IN THE SUMMER of 1990, the Irish travelling community was alive with talk of the biggest fight for years. Dan Rooney and Ernie McGinley had agreed to meet for the bareknuckle championship of All-Ireland at Crossmaglen, on the border between North and South, the region they call Bandit Country. They made quite a contrast. Ernie (whose real name is Denis) was a stocky bulldog of a fighter with cropped hair and a stubbly goatee. Dan was a giant, tall, heavy and handsome, with thick black hair. Both were top fighting men, brave, hard and experienced and more than ten years younger than me. I had met a couple of McGinleys before and was quite friendly with them. I also got on well with the Rooneys, though we’d had the odd fall out. It was Dan’s uncle, Felix Rooney, who had been attacked by the mob on that terrible night in Moss Side nearly twenty years earlier (see Chapter Eight), and one or two of the family still blamed me for it.

Big Dan was one of a large number of brothers and was said to be the champion of his breed. He had first claimed the Irish title after beating the ferocious Joe Joyce, who was known as ‘The Hulk’ and who had been the top man in Ireland in the Eighties. I had been due to fight The Hulk once and went to Liverpool with my cousin John to catch the ferry to Ireland but the fight was cancelled. Joyce later told everybody I fought him but I never did. His contest with Dan was brutal. Joe apparently had Dan over but Dan got up and knocked Joe down. Joe broke his ankle as he fell and couldn’t continue.

Dan and I had never got to it but I had fought his brother – another Felix – in the Eighties. A large number of Irishmen had been staying around Uttoxeter and, as usual, we had all gone drinking. Felix was one of the group and made some remark that I had left his uncle to get a beating that night in Manchester.

‘I don’t leave any man, friend,’ I said. ‘Let me tell you the story.’

I told him what had happened and it was dropped. We ended up at Peter Sellars’s house – the place I had fought the Staffordshire Wolfman – enjoying ourselves, with music on, but Felix started again. I was sick of it.

‘Do you know who I am?’ I asked him.

‘I don’t care who you are,’ he said.

‘I’m Bartley Gorman, the king of every gypsy man.’

‘I don’t care for Jack Johnson, never mind you.’

There was uproar, with people holding each other back and tables and chairs and best china going over. I didn’t want to fight Felix because I was a guest in Peter’s house and also I didn’t want to fall out with all the Irishmen, many of whom were my friends. It causes bad blood.

‘I’m going for a drink,’ I said, and left in my blue Transit van. As I pulled away, Paddy Doran, my best drinking partner, jumped in and for some reason sat on the dashboard. I was flying along, drunk, looked in the mirror and saw twenty cars chasing me: Volvos and Transits with beds, baths and antiques on top. The Irish thought I had taken Paddy to beat him up. They didn’t know we were best friends.

Eventually I pulled up in the middle of Cheadle, thinking, this is no good, I will have to fight him. The convoy screeched to a halt and blocked off the road. I jumped out and stripped off and so did Felix and we went straight at it among rows of empty market stalls. I jabbed him and he flew back straight into a wall, but he came back at me shouting, ‘I don’t value anybody.’

We started punching, really fighting, with the Irish all round us yelling and pushing each other back to make room for us. Five minutes in, I’m boxing and playing with him and he’s flustered and going mad trying to punch me. Froth was coming out of his mouth. The more he did it, the more I was taunting him. I didn’t realise we were next to the police station. They must have called for reinforcements because suddenly ten officers came running with batons drawn. They broke up the fight and told us to get in our motors and go. I went to Will Braddock’s and said, ‘Felix Rooney wants to fight me for as much as I want.’ That night we went looking for him but in the end it was called off. There’d have been too much bother over it.

Because of all this, Dan Rooney had it in his mind to fight me. A pal of mine, Alec Goram, was in a pub in Soho, London, with some Irish travellers when this black-haired giant came in.

‘Where are you from?’ he asked Alec.

‘I’m with the lads,’ said Alec.

‘Where are you from originally?’

‘Uttoxeter.’

‘You’ll be a mate of that Gorman’s then?’

‘Yes.’

‘A mate of Gorman’s isn’t a mate of mine. Do you know who I am?’

‘No, and I couldn’t care less,’ said Alec.

‘I’m Danny Rooney.’

‘So what?’

Dan picked up Alec by his collar and threw him over the bar.

I had more immediate concerns. That summer my mother died, at the age of seventy-nine. For many years she had lived at the Aston Firs site in Leicestershire, on the same plot as her brother Joe, and we took her body back there for the vigil. They buried her in blue because she was a child of Mary. I remember kissing her in the coffin and a tear fell out of my eye onto the shroud and left two little stains. I couldn’t leave my mam’s coffin; I even jumped in the hearse with her. There were eight Rolls-Royces in the funeral cortege through Hinckley, with truckloads of flowers. Her niece Maria Wilson sang a beautiful solo at the funeral. It broke my heart.

Afterwards, my brother Sam went into training to fight the winner of McGinley and Rooney. ‘I’m going to show these men what a real fighter is,’ he said. He declared he would take them on one after the other, and he would have. It is hard to describe what a powerhouse Sam was: a heavyweight Roberto Duran. He had his own gym and trained a lot of men there but never had many knuckle fights because nobody would face him. People looked at him in awe because they knew he wasn’t some built-up bodybuilder; his size and strength were natural. I was definition but our Sam was mass. He had a weights bench specially made because his arms were so long that he couldn’t use a conventional one.

He was a great boxing fan and was in Leicester for one show when Frank Bruno baulked his way at the side of the ring. ‘I didn’t know whether to blast him out of the way or not,’ said Sam; he said it so simple, as if Bruno was just anyone. I used to point to Sam and say to men, ‘See that man there? I can beat him with one hand behind my back. If you can beat him first, I will fight you.’ Sam would be scowling at me. Yet he was not at all a violent man. He loved his music and even cut a demo disc in a studio in Derby with his friend Rockin’ Johnny Austin (now an MBE for his charity work) under the name ‘the Rocksam Duo’.

The Rooney–McGinley fight went ahead in August 1990. Hundreds of travellers descended on Crossmaglen, taking over the town like an occupying army. There were kids perched on roofs and standing on walls. The atmosphere dripped with tension and there were scuffles between members of rival factions even before the two men faced off. Both were confident and no-one seemed to care at all about the garda: they fought right in the open in mid-afternoon. It was also one of the first fights ever to be filmed on video. The two men were called together in the midst of the throng and shook hands: McGinley in a red vest with his hands taped, Dan bare-chested and bare-fisted. They got right down to it, no messing about.

They swapped blows. The bobbing, weaving McGinley had trouble getting past Dan’s huge fists and long reach but he was game as a pebble and kept at it. The contrasting styles made for a ferocious fight. Unfortunately the crowd were completely unruly, despite the best efforts of the marshals, and gradually closed in around them. After several minutes it became a real toe-to-toe affair but both men were rapidly swamped by the crowd. Suddenly there was a roar. Hands were raised aloft and after several seconds of utter confusion both men were lifted onto their respective supporters’ shoulders. McGinley quickly left the area, saying he would fight Rooney again for £100,000 on Ballinasloe Green at the October fair, while the bemused crowd tried to figure out what had happened. Both had taken punishment – Ernie’s face was busted up while Dan had cuts and a black eye – and both claimed victory.

After it was over, a cousin of mine, Peter Maguire, told a reporter on the Irish Press that Bartley Gorman could beat both families one after the other. I didn’t know he was doing it and to this day I don’t know why he said it. Anyway, the paper published the story and my phone number. The first I knew was when my cousin Bessie in Liverpool rang me in a flap. ‘Bartley, my Bartley, you are going to get murdered. Why ever have you put that in the paper?’

She told me the story and posted me the cutting from the newspaper. I had a telephone in my mobile home at Fort Woodfield and soon it was ringing off the hook. Every day when I got back there were messages. ‘I’m going to bury you, you big, redheaded tramp, and I’m going to beat your brother too,’ was one, I believe from McGinley himself. A man called Jake Whaler, a good fighter in Ireland, also said he would fight me. Another time there was a call from a pub. I could hear noises in the background and a lot of Irish voices. Then someone said, ‘Go on, say it, say it.’ This gruff voice came on. ‘Now, Bartholomew Gorman. If you are as good as you think you are, tell me this ... who is going to win the three-thirty at Galway Races?’ Then laughter and they hung up. I ignored the calls. Sam was going to fight them and that would have been the end of the matter. Neither of them could have beaten our Sam.

But something was wrong with my brother, tragically wrong. I was with Peter Sellars one day when Sam came to see him over a bit of business. When he left, Peter and I turned and looked at each other in shock. Sam was a shadow of himself. He had lost weight and his face was sunken. Peter’s wife had died of cancer four years before, and he knew even then that Sam might have it too.

A short while afterwards, he went to hospital for an examination on his throat, which had been giving him a lot of trouble. I went with him and afterwards asked the doctor what he thought it was.

‘Oh, it’s only a small ulcer,’ he said.

I walked into the room where Sam was. ‘I can’t understand all this mither,’ I said. ‘It’s only a small ulcer.’

‘You’re kidding!’ He was so pleased.

That is what the man had told me. A bit later, when the test results came through, I had a phone call from my Aunt Nudi. ‘Now, he’s not very well, my lad.’ She talked round and round but never came to the point. In the end she just said, ‘Will you ring Doctor Sharkey up?’

I did. ‘It’s a small cancer,’ he said.

I went into a panic. ‘Doctor, what would you do if it was your brother?’

‘If it was my brother, I would operate.’

They had found a shadow. The doctor said to me later, ‘If Sam Gorman has got a shadow, then that is some shadow.’ He also told me there were 200 ‘species’ of cancer, as though it was an alien thing that invades someone’s body. I put the phone down and fell on the floor, clutching two pillows to my chest and rocking like a baby. ‘My brother Sam, my brother Sam,’ was all I could say. I knew it was the end of him.

Sam had cancer of the oesophagus but still didn’t know it himself. We couldn’t tell him because of his nature: he had four children – Relda, Bridie, Sam and Jerry – and was mental over them, a real family man. It would have broken him up to think he was dying. I discussed it with the doctor and we decided not to tell him.

I went to see the doctor with Sam and his wife. This was an awkward situation, because I had asked the doctor to lie. I sat with the doctor, facing Sam and Relda across the table, and everything the doctor said, they looked at me for confirmation. I was trying not to be emotional but it was hard, acting. ‘It is only a small operation,’ said the doctor. ‘We have to bypass something.’ In fact they were taking out part of his stomach and making a new one.

Sam came to my place and stayed. It was a bad time. My mother’s brother, Joe Wilson, died that August. He was a holy man who fasted and lived like a monk and sometimes used to train me. ‘The man that thinks he can beat this man must be a fool,’ he would say. John Taylor carried a fifteen-foot cross into the cemetery and there was a huge wreath made of Welsh leaves to mark his love for that country.

John Fury, my cousin’s son, came to Fort Woodfield for a visit. He was ranked the fifth best heavyweight boxer in Britain and was in training to fight fourth-ranked Henry Akinwande in an eliminator for a shot at the British heavyweight title. He would have been the man for either McGinley or Rooney but was concentrating on his boxing career. I trained with him and his brother Peter, running five miles in the morning, sparring and punching the heavy bag hanging in my field. John asked me to come to his eliminator in Manchester. I didn’t want to leave my sick brother but Sam insisted that I go. ‘Cheer him on well,’ he said. I was sure John was going to win but he was counted out in round three. It was certainly no disgrace. Akinwande, who is 6ft 7in, went on to win a world title.

Sam had his operation soon after. I went into a little chapel and prayed for the four hours he was under the knife. I made sure I was back at the operating theatre when they wheeled him out. I grabbed his hand and said, ‘All right, Sam?’

‘Oh, my brother,’ he said.

We thought he would have five years but he didn’t live six months. After the operation, he used to bring his own caravan up to Fort Woodfield and stay at mine for days. He went down to nothing. It was like he had melted. I remember him getting up and saying, ‘Holy Mother of God, Holy Mother of God. I know what’s the matter with me.’ He looked like he had had a revelation.

‘What’s the matter with you, Sam?’ his wife said.

‘It’s cancer. I’ve got cancer.’

‘Don’t be silly.’

He knew then, even though we hadn’t told him.

I even had to fight while Sam was dying. A man with a big black moustache came on our ground – I don’t think he was a traveller but he knew travelling men – looking for a fight and Sam got upset, so I just went out and steamrollered him. I don’t know who he was and I don’t want to know.

Sam thought he was getting better. He refused all morphine or painkillers and wouldn’t go into the hospital again, though the doctors begged him to. One day he got out of his bed, got dressed, and set off walking as fast as he could down country lanes to try to get life. I was with him day and night. Every morning we would play all his favourite Sixties songs on his cassette. He must have worn out the tape of I Love You More Than I Can Say. Towards the end, he declined so much that he never went out. No one saw him for weeks. Then a young man, his pal, died on the camp at Hinckley. When they told him, Sam ordered a wreath and emerged on the day of the lad’s funeral, when the ground was black with gypsies. He came out of the trailer with the flowers in his hand, though he hated anyone seeing him so weak, and walked like an old man to the lad’s trailer, with all eyes on him. He laid the wreath then slowly walked back to his own trailer and closed the door. That took some doing; he must have had some love in him.

A few weeks later he was lying in a bed in his trailer. ‘You was always better than me,’ I said to him. ‘You was the champ, Sam.’ I kissed him and they were the last words I said to him. He was looking up through the window. His son Jerry came in and I went into another room to fetch something. When I came back, little Jerry, five years old, was lying across his dad with his arms around him and Sam was dead.

Ben Smith, a travelling man from Leicester, came in at that moment. He saw what had happened, sighed and took off his cap. ‘You didn’t deserve this Sam, you didn’t,’ he said.

It was December 3, 1991. Sam was forty-six. My mother, brother and Uncle Joe had all died within a few yards of each other on the same site at Hinckley and all within eighteen months, as though a gust of wind took them off the face of the earth. I still feel Sam’s presence all the time. When I laugh at some remark I feel that Sam is smiling with me.

*

THE NEWS OF my brother’s death spread within hours. Many people didn’t believe it: to them Sam Gorman was indestructible. Visitors began to arrive to pay their respects. Messages of condolence came from all over the world.

For a week after he died I sat up with him every night. Then they laid out his body in a chapel of rest and had this piped death music in the background. I asked them to turn it off. I was devastated. I remembered when he had had fights as a young man and I was always the one to butt in. They had never closed his eyes and they were looking up. In the hollow was a great big tear and I knew it was for me. I went back that night and cried so much in the trailer that I thought my heart was going to give in.

Ernie Bryan, my dad’s cousin, came on the camp on the funeral morning. It was a cold, foggy day. Ernie looked at his sons and then saw me washing in a bowl outside the trailer. I must have looked grim. ‘I know my breed,’ said Ernie. ‘There is going to be trouble today.’ I was so distraught that I paid him no heed. I went into the trailer and put on Sam’s beautiful double-breasted suit that he had given me before he died.

Travellers came from everywhere for the funeral; some of the toughest men in England, along with newspaper reporters and television cameras. Someone counted 180 cars in the cortege. They put a photograph over the coffin of Sam squaring up in a boxing pose, while the Lees from the north of England sent a boxing glove in flowers, six feet in diameter, with ‘No 1’ on it. I bought a pair of six-ounce red boxing gloves, made in California. As they lowered Sam into the ground, I threw the gloves onto his coffin. ‘Here you are, Sam. They are not fit to lace your gloves, so let God lace them up for you,’ I said.

Big John Fury came up to me at the graveside. ‘I know I can never take your brother’s place, Bartley, but I’m always here if you need me.’ That meant a lot to me.

The tea afterwards was at a club called The Squires. We walked in and they had Christmas decorations up, baubles and gold tinsel. It was inappropriate for a funeral, glittering everywhere like some gaudy nightmare but I seemed to be the only person that noticed. Someone put the television on. I had been talking to BBC Midlands Today in the graveyard and when I saw myself, I looked ill, as though I was in a trance.

Two of Dan Rooney’s brothers were there, John and Ned, both fighting men. John was in a tee-shirt. Everyone else was in suits. There were Dorans, Wards, Taylors, Dunns, Willetts, Finneys, Wilsons, Nunns, Kidds, Egertons and many others. Eventually the tea was eaten, the women had left and just the hard-drinking men remained. Some of us moved up to another room and sat around a table with my friend Paddy Doran. Ned Rooney looked at me across the table and that was when it began.

‘It was a bad thing what you put in the Irish Press, Bartley, that you could beat every Rooney and McGinley one after the other.’

‘I never said that, Ned. I would never say that about any breeds. I’d be out of order if I said that.’

‘Well, it’s very strange. You’ve been in every paper in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales and even abroad. You’re continually in the Press. I’m asking you a question now. Do you admit you are continually in the Press?’

‘Yes.’

‘And yet this is the only time that you’ve never spoken to them?’

‘I told you, I never said it.’

‘I believe you did.’

‘Take it as read, then.’ I didn’t care what he thought about it.

Everyone had gone silent. There was a table between us and John Rooney was sitting to Ned’s right. I had no blood relation with me, and that is an important thing with travellers. The Furys and others had gone.

‘Ernie McGinley would be the man for you,’ said Ned.

I don’t usually badmouth any man but by now I was angry. ‘I could knock him out,’ I said.

‘No way could you knock him out.’

‘Well, that’s fighting, that’s the name of the game.’ You have your opinion, I have mine.

I left the table but this played on my mind. I walked back. ‘Why don’t you think I could knock him out, Ned?’

‘That’s easy to tell you. My brother Dan is the best man in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales and he couldn’t knock him out, so how can you?’

‘Hang on. Your brother Dan isn’t, because my cousin John Fury is the best man among travellers.’ I didn’t brag myself up. I was forty-six now: it was down to younger men to fight it out if they wanted to. But I wasn’t going to take much of this.

‘No way is he,’ said Ned.

‘I’m telling you that John Fury is.’

‘No way. He could never beat Dan.’

This could have gone on forever. So I said, ‘Hang on. I can knock Dan out.’

I knew that would go down like a bomb but I hadn’t expected what happened next. As we had been talking, John Rooney had risen to his feet out of my vision. Without warning, he hit me square on the left side of the mouth. He had a fist like a mallet and was wearing a four-ounce saddle ring. I should have gone over the chair backwards, but though I didn’t see the punch coming, I am always ready. As I took the blow, my right leg slammed down to brace me, and I kept my balance. I rose very slowly from my seat.

‘You are in very serious trouble now, Paddy,’ I said. ‘Get your shirt off.’

Everybody was stunned. Two top fighters were about to go at it. I was wearing my dead brother’s suit and I took off the coat and put it on the bar, then removed my tie, shirt and rosary beads. When I turned around, John had his shirt off. He always claimed to be a better man than Dan and was in the prime of his life, about twenty-eight. I’d had a lot to drink but so had everyone. The club bouncers made no attempt to interfere: they were looking forward to it as much as the others.

I was warming up, moving my body, but as I went towards him, he stopped me.

‘Hang on, is this for the title?’

‘Yes.’

A human ring formed. We came together, with the head doorman saying he wanted a nice clean fight and all that. I told Rooney, ‘I’m just about to teach you a lesson,’ and I slapped him hard up the side of the face.

‘Let’s show how two real men fight,’ I said, and pawed him with my left. I was messing about really. He was looking for his range and I pulled him in close with my hand behind his neck, shoulder to shoulder. Every Irishman was shouting, ‘Kill him, John.’ He had his blood relations and I had none; even my brother John had gone, and this would be the first time Paddy Doran had never shouted for me in a fight, though I could understand it. Still, I wasn’t taking things very seriously until Rooney sent in a fierce shot which burst my eye. He still had on his £5,000 red gold ring, set with diamonds. I never wear a ring or a watch.

‘Oh, you want it for real now?’ I said.

That was when I started to fight. As he rushed in very square with a wide guard and his body exposed, I opened up on him with body shots; I can’t remember hitting him to the head once. I was fighting a cross between George Foreman and Ken Norton, not swaying and slipping and using his own energy against him like I used to but fighting flat-footed with a cross-arm defence. I wouldn’t let him see my eyes so he didn’t know what I was going to do. He caught me with some good right hands because I was a bit drunk but his punches just bounced off me. I backed him up and he hit me a good left hook.

We had a vicious exchange, I hooked off the jab and he stumbled. The bouncer referee wanted to count but Rooney’s friends stopped him and pushed their man straight back at me. I unloaded on him. They were causing the man to take tremendous punishment. He set into me again rushing like a raging bull: head down, ready for anything. He had some bottle. There was now nothing but blood, sweat and snot. I didn’t realise at the time but I was taking some terrible head shots with this ring and all one side of my face was going black.

John Taylor moved between us. He was Sam’s wife’s brother, the best fighting brother of the Taylors. He said, ‘Take that ring off. You don’t have title fights wearing rings.’

Before anyone could answer him, I said, ‘Leave it on. Give him a chance, he’s fighting Bartley Gorman.’

I was sobering up. In the middle of the room was a decorative wooden pillar with a shelf around it to hold drinks. I put him straight through the pillar and it collapsed: drinks, glasses and all. Rooney pulled the mess off him and raised his arms aloft. ‘I’m the King of Ireland!’ he roared. Then he charged again. I waited, not budging. There was such a wicked exchange this time that I thought Rooney had broken my jaw. I punched him to the body so hard I could feel his ribs giving in.

This had gone on twenty minutes without pause. When we got in close he was calling me a ‘w* * * * r’ and I was calling him a ‘tramp’. We continued this throughout the fight.

I kept up a running commentary:

– ‘Well, at least you can always say you fought for the title.’

– ‘Do you know you are fighting the best man in England, Wales and Scotland?’

– ‘Don’t worry about losing, because you are making history.’

Paddy Doran got mixed up once and shouted, ‘Go on Bartley!’

Rooney stumbled over and young Andrew Taylor shouted, ‘Kick him in the head.’

‘No, I’ve never kicked a man in my life.’

Rooney had been badly hurt but this was some fighter, feared throughout the country. He generally only has to hit a man once. He got up and this time I felled him properly. Someone else shouted, ‘Kick him,’ and again I said no. I bent over him, going down on one knee and picked him up with one hand to hit him with the other and he said, ‘No more, Bartley, no more.’

I was always a man for the count but on this occasion no-one counted. At that moment the police burst in. They had blocked off the whole of Hinckley. Then Rooney, still game even though I’d won, said, ‘I want to finish this fight now.’ I said to the superintendent, ‘Listen, this is going to go, either in Coventry or somewhere else. Can I fight this man now and finish it?’

‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘Get it finished.’

It was impossible because of the crowd milling around. I was talking to somebody when Rooney suddenly came and hit me. I went to get back at him and more came between us, so I walked away from him to the bar and said, ‘Give me a half of lemonade.’ I thought, he has hit me after the fight has finished, on the day I buried my brother. I saw him standing by the wall with a load of men, walked through the crowd and this time I hit him so that hard to the head it bounced his skull off the wall. How that man took that punch I will never know.

This is gypsy fighting; it doesn’t finish nice and clean. I walked away. The landlord wanted us out and the police were ushering everyone outside but before we left the club, Ned Rooney, who had caused it, said, ‘Will you fight my brother again tomorrow and I will fight the next man?’

So I pointed to a friend of mine and said, ‘He’ll fight you.’

Ned stormed over to him. ‘Will you, will you fight me?’

This man said, ‘No, no I won’t.’ I won’t shame him by naming him but I was disappointed.

So I shouted up then, ‘Fetch who you want. I will have my cousin Big John Fury with me, his brother Hughie, his brother Peter and my cousins Michael, Craig and Russell.’ This caused near-panic.

The police got us into the street among the cars. There were scores of men and it was agreed we would fight again the next day. I was just sorting this out when Rooney walked through the crowd and hit me again. So I went after him and hit him so hard I broke two of his ribs. I heard later he had to go to Grantham Hospital. Despite this, we weren’t arrested. The head policeman said, ‘You have never disturbed the public, so that is fair enough with me.’

I went into a pub with Paddy Ward while they escorted the rest off to Coventry. I looked down and somehow I was wearing John Rooney’s tee-shirt. I must have put it on in all the confusion. I went mad and ripped it to pieces. ‘Tomorrow it won’t be the day I buried my brother, and I shall demolish him off the face of the earth,’ I said.

‘Tomorrow, Bartley, I’m with the boys,’ said Paddy Ward. ‘You better get that into your head.’

‘That’s good, because he is going to need you real bad,’ I replied. I believe in tact but when you are messing in the jungle, if you can’t stand it, get out.

I got on the phone to my friends up in Darlington and they were all coming down, while John Fury and his family were going to fly from Manchester to Coventry Airport.

Meanwhile John Rooney had gone to my brother John’s in Coventry. They were best friends. Rooney is one of the best uilleann pipe players in Ireland, our John plays the melodeon and that is how they know each other. There they saw another prize-fight between Paddy Doran and my cousin Ginger Stretton. They fought for half an hour before calling it a draw; too much blood had been shed that day.

That night wiser heads eventually prevailed. John Rooney came on the phone to me and we called the truce, otherwise there would have been full-scale war. He later told my brother, ‘Bartley would eat McGinley and spew him up again.’

Next day the Leicester Mercury reported:

Bare knuckle boxers sparked off a police alert when they squared up to one another at a wake for gypsy Mr Sam Gorman yesterday.

Hinckley Police called in reinforcements from Coalville and Nuneaton and sent a dozen officers to Squires nightclub, Hinckley, when an outbreak of fighting was reported at about 7pm.

About 200 people went to the club after the requiem mass of Mr Gorman, a former boxer who died last Tuesday.

Police reported that about 30 were involved in the fighting incident, but Squires owner Mr Neil Kyle said it was nothing more than a confrontation between two bare-knuckle fighters who had a long-standing feud, although there were perhaps 30 people in the room.

If you are ever in the Grapes public house at Appleby in Cumbria, you will see a wood carving of me fighting Rooney. The carving has a curse on it, by Old Haggard Aggie. They’ll tell you all about it in the pub. People come from all over to see it, not just gypsies. I met John again some years later and we shook hands. Then in December 2001, when I was very ill, he and his brother Dan both came to see me. I realised what giants they were: formidable men but nice men too.

I thought I would make that my last defence. I no longer looked for fights. The sudden deaths of my mother, brother and uncle had put me out of the frame of mind and, besides, I had nothing to prove. But I could not seem to live a quiet life.

With my children Maria and Shaun. We never actually lived in a wooden trailer like this but it made for a nice photograph!

Marcko ‘Hangallis’ Small, the gypsy ringmaster (referee) who was behind plans for me to fight the American Jade Johson.

Joe-Boy Botton, from Hemel Hempstead, who once told me he would fight any other 50-year-old in England for £10,000.

With my girlfriend Ann Shenton at the funeral of antiques dealer Les Oakes. The man with his arm around Ann is Billy the Black, who I once fought, and on the right is Malcolm Barrett, an old friend and very successful businessman.

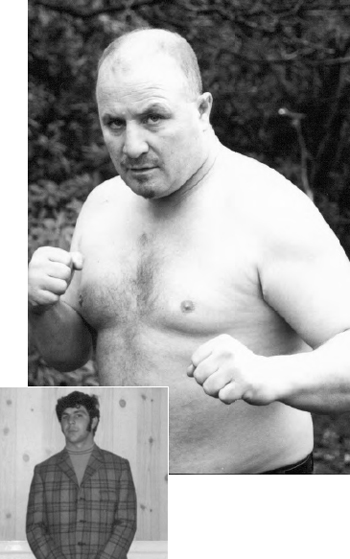

Two of the most feared gypsy fighters of the past thirty years. Henry Francis (above) is as deadly with his head as he is with his fists. Our brawl in a car park in Nottinghamshire was stopped by the police.

Henry Arab (left), from the north-east of England, has knocked out so many teeth he is known as the ‘Dental Surgeon’.

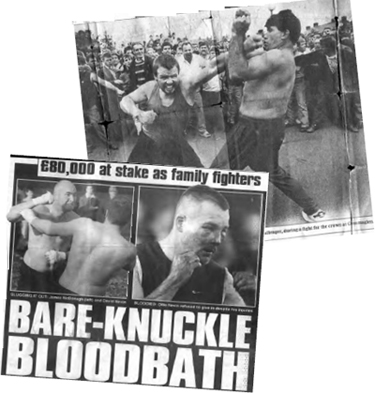

Newspaper reports of the Irish fighting scene.

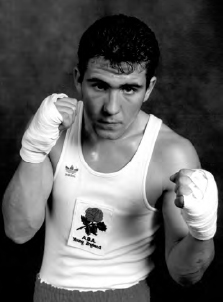

Left, the mighty Joe ‘the Hulk’ Joyce, a real rough-and-tumble brawler.

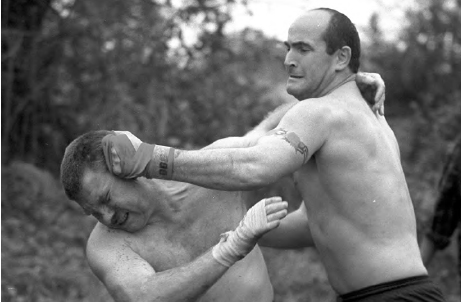

Right, the famous contest between Ernie McGinley (left) and Dan Rooney at Crossmaglen in 1990.

Left, coverage of a series of fights between the Nevin and McDonagh families. The irish are more open about knuckle fights and many are now filmed on video.

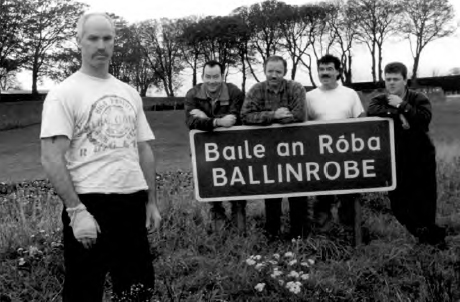

Bernie Ward (left) and friends in a field in Ireland. Bernie was called the ‘King of the Travellers’ in a court case, though he denied it.

Jimmy Quinn-McDonagh beating Paddy ‘the Lurch’ Joyce near Drogheda, Ireland, in November 1997. McDonagh won and allegedly collected a purse of £20,000.

Lewis Welch from Darlington, an ex-boxer and one of the best current bareknuckle men.

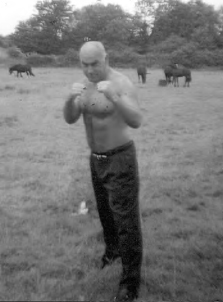

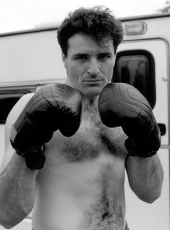

Big John Fury in boxing pose. He is 6ft 4in and weighs around 18st when not trained down.

Terry Ward, ‘the JCB’ from Darlington. Terry had one of his biceps nearly chewed off in a fight.

Ivan Botton, who stands 6ft 2in and is the champion of Nottinghamshire.

Charlie Moore, another top young gypsy fighter from the north-east who won a string of amateur boxing titles but gave the game up.

My son Shaun playing rugby for Uttoxeter. He’s not a fighter, fortunately, but on the sports field he takes a lot of stopping.

In my fifties and still throwing the bull-hammer into my big heavy bag. I had my last fight in 1997 and then turned my back on the bareknuckle arena.

My three dear grandsons: Bartholomew Gabriel, aged four, with his mother Maria, and on the right Nathan William, aged seven, and Joseph Samuel, aged four. I wouldn’t swap one of their smiles for all the gold in the world.

Returning to Hollington Quarry, the place where I won the title in 1972. We had to fight among the cut stone and junk.