Douglas Bader was a legendary if not iconic figure of World War Two. Views about Bader the man, the fighter leader and Bader the pilot have always been polarised and, to an extent, he has been a controversial figure – both during and since the war and, not least of all, through his involvement in the “Big Wing” episode in the history of RAF Fighter Command. This, though, is not a biographical study of the man himself but the examination of an event for which he is arguably most famous – being brought down and taken prisoner of war over France during August 1941. It is a story which has been famously told in his biography Reach for the Sky, and in the film of the same name where his part was portrayed by Kenneth More.

There can surely be few who are not already familiar with the dramatic story of his apparent mid-air collision with a Messerschmitt 109 and his desperate life or death struggle to escape by parachute as one of his artificial legs became trapped in the cockpit of his Spitfire. For decades this has been accepted as an accurate version of events that day and it is only in recent years that a question mark has been placed over what really happened. This book, then, is a thorough examination of events that day and the contents may be considered by some to be controversial in that the widely accepted “official” version of events is questioned, challenged and refuted. The author, though, does not seek to be revisionist. Instead, it is the intention to present the known and verifiable facts along with more recently discovered details of what took place that day. In addition, to offer up some hard physical evidence and proffer an alternative interpretation as to what transpired in the skies above northern France during Bader’s last fight. Notwithstanding the fact that this is not a Bader biography it would, nonetheless, be remiss not to paint a brief thumbnail sketch of Bader the man before moving on with this extraordinary account.

Portrait of Squadron Leader D R S Bader DSO, DFC, by Cuthbert Orde.

Douglas Robert Steuart Bader was born in St John’s Wood, London, on 21 February 1910, the second son of Jessie and Frederick Bader. Shortly after his birth the family relocated to India where Frederick worked as a civil engineer, although it was not long before the young Douglas was returned to the United Kingdom to be looked after by relatives on the Isle of Man. It was not until he was almost two years old that Douglas rejoined the family although, by 1913, they had returned for good to England. Upon the outbreak of war Frederick accepted a commission in the Royal Engineers and served with them in France, being severely wounded in the head during 1917.

Separation from his father thus became a feature of the young Douglas’s life, and this was compounded by his later admission to private boarding schools – first at Eastbourne and then at Oxford. From here he won a prize cadetship to the RAF College at Cranwell in 1928, where, in 1930, he was commissioned and posted to 23 Squadron at Kenley, then flying Gamecocks, and eventually to fly at the Hendon Air Display in 1931 as an aerobatic competition pilot. The following year, on 14 December, and still with 23 Squadron, he crashed at Woodley aerodrome after unauthorised aerobatics in a Bristol Bulldog and was seriously injured. As a result, he lost both legs; the right one above the knee and the left below.

Bader was invalided out of the service on 30 April 1933, unfit for flying duties, and obtained employment with the Asiatic Petroleum Company (later Shell) although, prior to the outbreak of war, he had agitated to return to active flying and was finally accepted after a test at the Central Flying School, Upavon, on 18 October 1939. With the rank of flying officer, and after a brief refresher course, he was posted on 7 February 1940 to 19 Squadron at Duxford, flying Spitfires, and then on to 222 Squadron, also at Duxford and also with Spitfires, as flight commander during March.

Bader’s career progression was, by any standards, extremely rapid and by early July he was promoted to acting squadron leader and posted to command 242 Squadron flying Hurricanes at Coltishall. It was here during the Battle of Britain that he began to make a name for himself, and although his early wartime career was spent flying the Spitfire it was as a Hurricane pilot that he made the majority of his victory claims. On 18 March of the following year he was again promoted, this time to acting wing commander, and posted to RAF Tangmere as wing commander flying to command the Tangmere Wing and, once more, flying Spitfires.

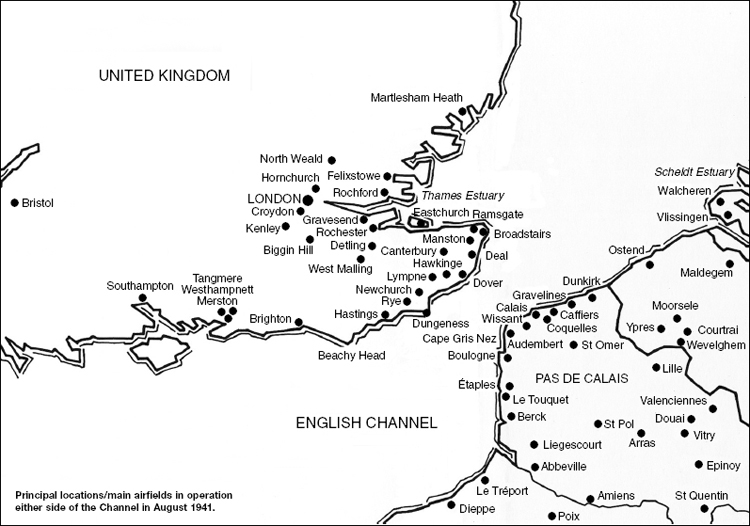

During the spring and summer of 1941 he had added to his tally of victory claims but, on 9 August, his fighting career came to an abrupt end when he was brought down over northern France and taken prisoner of war. To reiterate, the biographical detail of Douglas Bader’s life can be found, well covered, in a variety of other places although it is appropriate to mention here that his retired RAF rank was group captain with DSO and bar and DFC and bar, Légion d‘Honneur, Croix de Guerre and a Mention in Dispatches. He was made a CBE for services to disabled people in 1956 and appointed a KBE in 1976 and died suddenly on 5 September 1982.

Note: All times quoted are standardised at BST for both the RAF and Luftwaffe to avoid any confusion with Central European Time then being used by the Germans.