Jeff Greenwell

YOU DON’T ACTUALLY HAVE TO QUIT YOUR JOB FOR THESE ADVENTURES—but they do take enough of a time commitment that you might want to give your boss a heads-up a few months (or a year) in advance. On the other hand, these trips are long enough that, halfway through them, you will definitely find yourself wondering if you really do need to go back to your job when the adventure is over. A few weeks in the bottom of the Grand Canyon without access to e-mail, for example, can change your perspective. So can six weeks on the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route. If you’re lucky enough, or diplomatic enough, to be able to get this much time off work and in nature, you might find yourself with a big shift on your life perspective by the end of your trip—which is kind of the whole point on doing a big thing, isn’t it?

Mike Deme

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: If you’ve ever thought about riding your bicycle across America but weren’t in love with the idea of sharing the road with hundreds of cars, the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route might be for you. Rolling along the Continental Divide, the route begins in Banff, Alberta, Canada, and finishes in Antelope Wells, New Mexico (on the US–Mexico border), covering 2,768 miles of terrain, most of it unpaved.

On the route, you’ll cross the Continental Divide 30 times and climb more than 200,000 feet. It’s 90 percent unpaved, mostly dirt roads with a small amount of single-track, as it runs through Alberta, British Columbia, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico. It’s not only a challenge of endurance but also of route finding—it’s not officially signed, and at times, you’ll go more than 100 miles between water and food sources. Oh, and you might see the occasional bear—but maybe just pronghorn and antelope.

Participants in the Tour Divide race start their attempts in mid-June of each year and finish in 2 to 3 weeks—which requires pedaling more than 125 miles per day. To ride the route at a more leisurely pace (and have time to take more photos), plan on at least 6 weeks (and add a little extra time to get yourself and your bike to and from the start and end points). You’ll need a reliable mountain bike or cyclocross bike, bike-packing bags or a trailer, some solid bike maintenance/repair knowledge in case of minor mechanical problems in the middle of nowhere, and the fortitude for some long days in the saddle.

SEASON: Late June–Sept

INFO: adventurecycling.org

© iStock.com/tonda

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: Millions of people visit the Grand Canyon each year, but most see it only from viewpoints on the South Rim—and only 10,000 people each year get to see it from the bottom of the canyon, on the seat of a nonmotorized boat. The difference? Many visitors spend only a few minutes at the South Rim, and seeing it from the bottom on a boat takes anywhere from 12 to 28 days. Oh, and most people who have been on a Grand Canyon raft trip will probably tell you it was an experience of a lifetime—luxury beach camping, 277 miles of river travel with more than 40 rapids rated 5 or higher on the Grand Canyon’s own 1–10 whitewater rating scale, millions of years of geological history, and no cell phone signal (that’s right).

Most guided Grand Canyon boat trips take between 12 and 16 days and run April through October. Every day, you’ll ride on a raft or a wooden dory rowed by a skilled guide, who will ideally keep the boat from flipping in all those rapids (which they usually do, but there are no guarantees), and you’ll stop to hike up some of the dozens of side canyons that line the Grand. Every night, you’ll have dinner and drink and sleep under the stars on a beach on the riverbank as the Colorado flows by. At the take-out, you’ll very likely think it was the best camping trip you’ve ever had.

SEASON: Apr–Oct

INFO: oars.com/grandcanyon

YOU PROBABLY FEEL LIKE YOU’RE PULLED in a million different directions: Work, family, home maintenance/improvement, yard work—the list never ends. Even if we don’t have a lot of commitments, a lot of us find it difficult to take time off work (Americans are statistically very bad at it). So it’s hard to look at an adventure and tell yourself you deserve a few weeks, a week, or even just a weekend off to go do something in the wilderness.

But listen when I tell you that you need something to put in your end-of-year holiday cards. If you don’t send cards, you need something to look back on at the end of the year—besides all those commitments in life. It’s great to do your job and keep the gutters clean and the yard trimmed, but no one gets to the end of their year and says, “Wow, what a great year—I mowed my lawn every Saturday like clockwork!” Plenty of folks do, however, look back at photos of their hikes, weekend trips to new cities, and vacations and smile.

You have to first convince yourself you are worth it and then follow through with everyone else in your life. In many circles, this is called “self-care”: the idea that we need to take care of ourselves in order to lead productive lives. Usually, self-care deals with sleep, nutrition, and exercise, but plenty of people will tell you that getting out of your routine is a part of self-care as well. To me, that means having an adventure, whether it’s for a day or a month. (Let’s be honest: Most of us can envision taking a day off more than a month off.)

So talk yourself into it first. It may be setting aside a couple of weekends each summer for your own adventure dreams, taking a Friday off to travel somewhere new for the weekend, or taking a Tuesday off to go skiing or hiking. Yes, you might get paid for those unused vacation days at the end of the year, but there are few things that you can buy with that money that are worth getting out of the office instead. It’s easy to get stuck in a rut where you’re working hard for everyone else and neglecting the things you want and need—like spending the night sleeping under the stars or going for a long hike—so you have to recognize it and schedule some time out of the rut for yourself.

Now I know you’re important at work and at home, but trust me, the folks at work and at home can do without you for a day or a couple days. Although it’s tough to imagine, one day the world will keep going on without you in it and will do so for many years. You’d be surprised what people do when you’re unavailable for a day or two: They figure it out on their own. Yes, if you were there, you could have helped (or maybe even done it better), but don’t think about that. Think about self-care and schedule some time for yourself.

© iStock.com/wildnerpix

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: Do you like backpacking? Then you’ll love the Appalachian Trail, the longest hiking-only trail in the world, which offers prospective suitors 2,190 miles of hiking from Springer Mountain, Georgia, to the summit of Mount Katahdin in Maine. That’s about 5 million boot-steps, which takes most thru-hikers 6 months to complete. To hike the entire trail, you have to quit your job, already be unemployed, or be really good at taking conference calls while huffing and puffing your way up the next hill, carrying everything you need in your backpack.

The good news is walking every day for 6 months will probably get you in the best physical shape of your life. Oh, and the scenery of one of the world’s oldest mountain ranges isn’t half bad, if you enjoy rushing creeks as well as mountainsides and valleys packed with deciduous and evergreen trees. And you’ll have company: Around 2,500 to 3,000 hikers start the Appalachian Trail each year, but only one in four hikers finishes. Injuries are a common reason for ending a thru-hike, as is running out of money—most hikers will spend $1,000 per month on the trail.

The United States now has three long-distance trails running north to south, including the Pacific Crest Trail on the West Coast and the Continental Divide Trail through the Rocky Mountains—but the original is the Appalachian Trail, conceived in 1921 and completed in 1937 (and first thru-hiked in 1936, before it was finished).

SEASON: Apr–Oct

INFO: appalachiantrail.org

© iStock.com/UT07

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: After Cheryl Strayed wrote her best-selling book Wild about her trek on the Pacific Crest Trail (not to mention the 2014 movie of the same name starring Reese Witherspoon), the PCT rose to prominence alongside its older, more established sister trail, the Appalachian Trail.

The trails are similar in that they require tremendous amounts of time and effort—most people take 6 months to hike the PCT or the AT, carrying everything they need in a backpack. But the scenery on the PCT is far different from that of the AT: The PCT begins in the Southern California desert, then climbs into the clean granite of the Sierra Nevada (home to the highest mountain in the Lower 48, 14,505-foot Mount Whitney), then into the deep forests of the Pacific Northwest in Oregon and Washington. PCT thru-hikers often use mountaineering axes to cross snowfields in the Sierra, camp in the wild almost every night, and cross large swaths of desert between water sources. Over its 2,659 miles, the PCT takes hikers up to elevations of 13,153 feet and as low as barely above sea level.

Some thru-hikers don’t have to choose which long-distance trail they want to experience—once they have been bitten by the bug on the AT, the PCT, or the Continental Divide Trail, they tackle the others and complete America’s Triple Crown. This, of course, requires three summers for most people and also seasonal employment, a liberal vacation policy, or a very understanding boss at work. But if you’re going to go on a backpacking trip, why not go on a big one?

SEASON: Late Apr–Sept

INFO: pcta.org

VERY EARLY IN MY LIFE OF EXPLORING THE OUTDOORS, I worked at an outdoor shop. I was excited about hiking and backpacking and climbing nontechnical mountains. But my coworkers were set on taking me rock climbing. I wasn’t having any of it. I gave them excuses: No thanks, I’m not some sort of adrenaline junkie, or I’m scared of heights, or I’m just fine hiking in beautiful places.

Finally, I relented and went climbing with them one day. It was just like I thought it would be: terrifying. I hated it. I went a handful of times and never got comfortable, and then I packed away my climbing shoes and harness for a year while I did other things in the outdoors. A year later, I tried climbing again, and something about it took this time. I liked it. Was I still scared of heights? Hell yes. Was it debilitating? Not quite.

A decade later, I had climbed all over the West and Europe, pushing myself to deal with fear in some very real situations. I became comfortable standing on cliff edges hundreds of feet off the ground. I was aware of heights but less afraid of them. I was functioning instead of shaking and hyperventilating. Instead of backing away from something I was scared of, I went to it to learn how to manage fear.

I believe adventure can be dealt with the same way. Lots of things are scary the first time: sleeping in a tent (what about bears?), going hiking (what about lightning?), or traveling to a new country (will anyone understand me?). You can live in fear of everything and never go outside, or you can go see for yourself what it’s like. Most of the time, I believe people tackle things they are anxious about and afterward say to themselves, “Well, that wasn’t so bad after all.”

I think everyone exists on a spectrum of adventure from “Not Adventurous at All” (i.e., never doing anything out of our daily routine) to “Extremely Adventurous” (i.e., war reporter, climbing K2 in winter). I think with every new thing we try, we push ourselves a little more toward the “Extremely Adventurous” end of the spectrum, collecting “That Wasn’t So Bad After All” experiences along the way—not to mention collecting some wonderful memories of new places, new people, and new things we learn about ourselves. I personally used my rock climbing experiences to deal with a fear of public speaking (something many people share): I told myself I had done many things without certain outcomes before and survived, so why should public speaking be any different? It took about a dozen experiences before I was comfortable going up in front of a group of people and telling my stories, but just like rock climbing, exposure lessened the anxiety.

You don’t have to become a rock climber, war reporter, or climb K2 in the winter to experience the joy of new adventures. You just have to start with something you’re a little scared of. Maybe it’s traveling to the Galapagos Islands, trying mountain biking for the first time, or finally asking your boss for 3 straight weeks of vacation so you can hike the John Muir Trail. Whatever it is, trying something you’re curious about (but also worried about) can be incredibly rewarding and can open you up to even more new experiences.

© iStock.com/1111IESPDJ

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: If you visit Alaska with hopes of seeing Denali, the highest summit in North America, you might hear from locals that on any given summer day, your chances of seeing the mountain are about 50-50. It’s so big, it creates its own weather, so it’s often hidden behind a cloud. Seeing it is hard enough, and climbing it is no walk in the park—only a few hundred people get to the summit each year.

Denali’s 20,320-foot summit doesn’t come easily—or quickly. You’ll need about 3 weeks off work just to attempt the climb, including flying to Alaska, getting flown to the Kahiltna Glacier where the climb begins, and then several days of hiking gear higher up the mountain and waiting for good weather to attempt a summit bid. And that’s not all—most guide services won’t take clients on Denali if they haven’t had at least some mountaineering experience. Guides will require climbers to have mountaineering skills, usually acquired through a multiday mountaineering field seminar or a guided climb of a peak like Mount Rainier.

The good news is, the climb itself isn’t that technical—just snow climbing and lots of travel on snow to get to the climbing. You’ll climb to the top of one of the most famous peaks in the world and have views unlike anywhere else. Denali is the third most prominent and third most isolated mountain on earth behind Mount Everest and Argentina’s Mount Aconcagua, meaning it doesn’t have very many high mountains as neighbors. Beautiful, yes, but not nearly as high, so once you’re on top of Denali, the views don’t quit.

SEASON: May–June

INFO: climbalaska.org

Rachel Stevens

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: Traveling at 11 mph by bicycle is the perfect speed: slower than a car, which blows by everything at 65 mph or more, but way faster than walking. And, there’s coasting downhill. You don’t use any fuel other than all the food you have to put in your body (which is tasty). If you want to see the United States of America—while getting some exercise—bicycling is the way to do it.

There’s no one set way to bicycle across the states, but the Adventure Cycling Association’s TransAmerica Trail was the first bicycle touring route to cross the country, mapped and finished in 1976. It’s 4,228 miles, and usually takes cyclists around 2.5 months to complete (if you do the math, that’s an average of 56 miles a day if you ride every single day for 75 days). But there’s no set time limit, of course, and many cyclists take longer to do it. You can carry all your gear with you and camp the entire way, carry minimal gear and stay in hotels every night, or even have a friend or spouse drive a support vehicle and meet you every evening.

On the TransAmerica Trail, you’ll start in Astoria, Oregon, on the coast of the Pacific Ocean, and end in Yorktown, Virginia, riding mostly rural two-lane highways the entire way. You’ll ride through Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks, pass Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, and ride part of the Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia on your way to the East Coast. Touring cyclists usually burn 4,000 to 8,000 calories per day, so be prepared to eat lots of pie along the way.

SEASON: May–Sept

INFO: adventurecycling.org

1.BRING YOUR OWN FOOD. Yes, this sounds like an obvious idea, but many of us forget it. How many times have you been hungry on the road, searched for a restaurant, settled for something that wasn’t that great, and then wished (even just a little bit) that you hadn’t spent $25–30 on an underwhelming meal? I don’t know about you, but I haven’t been that disappointed in many of the sandwiches I’ve made for myself, and I certainly never get the feeling that I didn’t get my money’s worth.

2.BRING A FORK, SPOON, AND BOWL WITH YOU AND KEEP THEM HANDY. Someone once told me the first rule of being a dirtbag is “Always have a spoon,” so you never miss out on free food. Having eating utensils with you means you don’t have to rely on convenience foods, which are usually expensive and not that healthy for you. If you have a fork, you can pop into a grocery store and make yourself a salad in the parking lot. If you have a spoon, you can make yourself a peanut butter and jelly sandwich in the same parking lot. And so on.

3.DON’T SHOWER EVERY DAY. In real life, showers are necessary to not offend your coworkers, friends, and family. On the road, they’re a luxury and can be pretty costly. Think about it: If you need to shower every day, you need to get a hotel almost every single night, and that’s (in a very inexpensive hotel) at least $65 per day. If you find public showers somewhere (at a rec center or a campground), they’re more like $5–10 but can still put a major hitch in your day. Learn to be low-maintenance and you’ll be more efficient and save money. In years of road-tripping around the West, I’ve discovered that taking a shower every few days and doing a little triage in between showers is just fine and keeps the focus where it should be: on having fun and seeing as much as possible.

4.LEARN TO STAY IN A TENT INSTEAD OF A HOTEL. You can grab a tent spot at most campgrounds for $20 or less. Traveling in a car or truck and sleeping in a tent is way cheaper than the alternatives of hotels (finding a new home every night) or RVs (bringing your home with you everywhere, paying for way more gas, and paying more for hookups).

5.DON’T PAY FOR WATER. That’s right. Buying bottled water is not only terrible for the environment, but it’s also ridiculously expensive. There’s enough free water out there that you should almost never have to pay for it. Just buy a few 1-gallon jugs of water ($1.35 each at any grocery store), and keep them with you to refill when you’re traveling and camping. Once you start looking, you’ll have no trouble finding the free water spigots at campgrounds, national parks, tourist town visitor centers, and even truck stops along the interstate. And you won’t be throwing away dozens of plastic bottles throughout your trip.

© iStock.com/LyleRussell

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: If it weren’t for a Scottish immigrant named John Muir who spent all his spare time falling in love with nature and writing about it in the late 1800s and early 1900s, we might not know California’s Sierra Nevada as the “Range of Light.” His namesake trail in the Sierra is a backpacker’s life-list trip, a 211-mile tour of the clean granite peaks and alpine lakes that he made famous in his writings.

The JMT is no beginner’s trek, with 47,000 feet of cumulative elevation gain and 3 weeks of daily hiking while carrying everything you need on your back. You won’t have to carry all your food and fuel for the entire 3 weeks at once—there are several resupply points along the way where you can ship your food and fuel in advance.

On a thru-hike of the JMT, you’ll cross eight high mountain passes, stand on two iconic summits (Half Dome and Mount Whitney), and walk through three national parks: Sequoia, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite. Almost all of the trail is in wilderness, and about a third of it is above 10,000 feet. But the scenery is some of the most beautiful—and famous—in the Lower 48. A thru-hike of the JMT is an unforgettable experience and much more manageable than a 6-month thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail.

SEASON: July–Sept

INFO: johnmuirtrail.org

Christina Fawn

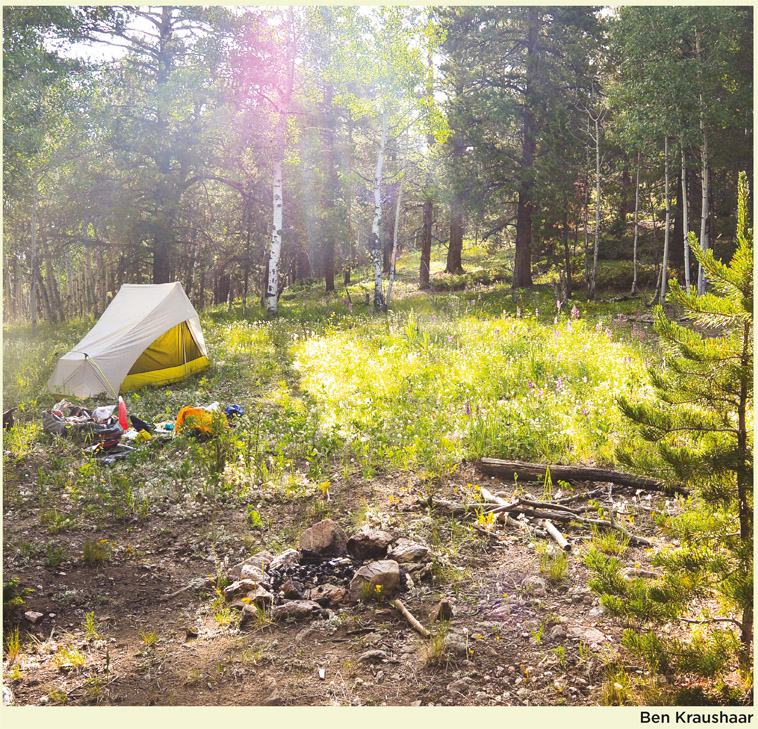

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: If you haven’t spent much time there, you might not know how different the mountains in Colorado’s Front Range are from the San Juans in southwest Colorado—but the Colorado Trail is designed to show you just that, from the rolling ridgelines on the eastern side of the Continental Divide near Denver to the rugged pinnacles of the San Juans in the historic mining country around Silverton and Durango, almost 500 trail miles away.

The 488-mile trail crosses eight mountain ranges and five river systems on its way across the state, beginning just outside of Denver in the foothills and ending in the town of Durango. The total elevation gain for a thru-hike is about 89,000 feet, or roughly three Mount Everests stacked on top of each other. The average elevation of the trail is 10,347 feet, although there are plenty of dips below treeline to offer shelter from Colorado’s infamous afternoon mountain thunderstorms. You won’t be carrying all your food for 5 weeks, as the trail passes through plenty of small towns where you can pick up resupply packages you’ve mailed to yourself. There are also plenty of opportunities to hitchhike or take buses into towns with hotels and grocery stores.

Most hikers take 4 to 6 weeks to complete the trail during the summer months (which makes it perfect if you’re an education professional with summers off), so it’s not quite as huge a commitment as the Appalachian Trail or the Pacific Crest Trail, but it is long enough to be the hike of a lifetime.

SEASON: July–late Sept

INFO: coloradotrail.org

THERE’S A SAYING THAT’S OFTEN ATTRIBUTED to Yvon Chouinard: “The more you know, the less you need.” Chouinard wasn’t the first person to say that, but all his years of climbing and mountaineering have likely taught him that. Climbers who are less sure of their skills or the climb ahead might take way more protective gear than is necessary (I know I have). Eventually, as climbers become more confident in their skills, they will trim down the amount of gear they carry up a climb, thus making the climber lighter in weight and more efficient (and less fatigued at the top of the climb).

The same is true for hiking, backpacking, traveling to a new country, air travel, or any sort of adventure. Every new experience is a chance for you to analyze what you took with you, what you used, and what you didn’t and then pare down your gear or luggage for next time.

Traveling light, in any form, can be its own luxury. Think about it: Would you rather carry a 40-pound backpack or a 30-pound backpack? Would you rather deal with a huge, unwieldy rolling suitcase on a train trip around Europe or a small bag you can easily lift into overhead baggage compartments? Simplifying your packing list can eliminate a significant amount of stress from a trip or outdoor adventure. Sure, you would love to have four pairs of shoes on your trip, but if you only brought two, you might be able to take a smaller suitcase. Same with clothes—how many outfits do you really need? Can you find a place to do laundry somewhere in the middle of your trip and cut your clothing list in half? Can you wear the same things two or three days of your trip instead of just once? Probably.

Very experienced backpackers focus on cutting weight and bulk wherever they can and often start long trips with a base backpack weight (not including food and water) of less than 10 pounds, which is incredibly light when you consider most backpacking tents often weigh 4 or 5 pounds on their own. But again, experience plus frequently analyzing what you need and what you don’t need pays off—especially on the first day of that backpacking trip when hikers hoist their packs onto their shoulders for the first time and start walking under their weight. It’s a far different trip to start when you feel crushed by your backpack than when it feels light.

It may not be for everyone—we all have certain creature comforts we think we can’t live without. But do you need all of them on the same trip? It might be worth thinking about. Learn to live with a little less next time and a little less the next time, and so on until you’re pared down to the essentials, just to see how it feels. Who knows—you might actually find that you like going “light and fast,” whether it’s on the trail or on a long weekend trip somewhere.

© iStock.com/blyjak

LENGTH: Quit Your Job

DESCRIPTION: Plenty of countries in the world have beautiful mountains—just none as big as the Himalayas. If you’ve ever been curious about what it’s like to wander around the true giants of our planet, the 20,000-plus-foot-tall glaciated peaks with avalanches ripping down their flanks, the Annapurna Circuit might be for you.

Most trekkers take 14 to 25 days to walk the 145-mile length of the circuit, starting in either Besi Sahar or Pokhara (each town a few hours’ drive from Kathmandu) and hiking to altitudes of up to 17,769 feet on their way around the Annapurna Massif. That’s right, the mountain is so big, it takes weeks to walk around it. From many vantage points on the route, you’ll be able to see some of the highest peaks in the world, several of them over 26,000 feet (that’s 11,000 feet higher than California’s Mount Whitney, for comparison).

Camping is not necessary on the Annapurna Circuit, thanks to the local network of trekker-friendly teahouses, where you’ll sleep and dine on Nepalese fare like dal bhat and yak butter tea. Of course, not taking camping gear and food means one other big plus for the trek: You don’t have to carry a big, heavy backpack. The route is not difficult to follow, but hiring a guide service to lead you on your trek is affordable and takes the guesswork out of reserving nights at teahouses. Several options now exist to cut down on walking mileage by driving some parts of the route—but if you’re taking 2 weeks to fly halfway across the world, why not take 3 or 4?

SEASON: Year-round

INFO: nepaltrekkinginfo.com