FRIENDLY FIRE – THE PHENOMENON EXAMINED

The term “friendly fire” is, perhaps, something of a misnomer both in the context of this book specifically, and within the usage of the English language generally. It is, however, terminology that is widely understood by the public at large and this is due, at least in part, to widespread media coverage of unfortunate episodes during the first and second Gulf wars. It is a misnomer in the context of this book, though, because it is in reality an exclusively modern American military term.

In British military terms “blue on blue” would be more accurate – this being a descriptive deriving from Cold War usage of blue map markers for Allied, NATO or “friendly” forces and orange ones for the enemy. More accurately, the Oxford English dictionary has another word for it; fratricide, defined as the accidental killing of one’s own forces during time of war, however this cannot be accurately applied to this case since no fatality actually occurred.

As World War Two terminology, though, neither the expression friendly fire or blue on blue is strictly accurate even though the actual phenonemon is as old as warfare itself. To be specific, non-hostile fire can be placed into three distinct categories; accidental misidentification, deliberate mis-identification (“fragging” to the US Military in the Vietnam era) or mis-directed fire which hits friendly forces often through errors of positioning. As a distinction, though, it is important to clarify that friendly fire should be regarded as fire that is generally intended to do harm to the enemy and not an event arising through accidental firing. Contrary to what might seem to be the case through present-day newspaper and media reports it is far from being a new aspect of 20th or 21st Century warfare that somehow first manifested itself during the recent Gulf conflicts.

In 1412, for example, at the Battle of Towton during the Wars of The Roses, strong winds caused arrows to fall amongst friendly troops as well as among the ranks of the enemy. At Waterloo, Marshal Blucher’s Prussian artillery fired mistakenly at their Allies, the British, and British artillery returned the fire resulting in considerable casualties on both sides. Throughout history, the list is almost endless and possibly the most infamous episode of friendly fire in the World War Two annals of the RAF was at the well recorded Battle of Barking Creek. Here, RAF Spitfires mistakenly engaged and shot down two Hurricanes resulting in the death of one pilot (Pilot Officer Hulton-Harrop of 56 Squadron) in an appalling blunder on 6 September 1939, thereby making Hulton-Harrop the RAF’s first fighter pilot casualty of the war – and by the hand of his own service. These, it is important to realise, were far from isolated incidents and it is also essential to appreciate that if the loss of Douglas Bader on 9 August 1941 were to be attributed to friendly fire then it would hardly be an extraordinary occurrence.

The history of the RAF in World War Two is liberally sprinkled with accounts of pilots mistaking friendly fighters for the enemy. On 5 September, 1940 for example, Pilot Officer Robin Rafter of 603 Squadron wrote of his experiences in combat that day, saying: “I very nearly shot a Spitfire down by mistake….” So, the evidence that it happened is certainly out there and these cases cannot all be put down to inexperience. Neither can the Battle of Barking Creek be attributed wholly to nervous jitters arising out of the uncertainty of the very early days of war.

Towards the war’s end, on 26 May 1944 a squadron of Spitfires attacked Spitfires of 43 Squadron over Lake Bracciano, Italy, resulting in the downing of Flying Officer Cassels who became PoW. Later, on 11 November 1944, we have another instance where Spitfires, again of 43 Squadron, were “bounced” over Padua, Italy, this time by USAAF P-51s resulting in the death of Flight Lieutenant Cummings and severe damage to another Spitfire flown by Flight Lieutenant Creed. The P-51 pilots all believed they had attacked and shot down Messerschmitt 109s.

Back to 9 August 1941 though, and we have an official RAF report for that date stating categorically that Spitfires of 485 Squadron were attacked by six other Spitfires during Circus 68 itself. Thus it should not be any great surprise or controversial revelation that friendly fire was involved that day. The evidence is there for all to read at the national archives in Kew.

The Luftwaffe were also far from being immune from such episodes. On 30 September 1940 Group Captain Stanley Vincent, RAF, observed two Messerschmitt 109s engaged in mortal combat near Dorking. What he had seen was another Me 109 engaging that flown by Leutnant Herbert Schmidt of JG 27, who was ultimately shot down wounded and taken prisoner when a single 20mm cannon shell exploded and blew his starboard tail plane clean away. No RAF fighters with 20mm cannon were engaged in that combat, and so the fatal shot was definitely German. The evidence is there to see in the preserved tail plane, testimony both to the lethal effects of exploding 20mm cannon shells and to the not unusual occurrence of friendly fire. A Luftwaffe loss more closely tied in time to the events of Circus 68, though, is related in the operations record book of 603 Squadron for a sortie flown later in the evening of 9 August 1941. It is noted that what was thought to be a Messerschmitt 109 was seen going down in flames over France and, it was believed, had been mistakenly shot down by the enemy.

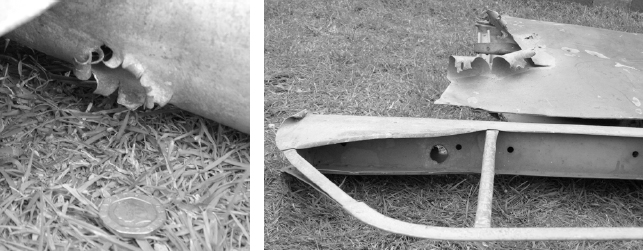

Two photographs showing the severed tail plane of a Messerschmitt 109 E brought down over Surrey on 30 September 1940. The assembly has been blown clean away from the aircraft by a 20mm cannon shell that has entered through the elevator and then exploded inside the structure of the horizontal stabilizer with devastating effect. Only very few RAF fighter aircraft were cannon-equipped during 1940, and none of them were anywhere in the vicinity. It is therefore safe to conclude that the destruction of this Messerschmitt was the result of accurate shooting by a cannon-armed Me 109 – thus providing us with an excellent illustration of both friendly fire and the deadly power of explosive cannon shells. A twenty pence coin gives scale to the exit point of the 20mm shell through the leading edge of the elevator. (Eddie Taylor)

After the author’s initial publication of the suggestion that Bader may have been a friendly fire victim, and the further investigation of that issue within the television documentary, a certain degree of criticism was levelled at those making such assertions. Some believed that such suggestions were “revisionist”, and if Bader said he had been involved in a collision then he had. Equally, if an RAF fighter pilot had said he shot down a Messerschmitt 109 then he obviously had. It was also said that the memory of great fighter pilots like Buck Casson was being tarnished and that the record of the RAF’s achievement, generally, was being besmirched.

The author strongly refutes all such suggestions, although putting forward uncomfortable facts like these is always bound to provoke some reaction. After all, one of the laws of the universe is that any action provokes a reaction! It is impossible, though, simply to ignore the reality of the facts and the evidence to hand. Equally, it is vitally important to look at all such information in a measured and balanced manner without letting sensationalism get in the way. As a fundamental point, then, let us accept that friendly fire is an unfortunate fact of war.

To put things into context for the RAF fighter pilot of the period, perhaps nobody could express it better than Wing Commander “Paddy” Barthropp when he described some of the difficulties faced by a young pilot who flew fighters into battle at that time:

He had total control of a 400mph fighter and eight machine guns – with no radar, no auto-pilot and no electronics. At the touch of a button he could unleash thirteen pounds of shot in three seconds. He had a total of fourteen seconds of ammunition. He needed to be less than two hundred and fifty yards from the enemy to be effective. He and his foe could manoeuvre in three dimensions at varying speeds with an infinite number of angles relative to each other. His job was to solve the sighting equation without becoming a target himself.

His aircraft carried ninety gallons of fuel between his chest and the engine. He often flew up to over 25,000ft with no cockpit heating or pressurisation. He endured up to six times the force of gravity with no “G” suit. He had about three seconds in which to identify his foe, and only slightly longer to abandon the aircraft if hit. Often, as in my case, he was only nineteen years old. He was considered too young and irresponsible to vote, but not too young to die.

Barthropp’s words, from one who was there, give a gripping insight into what it meant to be a fighter pilot flying a Spitfire into combat. All the same, he doesn’t mention the fear or the adrenalin-surged stress and absolute draining fatigue of it all. It is easy now, as armchair aviators, to read combat reports and other first hand accounts and not to appreciate fully elements like the cold, the overpowering noise of the Merlin engine, the incessant crackle of the headphones and the often unintelligible shouts from other pilots, the stress of being over enemy held territory, or over the sea, and listening and watching for any faltering signs from the engine. Not only that, but the mental strain of holding formation, looking constantly for an unseen enemy and the sheer physical effort and exertion of flying, too. To those on the ground it must have seemed a glamorous job. To some extent it was but more often than not the reality was far from glamorous.

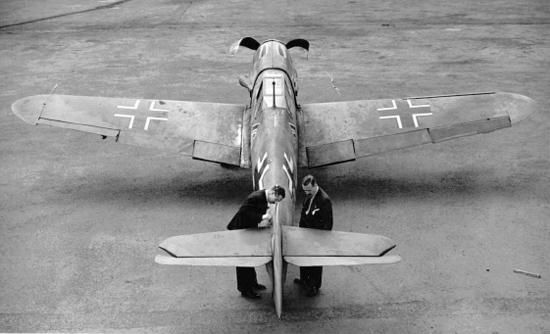

A camera-gun shot of a Spitfire caught by Gerhard Schoepfel of JG 26 on 27 June 1941. Compare this with the camera-gun image of a Messerschmitt 109 F caught by an allied pilot (right) and the similarities of both aircraft from astern, against a bright sky and in the high stress situation of combat and the difficulties faced by fighter pilots of both sides can be appreciated. (via Dr Alfred Price)

In Barthropp’s account he talks of the problems of sighting and identification, and the time in which he had to do both. A question of “kill or be killed”. If we factor in all of the other physical and physiological elements – which might also include blurred vision from the high “G” manoeuvring and the difficulty of seeing clearly and identifying a potential target against a bright sky or the sun – it is very easy indeed to see how these friendly fire events happened. We also need to look at the specific aircraft type against which the pilots on Circus 68 were pitched – the Messerschmitt 109 F.

The F model was a relative newcomer to the Luftwaffe stable and its shape was far more rounded than the earlier E model which RAF Fighter Command had faced in 1940. With its rounded wingtips, domed spinner cone and the deletion of tail plane bracing struts, the view from almost dead astern of a Messerschmitt 109 F is uncannily similar in some respects to that presented by a Spitfire from the same angle. Even during the Battle of Britain, when RAF pilots were fighting the Messerschmitt 109 E with its squared off nose cone, tail bracing struts and squared off wing tips some pilots, like Robin Rafter, were making split second errors of identification. Now, in 1941, it had become even more challenging for them.

If we suppose, then, that Flight Lieutenant Buck Casson was most likely responsible for inadvertently shooting down his wing leader that day it is important to look at this mishap in an objective fashion. First, Casson was a skilled, experienced, well respected and well liked fighter pilot – but as with all the other pilots that day he suffered the stresses and demands which Barthropp so succinctly encapsulated into his commentary. No degree or suggestion of blame is being attached to Casson here – or to any of the pilots involved that day in what may well have been terrible accidents resulting from the fog, speed and confusion of war. Who is this author – or any other – to lay blame at the door of a pilot who found himself in such a situation? Of course, there were many pilots (Casson amongst them, probably) who never realised their mistake. Some did, of course, and their inevitable sense of guilt or remorse can only be imagined. Perhaps, in a few cases, there may have been degrees of negligence or gross carelessness and even misconduct. In even fewer cases there may well have been deliberate acts, although the author is certainly not suggesting any of these factors came into play over the downing of Douglas Bader.

The first Messerschmitt 109 F to fall into British hands intact was that flown by Hptm Rolf Pingel the commander of I Gruppe JG 26 who crash-landed after combat at St Margaret’s Bay, Kent, 10 July 1941. Pingel was taken PoW but his interrogation provided a useful insight into Luftwaffe thinking in relation to the daylight missions then being flown by the RAF over France, (see Appendix N). The Messerschmitt 109 F was repaired and test flown by the RAF, but lost in an accident at Fowlmere on 20 October 1941.

To put things into overall context then, it is interesting to note that US Pentagon sources cite a figure of anywhere between two percent and twelve percent of all World War Two casualties as being the result of friendly fire incidents. From Vietnam, to Desert Storm and to the invasion of Afghanistan the figures stand at anywhere between fourteen percent to twenty-three percent. True, these are specifically US military statistics but there is absolutely no reason to suppose that the figures for other conflicts, other nationalities, or other forces are very much different. Any detailed examination of known mis-identification or misdirected fire episodes within the RAF during the 1939-45 period shows a surprisingly high incidence of such cases. One of these cases then, and based on all the available evidence, involved the downing of Douglas Bader.