1

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES AND PERSONALITY

The search for the magic number

I visited a day care center for preschoolers recently and was struck by how early the differences in children’s traits and individual dispositions show up. Some children are more outgoing, while others are shy; some like to explore the environment and take risks, while others are more fearful; some get along well with others and some are bullies—even by age four. Young parents who have more than one child see immediate differences in the dispositions of siblings, as well as differences between their offspring and themselves.

At the other end of life, there are clear differences in how people age—some people simply seem to fare better than others. Even setting aside differences in physical health, and the various diseases that might overcome us late in life, some older adults live more dynamic, engaged, active, and fulfilling lives than others. Can you look at a five-year-old and tell whether they will be a successful eighty-five-year-old? Yes, you can.

The discovery that aging and health are related to personality was the result of a lot of work. First, scientists had to figure out how to measure and define personality. What is it? How do you observe it accurately and quantitatively? Here, they may have taken inspiration from Galileo, who said, “The job of the scientist is to measure what is measurable and to render measurable that which is not.” And so they did.

Among the most solid findings is that a child’s personality affects adult health outcomes later in life. Take, for example, a child who was always getting into trouble in elementary school and continued to do so as a preteen. As a teenager, they might have smoked cigarettes, drunk alcohol, and used marijuana. In personality terms, we might say that this teenager was sensation- and adventure-seeking, high on the quality of extraversion, low on conscientiousness and emotional stability. The kid would have been at increased risk for hard drug use, or being killed in a motor vehicle accident while driving drunk. If they survived these increased risks in young adulthood but didn’t change their habits, they’d enter middle age with a highly inflated risk of lung cancer from smoking or liver damage from drinking. Even more subtle behaviors can influence outcomes many decades later: Early and compulsive exposure to the sun and sun tanning; poor dental hygiene; poor exercise habits; and obesity all take their toll.

One of the pioneers in the relationship between personality and aging is Sarah Hampson, a research scientist at the Oregon Research Institute. As Hampson notes, “Lack of self-control may result in behaviors that increase the probability of exposure to dangerous or traumatic situations and adversely affect health through long-lasting biological consequences of stress.” She has found that childhood is a critical period for laying down patterns of behavior with biological effects that endure into adulthood. If you want to live a long and healthy life, it helps to have had the right upbringing. Childhood personality traits, assessed in elementary school, predict a person’s lipid levels, blood glucose, and waist size forty years later. These three markers, in turn, predict risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The same childhood traits even predict life span.

Although these correlations between early childhood and late adulthood personality are robust, they tell only a part of the story. People age differently, and part of that story has to do with the interaction of genetics, environment, and opportunity (or luck). Scientists developed a mathematical way of tracking personality, comparing traits as they differ across individuals or change within a person over time. With it, we can talk about age-related, culture-related, and medically induced changes in personality, such as occur with Alzheimer’s disease. Often one of the first indications of a problem with your brain is a change in personality.

And in the past few years, developmental science has shown that people, even older adults, can meaningfully change—we do not have to live out a life that was paved for us by genetics, environment, and opportunity. The great psychologist William James wrote that personality was “set in plaster” by early adulthood, but fortunately he was wrong.

The idea that people retain the capacity to change throughout their life span didn’t take hold until the midseventies, when an idea first put forward by psychologist Nancy Bayley was popularized by the German developmental psychologist Paul Baltes:

Most developmental researchers do accept the notion that developmental change is not restricted to any specific stage of the life-span and that, depending upon the function and the environmental context, behavior change can be pervasive and rapid at all ages. In fact . . . the rate of change is greatest in infancy and old age.

Not everyone takes advantage of this capacity, but it is there, like the ability to adjust your diet or your wardrobe. The events of your childhood can be overcome and transformed based on experiences you have later in life. Bayley and Baltes’ big idea was that no single period of life holds supremacy over another.

Of course, the idea that people can change is the entire basis of modern psychotherapy. People seek psychiatrists and psychologists because they want to change, and modern psychiatry and psychology are largely effective in treating or curing a great number of mental disorders and stressors, especially phobias, anxiety, stress disorders, relationship problems, and mild to moderate depression. Some of these volitional changes revolve around improved lifestyle choices, while others entail changing our personalities, sometimes only slightly, to give us the best chance of aging well. To implement the changes that will be most effective, each of us might think about the fundamental components of how we are now, how we used to be, and how we’d like to be.

The collection of dispositions and traits that we have in any given period comprise our personalities. All cultures tend to describe people using trait-based labels, such as generous, interesting, and reliable (on the positive side) or stingy, boring, and erratic (on the negative side), along with more or less neutral or context-dependent terms such as boyish and breezy. This “trait” approach, however, can obscure two important facts: (1) we often display different traits as situations change, and (2) we can change our traits.

Few people are generous, interesting, or reliable all the time—opportunity and the fluidly evolving situations in which we find ourselves can exert a strong pull on what may be genetic predispositions toward certain behaviors and certain habitual ways of presenting ourselves to the world. Traits are probabilistic descriptions of behavior. Someone who is described as high on one trait (having a lot of it) will display that trait more often and more intensely than someone low on that trait. Someone who is agreeable has a greater probability of displaying agreeableness than someone who is disagreeable, but disagreeable people are still agreeable some of the time, just as introverts are extraverted some of the time.

Culture plays a role as well, both macro- and microculture. What is considered shy, reserved behavior in the United States (macrolevel culture) might be regarded as perfectly normal in Japan. And staying within the United States for the moment (microlevel culture), behavior that is considered acceptable in a hockey game might not be acceptable in the boardroom.

Booker T. Washington wrote that “character, not circumstance,” makes the person. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “No change of circumstances can repair a defect of character.” While character makes for a good story or poem, in reality we are less shaped by character traits than we think, and more than we realize by the circumstances that life deals us—and our responses to those circumstances. It would be nice to be able to grade these circumstances from severely deleterious to benign, but what makes that impossible to do is individual differences in the way we respond to things. Some children who were (or felt) abandoned by their parents grow up to be well-adjusted, do-gooding members of society; others become axe murderers. Resilience, grit, and gratitude for the small things in life (“at least I still have food to eat”) are personality traits that are unevenly distributed in the population.

We think of our genes as influencing physical traits, like hair color, skin color, and height. But genes also influence mental and personality traits, such as self-assuredness, a tendency toward compassion, and how emotionally variable we are. Look at a room full of one-year-olds and it is apparent that some are more calm than others, some more independent, some loud, some quiet. Parents with more than one child marvel at how different their personalities were from the start. I carefully referred to genes influencing traits because the effect of genes is not chiseled in stone. Your genes don’t dictate how you’ll be, but they do provide a set of constraints, limits on how your personality will be shaped. Genetics is not an edict—the traits that our genes contribute to still need to navigate the twisty and unpredictable roads of culture and opportunity. Complex traits are best described as emergent properties that you cannot read in any one gene, nor even in a large set of genes, because how the genes express themselves over time is critical to the development of the trait as a social reality.

Genes can be present in your body but in a dormant state, waiting for the right environmental trigger to activate them—what is called gene expression. A traumatic experience, a good or bad diet, how and when you sleep, or contact with an inspiring role model can cause chemical modifications to your genes that in turn cause them to wake up and become activated, or to go to sleep and turn off. The way the brain wires itself up, both in the womb and throughout the life span, is a complex tango between genetic possibilities and environmental factors. Neurons become connected whenever you learn something, but this is subject to genetic constraints. If you’ve inherited genes that contribute to making you five feet tall, no amount of learning is likely to get you into the NBA (although Spud Webb is five foot seven and Muggsy Bogues is five foot three). More subtly, if your genes constrain the auditory memory circuits in your brain—perhaps because they favor visual-spatial cognition—you’re unlikely to become a superstar musician no matter how many lessons you take, because musicianship relies on auditory memory.

One way to think about gene expression is to think of your life as a film or multiyear TV series. Think of your DNA as the script: the set of instructions, dialogue, and stage directions for all the participants in the film. Your cells are the actors. Gene expression is the way that the actors decide to express that script. The actors may bring a certain interpretation to those words, based on their experience, and might surprise even the writers.

And, of course, the actors interact with and play off one another, for better or for worse. Jason Alexander, the actor who played George Costanza on Seinfeld, complained about how difficult it was to work with Heidi Swedberg (who played George’s fiancée, Susan). “I couldn’t figure out how to play off of her. . . . Her instincts for doing a scene, where the comedy was, and mine were always misfiring.” Julia Louis-Dreyfus and Jerry Seinfeld had similar complaints and reportedly said that doing scenes with her was “impossible.” But the chemistry between Alexander, Louis-Dreyfus, Seinfeld, and Michael Richards (Cosmo Kramer) was palpable, making Seinfeld the most successful comedy series in history.

Your genes, then, give you a kind of life script with only the most general things sketched out. And from there, you can improvise. Culture affects the ways you interpret that script, as do opportunity and circumstance. And then, once you interpret the script, it influences the way others respond to you. Those responses in your social world can change your brain’s wiring and chemistry, in turn affecting how you’ll respond to future events and which genes turn on and off—over and over again, cascading in complexity.

The second feature in the triad, culture, plays an important role in our understanding of traits. Humility is more valued in Mexico than in the United States, and more valued in rural Wisconsin than on Wall Street. Polite in Tel Aviv might be thought of as rude in Ottawa. The terms we use to describe others are not absolutes; they are culturally relative—when we describe differences in personality traits, we’re necessarily talking about how an individual compares to their society and to their societal norms.

Family is a microculture, and traditions, outlook, political and social views differ widely, especially within large industrialized countries. Go door to door in any town or city and you’ll find a wide range of attitudes about things as mundane as whether friends can just drop by or need to schedule in advance; how often teeth should be flossed (if at all); or whether TV and device time are regulated. And these unique family cultural values map onto particular personality traits: spontaneity, conscientiousness, and willingness (or at least ability) to follow rules. Culture is a potent factor in who we become.

The third part of the developmental triad is opportunity. Opportunity and circumstance play a larger part in behavior than most of us appreciate, and they do this in two different ways: how the world treats us, and the situations we find (or put) ourselves in.

Fair-skinned children burn more quickly in the sun than dark-skinned children and so may spend less time outdoors; skinny children can explore the insides of drainage pipes and the tops of trees more easily than heavy children. You may start out with an adventure-seeking personality, but if your body won’t let you realize it, you may seek other experiences, or adventure in less physical ways (like video games—or math).

Apart from these physical features, we all play roles, in our families and in society. The eldest child in a multichild household tends to take on some of the parenting and instruction of the younger ones; the youngest child may be relatively coddled or ignored, depending on the parents; the middle child may find herself thrust into the role of peacemaker. These factors influence our development, but again, as with genes, they are not deterministic—we can break free of them to improvise, to create our own futures, but it takes some effort (and for some, a lot of false starts, failures, and therapy).

How the World Treats Us

You might assume that identical twins end up with similar personalities just because they share identical (or near-identical) genes. But it might also be due to the fact that, to some extent, the world treats people who look alike in similar ways. People generally react with certain biases to the way you look, and by the time you were twelve or so, you probably recognized a pattern in how others reacted to you. Skin color, weight, and attractiveness are key determinants of how people are treated by teachers, strangers, and, unfortunately, the police. In one study of St. Petersburg, Florida, police department operations, male, nonwhite, poor, and younger suspects were all treated with more physical force, irrespective of their behavior.

Suppose there is something about your face and physique that makes you look mean—a certain way that your eyebrows curl downward toward your eyes, a squinty look to your eyelids, deep creases around your mouth—what is colloquially known as “resting bitch face.” According to The Washington Post, actress Kristen Stewart is the poster child for it, and Anna Kendrick is a self-described sufferer. (It applies to males as well, including Kanye West.) You may find that people are wary around you and even fear you. You may be kind and gentle on the inside, but after a lifetime of being misjudged, of people treating you suspiciously, you could turn cold in your social interactions, a real-life Shrek—the ogre who looks mean and frightens people but has a heart of gold.

One way this has been studied experimentally is to look at inter-rater agreement. Participants in an experiment meet strangers, or view photographs or videos of strangers, and then have to describe those strangers using a range of personality terms. The assumption is that, if you don’t know someone, your judgments of them will be based on their physical appearance—the particulars of their face, body type, dress, and body language. Studies like these go back to the early work in the sixties of Lew Goldberg at the University of Oregon and the Oregon Research Institute. These studies found consistent agreement across a variety of personality traits, such as sociable, extraverted, good-natured, responsible, calm, conscientious, and intellectual just based on what someone looked like. There is far less consistency in judgments for other terms such as agreeable, neurotic, and emotionally stable.

Of course, a bunch of strangers agreeing that someone is responsible doesn’t make them so. All that these experiments show is that when we interact with strangers, we bring some social-psychological baggage. The consensus about that baggage suggests that people within a culture share beliefs about how personality traits are linked to physical characteristics. When participants’ ratings of themselves were compared to the strangers’ ratings, some terms show high agreement, especially sociable and responsible. And although our self-perceptions are often flat-out wrong or distorted by ego needs, sometimes they are accurate—the problem is, we don’t know which times.

The culture we live in has a great deal of influence on how we categorize and evaluate traits. A body type that one culture finds threatening another might find nurturing; a face that one culture finds honest another may view as mocking.

The Search for the Magic Number

How do scientists study such a personal and seemingly subjective thing as personality? I wondered this for many years, until as fate would have it—opportunity, you might say—I met someone who was in the thick of figuring this out.

In 1980, I was looking to rent a cabin on the Oregon coast for a short while. I picked up the local newspaper, found an ad for one, and called the landlord on a pay phone. We met later that day. The landlord turned out to be Lew Goldberg—the psychology professor who had done much of the seminal work on measuring personality. He was leaving on sabbatical and wanted to rent out his weekend house. Although he ended up not renting to me—he chose an older, more financially stable renter—we ended up becoming friends. He introduced me to Sarah Hampson, who was his research colleague at the Oregon Research Institute. The mere fact that I got to know Sarah and Lew speaks to their gregariousness and their openness to meeting new people, even a young, ignorant student like me.

Lew doesn’t usually like talking about himself. He is outgoing and enthusiastic, but modest. After we had known each other for a while, I got him to talk about his work in measuring personality. Lew began by asking, “How would you study personality?” (You might stop for a moment and think about this before reading further.)

I thought: Maybe you could put somebody in a brain scanner and show them pictures of homeless people asking for money. If the part of the brain that’s responsible for feelings of generosity becomes excited, you might infer the person is generous, and if that same part of the brain is repulsed, you might infer they’re stingy. But how do we know which part of the brain is the “generosity” region? The truth is we don’t, and if we were to set about discovering that, we’d have to start out with generous people in order to locate that brain part. So we’re left back where we started: How do you know if someone is generous?

Maybe you could put them in a situation where they have an opportunity to demonstrate generosity. For example, on their way to your office, they pass by a homeless person and you secretly watch what they do.

There are three problems here, though. First, a person could be generous in a whole lot of situations but not the one you’re observing. Imagine someone philanthropically minded who prefers to donate to established charities. That person may have given a thousand dollars to a homeless shelter just yesterday, and another thousand dollars to a soup kitchen, and more money to the Red Cross, Oxfam, Habitat for Humanity, and United Way. Yet that person might fail your test. Or maybe the person just had their wallet stolen and doesn’t have any money to hand out today, although on any other day they would have given.

Second problem: How do you distinguish personality traits that might be triggered by the same scenario but are different? A person might not be generous but the scenario triggers something that looks like it: compassion—maybe this particular homeless person reminds her of her dear, departed sister, causing her to reach into her wallet for a few loose dollars. Or maybe due to a brain injury, a man lacks impulse control and simply can’t say no to any request of any kind—again, he’s not what you might conventionally consider generous; he simply appears that way in the particular circumstance you’re viewing.

Third problem: The sheer number of possible traits that a person can have would mean that we’d have to experiment on thousands of behaviors, making the research unwieldy and impractical. There must be an easier way.

I was not able to figure out this problem myself, but Lew had an elegant answer. He starts with an assumption, first popularized by Sir Francis Galton in the 1800s. Here’s Lew:

Let’s assume that those individual differences that are of the most significance in the daily transactions of persons with each other will eventually become encoded into their language. This is the lexical hypothesis. The more important such a difference is, the more will people notice it and wish to talk about it, with the result that eventually they will invent a word for it, such as those nouns (e.g., bigot, bully, fool, grouch, hick, loafer, miser, sucker) and adjectives (e.g., assertive, brave, energetic, honest, intelligent, responsible, sociable, sophisticated) that are used to describe persons.

Is Lew’s assumption true? Maybe not. But it’s a good starting point. Maybe there are some personality traits not captured in words, either because they are relatively rare (in which case we don’t need to worry about them now) or because they represent things that we’re uncomfortable talking about (in which case we need to create different assessment instruments). Let’s assume that the lexical hypothesis doesn’t mean we’ll identify every single personality trait possible, only that we’ll get most of the really important ones.

If you’re thinking that such terms might be culturally dependent—consistent with the triad of the developmental approach—you get a gold star (and, at least based on this example, you are clever, intelligent, and sophisticated). The cultural dependence might be obvious with a term such as hick. In a remote, closed community that doesn’t interact with outsiders, it would be difficult to imagine calling someone a hick or a bigot. Those seemingly depend on living in a more urbanized culture with opportunities to contrast city folk with country bumpkins, and tolerant, open-minded people with bigots. Similarly, a strictly monogamous society might not need a word for bigamy, and a society that stresses communal ownership of all property might not need a word for thief.

The possibility that personality traits are influenced by culture doesn’t doom the enterprise of measuring them—it all depends on what you want to use the information for. If you want to understand the personality traits that people exhibit in your own culture, or how they might change across the life span for you and your friends, there’s no problem. If, like some cross-cultural psychologists, you want to understand how personality varies from one culture to another, or if there are personality universals that show up in all cultures, then you take whatever tests you’ve come up with and administer them to as diverse a range of humans as possible. As Lew says:

The more important an individual difference is in human transactions, the more languages will have a term for it.

And so intrepid researchers, explorers of the personality domain, have gone off and studied the languages of diverse cultures from around the globe. Consider one type of individual difference, mental illness. It seems rather important to know whether a person you’re interacting with is sane, rational, and emotionally stable, or hears voices in their head. It turns out that peoples as diverse as the Inuit, in northwest Alaska; the Yoruba tribes of rural Nigeria; and the Pintupi aborigines of central Australia, who until a generation or two ago lived like Paleolithic hunter-gatherers, have words in their languages for these important personality descriptors. Furthermore, there is very little that is distinctive culturally in these societies’ attitudes and actions toward the mentally ill. Even words for more common and minor forms of mental illness, such as anxiety and depression, are found throughout the world.

Once scientists figured out how to measure personality, and how to describe people, another problem arose. There are thousands and thousands of different words used to describe personality traits—in English, there are 4,500 of them in Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, and more than 450 in current and common use. The sheer number can make a science of trait descriptions unwieldy—difficult to summarize, talk about, or make predictions with. This was one of the first “big data” problems, decades before there was Facebook or climate change data to analyze.

What scientists typically do with such mounds of data is to use mathematical techniques for data reduction, merging similar items into the same category or dimension. Doing so can allow us to discuss the data using a shorthand. We don’t discard the original data, so we can always go back to it.

Consider by analogy the shorthand we use to talk about spatial location—where people and things are in the world. We could use a three-dimensional coordinate system, such as latitude, longitude, and height above sea level, and for some things we do. But it is a cumbersome system that provides more information than we usually need. Instead, we divide the world into continents, countries, cities, neighborhoods, and so on, and this is usually enough.

Suppose you’re trying to schedule a meeting with people in your Houston-based organization and you haven’t been able to reach Terry. Briana says, “Oh, Terry is in Europe for the next couple of weeks.” That’s really all you need to know—you don’t need to know if he’s in Portugal or Macedonia, or if he’s staying on rue des Capuchins in Lyon, but presumably you could find out his exact location if you wanted to FedEx him some meeting notes—or maybe you only need his email address. And just because we’ve described Terry’s location simply as Europe doesn’t mean we’ll confuse Terry’s location with that of other people or things in Europe. If Doug says, “Oh—my cousin’s suitcase was just sent to Europe by mistake; maybe Terry will run into it there,” we see the folly: Europe is big. And so it goes with personality descriptions.

Even if we could find a way to summarize personality descriptions, to give us a shorthand for talking about them, it wouldn’t mean that everyone who is included in a personality description category is alike. But there may exist broad and meaningful trends we can talk about that, in general, distinguish a North American temperament or outlook from, say, an Asian or African one, without losing sight of individual differences and variability. And personality traits fall along a continuum: We can use modifiers to say that a person is more or less charming, more or less grouchy, more or less European.

Dozens of researchers spanning several countries set about trying to understand the best way to organize personality terms, to create a useful taxonomy. Ideally, whatever system we come up with would work across languages and cultures, which would greatly facilitate comparisons. It took more than fifty years for scientists to come to a consensus about this.

One prominent scientist argued for twenty to thirty dimensions; several others for two. Some argued for five or thirteen. Our friend Lew Goldberg initially gravitated toward a three-factor (three-dimensional) model proposed by psychologist Dean Peabody, rejecting the five-factor model, now known as the Big Five. “To my scientific tastes,” Lew said, “the Peabody model was elegant and beautiful, whereas the five-factor structure was a nightmare: All of the Big-Five factors but the first, extraversion, were highly related to evaluation [good-bad], meaning that they weren’t truly independent dimensions.” From roughly 1975 to 1985, he worked on collecting and analyzing data from a variety of sources to support the Peabody three-factor model, but no matter what he did, a five-factor model emerged from the analyses. Lew appealed to Dean Peabody to set up an experiment that would help them choose between three and five dimensions, something they designed together. When the data came in, they published a paper together showing that five dimensions comprised a more useful system (and it incorporated the original Peabody three). Goldberg became a reluctant convert, as did Peabody himself.

This never would have happened if Goldberg and Peabody had not been collaborative, open to new experience, agreeable, and at least slightly extraverted.

Collaborating with someone you disagree with represents a scientific ideal. When two or more researchers who are pursuing different theories, and who disagree with one another, decide to work together, the results can transform a field. Today many consider Lew the father of the Big Five personality categories. There have been cross-cultural replications in dozens of languages and cultures, including Chinese, German, Hebrew, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, and Turkish. As you might expect, some minor differences emerge in disparate cultures, but the Big Five remain the best description.

The Big Five dimensions are:

-

Extraversion

-

Agreeableness

-

Conscientiousness

-

Emotional Stability versus Neuroticism

-

Openness to Experience + Intellect (also called Imagination)

Each of these categories includes many dozens of individual traits. As you can see, there has been some controversy around what to call the last one, but don’t let that bother you—it is a well-defined dimension that includes a number of traits that cohere in real life.

EXTRAVERSION includes talkative, bold, energetic, and their opposites, quiet, timid, and lethargic. People who score high on the Extraversion dimension tend to be comfortable around other people, start conversations, and don’t mind being the center of attention.

AGREEABLENESS includes warm, cooperative, generous, and the opposites cold, adversarial, and stingy. People who score high on this dimension tend to be interested in other people, sympathize with others’ feelings, and make people feel at ease.

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS includes organized, responsible, careful, and practical, and the opposites disorganized, irresponsible, sloppy, and impractical. People who score high on this dimension tend to be prepared, be diligent, pay attention to details, and do what they say they will do.

EMOTIONAL STABILITY includes stable, contented, and at ease, and unstable, discontented, and nervous. People who score high on this dimension are not easily bothered by things, are relaxed, and don’t change their moods a lot.

OPENNESS (also called INTELLECT and IMAGINATION) includes curious, intelligent, and creative, as well as uninquisitive, dumb, and uncreative. It includes cognitive and behavioral flexibility. People who score high on this dimension are quick to understand things, have a vivid imagination, and like trying new things, new restaurants, and going to new places. It is separate from intellectual ability but speaks to a propensity to enjoy intellectual, cultural, aesthetic, and artistic experiences.

If you want to sound like a personality researcher, you can use the shorthand of the factor numbers, such as, “Oh, that Nancy is very low on Factor II,” or, “I think you should promote Stan in accounting—he’s high on Factors II and III.”

The drive to organize people’s traits into categories is ancient; astrology is one such attempt to assign personalities to people systematically, depending on when they were born. While it is still popular throughout the world, it has no scientific basis. Sure, you may know a Capricorn who is stubborn, but statistically, you’re just as likely to find stubborn Leos, Libras, and Sagittarians.

One point that often gets confused is that people tend to think of the Big Five as a typology (the extraverted type, the neurotic type, etc.). That’s not the case—it’s the configuration (or profile) of the five factors that represents someone’s personality. Just as we can describe physical objects in terms of length, width, and height, the Big Five framework allows us to describe human personality in terms of the five factors. Proponents of the Big Five never intended to reduce the rich tapestry of personality to a mere five traits. Rather, they seek to provide a framework in which to organize the myriad individual differences that characterize human beings. This organization reveals a great deal about things that have historically been important for humans to know about one another.

Factor I. Is Jason active and dominant or passive and submissive? (Can I bully Jason or will Jason try to bully me?)

Factor II. Is Mari agreeable or disagreeable? (Will my interactions with Mari be warm and pleasant or cold and distant?)

Factor III. Is Letitia responsible and conscientious or negligent and erratic? (Can I count on Letitia?)

Factor IV. Is Hannah crazy or sane? (Can I predict what Hannah will do, and will her actions make sense to me?)

Factor V. Is Felix smart or dumb? (How easy will it be for me to teach Felix? Is there anything I can learn from him?)

So What?

What does all this mean for us, people who are interested in the science of aging? The Big Five gives us a universally recognized structure for organizing what would otherwise be an unwieldy number of traits.

Whenever genes, situations, or therapy changes our personalities, they must do so by changing the brain. In that sense, all personality differences are biological, regardless of whether they are influenced by genetics or not, because they must go through the brain. These neurobiological changes are accompanied by chemical changes in the brain. As an example, assertiveness, competitiveness, dominance, and belligerence all are influenced by testosterone across genders. Higher levels lead us toward aggressive behaviors; lower levels lead us toward politeness. Testosterone levels are affected by the triad of factors—genes, culture, and opportunity. Situations such as a successful hunt, driving a fast car, being in the public eye, or being in charge of a large number of people can increase testosterone levels. The normal process of aging tends to lower them. A typical professional career trajectory finds one gaining more power as one gets older—this can compensate for biologically lowered levels of testosterone in some individuals.

Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and Emotional Stability can be thought of as reflecting a tendency toward reducing unwanted drama in our lives, and evidence is mounting that these are influenced by serotonin. Openness and Extraversion reflect a general tendency to explore and engage with possibilities, and these appear to be influenced by dopamine. Drugs that increase dopamine can cause us to want to explore more and engage in riskier behaviors. Low levels of serotonin are associated with aggression, poor impulse control, and depression, and drugs that improve serotonergic function are often prescribed to treat these.

The structure of genes has also been shown to influence personality. Alterations to the gene known as SLC6A4 are associated with neuroticism-related traits including anxiety, depression, hopelessness, guilt, hostility, and aggression. Other genes with hard-to-pronounce names are associated with self-determination and self-transcendence and with novelty seeking. The novelty-seeking genes are involved in dopamine regulation. An active area of research is dedicated to mapping these kinds of interactions between genes, brain, neurochemicals, and personality.

Temperament versus Personality

Babies are born with certain predispositions—a pattern of individual differences in how they react to different situations, as well as the regulation of those patterns. In babies and children, these patterns are usually called temperament, whereas in adults these patterns are called personality. Temperament and the young child’s early life experiences contribute to growing a personality. That personality will be based on the child’s developing views of self and others as they are shaped by experience. A child who grows up in an environment with many dangers and hazards will surely view the world differently than one who is nurtured and sheltered. The fascinating thing is that personality development doesn’t always go the way one might predict.

You might think that a child who grows up in a dangerous environment will learn to be fearful and will develop a fearful, anxious, and perhaps neurotic personality. This can certainly occur. But a different child, with different genetic predispositions, uterine environment, and parenting may become fearless, brave, and challenge seeking. Temperament becomes personality as the child develops its own values, attitudes, and coping strategies. And it is biologically based, linked to, but not completely determined by, an individual’s genetic makeup.

Temperament is typically measured in young children along dimensions that parallel temperament in animals. These include surgency (activity level, or Factor I), sociability (Factor II), self-regulation (Factor III), and curiosity (Factor V). These have been found to correlate highly with the Big Five. Factor IV, whether a person is crazy or sane, is more difficult to assess in animals and infants. (Although at times, I think every parent of a two-year-old thinks their child must be crazy. And, of course, they are! Babies are entirely egocentric, true psychopaths, who don’t care about anyone but themselves.)

Age-Related Personality Changes

There are a number of ways in which the natural aging process itself tends to cause some personality changes. In a meta-analysis of ninety-two research papers, covering the life course from age 10 to 101, 75 percent of personality traits studied changed significantly after the age of forty and well beyond sixty. (These tendencies will not apply to all people. Some people don’t change at all, and some change in ways that contradict statistical trends.) Some changes result from diseases and injuries, such as Alzheimer’s, Pick’s disease, stroke, or concussion due to falling.

So what are the trends? Older adults tend to be better at controlling impulses; that is, they’re better at self-control and self-discipline and tend to be better at rule-following than young adults—traits that have to do with Factor III (Conscientiousness). Self-control increases steadily every decade after the age of twenty. Some of this has to do with the development of the prefrontal cortex, which continues through the early twenties, and yet we see additional age-related dispositional changes in impulse control that we haven’t found a cause for yet.

Flexibility—your ability to easily adapt to changes in plans or to your environment—decreases steadily in every decade after twenty. With age, men typically show increased emotional sensitivity, and women experience decreasing emotional vulnerability. As you might expect—and may have experienced yourself—Openness increases around adolescence, but then declines with age.

In addition, older adults are generally more concerned with making a good impression and with cooperating and getting along with others—Agreeableness increases substantially. They show increased Emotional Stability and calm as well. I’m sure you can think of exceptions—remember, these are just averages. One of my favorite pictures in social neuroscience comes from a study of nearly 1 million individuals from sixty-two countries, showing how consistently Emotional Stability, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness increase with age. The chart for one country, Canada, is shown on the next page.

Conscientiousness, Openness, and Extraversion decreased during old age, whereas Agreeableness and Emotional Stability increased substantially. Similarly, these results suggested that the initially increasing levels of Conscientiousness may in fact start to decrease following the age of fifty. Individuals appear to become more self-content in old age, an aspect of Emotional Stability called the La Dolce Vita effect: the sweet life. Older adults are more content with what they have, more self-contained and laid-back, less driven toward productivity. Mood disorders, anxiety, and behavioral problems decrease past age sixty, and onset of these problems after that age is very rare.

Older adults are less likely to engage in risky or thrill-seeking behaviors and tend to be more morally responsible and less open to new experience. In terms of the Big Five factor model, older people show declines in Extraversion and Openness and increases in Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Agreeableness.

Some of these age-related changes are based on microculture and opportunity—the social roles that we and our cohort of friends invest in during earlier life stages. By late adolescence and early adulthood, people become more independent and begin investing in their education and career. Success in these domains depends very much on being reliable, dependable, and competent. Prior to this period, there is probably less need to behave conscientiously because parents and institutions are in place to guide people through life. For some, Conscientiousness declines after retirement not because the brain has changed but because there is less need to be a hardworking, driven personality—it seems okay to loosen one’s grip a bit and enjoy la dolce vita. And many transitions in social roles occur in older adulthood, when we might become grandparents, retire from full-time work, or take up new hobbies. Health challenges present us with a stark choice and an opportunity to mold our personalities: Am I someone who folds up and gives in, or do I double down, embrace resilience and optimism, and try to make the best of the time I have left?

Optimism predicts longevity. But too much optimism can lead to bad health outcomes. If you’re unrealistically optimistic, you might not have that dark spot on your forehead checked for cancer; you might ignore the fact that you’ve been putting on ten pounds every decade since you were forty, figuring it will all work out just fine. Although optimism is a crucial part of disease recovery, tissue repair, and so on, it needs to be tempered with realism and conscientiousness.

Illness often causes us to change our personalities. In Sarah Hampson’s work on people with type 2 diabetes, it was not uncommon for people to say that the onset of this disease made them take better care of themselves. Aspiring to a healthier lifestyle may thus lead to personality change—an increase in self-control, methodicalness, and conscientiousness.

The Role of Role Models

Role models show us we can step outside of who we are. We look at them and see the kinds of changes we want to make, the kinds of lives we want to lead—we see that what might have remained a dusty and dark secret aspiration is possible. They help us realize that we can become our own autobiographers—we can alter the story of our lives for better or worse. But one person’s inspiring role model might just be annoying to another person. That’s the reason that so many different voices grace this book. You may not agree with everyone’s politics or outlook on life, but these individuals are included to show the wide range of possibilities for staying healthy, engaged, and active in one’s later years, for—as Jane Fonda described it to me—aging gracefully.

Creating your own future is possible at any age. Julia “Hurricane” Hawkins is a native of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and a retired schoolteacher. She is a devoted gardener with an affection for bonsai trees. Hawkins took up competitive athletics for the first time at age seventy-five. She competed as a cyclist in the National Senior Games, winning bronze and gold medals. Twenty-five years later, she branched out, taking up running at age one hundred. Hawkins again competed in the National Senior Games at age 101, establishing the record for women one hundred and older in the hundred-yard dash at 39.62 seconds. She also competed in the fifty-yard dash against other runners as “young” as ninety, finishing in 18.31 seconds. Her secret? “Keep in good shape, try not to be overweight, get good sleep, and keep exercising and training.” However, she adds, “There is a fine line of pushing yourself and wearing yourself out. You don’t want to overdo it. You just want to do the best you can do.” In 2017, after winning the hundred-yard dash in the National Senior Games, she said, “I don’t feel 101. I feel about 60 or 70. You are not going to be perfect at 101, but nothing stops me.” A year later, at age 102, Hawkins set a new world record for running sixty meters in 24.79 seconds. “I just like the feeling of being independent and doing something a little different and testing myself, trying to get better.” In June 2019, at age 103, she won gold medals in the 50 and 100 meter races.

Testing oneself and trying to get better are themes that run through the inspirational lives of so many. At age ninety-three, the guitarist Andrés Segovia launched a new tour, and in one of his last interviews before his death at ninety-four he said that he still practiced five hours a day. Why, having accomplished so much in his life and being regarded as the greatest living guitarist, was he still practicing? “There’s this one passage that has been giving me a little bit of trouble,” he said.

The Netflix series Grace and Frankie, in its fifth season airing in 2019, stars Jane Fonda, eighty-two, and Lily Tomlin, eighty. Tomlin’s character, Frankie Bergstein, is a textbook case of someone with great openness—she smokes marijuana regularly, is a painter, and once hired a building contractor who lived in the woods behind a neighbor’s house. Fonda’s character, Grace Hanson, is set in her ways, emotionally cold, and conservative. In the second season, they start their own business, something that is completely new for the hippie-socialist Frankie, and in season four Grace starts dating a younger man, played by Peter Gallagher. What draws so many people to the show is the message that you can change in later life, you can try new things, and you can have fun doing it. “What Lily and I hear very often,” Fonda says, “is ‘It makes us feel less afraid of getting older. It makes us feel hopeful.’ . . . I left the [entertainment] business at age 50, and I came back at age 65. It’s been an unusual situation to re-create a career at that age. . . . One of the things that Lily and I are proud of—and want to continue with—is showing that you may be old, you may be in your third act, but you can still be vital and sexual and funny . . . that life isn’t over.”

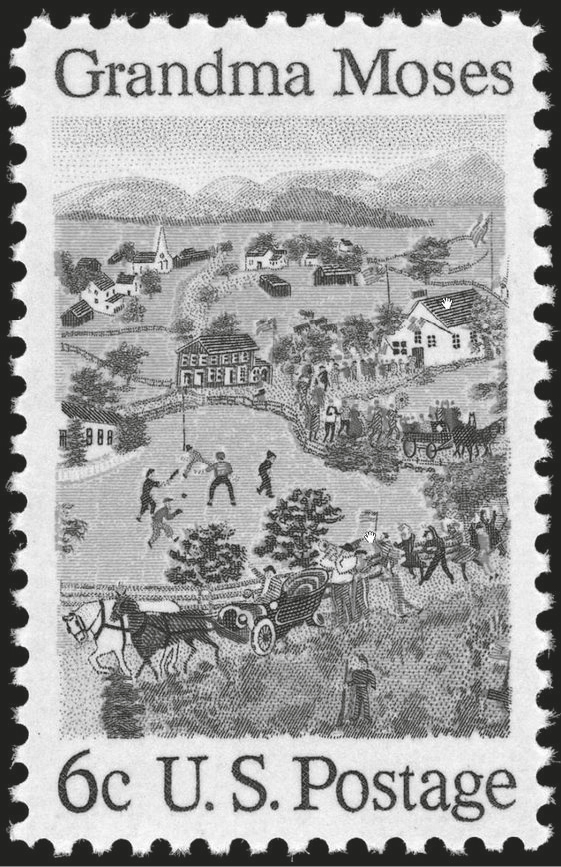

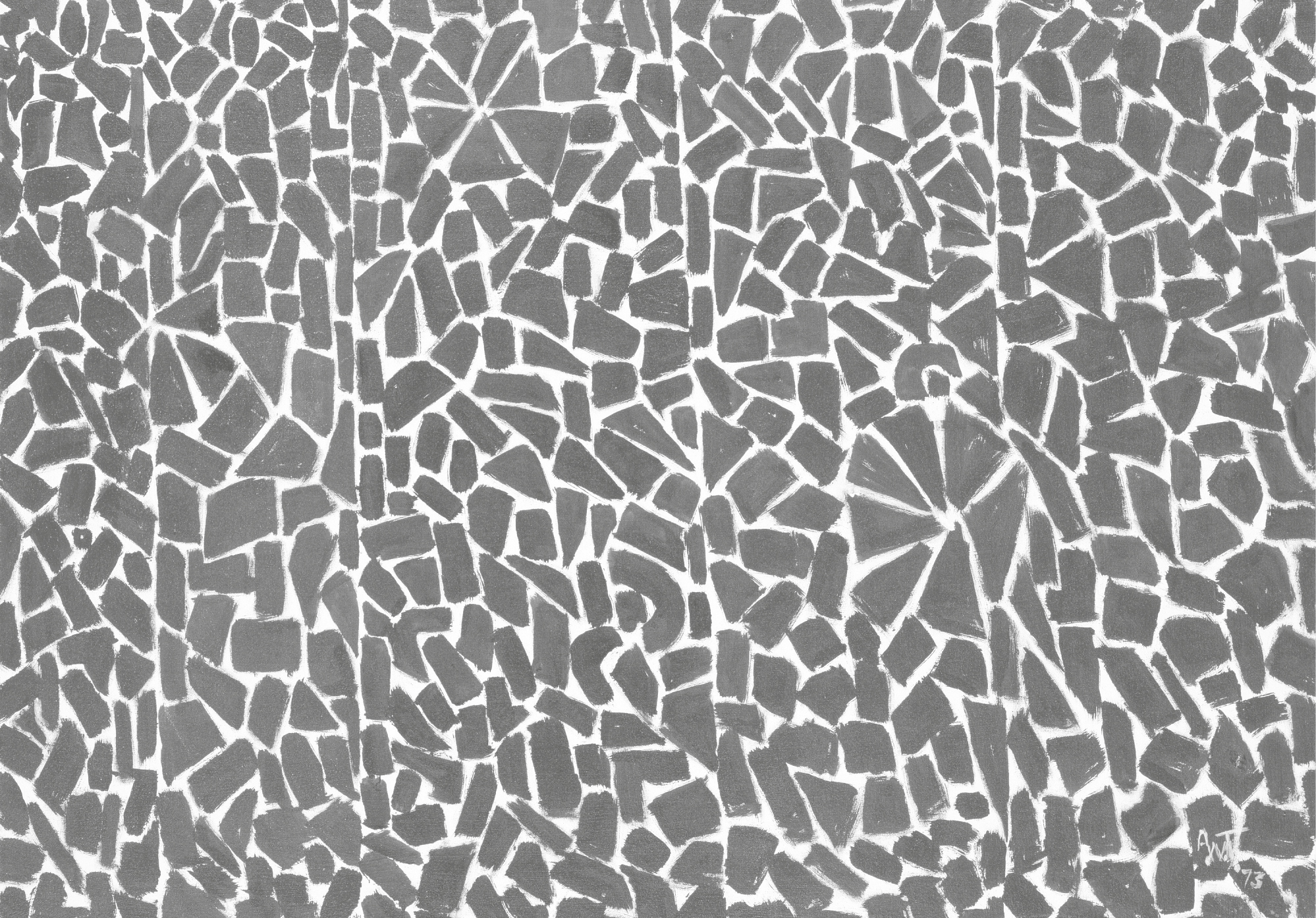

Anna Mary Robertson, better known as Grandma Moses, didn’t even start painting seriously until she was seventy-five, and continued until she was 101. Today her works are displayed at the Smithsonian and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, among others, and have sold for more than a million dollars. One of her paintings hangs in the White House and was turned into a commemorative stamp. She painted it at age ninety-one. Alma Thomas didn’t have her first art exhibition until she was seventy-five. She was the first African American woman to have a solo show at the Whitney, and now her works hang in the Smithsonian and the White House.

I’m reminded of another story, of a man who was born poor in Indiana in 1890 and whose father died when he was five. An unmotivated child, he dropped out of school in the middle of seventh grade and never went back. By age seventeen, he had already been fired from four jobs. He became a drifter, moving from one unskilled job to another, finding himself broke most of his life. If early childhood and young adult experiences were all there was to a life story, you could predict that his life would be characterized by one disappointment after another. Indeed, he appeared aimless and unfocused. Among other things, he found work as a steam engine stoker, farmhand, blacksmith, soldier, railroad fireman, buggy painter, streetcar conductor, janitor, insurance salesman, and filling station operator, but never managed to hold on to a job or to save any money. At age fifty, he started another doomed job, a roadside eatery in Corbin, Kentucky. The restaurant eked along and then finally gave its last gasp, going out of business when he was sixty-two. There he was, pushing retirement age, broke (again), and living out of his car. How many of us would give up at that point? He had never had a success in his life, and the life expectancy for a sixty-two-year-old in 1952 was just another 3.2 years.

One day he took an old family recipe and, imagining the potential of franchised restaurants, opened one in Utah with borrowed money. That might be the end of the story, except that his name was Harland Sanders, and the restaurant was Kentucky Fried Chicken, now known as KFC and one of the largest suppliers of food in the world. Sanders sold the company at age seventy-four for $2 million, about the equivalent of $32 million in today’s dollars. The company he conceived of at age sixty-two now has annual revenues of $23 billion and is known throughout the world. He continued advising the company and working as a brand ambassador into his nineties.

At age eighty-nine, Colonel Sanders was asked, “You don’t believe in retirement?” “No,” he answered adamantly. “Not a bit in the world. When the Lord put Father Adam here he never told him to quit at 65, did he? He worked into his final years. I think as long as you’ve got health, and ability, use it . . . to the end.”

Trying something new later in life, like competitive sports, business enterprises, or artistic endeavors, can dramatically increase both your quality of life and how long you live. Openness and curiosity correlate highly with good health and long life. People who are curious are more apt to challenge themselves intellectually and socially and reap the rewards of the mental calisthenics that result. They are also more likely to be interested and engaged, which makes them more fun to be around, and interacting with others socially is a good way to stay mentally agile and alert.

Conscientiousness

Perhaps the most important traits to foster and develop throughout the life span are those in Factor III, Conscientiousness. Conscientious people are more likely to have a doctor and to go see one when they’re sick. They’re more likely to get regular medical checkups and to reliably keep up with their professional, family, and financial commitments. This may sound like a mostly practical matter, but Factor III traits are highly correlated with a panoply of positive life outcomes, including longevity, success, and happiness. Conscientiousness has been linked to lower all-cause mortality. Conversely, lower childhood conscientiousness predicts greater obesity, physiological dysregulation, and worse lipid profiles in adulthood. To become more conscientious, one must change underlying cognitive processes such as self-regulation (controlling impulsive behaviors) and self-monitoring (noticing which circumstances lead to successful self-regulation and which circumstances sabotage self-regulation). If you wish you had more of these, a number of different methods have been shown to work for adults of any age, from cognitive behavioral therapy to David Allen’s book Getting Things Done.

A recent psychological study, published in the flagship journal of the Association for Psychological Science, corroborated what Charles Koch, CEO of one of the largest companies in the world, says: “I’d rather hire someone who is conscientious, curious, and honest than someone who is highly intelligent but lacks those qualities. Runaway intelligence without conscientiousness, curiosity and honesty, I learned, can lead to dismal outcomes.”

IQ, one’s intelligence quotient, is a familiar metric. Increasingly, so too is EQ, the emotional intelligence quotient, thanks in part to the popular writings of Daniel Goleman. Cognitive scientists now talk about a third metric, CQ, the curiosity quotient, and it predicts life success as well as, and often better than, IQ or EQ.

As you might imagine, there are limits to both Conscientiousness and Curiosity. Too much of either can cause trouble. Someone who is too conscientious might stray into obsessive compulsive disorder behaviors; it’s helpful to distinguish healthy conscientiousness from extreme rigidity or compulsion. Systemic conscientiousness, if it involves blind adherence to faulty rules, is also a problem, such as when the medical community recommends policies that can cause harm. Screening for prostate cancer with the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) biomarker is probably the most notorious case of causing significant harm to patients. Most men with elevated PSA levels will never develop symptoms of prostate cancer, but many have died or suffered serious health problems after receiving unnecessary treatment. The ratio of those helped versus harmed by PSA screening is around one in a hundred. Overdiagnosis is common in other “conscientious” cancer screenings as well.

Openness

Can too much openness lead someone to engage in risky, dangerous behaviors? Yes. John Lennon was famously open to new experiences and at one point considered an untested form of therapy that involved having a hole drilled in his skull. Amy Winehouse, who faced great difficulties with impulse control, died at twenty-seven from alcohol poisoning. Steve Jobs, also famous for his openness, pursued an untested treatment for his pancreatic cancer, and that openness—rather than a reliance on scientifically validated medical treatments—killed him.

Fortunately, our traits and personalities are malleable, like the brain itself. We can change. We can learn from our experiences. All of us have an internal monologue, a narrator in our heads keeping track of things such as “I’m hungry” or “I’m cold.” The internal narrator also tells us, “This is what I’m like—these are the things I like to do, these are the ways I respond to certain situations.” Knowing this about ourselves is the first step toward change, toward affirming that our past behavior does not necessarily determine our future behavior. Even models we learn about through the media can help us to make aspirational changes. And personal affirmations (“I am generous, I am kind”) can help us to become what we’re not. A famous old psychology experiment showed that people who act as if they’re happy end up being happy. The zygomatic facial muscle is what you use to smile when you’re genuinely happy. In one experiment people who forced a smile actually felt happier than people who forced a frown, just because that muscle was engaged. It turns out that the nervous system is bidirectional. It doesn’t matter whether the brain makes the mouth smile or the mouth makes the brain smile. So smile, think positive thoughts, and try new things. If you’re not feeling good, act as if you are. A cheerful, positive, optimistic outlook—even if it starts out fake—can end up becoming real.

Compassion

There is an inherent asymmetry in the amount and kind of information we have about ourselves versus what we know about others. You have unique access to your past actions and to your current mental states and motivations, but you do not have this level of access to others’ memories and states of mind (except in a good movie or novel). They have the same lack of access when judging you. Imagine you’re driving a fancy car and a homeless person walks up and asks for a dollar as you’re waiting at a stoplight. Imagine also that you don’t give it to him. He may conclude that you’re a tightwad. You may have wanted to help but not have had any cash on you. One behavior, two different interpretations.

One tangible thing that we can all do to avoid misjudging others is to exercise compassion, to allow for the possibility that you might be wrong in attributing a trait to someone’s behavior. Indeed, this is the core principle at the heart of both social psychology and the teachings of the Dalai Lama. “Compassion is the key to happiness,” he says. “We are a social species and our happiness is defined by our relationship with others.” The Dalai Lama believes this comes from the biology of our species, of the importance of social interactions to all primates. He tries to avoid feeling anger, suspicion, and distrust and instead practices patience, tolerance, and compassion. In addition, he avoids thinking of himself as privileged or special, and this increases his happiness a great deal:

I never considered myself as something special. If I consider myself to [be] something different from you, like, ‘I am Buddhist’ or even more [with haughty voice] ‘I am His Holiness the Dalai Lama’ or even if I consider that ‘I am a Nobel laureate,’ then actually you create yourself as a prisoner. I forget these things—I simply consider I am one of seven billion human beings.

Buddhism, like most of the world’s religions, teaches you how to change your personality. You may feel that your personality is fixed, inflexible, and was determined in childhood, but science has shown otherwise. In particular, studies since Bayley and Baltes have found that volitional (not disease-induced) personality change is possible at least through one’s eighties, in the three continents so far studied, North America, Europe, and Asia.

The compassionate attitude and outlook are also related to experiencing less stress. You can choose not to be stressy—or learn how—and this can save your life. The HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis is an endocrine system that controls the secretion of stress hormones (glucocorticoids) including cortisol. Exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids can be particularly detrimental for the aging hippocampus and is associated with decrements in learning and memory. Among the things that psychotherapy is best at, stress reduction is one of the most important things you can do for your overall health. And yet, there can be too much of a good thing. Too much stress reduction, like too much optimism, may cause you to ignore important health issues or to become unmotivated to work or seek social contact. Moderate amounts of stress impel us to do things—to exercise, eat well, and nurture our mental health by making friends and spending time with them.

Is a Good Personality Sufficient?

Curiosity, Openness, Associations (as in sociability), Conscientiousness, and Healthy practices are the five lifestyle choices that have the biggest impact on the rest of our lives. The first four are elements of anyone’s personality. The acronym they make is COACH, a term I use a few times in these pages and which comes ultimately from reading thousands of pages on aging research. I will return to its many implications in subsequent chapters. But one infamous aspect of aging does not fit into a personality trait: memory. It’s a topic that gets at the core of who we are and how we experience life. Many of us wouldn’t mind having someone else’s hair, maybe someone else’s intellect or emotional composure, but someone else’s memories? We’d cease being who we are. So what do we know about the brain basis of memory, and why does memory seem to be the first thing to go?