6

GETTING AROUND

____________

Dennis McNally

Publicist for the Dead thirty-five years, self-proclaimed Deadhead, more than nine hundred shows

My favorite moment ever with the Grateful Dead that didn’t involve them being on stage playing music was … 1987, we had a tour that we nicknamed within the organization “The High Altitude Tour” because it started in Denver at Red Rocks and then went to Telluride and then down to Phoenix but then to Park City, Utah, and then to the Calaveras Fairground in California, which is up in Sierra Nevada. So it was all mountain shows. They were day shows, so we left the stage in Telluride and headed for the airport, which is 9,000 feet or so. It’s up there! And ordinarily the Grateful Dead flew in a G3, which is an elegant corporate jet, but because of the altitude, we had to take a different plane. The air was way thin. And it was interesting because, of course, the whole point of a G3 is to remind you that you’re rich, and you face inward—all the seats, the focus is inward.

This plane reminded me of the original DC-3: one seat on each side of the aisle. Everybody had a window, which meant everyone got to look out the window, clearly. So we get up in the air, and the pilot comes on and he says, “Do you guys wanna go straight to Phoenix or do you wanna be tourists?” And everybody said “tourists!” of course. And joints are being passed and beers are being drunk and it’s a happy time, relaxed. And the pilot said, “Okay, do you want to see the Black Canyon of the Gunnison or Monument Valley?” and everybody says, “Monument Valley.” Sometime look at a map—draw a straight line from Telluride to Phoenix and you’ll see you’re passing over some of the most amazing (I’m a map hound, anyway)—territory in America, really.

All of southern Utah and Monument Valley is a flat valley with four or six of these buttes. You’ve seen it a million times—in Back to the Future, car ads, every John Ford western—not every, but many were shot there. It’s an essential part of American culture. And it has these giant buttes; they’re called “the mittens” because you have the very tall verticals, which look like the fingers and then short sticky-out parts at the bottom that are like the thumb of a mitten. When you see an image of them, you’ll go, “Oh! Oh, that!” And, I might add, it’s all sandstone so it’s very sensitive to light and to the colors.

And so we get to Monument Valley—and the pilot peels into a dive! Those buttes rise about 2,000 feet above the valley floor, and we go into a dive at 1,000 feet, and we have buttes above us and buttes below us. It’s now just about sunset, it’s twilight, and the sandstone is bleeding color! There are yellows and oranges and purples and reds, and it’s just beyond spectacularly beautiful. It is awesome—and I don’t use that term. I loathe that word, the way it’s been abused, and I use that word most specifically and most carefully. It was just an extraordinary experience.

But there was a lot more—because of the people involved. We were all just gap-jawed! Taro, Mickey’s son—I would guess he was six or seven then—is sitting in the pilot’s lap, and according to the pilot is steering the plane! Meanwhile, in Denver, Mickey has acquired a six-foot-long boa constrictor that he names Cosmic Charley, who eventually got to about fifteen feet at his ranch, but at this point is a relatively young six-footer. And he’s weaving his way up the aisle, which means he’s running into people’s feet and either scaring the crap out of them or crapping on their shoes.

So it’s a circus now. And Jerry—who is to my immediate left and behind me—is giving, I swear to god, a film history lecture on elements in the context of John Ford films. And I run up to him and I say, “Yeah, yeah, yeah! That’s the opening shot of Stage Coach,” and things like that, which is just perfect.

For me, in some ways this moment summed up the entire Grateful Dead experience. Traveling with the Grateful Dead … There was a level of madness and incredible knowledge and insight. I don’t think you’re allowed to take planes that low legally, I have no idea, but in any case—how often does anybody get the chance to fly into Monument Valley at 1,000 feet? The idea of being in the middle and being able to look up and down and see these buttes—that’s what registered on my brain. There was no way other than being with the Grateful Dead that I would ever have had this opportunity.

And I was grateful.

Kathleen Cremonesi in her VW bus, which got her to over 100 shows. Courtesy of Kathleen Cremonesi

Kathleen Cremonesi

Author of Love Inside the Elephant Tent

My VW bus broke down all the time. I used to have these pink dishwashing gloves that I would use to work on it. They worked, you know? I remember being at some house in the Bay Area between shows, and some guy was noticing my pink gloves who said, “A, I can’t believe you’re working on your bus; B, I can’t believe you’re doing it in dishwashing gloves!”

One time in Red Rocks, the brushes that charge a VW engine, charge the alternator, generator—whatever it is—were not connecting. They were too worn down and it wasn’t charging. Some guy—I mean the creativity of Deadheads is astounding—some guy sits down as I’m trying to figure it out. He says, “This is what we’re gonna do …” and he picks up cigarette butts off of the ground and cleans the paper off. We pull the brushes out of their little holders, stick cigarette butts behind them so they’ll push these brushes out further so they’ll actually touch the spinning part of the alternator—whatever it was—to charge the engine properly. So there I am in my pink dishwashing gloves, stripping the paper off of cigarette butts to fix an engine. And dammit if it didn’t work!

Whenever I was traveling, if I saw a Deadhead on the side of the road, I would do everything in my power to help them, take them somewhere, go get them gas, stop, keep them company, whatever was possible. There was the community that was on the Dead lot, of course, but it was outside of it, too. I mean you could be hundreds of miles to the next show, going across country between shows in the North East and trying to get back to Stanford University for shows. I was always helping people broken down on the side of the road—even though it probably made me late for the shows.

One time there were four of us driving between California and Red Rocks, and we were really poor. I sold beadwork at shows to make money, nice beadwork, but it doesn’t always sell. So traveling between the Bay Area and Red Rocks, I had four people with me and we literally had sixteen cents between the four of us! We had no way to make money until we got to a show. We tried selling jewelry in a MacDonald’s parking lot. That doesn’t work! Somebody told us that you could go to churches in towns and they would give you a voucher for a local store, and a voucher for gas—basically enough money to get you out of town.

So we were able to do that the entire way, depending on the generosity of these churches—except in Nevada where marijuana was a felony at that point. We went to this church and they said, “Here’s a voucher for the grocery store, and here’s where you get gas.” We go there to get gas and it’s the police station. You had to go in this chain-link fence to get gas and once we’re there, you can’t just stop in front of the police station and then take off without getting some attention that you don’t want. So the other three people in the bus got out and hung out under a tree or something. I went in the chain-link fence to get gas. And, of course, right above my gas tank I had a Steal-Your-Face with a marijuana leaf on the skull. I’m just looking out of the corner of my eye at this cop who was staring at that sticker as he’s putting the gas in the tank! He steps around to the back of the bus, reads the stickers, “not all the kookies are in the jar”, I’ve got the Gooney Bird, which was the first LSD I ever tried. The cop filled the gas tank with whatever amount they had allowed and sent us on our way.

At places like Alpine, you didn’t need to worry what’s happening after the show, it’s just all beautiful and easy to get around or home. But at places like Chula Vista and Long Beach, there were super fresh, young Deadheads. After the show, all of a sudden everybody’s leaving, you don’t have your own transportation, the funky folks kind of come out—whether it’s the funky side of a Grateful Dead show or what it attracts out of the community or just the weirdness, the tweakers of the community wanting to come there to see how they can profit in some way, how they can take advantage of the high little hippies.

One time in Chula Vista after a show, we were in the parking lot and the scene was getting weird. We had our thumbs out and people were just passing us by and passing us by. Then Volkswagon bus stops, it’s already filled but they invite us in. Turns out they’re going close enough to where we live that they will take us home. We get in the back, lay down on whatever bed they had back there, and the engine starts doing it’s like “ch-ch-ch-ch” like a VW bus does, and that was it. They just whisked us off to home.

The same sort of thing happened in Long Beach, except this time it was a Volkswagon Thing. Long Beach can be a dirty, gritty town in places, with no way to get home. Again, everybody’s leaving the show, it’s cold, we’re coming to our senses and saying, “Now what?” We had no idea about public transportation. We might take rides with people we really shouldn’t take rides with, just to get moving. This guy comes up in this orange, open VW Thing filled with Cherimoyas in the back that he’d been giving out at the show. We labeled him the “Cherimoya Man.” We’d never seen or heard of a Cherimoya fruit. It’s a wonderful little fruit with the consistency of a pear but the flavor and sweetness of a strawberry. So he peels them, hands us these big, beautiful fruits, invites us into his Thing, and drives us home.

Those types of things just happened over and over again, where you could be susceptible to so much and nightmares could’ve happened. But they never did on tour.

Steve Brown

Filmmaker, Grateful Dead Records production coordinator (1972–1978)

While you’re on tour with the Dead, things happen—like being on airplane flights that lose altitude all of a sudden, and you fall hundreds of feet. There was a time when I was promoting the Grateful Dead’s first album release, Wake of the Flood, and I had to go to all these cities and do a preview playing for all these distributors before the album actually got released. Then the distributors would buy it, stock it, and sell it to the retail market. So when I was doing that, there was a lot of travel—not necessarily coordinated with the Grateful Dead’s tour, but I tried to be in the towns where they were playing so I could invite these distributors to shows. You’re schmoozing the people and the scene, taking them backstage, introducing Jerry, giving them primo tickets for their colleagues—whatever.

So there was that world going on, and because of that sometimes I had to be in four or five cities in one day. I’d be in four airports in one day. It got really crazy! Even though the weather might be bad, you end up saying, “Well, I have to be there,” and you go anyway—even though it’s the middle of Kansas, and there are tornadoes everywhere. So yes, sometimes travel was a little bit scary.

I used to drive Jerry home a lot after rehearsals or whatever, and it was just us laughing a lot, talking about Twilight Zone episodes and such. One time around 1973, we went through Tam Junction, and we were turning off to go up to Muir Beach, and the car ahead of us drove off the road into a ditch. There was a car rollover incident off Skyline Boulevard that occurred in Jerry’s life in the early 1960s, and a guy died in it. That story always kind of stuck with Jerry when he saw something or heard of something like that happening. I was driving my van, Jerry was sitting in the passenger seat, and we came upon this scene. You could see his face totally change from having fun and laughing to totally dead serious. We jumped out of the van, ran to the car, and tried to make sure the guy was okay and that the car would be able to get out of there.

When I was on the road with the Garcia Band, we would tour by flying into an area like the Northeast, rent a car, and drive to the gigs at colleges and clubs. They were usually big cars like a Cadillac or a Lincoln because, in most cases, I would take the whole band. I would drive these guys around for hours, and I’m hearing Ron Tutt in the back telling Elvis stories to Nicky Hopkins, who’s telling Stones and Beatles stories, and Jerry soaking it all in and adding his quips. It was a rock-and-roll dream to be with these guys on the road traveling in an intimate situation like that for many miles before we got to the next town, and then going to dinner, to the hotel, and then to the gig.

Sometimes driving on the road in rental cars—say, out in the Midwest—it would be hailing or whatever, and you’d wind up being totally disoriented at night after a show. You’re trying to figure out where the hell the hotel is, and you end up at a donut shop. Not only do you get a nice snack while you’re there, but you’d also ask somebody where the hell you could find this damn hotel you were staying at. They’d point you in the right direction, and you end up with the local police having coffee and a donut!

There were definitely weird moments traveling with all those guys—eating, drinking, smoking, normal bodily functions, and all that. In a group of men like that, certain gases would appear at various times and usually at inappropriate moments—especially if you were in a small area, of course!

Rick Begneaud

Cajun chef for the Dead, artist

In 1981, my pals and I were planning on going on a little Dead tour in Lafayette, Louisiana. One night, drunk, I see my friend Tammy Milam, who’s one of my best friend’s sister. She just got a little Honda something-or-other, brand new, and she says, “You can take my car on tour!” I was like, “Sure!” She was going to Hawaii or something. I get the keys, take the car—she said I could do it!

We’re loading up the car the night before we leave, and she calls. I didn’t answer the phone. Obviously, the message was, “Don’t take the car, I had second thoughts.” So … little did she know we were going on a thousand-mile Dead tour.

I get up the next morning, get my boys, and we cruise to Houston, which was the next Dead show. So it’s the first night, and I’m sitting with my pals; we have photographs of all these shows spread out like cards with some sort of white substance spread around—you know? We’re young and stupid. Then we all go to the show. There’s five of us on the aisle. Not great seats, thirty or forty rows back. I had a friend who was in the middle of the row. I said, “Dude, would you mind? I’ll give you my aisle seat. I want to go to the middle because I’m taping.” He said, “No, that’s cool. That’d be great.” So he takes the aisle, and we all shoot down to the center.

The next day, half my crew goes to the next show, which was in Austin at Maynard Downs. We’re cruising into town, and we stop and get a chicken-fried steak the size of a floor mat. Then we’re driving into Austin, and we see this old off-white pickup truck with a camper on the back and it’s full of Deadheads. We’re laughing. “Holy shit, look at those crazy fucking Deadheads!” We pull up to a stoplight, and this dude runs out of the truck and he’s taking a piss. We’re right behind the truck, he’s still pissing, the light turns green, and everybody just takes off. The guy’s still pissing and we’re like, “Whatever!”

So we keep going, we get down two more stop signs. I look over, and it’s my friend who’d switched seats with us the night before at the show. We go, “GB?!” He is sitting in the passenger seat of this truck.

I go, “By the way, just wanted to let you know you lost a fella back there about three lights.”

He says, “Oh, whatever.”

I say, “What are you guys doing?”

He says, “We’re going to Hippy Hollow.”

And we say, “Alright!”

We don’t even know what Hippy Hollow is, but we follow him. We come to this big lake, it’s afternoon, we’re hanging out, we’re swimming. My friend Rusty always had his camera, and I told him to take a picture of this big naked guy swimming. Soon enough, this guy walks up to Rusty and says, “If you point that fucking camera at me one more time, I’m gonna take it and shove it up your ass.”

And we’re like, “Whoa!”

Rusty’s like, “Fine, got it.”

So the guy walks away and is stepping on some rocks in the water and Rusty keeps taking pictures of him the whole time. I’m like, “Rusty, what are you doing? You’re gonna get us all killed!” And the guy stops for a second, and Rusty puts the camera down. He walks away, and Rusty’s taking pictures of him the whole time. I’m like, “Are you out of your mind?” Anyhow, we’re swimming in this beautiful place in Austin all day. We get a hotel and invite GB to come spend the night with us. This is the beginning of me being a real Deadhead.

The next day we go to the show, Fourth of July, Maynard Downs. We’re all hanging in the parking lot, kicking hacky-sack and drinking beer and all that stuff, and we’re about to go in. I don’t remember how it happened, but I picked up GB’s tape deck and I dropped it and fucked it up. We didn’t find out until we’re finally inside the show that I fried his tape deck. It happens.

That Fourth of July in Maynard was an amazing show. It was really fantastic. Even though I broke GB’s tape deck, he ended up hopping into my borrowed car and we drove to Oklahoma City, St. Louis, and … I’m forgetting some city. Anyway, we end up hanging out together and meeting all of his crazy Deadhead friends. I was twenty-two or twenty-three, something like that.

We were just living in parking lots, and my friend’s brand-new car—she had the car for one month—was full of Dead stickers! The trunk was full of Dead stickers, solid. If you lifted up the hood, they were all on the inside and all on the bumper, too. I knew not to put it on the tank of the car. Needless to say, she was a little upset. That was a fun adventure. That was my very first real little Dead tour I’d ever been on. It was cool.

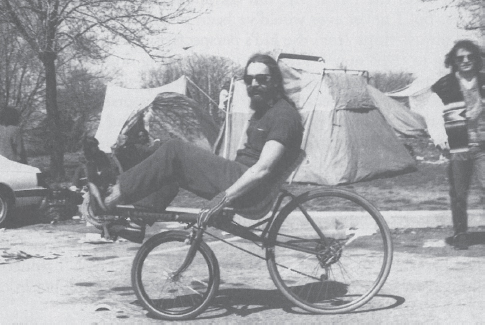

Let’s go for a ride, Philadelphia, 1986. Courtesy of Steve Eichner.

Fast forward several years …

Weir and I used to mountain bike a lot. Of course, we used to crash a lot, too! One summer, Weir went to Colorado, and he really got into mountain-bike riding. He came back and bought a brand-new red mountain bike. I had one already, so one day we were out teaching each other to ride. It’s hard, riding a mountain bike; it’s a lot different than riding on the street.

We’re riding, we get halfway up this huge hill on Mount Tamalpais, and he wants to switch bikes. So we switch bikes. Well, Weir’s smaller than me, so I’m riding, and it feels like my legs are having to go twice as fast because the seat on the bike is lower. He’s also in much better shape than me because he runs all the time. So he hauls ass up to the top of the mountain. He gets all the way up there and waves his hand. I get off his bike, and I walk up to the top, and he’s laughing because on the side of my bike it says, SPORT! He says, “Look at that! ‘Sport’! I love that!” I was wiped out, I was so tired. We hung out for a little while, and then we decided to go down.

We were brand-new at this, so we really didn’t know how dangerous we were being or how fast we were going. We made it down the fire trail, but then, we came onto pavement. We were zipping down, going really fast! I said, “Hey, we should slow down.” Within the next five seconds, there was a deep manhole cover in the middle of the road. Bobby hit it, and he went over the handlebars. He was on the ground, I slammed on my brakes, I fly off, me and my bicycle land on top of Bobby, and then we both flew further.

So, about fifteen feet and a lot of scratches later, he looked up at me and said, “Are you okay?” I said, “I’m okay. Are you okay?”

Bobby said, “I think so.”

I looked at his shoulder; it was totally separated and broken. I said, “I don’t know how okay you are right now …”

I ran down to his house, which wasn’t too far, got his girlfriend, got in the car, went back up, and Weir was walking the bikes down the hill. All the wheels were warbled, everything was messed up. I mean, I landed right on him! Later, I got the reputation as the guy who broke Weir’s collarbone! My stand on that was that Weir was, and still is, totally capable of breaking his own collarbone without any help from me!

Another time, the Dead did a tour during the Harmonic Convergence. We put the mountain bikes on one of the trucks. We rode all over that summer—in Colorado and Telluride and all that. I’d always go out riding with Bobby. That was fun.

I remember coming back from New Orleans in 1988, I think it was, and Weir was coming to spend the night at my parents’ house in Lafayette, Louisiana. It was his birthday, and we were having a party for him. My dad said, “No way. I’m going fishin’!” So my dad hit the road, and I invited a bunch of Deadheads to my house.

So before the party, we’re in my dad’s vane, and as we pulled into Breaux Bridge coming from New Orleans, Weir says, “Pull over!” I pull over, and Weir says, “Let me out, I’ll meet you at your house.”

I’m like, “Do you even know where you are? You’re in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana.”

He says, “I’ll find it. What’s the address?”

I’m like, “How are you even gonna find the house?” It was daytime, but still. He pulls his bike off the van and rides off.

Sure enough, I don’t know how he found it, but an hour and a half later, he shows up in the driveway. Most people you have to tell directions to and it’s like, “Write ’em down!” He must’ve stopped a couple times to ask for directions. It was incredible. Bobby rode from Breaux Bridge to Lafayette—nine miles—by himself. I was a little nervous because there was no way to find him. There were no cell phones or anything back in those days. Anyhow, he walked in like it was no big deal.

Will Sims

Waverly, Alabama

In 1995, I was handicapped by this massive leg break. I was going to a party, and I stopped by my parents’ house to do something and I noticed there was some water coming out of the bottom of my car. I opened up the radiator cap. This steam shot out, and I jumped back and my foot got caught under the bumper of the car and I broke my leg—a massive break in my lower leg. I woke up in the hospital, and the first thing I said when I opened my eyes was, “Am I gonna be able to see the Grateful Dead?” My mom tells that story all the time: “The first thing he said when he opened his eyes was, ‘What about the Dead shows?’”

So I’m in the hospital, and my buddies are getting all fired up about the shows at the Omni in Atlanta. I had to be in the hospital for a week, and I think the shows started the the day after I got out. I had tickets to a ton of shows that year; I was at an age where I could finally break away and do it.

I called the Omni and said, “Look, I just broke the shit out of my leg. If I come to the show, I’m gonna be messed up.” And they said, “No problem! We’ll just put you in the wheelchair section. You and a friend can come.” I had two or three tickets to the Atlanta shows, so I called up my buddy and said, “Look dude, I’ve got you a ticket to the Dead shows for the rest of the run.”

So I get this wheelchair from the hospital, an old-school wheelchair—heavy as shit! Iron. You put your feet down on these little paddles. I had a cast halfway up my thigh, and I had to move the paddle thing so my foot stuck straight out. I had this bungie cord attaching my leg to the chair so I could just roll through the crowd. I was a big hit! It was crazy.

The wheelchair section was the biggest party at the Grateful Dead shows from what I experienced. I didn’t know what to expect. We’re going the first night, I’m fresh out of the hospital, we get to the Omni Hotel in Atlanta, and a buddy of mine had some mushrooms. I’d never eaten mushrooms before in my life, but I go ahead and eat a couple caps. We roll through the hotel, and the mushrooms are kicking in. I want to say we passed Ted Turner from the CNN Center in the middle of the Omni, but I don’t if I hallucinated it or not. We were all just a bunch of stupid kids! I think we passed Ted Turner in the hall, and everybody freaked out.

We hung out all day in the parking lot scene. We were doing the whole deal and had a big ol’ time down there. I had a big cast, everybody knew my leg was broken, and they were really amazed, like, “Man, you’re really going all out to be here.” People were slapping Dead stickers on the back of my wheelchair. People we were giving me beers. Anyhow, we get in line to get into the show, and this guy just comes up and grabs me and says, “Come on, man. I’ll get you in here!” and he just blows through the line! “We got a wheelchair here!” Rolls me through. There’s a thirty-minute wait, and he just rolls me into the show. They rip our tickets, and we’re in. My buddies are still standing way back in the line.

I got grabbed left and right and jerked around in my wheelchair. People would use me to get through lines. Just random folks. They’d grab me and just start racing down the ramps like racing a grocery cart, standing on the back of the wheelchair. We had a fucking blast. I can just remember passing people, and they’re just hauling ass. I would steer with the brakes. With those old wheelchairs, you had the brakes on either side. We were wreaking havoc, having fun, not doing anything wrong, just having a good time racing.

I’ll just never forget—I reflect on this often—that first night when I was coming down in that wheelchair. It was really weird—probably because I was a person in a wheelchair—but everybody was smiling! I was smiling, and it was one of the most magical moments of my life. I had those butterflies you get for a show, and everybody else does too—it makes me want to cry now thinking about it. It was a magical time. It was thirty minutes before showtime, it was the first time I did psychedelics, and it was just an amazing, special moment.

You got to keep in mind that my foot’s sticking out two feet out, and my toes are sticking out of the cast, and I’m running into people left and right. Finally, we get into the wheelchair section. It was crazy in there—nobody fucks with the wheelchair section! You can do whatever you want in there. It was a full-on party. People were slinging shit from underneath their wheelchairs, running drugs and booze to their buddies. I was kind of in the crew, and things were flying!

Then I park next to this guy. He was the nicest guy I think I may have ever met in my life. He was paraplegic. A huge Dead fan, he was telling me all about his family and his life. We got to be buddies really fast. I sat next to him three or four nights in a row. I would help burn him down with a pipe. I wish I could remember his name. I think about him all the time. I see his face when I think about him, but I don’t remember his name. We hung out, and it was just such an amazing experience. Again, I was fresh on the scene, way more so than him. He told me that he wouldn’t be alive today if he weren’t a paraplegic. He was swimming and dove off a rock into a river and broke his neck. He said, “I’d be dead if I hadn’t done that. I’m here with you watching the Grateful Dead, and that’s better than the alternative.” It’s so hard to articulate the experience that it was. It was amazing. I mean it really was. He was a really special person. I’d love to reconnect with him if he’s still around just to see him again. He’d obviously seen the Dead forever, and he played a huge role in my experience at those shows. I just got a quick snapshot into the life of those guys. I mean, I’m not in a wheelchair now, but if it came down to it, I think I would have a much better outlook on it than a lot of people would because I’ve seen people happy and doing what they want to do. And I think that’s super special.

When the band got going, it was so awesome to look around and just to see all these people in wheelchairs. Some guys could move their arms and some guys couldn’t and everybody was smiling, loving life. That’s so fucking unusual. It was beautiful. It was fucking beautiful. I wouldn’t trade that for the third-row seat that I originally had that night, honestly. I probably would have that night going in—but looking back now, twenty years later, I wouldn’t. It was such a really special experience to have had. I saw it from their perspective, and it was a beautiful place. I was surrounded people who were physically fucked up. I mean, I think I was the only guy there with just a broken leg. And I was probably the only guy there that was nineteen. Everybody there was in their forties or fifties and had been on the Dead tour most of their lives. We were all dancing. We were high fivin’. I was patting my buddy on the back. We were having fun.

I saw a ton of shows in 1995 in that wheelchair—not just Grateful Dead shows. But the Grateful Dead shows were the only place I was treated with respect in a wheelchair. I had some nightmare experiences at other shows. I got cussed out. I got rolled over. At Dead shows, people got out of my way. It was unreal.

Susana Millman

Long-time Deadhead and GD photographer; aka Mrs. McNally

I was flying on the MGM Grand for a short tour with the Dead, and what I most remember about it was that the seats in the main area moved around, and they were kind of playing bumper cars, particularly Billy and Mickey. They were smashing into each, which you can imagine drummers doing!

Chuck Staley

Restaurant owner, Roswell, Georgia

I had a 1987 Ford Tempo that got towed into seven straight shows—literally towed in. It came to the point where people would cheer when we’d come in. Then I’d have to walk to a local gas station, find another tow truck to come pull it out of the lot, and have them work on it while I was watching the Dead play. I remember when I went to trade that car in for another one, the guy was like, “How much gas you got in it, and how much did you spend on those Dead stickers? That’s about what your car’s worth.” There were Dead stickers all over that car, political stuff. When I’d come home from tour, my parents were like, “Do you need to park that thing in front of our house?”

One of the worst car stories was when I broke down near the tollbooth on the New Jersey Turnpike. My Tempo would make this noise, and as soon as it made that noise, I knew I had about thirty seconds to get the car somewhere before it was going to shut off. Well, it made that noise right when I was in the tollbooth and, needless to say, in New Jersey people weren’t real sympathetic. It’s 5:30, we’re trying to get to Meadowlands for the Dead show, and people were honking, like, “You idiot!” I was right in the middle of the road trying to stop everyone on the New Jersey turnpike so I could push my car to the side.