‘YOU PUNCH TOO hard, Bartley,’ said old Wogga Wood. ‘I’m scared of you killing someone.’

I shrugged and resumed thumping the heavy bag. It swayed and shuddered, its rope creaking against the ceiling hook. Wogga stood back, a water bottle in one hand and a sweaty towel in the other. Two young boxers tip-tapped skip-rope beats on the wooden floor of the gymnasium. Others slid around the roped ring, shadow-boxing. Double doors connected the training area to an adjoining bar, where a line of men stood drinking beer. They would open the doors so the drinkers could watch the crazy, red-headed gypsy fighter.

I pulled a crowd every night. I could hit the light bag so hard it would fly up almost to the horizontal. Sometimes Wogga would hold the heavy bag still and I would drive dents into it with my gloved fists, the sweat running off my brow. My power was natural; I didn’t have to develop it.

I became a regular at Wogga’s gym when my family left Wales in 1963, the year John F. Kennedy was shot, and settled in Uttoxeter, a racecourse town halfway between Stoke-on-Trent and Derby. There was a plot at the back of a garage just off the town centre and the owner, Joe Phillips, let us pull our trailers on there. Travellers are often ostracised by townspeople but we soon made new friends. The locals could see that my parents were decent. Dad was always in suit, collar and tie and marched us to Mass every Sunday. At meal times everything had to be perfect: we had silver knives and forks and best Crown Derby. Dad wouldn’t have anybody in the trailer except family, close friends and special guests. He kept an old-fashioned biscuit barrel full of gold sovereigns. Occasionally he would take the lid off and show us. ‘There you are, son,’ he’d say. ‘I don’t need a bank account.’ Then he would squeeze the lid back on.

He was still selling carpets and painting barns. I helped but was also branching out on my own, learning to wheel and deal. Travellers are some of the best salesmen you’ll ever meet. They know psychology, how to appeal to people’s vanity or greed, how to plant a sprat to catch a mackerel.

Even more than dealing, I loved fighting. I had set my heart on boxing, though it almost cost me dear even before we had reached Uttoxeter. We had stopped for a while on a big pit bank near Telford and someone told me about a gym in Wolverhampton. I set off to find it, taking the train to Wolverhampton station and then asking the first group of men I saw where the boxing gym was.

‘Why? Don’t you know?’ said one of these men. He had a Geordie accent and an evil look in his eye; probably a collier come down for the work.

‘No, I’m a stranger here,’ I said.

‘Oh, you’re a stranger, are you?’

He pushed me in the chest. The other men came in a circle around me. I looked around for help but the street was dark and virtually deserted. I was only eighteen years old and they were grown men. Yet I felt that strange mix of energy and calm that always settled on me before a fight. Without warning I threw a hard straight left into the face of the first man. As he stumbled, I hit the man next to him with a right cross, then the man on his other side with a left hook. Both of them hit the deck. As the others stood there, unsure of what to do, I turned and walked away – fast. They didn’t come after me; I think they were too stunned.

I found the gym in the end but it wasn’t really to my liking – the training was a bit soft. I went there a few times but we left the area soon after for Uttoxeter. I went looking for a new gym and soon found Wogga Wood, a former booth boxer who had forgotten more about the fight game than most trainers will ever know. He coached at the Drill Hall in the coalmining town of Rugeley. The room was large and well equipped, though it stank of sweat, stale air and liniment. The Territorial Army were based next door and went through their drills there, doing hand-to-hand combat and bayonet practice. Wogga trained some good fighters: his son Jackie won five National Coal Board championships when that title meant something in the amateur ring. One of the first things he did when I went in was to get Jackie, a light-heavyweight, to try me out but I already knew how to fight and more than held my own.

I loved it. I was soon training every Tuesday, Friday and Sunday, plus doing my roadwork every day at dawn. I liked sparring best of all: getting in there and fighting. I would do three rounds with one boxer, three with another, three with another and three with another: twelve rounds. Most pros wouldn’t do that, unless they had a title fight. Wogga took me under his wing and after every training session insisted that I drink two bottles of Guinness to ‘build me up’. We would sit in the bar with our glasses of stout in front of us and talk about boxing for hours: hooks, jabs and footwork, great fighters, famous fights. I was entranced. A bomb could have gone off next to us and I wouldn’t have noticed.

I would have a dozen or so fights for the boxing club. I did lose the odd bout – one I remember to a man called Denis Briggs – but I learned quickly and still have a ‘Best Boxer of the Night’ trophy from one tournament. As I got better – and bigger – it became harder to find opponents. One slick stylist I fancied my chances against was a young black man from the Midlands called Fitzroy Johnson. We were matched to box but he refused when I weighed-in five pounds heavier than him. Later he turned pro and, as Bunny Johnson, won the British and Commonwealth heavyweight titles.

My toughest fight came when I was twenty-two. I was due to fight a man at the Metropolitan Club in Small Heath, Birmingham, but he didn’t turn up, so they put me in with someone called John Mulroy. Our bout was late on, about midnight, and I was so confident that I fell asleep in the dressing room. Wogga came in and roused me. ‘I’ve just seen your opponent,’ he said. ‘He’s got green velvet boots on.’ This Mulroy was an Irishman, had boxed for his country and had a big Birmingham-Irish contingent there to watch him. I had a load of Irish and English travellers there to see me. Suddenly the atmosphere was red hot.

I bounced into the ring like Ali, showboating, moving around, feeling the ropes, hamming it up. ‘He’s pissed as a newt!’ said one ringside spectator. Then I saw Mulroy. He was in his thirties, a fully-fledged man, and looked about six foot three. All of the Irish were going mad, roaring. It was bedlam.

We came out for the first round and I used the ring, swaying and making him miss. He was no mug: I always had a lot of time for amateurs because they were unpaid men, fighting for the love of it, not for money like some performing jotter (monkey). He was also a southpaw, which made matters worse. He was long and rangy and started connecting, and I couldn’t resist getting drawn into a punch-up. Soon we were at it hammer and tongs. I caught him with some cracking right hands but he took them and hit back. He was one of the hardest punchers I would ever meet, including bareknuckle. He hit me so hard with one left cross that I thought the branch of a tree had fallen on my head. I loved it because it was a rough, unorthodox fight.

By the end of round two we had been through the mincer. I went back to my stool and said to my trainer, ‘Just roll them gloves up.’ He pulled them right up so my knuckles were tight against the padding. The bell rang for the final round. This was war now.

‘Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,’ shouted our Sam at ringside, mimicking Bundini Brown, Muhammad Ali’s sidekick.

Someone at ringside took umbrage. ‘Black your face before you come here and say that, mate,’ he shouted back.

Sam promptly started fighting in the crowd: him and Johnny Stevens against five or six men from Birmingham. A woman hit Johnny on the head with a stiletto heel. There was uproar. I could hear the commotion but couldn’t afford to take my eyes off Mulroy. He stepped back and grinned at me and I smiled. They say if a boxer smiles during a fight it is a sign of weakness but I can tell you that is not true: there was nothing weak about Mulroy. He ducked his head into my face. I gave him the shoulder. The ref tried to pull us apart and Mulroy punched me low. I hit him back, right in the foul protector. The ref was yelling. Chairs were flying at ringside. Sam had one man in a headlock and was punching another with his free hand. Someone jumped on the ring apron.

Suddenly there was a loud rending noise and the ring tilted sharply to one side; it had partly collapsed. I’m sure Sam was the cause of it. The referee had had enough. He waved his arms wildly and called the fight off. ‘Referee disqualifies both fighters for dirty fighting,’ read the back page of the next day’s Birmingham Post. They reckon we made history.

I stopped taking the gloved game seriously after that, although I would have a few more bouts over the years. I felt baulked by gloves and referees. I used to get butterflies before boxing but never before a bareknuckle fight. I just felt constrained by the rules. In the lanes, you are your own referee. It was also difficult to reconcile the travelling life with the strict training needed to be a good boxer. As I got older and was on the road more and more earning a living, it was impossible to put in the hours at the gym. Occasionally I would stop in an area and if there was an amateur show on I would go along to see if they had an opponent free. They wouldn’t ask too many questions about licences and the like if you were a heavyweight; they’d put you on if they could, because the crowds loved to see two heavies. They might call it an exhibition to satisfy the ABA inspector, but it would be a proper fight. I had quite a few contests like that under aliases, particularly around Norfolk, where the money was good for barn painting. It was all corn there – you wouldn’t see a cow or sheep.

*

I NEVER DARED tell Wogga that I was using his boxing training to prepare me for bareknuckle fights – he would have gone mad. But by this time my reputation as a barefist fighter was spreading and young men were coming to challenge me. One morning my father was sitting in the trailer, figuring out where he was going to go hawking that day, when a wiry, dark-skinned lad showed up in the yard with his dad.

‘My son can beat your son,’ said the dad.

‘I’m a match for Bartley, I can beat him any time,’ chimed in the lad.

Our fathers started haggling. ‘He’ll fight him for a hundred pound,’ said the lad’s dad and pulled out a wad of notes. You could buy a good secondhand car in those days for that. Down went the money and my dad nodded me outside into the yard. We shaped up. I let fly with half a dozen machine-gun punches and laid the lad out right there in the yard – he barely had time to throw a punch. We had no need to go hawking that day.

I was gathering a new gang around me. One was a young Uttoxeter lad called Dave Russell, who we called ‘Old Soldier’ because he had been in the army for a bit. He was in his late teens and was unhappy at home: his father was very hard on him and Dave couldn’t take it any more. One night he had been fighting in town and came home with blood on his collar. ‘So you think you can fight?’ said his dad, and thumped him. For the first time, Dave hit him back, and that was pretty much the end of their relationship.

Dave was working in a biscuit factory carrying hundredweight bags of flour and emptying them into a sieve. He had no mask to wear and was covered in muck all the time. I pulled up there to see him one day and he looked ill.

‘How much are you getting for working in there?’ I asked.

‘Three pounds a week.’

‘You can sit in my van, I’ll give you three pounds a week for nothing.’

I got Dave an old trailer to live in next to us. He found my dad as strict as his but fair with it, and my mam kept him fed. He became a sparring partner for Sam and me. Dave could take no end of punishment without complaining. We were always doing trials of strength. I would ask Dave to hit me in the stomach as hard as he could and try to take it without flinching. Sam and I also would get a wooden ladder, lay it across two boxes and ask people to lie on it, then we would lift them above our heads, using them as human barbells. They were frightened that we’d drop them but we never did.

Every morning at five o’clock we’d be up for a run. Then we would wash in cold water. Soldier Dave was used to his hot baths and my dad would bellow at him, ‘What are you, a man or a mouse? Get your clothes off and get washed.’ He used to inspect Dave, checking behind his ears.

The good food and outdoor life certainly seemed to do the trick. Our Sam grew into a living giant. He eventually topped six feet one, weighed eighteen stone and had an eighty-four-inch reach and nineteen-inch biceps. His fists were massive, sixteen inches around. He’d sit in the pub and put them on the table and people couldn’t help but look at them. Sam was also the toughest traveller I ever knew – I believe he was a better fighter than me, but he stood back because I was the oldest. In the boxing ring he would face his opponent square on, with his knees slightly bent, and nobody could move him back. Even I couldn’t take punishment like Sam. But he wasn’t a troublemaker, more a gentle giant.

We ate like horses; I think we were the butchers’ best friends. We’d see my dad walking down the road and he’d say, ‘Look what I’ve got for dinner today,’ and it would be a huge lump of beef wrapped up. My mother was a wonderful cook. Her pies were perfection. We ate plenty of fresh food and could live off the land like natives, though we were never into the traditional Romany fare of hedgehogs, or hotchy witchie. I would wade waist-deep into rivers to ‘tickle’ trout with my hands and could have half a dozen hanging from a V-shaped twig in no time, though I did it mainly for sport, as my dad made sure we never went short of food.

We hadn’t been in Uttoxeter long when I had a band of men working for me: my brothers Sam and John, Gandy Hodgkinson, Colin Morfitt, a top rugby player with a twenty-six-inch neck, Paul ‘Beaky’ Smith, a good boxer, my best pal Alan Wilson, Caggy Barrett, Noah Lock and Johnny Wheeldon. We stuck together in a big gang – all men, no women – and I kept the lot of them. We’d be in London for a week hawking, East Anglia for a month painting barns, then maybe over to Wales, up to Manchester and Liverpool to buy scrap, further on to the little Cumbrian town of Appleby for the horse fair, then maybe to Scotland or over to Ireland for another fair. We had ten trailers (caravans) and about twenty vans and we’d pull in on a lay-by or farm we knew and look for work. I had men painting Dutch barns and repairing roofs and tarmaccing roads.

I suppose we were pretty rough. You can imagine what people thought when they saw us all pulling in somewhere. There were always scraps and arguments and often we would put on the headlights of motors at night for men to settle an argument the travellers’ way. Once we were in the middle of Birmingham, having just weighed in a load of scrap, and Gandy and Colin Morfitt began arguing over a few pounds. I stopped the van and said, ‘If you want to fight, fight.’ They jumped out in a long line of traffic and fought in the road.

I was as wild as any of them. Once I even fought a badger and killed it and brought it back to the camp. My father went mad. ‘It’ll give you TB, get that away from there,’ he said. My dad and I still had our fallouts: we were two strong characters who both hated to back down. I was too big now for him to hit but I would never have laid a finger back on my dad. I regret every row we had, because we did love each other and I thought he was the best father in the world.

*

MANY GYPSY FIGHTERS are happy to be kings of their own patch. They never challenge people outside their own areas. That wasn’t good enough for me. It was my birthright to be champion of all of them, to do what my great-grandfather and grandfather and Hughie Burton had done.

In the mid-Sixties, I went to Norfolk with my Uncle Joe, pulling onto some common ground where other travellers were staying. We went out working and when we came back, someone had smashed the windows of our trailers. Uncle Joe warned me not to say anything because we were just two and were heavily outnumbered.

The next day, Uncle Joe was cooking a bit of tea outside when a man came across and started chatting. He seemed friendly enough. Soon a big, dark-headed fellow joined him. His name was Leefoy Price; the Prices are one of the best-known Romany breeds.

‘This is the best man in Norfolk,’ said the first one.

‘At what?’ asked Uncle Joe.

The man held up his fists. ‘Using them.’

Uncle Joe could see what was coming. ‘I’m afraid you are wrong, pal,’ he said.

‘Why?’ asked the man.

‘He was the best man in Norfolk.’

‘What do you mean, was?’

‘He’s the best man in Norfolk now – my nephew, over there. Him with the red head.’ They looked over at me.

‘Well, he has to prove it,’ said the first man.

That was music to my ears. I’d rather be a hammer than a nail, as Simon and Garfunkel sang at the time. We walked to the car park of a nearby pub, the entire site following us like children behind the Pied Piper, and squared off. I could tell he was a good man: he had a solid stance and he knew how to duck, sway and block. We fenced around for a few minutes, getting each other’s measure, and then went at it hard. He tried his best but my arms were like pistons. I punched him all around the car park.

He went down but gamely pulled himself up and came back at me. I brushed his punches aside, cracked him on the jaw and downed him again. Once more he got up, still full of fight. I moved in close, took his hooks on my arms, then sank both fists into his rib cage. The air went out of him like bellows emptying. He crumpled at my feet, grabbing me around the knees as he went down. I tried to pull my legs free but he clung on, too beaten to rise but refusing to let go. His friends came in and carried him away and I was acknowledged as the winner. We had no more trouble on that camp.

I had fights on other stopping grounds. Most I don’t even remember, but I won them all. Usually nobody wanted to mess with me: word travels very fast on the gypsy bush telegraph. Men would come up and ask who I was. ‘I’m Old Bartley Gorman,’ I would say, in homage to my grandfather.

My first encounter with one of the top gypsy fighters came not long after the Price fight. I was travelling in the south of England with a pal called Billy ‘the Box’ Vincent and we drove through the Dartford Tunnel into Kent. I saw a tan (stopping place) with vans parked about and a bit of a horse sale going on, and pulled in. There was a pub nearby that was so rough it was known as the ‘Blood Tap’. You didn’t go in there unless you wanted to fight, so I headed straight there and made it known in no uncertain manner that I was the best man in the country.

A powerful young fellow challenged me out immediately. His name was Mark Ripley and, like me, he was one of a new generation of challengers for Hughie Burton’s throne.

‘Come on then, I’ll fight you,’ I said. We went out to the car park.

‘No foreigners come here and challenge it out,’ he said. ‘I’m the best man in Kent.’ With that, he put his fist through a car headlight.

‘I’m the best man in England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales,’ I replied.

He came at me. Ripley was thickset – what we call butty – and very, very tough. We punched each other senseless. Sometimes I was very arrogant: I would go toe-to-toe just to test my opponent, throwing science out of the window. We traded blow for blow, like two bulls, virtually shoulder to shoulder. Things were just getting very interesting when it was broken up; someone said police were on the way.

We agreed to go back to the stopping ground and resume there. I had no-one with me, just Billy the Box, among a crowd of Ripley’s supporters, but I was supremely confident. We found a secluded spot among the trailers and, with a circle of people around us, went at it again. I hooked him and hurt him and put him over a car bonnet but he came back with a headbutt that caught me on the cheek. He wouldn’t go down, whatever I hit him with. The crowd also started to press in: there were women running around and pulling at me and hitting me. They were trying to interfere and he was still punching. He had no fear in him.

Finally it was stopped again. We faced each other, panting.

‘Go back up north where you come from,’ gasped Ripley.

‘I go where I want,’ I said.

Some of the older people in the crowd wouldn’t let it go on and so we both walked back to our trailers to wash off. I deliberately stopped on the site for another three days but had no more trouble, even though the old men kept coming up to me, saying, ‘Go and fetch your breed.’

‘I don’t need them,’ I replied. ‘It’s just me and your man. A fair fight.’

We never came to blows again and before I left, Ripley and I shook hands, which surprised his people. But I don’t want to stay enemies with any man. I later learned that he was everything he said he was – the best man in Kent and one of the most dangerous in the country. He was the kind who would stand on his own against 100 men rather than back down. We would never fight again but I would hear stories about him from time to time. Years later he was shot stone dead by his wife in a Kent pub called the Black Boy.

Through fights like this, and by talking to old-timers, I learned the secret skills of the bareknuckle fighter. Anyone can be a five-second pub brawler but to go for an hour and more against a fit, trained man requires what the old-timers called bottom, and an arsenal of blows that you don’t learn in the gym. For example, you don’t always punch with your knuckles. Sometimes it’s best to use your middle knuckles – the joints where your fingers bend. Some martial artists do the same, apparently. It allows you to extend your reach and to hit sensitive targets you cannot always strike effectively with your clenched fists.

My repertoire eventually included some very nasty strikes:

Middle knuckle shot between the lip and the nose – agony

Single middle knuckle in the eye socket – causes loss of vision

Punch to the bone behind the ear – potentially fatal

Simultaneous double punch behind the ears – a jawbreaker

Rabbit punch to the kidneys – wicked with bare fists

Right to the heart – another very dangerous strike

Left or right under the armpit – excruciatingly painful

Solar plexus punch – drains your opponent’s power

Hook under the floating rib – turns his lips blue

Punch to the Adam’s apple – a critical blow

Bull-hammer – end of story.

The bull-hammer was my pet name for a full-blooded right smash to the temple or forehead. I named it after the poleaxe, a sledgehammer with a spike at one end: they used to kill cows or bullocks by putting a rope through an iron ring fixed to the ground to pull their heads down, then striking them between the eyes with the poleaxe. My punch had a similar effect but it didn’t do my hand any good. I would break the knuckles four for five times over the years, whereas my left is fine – though I could hit as hard with either hand.

I picked up moves and tricks from all over the place. Tucker Dunn taught me the knuckle shot to the eye. Hughie Burton liked to put the knee between the legs, though that was never my style. I learned a good few moves from an old chap of six foot eight who had boxed Primo Carnera in an exhibition in Hanley in the Thirties. One thing I discovered myself is that attack is defence in bareknuckle fighting: your opponent can’t hit you if he is covering up. The old-time pugilists would stand strong and not take a backward step, at least until the Jewish master Daniel Mendoza came along and taught footwork and clever slipping. I like to move around and showboat – I suppose it was the Ali influence – but when things got serious I would always come down off my toes and put the other man on the defensive. They usually didn’t last long after that.

I like to break the mould. For example, who says you have to square off? When you square up to a man you automatically put him at the same level as you. If fighters have swallowed that over many years, that is up to them, but I do my own thing. Often I would just walk in with my hands low and explode, though you have to be tough to do it. I also liked to plant a big right out of the blue, without throwing the left first. You leave yourself open by doing it but, in a fight, who dares wins.

*

YOU WOULD NOT know it today, but in the Sixties Uttoxeter was teeming with American soldiers. There was a big US Army base nearby at Marchington and others in the surrounding area, for troops stationed here after Charles de Gaulle had said he wanted them off French soil. The Vietnam War was reaching its height and many of them were on their way to, or back from, the jungles of south-east Asia. When I wasn’t travelling, my main pub was the Wheatsheaf in the centre of town, and it had a television on permanently for the Americans who wanted to follow what was happening in ’Nam. They would swagger in in their military-issue cloaks and sunglasses, swishing canes with gold handles and flashing their money. ‘Hey mac, you got a sister?’ they’d say. ‘Bring her over and I’ll sell you some leather boots.’

We got on with them well – they were always willing to sell us boots and clothing and other stores that we could make a pound on – but there were also plenty who liked to fight. The pubs and dancehalls became battlegrounds most weekends and I was usually in the thick of it.

During one punch-up at a dance at the town hall, this big Yank, the bully of the camp, made a beeline for me.

‘I won’t mess about with you,’ I said. ‘If you want to fight, we will.’ I punched him once and knocked him spark out.

Word must have spread around the base about the big redheaded gypsy, because after that I was always fighting with them: blacks from Harlem, Italians like Marciano, Mid-West farmhands, Texas cowpokes, switchblade merchants from the ghettoes of Chicago and Philadelphia. Many of them boxed in the Army and some had been pros in civilian life. They loved to fight but their Military Police could be ferocious, beating them with big sticks and throwing them in the back of trucks like bags of ’taters.

I had one go with a big black, a proper pro, outside the Wheatsheaf. His name was Al, and the fight started after an English girl inside kept shouting out, ‘Al’s tough, Al’s tough.’ I decided to see how tough he was. He stripped to the waist and his torso was like black marble. We were both jabbing and hooking in an orthodox style when one of his friends flicked a cigarette at me. Somehow it went down the top of one of my Luton shoes and I felt a burning sensation in my foot. I was hopping around on one leg trying to put it out while this big boxer tried to take my head off. Finally he grabbed me in a bear hug and pinned my arms to my sides, picked me up off the floor and squeezed and squeezed with his massive arms until I could feel the breath going out of me. Somehow I managed to create enough space to tilt back my head and butted him as hard as I could right in the face. He let go and I dropped to my feet. I ducked my shoulder into his ribcage, picked him up and then shoulder-carried him for twenty yards into a wall. He slid down it like butter off a hot knife and that was the end of Al.

Somehow I always knew I could get out of any situation. Even as a child, if a big lad had me in a headlock I would stick it out no matter how long he held me, breathing slowly and waiting until his grip relaxed slightly and I could get him. I would never give up. Watching my back against the Yanks was my cousin Joe ‘Blood’ Gorman, five years older than me, about five foot eight and hard as an anvil, with a stomach like a rubbing board. Joe was so ugly he was good looking. He runs a camp now at Southport, near Liverpool, and we’re still the best of pals.

*

I DO NOT want to give the impression that all I did was fight. Far from it. This was after all, the Swinging Sixties, with the Beatles and Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones dominating the charts and Flower Power on its way. We loved music, singing and dancing. My brother Sam and some friends formed a band called the Ramblers and I bought them instruments and managed them. I wore love beads around my neck and would buy shirts and rip them up the seams at either side so you could see the rippling muscles.

I also fell in love. I met Gwendoline Wheeldon, a dark-haired lass with flashing eyes around 1967, and eventually moved out of my parents’ trailer to live with her. For the next three years, we travelled: around North Wales, Shropshire, Herefordshire and Gloucestershire, but mainly Norfolk. I creosoted miles and miles of turkey sheds, one after the other, for Bernard Matthews. I also bought and sold thousands of hessian sacks, making a penny profit on each. The farmers used them for their corn and meal but the trade eventually died with paper and plastic bags. Then I went into partnership scrap dealing, travelling down to London trading metal.

I got to know every inch of Norfolk, the area of Jem Mace. I befriended Allie Bailey, who ran Norwich then with his brothers and Big Leo McCarthy. We would meet in cafes and snooker halls, always doing deals. I also still boxed occasionally on amateur shows, under aliases. I’d just turn up at a show and say, ‘I’m a boxer, heavyweight,’ and they’d be interested. I also beat men from every major building firm in Britain. When they were laying a big pipeline through Norfolk I would go and challenge them out just for the fun of it. I remember battering one of the local toughs at a tin-hut billiard hall at Fakenham. He and his friend were looking for trouble and I was the stranger in town.

When I was twenty-four, Gwendoline said to me, ‘Bartley, I’m having a baby.’ We were stopping in Ringland Woods, near Norwich. A fortnight before she was due, she said she was ill. I made her Sunday dinner but she couldn’t eat it. I was a bit upset because I had cooked it specially for her: you know what an idiot you can be. I took her to a doctor but he said there wasn’t a problem. We didn’t know then that the baby was already dead. Little Bartholomew Gorman VI was stillborn on April 19, 1969. His tiny grave is at Cottesley in Norfolk.

Gwendoline soon became pregnant again and decided that she wanted to return home. I had not seen my own parents for three years. I had made a lot of money and if we had stayed I would be a rich man today, but we went back to Uttoxeter. My son Shaun was born in Derby Hospital in 1970 and my daughter Maria arrived in 1971.

*

WHEN I RETURNED to Uttoxeter I was twenty-six and like a Hereford bull. I went to different gyms and sparred with pro fighters who didn’t know me. All they wanted was a sparring partner. I liked the mystery of it all. We set up our own gym above the Black Swan Inn and named it the Uttoxeter Lads Boxing Club. My father helped to pay for everything: we had light and heavy bags, a speedball, skipping ropes, a rowing machine and a mirror for shadow boxing and Wogga Wood helped out with the training. Soon we had professionals like bantamweight Billy Williams over there and got a proper ring up.

Bobby Neill, the trainer I had written to several years earlier to ask about turning pro, was now running the British Boxing Board of Control gym in Highgate, north London. I got his phone number and arranged to meet him down there in a public house by the gym. I drove down in a mini-van and walked in with my kitbag over my shoulder. He was talking to some Americans.

‘Go to the gym and tell them Bobby Neill sent you and I will be over in ten minutes,’ he said. ‘Strip off and get your gear on.’

I went over to the gym. There was a leather-faced old curmudgeon on the door with spectacles and an ancient coat on.

‘You can’t come in here,’ he said. ‘Who are you?’

‘I’m the King of the Gypsies.’

‘Yeah, and I’m the Queen of England.’

‘No, I am. Bobby Neill sent me.’

He got on the phone and two minutes later let me in. I changed into my trunks and began moving around the gym, shadow boxing and warming up. Without even realising it, I took over the place. The other boxers all slowed down and were watching me out of the corners of their eyes: the big, wild-looking traveller with a mane of blood-red hair.

Bobby Neill walked in with the Americans. ‘Who do you want me to spar with?’ I asked.

Neill asked four heavyweights and none would spar with me. So he said, ‘Go on the heavy bag and I will tell you if you can make it.’

I went on the bag for three minutes. All the gym stopped and watched me. Then Neill said quietly, ‘You’re one of the heaviest punchers I have ever seen in my life. And I have seen Liston, Johansson and Cooper.’

I hadn’t even been hitting it as hard as I could: I had concentrated on accuracy, making sure I looked good. This sounded promising.

‘Yeah, you can make it,’ he said. ‘Go back and have four amateur fights and I will get you a pro licence.’

‘No, I’m not having amateur fights. I’m the champion of the gypsies, no-one can beat me right now.’

‘You have to, you can’t get a licence otherwise.’

He was adamant and, because of that, I never returned. I was in my mid-twenties by this time and had realised how good I was. I would have felt I was taking advantage by going back among amateurs. So I decided that if I couldn’t make it inside the system, I’d do it outside.

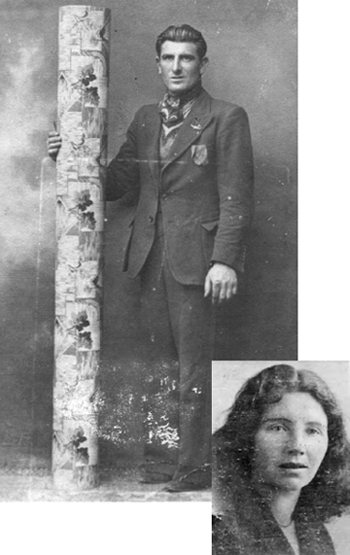

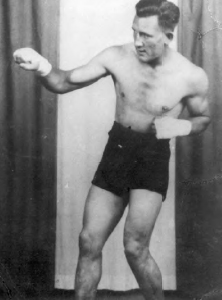

King of the Gypsies: This photograph was taken in 1974, when I was thirty years old and had just challenged the Londoner Roy ‘Pretty Boy’ Shaw to a bareknuckle fight (which never came off).

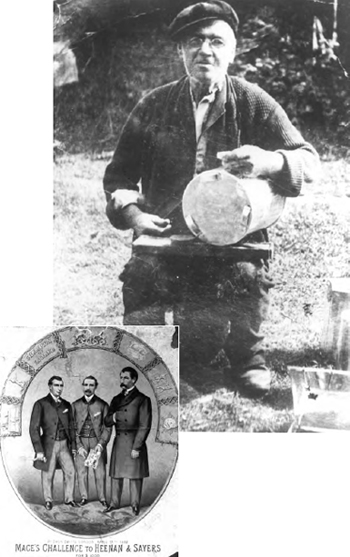

Above: My great-grandfather Bartley Gorman the First, Irish tinker and bareknuckle champion.

Left: Jem Mace, in the middle, challenging the winner of the world title fight between Tom Sayers and John C. Heenan. Mace fought my great-grandfather on the cobbles in Dublin.

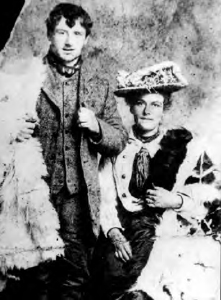

My grandfather “Bulldog” Bartley Gorman the Second with his wife Caroline, in a photograph taken around 1920. Notice his three kiss-curls.

My maternal grandparents, Jack Wilson and his wife Mary. Wilson was a very wealthy horse dealer and backed Bulldog Bartley to fight any man in the world.

How they lived: That’s my mother second from the right with members of her family. They were very proud travellers, always immaculately dressed, with the men in collars and ties. Notice the old cars and the lurcher dog.

My father Samuel made his living selling carpets and oil cloth (lino). He and my mother Kathryn ‘Katy’ Gorman, née Wilson, were married near Nottingham and had a big banquet in a field.

Mam with me (left) and Sam, outside our trailer. I was raised in a trailer (caravan) known as a ‘tank’.

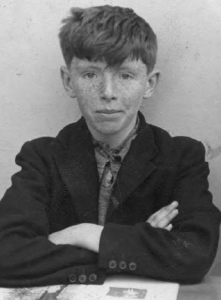

As a freckle-faced schoolboy in Bedworth. I had only a few years of schooling but did learn to read and write.

Painting barns in the hot sun: We left school to work as soon as we were old enough and painted miles of farm buildings, hay lofts and turkey sheds in East Anglia, using a long hose and a pump to spray the paint.

These two pages show some of the all-time great gypsy prize-fighters, never seen in print before. Top left is Old Bill Elliott, an unbeaten heavyweight who was the same era as my grandfather, though they never fought. Right is Riley Smith, boxer and bareknuckle man from the East Midlands and one of the top men of the 1930s.

A very rare photo of an old gypsy prize-fight: My uncle Bartley Gorman III (left) squares off against Joe Lock in Lancashire in the 1930s. Uncle Bartley was one of the best men in Wales, Cheshire and Lancashire. He won this fight.

Johnny Winters, a true fighting legend, was emulated by many travelling men in his dress and bearing.

Sam Price was a powerhouse who beat everyone he fought. He had two brutal encounters with Johnny Winters.

Benny Marshall, the master boxer from Wales who won an ABA title and became one of the best men of the 1930s.

My Uncle Ticker, booth boxer and knuckle man. He was the same height and build as me and would fight anyone.

The men take a break during a day’s work: (from left) my father, cousin Kevin Gorman, my brother Sam, old John Stevens, my Uncle Bartley, John Stevens, Clarence Gorman and me. Notice my dad glaring at me to make sure I’m standing straight.

Sam lifts up our younger brother John. You can see how strong he was, even as a teenager.

Me, aged twenty, in a field in North Wales, ready to fight anyone and determined to become the gypsy champ.