INTRODUCTION

The poet Dylan Thomas wrote that one should not go gently into that good night, that old age should burn and rage at close of day. As a younger man reading that poem, I saw futility in those words. I saw aging only as a failing: a failing of the body, of the mind, and even of the spirit. I saw my grandfather suffer aches and pains. Once agile and proudly self-sufficient, by his sixties he struggled to swing a hammer and was unable to read the label on a box of Triscuit crackers without his glasses. I listened as my grandmother forgot words, and I cried when eventually she forgot what year it was.

At work, I watched as people neared retirement age, the spark gone from their eyes, the hope from their smiles, counting the days until they could walk away from it all, yet with only the vaguest plans about what they would do once they had so much free time, all day, every day.

But as I’ve grown older myself, and have spent more time with people who are in the last quarter of their lives, I’ve seen a different side of aging. My parents are now in their mideighties and are as engaged with life as they have ever been, immersed in social interactions, spiritual pursuits, hiking, and nature, and even starting new professional projects. They look old, but they feel like the same people they were fifty years ago, and this amazes them. Where certain faculties have slowed, they find that extraordinary compensatory mechanisms have kicked in—positive changes in mood and outlook, punctuated by the exceptional benefits of experience. Yes, older minds might process information more slowly than younger ones, but they can intuitively synthesize a lifetime of information and make smarter decisions based on decades of learning from their mistakes. Among the many advantages of being old, they are less fearful of calamities because they’ve been dealt a few in the past and managed to work through them. Resilience—both their own and each other’s—is something they know they can count on. At the same time, they are comfortable with the idea that they may die soon. That’s not the same as saying they want to die, but they no longer fear it. They’ve lived full lives and treat each new day as an opportunity for new experiences.

Brain researchers speculate that old age brings chemical changes in the brain that make it easier to accept death—to feel at ease with it rather than be frightened by it. As a neuroscientist, I’ve wondered why some people seem to age better than others. Is it genetics, personality, socioeconomic status, or just plain dumb luck? What is going on in the brain that drives these changes? What can we do to stem the cognitive and physical slowdown that accompanies aging? Many people thrive well into their eighties and nineties, while others seem to retreat from life, prisoners of their own infirmities, socially isolated and unhappy. How much control do we have over our outcomes, and how much is predetermined?

Marrying recent research in developmental neuroscience with the psychology of individual differences, Successful Aging sets out a new approach to how we think about our final decades. Drawing from diverse disciplines, this book demonstrates that aging is not simply a period of decay, but a unique developmental stage that—like infancy or adolescence—brings with it its own demands and its own advantages.

The book will show that how well we age depends on two parallel streams:

-

the confluence of a number of factors reaching back into our childhoods; and

-

our responses to stimuli in our environments, and shifts in our individual habits.

This provocative argument can revolutionize the way we plan for old age as individuals, family members, and citizens in industrial societies where the average life expectancy continues to rise. It offers choices we can make that will keep us mentally agile well into our eighties, nineties, and perhaps beyond. We need not stumble, stooped and passive, into that good night; we can live it up.

Two of the teachers I had in college are now in their eighties and another is in his nineties. All are still active and whip-smart. One of them, Lewis R. Goldberg, now eighty-seven, is considered the father of modern-day scientific conceptions of personality—the unique compendium of traits and features that set us apart from one another and that can profoundly influence the course of our lives. He has found that personalities can change: You can improve yourself at any stage of life, becoming more conscientious, agreeable, humble—any number of things. This is surprising, and it upends decades of casual speculation. We tend to think of personality traits as being durable, persisting forever. (Think of the curmudgeon Larry David in TV’s Curb Your Enthusiasm.) But personality traits are also malleable. And the degree to which habitual traits drive our behavior is influenced by the situations we find ourselves in and by our own striving to improve ourselves, to become better people.

The darker side of this, unfortunately, is that some encounters and environments can cause our personalities to change for the worse. Learning how to avoid certain environments, habits, and stimuli that influence our personalities in negative ways is a crucial part of aging well. This potential malleability of personality as we age is essential to understand. Dark shifts in personality are, regrettably, all too common in our world. We all know of people who have grown bitter, isolated, or depressed as they got older.

Much of this is culturally driven. In the 1960s, when I grew up, many young people couldn’t wait to push old people out of the way. For all the tolerance, peace, and love that our Woodstock generation espoused, we were quick to try to sideline our parents’ generation. We chanted, “Don’t trust anyone over thirty,” and we might as well have chanted, “Don’t even pay attention to anyone over seventy.” Roger Daltrey of the Who summed up a pervasive sense of derision toward the elderly when he sang, “I hope I die before I get old.” My friends who were born in the 1930s and 1940s have shared with me stories of indignities, prejudices, and disrespect shown toward them by people of my generation.

Aging, as it has been depicted in the media and our collective consciousness for centuries, implies both physical and emotional pain and, in many cases, social isolation. As the body became more frail, intellectual faculties weakened, and diminished vision and hearing prevented the elderly from engaging with their communities as they once did. Retirement spelled the end of life’s purpose and, sadly, seemed to accelerate the end of one’s life.

My grandfather, a first-generation college student who worked his way through medical school to become one of the first radiologists in California, was pushed out of the very department he founded at his hospital, just because he turned sixty-five. From what we know today about diagnostic radiology, he was probably better at his job at sixty-five than when he was younger, because so much of it depends on pattern-matching circuits in the brain that improve with experience. The sense of marginalization and uselessness my grandfather experienced in the workplace was opposite what he had with us at home in the family—we loved and venerated him, and we were devastated when he died at sixty-seven. In a letter he wrote to the family before the surgery that ultimately cost him his life, he expressed deep sadness about the “loss of respect” for him at the hospital. I always suspected that this loss of respect had an impact on his stamina, resilience, and mood to such a degree that a minor surgical complication cost him his life.

I want to draw out explicitly what happens in the brain when we feel rejected or underappreciated. Our bodies react to insults, both psychological and physical, by releasing cortisol, the stress hormone. Cortisol is very useful if you need to invoke the fight-or-flight response—say, when you’re confronted by an attacking tiger—but it is not so useful when you’re dealing with longer-term psychological challenges such as loss of respect. The cortisol-induced stress reaction reduces immune-system function, libido, and digestion. This is why, when you’re stressed, you might have an upset stomach. It makes sense for the fight-or-flight response to do this: It needs to direct all your resources to the temporary state of physically dealing with an imminent threat. But the psychological stresses that can come from interpersonal conflicts, left unresolved, can leave us in a physiologically stressed state for months or years. In contrast, when we’re actively engaged and excited about life, our levels of mood-enhancing hormones such as serotonin and dopamine increase, and the production of NK (natural killer) and T cells (lymphocytes) also increases, strengthening our immune systems and cellular repair mechanisms. My grandmother, my family, and I might have enjoyed my grandfather’s company a lot longer if social stressors hadn’t come into play.

Fast-forward twenty-five years. My own father, a businessman, was strongly encouraged to retire when he was sixty-two, to make way for someone younger. Like his father before him, he felt pushed out and began to question his self-worth. His social world shrank, he began to suffer physical ailments, and he became depressed. But by then, in 1995, the tide was already turning. Society and employers were awakening to the Eastern idea that the elderly may be not only of some value, but of superior value. My father put out feelers and was offered a job teaching a course at the USC Marshall School of Business. Soon he was teaching a full load of four courses per semester. That was twenty-five years ago. My father just signed a four-year renewal to teach until he’s eighty-nine. The students love him because he is able to pass on his real-world experience to them in a way that younger professors can’t. And by the way, that depression and those physical ailments were dramatically reduced once he found meaningful work.

Of course, finding ways to stay active and engaged is not always easy in old age, and it doesn’t completely compensate for biological decline. But new medical advances and positive lifestyle changes can help us to find enhanced fulfillment in life where previous generations may not have been able to do so.

When I was in college, one of my favorite professors was John R. Pierce, a former director of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the inventor of satellite telecommunication, a prolific sci-fi writer, and the person who named the transistor when a team under his supervision invented it. I met him when he was eighty, in the second iteration of his “retirement,” giving classes on sound and vibration. He invited me to dinner at his house once; we became friends and went out to dinner regularly. Around the time John turned eighty-seven, he grew depressed. One of the pastimes he enjoyed most was reading, but now his eyesight was failing. I bought him some large-type books and that perked him up for a few weeks, but much of what he wanted to read—technical books, science fiction—was not available in large type. I’d go over and read to him when I could, and I arranged for some Stanford students to do the same. But he still kept slipping. Then he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. His shaking bothered him. His memory was failing. He no longer found pleasure in things that he used to enjoy. And he was growing increasingly disoriented.

I suggested that he ask his doctor about taking Prozac, which was new at the time, and just being prescribed for the kinds of age-related problems he was facing. (Prozac helps to boost levels of serotonin in the brain—one of those mood-enhancing hormones I mentioned previously.) It was transformative. Although it didn’t help the Parkinson’s specifically, his attitude changed. He felt younger. He started holding dinner parties again, and lecturing to students, something he had given up doing just a year earlier. A simple chemical change in his brain gave him a second wind. John lived to ninety-two, and much of those last five years were filled with joy and satisfaction for him. And for me, too—it felt like getting a second chance with my grandfather who had died too soon.

I saw John two weeks before he passed at age ninety-two, and he was excitedly planning some new experiments he wanted to do. That’s the way to go out.

At the time I knew John, I was young and not thinking about my own inevitable aging. But in the decades since then, in experiencing my own gradual mood shifts and in talking to a great many research colleagues and doctors, I’ve come to see a future in which we can plan ahead to fend off some of the adverse effects of aging; a future in which we can harness what we know about neuroplasticity to write our own next chapters the way we want them to come out; a future in which healthy lifestyle choices and a broader use of antidepressants and other medications can temper or reverse the effects of depression and other changes in mood that we have for too long assumed were an irreversible part of the aging process. In addition, new innovations in medical science and treatment protocols are sure to become available.

For example, recent discoveries about changes in sleep chemistry and neuronal waveforms suggest a different approach to this most basic of human activities. Sleep deprivation at any age is bad for you. It has been tied to diabetes in pregnancy, postpartum depression in new fathers, and bipolar disorder at all ages. You may have read that “old people” don’t need as much sleep as young people and can get by on four or five hours a night. This myth has recently been exposed by Matthew Walker at UC Berkeley. It’s not that we need less sleep as we get older—it’s that changes in the aging brain make it difficult for older adults to get the sleep they need. And the consequences are serious. Sleep deprivation in the aged is directly responsible for cognitive decline, not to mention increased risk of cancer and heart disease. Grandma didn’t forget where she put her glasses because she’s senile—it’s because she’s sleep-deprived. Walker has found evidence that sleep deprivation increases the risk of Alzheimer’s.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is now the third leading cause of death in the United States. This doesn’t mean we should jump to the conclusion that there is an epidemic in the making, or that environmental toxins are causing it. They might be, but AD is primarily an old person’s disease; medical advances have made it so that we are living longer, and that means we are living long enough to get Alzheimer’s. Now, for reasons we don’t yet understand, AD is selective with regard to sex. Sixty-five percent of patients are women, and a woman’s chances of getting AD now exceed her chances of getting breast cancer.

Approximately two-thirds of the overall risk that you’ll get Alzheimer’s comes from your genes, with the remaining one-third associated with environmental factors such as whether or not you have a history of depression or head injuries. In this way, events of childhood can have an effect many, many decades later. Recent science demonstrates that environmental stimuli, behavior, and luck all play a role, as I will show throughout the book. On the biological side, a brain with Alzheimer’s is easily recognized by the shrinkage of the hippocampus—the seat of memory—and of the outer layers of the cerebral cortex (the part of the brain associated with complex thought and movements). You may have heard of amyloids, aggregates of proteins that have been found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. One particular protein, beta-amyloid, begins destroying synapses (connections between the brain’s neurons) before it clumps into plaques that cause the death of neurons themselves.

Dale Bredesen, a neurologist who studied under my colleague Stan Prusiner at UCSF, has studied these interacting factors for thirty years. His Bredesen Protocol is the topic of a New York Times bestseller. Fending off Alzheimer’s, he says, involves five key components: a diet rich in vegetables and good fats, oxygenating the blood through moderate exercise, brain training exercises, good sleep hygiene, and a regimen of supplements individually tailored to each person’s own needs, based on blood and genetic testing. The Bredesen Protocol is still in its early stages of validation—the primary proof of concept was based on only ten patients. The patients have to be in very early stages of Alzheimer’s. And since the protocol is new, they haven’t had anyone on it for more than five years. The protocol may or may not help, but at least the first four parts won’t cause any harm—we don’t know enough about the supplements—and to many it makes sense to start following these healthy lifestyle practices on the chance that they will end up being scientifically validated.

Prusiner won the Nobel Prize for discovering prions, proteins that can accumulate and cause neurogenerative diseases like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a fatal condition that is characterized by memory loss and behavioral changes. Sound familiar? These are the markers of Alzheimer’s, of course, and Prusiner now believes that prions, because they can assemble into amyloid fibrils, are responsible for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. At the cutting edge of this research is the idea of neuroinflammation as a precursor to Alzheimer’s, appearing long before clinical signs and symptoms. This is because the visible symptoms appear only during the actual destruction of brain regions—the cognitive effects we notice, such as memory loss and mood change, reflect relatively late stages of the underlying disease process. Depressive-like symptoms, such as loss of interest and energy, often appear long before other, more serious manifestations.

Several teams of scientists have found that a chronic inflammatory process precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s, and this strongly suggests a potential health-care strategy involving anti-inflammatory drugs, one that we might see in widespread use in the next few years. Current research is focused on whether anti-inflammatories (such as ibuprofen) can ease symptoms once they’ve arrived, or whether the drugs must be given before the onset of symptoms and thus act as a preventative (which is appearing to be the case). Another cutting-edge treatment being investigated involves immunization with antibodies that can prevent the formation of amyloid fibrils in the first place.

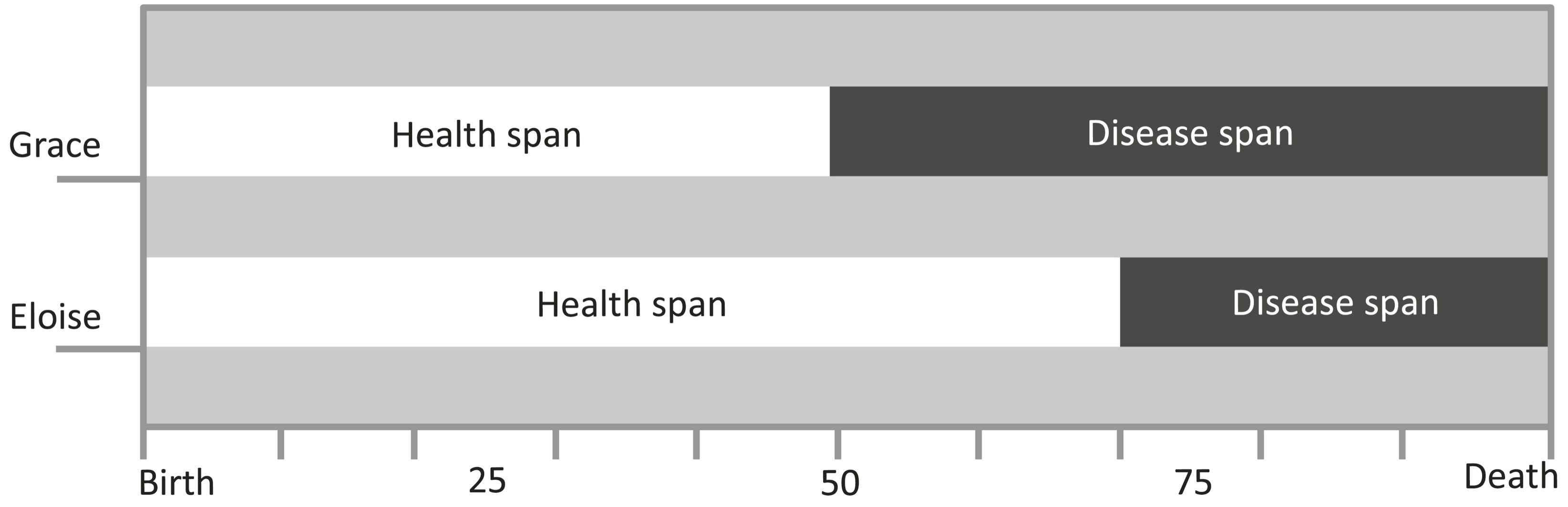

We talk about life span as the length of time that one is alive. Except for cases of death by accident, most of us will die of some kind of disease, or our parts will just wear out. You can think of the time line of your life span as being divided into two parts: the period of time that you’re generally healthy (the health span) and the period of time that you’re sick (the disease span). Obviously, it is important to minimize the disease span.

Consider two friends who die at one hundred, both with identical life spans but very different disease spans. Grace begins a gradual health decline at fifty and by eighty requires twenty-four-hour care. Eloise begins to decline at seventy but the real health problems don’t kick in until ninety-five. All of us would prefer to have that extra twenty years of smooth sailing, followed by an extra fifteen years of happy life before disease limits our activities. I wrote this book on the premise that it is never too late to tilt the balance in our favor, to increase our health span by making important changes to how we approach aging.

The environmental factors I’ve described here can have either a positive or negative impact on the way we experience old age—our engagement with the world, our habits, our will to live, and medicine. A second strand of the narrative for Successful Aging is the developmental side, a story that begins, ironically, in childhood.

I mentioned earlier that social stress can lead to a compromised immune system. That happens at any age. Michael Meaney at McGill University showed that the kind of care a mother gives to her offspring alters the chemistry of the DNA in certain genes involved in physiological stress responses. Rat pups who are licked more in the first six days of life grow into adult rats who are far more secure and less likely to be afflicted with stress. In particular, those baby rats that received a great deal of licking and grooming produced fewer stress hormones when dealing with a challenging or stressful situation than the rats who received less care, and here’s the kicker: The effects held well into adulthood.

Meaney has gone on to show comparable effects in humans, and the opposite set of outcomes for children who are neglected or abused as infants. In the stress story, early experience interacts with genetics and brain structure. “Women’s health is critical,” Meaney says. “The single most important factor determining the quality of mother-offspring interactions is the mental and physical health of the mother. This is equally true for rats, monkeys and humans.” Parents living in poverty, suffering from mental illness, or facing great stress are much more likely to be fatigued, irritable, and anxious. “These states clearly compromise the interactions between parents and their children,” he says. And, subsequently, they compromise their children’s brain chemistry and resilience in the face of setbacks—even future ones.

Meaney emphasizes that “human brain development occurs within a socioeconomic context, and childhood socioeconomic status (SES) influences neural development—particularly of the systems that subserve language and executive function” (deciding what to do next and then doing it). Research has shown the importance of prenatal factors, parent-child interactions, and cognitive stimulation in the home environment in promoting healthy, lifelong neural development. These findings should direct us toward improving the programs and policies that are designed to alleviate SES-related disparities in mental health and academic achievement.

Nurture (or lack thereof) early in life affects the development of a number of brain systems selectively, such as glucocorticoid (GLUE-co CORT-ick-oid) receptors in the hippocampus, which are a primary component of the stress response, part of the feedback mechanism in the immune system that reduces inflammation. Meaney also showed that parenting affects the function of the pituitary and adrenal glands, which regulate growth, sexual function, and the production of cortisol and adrenaline. Early traumas can last a lifetime. They can be overcome with the right behavioral and pharmacological interventions, but it takes some work. More cuddles and hugs go a long way, particularly in the vulnerable first year of life. As parents (and grandparents and teachers), our choices about how we raise our children in their first years will have a far greater impact on what their last years look like than we might previously have recognized.

A third strand of Successful Aging, along with environmental influences and neural development, is that I’ve come to see old age as a unique period of growth, a life stage with its own distinct character, rather than a period of decline or a gradual turning down of the dials and knobs one by one.

When many of us think of aging, what first comes to mind might be a panoply of age-related problems that we’re all familiar with: loss of vision, loss of hearing, aches and pains. What exactly happens when the brain and body age—what physiological changes affect our experience of ourselves and others? I’ll delve into these questions in this book, including brain cell atrophy, DNA sequence damage, compromised cellular repair functions, and neurochemical and hormonal changes.

I’ll also explore some effects that are just as common but less talked about. For example, most of us experience metabolic changes that mean you can’t just continue eating the same things you’ve always eaten and maintain your weight or your figure. We may become lactose intolerant. (Evolutionary forces were mainly concerned with digesting mother’s milk when we’re young, not eating ice cream when we’re fifty.) Our digestive system experiences changes that, along with causing lactose intolerance, may make us gassier as we age. Our skin becomes drier. Our eyes become drier. Caffeine may affect us differently or stop providing its beneficial effects entirely. Processing refined sugar becomes more difficult as our pancreas ages. Successful Aging will tell you what to expect, or perhaps explain some of the things you’re already experiencing. But this is not a book about problems. My goal is to provide some solutions, guidelines, and helpful tips from the cutting edge of scientific medicine about how to live fully and happily, in a way that pushes these infirmities and indignities to the background and allows us to fully experience the meaningful things in the third act of our lives.

Now that the Woodstock generation is entering our sixties and seventies, we have a chance to change the status quo about the role older people play in daily life. Of course, this satisfies our own self-interest, but, more important, it can help to rekindle our generation’s ideal of improving society, ideals like respecting the planet and all the living beings who call it home, helping those less fortunate than ourselves, promoting tolerance and inclusiveness, and allowing people who are different from us to embrace, not be embarrassed by, those differences.

The cost of sidelining the elderly is enormous in lost economic and artistic productivity, severed family connections, and diminished opportunities. We can begin to model better behavior by embracing those who are a generation ahead of us—our parents’ generation. And we can adopt practices that will keep us, as older beings, relevant and engaged with others well into our eighties and nineties . . . and perhaps beyond. I argue here for a very different vision of old age, one that sees our final decades as a period of blossoming, a resurgence of life that does not chase after our younger years, but instead embraces the gifts that time can bring.

What would it mean for all of us to think of the elderly as resource rather than burden and of aging as culmination rather than denouement? It would mean harnessing a human resource that is being wasted or, at best, underutilized. It would promote stronger family bonds and stronger bonds of friendship among us all. It would mean that important decisions at all scales, from personal matters to international agreements, would be informed by experience and reason, along with the perspective that old age brings. And it might even mean a more compassionate world. Among the chemical changes we see in the aging brain are a tendency toward understanding, forgiveness, tolerance, and acceptance. While older adults may become more set in their ways, and there is a tendency toward conservatism, they can at the same time become more accepting of individual differences and appreciative of the struggles that others have had to face. Older adults can bring a much-needed compassion to a world being rent by impatience, intolerance, and lack of empathy.

We have a silo problem in my field of cognitive neuroscience. There’s a tendency for researchers to talk to people in their own area, and not to talk across areas. In the last thirty years we’ve seen big, transformative advances in the understanding of many core ideas about personality, emotions, and brain development. But few people in one area talk to people in another, and so we’re left with a situation where neither medical professionals nor the public are able to leverage these advances for our individual and common good.

I was extraordinarily fortunate when I started out, to have mentors who were working in diverse areas, and all of them are still active—personality psychologists (like Lew Goldberg and Sarah Hampson, now eighty-seven and sixty-eight, respectively), cognitive psychologists (Michael Posner and Roger Shepard, now eighty-three and ninety, respectively), and developmental neuroscientists (Ursula Bellugi, now eighty-eight, and Susan Carey, now seventy-seven). This led me to bridge two areas that have maintained separate intellectual traditions—developmental neuroscience and individual differences (personality) psychology. The more I study the intersection of these two, the more intrigued I am at how they can help us to understand the aging brain and the choices all of us can make to maximize our chances of living long, happy, and productive lives. The intersection of these two scientific fields, and how they apply to aging, is the core theme that runs throughout Successful Aging, and something that no one else has written about for a popular audience.

The developmental neuroscience view I will present here is that it is the interactions among genes, culture, and opportunity that are the biggest determinants of

-

the trajectory our lives take;

-

how our brains will change; and

-

whether or not we’ll be healthy, engaged, and happy throughout our life span.

No matter what age we are, our brains are always changing in response to pressures from genes, culture, and opportunity. The choices we make dictate much of the lives we lead. But we are also affected by random things that happen to us, and the choices that others make. Opportunity, or lack thereof, is often a matter of luck, governed by large historical forces, such as wealth, plagues, access to clean water, education, and good laws. In ways both large and small your brain has been changed by your life’s experiences, whatever they are—by disappointment, love, interactions with key people, successes, illnesses, accidental injuries, pain, environmental toxins. In short, your brain is continually being changed by life itself.

I add to this perspective the rich body of work on individual differences. The story of traits—the ways in which we understand our individual differences—is one of the most fascinating stories in modern science. It traces its roots back to Aristotle, who explained differences in personalities among individuals as differences in their “matter.” The eighteenth-century scientist Franz Joseph Gall and the nineteenth-century scientist Sir Francis Galton launched the modern study of individual differences, with Gall even anticipating the modern neuroscientific idea that specific mental functions can be localized to different parts of the brain. (Gall invented phrenology, the study of bumps on the head; this has now been shown to be ridiculous, but his primary hypothesis of localization of brain function still stands today.) Gordon Allport, Hans Eysenck, Amos Tversky, and Lew Goldberg, among many talented others, established individual differences as a science and a rigorous field.

Individual differences psychology seeks to both characterize and quantify the thousands of ways that we humans differ from one another. It uses relatively sophisticated mathematical-statistical tools, such as principal components analysis, and seeks to understand not just the ways we differ from one another, but also the roots of these differences. The goal of this work has always been to predict others’ future behaviors—if I know that you’re conscientious, for example, will I have a better chance of knowing how you’ll react to a certain situation than if I didn’t know that about you?

So what can we do to maintain strength of body, mind, and spirit while coming to terms with the limitations that aging can bring? What can we learn from those who age joyously, remaining vital and engaged well into their eighties, nineties, and even beyond? How do we adapt our culture to service the needs of aging generations while also taking greater advantage of their wisdom, experience, and motivation to contribute to society?

Throughout this book, I’ll be reinforcing the lifestyle concept that we can change our personalities and our responses to the environment, while continually adapting to the random and unpredictable things life throws at us. This concept has five parts: Curiosity, Openness, Associations, Conscientiousness, and Healthy practices, what I call the COACH principle. This is not another book telling you to do sudoku. Successful Aging will explain what is going on in our brains as we age, and what we can do about it, based on a rigorous analysis of neuroscientific evidence.

Successful Aging has three aims: first, to harness our knowledge so that we can anticipate changes—both positive and negative—and put systems in place that will ease our transitions and minimize the possibility of unwanted outcomes. These can be as simple as establishing a good relationship with your doctor, taking supplements to improve myelination of the nervous system, and hiding a key in a lockbox in case you forget yours in the house (as I once did in subzero temperatures—before I had a lockbox). There are definite things we can do to dampen the ill effects of memory loss, perceptual loss, and the shrinking social circles that often accompany aging. We can fight to reverse the tendency to narrow our interests, to become set in our ways, and to fear even moderate risk taking. We can learn to exploit the wisdom and skills that we have attained, becoming much-sought-after friends, rather than forgotten old people.

Second, this book aims to stimulate all of us to think about what ingredients presage a feeling of life well-lived when we look back from the end of life. What decisions can we make, both ahead of time and in the present moment, that will maximize our life satisfaction and infuse our lives with meaning? In previous books, I’ve been vocal about the overuse of social media, including Facebook. Don’t get me wrong—I use them, and I think that they are a fantastic way of staying in touch with our friends and family who are scattered across great distances. But when you’re at the end of your life, lying on your deathbed, the research literature strongly predicts you won’t be saying, “I wish I had spent more time on Facebook.” Instead, you’ll probably be saying, “I wish I had spent more time with loved ones,” or, “I wish I had done more to make a difference in the world.”

Ultimately, this book aims to help us think completely differently about aging, as individuals, as community members, as a society; it aspires to advance the evolution of a culture that embraces the gifts of the elderly, weaving cross-generational interactions into the fabric of everyday experience. By looking at the science of the brain—specifically the insights from developmental neuroscience and individual differences psychology—this book seeks to induce a transformative understanding of the aging process, the final chapter of our human story.

When older people look back on their lives and are asked to pinpoint the age at which they were happiest, what do you suppose they say? Maybe age eight, when they had few cares? Maybe their teenage years because of all the activity and the discovery of sex? Maybe their college years, or the first years of starting a family? Wrong. The age that comes up most often as the happiest time of one’s life is eighty-two! The goal of this book is to help raise that number by ten or twenty years. Science says it can be done. And I’m with science.