IT STARTED WITH a chance encounter on a country road. Not long after my father died, I was driving through Ashbourne in Derbyshire when I saw a tall man with a long nose, hair two feet long with grips in and teeth like dice. I could tell a travelling man if he was lying under a stone and this one was a dead giveaway: he looked like Buffalo Bill. I stopped and hailed him. His name was William Lee and it turned out he was the brother of my Uncle Pat’s wife. The Lees are one of the biggest travelling breeds and William was one of the richest of them. His business was selling carpets and he was the greatest salesmen of them you would ever meet.

He owned a herd of 500 black and white horses – he wouldn’t have a brown one – with three stallions in a field. Violet, his wife, hung in gold and jewels. He also had hundreds of English gamecocks that he paid a farmer to look after. In his caravan at night he would bring in a dozen cocks and let them fight to the death on his two-inch-thick Wilton carpet, feathers flying all over the Crown Derby and Royal Worcester. His wife would be cooking while the birds were fighting. He was clean as a new pin but he was a real sporting man. He was also the only gypsy ever to win the Waterloo Cup, the annual greyhound coursing trophy.

I got to know the Lees very well. Lord Tony Gather, who owned an estate at Ashbourne, spent six months of every year in Africa and the Lees would rent his estate while he was away. It had a caravan site, a clubhouse and acres of fields, and they held barbecues for hundreds of people. The country house had guns from the Battle of Waterloo over the fireplace.

William Lee was mad on the bareknuckle game. ‘I can’t understand, your Uncle Pat never did tell me he had nephews that could fight like you and Sam,’ he used to say. He was great friends with Hughie Burton and it was William who told me what a monster Burton was when I was going to fight him at Doncaster. After that he put up a gym for me – I could make the punchball hit the ground – and said, ‘Bartley, you are not the best fighter among travellers. You are the best fighter in England. I will put any money on you.’

We became such friends. One day he pulled up in a new Range Rover. He’d had bother with some men in Yorkshire. ‘I want you to fight someone,’ he said. ‘He’s done a very bad trick on me Bartley. Would you fight him for me?’

I jumped straight in, with our Sam for back-up in case there was a gang. We went all the way up to North Yorkshire but the man was too scared to fight me. Afterwards William said, ‘I’ll give you a horse for that.’

‘No, no, I don’t want a horse, William.’

The next day a man arrived with a cattle box with a horse in it worth £1,000. I took it because I couldn’t insult him. It was over fifteen hands, a bay mare. Lee was like that: he always wanted to buy the drink, always wanted to buy the food, he was kindness beyond all reason. But I have always said in my life that the nicest person you’ll ever meet is also the nastiest. And so it would prove.

William moved away and I didn’t see him for a while. Then one day I picked up the Daily Mirror and saw the headline, ‘Gypsy Man Robbed of £150,000.’ That was an awful lot of money in the early Seventies. It said the money belonged to a man called Jack Lee and had been taken from a caravan. I thought no more of it, as I didn’t know who Jack Lee was.

A fortnight later I was sitting with my mother in her trailer when a knock came at the door. It was four CID from the north of England.

‘Can we have a word with Bartley and Sam Gorman?’

‘I’m Bartley Gorman. What’s it about?’

‘We’ve come to interview you about the theft from Lee.’

‘What do you mean, Lee?’

‘William Lee.’

William was Jack Lee’s son and the money really belonged to him. And for some reason, they were pointing the finger at me. I hit the roof. I have never taken so much as the weight of a pin in my life, brought up by my father as a practising Catholic. I had been painting barns every day, slaving to earn a few quid, and here were these police accusing me of burglary.

‘Get out of this trailer, insulting me,’ I shouted. ‘I’ve got nothing to say to you.’

I do not know what put it into Lee’s mind. Apparently he had told the police that me, Sam and my cousin Matt Bryan had stolen the cash, which he kept in his trailer. Sam and Matt had been to visit Lee on the camp at Pontefract but he wasn’t there. His money disappeared at about the same time and that’s why they were accused. For some reason Lee had it in his head that I was involved.

The police got nowhere with it but Lee wouldn’t let it drop. He quizzed people around Uttoxeter, men who used to work for me. The CID dug up a shed where I used to keep gamecocks to see if the money was underneath. They even went to Marchington Aerodrome and searched a smashed-up motorcar that belonged to Sam. It was ridiculous.

The truth was that Lee was always flashing his money about. Decimalisation had just come in, when everyone had to change their cash into new currency, and Lee had been counting his money on the floor of his trailer when a man from London walked in without knocking. I know who he was; he was staying on the site.

‘Oh, sorry mate,’ said the Londoner.

‘Come in, it’s all right,’ said Lee, being flash. The man clocked his pile of notes and a week later, Lee was robbed. You didn’t need to be a detective to work out what had happened. Yet for some reason we were put in the frame.

I didn’t hide. I even went up to Pontefract to try to sort it out and spoke to old Jack Lee. ‘They wasn’t that clever, you know,’ he said. ‘There was another sixteen thousand under that bunk.’

I was upset by the whole thing but thought it would die down. I went over to Hinckley, in Leicestershire, where my mother lived on a site and was chatting in the trailer of Jimmy ‘the Duck’ Winters, an old-time prizefighter who walked like a duck, when suddenly he said, ‘Shaydicks.’ That means police in Cant (in Romany it’s muskras). There was a warrant out for me at the time for having no car tax and I assumed it was over that, so I said, ‘Let me get under the bed.’

Swarms of plainclothes officers came on the ground as I slid under the bunk.

‘By God, if it’s over the tax, it’s a funny do,’ said Jimmy. ‘Very strange. It’s full of CID.’ He gave me a running commentary on what was happening. ‘Your Aunt Nudi’s talking to two CID with walkie-talkies. Now she’s heading this way.’

I heard my aunt shout from outside, ‘Come out of there, my lad, hiding over the tax. It’s not tax, it’s William Lee they want you for. For robbing.’

They had come to arrest me. I walked out of the trailer and stood in the middle of the ground with 100 travellers and dozens of police around me. One stone-faced officer in a suit walked up and looked me straight in the eyes. No speaking. I couldn’t outstare him. He was an expert.

‘I’ve come to talk to you about William Lee’s robbery,’ he finally said. ‘I want to talk to you in private.’

I had a feeling this was the kind of man who could get me ten years for something I’d not done.

‘Listen. Anything you have to ask me, do it now in front of all these gypsy men here. I’ve got nothing to hide. Ask me here, now.’

‘Why, do you want a conference?’

‘Yeah, if you want.’

‘No, let’s talk in private.’

‘No, let’s talk out here.’

He wouldn’t. In the end I agreed to go in my mother’s Morecambe trailer. As I walked in, he followed me with another seven plainclothes men.

‘Hang on,’ I said, ‘if you want to talk to me, you talk to me. Get these others out.’ I pointed to a religious picture on the wall. ‘Before you go any further, that’s the Sacred Heart. On the Sacred Heart, I don’t know anything about this.’

He didn’t take a blind bit of notice. We had a long talk. He asked me questions. I told him I was innocent. He arrested me. I was taken in an unmarked car to Pontefract. The officers kept asking me about prize-fighting. They were fascinated.

‘Yeah, I prize-fight all the time, bareknuckle,’ I said.

‘Could you get us to see one, Bartley?’

‘No, sorry. Too secret.’

At Pontefract nick they gave me a drink and locked me in a cell. I couldn’t say if I was there for two days or three. CID would come in, talk to me for ten minutes, then leave. In would come another two. By the end I almost thought I had done the crime.

Finally one of them said, ‘We are sending for a man and when he comes here he’s got something to say to you.’

I thought, right, when this man comes, whoever he is, I’m going to break every bone in his body. In the event, there was no man. They had made it up. They were saying it all day long. ‘Oh, he’ll be here in a minute,’ and so on. Psychological warfare.

After a long time, in walked this giant officer, six foot five, with black curly hair. I was sitting on the bunk. He locked the door behind him.

‘So you’re the King of the Gypsies.’

‘Yeah, that’s me.’

‘Have you told any lie since you’ve been in here?’

During the questioning, one of the things I had denied was throwing a half-hundredweight rock through the window of a man I’d had a row with. I decided to come clean. ‘Yeah, I have told a lie and the lie was in saying I never put that rock through the window. I did, but only because he insulted my father and mother. That was the only lie.’

‘Before we go any further, you’re the King of the Gypsies. I’m the judo champion of Yorkshire Police. If you’ve told another lie, I’m here to tell you now you’d better go straight from this cell and get the first plane out of England.’

I have been angry in my life but never as mad as this. Born in the heart of England, Robin Hood country, never committed no crime, and now this.

‘You’re telling me to get out of England?’ I shouted. ‘My country, where I was born? Why you ...’

I didn’t punch him. I stood up, put my hands on his shoulders and crushed him down. He folded like an accordion. Even I didn’t know I had such strength. Other officers were watching through the spyhole and I could hear them outside, frantically trying to open the door. Ten CID rushed in and one put his arms around me.

‘Come on Bartley, we know you’re innocent now. Do you want a cup of tea?’

‘No, just let me go.’

I was released but it didn’t end there. The most hurtful blow of all came when William Lee rang me himself. ‘Even Will Braddock thinks you’ve had the money, Bartley,’ he said.

I couldn’t believe that. Braddock was my mentor. I loved him like a brother.

‘He doesn’t, William. He wouldn’t say that.’

Lee and his wife Violet picked me up in their Range Rover and drove Sam and me through the night to Braddock’s house near Market Drayton.

‘What’s this, Will?’ I said. ‘Are you saying this about me?’ ‘Good Lord, I never said that, like.’

‘You did say it, Will,’ said Lee. Then Violet fell down on her knees in the middle of the house, her gold jewellery jangling, and clasped her hands together and wailed, ‘It’s cold as my brother in the clay that you said it, Will.’ That was a blood oath; she had worshipped her brother, who died young. I knew that she was telling the truth. Braddock must have been after some reward. Tears came in my eyes.

‘I never thought you would do something like that to me, Will,’ I said as I walked out.

*

IN THE AUTUMN of 1976, I was barn-painting in the Derbyshire hills. It was a Friday and I finished late and drove back to Stoke-on-Trent, where I was living in a small terraced house with Gwendoline and our two children. I stopped on the way as I always did to buy Shaun and Maria some sweets.

As I came in the house, Gwendoline met me. She looked pale and drawn. ‘Bartley, your brother John’s been here. He’s been battered. Bob Gaskin came up to him at Doncaster, asked where you were and hit him. His eyebrow looks like a shark’s mouth.’

‘What? Gaskin’s hit my brother John? My baby brother? Bob Gaskin?’

‘Yes, and they’ve got a ring up there at Doncaster and they’re waiting for you to go and fight.’

I gave the children their sweets, walked back through the hallway and kicked the front door off its hinges. It was my John, whom I carried out of the hospital when he was born, carried into the world and loved like he was my own little child. I jumped in the Transit van and headed for Hinckley, where Sam lived. I went that fast that a tyre blew and the van went into a skid and nearly overturned.

Sam was in bed in his trailer. ‘Sam, Bob Gaskin has put stitches in our John’s eye and cut all his lips.’

He half-opened one eye. ‘Let me sleep, I’ll deal with him in the morning,’ he mumbled, then turned over and went back to sleep. Sam would not have cared for Jack Johnson, Joe Frazier and Mike Tyson in the ring at the same time.

I made myself a cup of tea while Sam slept. An hour later, John arrived. I couldn’t speak when I saw him. He had a long cut over his eye, a split lip and a busted nose. His face was bruised and swollen and his hair was matted with congealed blood. He was with a band of travellers led by Tucker Lee, a well-known Romany from up Darlington way. John had been living with Tucker’s family and they had gone to Doncaster for St Leger week. He had been step-dancing on a board covered with salt to the sound of a melodeon when Bob Gaskin approached with his gang of men.

‘Where’s your brother?’ demanded Gaskin.

‘He’s not here,’ said John.

‘Why isn’t he here to defend his title? He’s scared to fight me.’

‘No he’s not.’

Gaskin hit John several full-blooded punches to the face. I’m proud to say he didn’t go down but his brow was slashed open.

The men said Gaskin had put up a ring and was waiting to fight me for £10,000 a side. I didn’t have that kind of money but no matter whether it was £10,000 or ten pence, Gaskin was going to suffer for what he had done. A hired man called Danny Shenton was apparently ready to fight our Sam, and some of the others with John had brought boxing boots with them and were also expecting to fight. Tucker Lee said he could guarantee us fair play, even though it was Gaskin’s backyard. ‘We’ve got a lot of men there, Bartley, and they’ll all be waiting, ready,’ he said.

Because of his assurances, I didn’t round up any of my own breed. Instead I stayed the night at the house of my pal Frank McAleer. Frank was a proper Irishman, drinking every day. We’d be sitting in a pub and I’d say to Frank, ‘Show them what tough men is.’ Then he would eat his pint glass: chew it and swallow it without cutting his lips.

I lay in the bath all night, thinking about the man I was going to fight. Gaskin was a bad man from a fighting family. He was the champion of Yorkshire and the surrounding counties and didn’t care for man, woman or child; he didn’t care for death. He went round with a band of notorious men, all feared; perhaps the most infamous band of gypsies that ever walked the British Isles. He had beaten a lot of men but I was the champ, the redheaded king of them all, and he wanted my title. He was also best friends with William Lee, the man who had accused me of theft. Perhaps the two incidents were linked?

Very early the next morning, Sam picked me up in a hired Vauxhall Ventura and we drove to the Hinckley camp. Someone threw a twelve-bore gun and a box of cartridges in the boot.

‘Stop. I’m not going,’ I said. ‘Take them cartridges out. Out! Else I do not go, even if he has put a hundred stitches in John. No guns.’ I’m not a gun man, have never messed with them in my life. So they took them out.

My uncle Peter Smith, a scrap iron dealer, said, ‘I’ve got ten thousand pounds. I’ll back you.’ He had the money in a bag and jumped in the motor with his son Len. But it wasn’t money I was going for. My father would not have rested in his grave if I had let the man get away with it.

We made the same procession I had taken four years earlier when I went to challenge Big Just. Then the mood had been one of high spirits, even elation; now it was grim, dark. There was little talking on the way. Everyone was sombre. We had boxing boots on and were ready to fight, one after the other.

At Doncaster, Sam pulled up on a traffic island. He wore a greatcoat and was smoking a cigar. He stood on the island shadowboxing. Doncaster was a beehive of gypsies from all over the British Isles and Europe and even America – it was the flash race for the flash travellers. As the Mercedes and Rolls-Royces rolled past and saw Sam, they tooted their horns. They knew what it meant.

We drove down near the racecourse. There were dozens of buses and maybe 1,200 people there. Everybody had known from the day before that it was coming off. We got out of the cars and started walking towards the ground where the trailers were, followed by hundreds of people. Coming the other way we met Hughie Burton.

‘Bartley, my Bartley, don’t go down there,’ he said. ‘There’s too many of them. They’ll kill you.’ Hughie knew Bob Gaskin had a mob waiting. Once he wouldn’t have cared but he was too old now and the Gaskins were too much for him.

‘I’m going down there,’ I said.

Hughie tried to get me out of the way by an old toilet block to talk me out of it but I wouldn’t listen. He was older and wiser and knew how dangerous these men were but I wanted revenge. I was in a fighting trance, pacing in a circle.

‘Someone will die today,’ I said.

‘Bartley is like our Oathy,’ muttered Hughie. ‘He doesn’t fear anything.’ He was finished as a top fighter but still, what a man: big, blond hair, ponytail. He said he was with me and we started walking again. There were thousands now sitting on top of caravans: no police or house-dwellers, gorgi people, just gypsies.

A nephew of Hughie’s called Wick-Wack Burton, a notorious man who was friendly with the Gaskins, came up to him.

‘What are you here for?’ said Wick-Wack. ‘You’re too old.’

‘Are youm with us or are youm with them?’ asked Hughie. That’s how they talk.

‘I’m with them,’ said Wick-Wack.

‘You hit me then,’ said Hughie.

‘You hit me,’ said Wick-Wack.

I was moving around, waiting for Gaskin.

‘No, you hit me.’

‘No, you hit me.’

You hit me. No, you hit me. Is this schoolboys here or what? I thought. ‘Come out the way, Hughie,’ I said. ‘He said he isn’t with us. Never mind “you hit me, I hit him, you hit me first.” I’ll hit you.’

I was stripped to the waist and ready.

‘You hit me?’ said Wick-Wack. ‘Come on den, I fight you straight away.’

He took off the jacket of his green mohair suit, removed his shirt and put up his hands. ‘You title?’ he asked, meaning, is this for the title?

‘Yeah.’

It was the quickest title fight in history. As he threw a shot, I downed him with a right cross to the eye that opened a four-inch cut on his brow and put him straight into the sludge. One punch ended the fight but broke my thumb at the same time. They took him away, his mohair trousers coated in mud.

By now there were hundreds of travellers around me, fanatical. Like a fool, I had left the car behind and jumped on the back of a flatbed truck to be driven the rest of the way to the ground. I could see what looked like thousands coming from the trailers, so many that the heat was rising from them. The grandstand wasn’t far away and the Queen was in there to watch the St Leger.

When I got down to the place we were supposed to fight, Gaskin wasn’t there. The first thing I looked for was the ring. No ring. There had been one but it was smashed up in a heap somewhere. And Tucker Lee had no men at all to see fair play. We were on our own. Hmm, I thought, I know what this is going to be now: no fair fight here.

They had taken Wick-Wack Burton to the Park Royal Hotel, where Gaskin had rounded up a gang of fighting men from the North. Among the Gaskins and Deers and Harkers all drinking was a stocky man in a white pullover. He was Danny Shenton, a gorgi and the best fighter in Yorkshire. They had offered him £1,000 to fight our Sam: £500 up front and £500 when the fight was finished. There was Peter Honeyman, another notorious fighter, Big Bocker, a horrible giant of a man from Bishop Auckland, and others. Gaskin was wealthy and had paid them.

I waited down on the site for at least an hour and was getting fed up. ‘Bring the car down,’ I told Colin Lee, so he fetched it. Am I glad he did. I sat inside and put on the radio: Tie A Yellow Ribbon was playing. I’ll stay just a couple more minutes, I thought. What a fool to have waited with no men.

*

‘THEY’RE COMING,’ SOMEONE said.

I looked and could see them arriving on trucks – tip-cab Fords and TKs, big tarmaccing lorries – and they were like troops, soldiers. I jumped out of the car and stood there in blue jeans and red boxing boots, a purple handkerchief tied round my waist, my fighting colours. As they came nearer, they started to jump from the lorries and fan out, marching towards me in a line. They looked like something out of a Walt Disney cartoon: they had long necks, short necks, fat heads, long heads, fat arses like Donald Duck. That’s how I saw them and that’s how they were. I’m looking through them and they’re still coming. They were horrible. Beast men. They had iron bars and baseball bats in their hands and they were going to try to kill me. But it was too late now. This was gypsy pride at its uttermost.

I saw a crowbar on the ground, picked it up and gave it to my brother. ‘Sam, hold that and see me fair play.’

‘No,’ he said, and threw it down. Foolish. If I had known, I would have kept it myself.

‘Moment of truth,’ I bellowed as they approached. ‘I’m the King of the Gypsies. Moment of truth.’

I was like a white Zulu with chocolate stubble, red curls hanging down. ‘Where’s Bob Gaskin?’ I shouted.

Ten men shouted back.

‘I’m him.’

‘I’m him.’

‘I’m him, brother.’

The one I was certain was Gaskin, who looked the toughest, hardest of all, walked straight towards me. He was short and thickset. I didn’t even put my hands up; I was never going to take a fighting pose with these men. They weren’t going to stand around. There wasn’t going to be any fair play. They were intent, with a purpose. They were coming for blood. I walked straight at him and hit him so hard that he went up in the air and down again and landed on his head. And that was the end of him.

Hell lit up. I was suddenly fighting four or five men at once. I downed two of them but others took their places. Out came the weapons. A man in a white vest went for my brother. Sam flattened him with a single blow, then kicked him in the ribs, saying, ‘Git up, rabbit.’ Another came out of the crowd with a long iron bar and hit Sam over the temple. Then they dragged him down and piled onto him like a rugby team. Big Bocker had brown boots on him and started kicking Sam virtually to death; booting his head with no stop.

All of our party were attacked and every single one was forced to run. They put twenty stitches in Tucker Lee’s head and a dozen in my Uncle Joe’s head. Tucker’s son Tommy got away and some of the others escaped by the skin of their teeth. John Lee lost the roof of his mouth and ended up in Carlisle Hospital – to this day he doesn’t know how. Even old Hughie Burton was attacked, though not seriously.

A man hit me and I thought it was his fist. I had never been down in my entire life but I went on one knee. Christ, I thought, can that man hit. I looked up and he had the half-shaft of a car in his hand. I carry the lump to this day on the side of my head. He hit me again and I took it on my forearm, then again and again. There were at least ten on me now. I knew I must not go down.

Danny Shenton, the hired muscle, stood there in his big white jumper, waving his arms. ‘This is not my scene,’ he shouted. ‘I don’t want this.’

‘Then give us our five hundred pounds back,’ retorted one of the mob.

‘If you ask me one more time, I will ask you for the other five hundred,’ said Shenton. ‘I came for a fair fight.’

I was knocking them over like skittles when I saw Sam down. I realised I had to get to the car to get him out of there. They were hanging on to me but I was that powerful that I waded through them like Samson. My red hair marked me out: they now all knew who Bartley Gorman was and they wanted me. Wick-Wack Burton was whacking me with an iron bar. I waded twenty yards, still on my feet, dragging them along. God must have been with me.

Somehow I got to the car. I got into the Vauxhall Ventura and immediately they started smashing it to pieces. They had kettle irons and jumped onto the roof and bonnet, putting the spikes through it. Every window was broken except the front. People were screaming and crying and spewing up.

Sam struggled into the back of the car: don’t ask me how, this was every man for himself. The rest had run like greyhound dogs. I was so pleased to see him. He leaned over to me.

‘Are you all right, my brother.’

‘Yes, Sam.’

They pulled him out of the car. I had hold of the steering wheel to stop them dragging me out too. Unbeknown to me, they put Sam’s head down under the wheels, in the sludge and the dirt, holding him there for me to run over his head. Fortunately I couldn’t start the car. Next they tried to tip it over. I opened the passenger door and jammed it so they couldn’t. Some men leaned inside trying to rip me out. The car was an automatic and try as I might, I couldn’t start it. So I put my hands on top of the door and pulled it to. They iron-barred my knuckles and fingers – they won’t make a fist properly now, they click. Then they jabbed at me with bars through the other window and tried to slug me with baseball bats.

‘Stop it,’ I shouted. One man shattered the front windscreen and the glass came into my eyes. My eyes cried blood.

There came a silence. Over by the gates as you come into Doncaster, where the caravans park, are lines of dustbins. I saw a tall, bald-headed cousin of Gaskin’s go over to the bins and pick up a big Woodpecker cider bottle. He broke the bottle over a caravan tow bar and came back with the jagged glass towards the car.

‘Don’t put that bottle in me,’ I said. ‘I come for a fair fight.’

I thought he was going for my throat. I was still holding the buckled steering wheel, my eyes full of glass and blood. Then Bob Gaskin – I know it was him, no matter what they say – took the bottle and as he came at me I lifted my leg up to kick him away. I started kicking but they grabbed my leg and put the bottle in it and grated it against my shinbone. I screamed with the pain, I tell the truth, and my back arched in agony. I screamed like I had never screamed even as a child.

They were trying to cut off my leg. I don’t know what happened next, whether somebody took the bottle off him or not, but somehow I got my leg back in. Then the beating started all over again. People were starting to go now with fright.

Our Sam, who had taken a merciless hiding, jumped in a Mercedes car. The terrified driver said, ‘Get out.’

Sam just mumbled, ‘Get going.’

I was the last man left. I thought I was going to die. They continued hammering me. I took more punishment in those eight minutes than any boxer in his entire career. The blue sky was now going blood red and turning round and round and I was going giddy. I wasn’t even defending myself any more.

A dear little lad of no more than seven or eight ran in and cuddled me, a little Irish tinker. ‘Leave him, leave him,’ he said to the men. They threw him in the air like a rag doll.

I thought, the next one that hits me, I’m going unconscious. They’ll surely leave me then. So the next one that did, I slumped, pretending. I was limp but still had my arm hooked around the wheel. Blood was coming out of my mouth like a faucet. It was a lack of blood that was making me lose consciousness. You would have thought they would quit then. Not a chance. Psychos. It became worse. They put an iron bar down my mouth, broke my teeth and smashed my larynx. I was gagging on the blood.

I don’t know why the words came out, because they are not words I ever use, but I said, ‘You are hurting me too much, my brothers.’ It made no difference. They kept calling me ‘redheaded bastard’ all the time. They were pulling my hair out, flesh coming off the scalp, all my big bouncy curls. They were fighting each other to get at me.

My Uncle Peter was a tough man who looked like Rocky Marciano. He had already grabbed a giant off the top of Sam and thrown him ten yards. I saw him trying to get men away from the car. ‘Help me, Peter,’ I said.

He ran in. ‘Don’t, Bob, please don’t do that to him,’ he pleaded.

As he said it, they all stalled to look at him and I turned the key in the ignition. The engine roared into life and I did a wheel spin and took off. A hundred men later claimed they saved me but it was my Uncle Peter. They turned on him and put out every one of his teeth with iron bars. They also took his money, the whole ten grand he had brought to stake on a fair fight.

I took off in the car but couldn’t get far. The St Leger race was running and if I had gone through the barrier I’d have gone straight into the middle of the race but I only made it about 150 yards before I started to weaken from the blood pumping out of me. I saw little Frank McAleer, whose house I had stayed at the night before. ‘Hold my head up, Frank,’ I said. I was too weak even to raise my head but Frank wouldn’t come near, he was too scared. Everybody was.

A tall, dark figure lurched in front of the motor. His clothes were in shreds and he looked like a corpse dug up after a month. One eyeball was nearly out of his head. His skin was purple, a solid bruise. I had seen fighters in a mess but nothing like this.

‘Who are you?’ I murmured. It was Sam.

Then I looked down and the carpet of the car was soaked in blood from my leg. My jeans were rolled up and the blood was oozing thick like plastic. I found a piece of rag in the car and I tied it around my wound.

A giant policeman appeared. I found out later he was called Jess Maguire. He took his tunic off and clamped it on my shin and I held onto him. An ambulance went flying down towards the crowd with its flashers on and siren blaring. I heard later that they got guns out and held up the ambulance. A second ambulance was held up, so the third wouldn’t go down. Policemen appeared everywhere with dogs. Hughie Burton came, picked me up and put me on a stretcher held by two policemen. Through the mist of my mind I could see the Gaskins standing there like grotesque cartoon characters.

I will never know how I did this, but I rolled off the stretcher, threw back my shoulders and shouted, ‘Come on, one of youse now, one man.’

Not one stepped forward.

‘Bartley Gorman, King of the Gypsies,’ I bellowed. ‘King of the Gypsies.’

Then I fell back onto the stretcher and they carried me to the ambulance.

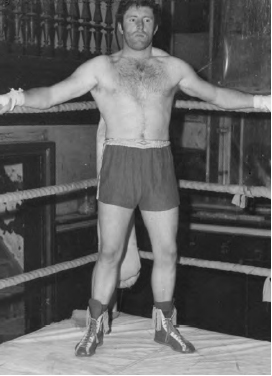

Training in my fighting prime in the Seventies. I used the boxing ring to prepare for bareknuckle fights.

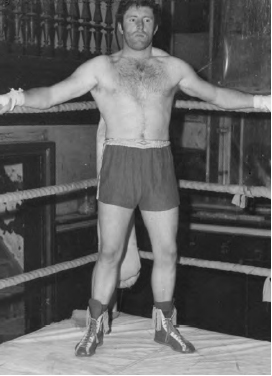

Sam knocking out ‘Alanzer Jansen’ on one of my pirate boxing shows. Even I had to get on my bike when sparring with Sam.

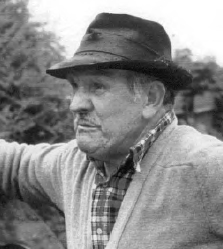

Top fighting men of the Fifties and Sixties. Left is Sam Ward and above is Jim Crow, both from the north-east and both unbeaten. Ward punched so hard he could break a bone wherever he landed.

My uncle ‘Fighting’ Peter Smith, who helped save my life at Doncaster but was badly beaten and had £10,000 stolen.

Albert ‘Nigger’ Smith, a boxing champion and rugged bareknuckle man of the Sixties and Seventies from the east coast of England.

Big Jim Nielson, the 17-stone champion, with his wife. He lost to Uriah Burton at St Boswell’s Fair when Burton bit his tit off.

Caley ‘Big Chuck’ Botton and my cousin Kathleen in Las Vegas. Caley was champion of Canada and a top man in the Burton era.

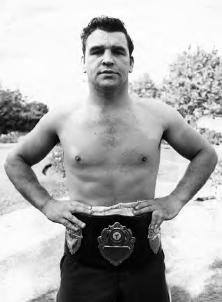

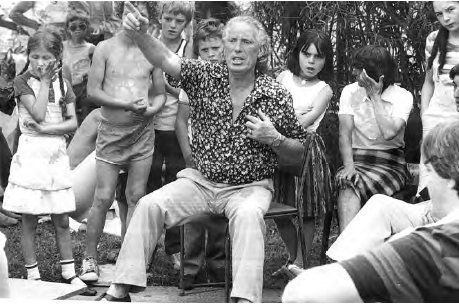

The one and only ‘Big Just’, Uriah Burton, holding an open-air court on his site near Manchester. He reigned as King of the Gypsies before me and was a brutal all-in fighter who would stop at nothing to win. He was also a man of iron principles.

Bob Braddock and (inset) his brother Will. They were my biggest backers and also two of the greatest horse dealers you could ever meet. They arranged my fight for the title against Jack Fletcher in Hollington Quarry in Staffordshire in 1972.

A historic gathering in the Blackie Boy pub in Darlington to raise money to back me against Hughie Burton. From left: Henry Nicholson, Black Wiggy Lee, Tucker Lee, Wally Francis, Jimmy Francis, Terence Lee, Chucky Francis and two men who wish to remain anonymous.

Two of my close friends and sparring partners: Siddy Smith from Leicestershire (left), posing beneath boxer Tony Sibson’s Lonsdale Belt, and Tommy ‘Tucker’ Lee, who was always one of my biggest supporters when I was fighting.

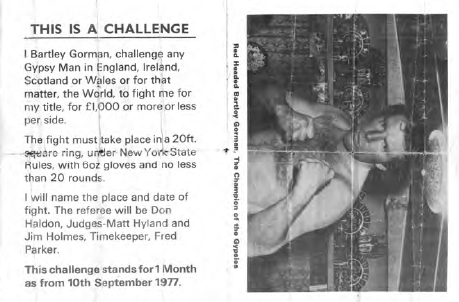

The challenge: These leaflets were distributed at Doncaster racecourse in 1977 to show that I was still the heavyweight champion of the gypsy world.

Boxing days: One of my unlicensed tournaments, with (left) MC Johnny Austin, Rabbi Boswell (who tried to persuade me to give up promoting) and ‘Blond Bomber’ Don Halden, the hard-hitting heavyweight boxer I fought outside a pub.

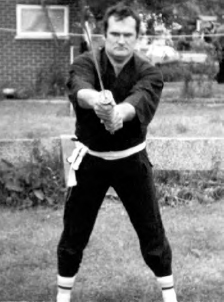

Martial arts expert Robert Shaw, wielding a ceremonial sword. He caused me to fight him on my land at Uttoxeter.

John-John Stanley (top) and Boxer Tom, two great fighters from the south whose contest in 1972 was one of the longest of modern times.

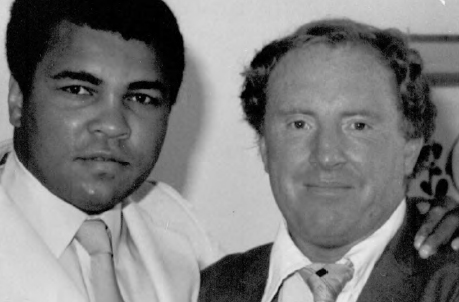

Two Kings: My meeting with ‘The Greatest’, Muhammad Ali, in Birmingham in 1983. He told me he had been champion of the world three times. I told him I was the Lord of the Lanes.

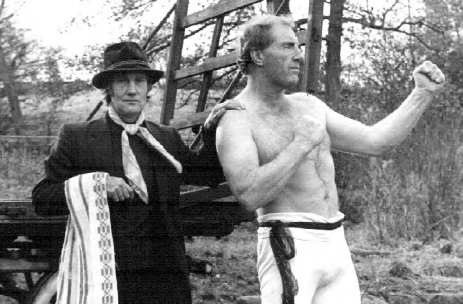

With my trainer Alan Wilson in the mid-Eighties. I loved tradition and am seen here wearing tights and an old-fashioned silk around my waist. Alan, a lovely man, was later murdered.

Chief Inspector John Kendrick is about to arrest me in a Staffordshire car park, where a huge crowd had come to see me fight Johnny Mellor in 1986. We were bound over to keep the peace.