© iStock.com/Bartfett

WHAT QUALIFIES AS A “FULL-DAY ADVENTURE”? For the purposes of this book, it’s an adventure that will probably be one of the biggest, if not the best, days you’ve ever had in the outdoors—mountain biking Moab’s 34-mile Whole Enchilada, hiking from the South Rim of the Grand Canyon to the bottom and then up to the North Rim (or vice versa), climbing a 14,000-foot peak in Colorado, or skiing Tuckerman Ravine in New Hampshire. These adventures don’t require spending the night sleeping on the ground (although you’re free to add that in if you’d like), but make lots of people’s bucket lists. They’re days that require some planning before and often a whole day (or more) to recover afterward, but will be one of (or some of) the most memorable days of your year, if you choose to take them on.

© iStock.com/irisphoto2

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: Colorado has 54 mountains with summits higher than 14,000 feet, and despite the “thin” air at the top, they’re not always that difficult to climb. In fact, many of them are Class 1 walk-ups, requiring no technical climbing skills or specialized equipment besides a sturdy pair of shoes and some extra food and clothing. Thousands of people from all over the United States travel to Colorado each summer and attempt one or more “14ers.” Although not as famous as the highest 14er in the Lower 48, Mount Whitney, many of Colorado’s 14ers are far more accessible—no permits are necessary, and some of the hikes are less than 10 miles round-trip.

The air up high contains less oxygen, so be prepared to slow down—often as you near the summit of a 14er, you’ll find yourself stopping every 5 or 10 steps to catch your breath before climbing higher. Add to that the fact that terrain up high might feel like a never-ending Stair-master. Even the easiest 14ers require more than 2,800 feet of elevation gain from the trailhead to the summit and hiking over and around boulders near the top.

The main precaution on a 14er: Leave early in the morning to allow yourself enough time to hike to the summit and back before afternoon thunderstorms roll in. It seems like there’s a thunderstorm every summer afternoon in Colorado, and above treeline on a 14er, there’s nowhere to hide. You need to be heading down from the summit by noon (if not before that), so plan on starting early and allowing yourself plenty of time to get up and down. It’s not a bad idea to do a headlamp start from the trailhead before sunrise.

SEASON: Mid-June–late Sept

INFO: 14ers.com

WHEN I WAS ON THE DENALI NATIONAL PARK BUS TOUR in Alaska several years ago, I met a retired firefighter from Lincoln, Nebraska, named Fred. Fred had driven all the way from Nebraska to Alaska, along the ALCAN, all by himself.

Fred said he camped out every other night on his trip and stayed in a hotel on the other nights. That way, he could have a shower and a bed every second night. I thought this was genius, not fully committing to either of the two opposing travel styles: those who must stay in a bed every night and those who must camp every night. Fred was cutting his trip costs probably in half just by carrying a sleeping bag and a tent in his car and sleeping under the stars half the time.

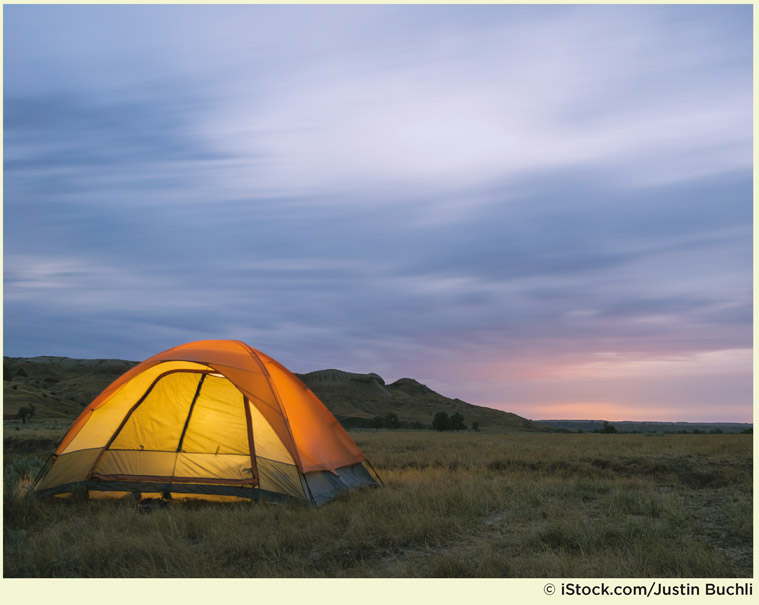

Camping is not the most comfortable thing in the world—and probably no one who does it would tell you they do it because it’s comfortable. It’s cold, or sometimes hot, and if you have to go to the bathroom in the middle of the night, you have to unzip a sleeping bag and get yourself up off the ground. There’s no running water, it’s harder to wash dishes, you usually cook on only one or two burners, and things are generally just less convenient.

But, as Fred illustrated, it can make the world your oyster. It can make unaffordable trips suddenly affordable, it can make the inflexible schedules dictated by hotel reservations flexible, and if you do it, I guarantee you’ll see way more sunsets and sunrises.

Camping, to me, isn’t a lifestyle. It’s a tactic. I’ve spent months on the road, living out of my car, something I never would have been able to do if I told myself I absolutely had to stay in an Embassy Suites every night of my vacation. They don’t build many affordable hotels on California and Oregon oceanfronts, or in thick stands of Montana and Washington old-growth trees, or in the Utah and Arizona deserts. But there are plenty of campsites in those places, and I’ve enjoyed some pretty fantastic views while brushing my teeth standing next to my car or my tent instead of in some sterile hotel room bathroom.

Camping doesn’t have to be your favorite thing in the world to turn a $3,000 road trip vacation into a $500 road trip vacation. It’s a means to see more of the world with the money you have, and if you do it, you’ll probably see way more of the world because you won’t have hotel walls blocking your view. It’s not always sunny, warm, and cushy, but if you do it enough times, it actually might turn out to be your favorite thing in the world.

Kit Noble

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: Skiing Tuckerman Ravine on Mount Washington’s southeastern face is a tradition that’s been going on since the 1930s, when the Civilian Conservation Corps cut a ski trail from Pinkham Notch to the base of the ravine and built a warming hut, making access easier and paving the way for ski races. It’s one of the most famous rites of passage for East Coast skiers, filling the parking on the sides of the road at the trailhead and the 3-mile trail itself. Some people show up to ski the famous bowl, and some just show up to watch.

It’s not full-on backcountry skiing—the season for most skiers is in late April and early May, after the snowpack has consolidated—but it’s not beginner skiing either. The easiest line of the 10 lines is 35–45 degrees, and the only way to get to the top is to bootpack all the way. Oh, and the hike to get to the base of the bowl takes most people about 3 hours. If you fall and get injured, there’s no ski patrol to come to your aid. That said, serious accidents are fairly rare, and if you’re a confident black-diamond skier, Tucks is a fun adventure and unique to East Coast skiing in that it’s a long, run-out ski path with no trees in the way.

Wear a helmet, practice your steep turns during ski season before you go, and be ready for some quad-burning hiking before your run down.

SEASON: Late Apr–early May (dependent on snowpack)

INFO: cathedralmountainguides.com

flickr.com/Stanislav Sedov

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: If you love long mountain bike rides with expansive desert vistas, the Whole Enchilada is for you. If you prefer your long mountain bike rides to have a 5½-to-1 downhill-to-uphill ratio, the Whole Enchilada is really for you: It’s 34 miles of riding, lots of technical descending, and a fair amount of fire road. You’ll start in the mountains at 10,500 feet and climb to 11,150 feet before descending almost 8,000 feet into the desert over the course of the day. Total uphill pedaling: 1,400 feet.

By most mountain biking standards, the Whole Enchilada is a huge day in the saddle. Expert mountain bikers love it, intermediate bikers will find it to be a good challenge, and everyone who’s ever pedaled a mountain bike in Moab will wonder about it until they’ve done it at least once.

The best way to experience the ride is to take a shuttle van to the top (you’re more than welcome to ride the 7,900 feet of ascent from town up to the start, but it’s rare) for $30 per person. Pack enough water, food, and sunscreen for a big day. Also, do yourself a favor by riding a couple Moab-area trails before taking this one on, so you can get used to the terrain first. Riding it on a hardtail is possible (technically everything is), but most riders will want a full-suspension bike. If you don’t own one, plenty of shops in Moab will let you demo one for the day.

SEASON: May–Oct (September and October have the best temperatures.)

INFO: wholeenchiladashuttles.com

COLORADO’S 14,060-FOOT MOUNT BIERSTADT is one of the most popular “14er” hikes in the state—it’s a 1½-hour drive from the urban center of Denver, it’s a short hike at 7 miles round-trip, and it’s the easiest trail to the top of all the 58 14,000-foot peaks in the state. Even on weekday mornings, if you hike it, you’ll be accompanied by 100 to 300 people—and weekends are even more popular.

Just across the street—or, more accurately, across Guanella Pass Road—there’s another mountain: Square Top Mountain. It’s a 6.5-mile hike to a 13,794-foot summit, has great views of the Colorado Rockies from the top, and is relatively ignored compared to its neighbor across the way. Why? Because people just want to climb a 14er in Colorado, and Square Top is 206 feet shy of that title.

Now, this doesn’t bother me a bit—I’ll take the solitude whenever I can get it, and I think everyone should take the opportunity to check “climbing a 14er” off their list when they can. But it illustrates something I’ve noticed about the outdoors: Right next to the really popular (and sometimes even crowded) thing, there’s a pretty good alternative.

This is especially true in national parks: Hundreds of people do the 3-mile round-trip hike to Delicate Arch in Arches National Park, and it feels crowded because you’re all headed to the same viewpoint at the end: the one right in front of Delicate Arch. But a few miles up the road, you can do a longer hike on the Devils Garden Loop, see several striking and varied arches, and see way fewer people at each one. Same thing with Angels Landing (crowded) and Observation Point (not nearly as crowded) in Zion National Park or Chasm Lake (popular) and Black Lake (almost no one there) in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Obviously, the popular places are popular for good reason—they’re beautiful, great experiences, and often attainable for most people. But as the saying goes, “Nothing draws a crowd like a crowd.” Lots of people go to those popular, big-name spots just because they’re well known and it’s easy to find information about them online or through word of mouth. If you do a little more research, you might find a lot more solitude.

One thing you can do when visiting a national park is ask a ranger or other employee at an information center, “What’s the most popular hike in the park?” When they answer, you can say, “Okay, so we should avoid that. Where do you go when you’re not working?” You’ll get an answer that will probably lead you to a place that’s just as great as “the most popular hike in the park” but with way fewer people.

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: As you wind up Zion Canyon in one of the Zion National Park shuttle buses, the walls get closer and closer together until you’re craning your neck and smooshing your face against the window of the bus trying to see the tops of the formations thousands of feet above the road along the canyon floor. By the time the bus reaches the back of the canyon, you might have noticed some passengers wearing strange-looking water shoes and carrying hiking sticks or trekking poles. They’re going to do a one-of-a-kind hike called “the Narrows.”

The Narrows are where the walls of Zion Canyon rise straight up from the banks of the Virgin River, with towering sandstone walls only a few dozen feet apart. The hike begins where the concrete riverwalk trail ends, and you step right into the river and walk upstream. It’s a unique hike with unique gear needs, and you should definitely consider trekking poles or a hiking stick, as well as water shoes. You don’t have to buy specific water shoes just for this hike—rent them at outfitters in nearby Springdale, or just wear a pair of nonwaterproof hiking shoes or trail-running shoes (waterproof shoes will fill up with water and weigh a ton). Consider neoprene socks to keep your feet warm. Take a drybag for clothes, food, and electronics that you don’t want to get wet.

The great thing about the Narrows is that you can have a great experience no matter how far you go. Most people suggest taking 6 to 8 hours to get to the best spots on the hike, but even a few minutes upriver and back will deliver some great views.

SEASON: Summer–fall

INFO: nps.gov/zion

© iStock.com/cpaulfell

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: Mount Si is one of the most popular hikes in the Northwest, thanks to the views from the top (you can see Mount Rainier on a clear day), its length (8 miles round-trip), and its proximity to Seattle (45 minutes from downtown with no traffic). But it also stymies plenty of hikers, thanks to its steepness—the trail gains 3,150 feet from trailhead to summit and is a walk in the park for no one.

But that makes it a proud day hike. More than 100,000 people start up the trail each year, grinding up the endless switchbacks through old-growth forest to the top of the trail. The views from the top of the hike peek into the Cascades, the Olympics all the way on the other side of Seattle, and to Mount Rainier to the south. The true summit of the Haystack, the rocky outcrop at the top of Mount Si, can be reached with a few hundred feet of scrambling. CAUTION: Be warned; it’s exposed and serious, and a fall could very likely be fatal.

Mount Si is used as a training hike for many who have their sights set on Mount Rainier and a great intro to the terrain of the peaks of the Pacific Northwest and the Cascades, the sea of craggy, glaciated peaks to the north. Even if you don’t ever climb anything else in the Northwest, Mount Si is a proud hike.

SEASON: Year-round, although winter hikes might require trail crampons

INFO: wta.org/go-hiking/hikes/mount-si

YOU’RE PLANNING YOUR DREAM ADVENTURE TRIP, and like a lot of things, it requires a lot of specialized gear, which can get expensive. What can you do? Here’s one idea: Don’t buy every single piece of gear.

For example, to climb Mount Hood with a guide, you need mountaineering boots ($300), crampons ($130), an ice axe ($80), a climbing helmet ($60), and a climbing harness ($50)—not to mention the clothing you may or may not already own. That’s $620 in specialized gear you’re buying without knowing if you’ll even like mountaineering enough to do another climb.

Here’s how you save some money: One guide service will rent you crampons, mountaineering boots, and an ice axe for $66 for the entire climb and will let you borrow a harness and helmet for free. Congratulations, you just saved yourself $554 on the cost of your climb (almost enough to pay for a friend to join you!).

In 2015, my girlfriend and I planned a bike tour in northern Norway. We could have shipped our own bikes there for $100 apiece each way, plus purchased racks and panniers for the bikes to carry all our gear ($420 per person), a total of $620 per person. But a bike shop in Tromso rents fully equipped touring bikes for $25/day. For our 10-day trip, that would cost us $250 each, saving $370 each. Also, we wouldn’t have to worry about our bikes getting damaged flying to and from Norway. It was a no-brainer for us—we rented the bikes, rode them for 10 days, and had a blast.

You may not want to rent everything—mountaineering boots, for example, can be a personal choice. If you have issues with shoes fitting correctly or find yourself getting blisters, you might want to buy your own mountaineering boots. You can always use them as hiking boots (they’re a little bit of overkill for that, but they work just fine and allow you to get more out them than just a onetime investment). Rental skis and boots are another personal choice—if you’re only skiing a few days every year, it makes sense to rent skis and boots. If you have bad luck with rental boots fitting you, you might want to buy your own boots and just rent skis. If you don’t like to travel with skis (it’s not that much fun hauling your ski bag around an airport), you can always use your own boots and rent skis when you get to the resort.

There’s no magic equation for renting vs. buying—a lot of it comes down to personal choice and what you want to keep in your garage or house after your trip is over. Buying all the gear for a onetime thing can be a costly way to collect souvenirs, and a kayak, for example, takes up a lot more room than a pair of crampons. Just do a little research and understand your options, then figure out what works best for your needs on that specific trip.

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: Imagine hiking to the summit of a mountain, overing almost a vertical mile of elevation gain, and then going back down again over the course of a long day of 23 miles of moving. Okay, now imagine doing it in reverse—down first and summit second. That’s what hiking from one rim of the Grand Canyon to another is like, except, of course, you’re walking all the way across one of America’s most famous national parks, and you have to get a ride back to your car when you’re done.

A rim-to-rim hike of the Grand Canyon (or vice versa) is so highly coveted it’s very difficult to get a backpacking permit for a 3- or 4-day leisurely experience. Instead, many opt to hike from one rim to another in one day, a challenge but doable by any fit weekend warrior who can move at a decent clip. The mileage for the hike is the same in both directions, but since the North Rim is 1,400 feet higher in elevation than the South Rim, hiking south to north is a bit more strenuous than north to south.

Either way is a fantastic trek through millions of years of geology visible in the distinct layers of canyon rock. Hikers should take plenty of food and water (you’ll be able to refill bottles at the bottom), a headlamp, and appropriate layers of clothing for temperature changes throughout the day and through different elevations. A 4-hour van shuttle takes hikers between the rims during high season, but plan for lodging at the rim where your hike ends—the shuttle leaves in the morning not in the evening. Alternately, plan for a friend to drive your car around to pick you up at the end of your trek.

SEASON: Late Sept–mid-Oct

INFO: nps.gov/grca, trans-canyonshuttle.com

© iStock.com/frontpoint

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: If you can wrap your head around rock climbing without thinking, “That’s crazy!” then surely climbing up a frozen waterfall with ice picks in your hands and spikes on your feet doesn’t strike you as that far-fetched.

A couple tips: The things in your hands are actually called ice tools, and the spikes on your feet are actually called crampons. Ice climbing is cold, but if you’ve ever gotten cold while ice-skating or skiing and decided you were still having fun despite the temperatures, you’ll probably be fine ice climbing. Also, you don’t need to be a superhero who can do 200 pull-ups in a row to be able to climb ice. Most people will tell you that you don’t even need to be able to do one pull-up (but it might help a little bit).

New Hampshire, with its cold winter temps and wetter mountain climate, has some of the best ice climbing in North America, from steep frozen waterfalls to long ice and snow gullies in the White Mountains. Like rock climbing, ice climbing requires special gear and training (including ropes), but a guide can teach you the basic skills in a day and take you up a classic climb the next day (depending on your comfort level on the ice and with the equipment). It’s cold and maybe a little difficult to explain to your coworkers on Monday morning, but it’s also one of the most exhilarating experiences you can have outdoors.

SEASON: Dec–Mar

INFO: cathedralmountainguides.com/new-hampshire-ice-climbing

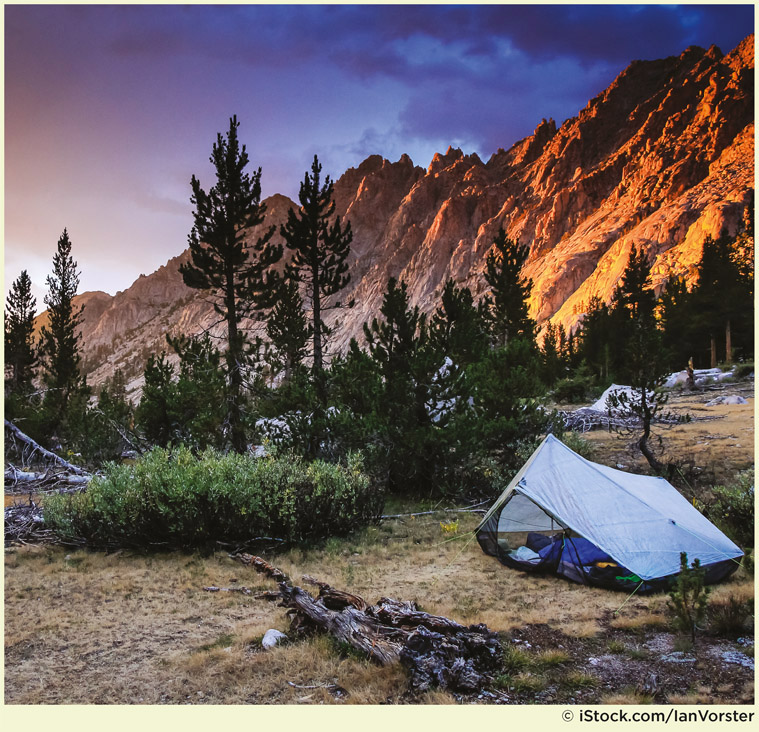

EVERY YEAR ON MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND and Labor Day weekend, I watch a mass migration from my hometown of Denver as thousands of cars clog the inter-states and highways to head out of town and go camping. If you didn’t know better, you might think these two weekends were the only possible times of the year to go camping in Colorado.

Here’s a secret: They’re not. You can camp on any weekend, and if you’re strategic about it, you can even camp on a weeknight. That’s right. Here’s one more secret: Almost no one goes camping on weeknights, so all those campgrounds and campsites near where you live and that fill every Friday and Saturday night during the summer are empty and quiet the other 5 nights a week.

Yes, it’s not a 3-day weekend. Yes, if you camp on a weeknight, you might have to sacrifice your eggs-and-bacon camp breakfast in order to make it into the office on time the next morning. But time in nature is time in nature, however you get it. If you normally like to eat three slices of pizza at a time and someone instead offered you (a) one slice of pizza or (b) no pizza at all, which would you choose? I’d choose option a every time.

So, how can you get a weeknight outside? Find a state park or county park near your town, pack the car the night before, and leave work an hour early just like you would if your kids had a baseball game or a dentist appointment. Get out of town, set up your tent, cook dinner, and enjoy escaping your routine for a night. Wake up early the next morning, eat a quick breakfast, and head home to shower before work—or better yet, sleep in a little bit and see if you can get away without showering before heading into the office. This usually works best on Casual Fridays.

Small doses of nature are good for you, and you might discover that it’s a lot less hectic to do a few nights of camping on summer weeknights instead of joining the hordes leaving town for those two long weekends. When I used to work in an office, I would set a goal of sleeping outside for 30 nights every year. With a couple weeks’ vacation, as many weekends as possible during the spring, summer, and fall, and a few week-nights during the summer, I always reached my goal.

Not every one of those weeknights camping was fantastic, but I’ll tell you what: They were way better than staying home and feeling the pressure to do laundry, answer e-mails, do small housework jobs, or run errands. And when you’re sitting by a camp-fire on a Thursday night with hardly a neighbor around at a campground that will be full the next night, you really feel like you’re getting away with something. Even if you’re only 12 or 13 miles from your house.

flickr.com/Dankarl

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: How would you like to have the chance to spend 11 hours on a school bus? Not interested? How about if the bus were driving into Denali National Park on the only road into the park, where cars aren’t allowed?

Short of skiing into the park by yourself, the Denali National Park shuttle bus is the easiest way to see the tundra, rivers, and huge mountains that make the park famous. The shuttle bus drives the dirt Denali Park Road from near the park entrance 85 miles into the park, stopping at viewpoints along the way and finally for lunch at Wonder Lake, where, if you’re lucky, you’ll get a view of the park’s 20,320-foot-high namesake peak. Then you’ll head back. The bus ride is not narrated, but if you’re lucky, you’ll see some of the park’s megafauna—moose, caribou, grizzly bears, and even wolves. All this for less than $50 per person.

Narrated bus tours of the park are available, including going even farther down the park road to the old gold mining town of Kantishna, for around $200 per person.

SEASON: June–mid-Sept

INFO: reservedenali.com

Chris Shane

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: The highest point in the state of Maine, the summit of Katahdin, is about 10 feet lower than the city of Denver, but its reputation is more than a mile high. It’s most famous as the northern terminus of the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail, a majestic end point for trekkers who started their journey 6 months prior in Georgia.

The name Katahdin doesn’t refer to a single summit but to a massif with seven subpeaks: Baxter Peak, the actual summit (5,270 feet); South Peak (5,260 feet); Pamola Peak (4,919 feet); Chimney Peak (4,900 feet); Hamlin Peak (4,756 feet); South Howe Peak (4,740 feet); and North Howe Peak (4,700 feet). The treeline is much lower at Katahdin’s high altitude (between 3,500 and 3,800 feet), meaning the upper 1,500 feet of the mountain is exposed glacially carved granite, and there are views in every direction.

The most famous ridge on Katahdin is the Knife Edge, a 1,500-foot section of 3-foot-wide ridge with a 1,000-plus-foot drop on either side. It’s worth watching your step up there. On rare occasions, hikers have slipped off during rainy or snowy weather, and on even rarer occasions, hikers have been blown off the ridge. However, most make it safely through the traverse to the summit. There are many routes to the summit, and the Knife Edge is only one of them. The most popular trail to the top is the 5.2-mile Hunt Trail, almost half of which is above treeline.

SEASON: Mid-May–mid-Oct

INFO: baxterstatepark.org

WHEN I WAS FIRST GETTING INTO THE OUTDOORS, a friend and I decided to climb Borah Peak in Idaho, the tallest mountain in the state. Halfway up the start of the scrambling to the summit, we came upon a couple also headed to the top. While chatting, we discovered that they were on a trip out west from Pennsylvania to climb a bunch of state highpoints—Borah Peak in Idaho, Wheeler Peak in New Mexico, and a few others. The man said something that’s always stuck with me: “Americans do all this traveling all over the world, and they’ve never seen this.”

It was a pretty good place for him to say something like that, looking over the mountains rising high above the plains of eastern Idaho, and I think he had a valid point: There’s plenty to keep us busy, and in awe, right in our own backyards, if we just look for it.

Now, I would never discourage anyone from traveling internationally, for the many rewards it offers (not the least of which is seeing another culture’s priorities). But sometimes those across-the-ocean trips are tough for varying reasons—too much time off work, too much money this year, not affordable for a family with kids. And in those cases, I don’t think we should shrug our shoulders and say, “Well, we can’t afford to go to India this year, so we might as well give up on having any fun.”

We have mountains in our own country—on both coasts, as you know. We have access to thousands of miles of ocean coastline, tons of lakes and rivers, and thousands of miles of trails. Yes, not all of our trails lead to the summit of something like Mount Fuji, and not every surf spot is as good as the North Shore of Waikiki. But if you just get out there, whether it’s a national park two or three states away or a county park 20 minutes away, I think you’ll find there are plenty of things that are more rewarding than another weekend of binge-watching Netflix shows (not that that’s not rewarding in its own way, but let’s be honest, you can binge-watch Netflix shows anytime).

I’m willing to bet that if you take a look at a map of where you live, you can find at least a handful of things you haven’t done—trails you haven’t hiked, places you haven’t camped, creeks or rivers you haven’t floated or fished, maybe even miles of paved bike paths you haven’t pedaled (and maybe at the end of those bike paths, bakeries you’ve never been to). You don’t have to leave the country to have an adventure. You probably don’t even have to leave your state. And, depending on where you live and your perspective, you may not even have to leave your county.

flickr.com/Zach Dischner

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: If you were to announce to a room full of veteran mountain bikers that you thought the Monarch Crest Trail was the best ride you’d ever done, you wouldn’t hear a lot of arguing. The 34-mile trail in Colorado’s high country has made it on dozens of Top 10 lists throughout the years, and rightly so: single-track winding in and out of wide-open, high-altitude mountain views, enough climbing to feel like you’ve earned the views, and 6,000 feet of descending.

The ride begins on Monarch Pass, elevation 11,312 feet, and climbs to just under 12,000 feet before starting its epic descent. It’s not “all downhill from there,” however. There are plenty of small climbs throughout the ride, and most riders who finish it say it feels like a lot more uphill riding than the approximately 2,000 feet it’s usually billed as having.

Show up in shape. If you haven’t been on a few 5- or 6-hour mountain bike rides with some substantial ascent and descent before signing up for a Monarch Pass ride, you’ll probably get a little beaten up by that sort of ride at high altitude. Know the route and arrange your own car shuttle to the beginning and end, or go on a group ride with a local bike shop, with demo bike provided in the cost.

SEASON: Mid-July–late Sept

INFO: absolutebikesadventures.com/guided-rides/monarch-crest-trail

© iStock.com/Sean Pavone

LENGTH: Full-Day

DESCRIPTION: Understand one thing if you decide to climb Mount Fuji: You’re not doing it for the solitude. It’s more of a cultural experience on a mountain. It’s far from a wilderness experience, with vendors selling food and drinks, sleeping huts and hostels on the way up, and more than 300,000 people attempting to make it to the summit every year—mostly during the official climbing season from early July to early September.

But, unlike shopping the day after Thanksgiving, braving the crowds on Mount Fuji is actually worth it, especially if you get to the top in time to see sunrise. And don’t be lulled into complacency by the number of hikers. It’s still a mountain, with mountain weather, high altitude, and changing conditions. It’s 12,389 feet tall, and if you climb the most common route, the Yoshida route, you’ll ascend almost 5,000 feet by the time you get to the summit.

To get to the top by sunrise, you’ll climb by headlamp, somewhere in the endless stream of other climbers’ headlamps and flashlights. If you make it in time and have clear weather, you might see Mount Fuji’s shadow stretching 15 miles long down on the valley floor and the lights of nearby Tokyo.

SEASON: Early July–early Sept

INFO: fujisan-climb.jp/en

FACT: IF YOUR CAR BREAKS DOWN ON THE SIDE OF A HIGHWAY in the desert, miles from nowhere, you don’t have to have a AAA card to get your car towed to the nearest town to get fixed. But depending on your membership level and the distance to said nearest town, if you do have a AAA card, you could get your car towed for free, which is pretty nice.

My girlfriend and I travel a lot, sometimes together, sometimes separately, and our total AAA couples’ membership costs less than $80 a year. We use our cards separately for hotel discounts, Amtrak ticket discounts, and thankfully, we rarely have to use it for roadside assistance, towing, or jump-starts (but those are also benefits).

I don’t work for AAA—I just like to be prepared and not spend unnecessary money, so I recommend the AAA card to people who travel a lot. If you spend 10 nights a year in a hotel and save $10 on each hotel room, the card has paid for itself.

Most people have heard of AAA, but not everyone’s heard of the AAC—the American Alpine Club. Even if you’re not a mountain climber, you should have an AAC membership (also less than $80/year). Why? For one thing, you can take advantage of the AAC’s rescue insurance if you ever hurt yourself in the mountains and need a rescue—that includes spraining your ankle 3 miles from the trailhead on a day hike.

The AAC card will also get you deals on outdoor gear, discounts on lodging in mountain huts all over the world, and discounts on accommodations at climbers’ hostels and campgrounds in places like Grand Teton National Park. And perhaps my favorite membership benefit: the American Alpine Club library, which will lend you any of its hundreds of international hiking and climbing guidebooks by mail. So if you’re going to Italy to hike the Alta Via 1 in the Dolomites, you can get a guidebook and discounts on every mountain hut you stay in over the course of your trip—and if you happen to need a helicopter rescue, you’re covered for that, too.

Both cards are very low-cost insurance policies in their own ways and I think a worthy—but minimal—investment for anyone who wants to have adventures big or small and live to tell about them.