Many would picture the Northwest Territories as a flat and perennially icy slab stretching from the 60th Parallel toward the North Pole, with the occasional polar bear or Inuit igloo to give some relief to the unvarying landscape. However, the landscape is anything but monotonous, and it is not one land but a multitude of lands – lands that are foreign to most people, and yet so mystical that each person who visits there is not so much a tourist as an explorer.

The Northwest Territories cover an immense area of almost 1.2 million sq km (over 450,000 sq miles). To gain some insight into how large this is, combine Spain, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Belgium. The southern border touches Saskatchewan, Alberta, and part of British Columbia, along the 60th Parallel and stretches 3,400km (2,110 miles) up to the North Pole. This means that the total land mass of the N.W.T. (officially abbreviated to NT, but commonly referred to as N.W.T.) is larger than Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana combined, yet the area has a population of a mere 44,000.

More than half of these residents are aboriginal, some of whom have ancestors that lived on this land since the last Ice Age.

Inuit in caribou fur.

Getty Images

Scars of the Ice Age

Venturing north above the tree line into the tundra, where it is too cold for lush vegetation and forests to survive, the scars of thousands of centuries of geological history stand before the eyes. It was only 10,000 years ago that the last Ice Age, the Pleistocene, finally retreated from much of the area, leaving behind moraines, dry gravel beds, and drumlins.

There are also thousands of rivers and lakes that cover more than half of the territory’s land mass. Many of these lakes and rivers, particularly those in the Mackenzie delta, were formed by glaciers creating indentations in the earth and leaving behind melted glacial ice.

A River Runner’s Dream

The idyllic rivers of Canada’s Northwest Territories are untamed, unpolluted, and flow through hundreds of miles of unmatched wilderness, offering some of the most wonderful and stimulating paddling experiences in the world. In boreal forest rivers including the Nahanni, the Natla-Keele, the Mountain, or the Slave, deep canyons, rapids, and spectacular plunging waterfalls prove great challenges to the paddler, whitewater canoeist, and photographer alike.

Farther north, Arctic rivers also have incredible appeal, meandering their way through the expansive open tundra, where the majority of plants grow no taller than a foot (30cm/12ins) high, and where great wildlife spectacles may include the midsummer migrations of the caribou or grizzly bears and tundra wolves.

Rivers and lakes notwithstanding, much of the territory is classified by geographers as desert. The stereotypical picture of the Canadian North being smothered in snow is surprisingly inaccurate. In fact, the mean annual precipitation for both the eastern and western Arctic is only 30cm (12ins), which is the equivalent of just a single Montréal snowstorm.

During the long Arctic winters, however, the sun may only appear for a few brief hours, if at all, so whatever snow does fall will not melt until spring. Temperatures in the region are legendary. At Inuvik, the territory’s capital, two degrees north of the Arctic Circle, the average winter temperature drops to a perishing –31°C (–24°F) at night, with a record low of –56°C (–70°F), while in July, its warmest month, it averages close to 20°C (68°F) and is more frequently than not closer to 30°C (89°F).

Tip

To view the tundra and mountains north of the Arctic Circle, take the 730km (450-mile) Dempster Highway from Dawson City, Yukon, to Inuvik, NT.

For a traveler trying to plan what clothing to pack for an adventure – which is what any trip to the Northwest Territories will be – the standard rule of lots of layers applies. The temperature may vary, but one thing does not. When summer arrives here the sun only just dips into the horizon before beginning its slow upward journey, and conditions are ideal for hiking or camping. In fact, summer in this region is remarkably similar to that in the rest of Canada, except of course that there is more sunshine and a much lower probability of rain.

Salt flats, Wood Buffalo National Park.

Getty Images

Breeding grounds

While the Northwest Territories receive relatively few human visitors, it is estimated that 12 percent of North America’s bird population breeds here during the spring and summer months. Close to 300 species are tracked here, with biologists looking to learn more about migratory habits. They believe that one of the main attractions to this part of North America is the relative lack of predators and, in summer, an abundant source of food.

This is a birder’s paradise, as it provides the potential of seven different species of owl, and a huge variety of eagles, hawks, and other raptors. Ocean birds, shore birds, and even songbirds can be spotted here, provided the right planning is undertaken. The land is so vast that it makes sense to rely on the tour operators who cater to keen birders and photographers for help with itineraries and timing.

The Northwest Territories are a birdwatcher’s paradise.

iStock

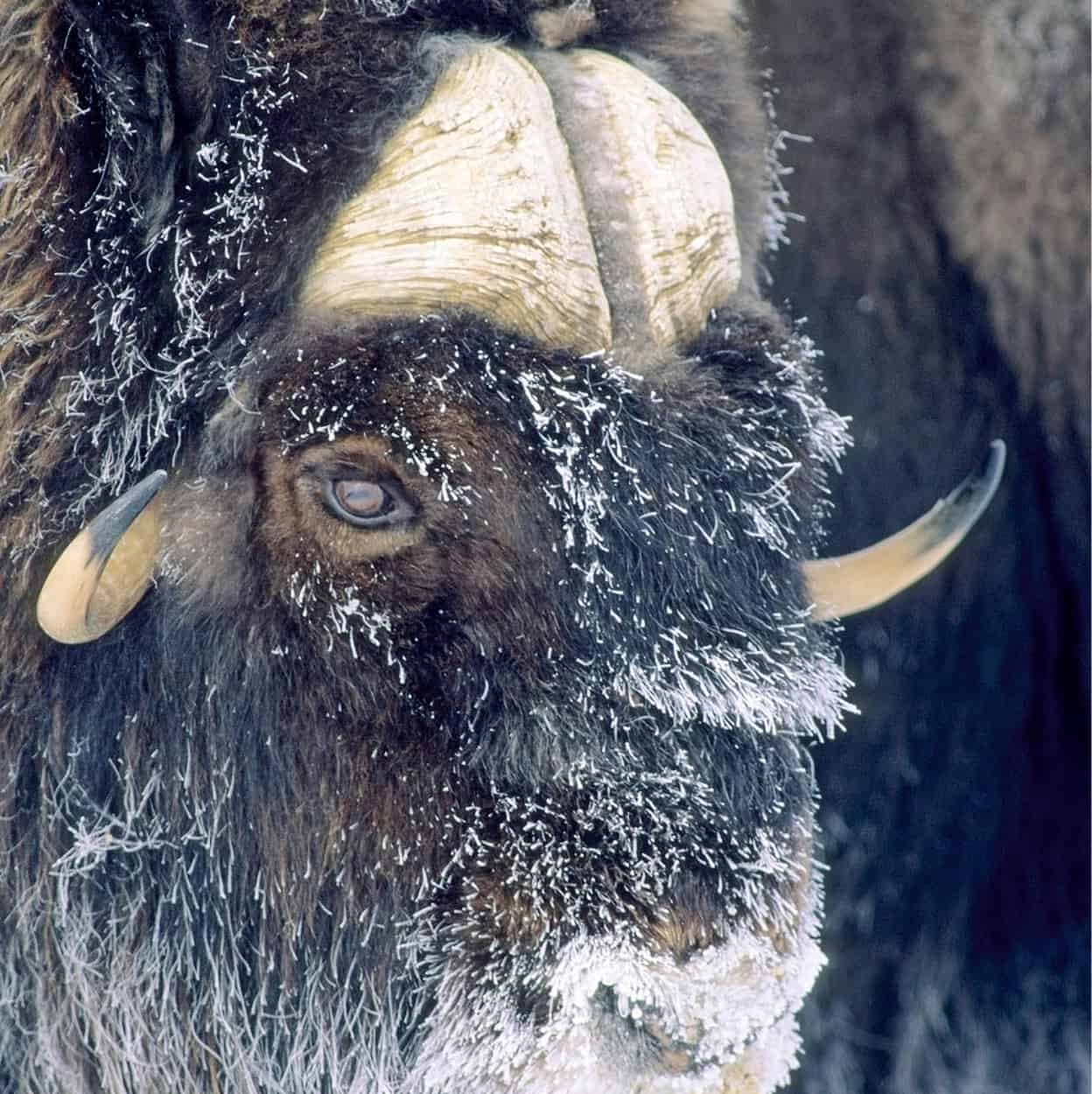

Below the tree line, where the weather is less harsh and the trees offer protection from the elements, there are moose, beaver, marten, muskrat, red fox, timber wolf, and black bear. Massive herds of caribou migrate from their traditional calving ground near the Beaufort Sea southward. In select areas, the largest mammal in North America, the wood bison, also roams the grassy plains. Above the tree line there are arctic wolves with white coats, as well as arctic fox and lemmings. Along the coastline and on the islands polar bears, seals, walrus, and even lemmings can be seen. Banks, Victoria, and Melville islands in the far north are inhabited by the exotic, hirsute musk ox.

Tip

Just to the east of the Yukon, Nahanni National Park has gorges deeper than the Grand Canyon. Visit Fort Simpson to arrange tours, flights, and canoe rentals.

The tundra and climate change

Perhaps one of the most remarkable facts about survival on the tundra is the dependency of all life on soil frozen to a depth of between 30 and 300 meters (100 to 1,000ft). This ground is appropriately called permafrost. During the summer, the sun’s rays are able to melt topsoil here to a depth of 24 meters (80ft). It is within this layer of soil that small organisms, including lichen, grow. Lichen and low-lying vegetation are a main source of food for the mammals of the tundra.

In the summer season that is too short in length for plant life to grow, all species suffer losses. Decimated species eventually recover and restore the natural order, but this order becomes a precarious one and any external force can disrupt the fragile ecosystem. It is for this reason that the intrusion of southern development is seen as a dangerous threat.

The Canadian North is being closely examined by scientists concerned about climate change. As they observe the impact of the recent increases in temperature experienced here, they are trying to put the changes in the context of the delicate ecosystem and the countless plants and animals that have adapted themselves to survive here. Measuring the changes in permafrost temperatures and depth of seasonal freezing/thawing are key indicators of changes of climate in the Arctic.

Catch sight of the aurora borealis, or Northern Lights, here from late August through March, when the night sky comes alive with a dazzling display of colors.

Boats wait for the spring thaw on the Mackenzie River.

iStock

Early explorations

Since the first European explorers, the North has held a sense of mystery for all outsiders. Many believed there were untold fortunes to be made there, so they approached it with this in mind.

The first recorded European exploration of the Arctic was undertaken by the Elizabethan, Martin Frobisher, who searched for gold and the elusive Northwest Passage in 1576. Frobisher found neither gold nor the Passage on his first or many subsequent journeys. However, he did manage to bring back to England 700 tonnes of fool’s gold from Baffin Island (now part of Nunavut).

Henry Hudson was another intrepid English explorer who set out to find the Passage. Hudson traveled extensively in the North for several years. Not only did he fail to find the Northwest Passage but his long-suffering crew mutinied, causing havoc. Hudson, his son, and seven other explorers were set adrift in a barque in the bay that now carries Hudson’s name. The nine men were never seen again. Owing to the discouraging results of expeditions undertaken by Frobisher, Hudson, and others of the era, the British Crown and other financial backers became disenchanted and abandoned the search for a northerly route to the Orient and India.

Within Canada, fur traders were searching for routes to markets in Europe. One such entrepreneur was Alexander Mackenzie, who in 1789 followed the Mackenzie river for its entire length (4,240km/2,630 miles) in the hope that it would eventually lead to the Pacific Ocean. It led instead to the Arctic Ocean. Little did Mackenzie realize in the 18th century that he had reached an opening to a sea that covered vast and lucrative oil deposits.

Even though this area had proven to have little commercial value in the 17th and 18th centuries, there were those in England during the 19th century who looked toward the Arctic region with a mixture of wide-eyed romanticism and genuine scientific curiosity. This era in Arctic exploration was similar to the period of space exploration of the 1960s and 1970s. The British Parliament offered prizes to any person who could find the Northwest Passage and/or discover the North Pole.

Daring explorers include William Parry, who managed to collect a purse of £5,000 for his excursion to the far Western Arctic islands (1819–21), and John Franklin, who, in characteristic, bloody-minded British bulldog manner, regularly risked his life while mapping the Arctic coastline.

On his final journey in 1845, Franklin departed from England with a crew of 129 men aboard two ships; their lofty objective was to find the Northwest Passage. Unfortunately the ships were locked in the ice for two years at Victoria Strait. In 1848, search parties were sent out, and eventually over the next eight years articles of clothing, logbooks, and mementos were found strewn across the chilly coastline. Of the 129 men on the Franklin expedition not one survivor was found.

A lynx on the prowl in an aspen forest.

iStock

Traveling today

Today, however, travel to the Arctic is thankfully a great deal less hazardous. After the Franklin debacle, “outsiders” began to pay attention to the ways of the Inuit, the Dene and other First Nations peoples who had not only survived in the North for millennia, but had also developed rich cultures with strong oral traditions, passing on practical information about how to thrive in such extreme and difficult conditions.

With the arrival of the airplane in the early 1920s, the Northwest Territories became far more accessible to the outside world. Air travel is now both routine and safe in the Territories. To reach many communities, air routes have become the “real” highways for the North. The area is served by several airlines from major cities in Canada to all large communities. Once there, approximately 30 scheduled and chartered services fly between cities and remote camps.

Fact

Yellowknife owes its existence to the discovery of gold here in 1934. Named after the copper knives of the local Indians, the city became capital of N.W.T. in 1967.

The N.W.T. has conventional highways too, which connect the majority of the large communities, including Yellowknife 1 [map], Hay River, Fort Smith, Inuvik, and Fort Simpson, with the outside world. These highways are all hardpacked gravel, rather than paved, so some adjustment to your driving style may be necessary. Yellowknife is also connected to Edmonton by a regular “black top” (asphalt) road.

Owing to a distinct lack of vehicular traffic, travel in the Territories can indeed be a relaxing experience and a great relief to those more accustomed to aggressive city driving. Drivers will see few vehicles on the roads, and are likely to see more wildlife than vehicles along the way. The Dempster Highway places restrictions on travel during fall and spring while herds of caribou, numbering in the tens of thousands, make their annual migration.

The Western Arctic

In all the territory west of Great Slave and Great Bear Lake up toward Inuvik – the Western Arctic – there are numerous equipment stores in the major communities. Below the tree line, canoe trips take place from late May to mid-September. In the tundra area most trips take place from mid-June to mid-August. In recent years, cross-country skiing trips have been set up during the spring so that tourists can witness the spectacular migration of caribou herds in style. Participants are flown into a base camp, and from there they glide onto frozen lakes and rivers to observe the caribou migration.

A frosty musk ox.

Getty Images

Domain of the bison

In the southern region of N.W.T. there are two spectacular national parks. Wood Buffalo National Park 2 [map] is located on either side of the Alberta–N.W.T. border and was established in 1922 to preserve the bison. This objective has been a success, and one can now attend a “Bison Creep” to view these creatures. Occupying an area roughly the size of Switzerland, the national park covers a remarkable landscape of forests, meadows, sinkholes, and an unusual salt plain.

The second national park, further to the west, is located in the remote southwest corner of the territory on the Yukon border. Nahanni National Park 3 [map], which is a Unesco World Heritage Site, is in the Deh Cho Region, also known as the Nahanni-Ram. The region was once home to a mysterious people called Nahaa or Nahannis. Legends of wild mountain men, a white queen, evil spirits, lost maps, lost gold, and headless men are myths that prevail to this day.

Bird enthusiasts are one group that hasn’t been deterred from venturing into the Deh Cho. In addition to seeing such exciting birds as white pelicans, peregrine falcons, and trumpeter swans, there are impressive river gorges, underground caves, and bubbling hot springs. The adventurous can take an exciting river-rafting trip down the South Nahanni river, one of the wildest rivers in Canada. Access to the park is by air only, from Fort Simpson 4 [map].

Culture in Yellowknife

Yellowknife now promotes itself as “the diamond capital of North America,” not only because of its proximity to the only commercial diamond mines on the continent, but because of the dazzling scenery that surrounds it. Overlooking Frame Lake in the center of town is the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre (museum daily 10.30am–5pm, Thu until 9pm; www.pwnhc.ca; free), which houses excellent histories and artifacts of the Inuit, Dene, and Métis.

Tip

Yellowknife has one of the N.W.T.’s few golf courses. However, the only course with grass greens (rather than sand) is at Hay River, on the southern shore of the Great Slave Lake.

A unique experience

Much of the Northwest Territories is completely untouched by civilization. Here, the traveler sees first and foremost the land and how the plants and animals here have adapted to their environment. The impact of humans on this land has been minimal, allowing its delicate balance to survive. The impressive mountains, the barren grounds, the stunted forests, the overarching skies, the thousands of freshwater lakes and rivers of this vast land combine to create a unique and humbling experience.

Spectacular Hood River.

Getty Images