4

GETTING HIGH

____________

John Popper

Blues Traveler harmonicist, singer, lyricist (sat in with RatDog, Weir’s band, June 2014)

I remember one time I didn’t have a ticket, but I went to a Dead show to try and find Bob (Blues Traveler bass player) at Brendon Byrne Arena. I went home for the weekend and asked my parents if I could borrow their car. I told them I was gonna get a pack of cigarettes. I got in the car and drove to the show to find Bob, figuring my parents would go to bed soon.

When I got to the show, I couldn’t find Bob, but I’d brought my harps because that always gets you out of a jam. Somebody gave me a tab of acid, which I happily munched down. I ran into some people and started jamming a little bit, but they were all playing Dead songs. I didn’t know any Dead songs, but that as okay, I could just play along. Then they started seeming really weird, their faces started melting, and suddenly I realized I might not have been thinking ahead when I ate that tab of acid because now I was really getting kind of lost. I was in this very big parking lot.

So, I started jamming with a different group of people to take my mind off it, and everybody knew these Dead songs. This was right after the show was over, but as far as I was concerned, the show was going on for eight hours. I was tripping! So this soon grew into a seething crowd of people who were just growing and growing, and they were all singing along. I started to get this closed-in feeling and figured I better get out of there.

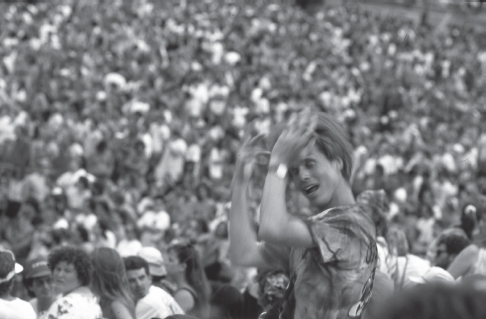

Vegas Dead show, May 30, 1994. The guy was totally a blur. Dancing his ass off. Wanted to capture the movement and energy. Courtesy of: Steve Eichner.

It turns out that Bob and Dave (Blues Traveler’s manager) walked right by that mob of people surrounding me on their way to their car to go home. So I’m wandering around, the parking lot is thinning out, so I decide I better just sit in the car until the acid wears off. I turned some music on real loud because, you know, it’s psychedelic. But all I could get was this cheesy … not Muzak, but it was just a really bad radio station to be tripping on, so I figured I better just get the hell out of there and drive home. A lot of bottles were in the parking lot, and I said to myself, “Well, I’ll just drive across. These are tires, they can make it.”

So I’m driving, and I wound up on the other end of this sports complex, it’s totally dark, and I can’t find anybody! Somehow, I got into this weird thing. I’m driving on off-ramps, and the whole time my car’s going boom boom boom boom. I figure that’s just me, I’m tripping. But about forty-five minutes later, I figure I better check. One thing you should never do, by the way, is drive under a blinking light when you’re tripping, because suddenly there are rabbits everywhere. So I get out of the car, and semi trucks are whizzing by. When they thunder by, it’s really freaky. So I check the first tire, it’s fine. Second’s fine, third is fine; the fourth tire is searing and melting into the ground, steaming, because I’d been riding on the rim for an hour. So I get back in the car, and I don’t know how to use a jack and have no idea where the spare tire is. So I’m sitting in the car going, “Shit. Shit. Okay. Sooner or later, a policeman will pull over and see if I’m okay. If I sit here long enough, a policeman will have to come.”

So I start preparing a statement for the policeman when he shows up: “Officer, I have a flat tire. Could you please send a tow truck? … Officer, I have a flat tire. Could you please send a tow truck? … Officer, I have a flat tire. Could you please send a tow truck?” No problem. I can say that.

Eventually, a cop shows up. I get out of the car and I walk up to him. He rolls down his window and I say, “I got me a big ol’ flat tire right over there!” For some reason, I just slid into trucker talk. The cop looked at me and said, “Ggrhzghgghrzgghrgghz,” and I swear to God, the cop had the head of a bee. And then he just drove away.

Finally a flatbed truck arrives, he puts my car on the truck, we’re driving away, and he goes, “That’ll be two-hundred-and-ninety-four dollars.” Of course I don’t have any money. So I had to call my mom at six in the morning from Newark and ask her for her credit card number to repair the flat tire I’d gotten after sneaking off with her car. Later, the flatbed truck guy was like, “Oh, here’s your spare tire!” So, I just drove home.

That was me going to a Dead show by myself.

Steve Brown

Filmmaker, Grateful Dead Records production coordinator (1972–1978)

There’s the whole conditioning factor of being around the Grateful Dead. If you haven’t already “warmed up” before you enter it, you better beware because their shit was really potent—both the pot and the acid. The acid was clean, but it was strong. And as far as cocaine and stuff like that, I wasn’t much of a fan, but it was also potent, of course. There were a lot of long nights in the studio where people continued and continued and continued to make things hopefully better and better, even though their minds and their voices might be going.

There were a lot of delays sometimes backstage just for the band to get in the space where they felt they could handle it and get onstage. Not that they weren’t themselves quite proficient at handling things at a high level. But even so, there were times when one or another person wasn’t quite ready. But with the Grateful Dead, I think they were the best overall-conditioned band for those kinds of instances where people—all of them or some of them—were high. Not all of them, actually. Pigpen didn’t get high; he had his alcohol. There were times when some band members weren’t doing stuff … and there were times when all of them were!

For me, personally, it was enjoyable because I kind of was able to know my limits and stay within control of being responsible for what they hired me to do. If I was just getting high as an audience member, that was a whole other thing. Then, no-holds-barred! But when you’re working for them, it’s a different kind of feeling. The band could get as high as they wanted. For me, it was about being there for them if need be.

I used to see Jerry check on people who were brought backstage who were kind of losing it. He was very kind that way—just making people feel comfortable, letting them know that things would be alright and talking to them in a calm sort of way. There were other times when Jerry in his own state would just walk away from that stuff because he didn’t want to deal with it. These people were just too tuned out.

But for the most part, weirdness was always kind of accepted as something to be dealt with in either a humorous or caring way—or both. That was always nice to see: an understanding of how these people had gotten themselves to and from their own extremes. That’s kind of the history of that whole era of learning to enjoy and/or survive your drugs. It became a thing of conditioning—knowing where your limits were. And you had to really live up to being part of the party and bring whatever you wanted for yourself. If you wanted to share it, great, if you didn’t, you didn’t. But there was always—seemingly in that crowd anyway—enough to share.

I remember one time we actually got our limo driver high. That was a good lesson to ourselves not to share anything with anyone who couldn’t handle it. This driver missed the turnoff, and if you missed the exit, it was twenty miles before you could turn around and loop back … all this at two or three in the morning after a show! We all sort of looked at each other going, “What have we done to ourselves by getting this guy high?

There’s always that kind of danger on the road because all of a sudden you’ve brought in an innocent party to your world of controlled chaos. So, unless they’re weird—or rewired—to be the kind of people we were because of conditioning, then sometimes these outsiders just kind of lost it. We were used to being high on the road and functioning under various states of altered consciousness, which is something neither to be ashamed nor proud of. In either case, it was a challenge. It often let to interesting times. In restaurants, there’d be what we used to call “mels,” short for “melons.” The Deadheads were included in our scene, but anyone outside of that was the world of mels. Whenever we stopped to eat along the way, we’d be kind of exposing ourselves to a very surreal world, and we had also probably altered ourselves, which added to it. In those kinds of experiences, you had to open yourself up to being able to step into them, survive them, and step out of them.

Jerry Miller

Moby Grape/Jerry Miller Band guitarist

Neal Cassady stayed at my house one night. He was quite a character. We were trying to capture sunlight with a whole bunch of mirrors! And we couldn’t find enough mirrors; we were breaking mirrors to make more mirrors as fast as we could find them, trying to slow down the sunlight, capture the speed of light. Of course, we were pretty well gone that night. We had them all through the house, little bits of mirror—glass all over the floor. And in the morning, we got up and made popcorn without a lid! Said, “Fuck it! This is fun!” Then when we came down, we had all this to deal with! Glass all over the floor, popcorn everywhere, oil paints all over the place.

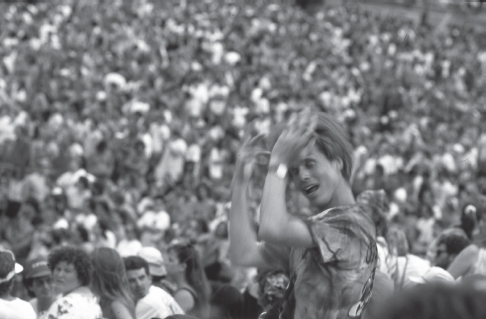

Bobby and Bill, Cal Expo, 1989. Couresty of Steve Eichner.

John Perry Barlow

Dead lyricist, cyberspace pioneer

During the time that Weir got involved with the Grateful Dead, I actually was off pursuing my own East Coast orthodox version of the same thing, at the hands of Dr. Timothy Leary. While Weir was taking the acid tests with Kesey and the Dead, I was off in Millbrook sitting in the lotus position and taking the whole thing very seriously in a spiritual sense.

I didn’t really know what Weir was up to, and then sometime in 1966, a guy we both knew at our school, Fountain Valley, wrote me a letter and said he’d seen Weir in a band called the Grateful Dead some place down in San Diego, and he thought I might be interested. I spent some time trying to find out who they were and how to get ahold of them, but surprisingly there was a disconnect between the East Coast and the West Coast. There was some intolerance between the two different strains of acid-head religion that had developed in each place—a tendency to view the other one rather harshly. The West Coast was much more about music and bacchanalia. It was just, “Let’s all take acid and see what happens,” and in its way, each way had its merits. I don’t fault either one of them at this point, but at the time I had my religion, and it made it hard to penetrate into Bobby’s.

But then the Dead finally came to New York in 1967, and I saw Bobby for the first time in three years. We hung around New York all afternoon. They were staying in this fleabag of a hotel. I didn’t know any of the rest of the band, and I spent the next two weeks with them, pretty much continuously. I brought them to Millbrook to meet Timothy Leary. I drove with Bobby, Phil, and Phil’s woman, a girl who was singing with Frank Zappa. God, I wish I knew what has become of her. She was amazing. Her name was Uncle Meat. Uncle Meat was a sly, witty character. Real sexy and real sly. She’d come up with these lines that were just so deadpan. Anyway, she came up to Millbrook with us.

Several things happened that day; one of them was that the Six-Day War broke out. And the other one was that Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released in New York, or at least that’s the first time I’d seen it in a record store. I got a copy and brought it up to Millbrook, so it was the first time that the Dead and Timmy heard it. We got up there and played it in this very Eastern Orthodox setting, with the lights just so, and the incense just so, and the cat piss on the Persian rug smelling like it did, and everybody being pretty reverent! We all sat around and listened to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It blew my mind. Timmy at the end of that record said, “Well, at least my work is over,” and it was pretty clear what he meant: that the idea of LSD was now pretty well loose in the culture and transmissible in some coherent fashion. Here was this rock-and-roll band in England—who were surely in a whole different mode—able to know exactly what had happened to us. It had happened to them, obviously. It was like control group in a way. “Yeah, it happens to them, too.”

Herbie Greene

R&R photographer

At the closing of Winterland, we were high, and I was with somebody who’d never been to a show or been high before. The way it was set up … it was stacks and stacks of seating. There were tiers. The thing was like starting from the top and going down, the colored lights and the people and all that stuff—it was like descending into Dante’s inferno. That was the impression I got. The Blues Brothers were playing, and there was all the insanity of the people around the band. They were very insane people. Lots of Hell’s Angels types and ruffians and people who were nuts. I mean, intimidating! The whole thing had an edge to it that was brinking on insanity. If you check out the Grateful Dead movie, it has that edge to it. You can tell, the nitrous scene and all that, and the cocaine and all that bad stuff. There’s that nasty edge to it.

Chez Ray

Chef for the Dead, native San Franciscan

I was careful drug-wise when I was cooking for the Dead. You become a specialist at the timing of what you do, those little windows of opportunities. So the things that I had to do, I would be very clear, and when I didn’t have to do anything, I had my window of opportunity to get high. On occasion, they would merge, and it became complicated. I remember cooking omelets once and I had to decide what to do—I very clearly saw three omelet pans in front of me, and I knew I had to choose which one was the real one I was actually cooking in. It’s such a wonderful memory. I think it’s hard to talk about with folks who don’t engage in or haven’t engaged in drugs much, or if they have judgment—but an incredible art takes place in your head, and it’s really quite beautiful. You realize that if you were in it and guided by the right folks, you could ride that energy. You can then play with it, and you can sort of put it to work with what you’re doing as opposed to having no control over it. At times like those, it takes charge of you, and then you don’t know what you’re doing. And that’s when it becomes nutty. But the scene backstage was … it’s like the cream of the crop. It was total professionals. You really had to be sharp.

On acid, it was interesting because there would be adjustments. The tools aren’t always there, which you learn quickly in that world. You have to be very sharp when you’re cooking, know what time people eat, what time they’re coming off whatever they’ve taken. So I was in touch with their experience—not that I would delve into their personal stuff nor do I talk about it ever, but it definitely was something I was aware of. Also, there’s a sense of when people have exhausted that particular evening—it’s early in the morning, and perhaps it might be good for them to eat, for example. So I become my own Jewish mother to everyone!

You can lose sight when you’re high—especially in the rock-and-roll world because it’s such a fast-moving thing. So there’s a responsibility from wherever you sit within the circle, and mine was to ask, “Do you need to eat?”

Tom Constanten

Keyboardist for the Grateful Dead, composer

I think the role of drugs is overstated for both good and ill. I think I can say categorically that drugs really didn’t do much ill. People who would sit around and get stoned all day would probably like to sit around all day and do nothing anyway. They don’t need drugs for motivation to do that—it just helps them do it a little more enjoyably, perhaps. Or entertainedly. Likewise, I think there’s a lot of inflated claims for all the glorious things that came from drugs. All they did was open doors for things that people were involved in anyway.

Drugs were a fun part of the whole scene. I’d hate to see it without drugs, but I don’t think they were the crucial genie in the bottle that either the detractors fear or the proponents claim. Much ado about nothing—in both senses. I mean, even a good acid trip can be like a Saturday-night drunk; you open the spigots and flush everything out, so to speak. Which is a great thing to do. I think it’ s better to have that than not have it, for sure.

To my knowledge, I was the first person to transport LSD to Las Vegas in the early 1960s. They had all these affectionate names: “Blue Lagoon” in a little blue vial. These brown pills they call “Brown Reknown.” There was “Startling Burgundy” and “Plum Pretty,” a purple liquid. There were the capsules that looked empty, and I called them “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” I was a dealer to the dealers. Crap dealers, roulette dealers, a lot of good friends in those times.

Of course, acid was still legal back then, as was peyote, which you could virtually mail order. What a great way to grow up! We’d go out into the desert. There are some wonderful places out there where you can’t be sure what planet you’re on by the time you’re floating. That was the milieu I was used to when I came to San Francisco, People here were taking acid to hear music. It sure helped rock music do what it does even better.

I remember one time when I was playing with the Dead, we had a gig in Boston. Jerry, Phil, Owsley, and I were out dining. Owsley was pouring tea for Jerry, and it overflowed the cup, it overflowed the saucer, and it started overflowing the floor! Jerry said, “Here’s the man who we’ve been entrusting our body chemistry to. Look what he’s doing!”

Pigpen was the best person to have with you when you were having a trip. He was a princely, gentle person. Utterly wonderful. If you got dosed accidentally, which happened to me once or twice, he was sensitive, very different from what you might think if you just saw his picture.

Rick Begneaud

Cajun chef for the Dead, artist

My friend Michael Nash had two tickets at Shoreline, really good seats, maybe twelve rows back on the aisle in Section 102. But right before the show, Michael’s wife decided to come, so we’re three people in two seats. The show starts, “Hell in a Bucket”—boom! A guy turns around and says to me, “Outta here!” Michael felt bad because he’d invited me to the show, but I didn’t care because I was feeling pretty groovy at the moment. So I get out of that section, and I go up and I’m cruising around. I get to the top of the section, and I just start hopping over chairs. Soon I’m right back down in the middle near where I started.

At set break, I’m thinking, “Man, I feel so good—if only I had a mushroom right now.” A minute later, I’m taking a pee, I look over on the floor, and somebody had dropped a mushroom—not in the piss part but out in the clean part. I take it, and I’m cruising around. I’m just having a blast. At drum break, I go backstage and walk onstage, and I go into Jerry’s little tent, and I’m hanging out with Steve Parrish, Jerry, and Bobby. Drums are going crazy out there, and this beautiful conversation, this rap between these guys, was happening, and it was so very cool.

I remember Weir takes a bottle of vodka and says, “Medicinal purposes,” right before he takes a swig. Jerry’s having a White Russian, and Parrish is carrying on about all kinds of beautiful, crazy stuff. I’m just sitting there. I’m good, really high.

Then, the crazy, crazy drums are winding down, and it’s about time for these guys to go back onstage. So they start to gather their molecules, and Jerry looks out at the stage and looks back at us and says, “Well boys, we’re going in!” It was like they were going to battle! It was so cool to be in that little place at that moment. I’ll never forget it. It was truly special to be that close to the center of the source.

Weir once told me something that always stuck with me. He was playing flag football with Hunter S. Thompson in Colorado somewhere, and Thompson said, “Death before dishonor. Drugs before lunch.” I think they may have even had T-shirts made for the team. “Death before dishonor. Drugs before lunch.”

Will Sims

Waverly, Alabama

The wheelchair section was really a wild experience. I remember—I mean, this is all kind of hazy. It was all kind of one big thing. We were all youngsters and doing acid out in the parking lot for the run of shows. Anyhow, one night we went, and I’m totally high when I get to the wheelchair section. I was just cookin’. By this time, me and this paraplegic guy were super tight. He was trying to hook me up with his stuff. He looked at me at one point and said, “Dude, you are buggin’ out. Reach into my bag!” He had this Crown Royal bag full of pill bottles. He said, “Reach in there and grab the—” I can’t remember if it was valium or what. And I’m digging through the bag and showing him the bottles. I can’t see what the fuck I’m doing! And he’s like, “Yeah, that one! Take one of those!” I put all his shit back in his bag, and I take one. By the second set, I’m just floating on a pillow. I was no more high than I was before I hit it, but I didn’t want to move. I just sat back and had this moment. Me and my paraplegic friend were just sitting there in our wheelchairs, looking at each other and smiling. It was awesome.

insert text:

Kathleen Cremonesi

author Love in the Elephant Tent

I have one moment that is glued in my mind. It was early on in my Dead experiences. This friend and I had gone down to Chula Vista to see a show. We took yin-yang blotters, LSD—and we do not remember the entire show!

When we came back to our senses, we were sitting against what I think was a chain-link fence at the edge of the concert. We were staring at this guy who was maybe twenty feet away, who was actually watching the show. He had a nose that was so, so large. He was holding this stick of incense in his hand, bouncing to the song “Satisfaction” very gently, and there was this stream of smoke coming up from his incense going straight into his nostrils. I have that image glued in my head! I can see it perfectly, absolutely perfectly. The Dead were playing “Satisfaction” and everything was beautiful and it didn’t matter that I didn’t know what I had been doing, who I had been speaking to, or if I was even capable of speaking or dancing or anything for the past who knows how many hours. I mean, there was no worry that something awful would happen to you if you were somewhat incapacitated.

No matter how high I got—and I did—I never had a bad trip, and I think that has to do, obviously, with my own state of mind but also the place where I was. I always seemed to find this great piece of mind, like it was almost magical. Any questions or any thing that was unsettled in my life, through psychedelics, through that process, I was okay with myself, with the world, with my place in it. It just seemed to work everything out.

Obviously psychedelics aren’t for everyone, but we all know that cultures have been using them for thousands of years to get in touch with themselves and with the natural world. And I can honestly say that I wouldn’t be the same person that I am without their affect on me, my life, my outlook on life. They absolutely helped me figure out who I was and what I wanted—even if I didn’t know exactly what that was yet, they opened the doors to allow me to get to it.

I remember this letter that I wrote to my mom, and I bet I have it somewhere, telling her that I have seen the light and something about I understand how to be happy in life and it all makes sense now. I need to find that letter, just for myself! And my mother said that when she read it, she thought I had joined a cult of some kind! I was talking about not the Grateful Dead, but in my mind I was talking about psychedelics even though I didn’t mention that to her.

I’d never been physically ill on drugs, but once my husband and I came back from the circus in Italy, I tried psychedelics three or four more times. Each time I tried them, they made me physically ill, no matter if it was mushrooms, LSD—it made me physically ill. I never had any mental problem, I was still happy, but sick. My body just said no and I have not done them since.

Chuck Staley

Restaurant owner, Roswell, Georgia

Bathrooms were always a place you tried to avoid because it just gets scary in there! I had some bad experiences. I was at a show one time, and I get to the bathroom, and I was really messed up. It was during drums and space. I’m in there saying to myself, “You gotta get your shit together.” I think I was standing in front of the mirror for an hour.

This dude said, “I just want to tell you something. My buddy just came back to my seat and told me about some dude who was staring at the mirror, and that was twenty minutes ago. And I think it’s you. Have you been in here for a long time?”

I said, “I don’t know, I have no idea.” So then I try to go back to my seats, but I never even came close to finding them again. I randomly just found my buddies out in the parking lot later.

I’ve had about three shows where I’ve had to leave because my shit was just out of control. I’m just like, “I gotta go.” I was blotto. I just couldn’t take it. My friends were like, “What?” And I said, “I can’t deal with it today, I gotta get out of here.” So I’d go out to the parking lot. A couple times I found a ticket and went back in, but other times I’d just wander around. You could usually hear the show, unless it was an indoor venue.

One time I was in Buffalo, and they opened the show with “Crazy Fingers,” which was completely bizarre. At this point, we were doing liquid acid in the eye. We were blistering. I was twenty-one. I grabbed my buddy Jim and said, “I gotta get outta here.” He said, “What’s going on? Let’s go sit down; you’ll be fine.” We go sit down, he looks at me and says, “Yeah, you oughta just go now and get outta here. You’re a fuckin’ mess!” So I just went outside.

I’ve had experiences when the show was over and I was like, “Why is everybody leaving? What happened to set break?” And they said, “We already had set break.” I was high as fuck.

We’d always go in there with the most minimal amount of things. No matter what the temperature was, we’d try not to wear a jacket because chances are we weren’t going to bring it out with us. I always had a piece of paper and a pen. Most times I tried to put my drugs in my hat.

One time I put a strip of acid in there during the day and totally forgot, like a dumbass. I was sweating bullets. We’re at the car getting ready to go in to the show, and my buddy says, “Hey, where’s that blotter?”

And I’m like, “I don’t know.”

He says, “Did you take it out of your hat from last night?”

I’m like, “Oh, man, so that’s why I’m so fucked up—from the sweat!” It was probably fifteen hits!

I could tell stories about this kind of stuff for hours—just funny-ass stories. Going to Denny’s after a show and just sitting there, and the waitress is like, “Uh, you’ve been here for five hours.”

“What?”

She says, “You haven’t done anything but drink water for five hours. It’s 5:30 in the morning.”

Just … no concept of time, of anything. That’s what we loved about it because when you’re on tour, you kind of lose track of time and place.

Billy Cohen

Student of Bill Graham, soldier in the music biz, poet, dreamer

The summer of 1988, I was hired by Bill Graham. I had moved out to San Francisco and was put under the tutelage of Peter Barsotti. I worked the whole Bill Graham/Grateful Dead summer. My gig working production was all the backstage setup stuff, which was called the “ambiance crew,” which to the best of my knowledge is only a Bill Graham Presents assignation for backstage production. Obviously, there was a whole lot of crazy going on!

The Laguna Seca shows in 1988 were total madness. David Graham tried to throw David Lindley out of backstage because he didn’t recognize him! Laguna Seca was so full of whacky stuff. Appetite for Destruction was a big record at the time, and David had this van, and I just remember driving it around Laguna Seca, like on the track and all over the place, and just cranking out Appetite for Destruction in the middle of the whole Dead thing. It was really a trip.

We were David’s crew, “SPAT”: Special Projects Attack Team, which had been previously some of the old-guard, Bill Graham people, like Peter Barsotti and those guys. We were designated SPAT in 1988. It was me and two other Delta Phi brothers working for David, and there were just all kinds of crazy Ninja jobs. At one point, we had a chalk machine, and we were trying to line a camping and parking line basically on the side of a crazy steep hill. It was bananas.

My wife Colleen’s birthday is August 5, and Jerry’s is August 1, so Jerry’s shows would often have these little backstage birthday things where they’d both be there—Colleen worked for Bill Graham—and everybody wished them a happy birthday. One particular year, Jerry was playing the Greek Theater in Berkeley on August 5, and they put me on that show, but they put me on the crew call kind of late. I had a stage pass, but then the union guy did a head count and said, “You’ve got one too many.” The way it worked for shows was that you must have half union and half BGP on the stage crew. So they cut me.

I’d been there from the beginning of the day, I had a stage pass, but now I wasn’t working, I was just there. So I kind of traipsed around; I got everybody to sign a birthday card for Colleen. Then it got toward the show starting, so I dosed. I missed the whole backstage birthday thing with Jerry and Colleen because I was just “whoooo!”—tripping face! So finally the show starts, and all of a sudden I’m onstage smoking a fat joint. The Barsottis, Dennis McNally, and some other people are there. It’s a heavy scene because Brent has just died, it’s their first show back, and it’s Jerry at the Greek.

I’m having a great time tripping, smoking grass onstage with the Jerry Garcia Band playing. Bill Graham comes onstage, gets ahold of me and pulls me offstage. He sits me down at a table backstage, and I’m flying on acid. He says to me, “What do you think you’re doing?”

I said, “Well, I was put on the show, I came to work, I worked, they realized that I got added to the call, and it put the BGP Union out of balance, so I got cut. But I have a stage credential, and I was legitimately cut, so I’m not supposed to be working anymore, and they told me I could hang out for the show, so I’m hanging out.”

He says, “No, you don’t do that.”

I said, “Okay.”

Bill said, “Look, there are these people who have worked their whole life doing this. There might be a guy out there in the parking lot, he’s a blue coat, he loves the Dead, and it’s his dream to be onstage smoking a joint. You can’t just show up here and, two months later, live his dream. That’s not fair.”

What Bill understood was that for there to be peace in the ranks and for me not to be hated and for him not to be resented, you didn’t open the kingdom to a relatively new guy like me. That’s just not fucking happening. I got it. He was right. He was wise. I understood. I accepted it. But it was this intense thing because I’m tripping on acid and had to explain that I have a legitimate stage pass, I was working, I was legitimately cut for a legitimate reason. So I explained myself accurately and fairly. I was not in trouble, but that was just the reality. He was laying it down. It was the way it was, and that was it.

So that was that. I had survived, and I was greatly relieved that even tripping balls I could still explain myself very clearly to the boss and have it be acceptable and now no longer be in trouble. I don’t want to be in trouble with Bill—no one wants to be in trouble with Bill! Now it’s all cool, and I’m just hanging out with Bill backstage.

At the back of the stage at the Greek Theater there are these giant swinging load-in doors. We go back there, and Bill is pulling the door open. All of the Jerry Band crew guys are like, “Who the hell is opening that door?” They all come rushing out. There are all these little spaces called pipe and drape—curtained-off little spaces and metal pipes.

Anyhow, the crew guys all come rushing out to see who’s got the chutzpah to come to the back of the stage. Jerry’s onstage—who the fuck thinks they can come back here? They come charging out, among them Parrish, of course, and they’re going to kill whoever is doing this. Who has made a big mistake? We’re gonna fix them!

Well, it’s Bill, right? So now they’re all at ease. It was amazing because they were like army ants swarming an invasion, but when they knew it was Bill, they were totally at ease. It becomes clear that they’re on Bill’s stage, and Bill didn’t need to do anything except sort of poke his nose in and let them know he was there. He didn’t want to hang out there. He just wanted to open the door and do that—and he probably did it for my benefit, too. He was flexing. He was showing off.

I’m still tripping balls and I’ve seen this whole scene, and I look at the old man and I say to him, “You know, you are the biggest monkey with the biggest nards.” And he puffed up his chest! It was very animal. From my tripping mind, that was the best way I could describe it. I say that to Bill, and he grins and we hang out for a little while longer. Then he’s gotta go do something. Having been corrected and instructed and having done my time, he sent me off to enjoy the rest of the show, so I floated around out with the crowd.

Now it’s the end of the show, I’m still super high, and everybody’s basically gone. Jerry and Manasha are leaving the venue, and they walked out from the side of the stage, out sort of in front of the stage, right where I was. Brent had died nine days earlier, and I said, “Jerry, how you doing? This was really heavy. Was this a healing thing for you to play this show? I know for all of us out here it was heavy, and it felt good to have you playing.”

He said, “Yeah, absolutely man. I really needed to play; I really needed this show.”

It was a really far-out moment.

Carrie Rossip

Talent manager

When I was eighteen, I transferred from New York City to the University of California at Berkeley for my junior year of college. I had chosen Berkeley solely for the location; I knew I had to be near the Dead; therefore, I chose in the Bay Area. I arrived in the fall of 1976. I moved into a house on Ward Street with a New York friend, Iris, and three guys who were all friends of Iris and her sister, Rochelle, none of them Deadheads.

In October, I went to my first West Coast Grateful Dead show. The Day on the Green was a pair of Saturday/Sunday concerts at the Raiders’ football stadium – the Oakland Coliseum. The Dead opened for The Who, which I found strange, and made stranger by the fact that the show started at 11 in the morning. None of my roommates were interested in joining me at the shows, but I had become acquainted with a group of Deadheads. Like me, they were transplants from the East Coast to the Bay Area, or as we felt about it: The Holy Land. I went by myself to the shows, knowing I would see them, as always, just behind the soundboard (but in front of the tapers).

The second day, I made my way up to the very front of the crowd with one of my new friends, but we were soon separated in the crush. With my arms draped over the divider, it felt like all fifty thousand people were pressed up against me from behind. I was very high, tripping on some strong liquid acid I had taken at the start of the show, but I felt safe. The crowd was made up of my Deadhead family. Even if I didn’t know them personally, in my mind we were all “known” by one another.

Being with the Dead, especially so close to the stage and that high on acid, felt magical. I had seen the band maybe twenty times so far, mostly the previous summer. It was just a fraction of the hundreds of shows that were to come; I already knew their music was to be the soundtrack of my life. I had been listening to their albums throughout junior high and high school, and their music felt like home to me—certainly more like home than my home ever had. Their music lifted and caressed me; it took me to amazing heights and then always let me down gently at the end of the night.

They opened with a rollicking Jerry song, “Might as Well,” and then went into Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried,” with Bobby singing the part of the wayward cowboy. A few more bar songs and cowboy songs and even Chuck Berry’s “Promised Land” – those first-set songs with Bobby and Jerry trading vocals. By “Dancing in the Streets” the acid was really coming on. They moved into “Wharf Rat,” a sad ballad about a wino who’s lost it all and is telling his sorry story. “Wharf Rat” is more of a second-set song, and as it led into a trippy jam, I began to have a lot of eye contact with Jerry, who I now knew was singing the song to me. Later Phil and Donna noticed me, too, and I came to feel they were my protectors, watching over me from the stage. Phil’s bass spoke to me; I literally saw letters forming words of encouragement, coming out of it over the heads of the security guards and right to me. Jerry’s smile, I knew, was just for me. And the spray from Bobby’s mouth as he sang turned into diamond droplets floating towards me.

Unfortunately, when the show ended a few hours later, I was just as high, and the Dead had left the stage. But I was wedged in against the front divider, and moving seemed all but impossible. I was dismayed to realize that I no longer knew anyone around me. Not only that—they all looked like complete strangers, people I would never know. Bikers and girls with big hair and too much makeup had replaced the flower children and hippies. What had happened to My People?

And then The Who came on. Now, I like The Who as much as anyone, and respect the skill and artistry of their musicianship and the near-perfection of their songwriting. But when they took the stage, the preening and self-regard of it all stunned me.

There was Roger Daltry lasso-ing his mike in huge circles, marching and posing, Pete Townsend banging his guitar chords like the spinning out-of-control hand of a large clock, John Entwistle solemnly grandstanding, although surprisingly, the enfant terrible, Keith Moon, seemed the most normal. After the humble non-performance performance of the Dead—more of a channeling than a show—The Who seemed like a group of circus performers. And once I let that thought enter my mind, they began to appear (thanks to the acid) as actual circus performers, and for that matter, quite sinister ones.

With that revelation, I began to feel the bodies now pressing up against me, and even rubbing up against me, and realized in a panic that I had to get out of there. And so, I began fighting my way out—pushing toward the back, as everyone else was pushing toward the front. I tried not to look at the faces of the people I was pushing against; I knew none of them wished me well, and I was determined to get out of there without incident.

It seemed to take forever—an epic journey—but eventually I was safely in the back of the stadium with space to breathe. It dawned on me just how high I was. I found the Deadheads I knew, as always just behind the soundboard, and calmed myself in the safety of their circle.

I didn’t stay for the rest of The Who’s set.