Chris Shane

WITH A WEEK, YOU CAN SEE A LOT OF A COUNTRY— even one as big as the United States, as two of the trips in this chapter prove. You can take an Amtrak train across the US, drive the entire Pacific Coast, climb Mount Rainier or El Capitan, or trek somewhere like Machu Picchu or the Routeburn Track in New Zealand. Not all of these adventures take seven days to complete—some are three or four days out in the field. That doesn’t seem like a huge time commitment for a memory of a lifetime, like standing on top of Rainier or hanging off the side of El Capitan, but it really is all you need. Caveat: You also need to train a lot for things like climbing Mount Rainier or El Capitan. But you don’t need to train at all to drive the Pacific Coast or ride an Amtrak train from New York to Los Angeles.

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: It’s no Trans-Siberian Railroad, but it might be one of the easiest ways to see the United States from Pacific to Atlantic: Riding a train with a sleeper car from coast to coast takes less than 4 days. Sound like a lot? If you hopped in a car in New York and drove 8 hours a day, it would take you 5.5 days to get to San Francisco. Of course, a direct flight is way faster, but that’s not the point.

Unless you live on one of the coasts, though, you will have to fly to your starting point and home from your end point, so keep that in mind when planning. Amtrak trains start in Los Angeles and San Diego on the West Coast, if you absolutely have to start in a city that touches the ocean. If not, you can start in Portland, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; Vancouver, B.C., or Emeryville, California (outside San Francisco). On the East Coast, you can start in Miami, Florida; Newport News, Virginia; New York; Boston, Massachusetts; and Portland, Maine. Costs vary according to your route, but if you have a travel partner and share your sleeper car room, it’s cheaper. All meals are included while you’re on the train (you’ll eat in the dining car for breakfast, lunch, and dinner).

You will have (or be able to schedule) layovers in different cities along your route, so plan accordingly if you’d like some time to explore. One thing to consider: When traveling west to east, set your watch back an hour every time you change time zones. Because of the speed of travel, you’ll only cross into one new time zone each day, so it can be a bit like “falling back” during Daylight Saving Time. If traveling from east to west, you’re “gaining an hour” every time you switch time zones on the train.

SEASON: Any season

INFO: amtrak.com

IT’S EASY TO WALK INTO A GEAR STORE and be completely bewildered by all the stuff on the walls or wonder if you should just buy everything they have so you can get started doing things in the outdoors. Calm down. You don’t need to buy everything. If you want to get started doing things in the outdoors but don’t know where to begin buying gear, here are a few things I’d put on my shopping list if I were starting all over again at zero gear. Hopefully, it will help you sort through all that stuff in the gear store and guide you to what you really need to get started. Obviously, gear companies would love to have you buy everything they sell, but truthfully, a good foundation of stuff can get you going on plenty of adventures. Lots of these things can be found used on eBay or at gear consignment shops.

1. 30-LITER BACKPACK. A 30-liter pack is a good size for lots of single-day activities—day hikes, ski resort days, peak bagging, hauling books/laptops to the office or across campus, bike commuting, picnicking, whatever. If you’re buying one backpack for all your one-day activities, 30 liters is a great size. A bajillion people make 30-liter packs (or 28-liter or 32-liter), and you can find them all over the Internet.

2. LIGHTWEIGHT SOFT-SHELL JACKET. A solid lightweight, breathable, soft-shell jacket should be a go-to layer for spring and summer (or higher-altitude) mountain bike rides, trail runs, multipitch rock climbs, peak bagging, day hikes, or anything where you might get a stiff, cool breeze when you’re a little sweaty or exposed to some wind and possibly a little rain.

3. 60-LITER BACKPACK. A 60-liter pack isn’t the biggest you can buy, but most of us aren’t going on backpacking trips longer than 7 days often enough to justify owning anything much bigger than that. I think 60 liters is perfect for 3-day or 4-day trips when you want to pack heavy, multiday climbs of peaks like Mount Shasta or Mount Rainier, as a piece of checked luggage for most things I do (which don’t often—actually, ever—involve clothes on hangers), 7-day backpacking trips when you don’t want to be carrying a bunch of extra crap anyway, and days of extreme luxury at the climbing crag. You should get a pack that fits you first and worry about features later (in my opinion).

4. HEADLAMP. If you go camping, backpacking, need to find things under your fridge, do car repairs on the street in front of your apartment, have permanently shut off your car’s interior light because of your tendency to leave it on and find a dead battery the next time you try to start your car, a headlamp is for you. You can spend $400 on one that will illuminate a mountain bike trail at 20 mph (useful for those times you find yourself needing lighting while traveling at high speeds), or you can spend $19.95 and get a basic one (useful for everything but lighting while traveling at high speeds). I’ve always preferred simple, minimalist lights that run on small batteries and don’t light up a million yards away from you or have a bunch of functions that you have to tap Morse codes on the power button to operate. I never leave the trailhead without a headlamp stuffed in my pack somewhere, and that’s prevented a few nights of sitting on a rock in the dark waiting for the sun to come up again.

5. WATER BOTTLES. To paraphrase Ian MacKaye, companies are not selling you water; they’re selling you a plastic bottle. Water is free. If you have a water bottle, you can access and store water so you can take it with you when you walk away from the source, such as an airport drinking fountain. With a full water bottle or two, you have some chance of actually staying hydrated on a trans-Atlantic flight, since you don’t have to rely on flight attendants pouring you a 4-ounce cup of bottled water every 3 hours.

6. TRAIL RUNNING SHOES. Something they don’t tell you about running shoes: You can just walk in them if you don’t want to run. In fact, it’s often less strenuous than running. You can wear trail running shoes for hiking and backpacking, as long as you can live without the ankle support and stout outsole of hiking boots. You can also use trail running shoes to run on surfaces other than trails. I wouldn’t stop anyone from buying a pair of hiking boots, but if you have room for only one pair of outdoor shoes in your luggage, trail running shoes are probably more versatile.

7. RAIN SHELL. If you go out there, you’re going to get rained on sometime. There are tons of different models available, and generally, the more expensive they are, the more breathable they are (that money is spent on the technology in the jacket, and everyone’s trying to make a lightweight, breathable, waterproof jacket). Get something that says “waterproof” that’s in your price range, and you’ll be happy. If you’d like a super-packable ultralight one to take for “just in case” showers, there are plenty of those available in the $125–150 range.

8. PUFFY JACKET. Pros: super-warm, compresses down to nothing in your backpack, can be used as a pillow. Cons: rips easily, doesn’t insulate when wet (unless it’s synthetic insulation or treated down), easily perforated by flying sparks from campfires. Be good to your puffy jacket and it will be good to you. It’s like an appetizer for the later, full meal of getting into your sleeping bag. It can be your happy place. I have always used small amounts of Krazy Glue to patch the little holes in my puffy jackets, but most people use duct tape.

9. TWO-PERSON BACKPACKING TENT. If you want to buy a bunch of tents for all your needs, you could get a one-person tent for all your solo backpacking (or bike-packing) trips, a two-person tent for trips you take with a friend, a big car-camping tent for weekends when you go out with friends and want to spread out all your stuff and maybe just stand up inside your tent because you can. Or you could just buy a basic two-person backpacking tent and use it for everything—including not taking up as much space as three separate tents in your gear closet/garage.

10. 15°F SLEEPING BAG. I’ve done most of my camping and backpacking in the past decade in the mountains and desert of the West, and I’ve never found a 15°F sleeping bag to be overkill. Only in rare, way-late-season situations has it proven to be too chilly. If you’re a very cold sleeper or are planning on winter camping, a bag with a rating closer to 0°F is probably more appropriate, but I would say most people buy something moderate (15°F or 20°F rating) and then buy a different sleeping bag for winter so they’re not hauling around the extra weight of a winter bag all year. A 15°F or 20°F sleeping bag is a great all-purpose, three-season sleeping bag. Down sleeping bags are more compressible and lighter but generally more expensive, and synthetic bags are bulkier but have traditionally held insulative value better when wet. Lots of companies are now using treated down, which has helped down insulate better when wet (and dry more quickly than untreated down). I haven’t had a ton of experiences where my sleeping bag has been completely saturated, but I have been very impressed with treated down in situations of extreme condensation (sleeping without a tent next to a river or another humid scenario) and picking up moisture from the inside of a wet tent or from wet clothes and gear during a rainy trip.

11. SLEEPING PAD. These pads are for sleeping on the ground. They’re not all the same, but they’re all better than sleeping on the actual ground. I can’t 100 percent recommend one particular model for super-cushy unpuncturable comfort, but I’ve never carried one that weighs more than 1.5 pounds.

12. ISOBUTANE (CANISTER FUEL) STOVE. Yes, Jetboils are exciting, efficient, and compact, but I think a solid (non-Jetboil) canister stove is a great entry point for anyone who’s getting started in the outdoors. I like Jetboils for certain applications, but cooking nondehydrated meals in a pot is not one of them. If you want to make your own pasta, grab a simple canister stove and a windscreen (if it doesn’t come with one, make one out of a foil turkey roasting pan from the grocery store) and get going.

Jessica Kelley

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: Guides and climbers who have spent time on the mountain will tell you Mount Rainier has everything a big mountain in Asia has—glacier, crevasses, seracs, and intense weather. But, you’ll probably notice that it’s a lot easier to get to than, say, Ama Dablam.

Rainier is visible from the city of Seattle on clear days, and even a guided ascent is a quick trip most people can fit into their schedules: 3.5 days total, including 1 day of learning how to walk in crampons, use an ice axe, and be an efficient member of a rope team. The climb of the trade route on the peak, Disappointment Cleaver, involves 9,000 vertical feet of snow climbing, broken into 2 days: On Day 1, climbers walk up the Muir Snowfield from the Paradise parking lot at 5,400 feet to Camp Muir, 10,188 feet. After going to bed early and spending a short night at Camp Muir, climbers leave the hut (or tents) at 1 or 2 a.m. on Day 2 to begin the summit day, a climb from Camp Muir to the 14,410-foot summit.

It’s a short time commitment, but a huge fitness test—there’s nothing that quite compares to hiking up steep inclines for that long on snow. But, with the right preparation (becoming good friends with the Stair-master, doing lunges, or running/walking flights of stairs) and a sizable amount of mental fortitude, it’s doable with very little mountaineering experience.

SEASON: June–Sept

INFO: rmiguides.com

LENGTH: Weeklong

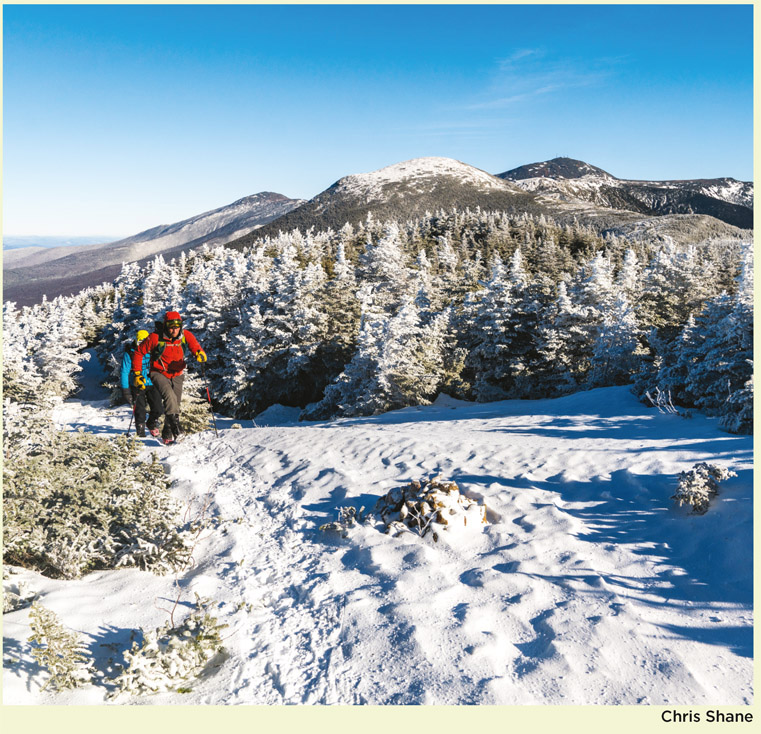

DESCRIPTION: New Hampshire’s Mount Washington is well known for having “the worst weather in the world.” It sits at the convergence of three storm paths, has seen wind speeds measuring up to 231 mph, and has had winter temperatures as low as –115°F. So it’s a great place to head for a winter hike, right?

If you’re looking for a full-on mountain adventure on the East Coast, a winter Presidential traverse is it. But it’s not to be taken lightly. It’s a 22-mile hike often necessitating snowshoes and crampons, covering 8,500 feet of elevation gain and at least 2 nights of camping out in cold conditions (most parties take 3 to 5 days to complete it during the winter). Sound like fun? There’s a reason it’s a mountaineering rite of passage in the Northeast: It’s tough.

After the first summit—Mount Madison—you’ve knocked out most of the elevation gain, but you’re then exposed to the elements on the high ridge for almost 12 miles. If you’re lucky (or just get a good weather forecast), you won’t get the high winds and freezing windchill the Presidential Range is famous for in winter, and you’ll tag the other seven Presidential summits without incident: Mounts Adams, Jefferson, Clay, Washington, Monroe, Eisenhower, and Pierce.

If a winter traverse isn’t your thing, a summer hike across the range is also a great way to see the range and doable in as little as a day (if you’re extremely fit and efficient). The weather can still change in an instant and be dangerous during the summer, so be prepared.

SEASON: Dec–Mar

INFO: mountainsenseguides.com

“NOTHING DRAWS A CROWD LIKE A CROWD,” goes the saying. We’ve all been there—sitting in traffic in a national park or sharing a famous photo destination with 200 of our closest friends, simultaneously thinking, “This place would be so great if it weren’t for all the people,” and, “I’m one of those 200 people.”

So how do you beat the crowds? One way is to go in the off-season. Every great place has a few months a year that are the most popular. If you want to see and be seen, by all means, go skiing over the Christmas holiday, go to Yosemite in the middle of the summer, and travel in the Alps in August (when most Europeans take their month-long holiday).

But if you’d rather not share someplace with “the crowds,” do a little research—when are the busy times? Is the weather still okay a few weeks before or after the high tourist season? Is there an open-and-shut case for not going to that place during the off-season, or do the pros still outweigh the cons?

It will pay off. You’ll make some sacrifices, whether it’s a less-predictable weather forecast, fewer restaurants open, or fewer lodging options. But it can be more affordable (plane tickets, hotels, and campgrounds costing less because of less demand), less crowded, and maybe more enjoyable.

For example, the desert Southwest, especially Moab, can be extremely busy during “Spring Break,” which seems to take up the entire month of March nowadays. Fall, especially October, can also be very busy. So what to do? How about the 4 weeks between November 15 and December 15? Yes, it’s cold at night, and the days are short, but there’s a lot you can accomplish between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m., especially when you’re not fighting thousands of other people for parking spots, backpacking permits, restaurant tables, and hotel rooms.

Lots of traffic to US national parks is families with children, and parents, of course, schedule their vacations during their kids’ summer break from classes. If you don’t have kids, it makes sense to plan your vacations to hot spots like Yellowstone National Park just after students go back to school in the early fall, when reservations are much easier to make.

I’ve been to Ireland in January, the Grand Canyon in December, and Telluride in May (after ski season ends and before most of the trails are dry from spring runoff). Every experience was made a little better just by the fact that we felt like we had the whole place to ourselves—even if a lot of the “tourist amenities” were closed for the off-season, and it was a little cold or a little rainy.

Of course, lots of places are popular at certain times for a reason, and it’s not a bad thing to be in those places during popular times—riding the mountain bike trails around Moab when it’s sunny and 72°F, for example. But if you go, be prepared to be patient and meet some new friends from all over the world.

© iStock.com/rickberk

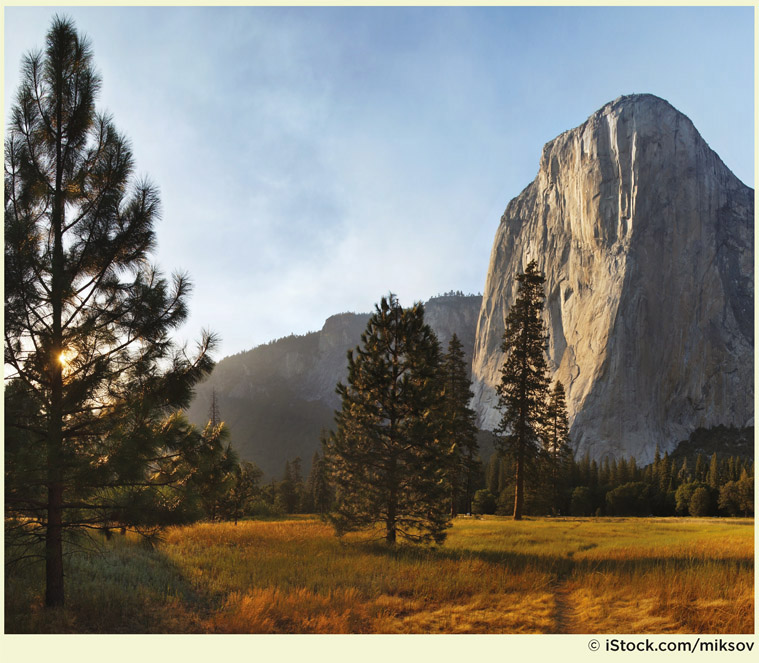

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: It’s the most famous rock wall in the world—a 3,000-foot-high sea of granite towering above the Yosemite Valley. Climbing it is on thousands of climbers’ life lists, and many never make it to the valley to attempt it. Those who do usually spend several days working their way up the wall, hauling everything they need with them—which includes climbing gear, camping gear, food, human waste (eww), and water (because there’s no water on El Cap unless it rains, and you don’t want it to rain up there).

And you don’t spend all your time just climbing up there. Ascents of El Cap involve long hours belaying, putting together and taking apart portaledges (those human-sized trays that attach to the wall to give climbers a flat surface to sleep on) every evening and morning, and managing life in a vertical environment (i.e., don’t drop anything). But the climbing is magnificent and plentiful. No matter what route you choose to climb to the top of El Cap, you’re climbing somewhere between 1,800 and 3,000 feet of some of the best granite in America (if not the world).

Only one company, Yosemite Mountaineering School & Guide Service, guides climbs of El Capitan, and if you’re interested, it’ll cost you $5,800 for a 6-day climb. But where else can you spend a week climbing granite without touching the ground?

SEASON: Apr–Oct

INFO: travelyosemite.com/things-to-do/rock-climbing

NPS/Neal Herbert

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: This is an epic mountain bike tour without carrying epic amounts of gear. That’s right, the preferred protocol for the 100-mile White Rim Trail through the Islands in the Sky District of Canyonlands National Park is to ride with Jeep (or truck) support and to take 3 to 4 days to do it. What does that mean for the mountain bikers? As much water as your support vehicle can carry, for one thing—and that means a lot on the White Rim, where there are no water sources. It also means you can take all kinds of heavy food and camping gear and a cooler full of beer if you want.

A vehicle to carry all your stuff is wonderful, but so is the scenery and the riding on the White Rim. It’s so named because of the layer of White Rim sandstone that forms the top of the cliffs above the Green River and Colorado River, where the road takes riders, weaving through a wonderland of red sandstone cliffs and geological formations. Riding is all on a four-wheel-drive road, so it’s not technical, but you ride about 1,000 vertical feet down to the road from above on your first day, so you have to pedal up that distance on your last day as well. Self-organized trips have to obtain camping permits through Canyonlands National Park. If you prefer a guide to handle logistics and permits, guided trips are available for about $900 per person.

SEASON: Sept–Oct, Mar–May

INFO: westernspirit.com

HERE’S A SITUATION YOU’LL FIND YOURSELF IN when going “off the grid” for a few days in the 21st century: You’re on your way to the place you’re going that doesn’t have cell phone service, whether it’s in the backcountry of Utah or Montana or the mountains in Nepal. You’re getting closer to the trailhead or getting ready for takeoff on an international flight, and you’re trying to catch up on those last bits of data that are coming through the Internet to you: one more check of Facebook, Insta-gram, and/or Twitter just to see if anything interesting has popped up in the past few minutes. One more check of your e-mail, even though you turned on your out-of-office autoresponder hours ago and anyone who matters already knows you’re going to be gone and not communicating for a few days or a couple weeks. One more text message to really close friends or family saying, “Talk to you when I get back!”

And then it happens, the moment we all secretly dread: We’re cut off from data for a few days or weeks. What if something happens? What if someone from work needs my expertise or opinion on something? What if one of the many people I follow on various social media platforms does something they’ve never done before? WHAT IF I MISS SOMETHING?

This feeling of anxiety may last a few minutes to a few hours until you reach that point of no return: You choose not to connect to the in-flight Wi-Fi because it’s so expensive, or you chose long ago to not activate your phone in whatever country you’re going to, or you’re so far in the backcountry that there’s no cell phone reception. Maybe you even check, just once, turning your phone off airplane mode, just to be sure there isn’t some 3G/LTE creeping through the mountains or canyon walls that will allow you to look at your Instagram feed. Or maybe you don’t at all.

After a day or two or three, you may notice something: that anxiety disappears and you don’t care that you don’t have data anymore. You focus on the things immediately in front of you, your experience on your trip, and taking photos of all the cool stuff you’re seeing. Maybe you brought a book, and you sit down to read that and realize you’ve forgotten how nice it is.

This feeling will last until near the end of your trip, when you start to feel a tinge of excitement: You will have access to data in a few hours. You can text, call, or e-mail loved ones to let them know your trip was fun and you are okay, maybe send a couple photos.

Maybe you dive right back into everything the moment you turn on your phone, frantically responding to e-mails and texts, scrolling through all the social media things that happened while you were offline. Or maybe you don’t do that, and you just let people know you’re alright before putting your phone back on airplane mode and enjoying the rest of your trip, finishing your book, or just absorbing all the great things about the place you’ve traveled to, and telling yourself it’s fine because you don’t have to be back in the office until Monday, and you’ll deal with all that stuff later.

© iStock.com/saiko3p

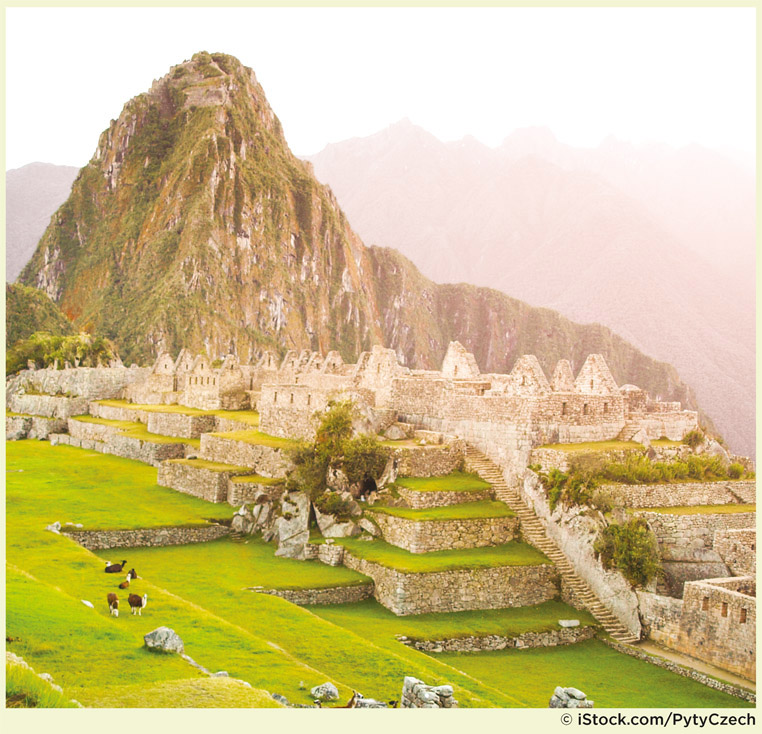

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: Since the “discovery” of the “Lost City of the Incas” in 1911, thousands of hikers have made the 4-day trek along the Inca Trail to the ruins of a city on the high saddle between the mountains of Machu Picchu and Huayna Picchu. The position of the city kept it safe from Spanish conquistadors, which also means it has incredible views looking into the valleys on the east and west. The architecture is pretty impressive as well: No one knows how the Inca people were able to move the large stones that make up the structures in the city that was home to an estimated 1,000 people in the 1400s and 1500s.

If you want to trek through the mountains to get to the famous view of Machu Picchu the same way the Inca people did, it’ll take 4 days and 3 nights. It’s not a particularly difficult hike, but it is 26 miles and at a fairly high altitude: The trail starts at about 8,500 feet in elevation and climbs to 13,780 feet at its highest point (Machu Picchu itself is at 7,972 feet). Don’t expect solitude: The trail is limited to 500 people per day, and permits are scooped up fast by trekkers from all over the world, so plan your trip well in advance.

SEASON: May–Sept

INFO: machupicchutrek.net

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: Fact: You can drive from Seattle, Washington, to San Diego, California, very efficiently on the inland I-5. Also a fact: You can take a week to drive from Seattle to San Diego on US 101 and SR 1, hugging the curves of the Pacific Coast and taking two-lane highways almost the entire way. If you decide to do that (highly recommended), give yourself a week or more to get it done. It’s about 1,600 miles, and if you drive 5 hours a day, not including stops for coffee, bathroom breaks, and lunch, it’ll take you almost exactly a week. If you want to stop anywhere cool, for example, to walk the beach in Olympic National Park in Washington, or check out the sea stacks in Cannon Beach, Oregon, or stare up at enormous trees 15 feet in diameter in Redwood National Park in California, or hike in Point Reyes National Seashore or in Muir Woods, or do anything in San Francisco or Los Angeles or San Diego . . . well, you get the point.

The two highways that transect the Pacific Coast combine for one of the most scenic drives in the entire country, with cliffs, beaches, dunes, and old-growth forests lining the road. You could take a month to explore everything along the route if you stopped often enough and had enough time to do it, but a week or so is the perfect amount of time for some car-based sightseeing. You’ll notice the coastal culture change as you drive south (or north) through three states, between urban and rural, from the sleepy coast towns of southern Oregon to the chaos of Los Angeles, and best of all, you don’t need a guide or any special skills to do it.

SEASON: Any season, but summer is best in Oregon and Washington

INFO: roadtripusa.com/pacific-coast

EVEN IF YOU’RE JUST GOING OUT FOR A SHORT DAY HIKE, lots of things can happen: a sprained ankle miles from the car, running out of water, running out of daylight, a shoe falling apart. Here are a few things I always carry with me, no matter what I’m doing, whether it’s a 5-mile hike or a 10-day backpacking trip.

• HEADLAMP. Have you ever hiked in the dark with no stars or moonlight? It’s an adventure for sure. I had a hell of a time finding my way back to the trailhead in the dark because the hike went longer than I thought it would twice in the span of about a month back in 2004. Guess what? It’s never happened again. I always take a compact, lightweight headlamp with me, no matter what I’m doing.

• SPACE BLANKET. This is a small package that looks like a fistful of aluminum foil, but it unfolds into a makeshift blanket that’s big enough to wrap a human being in like a giant burrito. What good is that? Well, it reflects your body heat back onto you and can help you survive an unplanned night out. Hopefully, you’ll never have to use it, but it’s 3 ounces of insurance that gives me peace of mind.

• DUCT TAPE. Everyone knows of the magical properties of duct tape, but you don’t have to take the whole roll with you in the backcountry. Just make a smaller roll of about 15 feet of tape (should be about 1 inch in diameter when you’re done), and throw that in your backpack. If the sole rips off your shoe, you’ll be happy you had that duct tape to fix it. Also good for blisters.

• BALING WIRE. A small amount of baling wire can be a lifesaver if you break a snowshoe in the backcountry, and it can repair lots of other things with a little imagination.

• PARACHUTE CORD. Fix a broken shoelace, rig a guyline on a tent, restrap a backpack shoulder strap, etc. Again, you don’t need 100 feet of it—but 15–20 feet is great.

• IODINE TABLETS. A small jar of iodine tablets weighs 3 ounces and can purify up to 25 liters of water. Why not have one with you at all times? That’s enough iodine to keep you pretty well hydrated for almost a week if something bad happens and you’re waiting for a rescue.

• LIGHTER. Yes, survivalists can start fires with no source of ignition. I can’t. I take a lighter, which takes 1 second to light.

• MULTITOOL. Doesn’t have to be expensive, doesn’t have to have a million tools on it. Mostly I end up cutting cheese with it, and sometimes doing the occasional repair.

© iStock.com/irisphoto2

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: There’s a reason the Routeburn Track is on almost every list of “best backpacking trips in the world”: pure mountain scenery—alpine valleys at your feet and striking, glaciated peaks above. That scenery is packed into a short trip: Most hikers take 3 days and 2 nights to cover the 32-km trail (that’s just under 20 miles, so not even 7 miles per day). Also, you’re not sleeping in a tent every night—camping is allowed, but hikers typically stay in Department of Conservation huts along the route. Okay, that’s actually three reasons. Regardless, if you need a reason to visit New Zealand, the Routeburn Track is as good as any.

With its short distance and challenging but moderate elevation gain, the Routeburn Track is within reach of anyone with good fitness and some hiking experience—you won’t be labeling it a “death march” for sure. The biggest challenge of the trek might be securing reservations in high season (Nov–Apr), when bookings are required for huts and campsites along the track. There are four huts and two campsites, and bookings for both fill up months in advance, so plan early. The Department of Conservation huts all have bunks, mattresses, heating, toilets, gas cook-tops, solar-powered lighting, and cold running water, but you’ll have to bring your own food to cook, cooking utensils, and sleeping bag.

It is possible to do the Routeburn Track outside of the high season, but flood and avalanche risks exist, huts are not staffed, and bridges may be out (and, obviously, it can be much colder!).

SEASON: Nov–Apr

INFO: doc.govt.nz/routeburntrack

Jason Zabriskie

LENGTH: Weeklong

DESCRIPTION: Imagine backpacking for 5 days, carrying everything you need with you, traversing a beautiful landscape, and sleeping under the stars every night. Okay, now imagine taking all that stuff out of your backpack, taking that heavy load off your shoulders and hips, putting it all in a lightweight boat, and instead of walking around that landscape, paddling that boat and gliding through water for 5 days.

Sold? Well, how about if we throw in some whale watching? Kayak touring is wonderful anywhere, but Washington’s San Juan Islands, the archipelago just north of Seattle, are one of the most famous sea kayaking destinations, and for good reason. Actually, there are a number of good reasons, including stable weather during the summer, forested beaches, the highest concentration of bald eagles in the Lower 48, sea otters, and, oh, no roads on any of the islands so no cars, thus, you can easily find solitude. And orcas (as previously mentioned) that you can view from water level.

Every day, you’ll paddle somewhere new, and every night, you’ll sleep somewhere else, making for a grand tour of one of the most interesting coastal ecosystems in North America. It’s a week of powering your own cruise ship—with way fewer people on board.

SEASON: May–Oct

INFO: sea-quest-kayak.com

ONE OF THE MAIN REASONS WE CITE for not traveling more is that we just don’t have the money. Traveling is expensive, and we just can’t seem to get ahead enough to make it work.

To boxsrrow a tactic out of my friend Alastair Humphreys’s book Grand Adventures, saving a little bit of money per week can add up to a fantastic trip once a year. I know everyone knows how to do math, but I also know a lot of us avoid it because we don’t like hearing the truth.

If you go out for a nice dinner once a week, you’re probably (conservatively) spending $25 just on yourself, including one entrée, a drink, and a tip. That’s $1,300 a year, or about what you might spend on a guided 3-day whitewater rafting trip through the Gates of Lodore in Colorado and Utah, including your flights.

Do you go through a bottle of wine or two every week at home? No, I’m not saying you have a problem, but one glass of not-that-expensive wine per evening adds up. One bottle of wine contains about six glasses of wine (and that’s if you pour exactly 5-ounce glasses), and one of those per night adds up to 60 bottles of wine per year. That’s $900 per year you’re spending on wine—if you only have one glass of wine every night (be honest)—which is about the cost of a round-trip flight from Chicago to Iceland.

If you take a coffee break from your office, grab a latte from the nearest coffee shop, and give the barista a decent tip, you’re spending $5 a day on coffee—or over the course of a work year, $1,250 on coffee, which is definitely enough to buy yourself a flight to Portland, a rental car, and a guided climb up Mount Hood.

Going out to dinner, drinking wine (or beer), and having coffee are all fun things. It all depends on what kind of fun you want to have in your life—if you want more adventure, sometimes the solution is less wine, or coffee, or that pasta dish you like at the Italian place near your apartment. But it can pay off with a summit sunrise on Mount Hood or getting splashed by the rapids in the Green River as you paddle through desert canyons.