Thrust down into the industrial heartland of the United States, Ontario is a highly modernized region, but it is also a wilderness with 90 percent of its area under forest.

But it is a land, a country, a home. Underlying the exotic diversity of Ontario’s population is a common love of place, whether that place be a Gothic Revival farmhouse at Punkeydoodles Corners or a New Age zucchini plot on Toronto’s Markham Street. In 1844 J.R. Godley, a traveler from Great Britain, described Upper Canada as a place where “everybody is a foreigner and home in their mouths invariably means another country.” Today Ontario is still a land of many peoples, but its residents have found their home.

The Governor General’s Foot Guards during Changing of the Guard on Parliament Hill in downtown Ottawa.

iStock

The voyageurs’ heartlands

Although home to First Nations people for millennia, and a corridor for the fur trade, the living essence of modern Ontario isn’t found in the longhouse or canoe portage, but in the limestone homes of the United Empire Loyalists that stretch along the St Lawrence River.

More than any other region of Ontario, eastern Ontario remains devoted to the Loyalist traditions of “peace, order, and good government.” The stolid farmhouses, regal courthouses, and towering Anglican spires proclaim that no matter what the “democrats and levelers” in western Ontario may do, the East will be faithful to the province’s motto: “Loyal she began, loyal she remains.”

A blue jay in Ontario.

Dreamstime

There’s no more historically resonant place to begin a tour of Ontario than in the counties of Prescott-Russell and Glengarry, wedged between the Ottawa and St Lawrence rivers. The lower Ottawa countryside appears more Québécois than Upper Canadian. Barns boldly decked out in orange and green, silvery “ski-jump” roofs, and towns centered on massive parish churches reveal a distinct French-Canadian character.

But this is Ontario, not Québec. Surveyed by British army engineers, all of southern Ontario is rationally divided into little blocks (lots) within big blocks (townships) dissected by concession roads that irrationally ignore such non-Euclidian features as rocks, boulders, hills, lakes, and swamps.

A bagpipe band performs at the annual Glengarry Highland Games in Maxville.

Dreamstime

Driving southwest from the Ottawa River, the French place names give way to towns named Dunvegan, Lochiel, Maxville, and Alexandria, telltale signs that this is now Glengarry County. Glengarry was the first of the hundreds of Scottish settlements in Ontario.

Fact

At Dunvegan, near Maxville, one of Glengarry Museum’s prize exhibits is a cooking pot used by Bonnie Prince Charlie at Glengarry, Scotland, 1746.

Beginning with the arrival of the Loyalist Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment in 1783, the hill country north of the St Lawrence became the destination of thousands of emigrant Scots. Entire parishes from Glengarry, Scotland, emigrated for the promise of free land and the chance to escape the oppression of their landlords.

River of empire

At Cornwall, Ontario’s easternmost city, the Robert Saunders St Lawrence Generating Station stretches across the river to harness the thrust of the Great Lakes as they are funneled toward the Atlantic. Appropriately, an abstract mural by the artist Harold Town adorns the observation tower. For this is a triumph of the modern technological age over the defiant, age-old barrier of the Long Sault and International Rapids. With the opening of the St Lawrence Seaway in 1959, the interior of the continent was made accessible to the ocean-going giants and the St Lawrence superseded the Rhine as the world’s foremost river of commerce.

It is a river of empire. The French and English struggled for 150 years to determine control of the Great Lakes waterway, and when they were done the Canadians and Americans took up the cudgels. Indeed, it is a ripe irony typical of Canada that in order to remain British, the American Loyalists emigrated to share this river with the ancient enemy of the British Empire: Les Canadiens.

At Morrisburg, upriver from Cornwall, Upper Canada Village 1 [map] (early May to early Sept daily 9.30am–5pm; www.uppercanadavillage.com) presents a historical re-creation of what life was like for these loyalist immigrants. Early log cabins are juxtaposed with spacious American Classical Revival houses, illustrating the changing fortunes of the first political refugees to find a Canadian haven.

Iroquois legend tells of two potent spirits, one good, the other evil, who battled for control of the mighty St Lawrence. In their titanic struggle, huge boulders were tossed across the river in a great cannonade, many to fall short into the narrows leading into Lake Ontario. With the triumph of the good spirit, a magical blessing fell upon the land, bringing rich forests of yellow birch, red and white trillium, silver maple, and winged sumac to life upon the countless granite chunks scattered about the river. Today they are called the Thousand Islands 2 [map].

Tip

The best way to see Thousand Islands is by boat (good places to pick up a cruise include Gananoque and Rockport). These pink granite outcrops, some forested, are adorned by simple summer houses and opulent mansions.

The Power House of Boldt Castle in Thousand Islands.

Dreamstime

Brockville, 85km (53 miles) southwest of Cornwall, a stately Loyalist city with early architectural treasures along Courthouse Avenue, serves as the eastern gateway to the islands. Cruises around the numberless islands leave from nearby Rockport and Gananoque (“gan-an-ock-wee”), a more rambunctious resort town 53km (33 miles) closer to Kingston. The Thousand Islands have long been a playground for the very rich who, no matter how bad their taste in architecture, always seem to have an eye for the world’s most extraordinary real estate. The most famous of the millionaire “cottages” is an unfinished one named Boldt Castle 3 [map] (early May to mid-Oct daily from 10am; www.boldtcastle.com), which broods over Heart Island. As it is on American soil, visitors who are not American must bring proper identification, generally a passport.

Begun in 1898 by George Boldt, king of the Waldorf Astoria, it was never completed due to his grief over his wife’s death. Today it stands open to the elements and to the curious, and a major ongoing restoration continues on this piece of island history. A more lasting monument to Boldt is the Thousand Islands salad dressing that his chef concocted in honor of the region.

Kingston and the Rideau Canal

Briefly the capital of the United Provinces of Canada (1841–3), the city of Kingston 4 [map] has never quite recovered from Queen Victoria’s folly in naming Ottawa the new capital of the Dominion of Canada in 1857. Kingston certainly meets all the requirements of a capital city: a venerable history stretching back to 1673 and Fort Frontenac; a quiet dignity redolent in the weathered stone houses that line its streets; and a grandiose, neo-Classical City Hall, erected in 1843 in expectation of Kingston’s greater destiny. The Martello towers strategically placed around the town’s harbor and the great limestone bulwark of Fort Henry (mid-May to mid-Sept daily 10am–5pm; www.forthenry.com) are testimony to the enduring fear of invasion that the war of 1812 engendered.

Apparently, the spirit of 1812 lives on at Queen’s University, the pride of Kingston, founded as a Presbyterian seminary in 1841. In 1956 the student body invaded the nearby town of Watertown, New York, under cloak of night, replacing the “Stars and Stripes” flying at public buildings with Union flags.

Fact

Sir John Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, was a wily boozer. On vomiting once mid-speech he claimed that his opponent always made him feel ill.

The memory of Sir John A. Macdonald, the first prime minister of Canada, is as permanent a fixture in Kingston as any fort or college. Bellevue House (Canada Day–Labor Day daily 10am–5pm, Victoria Day–Canada Day and Labor Day–Thanksgiving Thu–Mon 10am–5pm), an Italianate villa occupied by Macdonald in the late 1840s, is now a museum filled with memorabilia of the Old Chieftain. More importantly, Macdonald’s unofficial political headquarters, the Grimason House (now the Royal Tavern), is still standing and open for business in the city center.

The Rideau Canal waterway and Parliament, Ottawa.

Ottawa Tourism

Just to the east of Kingston, between the harbor and old Fort Henry, lies the southern entrance of the Rideau Canal. Built between 1826 and 1832, the canal follows the path of the Rideau river route northeast through 47 locks, numerous lakes, and excavated channels until it emerges beside Parliament Hill (located in Ottawa) on the Ottawa river. Today the canal region is a pleasure-boat captain’s delight. Sleek-lined yachts and flat-bottomed cabin cruisers play snakes and ladders with the great stone locks, many of which are as they were over 150 years ago.

To the thousands of Irish laborers brought to Canada to construct the canal, the route was a foul, mosquito-ridden wilderness and their British Army taskmasters nothing less than Pharaoh’s satraps. Rapids were dammed, boulders blasted, and huge stone blocks hauled through roadless forests. The cost in human life was terrible. During construction in the 30km (18-mile) long Cranberry marsh, 1,000 workers succumbed to yellow fever.

The purpose of the canal was military, not economic. The British Army wanted a second, more secure route connecting Upper and Lower Canada in the event of an American seizure of the St Lawrence. The military character of the canal is evident at Merrickville, 48km (30 miles) southwest of Ottawa, where the largest of the 22 blockhouses that were built to protect the route still looms over the river.

Many of the canal’s laborers settled in the region. A bevy of Scottish master stonemasons, lured across the water to build the locks, stayed on to build the town of Perth on the Tay River, 41km (25 miles) west of Merrickville. Perth today is a feast of exquisite Georgian, Adamesque-Federalist, Regency, and Gothic residences – one of the most photogenic towns in Ontario.

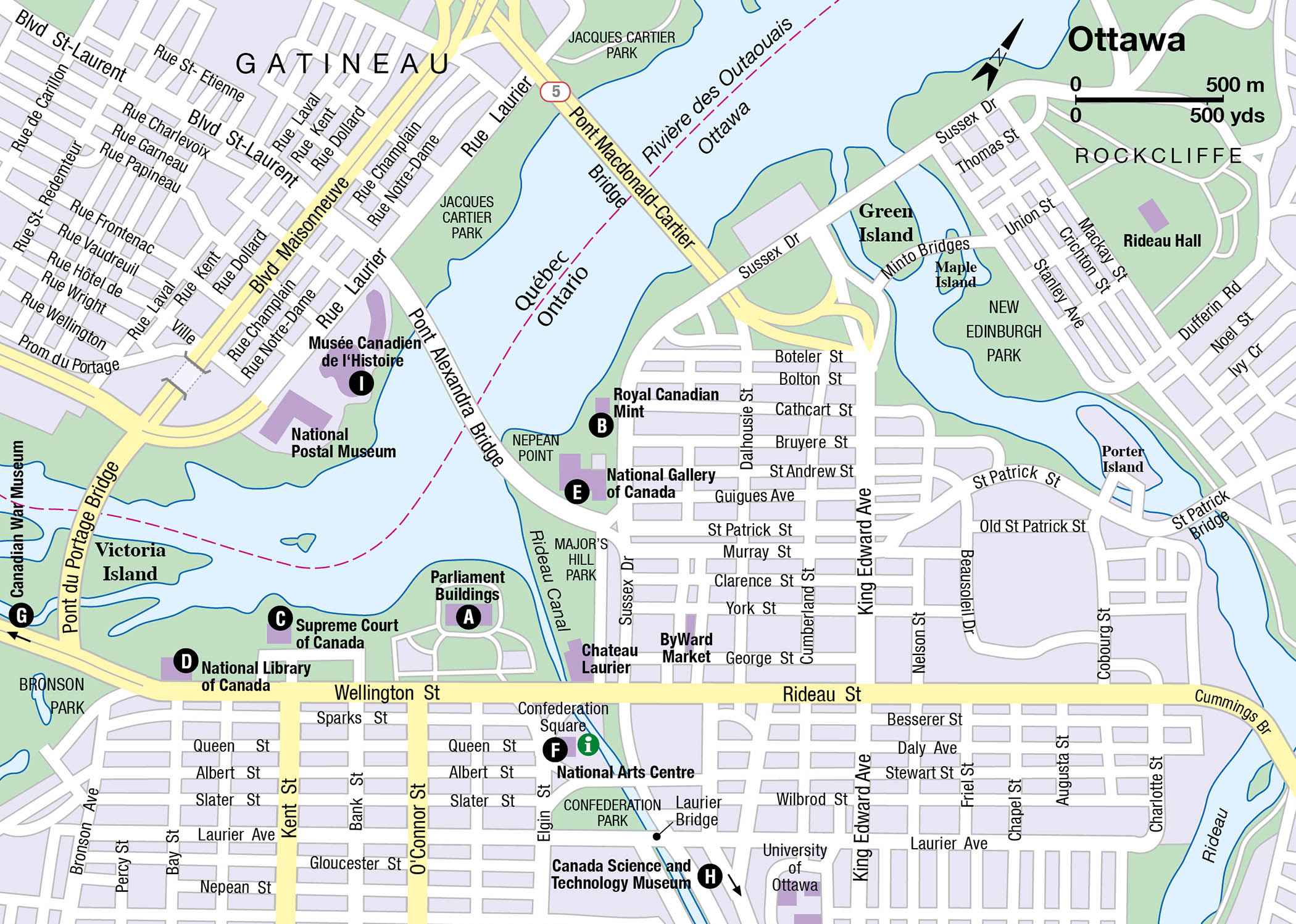

Ottawa

Queen Victoria’s choice of Bytown, then newly renamed Ottawa 5 [map], as her capital in the Canadas was greeted with shock by her trusting subjects. Today’s equivalent would be commanding all the capital’s administrators, pollsters, and politicos to pack up their bags and begin working in Tuktoyaktuk in the Northwest Territories.

The indignity wasn’t limited to just moving to a backwater; in the mid-1800s Bytown was also the most notorious work camp in North America. Lumber was king of the region and Bytown was its capital. Rival shantymen gangs the size of regiments set up shack towns here. Worked like machines, ill-fed, isolated, and racially divided, the lumbermen spent their recreational hours in drunken bouts of kick fights and eye gouging. It was in these muddy, dangerous streets that the Parliament Buildings A [map] (daily; tours, free; www.parl.gc.ca) were erected between 1859 and 1865, rather like the proverbial pearl in a pigsty.

The contrast between these savage shantymen and their descendants – well-ordered, conformist civil servants – is wonderfully absurd. It is the contrast between settlement and wilderness, between convention and epic adventure that runs through Canadian history. The contrast has not quite vanished from Ottawa today. In the Gatineau Hills (located in Québec) that rise up behind Ottawa to the east, wolf packs still gather to howl. And at the Royal Canadian Mint B [map] (daily 8am–8pm; www.mint.ca), Canada’s moneymakers still churn out coins depicting wild birds, moose, and beavers.

For Ottawa will never be a capital city in the style of Washington or Brasilia, fashioned around a grandiose design that reorders the world along geometric lines. Initiated in 1937, the Capital Region Plan of designer Jacques Greber emphasizes the area’s natural beauty and molds the city around it. Consequently, pleasure craft wend their way through the downtown center’s parks in summer, while winter turns the Rideau Canal into an ice-skating promenade. The annual gift of thousands of tulips by the Netherlands, in gratitude for Canada’s wartime hospitality to the Dutch Royal Family, makes spring in the city a visual delight.

Sculpture outside the National Gallery of Canada.

iStock

Because of its national stature, Ottawa is richly endowed with superb cultural resources, museums, and galleries. Besides the Parliament Buildings, the Art Deco Supreme Court of Canada C [map] (May–Aug daily 9am–5pm, guided tours; Labor Day–Apr Mon–Fri 9am–5pm, reservations required for guided tours; free), the National Library of Canada D [map], and the residences of prime ministers, governors general, and foreign ambassadors, Ottawa boasts the National Gallery of Canada E [map] (1–20 May and mid-Sept–end Sept daily 10am–5pm, Thu until 8pm, late May–mid-Sept daily 10am–5pm, Thu until 8pm, Oct–Apr Tue–Sun 10am–5pm, Thu until 8pm; www.gallery.ca), the country’s foremost gallery, made primarily out of glass; the National Arts Centre F [map], comprising opera house, theater, and studio, and home to the acclaimed National Arts Centre Orchestra; the Canadian War Museum G [map] (daily; free Thu 4–8pm; www.warmuseum.ca), which traces Canada’s wars or involvement in wars from the 17th century; and the Canada Science and Technology Museum H [map] (closed for renovation and expansion until fall 2017; www.cstmuseum.techno-science.ca), containing an impressive display of steam locomotives.

Fact

A lighthouse from Nova Scotia, the impressive locomotive hall, plenty of hands-on displays, and a vast refracting telescope attract visitors to Ottawa’s Science and Technology Museum.

Across the river in Gatineau (formerly Hull), in the province of Québec, stands the outstanding Musée Canadien de l‘Histoire I [map] (daily; free Thu 4–8pm; www.historymuseum.ca), which predominantly explores the history and society of Canada, and also the art and traditions of the native cultures and ethnic groups.

Cultural Gems

Ottawa’s National Gallery of Canada and, across the river, Gatineau’s Musée Canadien de l’Histoire, stand out both for their architecture and for their remarkable collections.

The airy glass-and-steel turreted National Gallery by architect Moshe Safdie (1988) houses Canadian painting from the 18th to the 20th centuries, including the Group of Seven; European and American works from Filippino Lippi to Francis Bacon; the reconstructed, fan-vaulted, Rideau Street Convent Chapel; and, since 2009, the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography’s collection, dedicated to work by Canadian photographers.

The photographic collection covers the history of the art from William Henry Fox Talbot through Eugène Atger, Walker Evans, and August Sander to the contemporary work of Diane Arbus and Man Ray. It is worth spending at least half a day at the gallery.

Dedicated to the human history of Canada, the Musée Canadien de l’Histoire, designed by Douglas Cardinal (1989), features the world’s largest collection of totem poles. All aspects of life in Canada, from the earliest native peoples to the arrival of Norsemen and successive waves of Europeans, are shown in eye-catching displays. Exhibitions of native art make this a museum not to be missed.

The unknown river

Author Hugh MacLennan, in Seven Rivers of Canada, describes the Ottawa as the “unknown” or “forgotten” river of Canada. As the St Lawrence superseded it as the principal trade route, the image of the Ottawa was dimmed and it took on the status of a short tributary linking the cities of Ottawa and Montréal. To the voyageurs and the lumbermen of early Canada, however, the Ottawa River was la grande rivière, the main route to the Upper Great Lakes and the western prairies beyond.

In the Ottawa Valley, running north of the capital to Pembroke and Deep rivers, the character of the old Ottawa river comes alive. At the Champlain Lookout 6 [map], high above the town of Renfrew, you can see the power of the river’s current as it bursts over narrows, and understand why the journey either up or down the Ottawa was dreaded by the voyageurs. The Ottawa Valley is full of tall tales of the bigger-than-big lumberjacks like Joe Mufferaw, who waged war on the forest to provide the British Navy with white pine masts. These are best heard in the Valley dialect, which is a complex mix of Gaelic, Polish, French, and Indian idioms.

Prince Edward County

Hwy 33 leads south from Hwy 401 to Prince Edward County, which locals simply call “the County.” A peninsula that juts into Lake Ontario, south of Belleville, it was settled by Loyalists in the 1780s. Though more and more people are discovering its charms, there is still an island-like sense of remoteness to this area. The highway becomes the Loyalist Parkway, the County’s main east–west artery, with lovely vistas of New England-style clapboard houses, of brick homes with gingerbread trim, and of Wellington Bay.

In Wellington, many older homes have been converted into restaurants and bed-and-breakfast places. The Wellington Heritage Museum (mid-May to mid-Oct Wed–Sun 9.30am–4.30pm; donation) is housed in a former 1895 Quaker meeting house and focuses mainly on the area’s Quaker history.

Antiques are big business along the main street of Bloomfield, as are gift and craft stores, artist galleries, and bed and breakfasts, mostly housed in historic buildings. The County is ideal for exploring by bike, which can be rented from the Bloomfield Bicycle Company on Main Street. Nearby, Slickers County Ice Cream offers all-natural ice cream that is made daily by hand, using fresh County products.

Picton 7 [map] is the county’s main town, with several historic buildings, including the County Courthouse and Jail on Union Street, where Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, began practicing law. Prince Edward County Museum (Victoria Day–Labor Day Wed–Sun 9.30am–4.30pm) is housed in the old St Mary Magdalene Church – part of the Macaulay Heritage Park complex – and provides an excellent overview of the County’s bygone days, including a fascinating presentation on Sir John and detailed exhibits on the town’s Loyalist connection.

Sailboats at sunrise, Picton.

Alamy

Arts and leisure around Picton

When the Regent Theatre opened in Picton in 1918, it was a rare example of an Edwardian opera house with a stage equal in size to that of Toronto’s Royal Alexandra Theatre. Barely surviving the whims of the entertainment industry during the 20th century, it too has been restored as close to its original state as possible, and is now the County’s center for the arts, with a year-round program of theater, first run movies, and alternative films, as well as festivals for chamber music and jazz.

The County has been attracting artists and artisans for years, drawn by its inspiring surroundings (and, perhaps, by the lower than big city prices). Studios of photographers and woodcarvers, weavers, sculptors, and painters are found down many a country backroad. Every year Picton hosts Art in the County (June–July for two weeks), a juried art show and sale, the Prince Edward County Studio and Gallery Tour (end Sept) and the Marker’s Hand (early Nov).

One of its most popular attractions is Sandbanks Provincial Park. Formed by a vast freshwater sand dune system, it’s a laid-back, family-orientated park, with giant sand dunes, three wide golden sandy beaches, and shallow waters that are perfect for windsurfing, sailing, and canoeing, as well as swimming in warm weather. Every spring, birdwatchers arrive in droves. The County’s sandy shoreline, limestone outcrops, lakes, forests, and wetlands attract over 300 species of birds.

Just east of Picton, there are over 20km (12 miles) of hiking trails in Macaulay Mountain Conservation Area, through both lowland and wooded escarpment. Birdwatchers come to see the likes of great crested flycatchers and winter wrens, others to see the quirky folk art of Macaulay’s Birdhouse City, in which many of the 100 birdhouses are colorful reproductions of local historic buildings.

Central Ontario

There are no firm borders separating eastern from western Ontario, let alone the east from the middle. But when classical limestone gives way to red-brick Victorian, that nebulous line has been crossed. Firmly within the orbit of Toronto, whose fatted-calf suburbs have gobbled up rich farmland with alacrity, the hamlets and towns of the region struggle to maintain their own character and traditions.

The town of Cobourg 8 [map], 96km (60 miles) east of Toronto, is just far enough away to remain relatively unscarred by bedroom dormitory blight. It, like its neighbors Port Hope and Colborne, was once a bustling lake port in the age of Great Lake steamers. The harbors are filled with pleasure sails now, but these small lakeside ports are the best places to appreciate the vistas offered by Lake Ontario.

The center of Cobourg is dominated by the neo-Classical Victoria Hall. Completed in 1860, it contains a courtroom replica of London’s Old Bailey, and is one of very few acoustically perfect opera houses in North America. In its time it served as a marvelous statement of Canadian pretensions to cultural superiority over the rebel Yankees. Here, the colonial elite had something solid to point to in explaining why they chose to remain impoverished British North Americans while Uncle Sam boomed.

Burleigh Falls in the Kawartha Lakes region.

iStock

Finger lakes with bones

To the immediate north of Cobourg, the long, thin Kawartha Lakes are strung like pegs on a clothesline tied to Lake Simcoe in the west. The Kawarthas have a pastoral appeal in contrast to the rugged beauty of the more northerly Canadian Shield Lakes. Rice Lake, the most southerly of the lakes, is especially beguiling. Framed by gently sloping drumlins bearing Holstein dairy farms on their elongated backs, Rice Lake is dotted with forested islands. Two thousand years ago, a little-known native civilization buried their dead by these shores in 96km (60-mile) long, snake-like ridges. Serpent Mounds Provincial Park 9 [map], 30km (19 miles) southeast of Peterborough, offers a cutaway viewing of the largest mound’s bones and burial gifts; currently closed for an extensive restoration project, it will be well worth visiting once it reopens.

Fact

By the time boaters reach Lake Simcoe from Lake Ontario they will have negotiated 43 locks and ascended 180 meters (590ft).

The Kawartha Lakes form the basis of the Trent-Severn Canal System, which allows houseboats and cabin cruisers to sail uphill from Trenton on Lake Ontario to Port Severn on Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay.

Peterborough ) [map], the center of the Kawarthas region, is the star attraction along the canal. Here the Peterborough Hydraulic Lift Lock, the world-champion boat lifter since 1904, boosts a boat up with one hand while sinking a second vessel with the other. Settled later than the counties along Lake Ontario, the Peterborough district was reputed in the 1830s to have the “most polished and aristocratic society in Upper Canada.” British army officers granted free land, and younger sons of the English gentry gave the backwoods of Peterborough and Lakefield a tone uncommon in earlier settlements.

Not that gentility made the hardships of pioneering any more bearable. Susannah Moodie, an early pioneer of Lakefield, and of Canadian literature, described in Roughing It in the Bush her feelings on being condemned to a life of horror in the New World, from which the only hope of escape was “through the portals of the grave.” Today, Peterborough seems to have found a middle ground between aristocracy and poverty, for it is a favorite testing ground for the arbiters of middle-class taste – the consumer-marketing surveyors.

Sunshine sketches of every town

There isn’t much of tourist interest in the town of Orillia ! [map], situated on the narrows between Lake Couchiching and Lake Simcoe, 96km (60 miles) north of Toronto – and that’s what makes it so interesting. To be sure, there’s a statue of Samuel de Champlain, noting the fact that he stopped nearby on his own Great Ontario Tour of 1615, but every town has a monument to someone or other.

No, the appeal of Orillia lies in the very ordinariness of the town: shady maples leaning over spacious side streets; wide front porches for socializing and spying; photographs of local hockey heroes in the barbershop-cum-agora. Stephen Leacock caught the flavor of the place – the flavor, for example, of Mr Golgotha Gingham, town undertaker who “instinctively assumes the professional air of hopeless melancholy” – in his book, Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town. A work of irony (one part affection, one part castigation), Sunshine Sketches won Leacock praise throughout the world when it was published in 1912. Everywhere, except Orillia. Now, Orillia has adopted the humorist as a favorite son and turned his home on Brewery Bay into a literary museum, the Stephen Leacock Museum (Mon–Fri 10am–4pm, in summer also Sat–Sun).

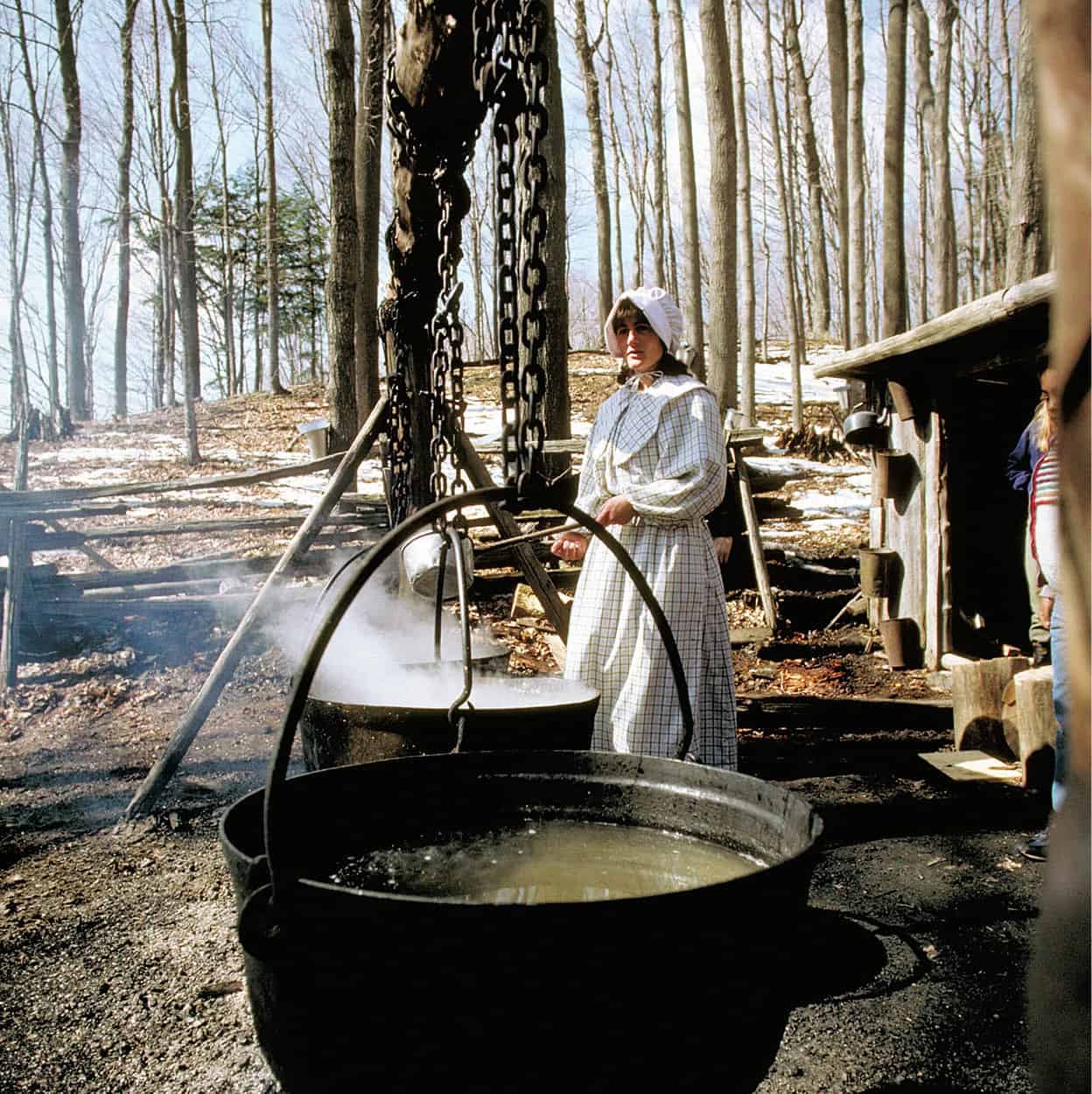

A “pioneer” makes maple syrup in the Kortright Centre for Conservation, Kleinburg.

Image Ontario

South of Lake Simcoe, 40km (25 miles) north of downtown Toronto, lies another shrine to Canadian artists: the McMichael Canadian Art Collection (May–Oct daily 10am–5pm, Thu until 10pm in July–Oct, Nov–Apr daily 10am–4pm) in the village of Kleinburg @ [map]. Started as a private gallery, the collection has grown into the finest display of the Group of Seven’s canvases in Canada, along with works by Tom Thomson, Group of Seven contemporaries, First Nations, Inuit, and other Canadian artists. The McMichael Collection, with more than 13 exhibition galleries housed in log and stone buildings, is the perfect place to feast on their labors.

Fact

The Group of Seven stood the Canadian art establishment on its head in the 1920s as they sought to portray the Canadian wilderness in all its Nordic harshness.

Southern Ontario

The excellent system of roads in southern Ontario is a sign of its long-accustomed prosperity. The Macdonald-Cartier Freeway, more widely known as the 401, spans the distance between Windsor in the west and the Québec border in the east. But it’s on the country roads that travelers begin to encounter southern Ontario: the rolling fields of corn, wheat, or grazing livestock; the majestic elms and maples that line the town streets and shady farm lanes; the graceful houses, ranging from the earliest log and stone dwellings in “American vernacular” style to stately Victorian and Edwardian homes in red and yellow brick; and the rivers. It’s difficult to drive anywhere in southern Ontario without crossing a creek, stream, or honest-to-God river.

Eat

Sample the sweet taste of rural Canada: the Maple Syrup Festival is held every spring, in Elmira, 10km (6 miles) north of Waterloo.

West of Toronto lies some of the richest farmland anywhere, and strung along those smooth roads are towns that sometimes seem to have forgotten how they got there. But fast food and video rental outlets notwithstanding, the pioneer experience has made a deep impression. Almost every town and village blossoms annually with a fair or festival. Maple syrup festivals. Apple cider festivals. Bean festivals. And everywhere are people who are determined to remember how they got there and what it was like before there were roads.

Loyalist settlers

With the capture of Fort Detroit in 1759, the British finally wrested control of the North American frontier from the French. But the settlement of the vast peninsula bounded by Lakes Ontario, Erie, and Huron lagged behind that of the booming colonies south of the Great Lakes. It wasn’t until those colonies declared their independence from Britain in 1776 that the wilderness that would one day be Ontario became inviting to settlers. These were the Loyalists, whose impact on Eastern Ontario has already been noted. Their contribution to the western part of the province is even more fundamental. They gave up established homesteads to start all over again in the bush, simply because that bush remained under British law. Yet these people were Americans, and the egalitarian sentiments and pioneering spirit they brought with them helped to shape Ontario.

Southwestern Ontario was sculpted into its present shape by retreating glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age. In the late 18th century this rich soil lay under a different kind of sea: a green, rolling swell of dense forest. The French had not seriously attempted to settle the land. Clearing away the giant trees and draining the swamps would have driven back the beavers whose pelts were so lucrative to the fur traders. For a time the British adopted this attitude as well.

Harvesting tomatoes in Leamington.

Image Ontario

The American War of Independence changed all this. Thousands of settlers from the Thirteen Colonies who feared or distrusted the new regime poured across the Niagara River. John Butler, the son of a British army officer, led a group of Loyalists north to Niagara. In 1778 he recruited a band of guerrilla fighters, who became known as Butler’s Rangers, and until the end of the war the group harassed the American communities in the area. Butler was stationed at Fort Niagara and charged with keeping the Six Nations, whose territory was south of Lake Ontario, friendly to the British. At this he succeeded, even persuading the Seneca and Mohawks to engage in fighting the rebels.

The leader of the Mohawks was Joseph Brant, who had received an English education and was committed to the British tradition. When the former Six Nations’ lands were ceded to the Americans in the 1783 treaty that ended the war, Brant appealed to the British for redress. He and his followers were given land beside the Grand river to an extent of 10km (6 miles) on either side. Part of that land took in Elora, where the Grand River has carved a canyon that has become one of the most popular retreats in southern Ontario. The only land that remains in the hands of the Six Nations of the Grand River is at Ohsweken, on the southeast outskirts of Brantford. Today it is one of Canada’s largest native settlements and is currently engaged in a controversial claim over land in nearby Caledonia.

The Niagara Escarpment.

iStock

Famous Falls

The Niagara Escarpment, a rolling slope that falls away in a rocky bluff on its eastern face, is another legacy of the last Ice Age. It rises out of New York State near Rochester, follows the shore of Lake Ontario around to Hamilton, snakes overland to the Blue Mountain ridge south of Collingwood, divides Lake Huron from Georgian Bay as the Bruce Peninsula, dips underwater, resurfaces as Manitoulin Island, disappears to emerge again on the western shore of Lake Michigan, and finally peters out in Wisconsin. The first farmers in the Niagara region had no idea of the extent of this formation, but they and their heirs discovered that the soil between the escarpment and the lake was very fertile.

Perhaps the best way fully to appreciate the richness of the land is to follow the Wine Route (www.winecountryontario.ca). From Country Road 24, some of the most glorious lake views are seen as the road descends into Vineland. The route eventually leads to St David’s and Niagara-on-the Lake. Some of Canada’s best wines are produced on the Niagara Peninsula, and the area’s 65 wineries are easily accessed by following the Wine Route signs; most offer tours and tastings, and several have acclaimed restaurants.

Niagara Falls.

iStock

The Niagara Falls £ [map], where Lake Erie overflows into Lake Ontario at the rate of 14 million liters (3.7 million gallons) of water per minute, have always been the most celebrated feature of the escarpment. Of his pilgrimage, Charles Dickens wrote: “We went everywhere at the falls, and saw them in every aspect… Nothing in Turner’s finest watercolour drawings, done in his greatest days, is so ethereal, so imaginative, so gorgeous in colour as what I then beheld. I seemed to be lifted from the earth and to be looking into Heaven.” Most would agree with Dickens and not with Oscar Wilde, who, noting the popularity of the Falls for honeymooners, remarked that “Niagara Falls must be the second major disappointment of American married life.”

The Falls, or rather the crowds that swarm around them, have attracted a host of sideshows over the years. Until very recently, the greatest carnival draw was Blondin, the French daredevil who first crossed over the cataract on a tightrope in 1859. In 1901, Annie Edson Taylor became the first person to plunge over the Falls in a barrel and live. These and other “daredevils” are remembered in the Niagara Daredevil Exhibition within the Imax Theater (6170 Fallsview Boulevard; daily 9am–9pm; free). On June 15, 2012, Nik Wallenda earned worldwide acclaim by becoming the first to successfully cross near the base of the Falls, rather than downstream, from the US to the Canadian side.

Fact

Niagara Falls have attracted many a stuntman, but none so bold as Blondin, whose high jinks on a tightrope above the cataract included stilt-walking.

The most popular way to approach the Falls is on a Maid of the Mist boat, which brings you to the very edge of the cascading wall of water. Wearing complimentary hooded raincoats for protection, visitors are boated up to the curve of the horseshoe close to the falls for a spectacular, if not intense, encounter with water. Journey Behind The Water is another attraction, reached on foot via an elevator through the rock from above, allowing you to emerge behind the falling water.

Tip

For a somewhat drier encounter with the Falls than aboard a boat, Konica Minolta Tower, 6732 Oakes Drive, and Skylon Tower, at 5200 Robinson, both have viewing platforms.

Niagara-on-the-Lake

John Butler and his Rangers founded the town of Newark at the mouth of the Niagara River after the American revolutionary war. In 1792, when John Graves Simcoe arrived, the place was called “Niagara-on-the-Lake.” It was the capital of Upper Canada, a province newly created out of the English-speaking portion of Québec. One of the first things Simcoe did was to choose a new capital, for Niagara-on-the-Lake was uncomfortably close to the US. He selected a site at a fork of the river, which he named the Thames. The capital would be called London (naturally). But Dundas Street was no sooner hacked out of the bush than Simcoe moved the capital to Toronto – which he promptly renamed York. The Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant once remarked: “General Simcoe has done a great deal for this province, he has changed the name of every place in it.”

Niagara-on-the-Lake $ [map] was blessed by its fall into political obscurity. It is one of the best-preserved colonial towns in North America. It’s also home to the annual Shaw Festival, a major theatrical event featuring the plays of George Bernard Shaw as well as works by other writers.

Tecumseh is killed by William Henry Harrison’s forces at the Battle of the Thames, 1813.

akg-images

The War of 1812

Canadian fears of American aggression were justified in June 1812 when the US took advantage of Britain’s preoccupation with Napoleon to declare war. Many Americans thought Canada would be a pushover. Isaac Brock, the military commander of Upper Canada, wrote of his predicament: “My situation is most critical, not from the disposition of the people… What a change an additional regiment would make in this part of the province! Most of the people have lost all confidence – I, however, speak loud and look big.” He acted swiftly and decisively. His troops captured Fort Michilimackinac in northern Michigan and repulsed an attack at the Detroit River. These early victories won the native peoples in the area to the British cause and galvanized the settlers.

Fact

A legendary figure of the 1812–14 war is Laura Secord, who overheard American soldiers planning an attack and walked through enemy lines to warn the British. Her former home, the Laura Secord Homestead, on the Niagara Parkway, is open to the public; see www.niagaraparks.com. There is a statue of her at the Valiants Memorial in Ottawa.

The Niagara region figured prominently in the war. The Americans attacked Queenston, just downriver from the Falls, in October 1812. Isaac Brock was killed in the Battle of Queenston Heights, though the town was successfully defended. The war dragged on, but without the example of Brock’s boldness, the heavily outnumbered colony might not have held out at all.

The War of 1812 gave Canada a stronger sense of identity, though it did not end the political divisions between Tories and those calling for democratic reform in the province. It also gave a signal to Britain that this colony was still too sparsely settled for its own security.

Southwestern Ontario

The northern shore of Lake Erie is bordered by dairy farms and fishing villages, tobacco farms and beaches. West of St Thomas, the land becomes mixed-farming country. This, the westernmost tip of southern Ontario, is the southernmost part of Canada.

Springtime at the Marsh Boardwalk, Point Pelee National Park.

iStock

Point Pelee National Park % [map] (daily), a peninsula jutting south of Leamington, 50km (30 miles) southeast of Windsor, is the southernmost part of mainland Canada. Lying at the same latitude as Rome and northern California, Point Pelee is home to plants and animals that are rarely seen in Canada. A trail through the woods and a boardwalk over the marshlands make it a living museum of natural history. The Jack Miner Bird Sanctuary at Kingsville (daily dawn–dusk; free), 10km (6 miles) west of the park, is one of the earliest and most famous waterfowl pit stops in Canada. This haven is free to migrating birds, butterflies and humans alike. Jack Miner said: “In the name of God, let us have one place on earth where no money changes hands.” The sanctuary is run by his family as a public trust.

The Underground Railroad

The southern border of Ontario played an unusual part in history: as one terminus of the “Underground Railroad.” In the early 1800s, runaway slaves from the American South were sheltered by sympathizers along several routes that led to Canada.

Reverend Josiah Henson, a self-educated slave from Maryland, made the trip with his family in 1830. He settled in Dresden ^ [map], 90km (56 miles) northeast of Windsor, and subsequently devoted himself to helping other fugitives. Henson was the prototype for “Uncle Tom” in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. His home in Dresden is part of Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site (mid-May to June, Sept–late Oct Tue–Sat 10am–4pm, Sun noon–4pm, July–Aug Mon–Sat 10am–4pm, Sun noon–4pm) that focuses on his life and works.

The city of Windsor & [map] is the biggest urban center on Canada’s border, a kind of half-sister to Detroit. Windsor is also an automobile industry town but, unlike Detroit, has a pleasant downtown with extensive parks and gardens on the riverfront. It is noted for its casino.

Fact

The name Ontario comes from the Iroquoian word meaning “shining waters,” an apt description for a province dominated by lakes of all sizes.

Lake Ontario

In the 1820s the growing towns and farms positioned along the western curve of Lake Ontario continued to nibble at the wilderness around them. Ancaster, Dundas, Stoney Creek, and Burlington all eventually lost their bids for supremacy at the lakehead to the town of Hamilton * [map], the “ambitious little city,” 70km (43 miles) south around the lake from downtown Toronto.

The Niagara Escarpment, referred to locally as “the mountain,” divides Hamilton into split levels. The city’s steel mills and other heavy industries have given Hamilton a grim image in the minds of many. But the somewhat misleadingly named Royal Botanical Gardens incorporate a wildlife sanctuary called Coote’s Paradise, with trails winding through 485 hectares (1,200 acres) of marsh and wooded ravines (indoor Mediterranean Garden daily 10am–8pm; outdoor gardens seasonal: daily 10am–dusk; www.rbg.ca).

Inside Dundurn Castle, Hamilton.

Image Ontario

Hamilton’s architectural jewel is Dundurn Castle (Tue–Sun noon–4pm). Sir Allan Napier MacNab – landholder, financier, all-round Tory, and Hamilton’s first resident lawyer – had it built in 1835 as a lavish tribute to himself. The finest home west of Montréal at the time and named for MacNab’s ancestral homeland in Scotland, it is now restored as a museum to reflect the 1850s, when MacNab was premier of pre-Confederation Canada.

Fact

Hamilton installed the first telephone exchange in the British Empire in 1878, only four years after Alexander Graham Bell invented the device. It was at his parents’ home in Brantford that Bell dreamed up the idea.

The first thing to note about nearby Kitchener ( [map], 40km (25 miles) north of Brantford, and Waterloo is how prosperous they are. Kitchener is one of the fastest-growing municipalities in Canada. The second thing to note about the Twin Cities is how German they are. The original settlers in the area were members of the austere Mennonite sect transplanted from the German communities of Pennsylvania in the 1780s. The Mennonites soon had German neighbors of various creeds, and today Kitchener and Waterloo host North America’s biggest Oktoberfest (week-long in mid-Oct). “Good cheer” is spelled Gemütlichkeit in this part of the country.

Fact

For the Oktoberfest, Kitchener and Waterloo sprout 15 “festhallen” where sauerkraut, sausage, and beer are enjoyed to the cheery beat of oompah music.

Ten kilometers (6 miles) north of Kitchener, the village of St Jacobs , [map] was settled in the 1840s by German Mennonites. Many heritage buildings along Front Street have been converted into artisan studios and attractive stores. Among the casually attired shoppers, local Mennonites are solemnly dressed in black, the women in bonnets and the men sporting dark, broad-brimmed hats. They come here to sell their farm produce and hand-made quilts, and are often seen bowling along the country roads in their horse-drawn buggies.

Market day in St Jacobs.

Courtesey of St Jacob County

On King Street, The Mennonite Story Visitor Centre (Apr–Dec Mon–Sat 11am–5pm, Sun 1.30–5pm, Jan–Mar Sat 11am–4.30pm, Sun 2pm–4.30pm; donation) explains the history, culture, and religion of the Mennonite people. Founded in 1525 in Switzerland during the Reformation, they established the first “free Church” and introduced the now widely accepted principle of separation of Church from state. Considered revolutionaries, they were severely persecuted for several generations, before migrating first to Pennsylvania and then, after the American Revolution, to this corner of southern Ontario.

Celebrating the Oktoberfest at Kitchener.

Image Ontario

A few miles west of the village, St Jacobs Farmers’ Market (year-round Thu and Sat 7am–3.30pm, mid-June to Aug also Tue 8am–3pm) is a huge farmers’ market that attracts shoppers from as far away as Toronto. Besides stalls overflowing with fresh Ontario produce, it peddles all things maple – syrup, butter, fudge, even lollypops – and old country specialties such as homemade perogies, butter tarts, German apple cake, or raspberry apple cobbler. Somewhat incongruously, the St Jacobs Outlet Mall across the street offers a 21st-century shopping experience, with more than 20 stores selling discounted top-name brands.

Art, the Environment, and War

Long known as Steel City because of its steel industry, Hamilton is a place that few people, especially Torontonians, would have considered as a great day out. Today, however, this gritty steel town is transforming into a cultural hub – partly as cheaper rents and properties have attracted many Toronto-area artists.

Downtown, the Art Gallery of Hamilton is Ontario’s second-largest art gallery. Within its striking gold-and-glass exterior, an exceptional collection of Canadian art can be viewed. The city has also overseen a massive environmental clean-up of its harbor and waterfront, to create a much-loved outdoor playground. A good way to explore is to follow the Hamilton Harbour Waterfront Trail from the nature sanctuary of Cootes Paradise, past the historic Desjardins Canal to the west harbor, a path shared by cyclists, runners and dog-walkers, night herons and mute swans. For a different experience of history, visit the HMCS Haida, a Tribal Class destroyer that saw active service during World War ll and is now a National Historic Site of Canada. On the periphery of Hamilton International Airport, the Canada Warplane Heritage Museum captures the magic of flight with displays on Canada’s aviation history. One of its biggest attractions is the only operational Lancaster bomber in North America, and one of only two in the world.

The Huron Road

In the 1820s, the land between Lake Huron and the modern site of Kitchener was a piece of wilderness called the Huron Tract. The development of this, and other bits of Crown land, was the ambition of the Canada Company. The company’s success can be attributed to its first superintendent of operations, the Scottish novelist and statesman John Galt, and to his chosen lieutenant, Dr William (Tiger) Dunlop. Galt’s first task was founding a city on the edge of the wilderness. Guelph, 15km (9 miles) northeast of Kitchener, was inaugurated in April of 1827 and it is a striking collection of 19th-century architecture. The Roman Catholic church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception dominates the skyline with twin Gothic towers.

After surveying the Huron Tract, the exuberant Dunlop had pronounced: “It is impossible to find 200 acres together which will make a bad farm.” Galt wanted a road so that settlement could begin in earnest. In 1828, Dunlop directed the construction of that road, through swamps, dense forest, and tangled brush. Work was slow and fever plagued the work camps. It was a stupendous achievement that is not diminished by the many improvements the road has seen since. Now Highway 8, the Huron Road became the spine of settlement in the tract.

A musical moment in Peterborough County.

Image Ontario

Eighteen kilometers (11 miles) into the bush, the first Huron Road curved at an attractive meadow by a river. Before long the settlement that sprang up there was called Stratford ⁄ [map], and the river the Avon. The connection to Shakespeare was strengthened in the naming of wards and streets (Romeo, Hamlet, Falstaff), while Stratford boomed in the 1850s by virtue of being the county seat and at an intersection of railway lines.

In the years after World War II, Stratford native Tom Patterson was persistent, and finally successful, in peddling his dream of a Shakespearean theater for the city. On July 13, 1953, Alec Guinness stepped onto a stage in a riverside tent as Richard III, and the rest, as they say, is history. The tent-like (but permanent) Festival Theatre was opened in 1957, and its “thrust stage” has influenced a generation of theater-builders. The Stratford Festival now includes three other stages (the Avon Theatre, the Third Stage, and the Studio Theatre) and features music as well as plays. Over 500,000 people are attracted to the town annually.

Another road that helped to open up the Huron Tract is the one north from London ¤ [map], 60km (37 miles) south of Stratford. Or south to London, if you like, because all roads in southwestern Ontario eventually lead to London. Failing to become the capital of Upper Canada, London stayed small until it became the district seat in 1826. British tradition and the American feeling of wide open spaces are in harmony here. On the street signs of London such names as Oxford and Piccadilly mix with names from Ontario’s history like Simcoe, Talbot, and, of course, Dundas Street. Other names, like Wonderland Road and Storybook Gardens, may lead visitors into thinking that they have stumbled into a kind of Neverland. The impression will be reinforced by the squeaky cleanness, and greenness, of this relentlessly cheerful city. It isn’t called “the forest city” for nothing; from any vantage point above the treetops, London visually disappears under a leafy blanket. The River Thames flows through the campus of the University of Western Ontario, a school whose presence is definitely felt in town. Also in London is the Fanshawe Pioneer Village (Victoria Day to Thanksgiving Tue–Sun 10am–4.30pm, Thanksgiving to Victoria Day Tue–Fri 10am–3.30pm), a fascinating reconstruction of a pre-railway, 19th-century town, equipped with log cabins, a general store, a weaver’s shop, and a carriage-maker’s quarters.

Kids

Storybook Gardens in London’s Springbank Park are fun for young children. Here they can meet Willie the Whale and The Three Bears, and take a boat ride on “Tinkerbell.”

Western Ontario and Lake Huron

In Ontario Ministry of Tourism language, the Lake Huron shoreline is called Bluewater Country. It is a glorious lakefront with cottages, beaches, and places like Bayfield, 75km (46 miles) north of London. This village, with its intact 19th-century main street, shady beach, and fine marina, is a gem.

Lying 21km (13 miles) farther north is Goderich ‹ [map], Tiger Dunlop’s town. Not merely planned, Goderich was designed; the County Courthouse sat on an octagonal plot (called The Square) from which streets radiated in all directions. Sadly, Goderich’s claim to be “The Prettiest Town in Canada” was undermined by a devastating hurricane on August 21, 2011, when many of the old buildings and trees were severely damaged. Now the town has largely been restored and some of the most spectacular sunsets on earth can be seen from this spot. In fact, that goes for the whole of the Huron lake shore, including popular resort towns such as Southampton and Sauble Beach, whose wide sandy beaches have been attracting generation after generation of Ontario families.

When they saw how quickly the Huron Tract was being gobbled up, the British government threw open for settlement the First Nations territory immediately to the north of it. The Queen’s Bush, as it was called, was not as fertile as land farther south, and some of the boom towns soon went bust. Those that remained on the stony soil turned to raising beef cattle. Several railroads snaked into Ontario between 1850 and 1900. Towns along the routes prospered, especially those where lines crossed. But as the rail lines fed city factories, industries in small towns declined and the smallest towns focused solely on the needs of the surrounding farming communities.

From Goderich to Manitoulin

In the 1970s there was a swell of interest in the history and architecture of Ontario’s small towns. A good illustration of this is the Blyth Festival. A community hall was built in 1920 in Blyth, 33km (20 miles) east of Goderich. Upstairs in the hall is a fine auditorium, with a sloping floor and stage, which lay unused from the 1930s until the mid-1970s when it was “discovered” and refurbished as the home for an annual summer festival dedicated to Canadian plays, most of them new, and most of them celebrating small-town and farming experiences. That the Blyth Festival has become a favorite with Canada’s urban drama critics indicates both its theatrical quality and the potency of its subject matter, namely the history and people of rural Canada.

About 17km (11 miles) south of Blyth on the literary map lies Clinton, the home of writer Alice Munro, winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize in Literature. Her beautiful stories transcend regional interest and “local color.” There is no better introduction to the life of small-town Ontario.

A view in Tobermory.

iStock

This region has always been sparsely settled; the soil is thin, and navigation on the lake hereabouts can be treacherous. But many people make the effort to reach Tobermory › [map], the fishing community at the tip of the 80km (50-mile) long Bruce Peninsula fi [map]. The peninsula is bordered by Lake Huron’s warmer and shallower waters to the west, while the Georgian Bay side is dominated by the Niagara Escarpment – a rugged wall of limestone that climbs to 100 meters (328ft) in places. On Colpoy’s Bay, Wiarton is the gateway to the peninsula. Steep cliffs flank the harbor, providing a striking setting and sheltered waters for sailing and fishing. Across the peninsula are Oliphant and Red Bay, neighboring communities where families come for good beaches and safe waters. Farther north, 11km (7 miles) beyond Dyer’s Bay, the Cabot Head Lighthouse (Victoria Day to Thanksgiving daily; donation) houses a small museum of local history, while the adjacent Wingfield Basin Nature Reserve is frequented by 120 species of birds, ranging from the snowy owl to the great blue heron.

Bruce Peninsula National Park encompasses the northern tip. Its dense forest cover is a botanist’s delight. Birders are also handsomely rewarded here, and the hiking is exceptional. Just off Tobermory lies Fathom Five National Marine Park. Encompassing 19 islands and at least 22 shipwrecks, it is one of North America’s premier diving sites.

Through the season, Tobermory is action-packed, especially when Little Tub Harbour is jammed with dive and cruise boats. Some visitors are heading north for Manitoulin Island fl [map], the largest freshwater island in the world, on board the giant ferry Chi-cheemaun (big canoe). Measuring 176km (110 miles) long with more than 80 inland lakes, Manitoulin is known for its tranquility and natural beauty. Wikwemikong is an unceded First Nations reserve that is known for hosting North America’s largest Pow Wow each August and for its rich cultural heritage (a high number of internationally known First Nations artists hail from here, including Daphne Odjig, Leland Bell, and Jim Mishibinijima).

M’Chigeeng (formerly West Bay) is the second-largest native community on the island. Here, the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (mid-June to mid-Oct Mon–Fri 8.30am–4pm, Sat 10am–4pm; free) showcases the work of many local artists. Over the road, the Immaculate Conception Church is a striking circular building that blends traditional Christian and Native cultures. Little Current is the island’s largest town and a popular port of call for Georgian Bay’s extensive yachting community.

Fact

Studded by islands, Georgian Bay is a popular sailing area. Its coastline varies from the white sands of Wasaga Beach in the south to the rocky northern shore.

South of Georgian Bay, on the eastern ridge of the escarpment, a range of large hills provides the best ski-runs in Ontario. Ontarians call these the Blue Mountains, but not too loudly in the presence of anyone from western Canada.

Sainte-Marie, among the Hurons historic site.

iStock

Ste Marie Among the Hurons

To visit the small peninsula poking out into Georgian Bay is to step a little farther back into history than most places in rural Ontario permit. This area is called Huronia, where 350 years ago French Jesuit missionaries traveled and preached among the Huron Indians.

When the lonely fortified mission of Ste Marie Among the Hurons was established in 1639, it was the only inland settlement of Europeans north of Mexico. It prospered for 10 years; but the Huron nation was eventually destroyed in wars with its enemies, the Iroquois, who also tortured and killed the Jesuits. Brian Moore’s 1985 novel Black Robe (which was made into a movie in 1991) are set against this backdrop. Ste Marie was not attacked, but the fort was burned by retreating Jesuits to keep it out of Iroquois hands. After much research, the mission and its everyday life have been recreated on a site 5km (3 miles) east of Midland ‡ [map] (mid-May to mid-Oct daily 10am–5pm, mid-April to mid-May and mid–end Oct Mon–Fri 10am–5pm). It was in this area that Fathers Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalament were tortured and then brutally killed by the Iroquois in 1649. Their remains were housed across from the mission in the Martyrs’ Shrine, a towering edifice that commands a spectacular vista over the surrounding country. Nearby is Wye Marsh Wildlife Centre (daily 9am–5pm; July–Aug Fri until 8pm; www.wyemarsh.com) with boardwalks extending over the marshlands. A visitors’ center explains the ecology of the area and features guided tours.

The many thousands of lakes in Ontario and, particularly, those in the Canadian Shield region, just to the north, provide a cherished escape for city dwellers. The settlers’ war of extermination against the trees has given way to a desire to preserve the woodlands and waters of the near north for recreational purposes.

Georgian Bay shore at Bruce Peninsula Provincial Park.

iStock

However, the Georgian Bay, Muskoka, and Haliburton regions can no longer be described as forested wilds, dotted as they are by thousands and thousands of cottages. Ontario is one of the few places in the world where seemingly everyone, rich and not so rich, has a country estate even if it’s only a humble cabin.

An Unusual Hero

Countless Canadians of Chinese descent, and increasingly more visiting Chinese nationals, have been making a pilgrimage of sorts to the birthplace of a Canadian surgeon who died in China in 1939 while treating Mao Zedong’s troops. The son of a Presbyterian minister, Norman Bethune was born in the Muskoka resort town of Gravenhurst. From these ordinary, middle-class beginnings, he trained in medicine, served as a stretcher-bearer in World War l, then declared allegiance to the Communist Party and developed the first mobile blood transfusion service while serving in Spain’s Civil War. From there he headed to China and the second Sino-Japanese War. Before his death, he had built hospitals and medical schools while continuing to look after wounded soldiers. To this day he is revered in China, where innumerable memorials have been erected in his name, and every house in which he lived has been converted into a museum. In 1976 Parks Canada converted the Presbyterian manse in which he was born into a Canadian memorial and in 2012, a new visitor center in his honor opened in Gravenhurst. Its intent is to educate the many Chinese visitors on his Canadian origins and others – including Canadians – on his pivotal role as a humanist and doctor in China.

A canoe with a view in Algonquin Provincial Park.

Image Ontario

Algonquin Provincial Park

To the north of Haliburton and the northeast of Muskoka lies the last real expanse of wild land in southern Ontario – the 7,600-sq km (2,934-sq mile) Algonquin Provincial Park ° [map] (Visitor Center, see www.algonquinpark.on.ca for hours). Set aside as a provincial park in 1893, Algonquin preserves the primordial, aboriginal, and pioneer heritages of Ontario as a kind of natural museum.

Tip

Entry to Algonquin Provincial Park is by permit (arrive early or book ahead, tel: 705-633-5572). Avoid peak vacation times if you plan to explore by canoe.

Loons, the oldest-known birds, abound in the park’s 2,500 or more lakes as they did 10,000 years ago after the last Ice Age. Algonquin Indian “vision pits” can be found in the northwest corner of the park. Here, in these rock-lined holes, a young Algonquin would fast for days waiting for the vision of a spiritual guardian who would draw the rite of passage to a close. In the park’s interior, east of Opeongo Lake, lies the last stand of great white pines in Ontario. These few dozen ancient pines are all that is left of the huge forests cut to provide masts for the British Navy.

Algonquin should be seen by canoe. Heading north on Canoe Lake away from the access highway, it is only one or two portages before the motorboats and “beer with ghetto-blaster” campers are left behind. In the interior, porcupines, beaver, deer, wolves, bear, and moose can all be seen by canoeists. In August, park naturalists will even organize wolf howls, where campers head out en masse at night to try and raise the cry of the great canines. The loons, however, need no such encouragement. Their haunting cry, which the Cree believed was the sound of a warrior who had been refused entry to paradise, can be heard on every lake.

Each season brings its own character to Algonquin. Spring is the time of wild flowers, mating calls, white water, and blackflies as thick as night. Summer brings brilliant thunderstorms, mosquitoes in place of blackflies, acres of blueberries, and water actually warm enough to swim in. In the fall, Algonquin turns into a Group of Seven canvas. The funeral for the forest’s leaves is as triumphant and colorful as that of any New Orleans jazz singer. Uniform green gives way to a kaleidoscope of scarlet, auburn, yellow, and mauve, while in the winter, in total contrast to the rest of the seasons, the park falls deathly silent as it waits for the resurrection under a mantle of snow.

Algonquin, however, is not without its problems, problems typical of an urban society unable to control its effect upon the natural environment. Not only is most of Algonquin under license to logging interests, whose long-term effect on the ecosystem cannot be gauged; it is also being scarred by the ever-increasing effects of industrial pollution.

A snowy forest in Temagami.

iStock

Northern Ontario

Highway maps of Ontario divide the province in two: one side showing southern Ontario, the other northern. Sudbury · [map], 390km (242 miles) north of Toronto, is called “the gateway to the north” and it marks the boundary between the two. It is a city of 164,000, known for its copper and nickel mines, and its cultural focus points include Science North (daily, end June to Labor Day 9am–6pm, Labor Day to end June 10am–4pm), an interactive museum for families, and a lively summer music event, the Northern Lights Boréal Festival.

Most travelers never give the north of Ontario a look, never turn over the map. Myth has it that northern Ontario is an endless tract of conifers, lakes, bogs, mining camps, moose, and mosquitoes. Like all myths it’s true in part, but only in part.

Just north of Algonquin Park is the Near North region of lakes and pristine wilderness areas, such as Temagami, toward the Québec border. Not far from North Bay, the region’s largest center, is Temagami Station. Here, Grey Owl, the Englishman who successfully posed as a native environmentalist writer in the 1930s in the UK and US, lived and wrote.

Cars taper off along northern highways, and settlements are farther apart. Every second vehicle is a logging truck. One of the most popular routes into the wilderness, which Canadians call “bush,” is aboard the Polar Bear Express. It leaves every day but Saturday, late June to late August, from Cochrane, a place of fishing poles and down vests, to the Arctic tidewater towns of Moosonee and Moose Factory. The adventurous bring their own canoes and paddle on to the isolated James Bay outposts.

Lying 296km (184 miles) west of Sudbury, Sault Ste Marie is a cultural and sporting center, whose attractions include the 183km (114-mile) Agawa Canyon train tour (end June to mid-Oct daily) and, for the angler, the largest fish hatchery in Ontario.

Located at the top of the Great Lakes, some 700km (435 miles) north of Sault Ste Marie, Thunder Bay’s location is hard to beat. Surrounded by unspoiled wilderness – a constant source of inspiration to the city’s many artists – it is backdropped by the Nor’Wester Mountains. On its doorstep, a string of islands entice kayakers, sailors, and hikers. The Sleeping Giant, a massive series of mesas at the tip of the Sibley Peninsula, forms an impressive guardian to Thunder Bay’s harbor. With more than 80km (50 miles) of hiking trails, the Sleeping Giant Provincial Park’s backcountry offers a world of peace and solitude.

Farther west still is the Lake of the Woods district and Kenora, a pulp and paper center, near the Manitoba border. This land rivals the Muskokas for resorts and bluewater camping. For those whose idea of Canada is a place where you contract a bush pilot and sea plane and fly in to an isolated cabin for a week or two, Lake of the Woods fits. “Fly-in” resorts are extremely popular, with loons, sunsets, a moose or two, and ads that read, “Ask for Don or Lynn.” Now that’s northern Ontario.

Old Fort William

In northwest Ontario, Thunder Bay’s Fort William Historical Park brings early Canadian history to life, at the inland headquarters of the North West Company (NWC) and what was the world’s largest fur trade post. The fort’s raison d’être was beaver fur, which played a key role in forming the foundations of Canada. Here, in a good year, up to 90,000kg (200,000lbs) of fur (mainly, but not only, beaver) was shipped off to faraway lands to make top hats.

The fort on the Kaministiquia River has 42 historic buildings spread over a 10-hectare (25-acre) site, and is a faithful recreation of the original fort that was operated by the Nor’Westers from 1803 to 1821, with costumed interpreters bringing the early 1800s dramatically to life, whether they’re working on the farm, in the apothecary or in the kitchen. A slice of pivotal Canadian history comes to life even more if you sign up to learn a heritage craft from some of Old Fort William’s gifted artisans – whether it’s the fort’s modern-day tinsmith, fashioning items from hurricane lanterns to foot baths, butter churns, and measuring pots, or the cooper, crafting rawhide drums around wooden frames. Workshops such as these provide marvelous insight into life as it was 200 years ago.