quality had been seduced by esoteric teaching, the danger for others in the community was very real. A response could not wait until Paul or Epaphras was released from prison.

No consensus exists regarding the authenticity of Colossians. The scholarly community is split down the middle. Those who affirm Pauline authorship, however, are rather more hesitant than those who deny it.32 None the less, the conclusions of the latter are not always as well founded as the force with which they are articulated would appear to indicate.

The stylistic argument, which has always been considered the most objective, must be set aside.33 Paul’s use of co-authors and secretaries precludes the establishment of a writing style exclusive to the Apostle against which letters can be measured.34 Equally, without evidence that it was a standard pseudepigraphic technique, the names and personal notices (Col. 1: 7–8; 2: 1; 4: 7–18) cannot be dismissed as an artificial attempt to give Colossians a place in Paul’s ministry. Those who maintain the inauthenticity of 2 Thessalonians and Ephesians find no reason to postulate such a requirement. If, as I have argued above,35 such personal references are taken seriously, then Colossians must be dated to the summer of AD 53, during Paul’s imprisonment at Ephesus. The critical questions, then, are: (1) are the differences between Colossians and the other letters written during this period as great as have been thought? (2) if so, can they be explained as due to the particular circumstances under which this letter was written?

Opponents of the authenticity of Colossians find justification for their position in its view of Paul’s apostolic office and of the value of his sufferings. The latter, we are told, are understood to have a vicarious value, and Paul is presented as the universal, unique apostle. Such inflation of his position is incompatible with his historical role, and thus points to the artificiality of Colossians.36

Universalistic language is certainly not lacking in Colossians, but when looked at closely, it does not confirm the interpretation forced upon it. The note that the gospel is bearing fruit and growing ‘in the whole world’ (Col. 1: 6) is a simple reflection on the success of the ministry to the Gentiles, and in no way implies that Paul alone was responsible. On the contrary, the intrinsic power of the word of God is an authentically Pauline theme (cf. 1 Thess. 1: 5; 2: 13). Later Paul speaks of ‘the gospel which you heard, which has been preached to every creature under heaven, and of which I Paul became a minister’ (Col. 1: 23). The lack of the definite article before ‘minister’ underlines that Paul is not the exclusive agent of propagation, and the hyperbole is precisely paralleled in the Apostle’s very first letter, both with respect to the past tense and to the universal extension, ‘your faith in God has gone forth everywhere’ (1 Thess. 1: 8). Finally, the sole implication of ‘teaching everyone in all wisdom that we may present everyone mature in Christ’ (Col. 1: 28) is that Paul’s message is for all without exception.

Colossians differs from the other Ephesian letters in that it is written to a church that Paul did not found. It would not have been written, as we have seen,37 had Epaphras been free to return to the Lycus valley after having consulted Paul in Ephesus. Only when he too landed in prison did it become imperative to devise another way of dealing with the situation. Apparently no competent emissary was available and that left a letter as the only option. Who was to write it? Epaphras was the obvious candidate, since the Colossians were his people, and his problem.38 Could he not say on paper what he planned to say verbally? Some in Paul’s entourage were less sanguine. To express oneself adequately in writing in circumstances where a false word could be disastrous demands a very special skill. Epaphras had given no evidence of this talent, which Paul had demonstrated in his letter to the Galatians. In any event Paul accepted the responsibility. Epaphras might then appear to be the obvious choice as co-author; he was the local expert. The same could be said of Apollos with respect to the developing situation in Corinth,39 but, as in the present case, Paul preferred to rely on Timothy.

Paul’s lack of personal involvement with the Christians in Colossae and his sense of the autonomy of the local church explains the universalism of the texts just discussed. On the formal level, he could and did point out that Epaphras had been acting as his agent (Col. 1: 7), but on a a more profound level, he felt the need to evoke the world-wide scope of his apostolic responsibility in order to justify his concern for the Colossians (Col. 1: 25). The context in which this must be understood is the Jerusalem agreement (Gal. 2: 9), which authorized all missionaries to go everywhere.40 In Paul’s mind this meant that he could not exempt himself from any effort that might draw people to Christ. In no way does it imply that he felt that everything had to be done under his aegis. He took it entirely for granted that other missionaries would work in parallel with him and made it a principle not to duplicate their efforts (Rom. 15: 20).

Paul’s interpretation of his sufferings in Colossians 1: 24 has caused much ink to be spilled. The NRSV reflects the common translation of this verse, ‘Now I am rejoicing in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am completing what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church.’ Questions immediately arise: was Christ’s sacrifice somehow imperfect? is the genitive ‘of Christ’ to be understood as subjective, as objective, as qualitative, etc.? how can Paul’s sufferings be added to those of someone else? is there a quota of sufferings that must be endured before the Parousia? The mind reels before the permutations and combinations of the possible answers, each of which has found an advocate.41

Such complications, however, arise only because the translation is faulty. The interpretation of the verse is greatly simplified if the order of the key Greek words is respected,42 and hyphens are added for clarification, ‘I am completing what is lacking in Christ’s-afflictions-in-my-flesh for the sake of his body.’ Paul is not speaking of the sufferings of Christ in themselves, but of his own sufferings, which in a certain sense are those of Christ. In a previous letter he had written, ‘I live now, not I, but Christ lives in me’ (Gal. 2: 20). Subsequently he would try to get the same idea across by writing ‘always carrying in the body the dying of Jesus’ (2 Cor. 4: 10). Paul did not need great insight to know that his pain would be prolonged, and he was fully aware of precisely how it benefited the church. His imprisonment dramatized his commitment to Christ, which both impressed pagans and fortified believers (Phil. 1: 13–14). Colossians 1: 24 is nothing more than a typically Pauline Christologization of this theme.

The intensification of Paul’s functional identification with Christ in Colossians can be seen as simply the logical consequence of the insight of Galatians 2: 20, but it was not Paul’s style to develop methodically the ramifications of an idea. There must have been something in the attitude of the Colossians towards Christ which stimulated his reflection.

The difference between the Christology of Colossians and that of the other letters is usually explained in one of two ways. Defenders of the authenticity of Colossians date it at the very end of Paul’s life in order to give enough time for such a radical development of his thought. Those who refuse the authenticity of Colossians find the difference so great as to make Pauline authorship inconceivable. A third approach, which does more justice to the data of the letter, has been espoused by C. K. Barrett, ‘It seems rather that the Colossians … had done their best to give Christ a prominent place in the realm of cosmic speculation. What they had not done, and the editor now proceeds to do, is to recognize his earthly activity.’43 In other words, the concern of Colossians is not to lift its readers into the cosmic sphere, but to ensure that they do not lose contact with the mundane. The Saviour must stand on terra firma. His disciples must not retreat into ascetic isolation.

As Barrett perceived, the clearest illustration of what is actually going on in the letter is found in Colossians 1: 15–20. Didactic hymns were part of the liturgy at Colossae (Col. 3: 16), and it is generally recognized that Paul is here quoting one of these hymns. Its precise extent and structure has been the subject of intense debate.44 This is not the place to enter into dialogue with the wide variety of views which have already been expressed. The justification of my position will emerge, I hope, from the coherence of what follows.

The original hymn was made up of two four-line strophes, which are identical in structure:

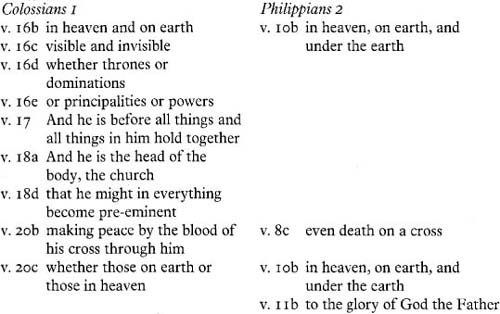

The repetition of key terms in the same order in each strophe reinforces the structure. The first two lines of each strophe are affirmations which are subsequently justified in the last two lines. Such perfection of balance betrays a deliberate creative effort. No artist who had invested so much would destroy the elegance of his work. The elements in the existent text which disturb the balance must have been added by a later hand, more concerned with content than with form. The same phenomenon was noted apropos of the hymn cited by Paul in Philippians 2: 6–11.45 Such similarity greatly reduces the subjective factor which is integral to every literary judgement. It is instructive to put the two sets of additions in parallel:

The similarities are so obvious as to hardly need pointing out. In both instances the redactor is concerned (1) to insist on the modality of the death of Christ, and (2) to restrict the meaning of ‘all things’ to intelligent beings. In the case of the Philippian hymn there is no doubt that the redactor was Paul; the authenticity of that letter is unquestioned. The language furnishes confirmation. If we leave aside the work of the evangelists, ‘cross’ and ‘to crucify’ are virtually exclusively Pauline terms in New Testament usage.46 This is all the more significant in that the traditional material, which Paul incorporates into his letters, mentions only the fact of the death of Christ without specifying its manner.47 The parallels create a prima facie case that the redactor of the Colossian hymn was also Paul. It is typical of him to emphasize the ‘blood’ of Christ (v. 20b).48 It is also characteristic of Paul to stress that Christ gained something by the resurrection (v. 18c).49

There is an obvious quantitative difference between the retouches of the two hymns. Those in Colossians 1: 15–20 are much more extensive than those in Philippians 2: 6–11. The natural inference is that the original Philippian hymn was closer to Paul’s theological perspective than the hymn which Epaphras brought from Colossae. This in turn opens the possibility that Paul retained the hymn for a specific purpose without accepting all its dimensions.

The distinction of two literary levels permits us to develop two readings, namely, the meaning of the original hymn, and the meaning Paul gave it by means of his additions.

The basic theme of the original hymn is obviously the mediation of Christ, first in creation and then in reconciliation. God is mentioned explicitly only as the referent of ‘image’, but he is certainly evoked by the passive verbs in verse 16a and 16 f, and possibly may be the subject of ‘was pleased’ (v. 19). The creative power of God is revealed in the action of his chosen instrument, and thereby Christ is exalted above all other beings.

In the first strophe there is no real difference between the formulae ‘in him’ and ‘through him’; the former can be instrumental, and is to balance ‘in him’ in the second strophe (v. 19) where, however, the meaning is different. On his first reading Paul may have understood ‘image of God’ in the light of his Adamic Christology based on Genesis 1: 27, but that would have quickly been corrected.50 The combination of ‘image’ with ‘first-born of all creation’ is more likely to have evoked the figure of Wisdom in the sapiential writings, notably Wisdom 7: 22–6; 8: 6; 9: 9. Paul after all was a child of the Hellenistic synagogue. The ambiguity of ‘first-born of all creation’ is remarkable: is he of or above creation? The emphasis on ‘all creation’ and ‘all things’ makes the cosmic dimension unambiguous. The participation of Christ in the act of creation extended to the totality of being. But in what sense? The context is of no help, no more than it is in answering the question arising from the one element which does not fit the sapiential background, namely, the presentation of all reality as directed, ‘to him’. What precisely does this mean? The failure of exegetes to reach a consensus on the answers to these questions suggests that obscurity was intended by the author(s).

In the second strophe ‘beginning’ again evokes Wisdom (Prov. 8: 22), but leaves vague the sense in which Christ vanquished death. The original author may have thought in terms of immortality, in keeping with the sapiential inspiration of his approach, but the formulation does not exclude resurrection. Christ’s being the first to experience life after death is due to a divine gift. The formula ‘to be pleased to dwell’ occurs regularly in the Old Testament with God as subject, e.g. ‘the mountain in which God was pleased to dwell’ (LXX Ps. 69: 17).51 Why the surrogate ‘Fullness’ should have been used here is unclear. Perhaps the author felt it would be more appropriate to the cosmic dimension of his theme, or feared that the Old Testament formula would be misunderstood. Those coming from a Jewish background would never have taken divine indwelling to mean that the person or place was divinized. A pantheist from Phrygia, however, would have gone away with a very different impression. Christ’s salvific mission is evoked only in the last line and by the verb ‘to reconcile’, which for the first time introduces a hint of tension within creation.

The hymn is a perfect example of what Paul calls ‘beguiling, persuasive speech’ (Col. 2: 4). Formal beauty clothes an abstract vision of Christ, which is allusive rather than explicit. The lapidary phrases are redolent of profundity, but yield no clear understanding. The pervasive ambivalence indicates that a univocal meaning was not intended. The hymn could be sung or recited by all believers (Col. 3: 16) in the belief that they were articulating a mystery beyond them. The initiated could debate the questions that still test the ingenuity of exegetes. In opposition to the hymn cited in Philippians 2: 6–11, nothing in the original hymn betrays Pauline roots. The preaching of Epaphras has been divested of realism by being transposed into a loftier and colder dimension.

The truth of the titles given to Christ meant that Paul could not reject the hymn out of hand. It evoked aspects of Christ that he would not have chosen to emphasize, but they were rooted in the revelation accorded to his people. To accept them was the price he had to pay for the lapidary formulae of the hymn which he realized he could turn against its originators.52

Before discussing this point, it is important to note the flexibility of Paul’s mind. He did not disdain to take over a key concept of the hymn. He had already used ‘fullness’ in the phrase ‘in the fullness of time’ (Gal. 4: 4). He now adopts the personal dimension of ‘Fullness’, and integrates it into his own thought. Later in the letter it appears in a formula where reality replaces mystification, ‘in Christ the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily’ (Col. 2: 9). By using the explicative genitive, ‘of deity’, Paul demonstrates that he understood correctly the role of the term in the hymn and removes any possible ambiguity. By the introduction of ‘bodily’ he directs the readers attention to the physical existence of him who is now the Risen Lord (cf. Col. 1: 22). Paul’s concern is to block any tendency to disassociate Jesus and Christ; ‘you received Christ (as) Jesus the Lord’ (Col. 2: 6).53 As in the original hymn, the presence of the verb ‘to dwell’ in 2: 9 means that Paul is thinking in terms of his Jewish formation,54 and the statement cannot be read as if it were the Pauline version of the prologue to John’s gospel.55

In his redactional additions Paul’s concerns are both negative and positive. He has to reduce the spirit world to its proper proportions and to replace Christ in his essential role.

By inserting 1: 16b–e, 20c Paul restricts the meaning of ‘all things’ to angelic and human beings. The prominence given to the angelic powers by listing their names is striking,56 and must be understood in the light of the reference to ‘the worship of angels’ (2: 18). The meaning of this cryptic phrase is disputed, but it seems most probable to understand it as Paul’s way of asserting that certain Colossians were being encouraged to give too much importance to visions of the throne of God surrounded by adoring angels.57 From Paul’s perspective such an invitation into a totally unattainable world compromised the primacy and centrality of Christ in the real world. Paul cleverly turned the tables on the teachers at Colossae, by using the creation dimension of their hymn to underline that, as the one responsible for the coming into being of the spirit powers, Christ was infinitely superior to them (Col. 2: 10).

The addition of ‘those on earth or in heaven’ to the last line of the second strophe (1: 20c) parallels that in 1: 16b (‘those in heaven or on earth’) but chiastically reverses the order, so that ‘those in heaven’ occupies the dramatic final place. Paul thereby again uses the original hymn to create a new argument against its writer(s). The need of human beings for reconciliation needs no emphasis, and the point is made several times during the letter (1: 21; 2: 13; 3: 7, 13b). Paul’s insertion, however, insinuates that the spiritual powers also need reconciliation.58 The angelic world, therefore, cannot be viewed uncritically. Wicked angels are unlikely to be satisfactory mediators between humanity and God. But how are terrestrial beings to judge their celestial counterparts? Paul does not need to make explicit the futility of the exercise. His rhetorical training had made him aware that conclusions are more convincing when drawn by the audience.

To the intellectual pleasure of seeing the Colossian teachers hoist with their own petard, Paul adds the satisfaction of directing their attention to the precise modality of Christ’s achievement by inserting the phrase, ‘making peace by the blood of his cross’ (1: 20b).59 The amendment evokes that of the Philippian hymn, ‘even death on a cross’ (Phil. 2: 8c), but the formulation is infinitely more dramatic. The graphic imagery will be intensified subsequently by the mention of ‘nailing’ (2: 14). Paul will never let anyone forget that redemption has been achieved within history through agonizing suffering. His choice of the verb ‘to make peace’ probably has less to do with any supposed animosity between heavenly beings, or between celestials and terrestrials, than with the tensions within the Colossian church. The letter contains evidence that the false teachers did not have it all their own way; ‘let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts’ (3: 15). Note also the letter’s emphasis on mutual forgiveness (3: 13), and on unity, ‘knit together in love’ (2: 2), ‘put on love which binds everything together in perfect harmony’ (3: 14).

The theme of unity also appears in the second part of each of the two-line insertion which Paul places between the strophes of the original hymn (1: 17–18a). The first part of each simply marks the supremacy of Christ. ‘AH things in him hold together’ is another matter. One has only to reflect on how this worked in practice in order to realize that Paul in verse 17 is parodying, not only the tone, but the enigmatic character of his source.60 This ability to find a verb whose ambivalence fits so perfectly into its context that very astute exegetes have taken it seriously once again reveals the quality of Paul’s education. What Paul really wants to convey is clearly expressed in the second line, where the unity of the church is defined as that of a ‘body’ (v. 18a). This is but the logical extension of the insight of Galatians, ‘you are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Gal. 3: 28). That Paul is here thinking along the same lines is clear from the extremely close parallel between this verse and Colossians 3: 11, which speaks of the new man ‘where there cannot be Greek and Jew, circumcized and uncircumcized, barbarian, Scythian, but Christ is all, and in all’.

The sources of Paul’s vision of the church as a ‘body’ have been long debated. The predominant view that he drew on Greek philosophical reflections on the body politic is also the most implausible.61 It is psychologically impossible that Paul should have taken over to describe the church a term used to characterize society. The latter appeared to him as riven by divisions (Gal. 3: 28; 5: 19–20), whereas the basic quality of the church was unity rooted in love (1 Thess. 4: 9). It is much more likely that he was jolted into thinking of the church as a ‘body’ by reflecting on the most memorable feature of the temples of Asclepius scattered throughout the eastern Mediterranean, namely, the ceramic representations of parts of the body which had been cured.62 The recommendation of Vitruvius that such temples be sited only in areas with clean air and pure water made them favourite places of recreation,63 and there is no reason to think that Paul did not frequent them on occasion. The sight of legs which were not legs, brought Paul to the realization that a leg was truly a leg only when part of a body. Believers, he inferred, were truly ‘alive’ only when they ‘belonged’ to Christ as his members (Col. 2: 6, 13; 3: 4). The ‘death’ of egocentric isolation has been replaced by the ‘life’ of shared existence.

When prolonged, this same line of thought gives us, ‘holding fast to the head, from whom the whole body, nourished and knit together through its joints and ligaments, grows with a growth that is from God’ (Col. 2: 19). This use of ‘head’ in the sense of ‘source’ is better attested than the alternative meaning ‘superior’, which is certainly the sense in Colossians 2: 10.64 The vision of the church as the Body of Christ also appears in later letters.65 It is not surprising that they do not take up the distinction of ‘head’ and ‘body’, which was dictated here by the theological climate of the Colossian church. In neither Corinth nor Rome was the supremacy of Christ questioned.

Paul’s insistence that Christ is present in him, and in all members of the Church draws the cosmic dimension of the Christological reflection of the Colossians down into ecclesiology. Paradoxically this point is further underlined by another specific feature of Colossians, namely, its identification of the gospel (1: 5, 23) as ‘the mystery’ (1: 26, 27; 2: 2; 4: 3), a theme that will appear later in 1 Corinthians 2: 6–9. This shift was no doubt inspired by the philosophical approach to religion that had become fashionable at Colossae (2: 4, 8, 18). There is no intention to exalt the gospel to a level that it did not previously enjoy. What Paul wants to get across is that ‘the mystery’ is no longer a mystery! The revelation which Jews and Gentiles struggled to find is no longer a secret. It has now been revealed by Christ and in Christ (1: 27; 2: 2; 4: 3). The riches of assured understanding, wisdom, and knowledge are achieved, not by contemplation of a heavenly, spirit-filled dream world, but by reflection on, and commitment to, Christ (2: 2–3). Sometime later Paul will express the same idea by presenting Christ as ‘the power of God and the wisdom of God’ (1 Cor. 1: 24).

Opponents of the authenticity of Colossians give great importance to its realized eschatology, which they claim is incompatible with the futurist eschatology characteristic of the genuine letters. A close reading, however, reveals that future statements predominate in Colosians. Christ is ‘the hope of glory’ (1: 27) because ‘when he appears, you will appear with him in glory’ (3: 4; cf. 1 Thess. 4: 17). There will be a final judgement (3: 6, 15–16), at which both the good and the bad will be assessed. The good will be presented holy and blameless, only if they continue in the faith (1: 22; cf. 1 Thess. 3: 13). It is within this clearly defined context that the two statements of realized eschatology—‘you were raised with him’ (2: 12); ‘if you have been raised with Christ’ (3: 1); ‘you died and your life is hidden with Christ in God’ (3: 3)—must be understood. Manifestly they cannot mean that the Colossians have already been physically raised from the dead. They are simply an alternative, and more vivid, expression of the body theme, ‘you who were dead God has made alive together with him’ (2: 13; cf. 3: 3). Grace has brought about a fundamental change. For Paul it was imperative to make sure that the Colossians understood that Christ had done everything essential. His plenitude meant that there was nothing that the spirit powers could add.66

In 1 Thessalonians 4: 1–12 Paul found it helpful to remind his converts that their life-style as Christians must be radically different from their previous comportment. In Colossians he does the same, but more explicitly, and at greater length (3: 1 to 4: 6). No doubt as his experience as a pastor increased, the generosity of his assumptions regarding human nature diminished. No longer did he take it for granted that his converts would be as whole-hearted as he had been in working out what behaviour was appropriate to life in Christ. In addition the situation at Colossae was complicated by the fact that some members of the church were attracted to excessive ritualism and ascetic rigour (2: 16–23), and looked down on others who did not share their views.

The insistence on Jewish observances—‘matters of food and drink, a festival, a new moon, or a sabbath’ (2: 16)—reveals that the situation at Colossae was analogous to that which obtained at Galatia, yet Paul’s reaction is completely different. Nowhere in Colossians does he evoke faith or the works of the Law. This has led some to disqualify him as the author of Colossians.67 They should rather have questioned just how similar the two situations were.

In Galatia, as we have seen, the churchs were troubled by intruders insisting that they had a mandate from the mother church in Antioch systematically to correct the gospel, which Paul had preached, by imposing full observance of the Law.68 It was a frontal attack on Paul personally, and on all that he believed. Nothing of the sort occurred in the Lycus valley. The churches there were not founded under the aegis of Antioch. There is not the slightest hint that Paul’s authority was questioned. There is no conclusive evidence that the false teachers were fellow-Christians, or that they were active proselytizers. Some believers may have been attracted to a form of esoteric Jewish teaching which circulated at Colossae and wanted to share their new insights with others. They did not reduce Christ to irrelevance as did the intruders in Galatia, but rather exalted his mediatory role. The problem with which Paul had to deal was not a doctrinaire attitude towards the Law, but the ascetic-mystical piety of Jewish apocalypticism,69 whose roots were more emotional than theological. In Galatia Paul had to counter a really serious threat, which was being pushed home as a matter of principle. At Colossae the issue was a fashionable fad, whose followers sought ‘heavenly ascents by means of various ascetic practices involving abstinence from eating and drinking, as well as careful observance of the Jewish festivals. These experiences of heavenly ascent climaxed in a vision of the throne and in worship offered by the angelic hosts surrounding it.’70 Jewish observances were important, not in themselves, but as the means to an end.

Given such differences, it would have been surprising to find Paul using at Colossae the tactics which had suited the situation in Galatia. There he had to demolish a thoroughly worked out vision of Christianity, whose coherent arguments were rooted in revelation. His opponents at Colossae, on the contrary, had no such intellectual depth. They described mysteries, apocalyptic visions, whose reality no one could verify. In contrast to the well-rooted epresentatives of Antioch, they floated in a fantasy world. Paul’s concern was to restore a sense of reality, to set the feet of the misguided on solid ground. They grasped at shadows; he had to show them that Christ was substance (2: 17). The most effective tactic was not to challenge the mystics head on, but to consistently introduce discreet modifications, whose cumulative impact would subvert their teaching completely. He relied on the sobering effect of the calm assumption of authority.

It is in this perspective that we must approach Paul’s use of a household code (3: 18 to 4: 1) which, if he were true to himself, he should never have employed. Nothing similar appears in any previous or subsequent letter of his. This series of paired injunctions (wives-husbands/children-parents/slaves-masters), not only represented the conventional morality of society, a social grouping that for Paul was the antithesis of the church, but it flatly contradicts the structure of the church ‘where there cannot be Greek and Jew, circumcised and uncircumcised, slave and freeman’ (3: 11). The use of the code here makes sense only as an invitation to the Colossians to leave the mystical realm of the angels and to return to the real world, where the fabric of daily life was woven from a multitude of interpersonal relations, of which the most basic were the three pairs listed here.

What is said to slaves stands out from the others both quantitatively and qualitatively (Col. 3: 22–5). Inevitably commentators have seen a relationship to the situation of Onesimus, who was returning to confront his injured master (Col. 4: 9). In that case, however, one would have expected either a warning to slaves not to imitate the dishonesty of Onesimus, or an expanded monition to owners on how slaves should be treated. Neither appears here. It might be thought that the directive was made necessary by agitation among Christian slaves at Colossae to be given the equality they theoretically enjoyed as members of the same Body, but the formulation militates against this interpretation.71

We are forced to conclude that Colossians 3: 22–25 reflects Paul’s habitual attitude towards slaves who accepted Christianity. Contrary to what one might have expected, he was not concerned with their liberation. Within the community he took it for granted that they would show and share the love that was its most distinctive feature, but there is no hint that he did anything to change the social order. This is well illustrated by the case of Onesimus. Paul’s request was that he should not be treated ‘as a slave’ when he returned to Colossae. There is no demand that he be manumitted (Philem. 16–17).72 When sometime later Paul was forced to confront the issue of slavery by the Corinthians, who believed that their relationship with God could be improved by a change in social status, he responded (a) that no change should be initiated for the sake of principle; (b) that a social change could be initiated to compensate for a human weakness; and (c) that a social change initiated by factors outside one’s control could be accepted (1 Cor. 7: 17–24).

In Colossians 3: 22–5 all Paul’s attention is focused on the authenticity of a slave’s life. Of the six relationships dealt with in the household code, only two were likely to be marked by deception. In many ways the position of children was parallel to that of slaves; they did not control their lives. The former, however, are minors, and it is a father’s duty not to create the conditions for deception. Even if ill-treated, slaves are adults, and responsible for their attitudes. What Paul does not want them to do is to obey orders to the letter, while the heart raged, and hate corroded the spirit. The reason behind this position can be deduced from Colossians 4: 5–6, where Paul stresses the witness value of the comportment of Christians (cf. 1 Thess. 4: 12). The internal tension, which was the occupational disease of slavery, had to be resolved in order to permit the transforming effect of grace become visible.73

While in prison in Ephesus Paul planned two visits as soon as he was released, one to Philippi (Phil. 1: 26; 2: 24) and the other to Colossae (Philem. 22). He did not make the visit to Philippi. It was still on his agenda in the early summer of AD 54 when he wrote 1 Corinthians 16: 5. Was the visit to Colossae also aborted?

Paul was probably released in the latter part of the summer of AD 53. We have seen that the likely reason why he did not go to Philippi was the situation in the church at Ephesus, where there was significant opposition to his leadership.74 The round trip would have taken the minimum of a month75 and brought him dangerously close to the moment when normal sea travel ceased. If ships no longer sailed from Neapolis, he would be trapped in Macedonia for the winter, with unacceptable consequences. A prolonged absence might guarantee the success of a different vision of Christianity at Ephesus. Moreover, to leave the city at that crucial moment might be interpreted as the flight of a coward.

These reflections do not militate with the same force against a visit to Colossae. Paul’s reason for going to Philippi was essentially for the pleasure of seeing believers who had always been loyal and co-operative. It was intended to refresh his spirit after a tense time under investigation. Apart from the tension generated by the personal competition of Euodia and Syntyche (Phil. 4: 2), there were no problems that imperatively demanded his presence. It would not have been difficult for Paul to rationalize his failure to keep his promise to the Philippians as the repudiation of a selfish decision made in a moment of weakness.

The planned visit to Colossae could not be avoided so easily. An important doctrinal point was at stake, and, Paul had accepted responsibility for the work of his agent, Epaphras, by writing letters to the Colossians and to the Laodiceans. He needed to know whether the way he had dealt with the false teachers had been successful. If not, it was imperative to make a further effort. Paul, however, did not have to go to Colossae himself. There were at least two other sources of information available. Tychicus was a permanent member of Paul’s entourage (2 Tim. 4: 12). Although it is not stated, it must be presumed Paul expected him to return to Ephesus with a report on the situation at Colossae.76 Epaphras would certainly have returned to Colossae the moment he was released, and could be back in Ephesus within two weeks, if the situation warranted it.

Paul must have wondered whether he should rely on second-hand information or go and see for himself? A decisive factor in his internal debate was his conviction of the autonomy of the local community. Whatever needed to be done as the result of his letter would have to be accomplished from within, as a member of the community. In many other churches this would mean no more than slipping back into the niche which he had occupied for a year or more. At Colossae he knew people only by reputation. He had met none of them personally (Col. 2: 1). To know them, and to be known by them, would take time. The more he thought about it, the more Paul became convinced that, if he went to the Lycus valley, he would be obliged to spend the winter there.

Could he afford so much time away from Ephesus? On balance Paul thought not. His personal position there was in danger, and it was the place which he had selected as his base for contacts with other churches. He had just had to deal with a problem in Corinth via the Previous Letter (1 Cor. 5: 9). Moreover, he had not formally promised the Colossians that he would visit them. Nothing about a visit is mentioned in Colossians and he did not plan to stay with Epaphras, the leader of the community, with whom he had shared a prison cell. The request for a guest-room was addressed to Philemon (Philem. 22), and could be considered a purely private matter. It would be more prudent, Paul decided, to wait for the reports of Tychicus and Epaphras.

What news they brought him we shall never know. From the following spring Paul was completely absorbed by the problems of the church in Corinth, and left Colossae to the care of Epaphras.